A Scoping Review and Conceptual Model of Social Participation and Mental Health among Refugees and Asylum Seekers

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Mental Health of RAS

1.2. Gaps in Knowledge and Rationale for This Study

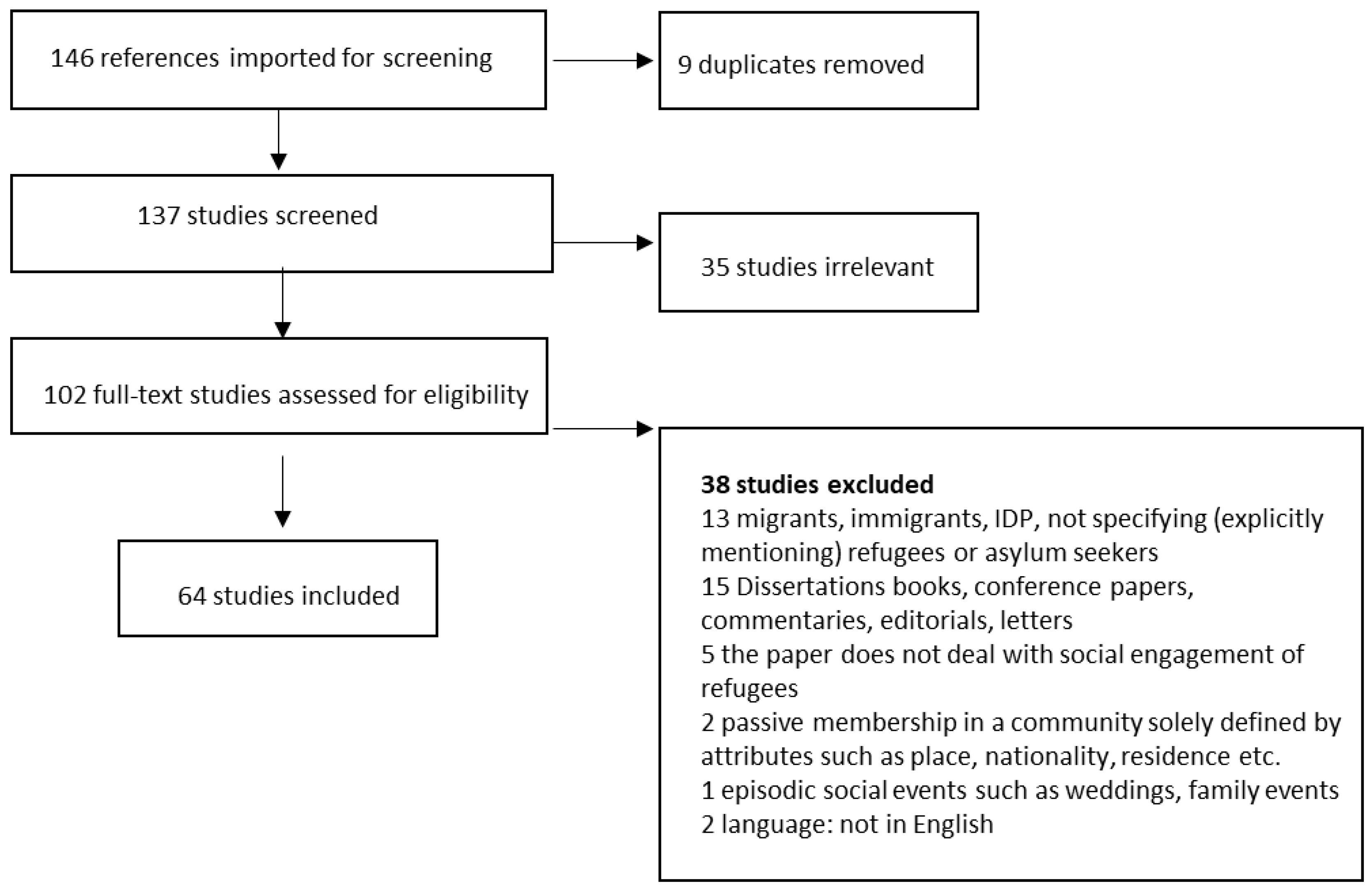

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategies

2.2. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

- (a)

- Concepts and methods addressed regarding social participation among RAS.

- (b)

- Associations between social participation and mental health among RAS.

