Previous Use of Mammography as a Proxy for General Health Checks in Association with Better Outcomes after Major Surgeries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Source of Data

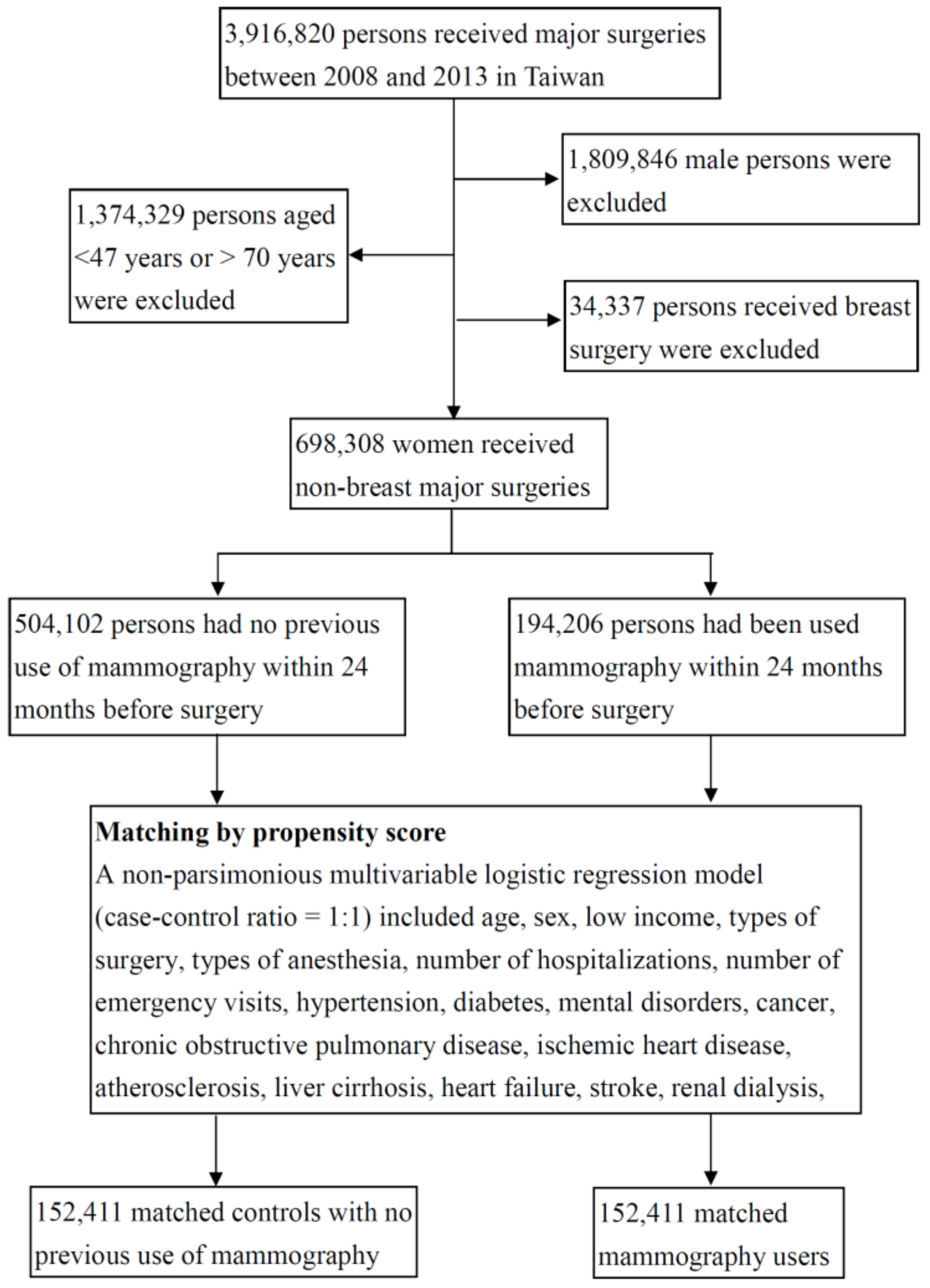

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Measures and Definitions

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ICD-9-CM | International Code of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification |

| OR | odds ratio |

| CI | confidence interval |

References

- Weiser, T.G.; Haynes, A.B.; Molina, G.; Lipsitz, S.R.; Esquivel, M.M.; Uribe-Leitz, T.; Fu, R.; Azad, T.; Chao, T.E.; Berry, W.R.; et al. Size and distribution of the global volume of surgery in 2012. Bull. World Health Organ. 2016, 94, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhry, N.K.; Fletcher, R.H.; Soumerai, S.B. Systematic review: The relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005, 142, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkmeyer, J.D.; Siewers, A.E.; Finlayson, E.V.; Stukel, T.A.; Lucas, F.L.; Batista, I.; Welch, H.G.; Wennberg, D.E. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 1128–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, N.N.; Hatcher, J.; Chaturvedi, N.; Jafar, T.H. Effect of general practitioner education on adherence to antihypertensive drugs: Cluster randomised controlled trial. Br. Med. J. 2007, 335, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, S.; Moss, J.R.; Sullivan, T.R.; Newton, S.S.; Stocks, N.P. Effectiveness of general practice-based health checks: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2014, 64, e47–e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulware, L.E.; Marinopoulos, S.; Phillips, K.A.; Hwang, C.W.; Maynor, K.; Merenstein, D.; Wilson, R.F.; Barnes, G.J.; Bass, E.B.; Powe, N.R.; et al. Systematic review: The value of the periodic health evaluation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 146, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.H.; Chiu, Y.H.; Luh, D.L.; Yen, M.F.; Wu, H.M.; Chen, L.S.; Tung, T.H.; Huang, C.C.; Chan, C.C.; Shiu, M.N.; et al. Community-based multiple screening model: Design, implementation, and analysis of 42,387 participants. Cancer 2004, 100, 1734–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, A.M.; Tsau, H.S.; Fann, J.C.; Chen, S.L.; Chiu, S.Y.; Lee, Y.C.; Pan, S.L.; Chiu, H.M.; Kuo, W.H.; Chang, K.J.; et al. Population-based breast cancer screening with risk-based and universal mammography screening compared with clinical breast examination: A propensity score analysis of 1429890 Taiwanese women. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.C.; Shen, W.W.; Chang, C.C.; Chang, H.; Chen, T.L. Surgical adverse outcomes in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based study. Ann. Surg. 2013, 257, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, C.C.; Liao, C.C.; Chang, Y.C.; Jeng, L.B.; Yang, H.R.; Shih, C.C.; Chen, T.L. Adverse outcomes after noncardiac surgery in patients with diabetes: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 3216–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.; Saunders, C.L.; Harte, E.; Griffin, S.J.; MacLure, C.; Mant, J.; Meads, C.; Walter, F.M.; Usher-Smith, J.A. Delivery and impact of the NHS Health Check in the first 8 years: A systematic review. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 68, e449–e459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forster, A.S.; Burgess, C.; Dodhia, H.; Fuller, F.; Miller, J.; McDermott, L.; Gulliford, M.C. Do health checks improve risk factor detection in primary care? Matched cohort study using electronic health records. J. Public Health 2016, 38, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krogsbøll, L.T.; Jørgensen, K.J.; Grønhøj Larsen, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C. General health checks in adults for reducing morbidity and mortality from disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. Med. J. 2012, 345, e7191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, H.M.; Chen, S.L.; Yen, A.M.; Chiu, S.Y.; Fann, J.C.; Lee, Y.C.; Pan, S.L.; Wu, M.S.; Liao, C.S.; Chen, H.H.; et al. Effectiveness of fecal immunochemical testing in reducing colorectal cancer mortality from the One Million Taiwanese Screening Program. Cancer 2015, 121, 3221–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, Y.P.; Hu, T.H.; Cho, P.Y.; Chen, H.H.; Yen, A.M.; Chen, S.L.; Chiu, S.Y.; Fann, J.C.; Su, W.W.; Fang, Y.J.; et al. Evaluation of abdominal ultrasonography mass screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Hepatology 2014, 59, 1840–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, R.D. How important is peri-operative hypertension? Anaesthesia 2014, 69, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noordzij, P.G.; Boersma, E.; Schreiner, F.; Kertai, M.D.; Feringa, H.H.; Dunkelgrun, M.; Bax, J.J.; Klein, J.; Poldermans, D. Increased preoperative glucose levels are associated with perioperative mortality in patients undergoing noncardiac, nonvascular surgery. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2007, 156, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafsson, U.O.; Thorell, A.; Soop, M.; Ljungqvist, O.; Nygren, J. Haemoglobin A1c as a predictor of postoperative hyperglycaemia and complications after major colorectal surgery. Br. J. Surg. 2009, 96, 1358–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh, R.F.; Moghadamyeghaneh, Z.; Whealon, M.D.; Hanna, M.H.; Mills, S.D.; Pigazzi, A.; Stamos, M.J.; Carmichael, J.C. Body mass index significantly impacts outcomes of colorectal surgery. Am. Surg. 2016, 82, 930–935. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Davis, T.C.; Arnold, C.; Berkel, H.J.; Nandy, I.; Jackson, R.H.; Glass, J. Knowledge and attitude on screening mammography among low-literate, low-income women. Cancer 1996, 78, 1912–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.P.; Brownlee, C.D.; McCoy, T.P.; Pignone, M.P. The effect of health literacy on knowledge and receipt of colorectal cancer screening: A survey study. BMC. Fam. Pract. 2007, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.Y.; Tsai, T.I.; Tsai, Y.W.; Kuo, K.N. Health literacy, health status, and healthcare utilization of Taiwanese adults: Results from a national survey. BMC. Public Health 2010, 10, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewalt, D.A.; Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.; Lohr, K.N.; Pignone, M.P. Literacy and health outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2004, 19, 1228–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghannadi, S.; Amouzegar, A.; Amiri, P.; Karbalaeifar, R.; Tahmasebinejad, Z.; Kazempour-Ardebili, S. Evaluating the effect of knowledge, attitude, and practice on self-management in Type 2 diabetic patients on dialysis. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 2016, 3730875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muir, K.W.; Ventura, A.; Stinnett, S.S.; Enfiedjian, A.; Allingham, R.R.; Lee, P.P. The influence of health literacy level on an educational intervention to improve glaucoma medication adherence. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 87, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, L.F.; Pedersen, A.F.; Andersen, B.; Vedsted, P. Social support and non-participation in breast cancer screening: A Danish cohort study. J. Public Health 2016, 38, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberger, P.H.; Jokl, P.; Ickovics, J. Psychosocial factors and surgical outcomes: An evidence-based literature review. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2006, 14, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxman, T.E.; Freeman, D.H.; Manheimer, E.D. Lack of social participation or religious strength and comfort as risk factors for death after cardiac surgery in the elderly. Psychosom. Med. 1995, 57, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contrada, R.J.; Goyal, T.M.; Cather, C.; Rafalson, L.; Idler, E.L.; Krause, T.J. Psychosocial factors in outcomes of heart surgery: The impact of religious involvement and depressive symptoms. Health Psychol. 2004, 23, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallant, M.P. The influence of social support on chronic illness self-management: A review and directions for research. Health Educ. Behav. 2003, 30, 170–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peek, M.E.; Han, J.H. Disparities in screening mammography. Current status, interventions and implications. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2004, 19, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, M.B.; Moore, S.; Shtatland, E.; Bright, R. The relation of household income to mammography utilization in a prepaid health care system. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Birkmeyer, N.J.; Gu, N.; Baser, O.; Morris, A.M.; Birkmeyer, J.D. Socioeconomic status and surgical mortality in the elderly. Med. Care 2008, 46, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ultee, K.H.J.; Tjeertes, E.K.M.; Bastos Gonçalves, F.; Rouwet, E.V.; Hoofwijk, A.G.M.; Stolker, R.J.; Verhagen, H.J.M.; Hoeks, S.E. The relation between household income and surgical outcome in the Dutch setting of equal access to and provision of healthcare. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Use of Mammography | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 152,411) | Yes (n = 152,411) | ||||

