Perfectly Active Teenagers. When Does Physical Exercise Help Psychological Well-Being in Adolescents?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurement Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

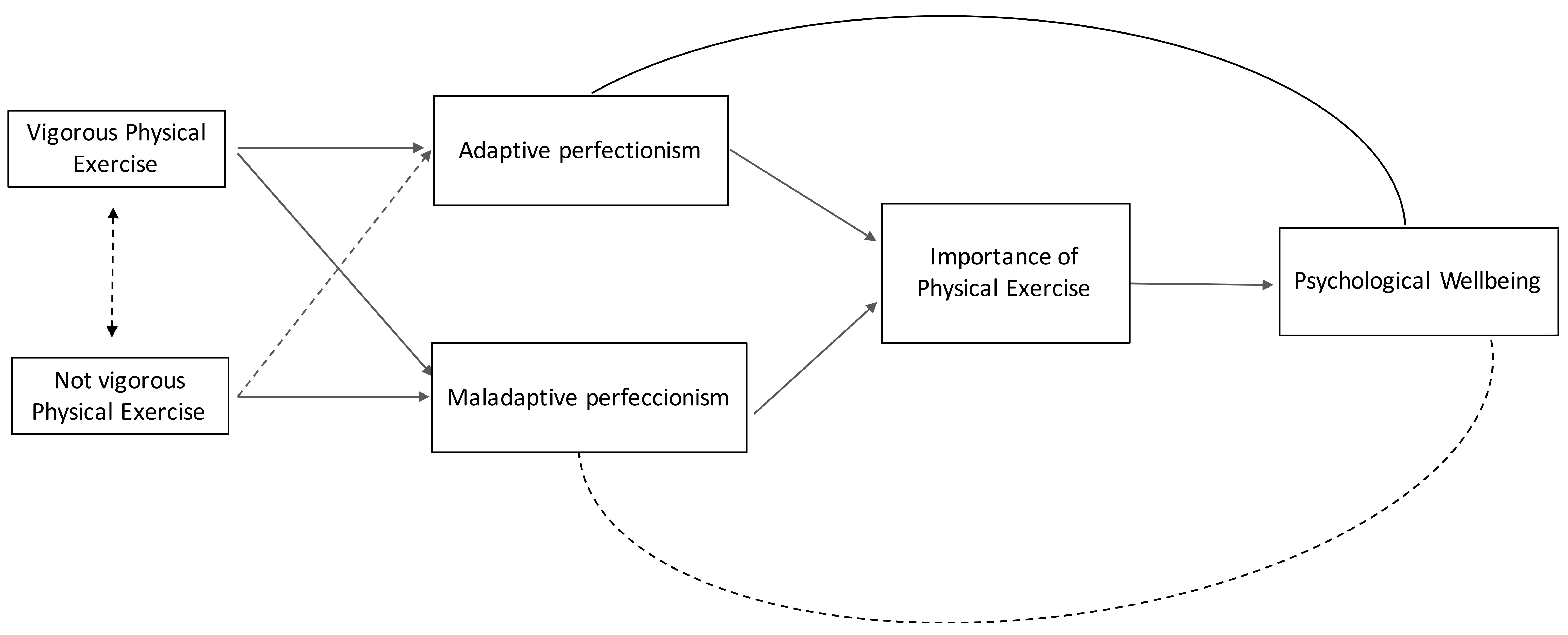

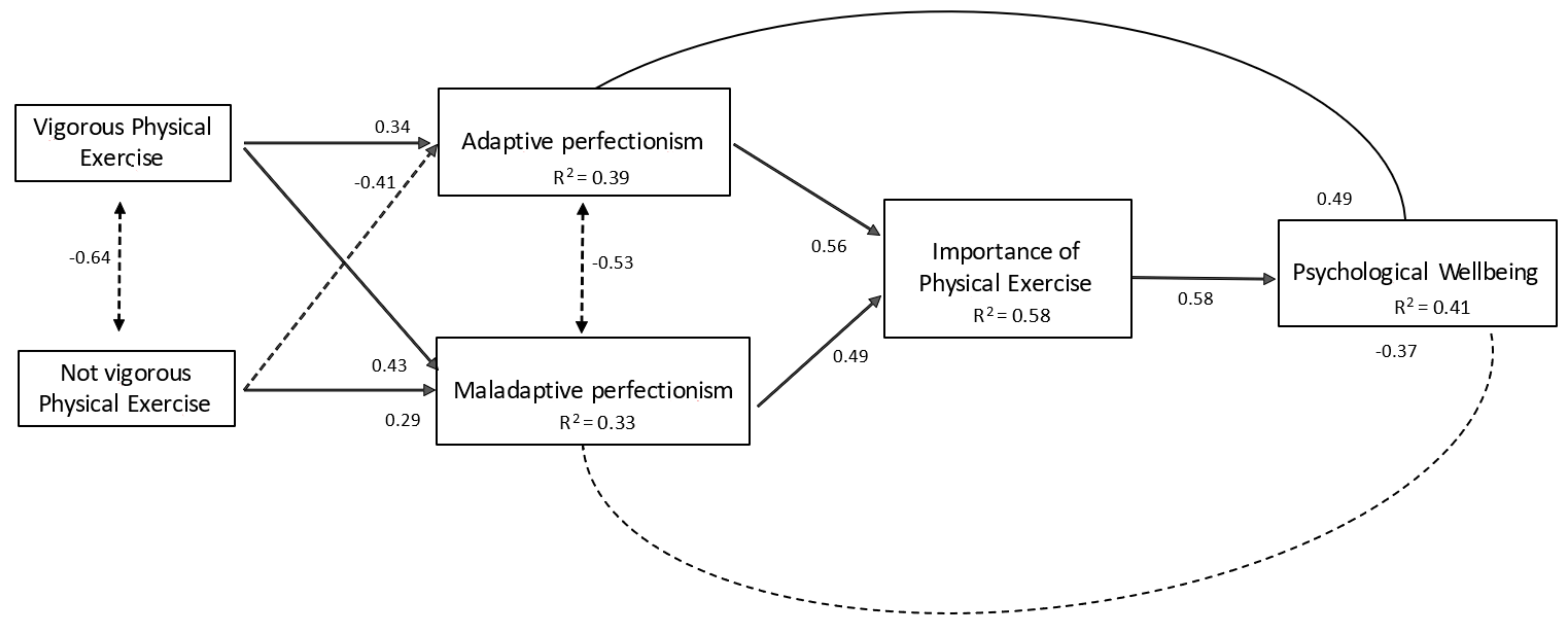

Hypothesized Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crocetti, E. Identity formation in adolescence: The dynamic of forming and consolidating identity commitments. Child. Dev. Perspect. 2017, 11, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardouly, J.; Holland, E. Social media is not real life: The effect of attaching disclaimer-type labels to idealized social media images on women’s body image and mood. N. Media Soc. 2018, 20, 4311–4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukachinsky, R.; Dorros, S.M. Parasocial romantic relationships, romantic beliefs, and relationship outcomes in USA adolescents: Rehearsing love or setting oneself up to fail? J. Child. Media 2018, 12, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, J. Teenage pregnancy and mental health. Societies 2016, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, M.L.D.; Gutierrez, B.C.; Bryant, D.N.; Arredondo, M.; Takesako, K. Gender is what you look like: Emerging gender identities in young children and preoccupation with appearance. Self Identity 2018, 17, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agans, J.P.; Ettekal, A.V.; Erickson, K.; Lerner, R.M. Positive youth development through sport: A relational developmental systems approach. In Positive Youth Development through Sport; Holt, N.L., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, E.; Benish-Weisman, M. Value development during adolescence: Dimensions of change and stability. J. Pers. 2018, 87, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braams, B.R.; van Duijvenvoorde, A.C.; Peper, J.S.; Crone, E.A. Longitudinal changes in adolescent risk-taking: A comprehensive study of neural responses to rewards, pubertal development, and risk-taking behavior. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 7226–7238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirois, F. Perfectionism and health behaviors: A self-regulation resource perspective. In Perfectionism, Health, and Well-Being; Sirois, F., Molnar, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Hernández, J.; Gómez-López, M.; Alarcón-García, A.; Muñoz-Villena, A.J. Perfectionism and stress control in adolescents: Differences and relations according to the intensity of sports practice. JHSE 2019, 14, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luszczynska, A.; Zarychta, K.; Horodyska, K.; Liszewska, N.; Gancarczyk, A.; Czekierda, K. Functional perfectionism and healthy behaviors: The longitudinal relationships between the dimensions of perfectionism, nutrition behavior, and physical activity moderated by gender. Curr. Issues Personal. Psychol. 2015, 3, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushing, C.C.; Bejarano, C.M.; Mitchell, T.B.; Noser, A.E.; Crick, C.J. Individual differences in negative affectivity and physical activity in adolescents: An ecological momentary assessment study. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 2772–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubans, D.; Richards, J.; Hillman, C.; Faulkner, G.; Beauchamp, M.; Nilsson, M.; Biddle, S. Physical activity for cognitive and mental health in youth: A systematic review of mechanisms. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, S.; Kalak, N.; Gerber, M.; Clough, P.J.; Lemola, S.; Sadeghi Bahmani, D.