Implementation of Health Promotion Competencies in Ireland and Italy—A Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

Background

2. Materials and Methods

- the highest number of responses to the online survey were received from respondents in these countries [12]

- the ‘outer setting’ construct with particular reference to Health Promotion infrastructure and capacity at country level.

- the ‘inner setting’ construct applied at country level with emphasis on the subconstructs of readiness to implement resources and support.

- the implementation process construct, including the subconstructs of planning, use, champions, leadership, reflection and evaluation.

- accessing evidence from different sources (i.e., documents, reports, informants, national experts).

- using different methods (i.e., documentary analysis, interviews and thematic analysis).

- including national experts’ comments in the final analysis of findings.

2.1. Sample

2.2. Methods

2.3. Desk Review

2.4. Semi-Structured Interviews

2.5. Collation and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Desk Review

- Land area—Ireland 69,800 km2; Italy 302,100 km2

- Population—Ireland 4.63 million; Italy 60.8 million [28]

3.2. Interviews and Informants

3.3. Implementing the CompHP Competencies in Ireland and Italy

3.3.1. Readiness to Implement—Ireland

‘on a scale of 1-10 Ireland is at 6 … people realize that this is what we need to define our role.’

‘at least 50/50 willingness/readiness to implement the CompHP Competencies nationally.’

‘maybe contemplation stage … parts of Ireland where they are just thinking about it.’

3.3.2. Readiness to implement—Italy

‘very early in process … slow and difficult to involve people at national and regional level … a lot of work’

‘we need wider diffusion about them and more time to do that before being ready to implement.’

3.3.3. Implementation—Ireland

3.3.4. Implementation—Italy

‘I do not name the CompHP framework … I talk about them, but I do not name them.’

