Abstract

The number of Australians seeking food aid has increased in recent years; however, the current variability in the measurement of food insecurity means that the prevalence and severity of food insecurity in Australia is likely underreported. This is compounded by infrequent national health surveys that measure food insecurity, resulting in outdated population-level food insecurity data. This review sought to investigate the breadth of food insecurity research conducted in Australia to evaluate how this construct is being measured. A systematic review was conducted to collate the available Australian research. Fifty-seven publications were reviewed. Twenty-two used a single-item measure to examine food security status; 11 used the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM); two used the Radimer/Cornell instrument; one used the Household Food and Nutrition Security Survey (HFNSS); while the remainder used a less rigorous or unidentified method. A wide range in prevalence and severity of food insecurity in the community was reported; food insecurity ranged from 2% to 90%, depending on the measurement tool and population under investigation. Based on the findings of this review, the authors suggest that there needs to be greater consistency in measuring food insecurity, and that work is needed to create a measure of food insecurity tailored for the Australian context. Such a tool will allow researchers to gain a clear understanding of the prevalence of food insecurity in Australia to create better policy and practice responses.

1. Introduction

In Australia, like other developed nations, some populations are more vulnerable to, and experience greater, food insecurity [1,2]. Food security refers to a situation when “all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” [3]. This definition encompasses four hierarchical dimensions which are integral to achieve food security [4]. “Availability” refers to a reliable and consistent source of enough quality food for an active and healthy life. This might include home food production, transportation, and exchange systems for food. This dimension is also concerned that food is available in socially acceptable ways. “Access” is achieved when the resources required to acquire food are met and can include economic or physical resources. “Utilization” refers to the intake of sufficient and safe food and the physical, social and human resources to transform food into meals. The final dimension, “Stability”, recognizes that food insecurity can be transitory, cyclical or chronic [4]. All these dimensions are necessary for food insecurity to be understood as a continuum that progresses from uncertainty and anxiety about access to sufficient and appropriate food at the household level, to the extreme condition of hunger among children because they do not have enough to eat [5]. Food insecurity is caused by a range of circumstances, including low or unstable employment, poor food supply, illness, and financial pressures; people often fall prey to food deprivation not so much because food is unavailable on the market, but because their access to food is constrained [6].

Household food insecurity and nutritional vulnerability have significant health implications for both adults and children, with food insecurity having the potential to exacerbate existing health inequalities [7]. Food insecure households have been shown to consume low cost, poor quality foods, high in energy, fat, and sugar, and low in nutritional value [8]. Among adults, food insecurity is associated with an increased risk of chronic conditions including diabetes and hypertension [9], and anxiety, depression, and mood disorders [10]. Among children, food insecurity is associated with poor general health [11], atypical or problematic behaviour, and delayed development [12]. Severe food insecurity can also lead to nutritional deficiencies [13], and weight loss or weight gain [14]. Food insecurity may be transient, in that people move in and out of food insecurity as their circumstances change, though increasingly people are experiencing chronic food insecurity [15,16], and as a result, are turning in greater numbers to charities that provide food relief [17,18,19]. Given the very serious potential implications of food insecurity, understanding the ways in which researchers investigate food insecurity, and the findings of such research, is important for the creation of policy and practice responses.

Food security research in Australia is relatively new, with much of the research conducted in the past decade. The infancy of this work, and the variety of approaches taken to measure food security in general [20], means that researchers in Australia, like those investigating food insecurity internationally, have adopted a number of approaches to the measurement of food insecurity. Globally, many researchers rely on the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM) when measuring household food insecurity. The HFSSM consists of a set of questions based on the overall experience of household food insecurity, administered through a survey; results can be reported as a continuous score of severity, or with cut-off points through which households are classified into four categories [21]. The HFSSM is a household-level self-report of uncertain, insufficient or inadequate food access, availability, and utilization that can assesses the food security situation of adults and children within a household, but not the food security status of individuals in the household. The HFSSM contains 18 questions about the food security situation in the household over the previous 12 months. The measure can also be shortened to a 10-item and 6-item sub-scale that allow for the differentiation between low levels of food security and very low levels of food security. One limitation of this scale is that it does not capture reasons beyond financial constraints, poor resources, and compromised eating patterns and consumption. Webb et al. [6] suggest that the HFSSM is a valid way to measure household food insecurity in the USA, and with some modification the HFSSM has been used more widely in the Americas [22,23,24]. Other household food security scales, which use context-specific questions that differ from the HFSSM, have been used in developing countries based on in-depth assessments and understanding of the local experiences with food insecurity [25,26]. For example, in rural Bangladesh, themes within the scale included meals, cooking, and specific ingredients used in cooking and food management strategies [25], while in Burkina Faso, themes included agricultural production and decisions about production and uses of food, cooking and eating patterns, perception of food quality, coping and strategies [26].

Based on the HFSSM is the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES), created by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) [27,28]. The FIES consists of eight questions and measures the access dimension of food security, particularly financial aspects, but also the availability of quality food. Unlike the HFSSM, the FIES can measure individual food insecurity. The result of the FIES is a score of food insecurity severity. This instrument is relatively new; however, it has been used to assess food insecurity in a number of different countries [29,30,31].

