Research to Move Toward Evidence-Based Recommendations for Lead Service Line Disclosure Policies in Home Buying and Home Renting Scenarios

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Lead-Based Paint Disclosure Policy in the U.S.

1.2. Lead Service Line Disclosure Policy in the U.S.

1.3. Key Questions for LSL Disclosures in Home Buying/Renting Scenarios

1.4. Research Questions and Hypotheses

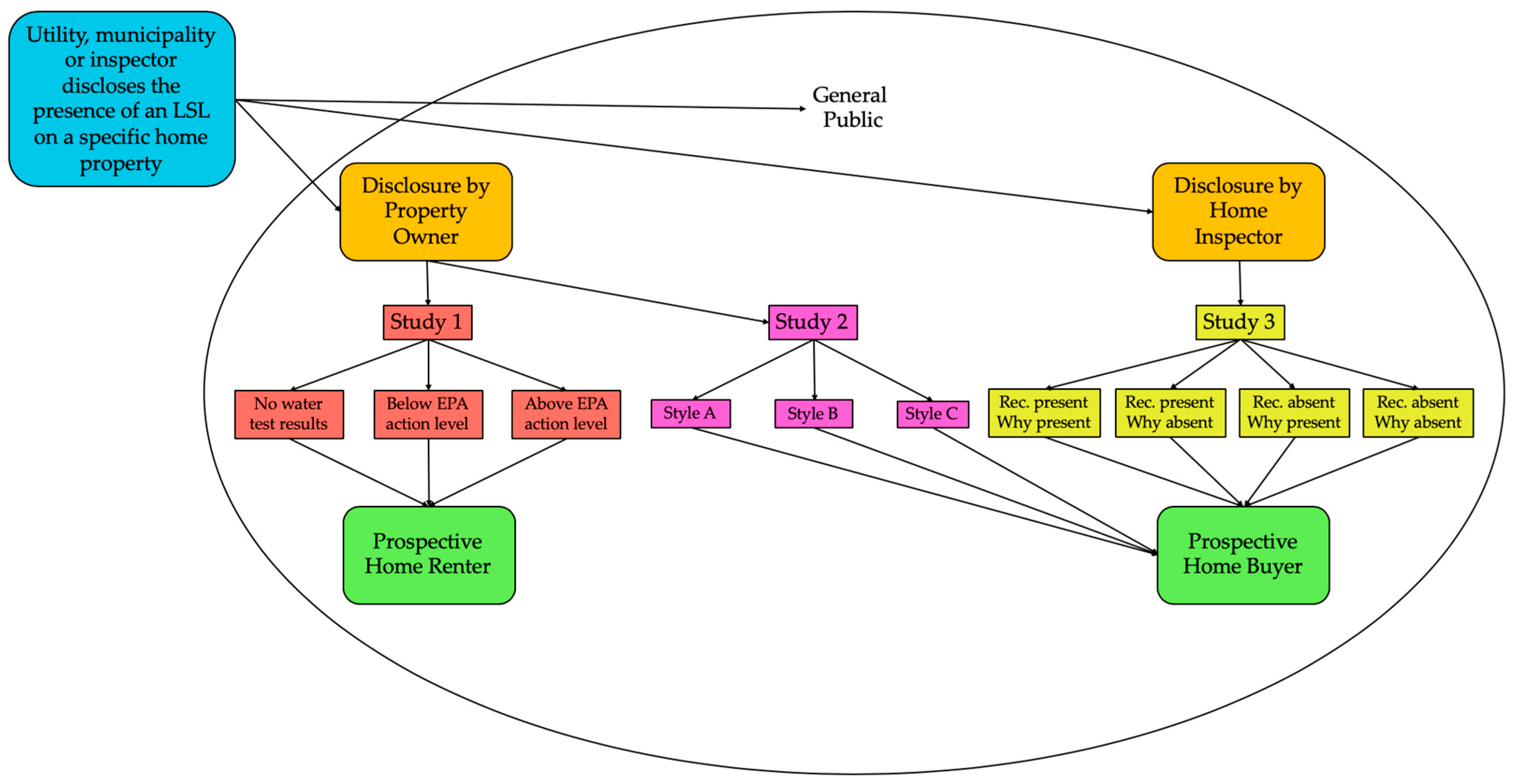

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure and Stimuli

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Willingness to Adopt Risk Mitigation Behaviors