3.3.5. Impact

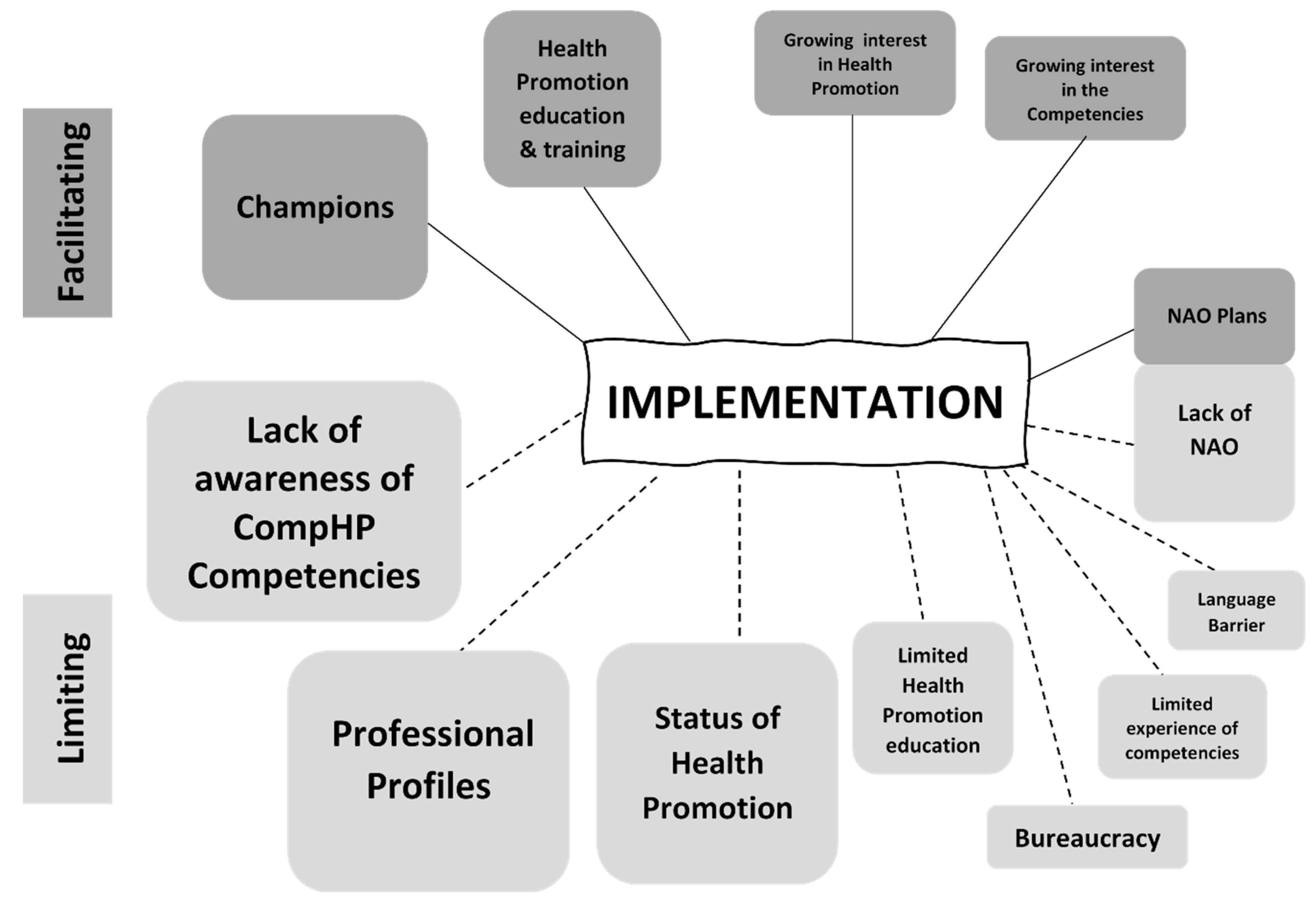

3.4. Factors Influencing the Implementation of the CompHP Competencies in Ireland

3.5. Factors Faciliting Implemention in Ireland

3.5.1. Health Promotion Professional Association/National Accreditation Organization (NAO)

‘the Association has done hugely valuable work on the CompHP Competencies … there is a momentum behind it.’

‘as you see more registration you will see the CompHP Competencies becoming more embedded in people’s thinking and practice.’

3.5.2. Potential for Statutory Recognition

‘to have our own competencies and registration in place is a good stepping-stone towards statutory with CORU (https://www.coru.ie/) and registration down the line.’

3.5.3. Health Promotion Education

‘the more embedded and centered work and experiences is around the CompHP Competencies at the educational level the more widely understood and used they will become.’

3.5.4. Health Promotion Workforce

‘I think a competency framework is like a safety blanket or a protection and definition of what we do in a very succinct way.’

‘people who are working on the ground are keen for this (implementation) to happen … they see the value in the CompHP Competencies.’

3.6. Factors both facilitating and limiting implemention in Ireland

‘I think the competencies can offer a context for a conversation that might need to be had in terms of what the role and function of Health Promotion is in the new structure.’

‘the national leadership in Health Promotion in the service will have a much different role … so maybe there is an opportunity for more buy-in of the competencies … equally there might be more resistance.’

3.7. Factors Limiting Implmentation in Ireland

3.7.1. Lack of Awareness of the CompHP Competencies

3.7.2. Status of Health Promotion

‘where Health Promotion is ‘at’, at a policy level, makes a big difference in implementing them as all funding comes through the policy stream.’

‘The term Health Promotion is not used anymore in the health service … it’s now ‘health and wellbeing’… this hinders the uptake of the competencies and registration.’

‘In our organization (NGO) we have a prevention department … it used to be called the Health Promotion department … not sure what that means for the competencies.’

3.7.3. Professional Status

‘it appears that anybody without a professional qualification in Health Promotion or without experience is entitled to, and has the ability to, do Health Promotion.’

‘the competencies would need to be linked to grading for our profession and that can be seen as been helpful (to implementation) but also as a hindrance as it hasn’t happened.’

3.8. Factors Influencing the Implementation of the CompHP Competencies in Italy

3.9. Factors Faciliating Implementation in Italy

3.9.1. Champions

‘when we speak about Health Promotion on every occasion we use the CompHP Competencies.’

3.9.2. Health Promotion Education and Training

‘the demand for the competencies will progressively increase as a consequence of more effective Health Promotion training and universities courses.’

3.9.3. Growing Awareness of Health Promotion and the CompHP Competencies

‘recognition of Health Promotion will reach new levels if the CompHP Competencies work to change, or at least begin to change, how the regions operate.’

‘the people we work with … like regions, groups, colleagues … they are very, very interested in the competencies.’

3.10. Factors both Facilitating and Limiting Implementation in Italy

Plans for Developing/Lack of a National Accreditation Organization (NAO)

‘there is a lot of resistance to that … because to people who work in in public health Health Promotion is something that is regarded as a natural part of the public health profession … not a competency that you have to support and improve.’