An alternative to the HFSSM is the single-item measure often incorporated into population level health surveys. The single item askes: “In the last 12 months was there any time you have run out of food and not been able to purchase more?” This question has been included in the Australian National Health Survey (NHS), conducted every three years as an indicator for the severity of food insecurity. The most recent national level food security data collected by the Federal Government identifies the prevalence of food insecurity in the general Australian population to be approximately 5% [32]. This figure is said to be around 3% in Victoria, New South Wales (NSW), and South Australia, closer to 5% in Queensland, Western Australia, and the Northern Territory, and around 6% in Tasmania [33]. Researchers have investigated the validity of this question in determining food insecurity and have found that most likely results in under reporting food insecurity [7,34,35]. This single item originates from the Radimer/Cornell Food Security Scale (a measure of food insecurity) [36]. The Radimer/Cornell Food Security Scale was developed in the 1990s through in-depth interviews with women with children living at home who had experienced hunger [37]. These interviews resulted in two conceptualizations of hunger that were then used to create a food security scale: one that referred to insufficient food intake and going without food and the second that encompassed problems with household food supply, quality of diets, feelings about the situation, and coping.

Given the large amount of literature and research that has investigated food security over the past four decades, it is perhaps unsurprising that there also exists a number of systematic reviews on the topic. For example, there are systematic reviews that investigate the relationship between food insecurity and mental health [38], the role of food banks in alleviating food insecurity [17], and the experiences of students and food insecurity [39]. More closely related to this research are two recent reviews that have investigated measurement tools. The first is that of Ashby et al. [20], who investigated the use of multi-item tools in measuring food insecurity and explored which of the four dimensions of food security these tools measure. This research identified eight tools, each of which assessed the “access” dimension of food security, with two partially assessing the “food utilization” and “stability over time” dimensions. This study concludes with the suggestion that a tool should be created that measures all four dimensions of food insecurity. The second is that of Marques et al. [40] who sought to identify and characterize experience-based household food security scales. This research found that while there are a number of instruments available, most have been developed in the USA, and have undergone limited testing for reliability and validity.

This current systematic review is interested specifically in the food security research in Australia. While having many similarities with the USA, the food landscape and response to food insecurity from both government and non-government actors differs in Australia. While the HFSSM and the single item are the most common methods of identifying and classifying food insecurity, researchers and those in the food aid sector also employ other methods such as using measures of food consumed or food knowledge as a proxy for food security or attendance at a food bank as an indicator for food insecurity [19,41]. This lack of coherency concerning how food insecurity is measured likely has an impact on the reported prevalence, which likely influences policy and practice responses. This review seeks to (1) systematically investigate the peer reviewed literature that purports to investigate food insecurity in Australia, (2) identify the breadth of research being conducted in Australia, including the instruments used and the populations under study, and (3) provide an overview of the severity of food insecurity in Australia as presented by these studies.

2. Methods

A systematic search was undertaken to identify all food security research conducted in Australia. Key search terms were “food insecurity” OR “food security” OR “food availability” OR “food utilisation” OR “food access” AND “Australia”. Searched databases included EBSCOhost (including Academic Search Complete, CINAHL Complete, Global Health, and MEDLINE), and SCOPUS. In order to gain a full collection of articles that reported on food security research in Australia, no limits were placed on publication dates. Only peer reviewed articles published in English were considered; unpublished articles, books, theses, dissertations, and non-peer reviewed articles were excluded.

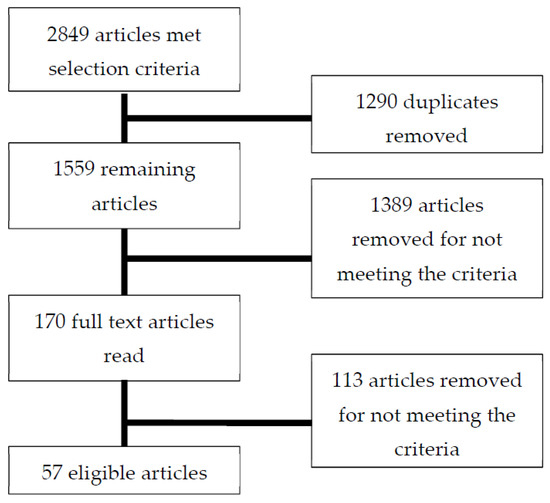

Two authors (FHM and BCH) reviewed all articles to identify relevant studies. Articles underwent a three-step process (see Figure 1). All articles were downloaded into EndNote X7, duplicates were identified and removed. Articles were first screened by title and abstract based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria above. Any article that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria was removed at this stage, any that did, or possibly could meet the inclusion criteria on further inspection, were retained. Full text of the remaining articles were obtained for further assessment. Two authors (FHM and BCH) independently read all 170 articles that remained at this stage and decided whether each article had met the inclusion criteria. Any articles at this stage that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria were removed. Of those that were retained, disagreements were discussed and settled by consensus. The reference lists of articles were also read to identify any further studies that met inclusion criteria—this did not result in any additional articles.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of articles meeting search criteria, number of articles excluded, and final number of articles meeting inclusion criteria for review.

Articles that discussed a program in response to food insecurity but did not measure food insecurity (for example References [42,43]) were excluded, as were other systematic reviews (for example References [17,20,44,45]) and narrative reviews [46]. As we were interested in all studies that purported to measure food insecurity in Australia, studies that discussed food insecurity, as either the standard measured construct or as a construct created by the authors but termed food insecurity, were included. While the food aid sector in Australia reports on food insecurity, (for example References [19,47]), these reports generally do not include a complete description of the method used to collect data and often use food bank attendance as a proxy for national food insecurity level; these reports have therefore been excluded from this review.

Data were extracted from each article by two authors (FHM and BCH). Data were extracted into a spreadsheet that allowed for the capture of specific information across all included articles. Data extracted at this stage included: State; Location; Population group; Findings; Testing an intervention (Y/N); Primary method; Measured food security (Y/N); Method for determining food insecurity; Prevalence of food insecurity; Participant numbers; and Participant description.

