Validation of the Malay Version of Mini-IPIP among Substance Use Disorder Patients Attending Methadone Clinics in Malaysia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

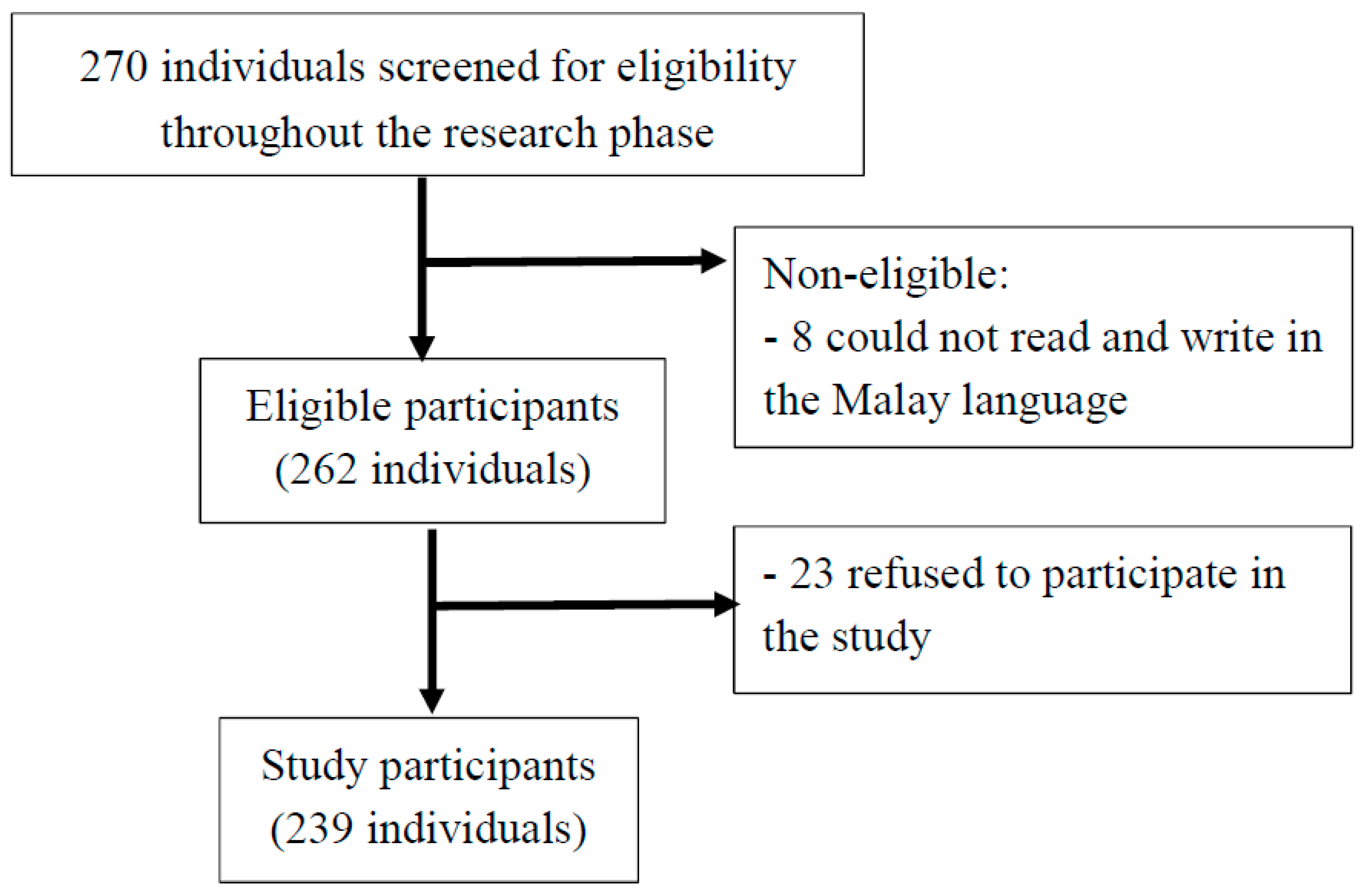

2.1. Study Design, Recruitment, and Sampling

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Materials

2.5. Translation of Mini-IPIP

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Structural Analysis for Mini-IPIP