‘the richer regions will get the System … you will see many regions from the north and less from the south involved.’

3.11. Factors Limiting Implementation in Italy

3.11.1. Lack of Awareness of the CompHP Competencies

‘So far the competencies are not much known and haven’t really influenced at national level’

‘Some aware … but a few people … there isn’t a critical mass for change at national, regional or local level or within the university.’

‘they are not widely known … little spots in different places and these are not linked together.’

3.11.2. Professional Profiles

‘it’s the legal title of the degree … so you can do a profession only if you have this degree … it’s very difficult … it would be an enormous change in legislation (to recognize Health Promotion) … I don’t think it is possible’

‘we cannot ask other people to embrace them (the competencies) because they have other profiles.’

‘you can have Health Promotion registration and know the competencies but unless you have registration and education in a defined area you are not able to apply for public calls.’

‘I don’t think it’s possible to create a Health Promotion practitioner register ... as a profession … because we have a particular legislation about the different professions … most of the people are not agreeing with this kind of definition … to recognize Health Promotion … because different professionals are involved in Health promotion and each single profession has a special register so it’s very, very difficult.’

‘some employers have difficulty recognizing nursing or physiotherapy as a profession like medicine … we are still very medically oriented … so it’s very complicated to work on Health Promotion … but it’s not only with Health Promotion.’

‘Health Promotion professionals … it’s not so widespread in Italy … I think it is better to have a specific Health Promotion module for psychologists, for medical or education practitioners.’

3.11.3. Status of Health Promotion

‘knowledge is very low about Health Promotion and lots of people confuse Health Promotion with prevention or Health Education … so it’s very, very difficult about the competencies.’

3.11.4. Language Barrier

‘if they (the competencies) remain in English and the registration is in English … we have a few people only in Italy (able) to use them.’

‘we will have a NAO for accreditation in Italy because the language is a big wall.’

‘we have difficulties even in translating the word competencies … we should start with what is there and go through it slowly and improve on it.’

3.11.5. Limited Health Promotion education

3.11.6. Bureaucracy

‘In Italy it’s a slow process related to the characteristics of the system … not only the competencies … the system overall is very slow … bureaucracy is a problem.’

3.11.7. Limited Experience of Competency-Based Approaches

‘Competencies as a professional discourse is coming into the professional culture’.

3.12. Future Implementation of the CompHP Competencies

‘The competencies need to become the mentality of the person so that when they use them, they talk to people with passion.’