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E. During early to mid-adolescence, moderate to vigorous physical activity is associated with restoring sleep, psychological functioning, mental toughness and male gender. J. Sport Sci. 2017, 35, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-López, M.; Granero-Gallegos, A.; Isorna Folgar, M. Analysis of psychological factors that affect high athletic performance in kayakers. Rev. Iberoam. Diagn. Eval. 2013, 1, 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, M.; Lindwall, M.; Brand, S.; Lang, C.; Elliot, C.; Pühse, U. Longitudinal relationships between perceived stress, exercise self-regulation and exercise involvement among physically active adolescents. J. Sport Sci. 2015, 33, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, C.; Brand, S.; Colledge, F.; Ludyga, S.; Pühse, U.; Gerber, M. Adolescents’ personal beliefs about sufficient physical activity are more closely related to sleep and psychological functioning than self-reported physical activity: A prospective study. J. Sport Health Sci. 2018, 8, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkley, T.; Teychenne, M.; Downing, K.L.; Ball, K.; Salmon, J.; Hesketh, K.D. Early childhood physical activity, sedentary behaviors and psychosocial Well-being: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2014, 62, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.; Marques, A.; Sarmento, H.; Carreiro da Costa, F. Adolescents’ perspectives on the barriers and facilitators of physical activity: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Health Educ. Res. 2015, 30, 742–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, G.C.; Sawyer, S.M.; Santelli, J.S.; Ross, D.A.; Afifi, R.; Allen, N.B.; Kakuma, R. Our future: A Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2423–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancassiani, F.; Pintus, E.; Holte, A.; Paulus, P.; Moro, M.F.; Cossu, G.; Lindert, J. Enhancing the emotional and social skills of the youth to promote their wellbeing and positive development: A systematic review of universal school-based randomized controlled trials. CPEMH 2015, 11 (Suppl. S1 M2), 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suetani, S.; Mamun, A.; Williams, G.M.; Najman, J.M.; McGrath, J.J.; Scott, J.G. Longitudinal association between physical activity engagement during adolescence and mental health outcomes in young adults: A 21-year birth cohort study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2017, 94, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickhouser, J.E.; Zell, E.; Krizan, Z. Does personality predict health and well-being? A metasynthesis. Health Psychol. 2017, 36, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, S.T.; Baharudin, R. The relationship between adolescents’ perceived parental involvement, self-efficacy beliefs, and subjective well-being: A multiple mediator model. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 126, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, E. Self-oriented perfectionism and self-assessment as predictors of adolescents’ subjective well-being. Educ. Res. Rev. 2014, 9, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, F.; Craddock, A.E. How attempts to meet others’ unrealistic expectations affect health: Health-promoting behaviours as a mediator between perfectionism and physical health. Psychol. Health Med. 2016, 21, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jowett, G.E.; Hill, A.P.; Hall, H.K.; Curran, T. Perfectionism, burnout and engagement in youth sport: The mediating role of basic psychological needs. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2016, 24, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, S.L.; Milyavskaya, M. Domain-specific perfectionism: An examination of perfectionism beyond the trait-level and its link to well-being. J. Res. Pers. 2018, 74, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadra-Martínez, D.; Georgudis-Mendoza, C.N.; Alfaro-Rivera, R.A. The social representation of sport and physical education by students with obesity. Rev. Latinoam. Cienc. Soc. Niñez Juv. 2012, 10, 983–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Vink, K.; Raudsepp, L. Perfectionistic strivings, motivation and engagement in sport-specific activities among adolescent team athletes. Percept. Motor Skill 2018, 125, 596–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Hernández, J.; Muñoz-Villena, A.J. Perfectionism and sporting practice. Functional stress regulation in adolescence. Ann. Psicol. 2019, 35, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, S.J.; Wade, T.D.; Shafran, R. Perfectionism as a transdiagnostic process: A clinical review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D.J.; Stoeber, J.; Passfield, L. Motivation mediates the perfectionism–burnout relationship: A three-wave longitudinal study with junior athletes. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2016, 38, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.J.; Jeong, D.Y. Psychological Well-being, life satisfaction, and self-esteem among adaptive perfectionists, maladaptive perfectionists, and nonperfectionists. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 72, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.P.; Mallinson-Howard, S.H.; Jowett, G.E. Multidimensional perfectionism in sport: A meta-analytical review. Sport Exerc. Perform. 2018, 7, 235–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodewyk, K.R. Associations between trait personality, anxiety, self-efficacy and intentions to exercise by gender in high school physical education. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 38, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longbottom, J.L.; Grove, J.R.; Dimmock, J.A. An examination of perfectionism traits and physical activity motivation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2010, 11, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternfeld, B.; Colvin, A.; Stewart, A.; Dugan, S.; Nackers, L.; El Khoudary, S.R.; Karvonen-Gutierrez, C. The impact of a healthy lifestyle on future physical functioning in midlife women. Med. Sci. Sport Exerc. 2017, 49, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotwals, J.K.; Stoeber, J.; Dunn, J.G.H.; Stoll, O. Are perfectionistic strivings in sport adaptive? A systematic review of confirmatory, contradictory, and mixed evidence. Can. Psychol. 2012, 53, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudreau, P.; Verner-Filion, J. Dispositional perfectionism and Well-being: A test of the 2 × 2 model of perfectionism in the sport domain. Sport Exerc. Perform. 2012, 1, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.P.; Curran, T. Multidimensional perfectionism and burnout: A meta-analysis. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 20, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.C.; Haapanen, S.; Tolvanen, A.; Robazza, C.; Duda, J.L. Predicting athletes’ functional and dysfunctional emotions: The role of the motivational climate and motivation regulations. J. Sport Sci. 2017, 35, 1598–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-García, J.; Queralt, A.; Castillo, I.; Sallis, J.F. Changes in physical activity domains during the transition out of high school: Psychosocial and environmental correlates. J. Phys. Act. Health 2015, 12, 1414–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Länsimies, H.; Pietilä, A.M.; Hietasola-Husu, S.; Kangasniemi, M. A systematic review of adolescents’ sense of coherence and health. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2017, 31, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corder, K.; Sharp, S.J.; Atkin, A.J.; Griffin, S.J.; Jones, A.P.; Ekelund, U.; van Sluijs, E.M. Change in objectively measured physical activity during the transition to adolescence. Br. J. Sport Med. 2015, 49, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Wu, L.; Ming, Q. How does physical activity intervention improve self-esteem and self-concept in children and adolescents? Evidence from a meta-analysis. PloS ONE 2015, 10, e0134804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantanista, A.; Osiński, W.; Borowiec, J.; Tomczak, M.; Król-Zielińska, M. Body image, BMI, and physical activity in girls and boys aged 14–16 years. Body Image 2015, 15, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blázquez Garcés, J.V.; Corte-Real, N.; Dias, C.; Fonseca, A.M. Sports practice and subjective Well-being: Study with Portuguese teenagers. RIPED 2009, 4, 105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, S. The Role of Perfectionism and Shame in Understanding Excessive Exercise Tendencies. Ph.D. Thesis, Laurentian University of Sudbury, Sudbury, ON, Canada, March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, A.; Belloch, A.; Perpiñá, C. The evaluation of perfectionism: Usefulness of the multidimensional scale of perfectionism in the Spanish population. Anál. Modif. Conduct. 2010, 36, 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, R.O.; Heimberg, R.G.; Holt, C.S.; Mattia, J.I.; Neubauer, A.L. A comparison of two measures of perfectionism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1993, 14, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. Scale of psychological well-being. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, D.; Rodríguez-Carvajal, R.; Blanco, A.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Gallardo, I.; Valle, C.; Dierendonck, D.V. Spanish adaptation of the Psychological Well-Being Scales (PWBS). Psicothema 2006, 18, 572–577. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dierendonck, D. The construct validity of Ryff’s Scale of Psychological Well-being and its extensión with spiritual Well-being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 36, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Sallis, J.F. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sport Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, H. Ethical Choices in Research: Managing Data, Writing Reports, and Publishing Results in the Social Sciences; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Multivariate Applications Book Series. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Marcoulides, G.A. Interaction and Nonlinear Effects in Structural Equation Modeling; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cattuzzo, M.T.; dos Santos Henrique, R.; Ré, A.H.N.; de Oliveira, I.S.; Melo, B.M.; de Sousa Moura, M.; Stodden, D. Motor competence and health related physical fitness in youth: A systematic review. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2016, 19, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Murcia, J.A.; Cervelló, E.; Huéscar, E.; Llamas, L. Relationship of motives to practice sport in adolescents with perceived competence, body image and healthy habits. Cult. Educ. 2011, 23, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-López, M.; Ruiz-Juan, F.; García Montes, M.E.; Granero-Gallegos, A.; Piéron, M. Reasons mentioned by university student who practice physical and sporting activities. Rev. Lat. Am. Psicol. 