A Focus Group Interview Study of the Experience of Stress amongst School-Aged Children in Sweden

Abstract

1. Introduction

Background

2. Purpose

3. Methods

3.1. Design

3.2. Sample

3.3. Measures

3.4. Analytic Strategy

3.5. Ethical Considerations

4. Results

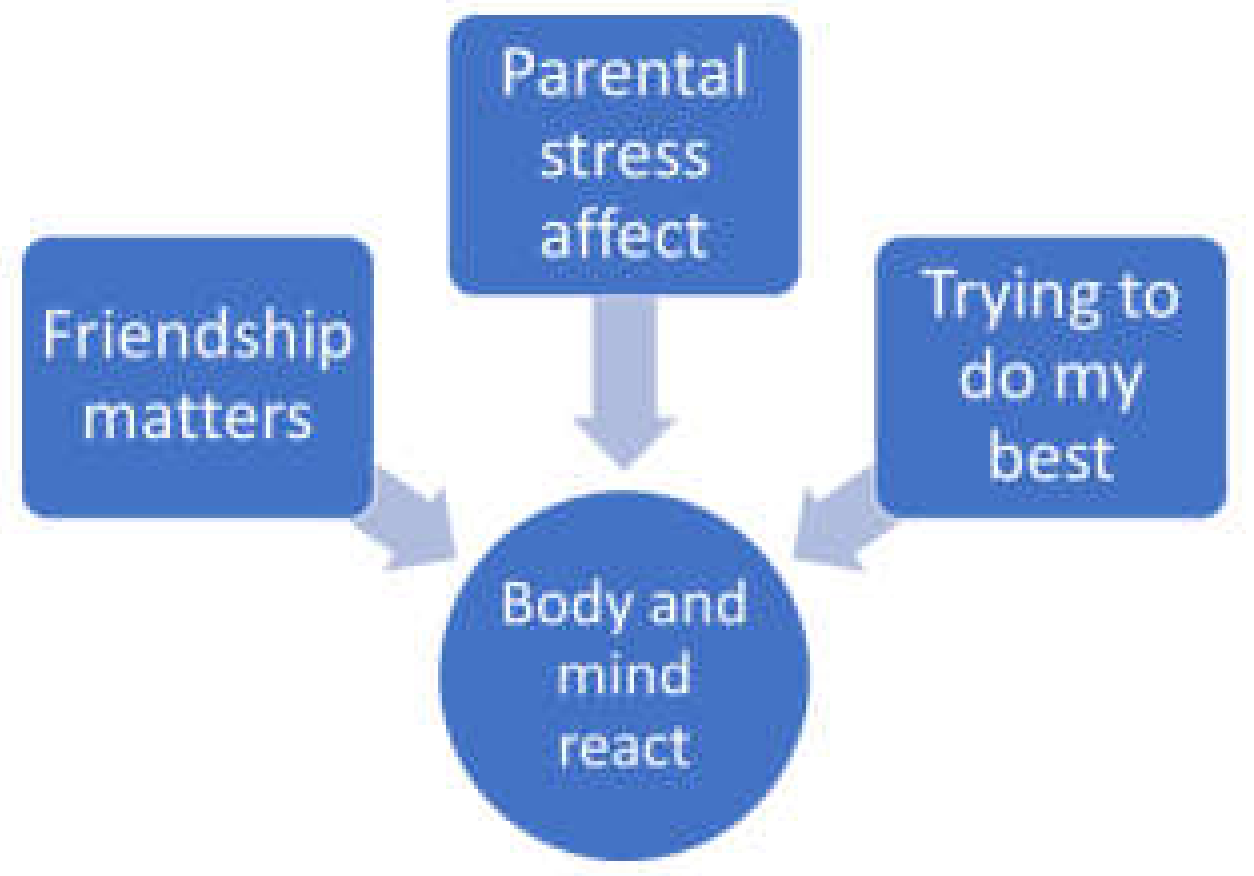

4.1. Theme: Body and Mind React

"Then when you are stressed it sometimes feels like you can break down for kind of anything" (Focus Group No. 10).

“The one who is stressed does not want to do much, just wants to be for herself. Gets irritated easily. I think you can notice a little that he or she is sad. That person is not so vibrant, he or she is more by herself. He or she does not want to talk about what he or she might be sad about” (Focus Group No. 2).

“If you are stressed, you are kind of very tired. You don’t want to talk to anyone. Just do what you must” (Focus Group No. 5).