3.2. Reliability Analysis

3.3. Concurrent Validity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013.

- Donellan, M.B.; Oswald, F.L.; Baird, B.M.; Lucas, R.E. The Mini-IPIP scales: Tiny-yet-effective measures of the Big Five factors of personality. Psychol. Assess. 2006, 18, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Block, J. A contrarian view of the five-factor approach to personality description. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 187–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, P.T., Jr.; McCrae, R.R. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) Professional Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, FL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, E.; Villar, P.; Gómez-Fraguela, J.A.; López-Romero, L. Measuring personality traits with ultra-short scales: A study of the Ten Item Personality Inventory (TIPI) in a Spanish sample. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 53, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renau, V.; Oberst, U.; Gosling, S.D.; Rusiñol, J.; Chamarro, A. Translation and validation of the Ten-Item-Personality Inventory into Spanish and Catalan. Rev. de Psicol. Ciències de I’educació I de I’esport 2013, 31, 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Baldasaro, R.E.; Shanahan, M.J.; Bauer, D.J. Psychometric properties of the Mini-IPIP in a large, nationally representative sample of young adults. J. Personal. Assess. 2013, 95, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, A.J.; Smillie, L.D.; Corr, P.J. A confirmatory factor analysis of the Mini-IPIP five-factor model personality scale. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010, 48, 688–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverdière, O.; Morin, A.J.S.; St-Hilaire, F. Factor structure and measurement invariance of a short measure of the Big Five personality traits. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2013, 55, 739–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erevik, E.K.; Pallesen, S.; Vedaa, Ø.; Andreassen, C.S.; Torsheim, T. Alcohol use among Norwegian students: Demographics, personality, and psychological health correlates of drinking patterns. Nord. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2017, 34, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erevik, E.K.; Torsheim, T.; Andreassen, C.S.; Veeda, Ø.; Pallesen, S. Recurrent cannabis use among Norwegian students: Prevalence, characteristics, and polysubstance use. Nord. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2017, 34, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotov, R.; Gamez, W.; Schmidt, F.; Watson, D. Linking “Big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 768–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grenkin, E.R.; Sher, K.J.; Wood, P.K. Personality and substance dependence symptoms: Modelling substance-specific traits. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2006, 20, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turiano, N.A.; Whiteman, S.D.; Hampson, S.E.; Roberts, B.W.; Mroczek, D.K. Personality and substance use in midlife: Conscientiousness as a moderator and the effects of trait change. J. Res. Personal. 2012, 46, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terracciano, A.; Löckenhoff, C.E.; Crum, R.M.; Bienvenu, O.J.; Costa, P.T., Jr. Five-factor Model personality profiles of drug users. BMC Psychiatry 2008, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, P.; Chen, H.; Crawford, T.N.; Brook, J.S.; Gordon, K. Personality disorders in early adolescence and the development of later substance use disorders in the general population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007, 88S, S71–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Fisher, L.A.; Elias, J.W.; Ritz, K. Predicting relapse to substance abuse as a function of personality dimensions. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1998, 22, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aluja, A.; Rossier, J.; García, L.F.; Angleitner, A.; Kuhlman, M.; Zuckerman, M. A cross-cultural shortened form of the ZKPQ (ZKPQ-50-cc) adapted to English, French, German, and Spanish languages. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 41, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, R.K.; Nadiah, S.M.S.; Geshina, A.M.S. A validity study of Malay translated Zuckerman-Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire Cross-Cultural 50 items (ZKPQ-50-CC). Health Environ. J. 2013, 4, 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Management of Substance Abuse: Process of Translation and Adaptation of Instruments. Available online: https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/ (accessed on 24 October 2016).

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelling, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Digman, J.M. Higher-order factors of the Big Five. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 1246–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Lüdtke, O.; Muthén, B.; Asparouhov, T.; Morin, A.J.; Trautwein, U.; Nagengast, B. A new look at the big five factor structure through exploratory structural equation modelling. Psychol. Assess. 2010, 22, 471–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinton, P.R.; Brownlow, C.; McMurray, I.; Cozens, B. SPSS Explained; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Guenole, N.; Chernyshenko, O.S. The suitability of Goldberg’s Big Five IPIP personality markers in New Zealand: A dimensionality, bias, and criterion validity evaluation. N. Z. J. Psychol. 2005, 34, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, B.C.; Ployhart, R.E. Assessing the convergent and discriminant validity of Goldberg’s international personality item pool: A multitrait-multimethod examination. Organ. Res. Methods 2006, 9, 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, C.J.; Donnellan, M.B. How should the internal structure of personality inventories be evaluated? Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 14, 332–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosling, S.D.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Swann, W.B., Jr. A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. J. Res. Personal. 2003, 37, 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorkapić, S.T. Ten Item Personality Inventory: A Validation Study on a Croatian Adult Sample. Eur. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 4, 192–202. Available online: http://bib.irb.hr/datoteka/866855.TIPIvalidation20-iccsbs_3453_Full_text.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2017).