2009, 41, 519–532. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Kates, A. Can the affective response to exercise predict future motives and physical activity behavior? A systematic review of published evidence. Ann. Behav. Med. 2015, 49, 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goguen-Carpenter, J.; Bélanger, M.; O’Loughlin, J.; Xhignesse, M.; Ward, S.; Caissie, I.; Sabiston, C. Association between physical activity motives and type of physical activity in children. IJSEP 2017, 15, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, A.M.; Evjen, E. Gender differences in motives for participation in sports and exercise among Norwegian adolescents. BJHPA 2018, 10, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, G.; Kljajic, K.; Franche, V.; Gaudreau, P. The 2 × 2 model of perfectionism: Assumptions, trends, and potential developments. In The Psychology of Perfectionism; Stoeber, J., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 58–81. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, S.; Coppolino, P.; Oliva, P. Exercise dependence and maladaptive perfectionism: The mediating role of basic psychological needs. Int. J. Ment. Health Adict. 2016, 14, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D.J.; Stoeber, J.; Passfield, L. Perfectionism and training distress in junior athletes: A longitudinal investigation. J. Sport Sci. 2017, 35, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gucciardi, D.; Mahoney, J.; Jalleh, G.; Donovan, R.; Parkes, J. Perfectionistic profiles among elite athletes and differences in their motivational orientations. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2012, 34, 159–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenvinge, J.H.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Pettersen, G.; Martinsen, M.; Stornæs, A.V.; Pensgaard, A.M. Are adolescent elite athletes less psychologically distressed than controls? A cross-sectional study of 966 Norwegian adolescents. Open Access J. Sports Med. 2018, 9, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, E.M.; Corcoran, P.; O’Regan, G.; Keeley, H.; Cannon, M.; Carli, V.; Balazs, J. Physical activity in European adolescents and associations with anxiety, depression and Well-being. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 2017, 26, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, J.; Brown, A. A qualitative study of ‘fear’ as a regulator of children’s independent physical activity in the suburbs. Health Place 2013, 24, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, T.; Zahner, L.; Pühse, U.; Schneider, S.; Puder, J.J.; Kriemler, S. Physical activity, bodyweight, health and fear of negative evaluation in primary school children. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sport 2010, 20, e27–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, S.J.H.; Mutrie, N. Psychology of Physical Activity: Determinants, Well-Being and Interventions; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, A.P.; Robson, S.J.; Stamp, G.M. The predictive ability of perfectionistic traits and self-presentational styles in relation to exercise dependence. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 86, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n = 436 Age = 16.80 Years Old (SD = 2.93) “I Practice Physical Exercise for…”: | Range | M(SD) | Kurtosis | Asymmetry |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| To reduce weight | 0–6 | 2.74 (1.84) | 1.32 | 0.26 |