3. Results

The search identified 2849 articles, of which 1290 were duplicates. The titles and abstracts of the remaining 1559 articles were read, with 1389 articles excluded as they did not refer, either directly or indirectly, to food insecurity research in Australia, leaving 170 articles for further investigation. The full text of the 170 articles were reviewed; of these, 17 articles were excluded as they were identified as review articles, and 97 articles were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria on closer inspection. The remaining 57 studies have been included in this review (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of 57 studies included in systematic review.

3.1. General Characteristics

Participant numbers in studies reviewed ranged in size from the smallest study with only six participants [48] to population level studies with over 57,000 participants [32]. Most food insecurity research was conducted in the state of Victoria, where 18 studies were conducted, followed by NSW and Western Australia, with nine studies each (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of 57 studies included in a systematic review of the measurement of food insecurity in Australia.

Studies employed a range of methods. Two thirds of studies (n = 38) employed a quantitative methodology, utilizing a survey or audit [1,2,7,16,34,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81], while the remainder (n = 18) were qualitative. Thirteen studies used interviews [41,67,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91], four studies employed focus groups [48,92,93,94], and one utilized photo voice [95].

3.2. Food Insecurity Measurement

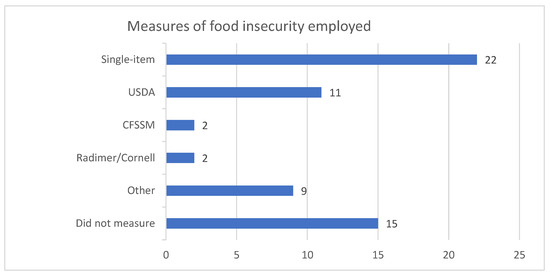

Thirty-three studies directly measured food insecurity (see Figure 3). The most common way to measure food insecurity was via the single item: “In the last 12 months, were there any times that you ran out of food and couldn’t afford to buy more?” This question has been criticized by many researchers for regularly under-reporting food insecurity in population-based studies [7,34]. This question (or a slight variation) was included in 22 studies [1,7,32,50,51,52,54,56,58,61,62,63,64,66,70,71,72,73,77,79,80,92]. Food insecurity measured by the single item ranged from 2.0%, reported in a study of older Australians [52], to 76%, reported in a study of food availability in remote Aboriginal communities [58].

Figure 3.

Tools used to measure food insecurity in the studies included in this systematic review.

Eleven studies included some form of the HFSSM. For example, Allen and Wilson [54] used four questions from the HFSSM, Hughes et al. [61] utilized the 8-item tool (excluding the questions relating to child hunger) as well as the single item question as above, as did Crawford et al. [92] who, in addition to the single item and the HFSSM, also included a question relating to finding food in other places, such as friends or drop-in meal programs. Gichunge et al. [60], Ramsey et al. [16], Kleve et al. [33], and Gallegos, Ramsey, and Ong [59] used the full 18-item tool, while Nolan et al. [7], and Ramsey et al. [16] describe using a 16-item scale (that is the 18-item scale without the two frequency questions). Kleve et al. [33] also included the new Household Food and Nutrition Security Survey (HFNSS). Both McKay and Dunn [2] and Micevski, Thornton, and Brockington [65] used the 6-item USDA tool, plus a follow-up question around hunger. Food insecurity measured by the USDA tool (or variants) ranged from 18% in a population of resettled African refugees in Queensland reported in a study by Gichunge et al. [60], to over 90% in a population of asylum seekers using a food bank in Victoria reported in a study by McKay and Dunn [2].

The Radimer/Cornell instrument was used in two articles [68,69]. These two articles report on the same dataset, where 13% of the population were identified as food insecure.

Three studies compared food insecurity status between the USDA HFSSM and the single item [7,61,92]. Crawford et al. [92] used a nine-item version of the USDA HFSSM with a 30-day reference period, finding 70% of young people experiencing homelessness were food insecure, compared to 58% of the same population who were experiencing food insecurity when measured by the single item question with a 12-month reference period. Hughes et al. [61] compared food insecurity prevalence against the 8-item HFSSM and the single item, with results indicating 46% and 12.7%, respectively. Nolan et al. [7] employed the 18-item USDA HFSSM and the single item question to measure food insecurity among disadvantage populations, finding a higher prevalence with the HFSSM than the single item, 21.9% and 15.8%, respectively. Allen and Wilson [54] used a modified version of the USDA HFSSM including just four items in addition to the single item question; however, given only four questions were included from the USDA HFSSM, a score for food insecurity could not be calculated from this scale, with the prevalence reported for each individual score. Kleve et al. [34] compared the USDA HFSSM with the new Household Food and Nutrition Security Survey (HFNSS), finding the HFNSS reporting higher food insecurity compared to the HFSSM, 57% and 29%, respectively, providing further evidence that the USDA HFSSM may be underreporting food insecurity in Australia.