4.1.1. Subtheme: Friendship Matters

“I get stressed if I’ve told a secret and then I realize that secret I probably shouldn’t have told” (Focus Group No. 6).

“When you fight because both get angry at each other and you are angry at each other then I get stressed. When the break is over and we haven’t straightened it out then I get stressed because I might be sitting next to her in class” (Focus Group No. 1).

“I get stressed when someone says, ‘You’re ugly’. Then I panic. I get angry and then you get depressed. I notice it when you don’t talk so loud and you become quiet” (Focus Group No. 3).

4.1.2. Subtheme: Parental Stress Affect

“When mom and dad are stressed and irritated, it feels like it’s my fault. I can get a bit annoyed and a bit sad because I think it is my own fault” (Focus Group No. 2).

4.1.3. Subtheme: Trying to Do My Best

“You have to pass all subjects and get good grades and if your parents get angry that you have bad grades, you are very stressed because you want good grades” (Focus Group No. 3).

“They say that it is not very important with grades yet, but it may feel a bit like it is very important” (Focus Group No. 8).

“You have a lot to do and a lot of things to do all the time and then you get stressed because you want to catch everything in time” (Focus Group No. 7).

“Sometimes it’s good to be stressed, but sometimes it’s pretty bad because sometimes stress puts a lot of pressure. And sometimes, well … for example, if I must go to school, then I hurry and then it goes faster if I stress. So, it can be good” (Focus Group No. 8).

5. Discussion

6. Strengths and Limitations

7. Implications for Practice

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ni, M.Y.; Jiang, C.; Cheng, K.K.; Zhang, W.; Gilman, S.E.; Lam, T.H.; Leung, G.M.; Schooling, C.M. Stress across the life course and depression in a rapidly developing population: The Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2015, 31, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Kubzansky, L.D.; Dunn, E.C.; Waldinger, R.; Vaillant, G.; Koenen, K.C. Childhood social environment, emotional reactivity to stress, and mood and anxiety disorders across the life course. Depress. Anxiety 2010, 27, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanaelst, B.; de Vriendt, T.; Huybrechts, I.; Rinaldi, S.; de Henauw, S. Epidemiological approaches to measure childhood stress. Paediatr. Périnat. Epidemiol. 2012, 26, 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joychan, S.; Kazi, R.; Patel, D.R. Psychosomatic pain in children and adolescents. J. Pain Manag. 2016, 9, 155. [Google Scholar]

