Effects of a School Based Intervention on Children’s Physical Activity and Healthy Eating: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Intervention

2.3. Outcome Measures

2.4. Qualitative Method

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Measures

3.2. Intervention Effects

3.3. Intervention Effects Taking into Account Baseline Scores

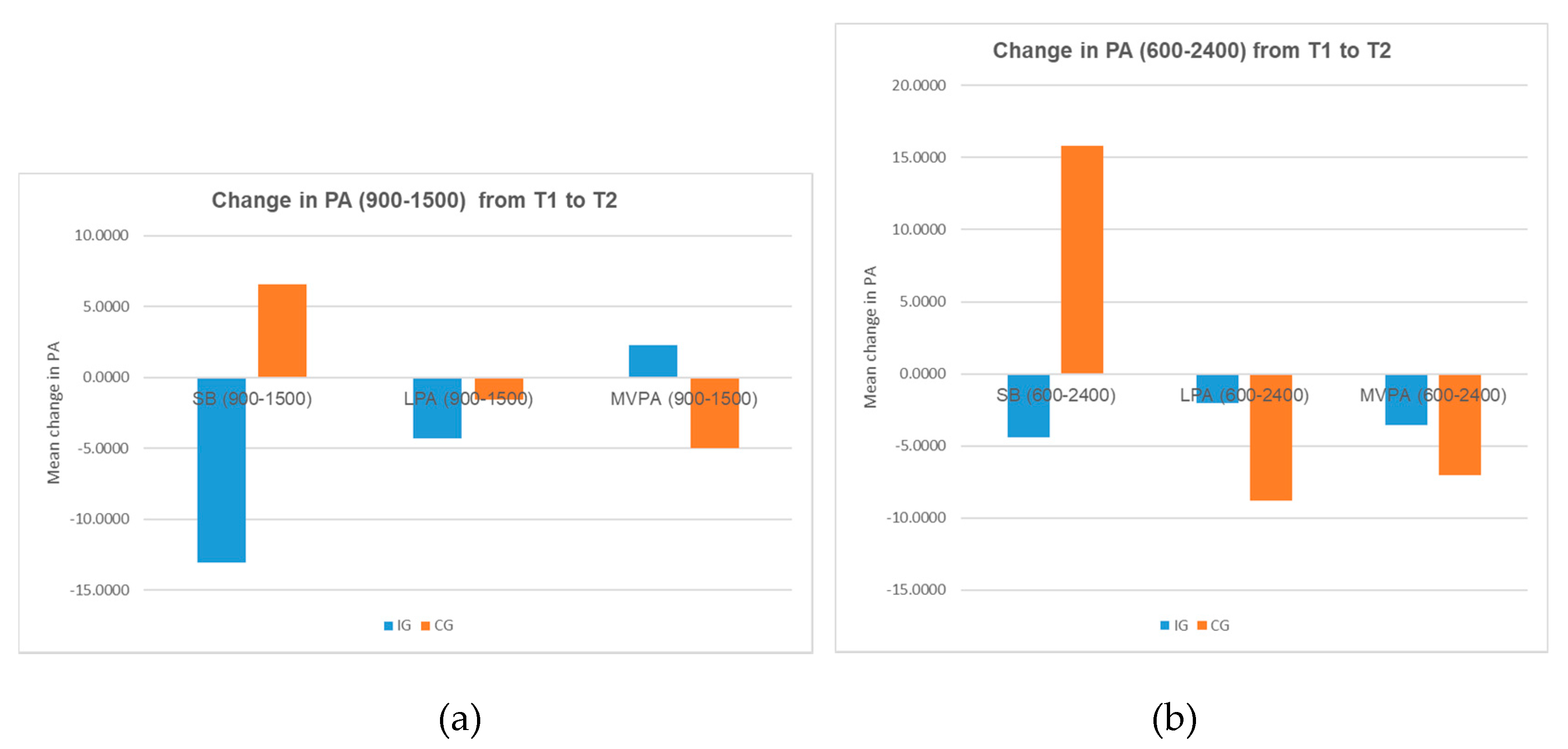

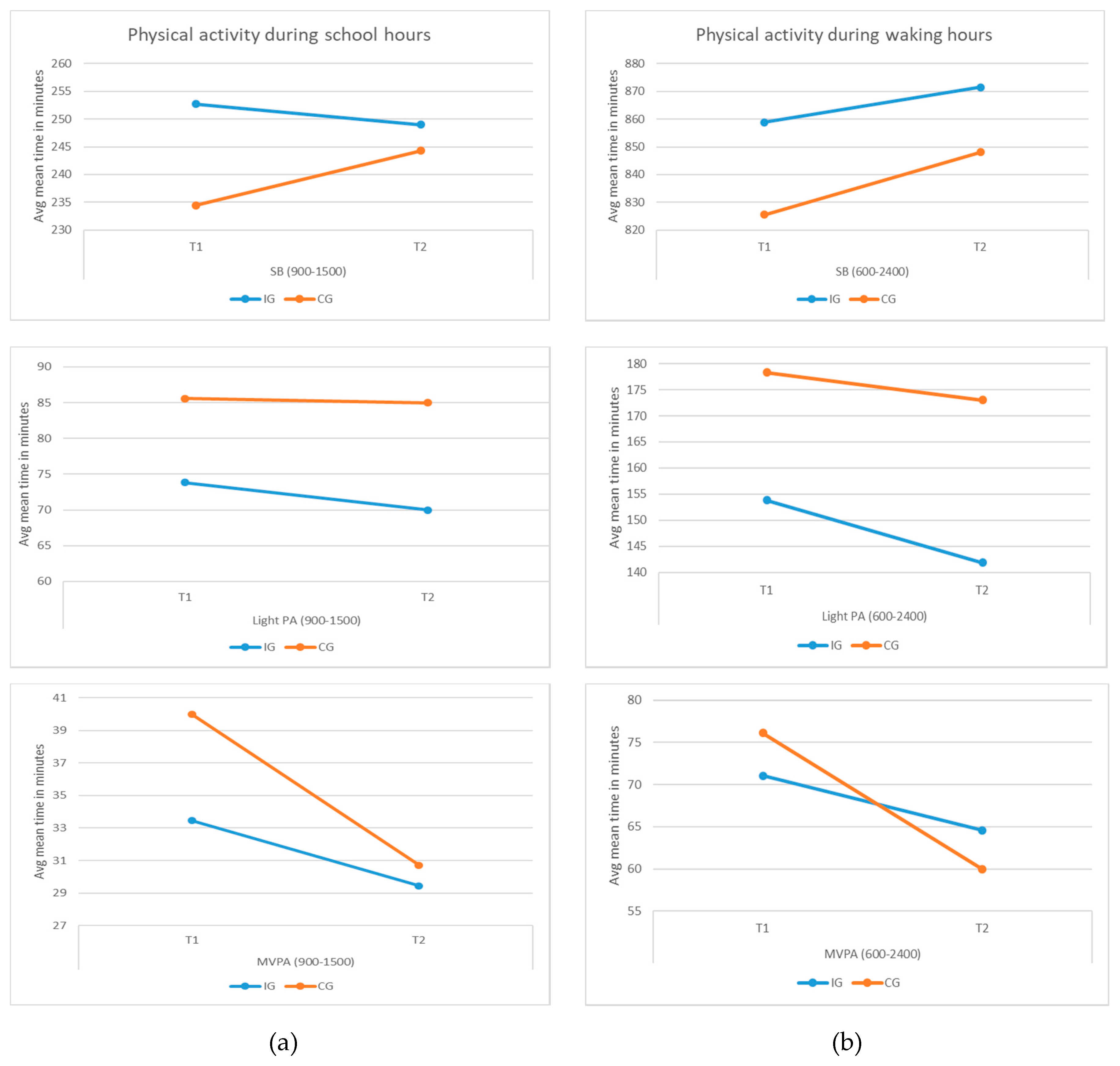

3.3.1. Sedentary Behaviour

3.3.2. Physical Activity

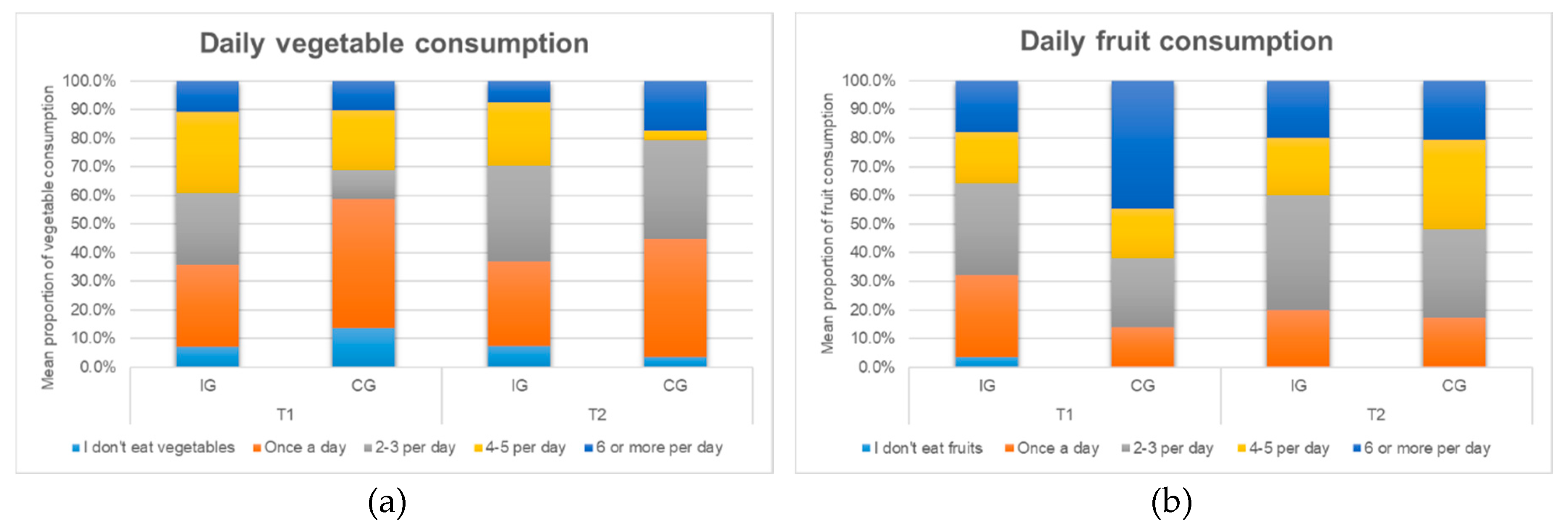

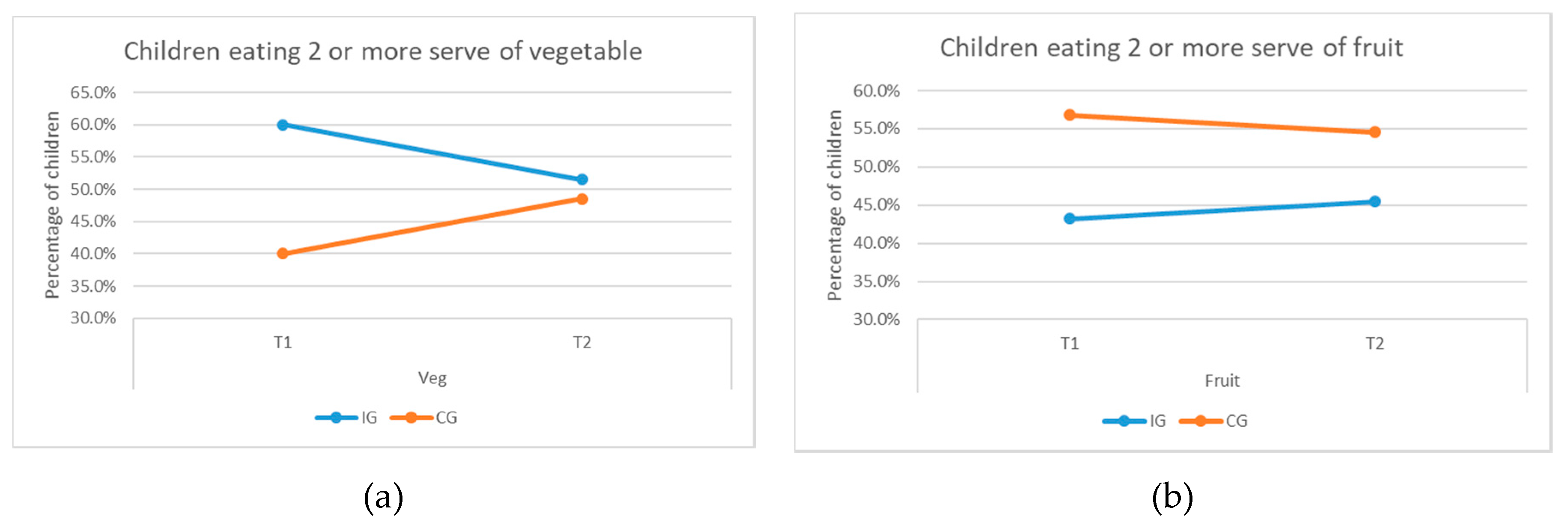

3.3.3. Daily Consumption of Vegetables and Fruits

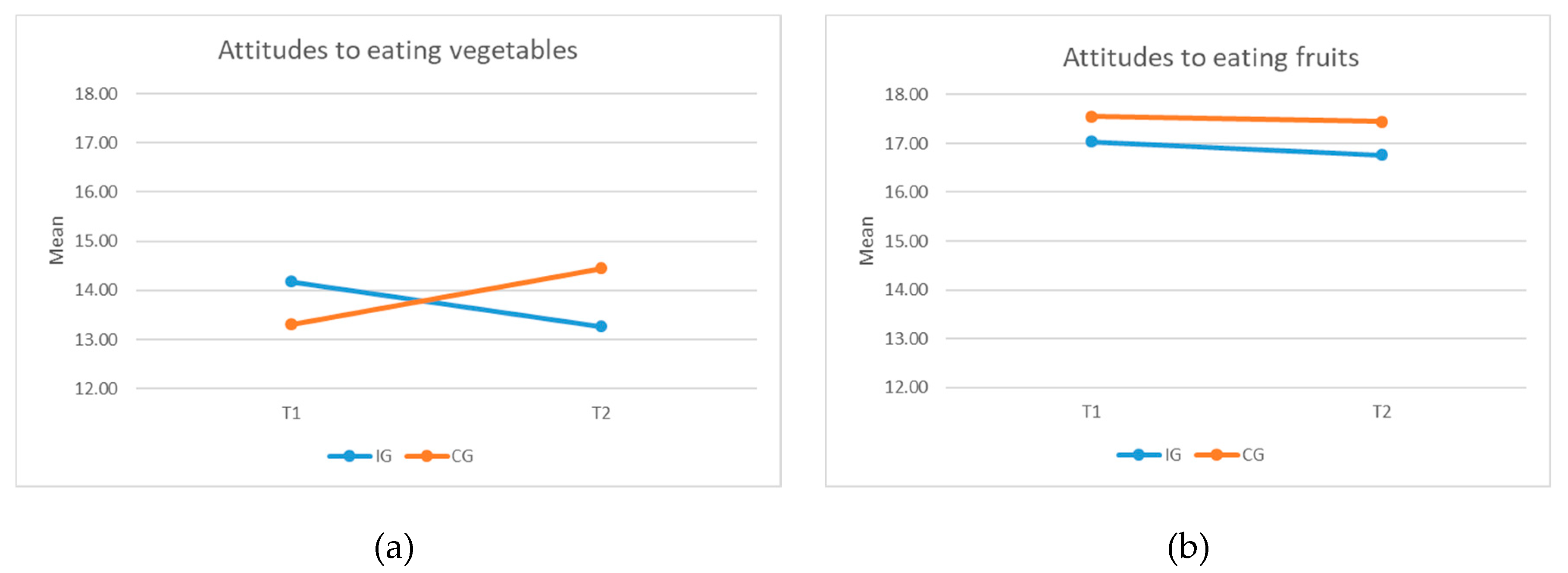

3.3.4. Attitude to Eating Vegetables and Fruits

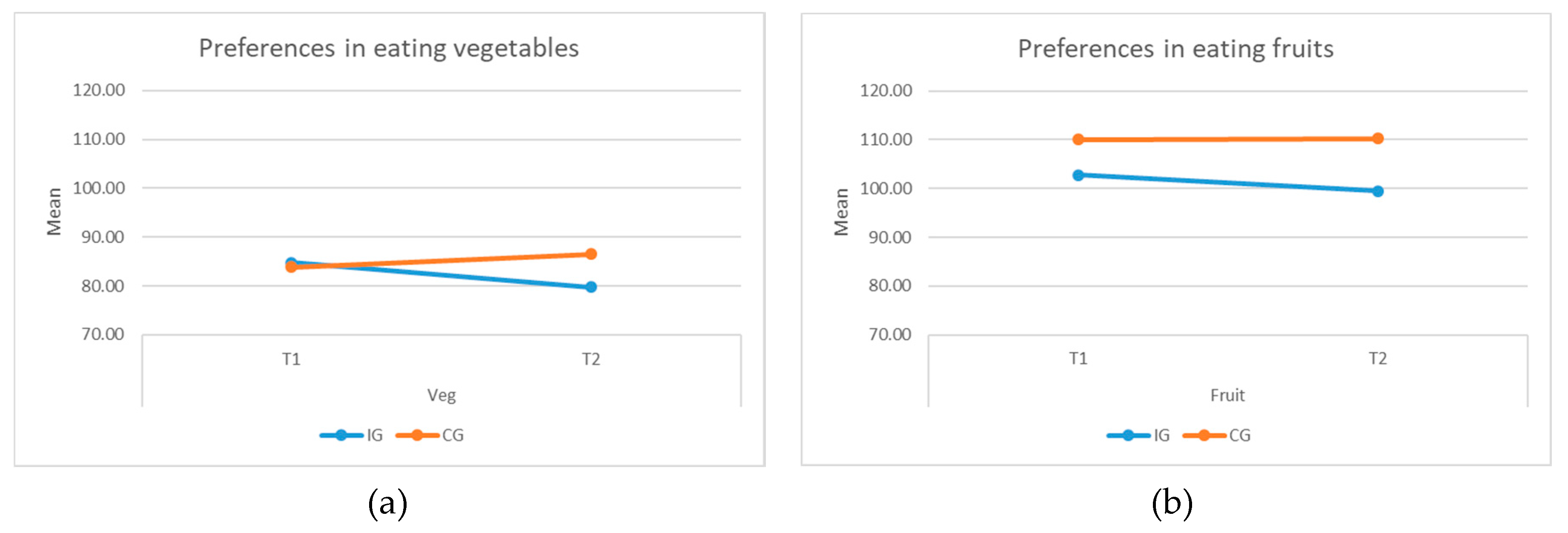

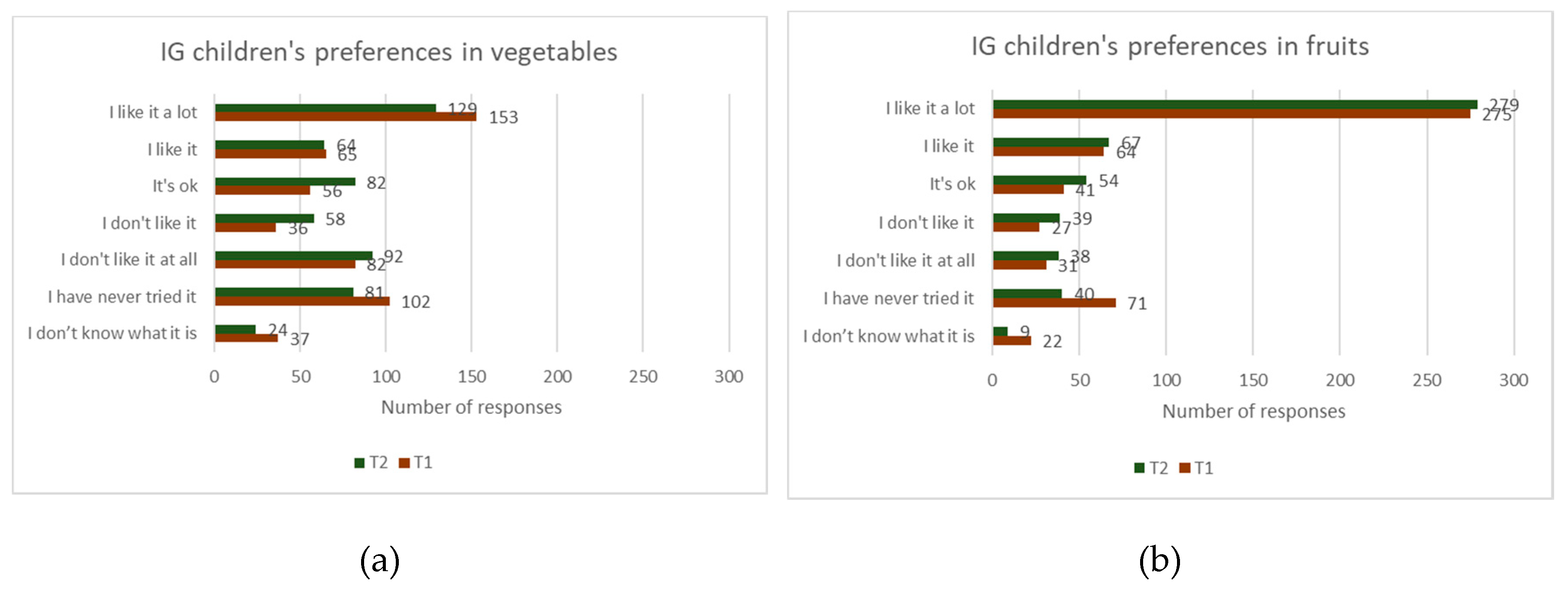

3.3.5. Preferences in Eating Vegetables and Fruits

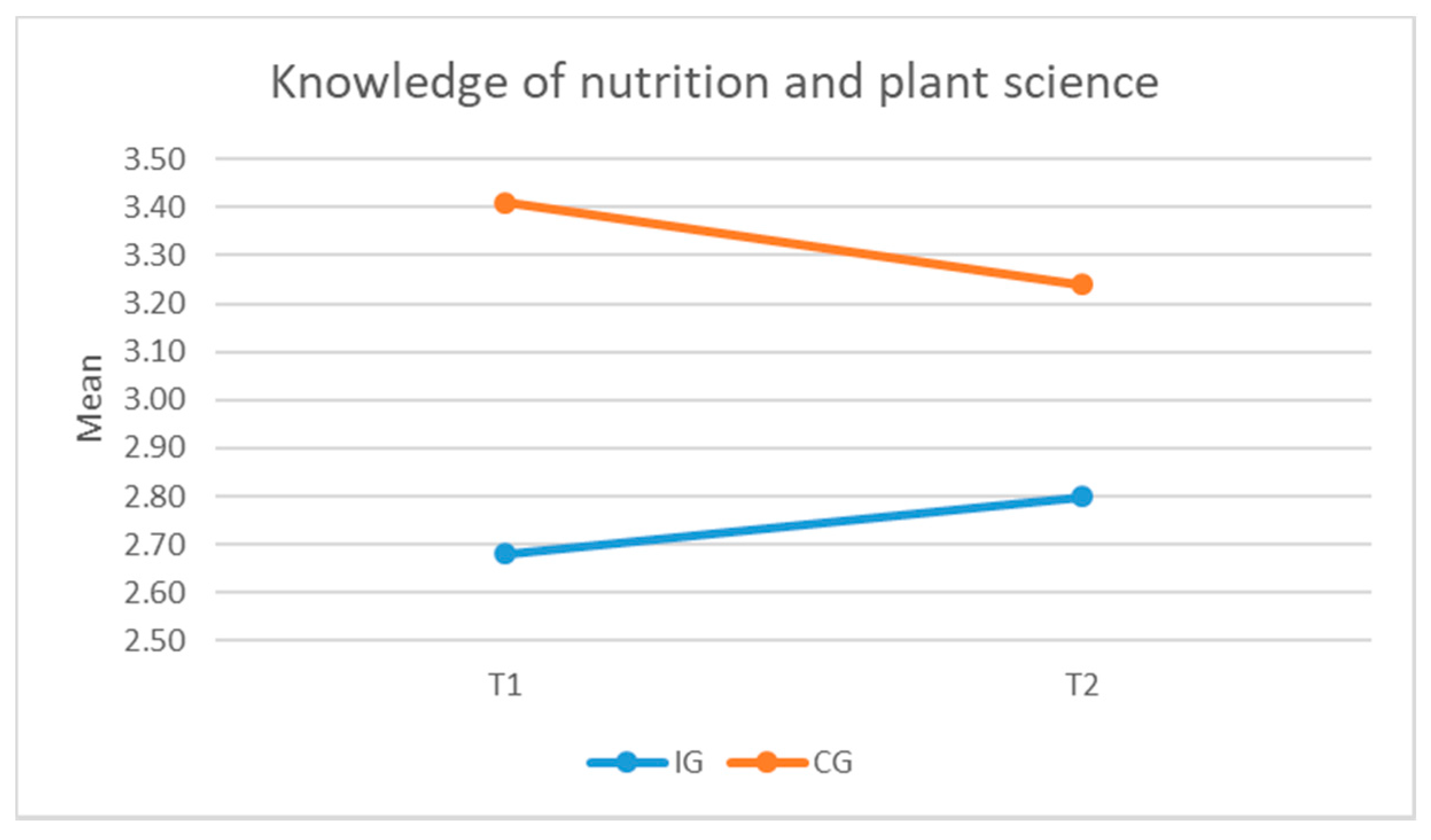