| Age, years | n | (%) | n | (%) | 1.0000 |

| 47–49 | 17,450 | (11.5) | 17,450 | (11.5) | |

| 50–54 | 38,469 | (25.2) | 38,469 | (25.2) | |

| 55–59 | 37,676 | (24.7) | 37,676 | (24.7) | |

| 60–64 | 32,143 | (21.1) | 32,143 | (21.1) | |

| 65–70 | 26,673 | (17.5) | 26,673 | (17.5) | |

| Low income | 1.0000 | ||||

| No | 15,1396 | (99.3) | 15,1396 | (99.3) | |

| Yes | 1015 | (0.7) | 1015 | (0.7) | |

| Number of hospitalizations | 1.0000 | ||||

| 0 | 12,2469 | (80.4) | 12,2469 | (80.4) | |

| 1 | 22,834 | (15.0) | 22,834 | (15.0) | |

| 2 | 4017 | (2.6) | 4017 | (2.6) | |

| ≥3 | 3091 | (2.0) | 3091 | (2.0) | |

| Number of emergency visits | 1.0000 | ||||

| 0 | 108,688 | (71.3) | 108,688 | (71.3) | |

| 1 | 30,014 | (19.7) | 30,014 | (19.7) | |

| 2 | 8579 | (5.6) | 8579 | (5.6) | |

| ≥3 | 5130 | (3.4) | 5130 | (3.4) | |

| Types of surgery | 1.0000 | ||||

| Musculoskeletal | 52,827 | (34.7) | 52,827 | (34.7) | |

| Digestive | 24,466 | (16.1) | 24,466 | (16.1) | |

| Neurosurgery | 19,619 | (12.9) | 19,619 | (12.9) | |

| Kidney, ureter, bladder | 9539 | (6.3) | 9539 | (6.3) | |

| Respiratory | 5462 | (3.6) | 5462 | (3.6) | |

| Cardiovascular | 2620 | (1.7) | 2620 | (1.7) | |

| Eye | 1657 | (1.1) | 1657 | (1.1) | |

| Skin | 1494 | (1.0) | 1494 | (1.0) | |

| Delivery, cesarean section, abortion | 150 | (0.1) | 150 | (0.1) | |

| Others | 34,577 | (22.7) | 34,577 | (22.7) | |

| Types of anesthesia | 1.0000 | ||||

| General | 124,417 | (81.6) | 124,417 | (81.6) | |

| Epidural or spinal | 27,994 | (18.4) | 27,994 | (18.4) | |

| Medical conditions | |||||

| Hypertension | 40,639 | (26.7) | 40,639 | (26.7) | 1.0000 |

| Diabetes | 19,838 | (13.0) | 19,838 | (13.0) | 1.0000 |

| Mental disorders | 25,142 | (16.5) | 25,142 | (16.5) | 1.0000 |

| Cancer | 19,580 | (12.9) | 19,580 | (12.9) | 1.0000 |

| COPD | 10,318 | (6.8) | 10,318 | (6.8) | 1.0000 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 6964 | (4.6) | 6964 | (4.6) | 1.0000 |

| Atherosclerosis | 1997 | (1.3) | 1997 | (1.3) | 1.0000 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 1936 | (1.3) | 1936 | (1.3) | 1.0000 |

| Heart failure | 578 | (0.4) | 578 | (0.4) | 1.0000 |

| Stroke | 1059 | (0.7) | 1059 | (0.7) | 1.0000 |

| Renal dialysis | 684 | (0.5) | 684 | (0.5) | 1.0000 |

| Parkinson’s disease | 326 | (0.2) | 326 | (0.2) | 1.0000 |

| Postoperative Outcomes | Use of Mammography | Risk of Outcomes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 152,411) | Yes (n = 152,411) | |||||

| Events | % | Event | % | OR | (95% CI)* | |

| 30 day in-hospital mortality | 466 | 0.3 | 212 | 0.1 | 0.45 | (0.38–0.53) |

| Postoperative complications | ||||||

| Pneumonia | 1378 | 0.9 | 895 | 0.6 | 0.64 | (0.59–0.70) |

| Septicemia | 3879 | 2.6 | 2922 | 1.9 | 0.75 | (0.71–0.78) |

| Acute renal failure | 534 | 0.4 | 291 | 0.2 | 0.54 | (0.47–0.62) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 106 | 0.1 | 98 | 0.1 | 0.92 | (0.70–1.22) |

| Stroke | 2660 | 1.8 | 1542 | 1.0 | 0.56 | (0.53–0.60) |

| Urinary tract infection | 6654 | 4.4 | 6233 | 4.1 | 0.93 | (0.90–0.96) |

| Deep wound infection | 645 | 0.4 | 550 | 0.4 | 0.85 | (0.76–0.96) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 158 | 0.1 | 99 | 0.1 | 0.62 | (0.48–0.80) |

| Postoperative bleeding | 699 | 0.5 | 695 | 0.5 | 0.99 | (0.90–1.11) |

| Intensive care unit stay | 10,361 | 6.8 | 7506 | 4.9 | 0.68 | (0.66–0.70) |

| Medical expenditure, USD† | 2579 ± 3046 | 2392 ± 2627 | p < 0.0001 | |||

| Length of hospital stay, days† | 6.9 ± 8.3 | 6.0 ± 6.5 | p < 0.0001 | |||

| Factors of Stratification | Adverse Events* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stratums | Mammography | n | Events | Rate, % | OR | (95% CI)† |

| Age 47–49 years | No | 17,450 | 627 | 3.6 | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Yes | 17,450 | 504 | 2.9 | 0.80 | (0.71–0.90) | |

| Age 50–54 years | No | 38,469 | 1644 | 4.3 | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Yes | 38,469 | 1109 | 2.9 | 0.66 | (0.61–0.71) | |

| Age 55–59 years | No | 37,676 | 1819 | 4.8 | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Yes | 37,676 | 1304 | 3.5 | 0.70 | (0.65–0.75) | |