2.3.2. Risk Perceptions

2.3.3. Response Efficacy

2.3.4. Self-Efficacy

2.3.5. Perceived Affordability

2.3.6. Click on the Link for Additional Information about Lead

2.4. Ethical Statement

3. Results

3.1. Overall Willingness to Engage in Each of the Renter or Buyer Behaviors

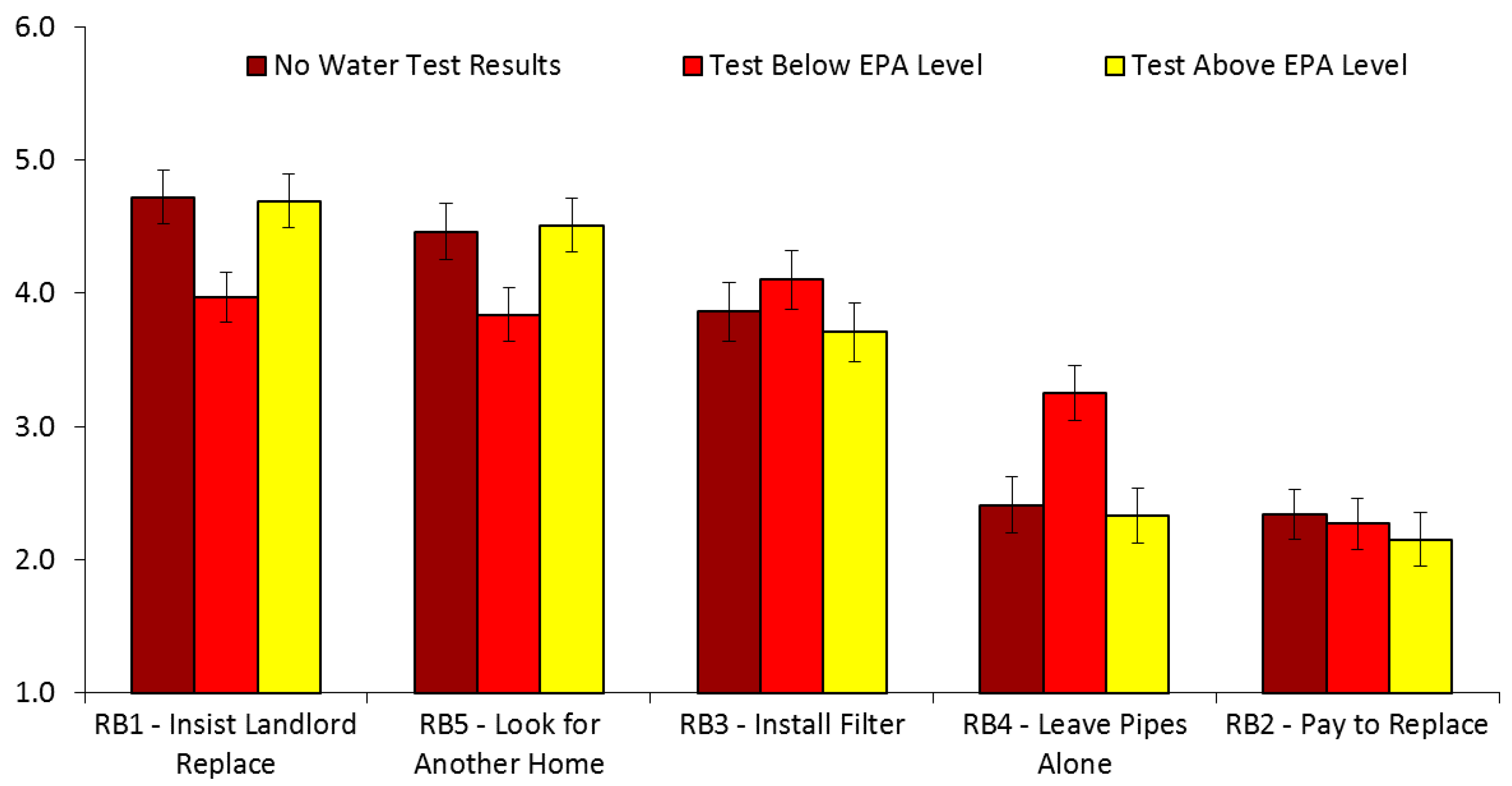

3.2. Study 1: Landlord Disclosures to Home Renters

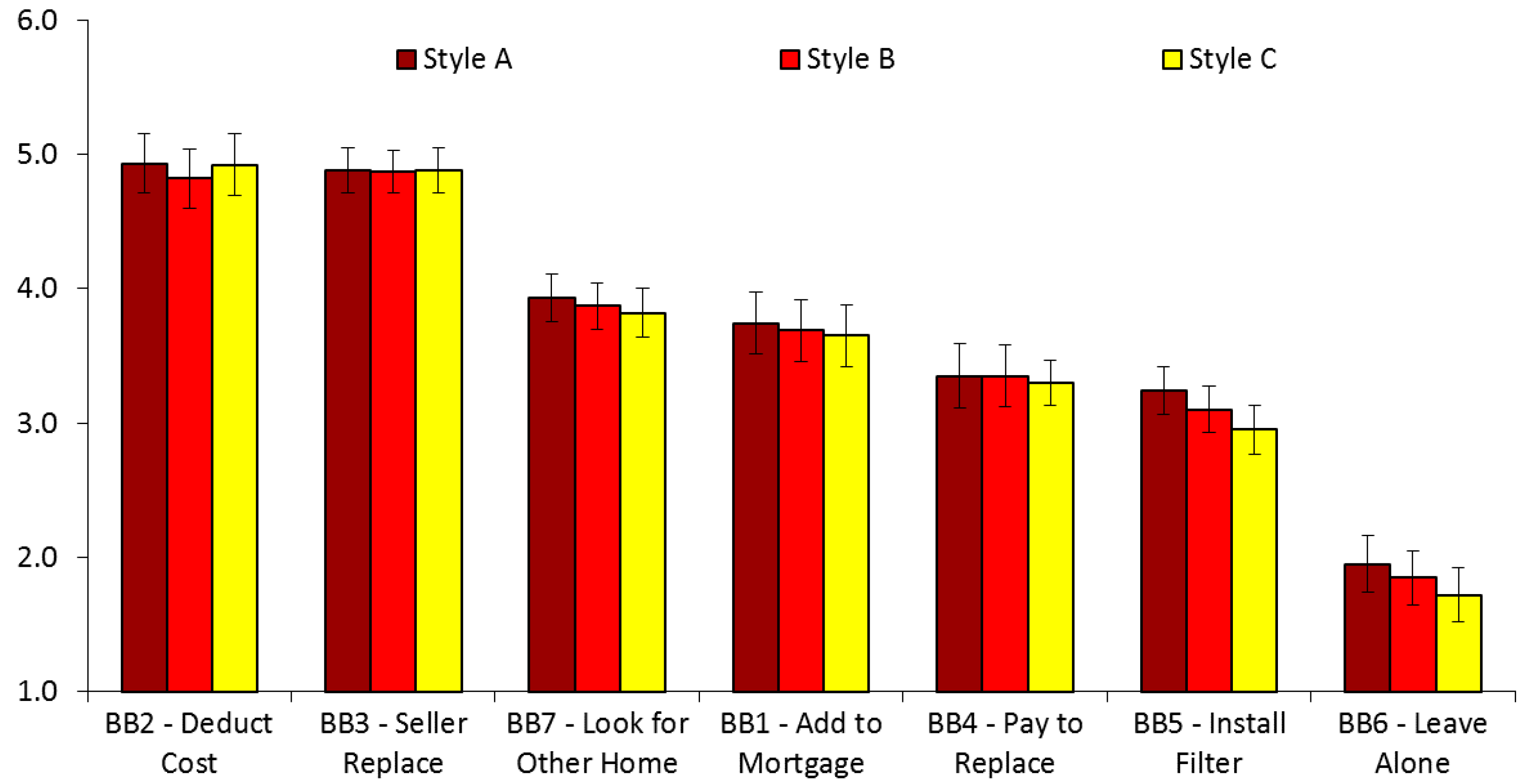

3.3. Study 2: Seller Disclosures to Home Buyers