3.3.6. Knowledge of Nutrition and Plant Science

3.4. Qualitative Insights

3.4.1. Healthy Eating

Jack (All names used in the reporting of qualitative results are pseudonyms.): When like green gym wasn’t in our school I wasn’t really keen on vegetables, I wasn’t keen on like, whenever I had a meal at a restaurant I’d be like ‘oh mum can you eat my peas please cos I don’t want them?’Interviewer: YeahJack: But now I’m like, my mum asks ‘shall I take your peas?’ and I’m like ‘no I’m fine’

“Before green gyms started I used to love fruit but hate vegetables. And so, every time my mum put vegetables on my plate and I had something else with it, I’d just eat the other thing but then just leave all the vegetables away, but now if I look at them I won’t throw them away, I’d eat every single thing that’s on the plate and I wouldn’t moan about it”

“I don’t try food that much, but if I actually plant it, it might actually kinda make me try it.”

“Imagine if you plant your own food and you taste it, and you think ‘oh that’s really nice’ and eat more of that and eat less of like chocolate.”

“I think when Meat-Free Monday came in I actually tried to do Meat-Free Monday sometimes, but it’s not going very well, because lunches on Monday is always meat, so there was sausages. I was going to go for the vegetarian ones, but I tried that last time and they were not very nice.”

3.4.2. Physical Activity

“Because I’ve been walking around a lot and running so my legs are gaining muscle and my arms they’re always moving like chopping, raking or using shovels, and sometimes with the shovels there’s parts that are really hard but I push on and I’m able to get it up.”