- Selye, H. History of the stress concept. In Handbook of Stress: Theoretical and Clinical Aspects, 2nd ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Alfvén, G. Recurrent pain, stress, tender points and fibromyalgia in childhood: An exploratory descriptive clinical study. Acta Paediatr. 2011, 101, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rew, L. Adolescent Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Theory, Research, and Intervention; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hansson, E.; Garmy, P.; Vilhjálmsson, R.; Kristjánsdóttir, G. Bullying, health complaints, and self-rated health among school-aged children and adolescents. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, C.M.; Cipriani, F.M.; Meireles, J.F.F.; Morgado, F.F.D.R.; Ferreira, M.E.C. Body Image in Childhood: An Integrative Literature Review. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2017, 35, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohman, H.; Jonsson, U.; Päären, A.; Von Knorring, L.; Olsson, G.; Von Knorring, A.-L. Prognostic significance of functional somatic symptoms in adolescence: A 15-year community-based follow-up study of adolescents with depression compared with healthy peers. BMC Psychiatry 2012, 12, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevecke, K.; Resch, F. Stress und Coping. Prax. Kinderpsychol. Kinderpsychiatr. 2019, 68, 572–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelzig, O.; Sevecke, K. Coping with Stress during Childhood and Adolescence. Prax. Kinderpsychol. Kinderpsychiatr. 2019, 68, 592–605. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Sweden. Skolbarns Hälsovanor i Sverige 2017/2018 [Health Behaviour in Swedish School-Aged Children 2017/2018]; Public Health Agency of Sweden: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brobeck, E.; Marklund, B.; Haraldsson, K.; Berntsson, L. Stress in children: How fifth year pupils experience stress in everyday life. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2007, 21, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheetham-Blake, T.J.; Family, H.; Turner-Cobb, J.M. ‘Every day I worry about something’: A qualitative exploration of children’s experiences of stress and coping. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 931–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McQuarrie, E.F.; Krueger, R.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. J. Mark. Res. 1989, 26, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einberg, E.-L. To Promote Health in Children with Experience of Cancer Treatment. Ph.D. Thesis, Jönköping University, School of Health and Welfare, Jönköping, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Sweden. Statistical Database. 2018. Available online: http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/?rxid=9d7427ab-0101-4b77-b154-ba30ae4999e8 (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Brinkmann, S.; Kvale, S. Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim, U.; Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelley, M.; Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1984, 79, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, T.L.; Childless, J.F. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1991, 6, 129–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjern, A.; Alfvén, G.; Östberg, V. School stressors, psychological complaints and psychosomatic pain. Acta Paediatr. 2007, 97, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmy, P.; Hansson, E.; Vilhjálmsson, R.; Kristjánsdóttir, G. Bullying, pain and analgesic use in school-age children. Acta Paediatr. 2019, 108, 1896–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D.; Limber, S.P. Bullying in school: Evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2010, 80, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onnela, A.M.; Hurtig, T.; Ebeling, H.; Vuokila-Oikkonen, P. Mental health promotion in comprehensive schools. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 21, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmy, P.; Clausson, E.K.; Berg, A.; Carlsson, K.S.; Jakobsson, U. Evaluation of a school-based cognitive–behavioral depression prevention program. Scand. J. Public Health 2017, 47, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, C.; Cui, Z. Resilience-oriented cognitive behavioral interventions for depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 270, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well. Health Psychol. Read. 2012, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheidow, A.J.; Henry, D.B.; Tolan, P.; Strachan, M.K. The Role of Stress Exposure and Family Functioning in Internalizing Outcomes of Urban Families. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2013, 23, 1351–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragnarsson, S.; Myleus, A.; Hurtig, A.-K.; Sjöberg, G.; Rosvall, P.-Å.; Petersen, S. Recurrent Pain and Academic Achievement in School-Aged Children: A Systematic Review. J. Sch. Nurs. 2019, 36, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, J.-E. School, Learning and Mental Health: A Systematic Review; The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, The Health Committee: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Sanderson, K.; Venn, A.; Dwyer, T.; Gall, S. Association between childhood health, socioeconomic and school-related factors and effort-reward imbalance at work: A 25-year follow-up study. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 75, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golsäter, M.; Sidenvall, B.; Lingfors, H.; Enskär, K. Pupils’ perspectives on preventive health dialogues. Br. J. Sch. Nurs. 2010, 5, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, N.; Jamal, F.; Viner, R.M.; Dickson, K.; Patton, G.C.; Bonell, C. School-Based Interventions Going Beyond Health Education to Promote Adolescent Health: Systematic Review of Reviews. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 382–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vreeman, R.; Carroll, A.E. A Systematic Review of School-Based Interventions to Prevent Bullying. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2007, 161, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Thompson, D.E.; Gillen-O’Neel, C.; Gonzales, N.A.; Fuligni, A.J. Financial Strain, Major Family Life Events, and Parental Academic Involvement During Adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, L. Children’s health in Europe—Challenges for the next decades. Health Promot. Int. 2017, 33, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unicef. Convention on the Rights of the Child; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

| Focus Group (Number) | Sex, Number of Participants | School (Name) | Age (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 girls | A | 10 |

| 2 | 3 girls, 1 boy | A | 10–11 |

| 3 | 5 girls, 1 boy | A | 11–12 |

| 4 | 2 boys | A | 11–12 |

| 5 | 1 girl, 2 boys | A | 12 |

| 6 | 4 girls | A | 11–12 |

| 7 | 4 boys | B | 11–12 |

| 8 | 5 girls | B | 11–12 |

| 9 | 6 boys | B | 11–12 |

| 10 | 4 boys | B | 11–12 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Warghoff, A.; Persson, S.; Garmy, P.; Einberg, E.-L. A Focus Group Interview Study of the Experience of Stress amongst School-Aged Children in Sweden. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114021

Warghoff A, Persson S, Garmy P, Einberg E-L. A Focus Group Interview Study of the Experience of Stress amongst School-Aged Children in Sweden. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(11):4021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114021

Chicago/Turabian StyleWarghoff, Alexandra, Sara Persson, Pernilla Garmy, and Eva-Lena Einberg. 2020. "A Focus Group Interview Study of the Experience of Stress amongst School-Aged Children in Sweden" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 11: 4021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114021

APA StyleWarghoff, A., Persson, S., Garmy, P., & Einberg, E.-L. (2020). A Focus Group Interview Study of the Experience of Stress amongst School-Aged Children in Sweden. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 4021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114021