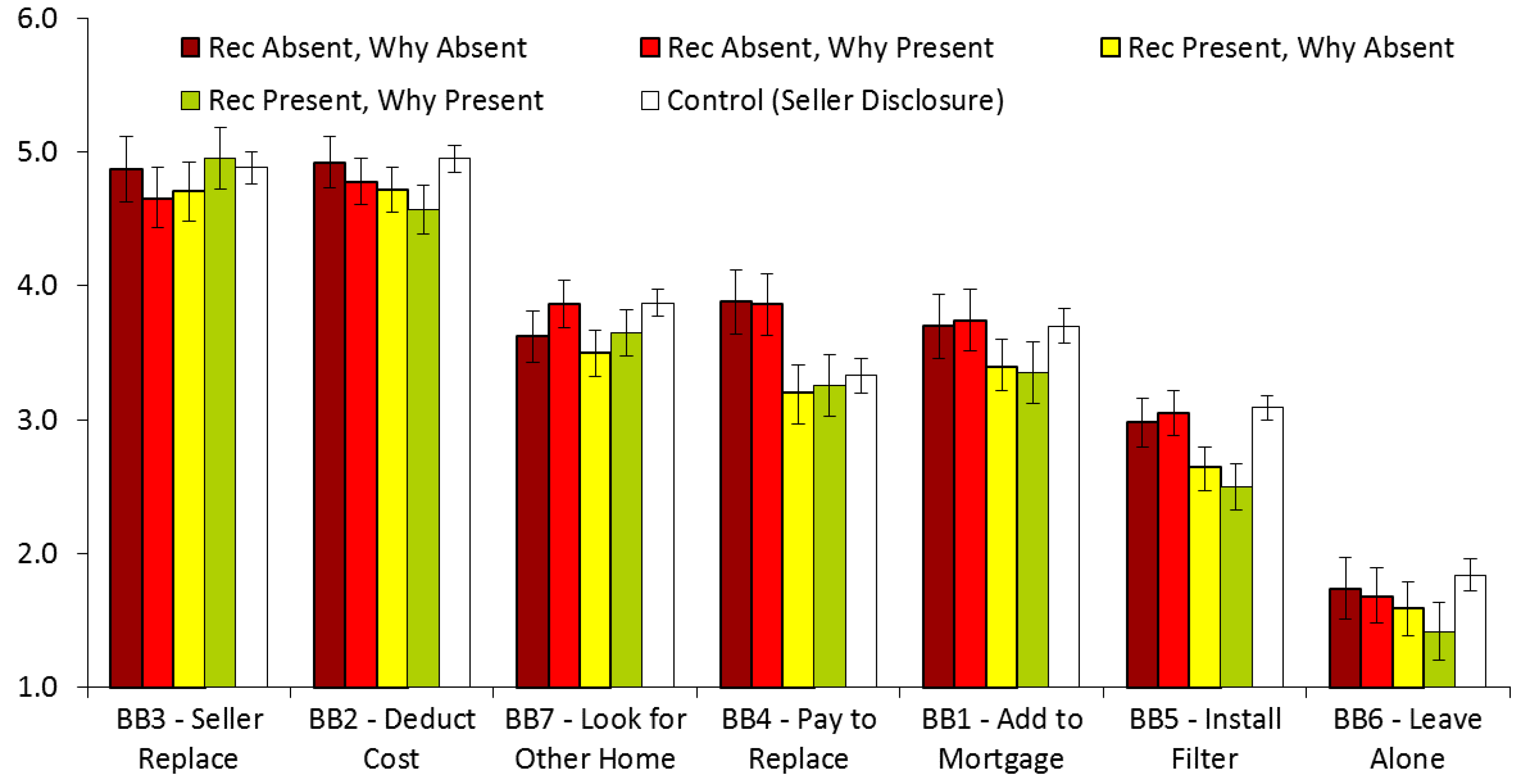

3.4. Study 3: Inspector Disclosures to Home Buyers

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings and Interpretation of Results

4.2. Study Limitations

4.3. Preliminary Recommendations for LSL Disclosure Policy and Practice

4.3.1. Requiring LSL Disclosure

4.3.2. Ensuring that Inspectors Look for LSLs

4.3.3. Dissociating Water Testing Results from LSL Disclosure

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Toxicology Program. NTP Monograph on Health Effects of Low-Level Lead [Internet]; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. Available online: https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/ohat/lead/final/monographhealtheffectslowlevellead_newissn_508.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2018).

- Environmental Protection Agency. Flint Drinking Water Response [Internet]; Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/flint (accessed on 3 September 2018).