| To feel active | 0–6 | 4.03 (0.92) | 1.43 | 1.74 |

| To improve quality of life | 0–6 | 2.95 (1.93) | 0.36 | 0.07 |

| To be strong and vigorous | 0–6 | 3.71 (1.64) | 1.04 | 1.30 |

| To improve mood | 0–6 | 2.38 (1.22) | 0.83 | 1.33 |

| Variables | Vigorous (n = 193) M(SD) | Non Vigorous (n = 243) M(SD) | (λ) | F | CE (Sig.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Importance of Physical Exercise | |||||

| Value of the PE in general | 4.41 (1.32) | 2.89 (1.74) | 0.74 | 7.26 | 5.29 ** |

| Commitment to the PE | 4.63 (1.46) | 2.57 (1.23) | 0.62 | 3.81 | 3.53 * |

| Effort for the PE | 3.94 (1.05) | 2.37 (1.34) | 0.81 | 8.93 | 4.90 ** |

| Importance of the PE | 4.32 (1.27) | 2.61 (1.44) | 0.69 | 6.04 | 4.68 * |

| Perfectionism | |||||

| Adaptive perfectionism | 3.26 (1.38) | 3.13 (1.07) | |||

| Maladaptive perfectionism | 3.82 (0.93) | 2.76 (1.04) | 0.92 | 8.53 | 4.34 * |

| Psychological Well-Being | |||||

| Psychological Well-being | 4.39 (1.35) | 2.86 (0.67) | 0.87 | 6.95 | 8.03 ** |

| Variables | M | SD | Range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Importance of physical exercise | 3.14 | 0.76 | 0–6 | - | 0.53 **(0.00) | 0.48 *(0.01) | 0.56 **(0.00) |

| Adaptive perfectionism | 2.94 | 1.07 | 1–5 | - | 0.37 **(0.00) | 0.67 **(0.00) | |

| Maladaptive perfectionism | 3.02 | 0.84 | 1–5 | - | −0.49 **(0.00) | ||

| Psychological well-being | 3.78 | 1.68 | 1–6 | - |

| Model | χ2 | df | RMSEA | (90% CI) | SRMR | NNFI | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 451.35 | 154 | 0.028 | (0.014–0.032) | 0.061 | 0.925 | 0.932 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Hernández, J.; Gómez-López, M.; Pérez-Turpin, J.A.; Muñoz-Villena, A.J.; Andreu-Cabrera, E. Perfectly Active Teenagers. When Does Physical Exercise Help Psychological Well-Being in Adolescents? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4525. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224525

González-Hernández J, Gómez-López M, Pérez-Turpin JA, Muñoz-Villena AJ, Andreu-Cabrera E. Perfectly Active Teenagers. When Does Physical Exercise Help Psychological Well-Being in Adolescents? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(22):4525. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224525

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Hernández, Juan, Manuel Gómez-López, José Antonio Pérez-Turpin, Antonio Jesús Muñoz-Villena, and Eliseo Andreu-Cabrera. 2019. "Perfectly Active Teenagers. When Does Physical Exercise Help Psychological Well-Being in Adolescents?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 22: 4525. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224525

APA StyleGonzález-Hernández, J., Gómez-López, M., Pérez-Turpin, J. A., Muñoz-Villena, A. J., & Andreu-Cabrera, E. (2019). Perfectly Active Teenagers. When Does Physical Exercise Help Psychological Well-Being in Adolescents? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(22), 4525. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224525