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allegrante, J.P.; Barry, M.M.; Airhihenbuwa, C.O.; Auld, M.E.; Collins, J.L.; Lamarre, M.C.; Magnusson, G.; McQueen, D.V.; Mittelmark, M.B. Galway Consensus Conference Domains of core competency, standards, and quality assurance for building global capacity in health promotion: The Galway Consensus Conference Statement. Health Educ. Behav. 2009, 36, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, M.M.; Allegrante, J.P.; Lamarre, M.C.; Auld, M.E.; Taub, A. The Galway Consensus Conference: International collaboration on the development of core competencies for health promotion and health education. Glob. Health Promot. 2009, 16, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taub, A.; Allegrante, J.P.; Barry, M.M.; Sakagami, K. Perspectives on Terminology and Conceptual and Professional Issues in Health Education and Health Promotion Credentialing. Health Educ. Behav. 2009, 36, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dempsey, C.; Barry, M.M.; Battel-Kirk, B.; Dempsey, C. The CompHP Project Partners. In The CompHP Core Competencies Framework for Health Promotion; International Union for Health Promotion and Education (IUHPE): Paris, France, 2011; Available online: http://www.iuhpe.org/images/PROJECTS/ACCREDITATION/CompHP_Competencies_Handbook.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Barry, M.M.; Battel-Kirk, B.; Davison, H.; Dempsey, C.; Parish, R.; Schipperen, M.; Speller, V.; van der Zanden, G.; Zilnyk, A.; On Behalf of the CompHP Project Partners. The CompHP Project Handbooks; IUHPE: Paris, France, 2012; Available online: https://www.iuhpe.org/images/PROJECTS/ACCREDITATION/CompHP_Project_Handbooks.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Barry, M.M.; Battel-Kirk, B.; Dempsey, C. The CompHP Core Competencies Framework for Health Promotion in Europe. Health Educ. Behav. 2012, 39, 648–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battel-Kirk, B.; Barry, M.M. Has the development of Health Promotion competencies made a difference?-A scoping review of the literature. Health Educ. Behav. 2019, 46, 824–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battel-Kirk, B.; Barry, M.M.; Taub, A.; Lysoby, L. A review of the international literature on health promotion competencies: Identifying frameworks and core competencies. Glob. Health Promot. 2009, 16, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shilton, T.; Howat, P.; Lower, T.; James, R. Health promotion development and health promotion workforce competency in Australia. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2001, 12, 16–123. [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman, B.; O’Neill, M. The professionalization of health promotion in Canada; Potential risks and rewards. In Health Promotion in Canada–Critical Perspectives on Practice; Rootman, I., Pederson, A., Durpre, S., O’Neill, M., Eds.; Canadian Scholars’ Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Meresman, S.; Colomer, C.; Barry, M.; Davies, J.K.; Lindstrom, S.; Loureiro, I.; Mittelmark, M. Review of professional competencies in health promotion: European perspectives. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 2004, 21, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battel-Kirk, B.; Barry, M.M. Evaluating progress in the uptake and impact of the CompHP Core Competencies on Health Promotion practice, education and training in Europe-Findings from an online survey. Health Promot. Int. 2019, daz068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, K. Health Promotion Competencies Baseline Implementation Survey Report. Health Promotion Forum of New Zealand: Auckland, 2013. Available online: http://www.hauora.co.nz/assets/files/HP%20Competencies%20Implementation%20report.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Health Promotion Forum of New Zealand. A Review of the Use and Future of Health Promotion Competencies for Aotearoa-New Zealand; Health Promotion Forum of New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Battel-Kirk, B.; van der Zanden, G.; Schipperen, M.; Contu, P.; Gallardo, C.; Martinez, A.; Garcia de Sola, S.; Barry, M.M. Developing a Competency-Based Pan-European Accreditation Framework for Health Promotion. Health Educ. Behav. 2012, 39, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simons, H. Case Study Research in Practice; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, G. How to do Your Case Study; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- IUHPE. Health Promotion Accreditation System Global Register. Available online: https://www.iuhpe.org/index.php/en/iuhpe-global-register (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Rodgers, M.; Thomas, S.; Harden, M.; Parker, G.; Street, A.; Eastwood, A. Developing a methodological framework for organizational case studies: A rapid review and consensus development process. Health Serv. Deliv. Res. 2016, 4, 1–170. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26740990 (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Damschroder, L.J.; Aron, D.C.; Keith, R.E.; Kirsh, S.R.; Alexander, J.A.; Lowery, J.C. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Lowery, J.C. Evaluation of a large-scale weight management program using the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR). Implement. Sci. 2013, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keith, R.E.; Crosson, J.C.; O’Malley, A.S.; Cromp, D.; Taylor, E.F. Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to produce actionable findings: A rapid-cycle evaluation approach to improving implementation. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeman, J.; Wiecha, J.L.; Vu, M.; Blitstein, J.L.; Allgood, S.; Lee, S.; Merlo, C. School health implementation tools: A mixed methods evaluation of factors influencing their use. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexis Kirk, M.; Kelley, C.; Yankey, N.; Birken, S.A.; Abadie, B.; Damschroder, L. A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement. Sci. 2015, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research Interview Tool Guide. Available online: http://cfirwiki.net/guide/app/index.html#/ (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union: The EU in Figures. Available online: https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/figures/living_en (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Ireland: Country Health Profile 2019, State of Health in the EU; OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Belgium, Brussels, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Insurance Authority. Market Statistics 2019. Available online: https://www.hia.ie/publication/market-statistics (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Department of Health, Dublin. Available online: https://health.gov.ie (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Health Service Executive (HSE), Dublin. Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Toth, F. Health Care Regionalization in Italy. In Proceedings of the Presentation at 23rd World Congress of Political Science, Montréal, QC, Canada, 19–14 July 2014; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264895778_Health_Care_Regionalization_in_Italy (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Poscia, A.; Silenzi, A.; Ricciardi, W. Organization and Financing of Public Health Services in Europe: Country Reports. In Health Policy Series; Rechel, B., Maresso, A., Sagan, A., Hernández-Quevedo, C., Williams, G., Richardson, E., Jakubowski, E., Nolte, E., Eds.; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018; Volume 49, pp. 49–66. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507328/ (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Department of Health. Healthy Ireland-A Framework for Improved Health and Wellbeing 2013–2025; Department of Health: Dublin, Ireland, 2013; Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/healthwellbeing/healthy-ireland/hidocs/healthyirelandframework.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Ministero della Salute. Guadagnare Salute-Rendere Facili Le Scelte Salutari; Ministero della Salute: Rome, Italy, 2007. Available online: http://www.ccm-network.it/pagina.jsp?id=node/9 (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- HSE, Dublin: Health and Wellbeing. Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/healthwellbeing (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Irish Cancer Society. Available online: https://www.cancer.ie/ (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Irish Heart Foundation. Available online: https://irishheart.ie/ (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Mental Health Ireland. Available online: https://www.mentalhealthireland.ie/ (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- IUHPE. Health Promotion Accreditation System Global Register Accredited courses. Available online: https://www.iuhpe.org/index.php/en/iuhpe-global-register/iuhpe-accredited-courses (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Institute of Technology Sligo, Ireland. MSc Health Promotion Practice. Available online: https://www.itsligo.ie/courses/msc-health-promotion-online/ (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Waterford Institute of Technology, Ireland. MA in Advanced Facilitation Skills for Promoting Health and Well Being. Available online: https://www.wit.ie/courses/ma-in-advanced-facilitation-skills-for-promoting-health-and-well-being (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Fererazione Nationale Ordini Professioni Infermieristche. Available online: http://www.fnopi.it/ (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Association for Health Promotion Ireland (AHPI). Available online: https://ahpi.ie/ (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Health Promotion Group, Italian Public Health Society. Available online: http://www.societaitalianaigiene.org/site/new/index.php/gdl/15-health-promotion (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Italian Society for the Promotion of Health (SiPs). Available online: http://www.sipsalute.it (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- IUHPE Health Promotion Accreditation System—National Accreditation Organisation (NAOs). Available online: https://www.iuhpe.org/index.php/en/nao (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Heath Promotion Research Centre (HPRC), National University of Ireland Galway. Available online: http://www.nuigalway.ie/researchcentres/collegeofmedicinenursingamphealthsciences/healthpromotionresearchcentre/ (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- National Center for Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Rome. Available online: https://www.iss.it/?p=41 (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Experimental Center for Health Promotion and Health Education (CeSPES), Perugia. Available online: http://cespes.unipg.it/ (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Regional Documentation Center for Health Promotion (DoRs), Piemonte. Available online: https://www.dors.it/ (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Mereu, A.; Sotgiu, A.; Buja, A.; Casuccio, A.; Cecconi, R.; Fabiani, L.; Guberti, E.; Lorini, C.; Minelli, L.; Pocetta, G.; et al. The Health Promotion Working Group of the Italian Society of Hygiene, Preventive Medicine and Public Health (SItI). Health Promotion and public health: What is common and what is specific? Review of the European debate and perspectives for professional development. Epidemiol. Prev. 2015, 39 (Suppl. 1), 33–38. Available online: http://www.epiprev.it/materiali/2015/EP2015_I4S1_033.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2019). [PubMed]