| Age 60–64 years | No | 32,143 | 1869 | 5.8 | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Yes | 32,143 | 1250 | 3.9 | 0.65 | (0.60–0.70) | |

| Age 65–70 years | No | 26,673 | 1855 | 7.0 | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Yes | 26,673 | 1233 | 4.6 | 0.64 | (0.59–0.69) | |

| 0 hospitalization | No | 122,469 | 5798 | 4.7 | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Yes | 122,469 | 3890 | 3.2 | 0.65 | (0.63–0.68) | |

| 1 hospitalization | No | 22,834 | 1302 | 5.7 | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Yes | 22,834 | 940 | 4.1 | 0.71 | (0.65–0.77) | |

| 2 hospitalization | No | 4017 | 331 | 8.2 | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Yes | 4017 | 271 | 6.8 | 0.80 | (0.68–0.95) | |

| ≥3 hospitalizations | No | 3091 | 383 | 12.4 | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Yes | 3091 | 299 | 9.7 | 0.75 | (0.63–0.88) | |

| 0 emergency visits | No | 108,688 | 5003 | 4.6 | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Yes | 108,688 | 3292 | 3.0 | 0.64 | (0.61–0.67) | |

| 1 emergency visit | No | 30,014 | 1685 | 5.6 | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Yes | 30,014 | 1237 | 4.1 | 0.72 | (0.67–0.77) | |

| 2 emergency visits | No | 8579 | 611 | 7.1 | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Yes | 8579 | 467 | 5.4 | 0.75 | (0.66–0.85) | |

| ≥3 emergency visits | No | 5130 | 515 | 10.0 | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Yes | 5130 | 404 | 7.9 | 0.76 | (0.66–0.87) | |

| 0 medical condition | No | 61,938 | 2723 | 4.4 | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Yes | 61,938 | 1720 | 2.8 | 0.62 | (0.58–0.65) | |

| 1 medical condition | No | 60,228 | 3184 | 5.3 | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Yes | 60,228 | 2266 | 3.8 | 0.69 | (0.66–0.73) | |

| 2 medical conditions | No | 23,692 | 1462 | 6.2 | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Yes | 23,692 | 1087 | 4.6 | 0.73 | (0.67–0.79) | |

| 3 medical conditions | No | 5553 | 368 | 6.6 | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Yes | 5553 | 275 | 5.0 | 0.73 | (0.62–0.85) | |

| ≥4 medical conditions | No | 1000 | 77 | 7.7 | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Yes | 1000 | 52 | 5.2 | 0.64 | (0.44–0.93) | |

| Time Period Before Surgery | Adverse Events* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Events | Rate, % | OR | (95% CI)† | |

| No use of mammography | 152,411 | 7814 | 5.1 | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Use mammography within 30 days | 13,184 | 387 | 2.9 | 0.64 | (0.57–0.71) |

| Use mammography within 60 days | 22,903 | 705 | 3.1 | 0.65 | (0.60–0.70) |

| Use mammography within 90 days | 30,556 | 961 | 3.2 | 0.65 | (0.60–0.69) |

| Use mammography within 120 days | 37,492 | 1199 | 3.2 | 0.65 | (0.61–0.69) |

| Use mammography within 365 days | 87,944 | 2977 | 3.4 | 0.65 | (0.63–0.68) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tai, Y.-H.; Chen, T.-L.; Cherng, Y.-G.; Yeh, C.-C.; Chang, C.-C.; Liao, C.-C. Previous Use of Mammography as a Proxy for General Health Checks in Association with Better Outcomes after Major Surgeries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4432. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224432

Tai Y-H, Chen T-L, Cherng Y-G, Yeh C-C, Chang C-C, Liao C-C. Previous Use of Mammography as a Proxy for General Health Checks in Association with Better Outcomes after Major Surgeries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(22):4432. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224432

Chicago/Turabian StyleTai, Ying-Hsuan, Ta-Liang Chen, Yih-Giun Cherng, Chun-Chieh Yeh, Chuen-Chau Chang, and Chien-Chang Liao. 2019. "Previous Use of Mammography as a Proxy for General Health Checks in Association with Better Outcomes after Major Surgeries" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 22: 4432. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224432

APA StyleTai, Y.-H., Chen, T.-L., Cherng, Y.-G., Yeh, C.-C., Chang, C.-C., & Liao, C.-C. (2019). Previous Use of Mammography as a Proxy for General Health Checks in Association with Better Outcomes after Major Surgeries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(22), 4432. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224432