“Cos I live in a house and I have a dog we usually just take her out in the garden but since green gym like when I get home from school ‘I’m like mum can we go walk the dog now?’ and she’d be like ‘yeah one minute’ and before I wouldn’t ask to walk the dog.”

3.4.3. Sociality

“Basically you can be put in groups that you don’t really like people and then like, you kind of get to know them, and like, you becoming friends with them, so it’s helping you in a way.”

“I feel like nature and plants and stuff bring people together. Because I remember, me and my friend had an argument. And then during Green Gym, we kind of slowly came back together.”

“Some people they’re naughty in class, but some people, when they went out there they were like helping everybody. Because there was someone who quickly learnt how to do it and he kept helping a bunch of people because he understanded (understood) and he wasn’t really playing around, and he was like sticking and understanding.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation

4.2. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Record High Levels of Severe Obesity Found in Year 6 Children. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/record-high-levels-of-severe-obesity-found-in-year-6-children (accessed on 23 May 2019).

- Conolly, A.; Davies, B. Health Survey for England 2017 Adult and Child Overweight and Obesity; NHS Digital: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, W.; Li, L.; Kuh, D.; Hardy, R. How Has the Age-Related Process of Overweight or Obesity Development Changed over Time? Co-ordinated Analyses of Individual Participant Data from Five United Kingdom Birth Cohorts. Lehman R, editor. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Child Measurement Programme. Available online: https://digital.nhs.uk/services/national-child-measurement-programme/ (accessed on 2 August 2018).