In addition, ten studies included a proxy measure of food insecurity, but were unable to describe prevalence. For example, in a study investigating the lived experiences of food insecurity among Aboriginal people with disabilities, Spurway and Soldatic [85] asked questions about alternative food access, including fishing and crabbing, with the assumption that all Aboriginal people were food insecure and were using these alternatives as a way to mitigate this insecurity. Wicks, Trevena, and Quine [83] asked urban soup kitchen customers questions about severity and frequency of hunger. Almost 80% described going an entire day without food, and this result was used as a proxy for food insecurity. Burns et al. [56] measured two indicators (i.e., financial and physical restriction) of food insecurity, finding no evidence between financial food insecurity and the purchase of fruit and vegetables, or nutritionally recommended foods, though there was some evidence to suggest that financial and physical restrictions were associated with more frequent purchasing of chain-brand fast food. Cuesta-Briand, Saggers, and McManus [94] investigated access to food through focus groups and interviews for those living with type 2 diabetes. Edmond et al. [74] provided an indication of food security by asking participants about the foods they had consumed in the past 24 h and if they had sought any information about food security. Godrich et al. [91] and Godrich et al. [81] investigated determinants of food insecurity through surveys and interviews with caregivers as a way to determine if children were receiving sufficient nutrition. Friel et al. [51] used the indicative question from the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey: ‘Since the beginning of this year, did you go without meals because of a shortage of money?’ to identify the relationship between food insecurity and drought, finding that among people living in drought-affected areas, those who consumed more discretionary food items were more likely to experience distress. Lindberg, Lawrence, and Caraher [41] asked users of food aid about their experiences of going without food, budgeting, and their use of food charities as a way to understand food insecurity, finding that charitable food services are an important part of the food security safety net. Finally, Pollard et al. [67] investigated issues related to supply chains and food retailers to gain an understanding of observed or assumed food insecurity, finding that supply-chain issues result in increased food costs, and as a result, increased food insecurity in remote populations.

Two studies reported on food security outcomes but did not report on data collection measures. Crawford et al. [57] reported on structural barriers to achieving food security by homeless young people in Australia; however, there was no mention of the measurement of food insecurity or reporting of food insecurity status for this group within the article. Myers et al. [96] reported that 13% of supported playgroup families were food insecure compared to only 5% of mainstream playgroup families; however, there was no mention of how this information was collected in the article.

3.3. Investigation of Food Insecurity in Different Population Groups

The articles reviewed focused on a range of populations. Eight studies measured food insecurity in the general Australian public [7,32,34,50,51,54,56,77]. These studies were typically a secondary analysis of national or state-based population level surveys. Six of these studies used the single item question to indicate food insecurity. Two studies that reported on the single item from Australia wide data reported different rates of food insecurity, with Friel et al. [51] using the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) data from 2007 to report food insecurity of 1.6% and Temple [71] using the National Health Survey of 2005 to report food insecurity at 5.1%. Two studies investigated food insecurity in Victoria; Burns et al. [56] used the single item question from the VicLANES data which sampled from metropolitan Melbourne finding food insecurity at 8.1%, while Kleve et al. [32] used the single item question from the Victorian Population Health Survey (2006–2009) finding food insecurity between 4.9%–5.5%. Using the single item question from their respective state-based population health surveys, Foley et al. [50] found food insecurity at 7.0% in South Australia, while Lê et al. [77] found food insecurity at 5% in north eastern Tasmania. Using the USDA HFSSM for their population level studies, Allen and Wilson [54] did not report a single score as they used a truncated scale, while Kleve et al. [34] reported food insecurity of 29% based on the USDA HFSSM and 57% using the HFNSS. Seven studies reported on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders [58,63,64,67,73,74,95]; these studies investigated the food insecurity situation for both urban and rural Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. Four studies measured food insecurity using the single item [58,63,64,73], with food insecurity ranging from 76% in a remote area of the Northern Territory, to 20.3% in Victoria. The remaining three studies investigating food insecurity among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders did not include a measure of food insecurity, instead investigating experiences of food [95], alternative access to foods [85], and the experience of receiving advice about food insecurity [74].

Ten studies reported on children or young people [49,53,55,57,76,82,86,90,92,93]; however, only three of these studies measured and reported on food insecurity with findings ranging from 70% food insecure [92] to 20.1% food insecure [76]. Three studies reported on university students [59,61,65], all finding higher rates of food insecurity among students than the general population. Five reported on older people [52,68,69,70,79], with food insecurity ranging from 2% to 13%. Refugees and asylum seekers were the focus of three studies [1,2,60] where food insecurity ranged from 18% to 91%, this large range could be ascribed to the ability of asylum seekers and refugees on different visas to access financial support. Finally, two articles focused on those accessing food banks [40,83], neither of these studies measured food insecurity directly, however, both reported that users of food banks employed a range of strategies to mitigate hunger.

3.4. Interventions to Mitigate Food Insecurity

Of the 56 articles reviewed, only five reported on an intervention that was aimed at limiting or reducing food insecurity [48,55,82,87,90]; an additional four studies reported on research collected within an intervention but did not report on the intervention itself [58,62,76,93]. One study reported on the evaluation of a social café meals program aimed at reducing food insecurity and improving social inclusion [87], with findings suggesting that participating in the program increased access to food, with the café setting identified as important in promoting community cohesion. Another reported on the evaluation of a Food Cent$ pilot program [48], a program designed to illustrate the financial benefits of healthy eating. This evaluation found that Food Cent$ could potentially increase knowledge about nutrition, however, the small sample size (n = 6) is a limitation making it difficult to identify causal links. Two studies reported on FoodMate, a program focused on improving food literacy as a way to improve food security. An evaluation of the pilot returned largely inconclusive results, attributed to high attrition rates with the authors highlighting the difficulties in including people at risk in long-term programs [55]. The second paper to evaluate this program included past FoodMate program graduates and found that the increased nutrition knowledge gained through the program could lead to increased food security; however, this study was also small, with only 10 participants [90]. Finally, a study investigating the role of a community meals program operating for Aboriginal people in Victoria through interviews with 23 staff, found that such programs may offer access to safe, affordable, nutritious food that is also culturally and socially acceptable; however, sustainability of the program was identified as an ongoing problem [82].

4. Discussion

This review has investigated the breadth of food insecurity research in Australia, finding that over the past 15 years researchers have focused on a range of populations including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, refugees and asylum seekers, older and younger populations, university students, and those receiving charitable food assistance. Researchers have used a range of tools to measure food insecurity, from the validated and reliable USDA HFSSM, to the less reliable single item measure. Of concern to the authors were the number of studies that purported to measure food insecurity, but used a proxy measure, a non-valid measure or failed to mention the data collection methods in sufficient detail, if at all. Given the already limited amount of information relating to food insecurity in Australia, this lack of research rigor is of great concern.