- Donellan, M.B.; Lucas, R.E. Age differences in the Big Five across the life span: Evidence from two national samples. Psychol. Aging 2008, 23, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, P.T.; Terracciano, A.; McCrae, R.R. Gender differences in personality traits across cultures: Robust and surprising findings. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, R.E.; Donellan, M.B. Age differences in personality: Evidence from a nationally representative Australian sample. Dev. Psychol. 2009, 45, 1353–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sociodemographic Particulars | Mean (SD) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Male | 39.0 (0.61) | |

| Female | 35.8 (2.70) | |

| Salary | 1020.9 (662.15) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 229 (95.8) | |

| Female | 10 (4.2) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 115 (48.1) | |

| Married | 92 (38.5) | |

| Separated/divorced | 32 (13.4) | |

| Race | ||

| Malay | 219 (91.6) | |

| Chinese | 5 (2.1) | |

| Indian | 15 (6.3) | |

| Others | 0 (0) | |

| Occupational status | ||

| Full time | 147 (61.5) | |

| Part-time | 63 (26.4) | |

| Retired | 5 (2.1) | |

| Never worked/unemployed/Housewife | 24 (10.0) | |

| Educational level | ||

| Never been to school | 0 (0) | |

| Primary level | 11 (4.6) | |

| Secondary level | 204 (85.4) | |

| Tertiary level | 15 (6.3) | |

| Others | 9 (3.8) |

| Fit Indices | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Models Tested | CFI/TLI | RMSEA (90% CI) | SRMR |

| (a) 5 Factor | |||

| Initial model | 0.013/−0.137 | 0.141 (0.133–0.150) | 0.232 |

| Last model | 0.600/0.472 | 0.102 (0.088–0.116) | 0.132 |

| (b) 3-Factor | |||

| Initial model | 0.358/0.283 | 0.112 (0.104–0.121) | 0.253 |

| Last model | 0.285/0.116 | 0.136 (0.125–0.148) | 0.27 |

| (c) 2-Factor | |||

| Initial model | 0.478/0.414 | 0.101 (0.093–0.111) | 0.117 |

| Last model | 0.873/0.829 | 0.075 (0.055–0.094) | 0.064 |

| (d) Aggregate score of 5 factors | |||

| Initial model | 0.634/0.267 | 0.197 (0.150–0.248) | 0.074 |

| Last model | 0.949/0.831 | 0.094 (0.030–0.166) | 0.044 |

| Mini-IPIP | ZKPQ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity | Impulsive-Sensation-Seeking | Sociability | Aggression-Hostility | Neuroticism-Anxiety | |

| Intellect/Imagination | 0.175 ** | −0.201 ** | 0.283 ** | −0.236 ** | −0.314 ** |

| Conscientiousness | 0.295 ** | −0.308 ** | 0.428 ** | −0.412 ** | −0.391 ** |

| Extraversion | 0.290 ** | −0.075 | 0.423 ** | −0.147 ** | −0.209 ** |

| Agreeableness | 0.125 | −0.054 | 0.210 ** | −0.118 | −0.085 |

| Neuroticism | −0.150 * | 0.174 ** | −0.292 ** | 0.215 ** | 0.332 ** |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leong, F.W.; Mohd Yasin, M.A.; Muhd Ramli, E.R.; Fadzil, N.A.; Kueh, Y.C. Validation of the Malay Version of Mini-IPIP among Substance Use Disorder Patients Attending Methadone Clinics in Malaysia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4434. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224434

Leong FW, Mohd Yasin MA, Muhd Ramli ER, Fadzil NA, Kueh YC. Validation of the Malay Version of Mini-IPIP among Substance Use Disorder Patients Attending Methadone Clinics in Malaysia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(22):4434. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224434

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeong, Foo Weng, Mohd Azhar Mohd Yasin, Eni Rahaiza Muhd Ramli, Nor Asyikin Fadzil, and Yee Cheng Kueh. 2019. "Validation of the Malay Version of Mini-IPIP among Substance Use Disorder Patients Attending Methadone Clinics in Malaysia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 22: 4434. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224434

APA StyleLeong, F. W., Mohd Yasin, M. A., Muhd Ramli, E. R., Fadzil, N. A., & Kueh, Y. C. (2019). Validation of the Malay Version of Mini-IPIP among Substance Use Disorder Patients Attending Methadone Clinics in Malaysia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(22), 4434. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224434