- Gurnani, M.; Birken, C.; Hamilton, J. Childhood Obesity. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 62, 821–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.C.; Lawlor, D.A.; Kimm, S.Y. Childhood obesity. Lancet 2010, 375, 1737–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hou, W.; Tang, Z.; Tang, Z. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ Open 2014, 4, 5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aune, D.; Giovannucci, E.; Boffetta, P.; Fadnes, L.T.; Keum, N.; Norat, T.; Greenwood, D.C.; Riboli, E.; Vatten, L.J.; Tonstad, S. Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality—A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1029–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craigie, A.M.; Lake, A.A.; Kelly, S.A.; Adamson, A.J.; Mathers, J.C. Tracking of obesity-related behaviours from childhood to adulthood: A systematic review. Maturitas 2011, 70, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahagan, S. Development of eating behavior: Biology and context. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2012, 33, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Inchley, J.; Currie, D.; Young, T.; Samdal, O.; Torsheim, T.; Augustson, L.; Mathisen, F.; Aleman-Dian, A.; Molcho, M.; Weber, M.; et al. Growing up Unequal: Gender and Socioeconomic Differences in Young People’s Health and Well-Being; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, L.J.; Cortina-Borja, M.; Sera, F.; Pouliou, T.; Geraci, M.; Rich, C.; Cole, T.J.; Law, C.; Joshi, H.; Ness, A.R.; et al. How active are our children? Findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucci, M.; Law, S.; Andrews, R.; Fisher, A.; Smith, L.; Sawyer, A.; Marmot, A. Indoor school environments, physical activity, sitting behaviour and pedagogy: A scoping review. Build. Res. Inf. 2015, 43, 566–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health and Social Care. Childhood Obesity: A Plan for Action Chapter 2; Department of Health and Social Care: London, UK, 2018.

- Sullivan, R.A.; Kuzel, A.H.; Vaandering, M.E.; Chen, W. The association of physical activity and academic behavior: A systematic review. J. Sch. Health 2017, 87, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.; McGeown, S. Designing for well-being: The influence of a schoolyard intervention on subjective well-being. BMJ Open 2019, 9 (Suppl. 1), A20–A21. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.; McGeown, S.P.; Islam, M.Z. ‘There is no better way to study science than to collect and analyse data in your own yard’: Outdoor classrooms and primary school children in Bangladesh. Child Geogr. 2019, 17, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Van Cauwenberghe, E.; Spittaels, H.; Oppert, J.M.; Rostami, C.; Brug, J.; Van Lenthe, F.; Lobstein, T.; Maes, L. School-based interventions promoting both physical activity and healthy eating in Europe: A systematic review within the HOPE project. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.; Summerbell, C. Systematic review of school-based interventions that focus on changing dietary intake and physical activity levels to prevent childhood obesity: An update to the obesity guidance produced by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Obes. Rev. 2009, 10, 110–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiner, M.; Niermann, C.; Jekauc, D.; Woll, A. Long-term health benefits of physical activity–a systematic review of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchette, L.; Brug, J. Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among 6–12-year-old children and effective interventions to increase consumption. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2005, 18, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cauwenberghe, E.; Maes, L.; Spittaels, H.; van Lenthe, F.J.; Brug, J.; Oppert, J.M.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I. Effectiveness of school-based interventions in Europe to promote healthy nutrition in children and adolescents: Systematic review of published and ‘grey’ literature. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 781–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.E.L.; Christian, M.S.; Cleghorn, C.L.; Greenwood, D.C.; Cade, J.E. Systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based interventions to improve daily fruit and vegetable intake in children aged 5 to 12 y. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly, H.; Gentry, S.; Wigglesworth, R.; Bethel, A.; Lovell, R.; Garside, R. A systematic review of the health and well-being impacts of school gardening: Synthesis of quantitative and qualitative evidence. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 286. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, J.L.; Zidenberg-Cherr, S. Garden-enhanced nutrition curriculum improves fourth-grade school children’s knowledge of nutrition and preferences for some vegetables. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2002, 102, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, N.M.; Ventura, E.E.; Cook, L.T.; Gyllenhammer, L.E.; Davis, J.N. LA Sprouts: A Garden-Based Nutrition Intervention Pilot Programme Influences Motivation and Preferences for Fruits and Vegetables in Latino Youth. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, K.; Hemingway, A.; Saulais, L.; Dinnella, C.; Monteleone, E.; Depezay, L.; Castagna, E.; Perez-Cueto, F.J.; Bevan, A.; Hartwell, H. Increasing Vegetable Intakes: An Updated Systematic Review of Published Interventions. In Advances in Vegetable Consumption and Health Research; Schneider, K., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: Colombia, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 85–154. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, N.M.; Myers, B.M.; Henderson, C.R. School gardens and physical activity: A randomized controlled trial of low-income elementary schools. Prev. Med. 2014, 69, S27–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees-Punia, E.; Holloway, A.; Knauft, D.; Schmidt, M.D. Effects of School Gardening Lessons on Elementary School Children’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Time. J. Phys. Act. Health 2017, 14, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.N.; Spaniol, M.R.; Somerset, S.; Somerset, S. Sustenance and sustainability: Maximizing the impact of school gardens on health outcomes. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2358–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Vliet, N.; Staatsen, B.; Kruize, H.; Morris, G.; Costongs, C.; Bell, R.; Marques, S.; Taylor, T.; Quiroga, S.; Martinez Juarez, P.; et al. The INHERIT Model: A Tool to Jointly Improve Health, Environmental Sustainability and Health Equity through Behavior and Lifestyle Change. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvalán, C.; Briggs, D.; Kjellstrom, T. Development of Environmental Health Indicators; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S.; Atkins, L.; West, R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guid to Designing Interventions, 1st ed.; Silverback Publishing: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- London Borough of Redbridge. London Borough of Redbridge Borough Profile; London Borough of Redbridge: London, UK, 2015.

- TCV. School Green Gym: Evaluation Findings: Health and Social Outcomes. Available online: https://www.tcv.org.uk/sites/default/files/school-green-gym-evaluation-findings.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2018).