Various single-item and multi-item tools have been developed to determine the prevalence of food insecurity at a population level. As shown in this review, the measurement of food insecurity in Australia is commonly limited to a single item asking whether anyone in a household has run out of food in the preceding 12 months and has been unable to purchase more due to a lack of money. This review found food insecurity as identified by this question ranged from 2.0% in older Australians [52] to 76% in remote Aboriginal communities [58]. Australian studies suggest that the single-item measure underestimates the prevalence of food insecurity by at least 5% [7], compared with more comprehensive multi-item measures [34,57,61]. The use of this single item in the Australian Health Survey has consistently reported a national level of food insecurity of approximately 5%; due to this low prevalence, food insecurity data are not routinely collected in Australia—in the past decade, food security has only been measured twice; in 2004–2005 and 2011–2012.

Given the limitations of the single-item food security measurement tool, the more sensitive, multi-item tool developed by the USDA is commonly used to estimate food insecurity prevalence and severity [7,20]. The 18-item USDA HFSSM can determine severity and prevalence of food insecurity and was identified as being employed in eleven studies included in this review. This tool takes into consideration the multi-dimensional nature of food insecurity, typically within a 12-month reference period; however, it is also valid for a 6-month or 30-day reference period, and exhibits good reliability (based on a Cronbach’s alpha greater than 0.70) [97].

Given the different methods for data collection, including the wide range of tools used to measure food insecurity, and the different population groups targeted, it is difficult to compare the reported food insecurity across the 57 studies included in this review. However, in general, this review identified a higher prevalence of food insecurity in studies employing the HFSSM—from 18% [60], to over 90% [2], compared with those using the single item—with findings of food insecurity from 2.0%, [52], to 76% [58], with the highest food insecurity reported in populations of people seeking asylum [2] and remote Aboriginal populations [58].

While the HFSSM has been validated in the USA, where it has been shown to provide accurate measures of food insecurity with the capability to distinguish between varying degrees of food insecurity, it has a number of limitations for use in Australia [98]. This tool focuses on a single dimension of food insecurity (affordability), and not the other three, equally important dimensions, which limits its applicability to the broader Australian context of food insecurity, where access, utilization, and sustainability are key considerations of food insecurity. In addition to affordability, food security in Australia is influenced by the presence of food deserts [99], challenges with transport to food stores [56], regionality and availability of foods in remote areas [100], the nature of the retail environment [101], the welfare and employment system [8], and the availability of culturally appropriate foods [2], all things that need to be taken into consideration when reporting on food insecurity at a population level. The HFSSM is also unable to identify food security at the individual level, rather measuring food insecurity at the household level, potentially hiding individual differences in severity of experienced food insecurity among members of a household. The 12-month reference period also limits the ability of the instrument in capturing severe but short-term hunger [35]. As such, there remains a gap for a novel tool that can measure the experience of food insecurity in the Australian context.

Several limitations within the studies reviewed have been identified. A number of studies had very small sample sizes, making it very difficult to generalize results [41,48,55,85,86,87,88,89,95]. Poor response rates were reported by several studies; for example, Gallegos, Ramsey, and Ong [59] only received a response rate of 6.7%, while Barbour et al. [55] reported more than half of participants were lost on follow-up. Other studies had methodological problems, for example as acknowledged by Allen et al. [87], interviews in their study were brief and conducted by inexperienced researchers, with data saturation not reached. Finally, it should be noted that there have been no longitudinal studies conducted in Australia to investigate the long-term impacts or experiences of food insecurity.

Limitations

There are some limitations of this review that should also be acknowledged. While every attempt was made to ensure this review was comprehensive, additional articles may have been missed. Given that this is the first review of its kind, with the inclusion of several databases and broad key terms, the authors are confident that there is little information that is not presented here. Given the variety of approaches taken to measure food insecurity, there are challenges in comparing the outcomes of different studies. However, as this is not a meta-analysis, the authors do not feel this should invalidate the findings.