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Drafting a new federal strategy to reduce childhood lead exposures and impacts: Request for information. Fed. Regist. 2017, 82, 49226–49228. [Google Scholar]

- Zartarian, V.; Xue, J.; Tornero-Velez, R.; Brown, J. Children’s lead exposure: A multimedia modeling analysis to guide public health decision-making. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 097009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandvig, A.; Kwan, P.; Kirmeyer, G.; Maynard, B.; Mast, D.; Trussell, R.R. Contribution of Service line and Plumbing Fixtures to Lead and Copper Compliance Issues [Internet]; Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. Available online: https://archive.epa.gov/region03/dclead/web/pdf/91229.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2018).

- Environmental Protection Agency. Real Estate Disclosure [Internet]; Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/lead/real-estate-disclosure (accessed on 3 September 2018).

- Cornwell, D.; Brown, R.; Via, S. National survey of lead service line occurrence. J Am Water Works Assoc. 2016, 108, E182–E191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- President’s Task Force on Environmental Health Risks and Safety Risks to Children. Eliminating Childhood Lead Poisoning: A Federal Strategy Targeting Lead Paint Hazards [Internet]; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/about/fedstrategy2000.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2018).

- Edwards, M. Fetal death and reduced birth rates associated with exposure to lead-contaminated drinking water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Environmental Protection Agency. Lead: Requirements for disclosure of known lead-based paint and/or lead-based paint hazards in housing. Fed Regist. 1996, 61, 9064–9088. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. American Healthy Homes Survey: Lead and Arsenic Findings [Internet]; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. Available online: https://www.hud.gov/sites/documents/AHHS_REPORT.PDF (accessed on 3 September 2018).

- National Safe and Healthy Housing Coalition. Find It, Fix It, Fund It: A Lead Elimination Drive, Policy Recommendations to Congress and the New Administration [Internet]; National Safe and Healthy Housing Coalition: Columbia, MD, USA, 2016; Available online: http://leadconversation.net/wp-content/uploads/FFF-Action-Drive-Transition-Document_Admin-Version_2017-02-07.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2018).

- Bellinger, D.C. Childhood lead exposure and adult outcomes. JAMA 2017, 317, 1219–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Environmental Defense Fund. Grading the Nation: State Disclosure Policies for Lead Pipes [Internet]; Environmental Defense Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.edf.org/sites/default/files/content/edf_lsl_state_disclosure_report_final-031317.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2018).

- Environmental Defense Fund. Community and Utility Efforts to Replace Lead Service Lines [Internet]; Environmental Defense Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.edf.org/health/recognizing-community-efforts-replace-lsl (accessed on 13 February 2019).

- National Drinking Water Advisory Council. Recommendations to the Administrator for the Long-Term Revisions to the Lead and Copper Rule [Internet]; National Drinking Water Advisory Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-01/documents/ndwacrecommtoadmin121515.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2018).

- National Drinking Water Advisory Council. Report of the Lead and Copper Rule Working Group to the National Drinking Water Advisory Council [Internet]; National Drinking Water Advisory Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-01/documents/ndwaclcrwgfinalreportaug2015.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2018).

- Environmental Protection Agency. EPA Letter to Governors and State Environment and Public Health Commissioners [Internet]; Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/dwreginfo/epa-letter-governors-and-state-environment-and-public-health-commissioners (accessed on 25 September 2018).

- Environmental Protection Agency. 3Ts for Reducing Lead in Drinking Water in Schools and Child Care Facilities: A Training, Testing, and Taking Action Approach [Internet]; Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2018-09/documents/final_revised_3ts_manual_508.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2018).

- Haenen, M.A.; de Jong, P.J.; Schmidt, A.J.; Stevens, S.; Visser, L. Hypochondriacs’ estimation of negative outcomes: Domain-specificity and responsiveness to reassuring and alarming information. Behav. Res. Ther. 2000, 38, 819–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, D.; Druckman, J.N. Framing theory. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2007, 10, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannenbaum, M.B.; Hepler, J.; Zimmerman, R.S.; Saul, L.; Jacobs, S.; Wilson, K.; Albarracín, D. Appealing to fear: A meta-analysis of fear appeal effectiveness and theories. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 1178–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Environmental Protection Agency; United States Consumer Product Safety Commission; United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. Protect Your Family from Lead in Your Home [Internet]; Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. Available online: https://www.cpsc.gov/Global/Safety%20Education/Furniture%20Furnishings%20Decorations/426ProtectYourFamilyFromLeadinYourHome.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2018).