- Barbera, E.; Coffano, M.E.; Contu, P.; Fiorini, C.; Pocetta, G.; Prezza, M.; Scarponi, S.; Sotgiu, A.; Tortone, C. I Manuali Del Progetto CompHP; IUHPE: Paris, France, 2014; Available online: https://www.dors.it/documentazione/testo/201405/CompHP_Handbooks_ITA.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2019).

| Ireland | Italy | |

|---|---|---|

| Policy context | ● Strategic framework: Healthy Ireland [35] Vision: A Healthy Ireland, where everyone can enjoy physical and mental health and wellbeing to their full potential. ● Minister for Health Promotion and the National Drugs Strategy | ● Strategic framework: Guadagnare Salute—Rendere facili le scelte salutari [36] integrated into National and Regional Prevention Plans. Primary objective: to prevent and change unhealthy conducts that are the main risk factors for major non-communicable diseases |

| Implementation of Health Promotion | ● Health and Wellbeing Division (HSE) [37] ● NGOs with remit for Health Promotion (e.g., [38,39,40]) the private sector | ● Some evidence of implementation at national/regional level |

| Specialized Health Promotion workforce | ● Specialized Health Promotion workforce circa 250 across the HSE, NGOs and private sector | ● Very limited Health Promotion specific workforce/no specific career path |

| Health Promotion Academic Education | ● Three courses accredited by the IUHPE (two undergraduate/one postgraduate) [41] ● Two other Health Promotion specific courses [42,43] | ● Two courses accredited by the IUHPE (one undergraduate/one postgraduate [41] ● One course specific to Health Promotion) ● In 2019, the Ministry of University and Research included Health Promotion as a topic for post graduate courses for 22 non-medical health professions at national level [44] |

| National Professional Associations | ● Association for Health Promotion Ireland (AHPI) [45] | ● Health Promotion Group in Public Health Society [46] ● Italian Society for the Promotion of Health (SiPs) [47] |

| National Accreditation Organization (NAO) [48] | ● NAO (Established 2016) ● Individual practitioners registered by Irish NAO | ● Work ongoing on developing NAO ● Individual practitioners registered at IUHPE global level |

| Professional status | ● No current statutory recognition of Health Promotion but interest in this for the future ● Voluntary registration (Irish NAO) ● Practitioners currently not required to be on any professional statutory register to be employed in Health Promotion | ● No current statutory recognition of Health Promotion and unlikely to be in future ● Voluntary registration (IUHPE Global) ● Practitioners usually required to be on statutory register in relevant profession (e.g., medicine/psychology) to be employed in Health Promotion |

| Other dedicated Health Promotion organizations | Research ● Health Promotion Research Centre, NUIG [49] | Policy, research and evaluation ● National Center for Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [50] Research, education and training ● Experimental Center for Health Promotion and Health Education—CeSPES [51] Knowledge transfer and training ● Regional Documentation Center for Health Promotion—DoRs [52] |

| Ireland | Italy | |

|---|---|---|

| Health Promotion Education | Academic courses enhanced in terms of: ○ Development ○ Quality/ethos ○ Recruitment ○ Marketability Enhanced: ○ Students’ learning ○ Lecturers’ credibility ○ Graduates sense of Health Promotion role | Academic/training courses enhanced in terms of: ○ Development ○ Quality ○ Marketability Enhanced: ○ Students’ learning ○ Graduates’ knowledge/confidence |

| Health Promotion Profession | Profession ○ Strengthened recognition of profession NAO ○ Basis for NAO development and growth Professional Association ○ Helped consolidate, refocus organization ○ Helped ’sell’ Health Promotion to decision-makers/employers Workforce/practitioners ○ Engendered sense of professional community | NAO ○ Basis for developing NAO Workforce/practitioners ○ Supported recognition of Health Promotion roles (health professionals) ○ Basis for research resulting in changes in Health Promotion workforce. |

| Health Promotion Practice | Quality assurance ○ Used as structure/clear pathway for good practice ○ Facilitated holistic focus on Health Promotion ○ Provided clarity of role for workforce ○ Ensured all using the same language. | Quality assurance ○ Provided guide/checklist for good practice ○ Clarified Health Promotion roles ○ Supported reflection. ○ Informed planning at regional level. |

| Ireland | Italy | |

|---|---|---|

| Key requirement | Knowledge and deep understanding of the competencies | Knowledge and understanding of Health Promotion |

| Practical advice | ● Reflect on what is already being done and link the competencies to that - it’s less threatening ● Get buy-in from the wider workforce ● CompHP Handbooks/IUHPE website are key resources ● Gather peers and brainstorm what implementation will look like | ● Link implementation to other relevant developments ● Ensure implementation is a bottom-up process ● Select examples of best practice in implementation and share with decision-makers ● Talk to those who have already implemented them ● Create enthusiasm |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Battel-Kirk, B.; Barry, M.M. Implementation of Health Promotion Competencies in Ireland and Italy—A Case Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4992. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244992

Battel-Kirk B, Barry MM. Implementation of Health Promotion Competencies in Ireland and Italy—A Case Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(24):4992. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244992

Chicago/Turabian StyleBattel-Kirk, Barbara, and Margaret M. Barry. 2019. "Implementation of Health Promotion Competencies in Ireland and Italy—A Case Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 24: 4992. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244992

APA StyleBattel-Kirk, B., & Barry, M. M. (2019). Implementation of Health Promotion Competencies in Ireland and Italy—A Case Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 4992. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244992