- Wilson, A.M.; Magarey, A.M.; Mastersson, N. Reliability and relative validity of a child nutrition questionnaire to simultaneously assess dietary patterns associated with positive energy balance and food behaviours, attitudes, knowledge and environments associated with healthy eating. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, N.M.; Myers, B.M.; Todd, L.E.; Barale, K.; Gaolach, B.; Ferenz, G.; Aitken, M.; Henderson, C.R.; Tse, C.; Pattison, K.O.; et al. The Effects of School Gardens on Children’s Science Knowledge: A randomized controlled trial of low-income elementary schools. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2015, 37, 2858–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hees, V.T.; Gorzelniak, L.; Leon, E.C.; Eder, M.; Pias, M.; Taherian, S.; Ekelund, U.; Renström, F.; Franks, P.W.; Horsch, A.; et al. Separating movement and gravity components in an acceleration signal and implications for the assessment of human daily physical activity. Müller M, editor. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P.J.; Warren, J.M.; Lubans, D.R.; Saunders, K.L.; Quick, G.I.; Collins, C.E. The impact of nutrition education with and without a school garden on knowledge, vegetable intake and preferences and quality of school life among primary-school students. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 1931–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanaugh, K. Project Learning Garden: A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of the Evaluation Techniques on School Gardens; Public Health Theses School of Public Health; Georgia State University: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo, S.J.; Yang, S.-J.; Hughes, S.O.; Fisher, J.O.; Morales, M.; Nicklas, T.A. Interactive Computerized Fruit and Vegetable Preference Measure for African-American and Hispanic Preschoolers. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2006, 38, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huys, N.; Cardon, G.; De Craemer, M.; Hermans, N.; Renard, S.; Roesbeke, M.; Stevens, W.; De Lepeleere, S.; Deforche, B. Effect and process evaluation of a real-world school garden programme on vegetable consumption and its determinants in primary schoolchildren. Conklin AI, editor. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarti, A.; Dijkstra, C.; Nury, E.; Seidell, J.C.; Dedding, C. ‘I Eat the Vegetables because I Have Grown them with My Own Hands’: Children’s Perspectives on School Gardening and Vegetable Consumption. Child Soc. 2017, 31, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliffe, M.M.; Merrigan, K.A.; Rogers, B.L.; Goldberg, J.P. The Effects of School Garden Experiences on Middle School-Aged Students’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors Associated with Vegetable Consumption. Health Promot. Pract. 2011, 12, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, T.J.; Chaput, J.-P.; Tremblay, M.S. Sedentary Behaviour as an Emerging Risk Factor for Cardiometabolic Diseases in Children and Youth. Can. J. Diabetes 2014, 38, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leech, R.M.; McNaughton, S.A.; Timperio, A. Clustering of diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour among Australian children: Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations with overweight and obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2015, 39, 1079–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M.J.; Eyre, E.; Bryant, E.; Clarke, N.; Birch, S.; Staples, V.; Sheffield, D. The impact of a school-based gardening intervention on intentions and behaviour related to fruit and vegetable consumption in children. J. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Evans, C.E.L.; Nykjaer, C.; Hancock, N.; Cade, J.E. Evaluation of the impact of a school gardening intervention on children’s fruit and vegetable intake: A randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezowitz, C.K.; Bontrager Yoder, A.B.; Schoeller, D.A. School Gardens Enhance Academic Performance and Dietary Outcomes in Children. J. Sch. Health 2015, 85, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuven, J.R.F.W.; Rutenfrans, A.H.M.; Dolfing, A.G.; Leuven, R.S.E.W. School gardening increases knowledge of primary school children on edible plants and preference for vegetables. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 1960–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lippevelde, W.; Verloigne, M.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Brug, J.; Bjelland, M.; Lien, N.; Maes, L. Does parental involvement make a difference in school-based nutrition and physical activity interventions? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Public Health 2012, 57, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Story, M.; Nanney, M.S.; Schwartz, M.B. Schools and Obesity Prevention: Creating School Environments and Policies to Promote Healthy Eating and Physical Activity. Milbank Q. 2009, 87, 71–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckson, R.V. America’s Childhood Obesity Crisis and the Role of Schools. J. Sch. Health 2013, 83, 137–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewallen, T.C.; Hunt, H.; Potts-Datema, W.; Zaza, S.; Giles, W. The Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child Model: A New Approach for Improving Educational Attainment and Healthy Development for Students. J. Sch. Health 2015, 85, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Deprivation Index | Percentage of Children |

|---|---|

| 0%−10% most deprived | 4.2% |

| 10%−20% | 13.6% |

| 20%−30% | 18.4% |

| 30%−40% | 4.6% |

| 40%−50% | 10% |

| 50%−60% | 5.9% |

| 60%−70% | 16.9% |

| 70%−80% | 4% |

| 80%−90% | 0.8% |

| 90%−100% least deprived | 1.3% |

| Category Score (Total Items) | Items in Each Score | Number of Items | Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | |||

| Fruit (4) | With regards to fruit, agreement with: makes me feel healthy, tastes good, easy snack, I like tasting new fruits | 4 | Likert scale (1 to 5) |

| Vegetable (4) | With regards to vegetables, agreement with: makes me feel healthy, tastes good, I like tasting new vegetables, easy to prepare | 4 | Likert scale (1 to 5) |

| Frequency | |||

| Fruit (1) | Number of servings of fruit consumed by you each day | 1 | Select from: none, 1 a day, 2–3 a day, 4−5 a day, 6 or more per day |

| Vegetables (1) | Number of servings of vegetables consumed by you each day | 1 | Select from: none, 1 a day, 2–3 a day, 4−5 a day, 6 or more per day |

| Preferences | |||

| Fruit (19) | How much you like the fruits in the picture (19 fruit items that are easily available in the UK) | 19 | Select from: I like it a lot, I like it, It’s ok, I don’t like it, I don’t like it at all, I have never tried it and I don’t know what it is |