- Dillard, J.P.; Li, R.; Meczkowski, E.; Yang, C.; Shen, L. Fear responses to threat appeals: Functional form, methodological considerations, and correspondence between static and dynamic data. Commun. Res. 2017, 44, 997–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basil, D.Z.; Ridgway, N.M.; Basil, M.D. Guilt and giving: A process model of empathy and efficacy. Psychol. Market. 2008, 25, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Statistical Methods for Communication Science; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Home Inspectors. The Standard of Practice for Home Inspections and the Code of Ethics for the Home Inspection Profession [Internet]; American Society of Home Inspectors: Des Plaines, IL, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.homeinspector.org/files/docs/standards_updated3-4-2015.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2018).

- Iyengar, S.S.; Lepper, M.R. When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 995–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brehm, J.W. A Theory of Psychological Reactance; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger, D.C. Lead contamination in Flint—An abject failure to protect public health. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 1101–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, M.; Zhang, D.; Morgan, J.C.; Ross, J.C.; Osman, A.; Boynton, M.H. Similarities and differences in tobacco control research findings from convenience and probability samples. Ann. Behav. Med. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographics | Landlord/Renter | Seller/Buyer | Inspector/Buyer |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 667 | N = 667 | N = 871 | |

| Age (mean) | 33.3 | 42.1 | 42.0 |

| Gender (%) | |||

| Male | 47.1 | 42.1 | 40.3 |

| Female | 51.3 | 57.1 | 59.4 |

| Transgender or other category | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| Education (%) | |||

| Some high school or less | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| High school diploma/equivalent | 10.0 | 7.9 | 8.2 |

| Some college, no degree | 25.5 | 17.1 | 18.4 |

| Associate degree | 12.3 | 12.0 | 14.5 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 37.5 | 42.9 | 40.6 |

| Master’s degree | 10.8 | 15.7 | 14.2 |

| Professional degree (MD, JD) | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.3 |

| Doctorate degree | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.3 |

| Race (%) | |||

| White | 80.4 | 86.4 | 85.4 |

| Black or African American | 11.4 | 7.3 | 7.6 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 2.5 | 1.8 | 2.0 |

| Asian/Indian | 2.1 | 1.3 | 2.1 |

| Chinese, Japanese or Korean | 3.8 | 1.8 | 3.1 |

| Filipino or Vietnamese | 2.1 | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| Pacific Islander/Hawaii Native | 0.1 | 0 | 0.4 |

| Other Asian | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Other race | 2.8 | 1.8 | 1.4 |

| Hispanic/Latino (%) | 11.5 | 7.5 | 8.4 |

| Marital status (%) | |||

| Married | 29.1 | 56.1 | 59.5 |

| Widowed | 0.9 | 2.4 | 1.6 |

| Divorced | 4.8 | 10.8 | 10.1 |

| Separated | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| Never married | 42.7 | 18.0 | 16.2 |

| Living with a partner | 21.1 | 11.1 | 11.3 |

| Household income (%) | |||

| $24,999 or less | 21.9 | 9.4 | 8.5 |

| $25,000 to $34,999 | 19.2 | 10.2 | 8.7 |

| $35,000 to $49,999 | 20.4 | 16.8 | 13.9 |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 23.7 | 24.7 | 24.9 |

| $75,000 to $99,999 | 9.3 | 18.1 | 22.3 |

| $100,000 to $149,999 | 3.6 | 12.9 | 15.7 |

| $150,000 or more | 1.9 | 7.8 | 6.0 |

| Own home (%) | 8.2 | 73.3 | 75.2 |

| Have children (%) | 30.7 | 60.7 | 61.4 |

| Living with children under 12 (%) | 25.9 | 34.6 | 37.4 |

| Have pets (%) | 58.0 | 68.8 | 71.2 |

| Political party (%) | |||

| Republican | 13.3 | 28.5 | 26.4 |

| Democrat | 46.3 | 39.1 | 37.8 |

| Independent | 32.1 | 26.5 | 29.5 |

| Another party | 2.5 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| No preference | 5.7 | 4.5 | 5.2 |

| Political ideology (%) | |||

| Liberal | 60.3 | 48.7 | 45.9 |

| Moderate | 18.7 | 18.4 | 20.6 |

| Conservative | 20.9 | 33.8 | 33.6 |

| Heard of LSLs before (%) | 18.6 | 29.8 | 29.9 |

| Specific Renter Behavior (RB) or Buyer Behavior (BB) | Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 667 | N = 667 | N = 871 | |