5. Conclusions

This review is the first of its kind to investigate the breath and scope of food security research conducted in Australia. This research found that researchers are using a variety of methods to collect information about food insecurity, including a single item question that has been found to return an inaccurate measure of food insecurity. As a result of the variety of methods employed, there is little understanding of the true prevalence and severity of food insecurity in Australia. Based on the findings of this review, the authors suggest more work is needed to create a measure of food insecurity that will suit Australia, which will allow researchers to gain a clear understanding of the prevalence of food insecurity in the Australian community.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.H.M., and M.D.; Data curation, F.H.M., B.C.H.; Formal analysis, B.C.H. and F.H.M.; Investigation, F.H.M., and B.C.H.; Methodology, F.H.M., and M.D.; Project administration, F.H.M.; Supervision, F.H.M.; Writing—original draft, F.H.M.; Writing—review & editing, F.H.M., M.D., and B.C.H.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gallegos, D.; Ellies, P.; Wright, J. Still there’s no food! Food insecurity in a refugee population in Perth, Western Australia. Nutr. Dietet. 2008, 65, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, F.H.; Dunn, M. Food security among asylum seekers in Melbourne. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2015, 39, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. Rome declaration on the world food security and world food summit plan of action. In Proceedings of the World Food Summit 1996, Rome, Italy, 13–17 November 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, R.; Schoeneberger, H.; Pfeifer, H.; Preuss, H.-J. The four dimensions of food and nutrition security: Definitions and concepts. SCN News 2000, 20, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, A.; Olson, C.M.; Frongillo, E.A., Jr. Validation of the Radimer/Cornell measures of hunger and food insecurity. J. Nutr. 1995, 125, 2793–2801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Webb, P.; Coates, J.; Frongillo, E.A.; Rogers, B.L.; Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Measuring household food insecurity: Why it’s so important and yet so difficult to do. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1404S–1408S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolan, M.; Rikard-Bell, G.; Mohsin, M.; Williams, M. Food insecurity in three socially disadvantaged localities in Sydney, Australia. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2006, 17, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, H.; McKay, F.H. Food as a discretionary item: The impact of welfare payment changes on low-income single mother’s food choices and strategies. J. Poverty Soc. Justice 2017, 25, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, H.K.; Laraia, B.A.; Kushel, M.B. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, R.C.; Phillips, S.M.; Orzol, S.M. Food insecurity and the risks of depression and anxiety in mothers and behavior problems in their preschool-aged children. Pediatrics 2006, 118, e859–e868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.T.; Frank, D.A.; Levenson, S.M.; Neault, N.B.; Heeren, T.C.; Black, M.M.; Berkowitz, C.; Casey, P.H.; Meyers, A.F.; Cutts, D.B. Child food insecurity increases risks posed by household food insecurity to young children’s health. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1073–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-Jacobs, R.; Black, M.M.; Casey, P.H.; Cook, J.T.; Cutts, D.B.; Chilton, M.; Heeren, T.; Levenson, S.M.; Meyers, A.F.; Frank, D.A. Household food insecurity: Associations with at-risk infant and toddler development. Pediatrics 2008, 121, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Tarasuk, V. Food Insecurity Is Associated with Nutrient Inadequacies among Canadian Adults and Adolescents. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M.A.; Lippert, A.M. Feeding her children, but risking her health: The intersection of gender, household food insecurity and obesity. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 1754–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daponte, B.O.; Lewis, G.H.; Sanders, S.; Taylor, L. Food pantry use among low-income households in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. J. Nutr. Educ. 1998, 30, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, R.; Giskes, K.; Turrell, G.; Gallegos, D. Food insecurity among adults residing in disadvantaged urban areas: Potential health and dietary consequences. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazerghi, C.; McKay, F.H.; Dunn, M. The role of food banks in addressing food insecurity: A systematic review. J. Community Health 2016, 41, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, F.H.; McKenzie, H. Food Aid Provision in Metropolitan Melbourne: A Mixed Methods Study. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2017, 12, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foodbank Australia. Foodbank Hunger Report; Foodbank Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby, S.; Kleve, S.; McKechnie, R.; Palermo, C. Measurement of the dimensions of food insecurity in developed countries: A systematic literature review. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 2887–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, W.L.; Cook, J.T. Household food security in the United States in 1995: Technical Report of the Food Security Measurement Project; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1997.

- Melgar-Quinonez, H.; Nord, M.; Perez-Escamilla, R.; Segall-Correa, A. Psychometric properties of a modified US-household food security survey module in Campinas, Brazil. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 62, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgar-Quinonez, H.; Hackett, M. Measuring household food security: The global experience. Revista de Nutrição 2008, 21, 27s–37s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, M.; Zubieta, A.C.; Hernandez, K.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H. Food insecurity and household food supplies in rural Ecuado. Archivos Latinoamericanos de Nutricion 2007, 57, 10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Frongillo, E.A.; Chowdhury, N.; Ekström, E.-C.; Naved, R.T. Understanding the experience of household food insecurity in rural Bangladesh leads to a measure different from that used in other countries. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 4158–4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frongillo, E.A.; Nanama, S. Development and validation of an experience-based measure of household food insecurity within and across seasons in northern Burkina Faso. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1409S–1419S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballard, T.J.; Kepple, A.W.; Cafiero, C. The Food Insecurity Experience Scale: Development of a Global Standard for Monitoring Hunger Worldwide; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cafiero, C.; Nord, M.; Viviani, S. Methods for Estimating Comparable Prevalence Rates of Food Insecurity Experienced by Adults Throughout the World; VoH Technical Reprt No 1/2016; UN FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Frongillo, E.A.; Nguyen, H.T.; Smith, M.D.; Coleman-Jensen, A. Food Insecurity Is Associated with Subjective Well-Being among Individuals from 138 Countries in the 2014 Gallup World Poll. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.D. Food insecurity and mental health status: A global analysis of 149 countries. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.D.; Rabbitt, M.P.; Coleman-Jensen, A. Who are the world’s food insecure? New evidence from the Food and Agriculture Organization’s food insecurity experience scale. World Dev. 2017, 93, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABS. National Health Survey 2014–2015. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/4364.0.55.0092011-12?OpenDocument (accessed on 26 January 2019).