| Vegetable (19) | How much you like the vegetables in the picture (19 vegetables items that are easily available in the UK) | 19 | Select from: I like it a lot, I like it, It’s ok, I don’t like it, I don’t like it at all, I have never tried it and I don’t know what it is |

| Knowledge of plant science and nutrition | |||

| Knowledge (7) | 7 questions on what people and plants need to live, which nutrient supplies energy, which part of a the plant we eat when eating broccoli, which nutrient do we want to see on a food label, which part of the plant uses the sun’s energy, which item is not an ingredient for making compost, and which part of the plant pulls water and other nutrients from the soil | 7 | Select one from four options |

| Measures | Total | Intervention Group (IG) Mean (SD) | Control Group (CG) Mean (SD) | p-Value for Difference between IG and CG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 8.92 (1.20) | 9.07 (0.25) | 9.07 (0.25) | 0.97 |

| Sex in % girls | 39.0% | 40% | 37.9% | 0.87 |

| Sedentary Behaviour | ||||

| SB (900−1500), minutes | 244.01 (27.51) | 252.72 (32.39) | 234.45 (18.23) | 0.042 * |

| SB (600−2400), minutes | 839.31 (61.75) | 858.91 (73.15) | 825.55 (50.28) | 0.137 |

| Physical Activity | ||||

| LPA (900−1500), minutes | 79.58 (16.96) | 73.82 (19.72) | 85.56 (11.32) | 0.033 * |

| MVPA (900−1500), minutes | 36.40 (13.25) | 33.46 (14.49) | 39.99 (11.49) | 0.135 |

| LPA (600−2400), minutes | 168.55 (41.91) | 153.83 (49.35) | 178.31 (33.32) | 0.105 |

| MVPA (600−2400), minutes | 73.33 (28.37) | 71.067 (31.37) | 76.140 (26.15) | 0.594 |

| Healthy eating | ||||

| Daily vegetable consumption | 2.88 (1.21) | 3.07 (1.15) | 2.69 (1.26) | 0.24 |

| Daily fruit consumption | 3.56 (1.20) | 3.18 (1.15) | 3.93 (1.13) | 0.016 * |

| Attitude to eating vegetables | 13.74 (3.33) | 14.18 (3.69) | 13.31 (2.94) | 0.33 |

| Attitude to eating fruits | 17.30 (2.68) | 17.04 (2.94) | 17.55 (2.44) | 0.47 |

| Preferences of vegetable | 84.26 (22.08) | 84.71 (22.09) | 83.83 (22.45) | 0.88 |

| Preferences of fruit | 106.51 (21.24) | 102.82 (23.17) | 110.07 (18.91) | 0.20 |

| Knowledge of nutrition | ||||

| Knowledge of nutrition and plant science | 3.05 (1.58) | 2.68 (1.39) | 3.41 (1.70) | 0.08 |

| Intervention Group (IG) | Control Group (CG) | p-Value for Difference between IG and CG | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Sedentary Behaviour | |||

| SB (900−1500), minutes | 248.97 (62.11) | 244.29 (17.90) | 0.829 |

| SB (600−2400), minutes | 871.46 (93.42) | 848.11 (32.76) | 0.508 |

| Physical Activity | |||

| LPA (900−1500), minutes | 69.97 (30.55) | 84.99 (11.32) | 0.173 |

| MVPA (900−1500), minutes | 29.44 (17.55) | 30.71 (8.88) | 0.842 |

| LPA (600−2400), minutes | 141.90 (69.65) | 172.99(23.29) | 0.244 |

| MVPA (600−2400), minutes | 64.56 (27.51) | 60.00 (10.84) | 0.640 |

| Healthy Eating | |||

| Daily vegetable consumption | 2.88 (1.09) | 2.90 (1.14) | 0.346 |

| Daily fruit consumption | 3.35 (1.07) | 3.55 (1.02) | 0.728 |

| Attitude to eating vegetables | 13.07 (4.76) | 14.45 (3.35) | 0.085 |

| Attitude to eating fruits | 16.61 (5.07) | 17.45 (2.63) | 0.480 |

| Preferences of vegetable | 77.96 (29.82) | 86.55 (17.66) | 0.078 |

| Preferences of fruit | 97.79 (33.05) | 110.24 (17.49) | 0.229 |

| Knowledge of nutrition | |||

| Knowledge of nutrition and plant science | 2.79 (1.75) | 3.24 (1.76) | 0.681 |

| Mean Change in PA | IG | CG | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | ||

| SB (900−1500) | 12 | −13.0388 | 64.73694 | 7 | 6.5423 | 17.21601 | 0.449 |

| LPA (900−1500) | 11 | −4.2775 | 24.50218 | 7 | −1.5536 | 13.02090 | 0.791 |

| MVPA (900−1500) | 11 | 2.3062 | 20.28664 | 7 | −4.9887 | 7.18188 | 0.378 |

| SB (600−2400) | 8 | −4.4342 | 34.05974 | 7 | 15.8296 | 23.07180 | 0.207 |

| LPA (600−2400) | 8 | −2.0128 | 28.46088 | 7 | −8.8024 | 19.49796 | 0.605 |

| MVPA (600−2400) | 11 | −3.5358 | 45.18339 | 7 | −7.0268 | 10.76162 | 0.845 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, M.; Bell, R. Effects of a School Based Intervention on Children’s Physical Activity and Healthy Eating: A Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4320. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224320

Khan M, Bell R. Effects of a School Based Intervention on Children’s Physical Activity and Healthy Eating: A Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(22):4320. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224320

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Matluba, and Ruth Bell. 2019. "Effects of a School Based Intervention on Children’s Physical Activity and Healthy Eating: A Mixed-Methods Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 22: 4320. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224320

APA StyleKhan, M., & Bell, R. (2019). Effects of a School Based Intervention on Children’s Physical Activity and Healthy Eating: A Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(22), 4320. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224320