| M (SE) | M (SE) | M (SE) | |

| BB1: I would add the cost of replacement ($1000–$5000) to the mortgage and replace the lead pipes after purchasing the home, but before moving in. | N/A | 3.70 (0.07) a,b,c,d,e | 3.54 (0.06) a,b,c,d |

| BB2: I would deduct the estimated cost ($1000–$5000) of replacing the lead pipes from the sale price and use those funds to replace the pipes before moving in. | N/A | 4.89 (0.05) a,f,g,h,i | 4.74 (0.05) a,e,f,g,h |

| RB1/BB3: I would insist that the (landlord/seller) replace the lead pipes with non-lead pipes (as a condition of renting/prior to closing on the home). | 4.46 (0.06) a,b,c,d | 4.88 (0.05) b,j,k,l,m | 4.79 (0.05) b,i,j,k,l |

| RB2/BB4: I would pay to replace the lead pipes ($1000–$5000) after moving in. | 2.25 (0.06) a,e,f,g | 3.33 (0.07) c,f,j,n,o | 3.53 (0.06) e,i,m,n |

| RB3/BB5: I would move in, and install and maintain a filter designed to remove lead even though I must replace the filter monthly at a cost of about $150 a year. | 3.89 (0.07) b,e,h,i | 3.09 (0.07) d,g,k,p,q | 2.79 (0.06) c,f,j,m,o,p |

| RB4/BB6: I would move in and leave the lead pipes alone. | 2.67 (0.06) c,f,h,j | 1.84 (0.05) e,h,l,n,p,r | 1.61 (0.04) d,g,k,n,o,q |

| RB5/BB7: I would look for another home to (rent/buy). | 4.27 (0.06) d,g,i,j | 3.87 (0.06) i,m,o,q,r | 3.65 (0.06) h,l,p,q |

| Outcome Variables | No Water Test Results | Below EPA Action Level | Above EPA Action Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 226 | N = 225 | N = 216 | |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| RB1: I would insist that the landlord replace the lead pipes as a condition of renting. | 4.72 (1.35) a | 3.97 (1.70) a,b | 4.69 (1.38) b |

| RB5: I would look for another home to rent. | 4.46 (1.33) a | 3.84 (1.56) a,b | 4.51 (1.49) b |

| RB3: I would move in, and install and maintain a filter that is designed to remove lead, even though I must replace the filter monthly at a cost of about $150 a year. | 3.86 (1.67) | 4.10 (1.62) a | 3.71 (1.76) a |

| RB4: I would move in and leave the lead pipes alone. | 2.41 (1.51) a | 3.25 (1.72) a,b | 2.33 (1.54) b |

| RB2: I would pay to replace the lead pipes ($1000–$5000) after moving in. | 2.34 (1.57) | 2.27 (1.48) | 2.15 (1.43) |

| Risk perceptions | 5.09 (0.74) a | 4.92 (0.70) a,b | 5.11 (0.75) b |

| Response efficacy | 5.15 (0.88) | 5.16 (0.96) | 5.16 (0.94) |

| Self-efficacy | 3.25 (1.35) | 3.13 (1.34) | 3.15 (1.39) |

| Affordability | 2.69 (1.30) | 2.69 (1.30) | 2.68 (1.32) |

| Click on the pamphlet link (%) | 17% | 20% a | 12% a |

| Outcome Variables | Style A | Style B | Style C |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 214 | N = 230 | N = 223 | |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| BB2: I would deduct the estimated cost ($1000–$5000) of replacing the lead pipes from the sale price, and use those funds to replace the pipes before moving in. | 4.93 (1.21) | 4.82 (1.32) | 4.92 (1.27) |

| BB3: I would insist that the seller replace the lead pipes with non-lead pipes prior to closing on the home. | 4.88 (1.30) | 4.87 (1.37) | 4.88 (1.24) |

| BB7: I would look for another home to buy. | 3.93 (1.58) | 3.87 (1.58) | 3.82 (1.50) |

| BB1: I would add the cost of replacement ($1000–$5000) to the mortgage, and replace the lead pipes after purchasing the home but before moving in. | 3.74 (1.69) | 3.69 (1.66) | 3.65 (1.72) |

| BB4: I would pay to replace the lead pipes ($1000–$5000) after moving in. | 3.35 (1.75) | 3.35 (1.77) | 3.30 (1.80) |