- Kleve, S.; Gallegos, D.; Ashby, S.; Palermo, C.; McKechnie, R. Preliminary validation and piloting of a comprehensive measure of household food security in Australia. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKechnie, R.; Turrell, G.; Giskes, K.; Gallegos, D. Single-item measure of food insecurity used in the National Health Survey may underestimate prevalence in Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2018, 42, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radimer, K.L.; Radimer, K.L. Measurement of household food security in the USA and other industrialised countries. Public Health Nutr. 2002, 5, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radimer, K.L.; Olson, C.M.; Greene, J.C.; Campbell, C.C.; Habicht, J.-P. Understanding hunger and developing indicators to assess it in women and children. J. Nutr. Educ. 1992, 24, 36S–44S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, L.J.; Hadley, C. Moving beyond hunger and nutrition: A systematic review of the evidence linking food insecurity and mental health in developing countries. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2009, 48, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruening, M.; Argo, K.; Payne-Sturges, D.; Laska, M.N. The struggle is real: A systematic review of food insecurity on postsecondary education campuses. J. Acad. Nutr. Dietet. 2017, 117, 1767–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, E.S.; Reichenheim, M.E.; de Moraes, C.L.; Antunes, M.M.; Salles-Costa, R. Household food insecurity: A systematic review of the measuring instruments used in epidemiological studies. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 877–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindberg, R.; Lawrence, M.; Caraher, M. Kitchens and Pantries—Helping or Hindering? The Perspectives of Emergency Food Users in Victoria, Australia. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2017, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, L.M.; Chester, M.R.; Aberle, L.M.; Bobongie, V.J.A.; Davies, C.; Godrich, S.L.; Milligan, R.A.K.; Tartaglia, J.; Thorne, L.M.; Begley, A. Foodbank of Western Australia’s healthy food for all. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1490–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furber, S.; Quine, S.; Jackson, J.; Laws, R.; Kirkwood, D. The role of a community kitchen for clients in a socio-economically disadvantaged neighbourhood. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2010, 21, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacovou, M.; Pattieson, D.C.; Truby, H.; Palermo, C. Social health and nutrition impacts of community kitchens: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, F.H.; Lippi, K.; Dunn, M. Investigating Responses to Food Insecurity Among HIV Positive People in Resource Rich Settings: A Systematic Review. J. Community Health 2017, 42, 1062–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindberg, R.; Whelan, J.; Lawrence, M.; Gold, L.; Friel, S. Still serving hot soup? Two hundred years of a charitable food sector in Australia: A narrative review. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2015, 39, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SecondBite. SecondBite 2015–16 Annual Report; SecondBite: Kensington, VIC, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bassett, H.; Lloyd, C.; King, R. Food Cent$: Educating Mothers with a Mental Illness about Nutrition. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2003, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleve, S.; Davidson, Z.; Gearon, E.; Booth, S.; Palermo, C. Are low-to-middle-income households experiencing food insecurity in Victoria, Australia? An examination of the Victorian Population Health Survey, 2006–2009. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2017, 23, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, S. Eating rough: Food sources and acquisition practices of homeless young people in Adelaide, South Australia. Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, W.; Ward, P.R.; Carter, P.; Coveney, J.; Tsourtos, G.; Taylor, A. An ecological analysis of factors associated with food insecurity in South Australia, 2002–7. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friel, S.; Berry, H.; Dinh, H.; O’Brien, L.; Walls, H.L. The impact of drought on the association between food security and mental health in a nationally representative Australian sample. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quine, S.; Morrell, S. Food insecurity in community-dwelling older Australians. Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsey, R.; Giskes, K.; Turrell, G.; Gallegos, D. Food insecurity among Australian children: Potential determinants, health and developmental consequences. J. Child Health Care 2011, 15, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, M.W.; Wilson, M. Materialism and food security. Appetite 2005, 45, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, L.; Ho, M.Y.L.; Davidson, Z.E.; Palermo, C. Challenges and opportunities for measuring the impact of a nutrition programme amongst young people at risk of food insecurity: A pilot study. Nutr. Bull. 2016, 41, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, C.; Bentley, R.; Thornton, L.; Kavanagh, A. Associations between the purchase of healthy and fast foods and restrictions to food access: A cross-sectional study in Melbourne, Australia. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, B.; Yamazaki, R.; Franke, E.; Amanatidis, S.; Ravulo, J.; Steinbeck, K.; Ritchie, J.; Torvaldsen, S. Sustaining dignity? Food insecurity in homeless young people in urban Australia. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2014, 25, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M.; Brown, C.; Georga, C.; Miles, E.; Wilson, A.; Brimblecombe, J. Traditional food availability and consumption in remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory, Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2017, 41, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallegos, D.; Ramsey, R.; Ong, K.W. Food insecurity: Is it an issue among tertiary students? Higher Educ. 2014, 67, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gichunge, C.; Harris, N.; Tubei, S.; Somerset, S.; Lee, P. Relationship between food insecurity, social support, and vegetable intake among resettled African refugees in Queensland, Australia. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2015, 10, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.; Serebryanikova, I.; Donaldson, K.; Leveritt, M. Student food insecurity: The skeleton in the university closet. Nutr. Dietet. 2011, 68, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Ming, W.; Flood, V.M.; Simpson, J.M.; Rissel, C.; Baur, L.A. Dietary behaviours during pregnancy: Findings from first-time mothers in southwest Sydney, Australia. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markwick, A.; Ansari, Z.; Sullivan, M.; McNeil, J. Social determinants and lifestyle risk factors only partially explain the higher prevalence of food insecurity among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in the Australian state of Victoria: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markwick, A.; Ansari, Z.; Sullivan, M.; Parsons, L.; McNeil, J. Inequalities in the social determinants of health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: A cross-sectional population-based study in the Australian state of Victoria. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micevski, D.; Thornton, L.; Brockington, S. Food insecurity among university students in Victoria: A pilot study. Nutr. Dietet. 2014, 71, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucheru, D.; Hanlon, M.C.; Campbell, L.E.; McEvoy, M.; MacDonald-Wicks, L. Social dysfunction and diet outcomes in people with psychosis. Nutrients 2017, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, C.M.; Nyaradi, A.; Lester, M.; Sauer, K. Understanding food security issues in remote Western Australian Indigenous communities. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2014, 25, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.; Flood, V.; Yeatman, H.; Mitchell, P. Prevalence and risk factors of food insecurity among a cohort of older Australians. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2014, 18, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, J.; Flood, V.; Yeatman, H.; Wang, J.J.; Mitchell, P. Food insecurity and poor diet quality are associated with reduced quality of life in older adults. Nutr. Dietet. 2016, 73, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, J.B. Food insecurity among older Australians: Prevalence, correlates and well-being. Australas. J. Ageing 2006, 25, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, J.B. Severe and moderate forms of food insecurity in Australia: Are they distinguishable? Aust. J. Soc. Issues (Aust. Counc. Soc. Serv.) 2008, 43, 649–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, C.; Bentley, R.; Thornton, L.; Kavanagh, A. Reduced food access due to a lack of money, inability to lift and lack of access to a car for food shopping: A multilevel study in Melbourne, Victoria. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 14, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, J.; Paradies, Y.C. Socio-demographic factors and psychological distress in Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australian adults aged 18-64 years: Analysis of national survey data. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmond, K.M.; McAuley, K.; McAullay, D.; Matthews, V.; Strobel, N.; Marriott, R.; Bailie, R. Quality of social and emotional wellbeing services for families of young Indigenous children attending primary care centers; a cross sectional analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evers, A.; Hodgson, N.L. Food choices and local food access among Perth’s community gardeners. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 585–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godrich, S.; Lo, J.; Davies, C.; Darby, J.; Devine, A. Prevalence and socio-demographic predictors of food insecurity among regional and remote Western Australian children. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2017, 41, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lê, Q.; Auckland, S.; Nguyen, H.B.; Murray, S.; Long, G.; Terry, D.R. The socio-economic and physical contributors to food insecurity in a rural community. SAGE Open 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, A.; Brown, G.; Maycock, B. Western Australian food security project. BMC Public Health 2007, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radermacher, H.; Feldman, S.; Bird, S. Food Security in Older Australians from Different Cultural Backgrounds. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2010, 42, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornton, L.E.; Pearce, J.R.; Ball, K. Sociodemographic factors associated with healthy eating and food security in socio-economically disadvantaged groups in the UK and Victoria, Australia. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godrich, S.L.; Lo, J.; Davies, C.R.; Darby, J.; Devine, A. Which food security determinants predict adequate vegetable consumption among rural Western Australian children? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, M.; Bonnell, E.; Thorpe, S.; Browne, J.; Barbour, L.; MacDonald, C.; Palermo, C. Sharing the tracks to good tucker: Identifying the benefits and challenges of implementing community food programs for Aboriginal communities in Victoria. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2014, 20, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicks, R.; Trevena, L.J.; Quine, S. Experiences of food insecurity among urban soup kitchen consumers: Insights for improving nutrition and well-being. J. Am. Dietet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 921–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, C.; Baldwin, C. Critiquing Food Security Inter-governmental Partnership Approaches in Victoria, Australia. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2017, 76, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurway, K.; Soldatic, K. “Life just keeps throwing lemons”: The lived experience of food insecurity among Aboriginal people with disabilities in the West Kimberley. Local Environ. 2016, 21, 1118–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, S.; Coveney, J. Survival on the Streets: Prosocial and Moral Behaviors Among Food Insecure Homeless Youth in Adelaide, South Australia. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2007, 2, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L.; O’Connor, J.; Amezdroz, E.; Bucello, P.; Mitchell, H.; Thomas, A.; Kleve, S.; Bernardi, A.; Wallis, L.; Palermo, C. Impact of the Social Café meals program: A qualitative investigation. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2014, 20, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; Lawrence, G. Flooding and food security: A case study of community resilience in Rockhampton. Rural Soc. 2014, 23, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, I.R.; Ward, P.R.; Coveney, J. Food insecurity in South Australian single parents: An assessment of the livelihoods framework approach. Crit. Public Health 2011, 21, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiklejohn, S.J.; Barbour, L.; Palermo, C.E. An impact evaluation of the FoodMate programme: Perspectives of homeless young people and staff. Health Educ. J. 2017, 76, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godrich, S.L.; Davies, C.R.; Darby, J.; Devine, A. What are the determinants of food security among regional and remote Western Australian children? Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2017, 41, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, B.; Yamazaki, R.; Franke, E.; Amanatidis, S.; Ravulo, J.; Torvaldsen, S. Is something better than nothing? Food insecurity and eating patterns of young people experiencing homelessness. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2015, 39, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunson, J.S.; Warin, M.; Moore, V. Visceral politics: Obesity and children’s embodied experiences of food and hunger. Crit. Public Health 2017, 27, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta-Briand, B.; Saggers, S.; McManus, A. ‘You get the quickest and the cheapest stuff you can’: Food security issues among low-income earners living with diabetes. Australas. Med. J. 2011, 4, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.; Burns, C.; Liebzeit, A.; Ryschka, J.; Thorpe, S.; Browne, J. Use of participatory research and photo-voice to support urban Aboriginal healthy eating. Health Soc. Care Community 2012, 20, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.; Gibbons, K.; Arnup, S.; Volders, E.; Naughton, G. Early childhood nutrition, active outdoor play and sources of information for families living in highly socially disadvantaged locations. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2015, 51, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickel, G.; Nord, M.; Price, C.; Hamilton, W.; Cook, J. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security; Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service: Alexandria, Egypt, 2000.

- Jones, A.D.; Ngure, F.M.; Pelto, G.; Young, S.L. What are we assessing when we measure food security? A compendium and review of current metrics. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2013, 4, 481–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coveney, J.; O’dwyer, L.A. Effects of mobility and location on food access. Health Place 2009, 15, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scelza, B.A. Food scarcity, not economic constraint limits consumption in a rural Aboriginal community. Aust. J. Rural Health 2012, 20, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollard, C.M.; Landrigan, T.; Ellies, P.; Kerr, D.A.; Lester, M.; Goodchild, S. Geographic factors as determinants of food security: A Western Australian food pricing and quality study. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 23, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).