| BB5: I would move in, and install and maintain a filter designed to remove lead, even though I must replace the filter monthly at a cost of about $150 a year. | 3.24 (1.75) | 3.10 (1.74) | 2.95 (1.71) |

| BB6: I would move in and leave the lead pipes alone. | 1.95 (1.41) | 1.85 (1.33) | 1.72 (1.22) |

| Risk perceptions | 5.09 (0.82) | 5.11 (0.81) | 5.06 (0.75) |

| Response efficacy | 5.28 (0.89) | 5.26 (0.92) | 5.18 (0.93) |

| Self-efficacy | 4.59 (1.19) | 4.58 (1.08) | 4.67 (1.11) |

| Affordability | 4.45 (1.18) | 4.39 (1.17) | 4.33 (1.25) |

| Click on the link (%) | 15% | 14% | 15% |

| Outcome Variables | Rec. Absent Why Absent | Rec. Absent Why Present | Rec. Present Why Absent | Rec. Present Why Present | Seller Disclosure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 195 | N = 214 | N = 251 | N = 211 | N = 667 | |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| BB2: Deduct from sale price | 4.92 (1.28) | 4.77 (1.33) | 4.72 (1.29) | 4.57 (1.45) a | 4.89 (1.27) a |

| BB3: Insist seller replace | 4.87 (1.29) | 4.65 (1.36) | 4.71 (1.41) | 4.95 (1.35) | 4.88 (1.30) |

| BB4: Pay to replace | 3.88 (1.65) a,b,c | 3.86 (1.68) d,e,f | 3.20 (1.59) a,d | 3.26 (1.71) b,e | 3.33 (1.77) c,f |

| BB1: Add cost to mortgage | 3.70 (1.71) | 3.74 (1.69) | 3.39 (1.66) | 3.35 (1.74) | 3.70 (1.69) |

| BB7: Look for other home | 3.62 (1.68) | 3.86 (1.65) | 3.50 (1.64) a | 3.65 (1.56) | 3.87 (1.55) a |

| BB5: Install filter | 2.98 (1.69) a | 3.05 (1.70) b | 2.65 (1.70) c | 2.50 (1.61) a,b,d | 3.09 (1.74) c,d |

| BB6: Leave pipes alone | 1.74 (1.35) | 1.68 (1.25) | 1.59 (1.14) | 1.42 (1.01) a | 1.84 (1.32) a |

| Risk perceptions | 5.15 (0.86) | 5.21 (0.82) | 5.08 (0.82) | 5.32 (0.72) | 5.09 (0.79) |

| Response efficacy | 5.37 (0.82) | 5.33 (0.91) | 5.35 (0.90) | 5.49 (0.80) | 5.24 (0.91) |

| Self-efficacy | 4.68 (1.27) | 4.77 (1.14) | 4.70 (1.14) | 4.71 (1.22) | 4.61 (1.12) |

| Affordability | 4.56 (1.16) | 4.57 (1.05) | 4.42 (1.13) | 4.46 (1.18) | 4.39 (1.20) |

| Click on the link (%) | 17% | 17% | 15% | 13% | 15% |

|

|

|

|

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, H.; Romero-Canyas, R.; Hiltner, S.; Neltner, T.; McCormick, L.; Niederdeppe, J. Research to Move Toward Evidence-Based Recommendations for Lead Service Line Disclosure Policies in Home Buying and Home Renting Scenarios. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060963

Lu H, Romero-Canyas R, Hiltner S, Neltner T, McCormick L, Niederdeppe J. Research to Move Toward Evidence-Based Recommendations for Lead Service Line Disclosure Policies in Home Buying and Home Renting Scenarios. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(6):963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060963

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Hang, Rainer Romero-Canyas, Sofia Hiltner, Tom Neltner, Lindsay McCormick, and Jeff Niederdeppe. 2019. "Research to Move Toward Evidence-Based Recommendations for Lead Service Line Disclosure Policies in Home Buying and Home Renting Scenarios" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 6: 963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060963

APA StyleLu, H., Romero-Canyas, R., Hiltner, S., Neltner, T., McCormick, L., & Niederdeppe, J. (2019). Research to Move Toward Evidence-Based Recommendations for Lead Service Line Disclosure Policies in Home Buying and Home Renting Scenarios. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(6), 963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060963