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Studies

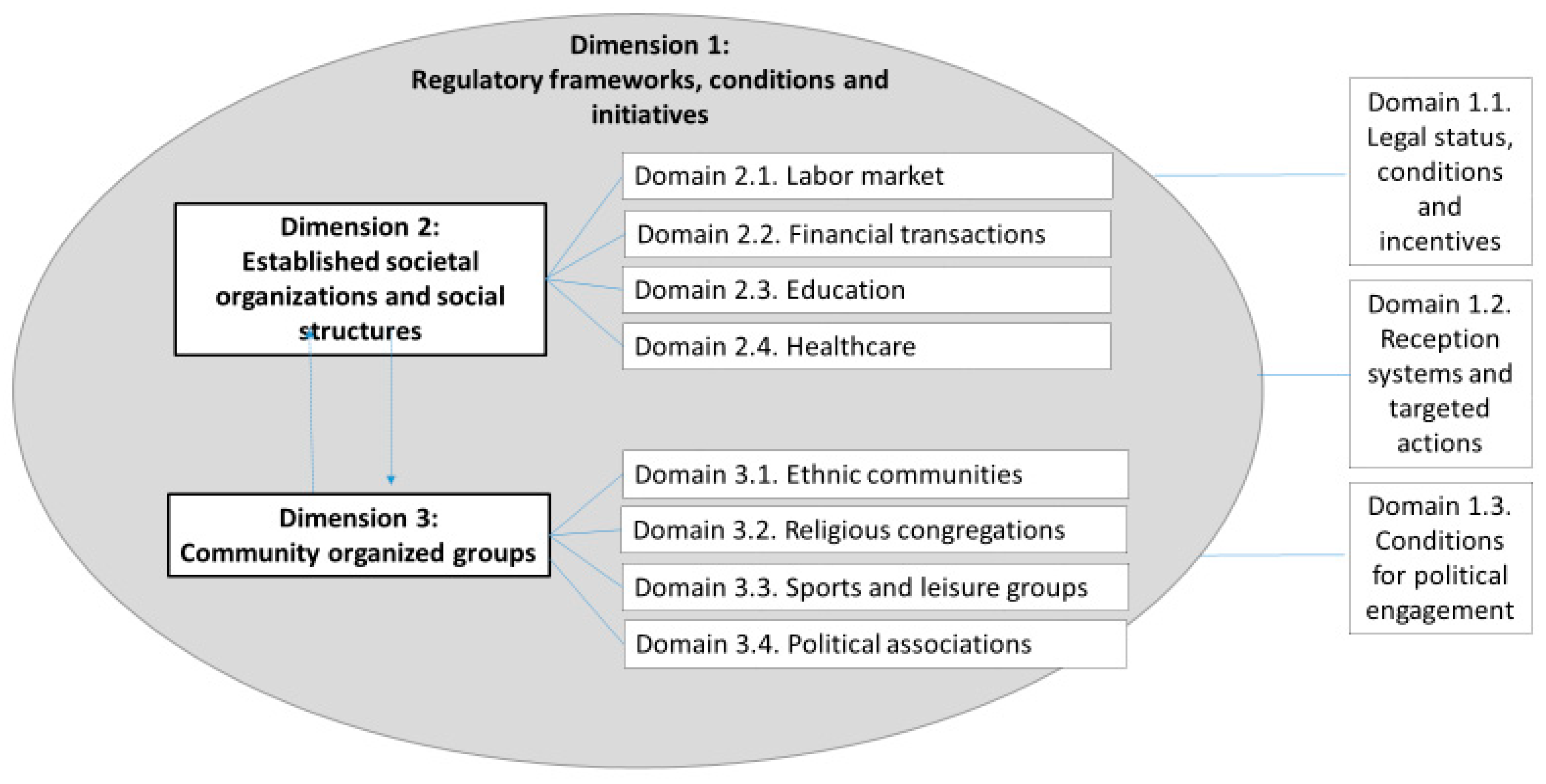

3.2. Social Participation among RAS—Definitions and Conceptual Model

- Regulations and frameworks, conditions and initiatives

- Established societal organizations

- Community organized groups

3.3. Dimension 1: Regulatory Frameworks, Conditions and Initiatives

3.3.1. Domain 1.1. Legal Status, Conditions and Incentives

3.3.2. Domain 1.2. Reception Systems and Targeted Actions

3.3.3. Domain 1.3. Conditions for Political Engagement

3.4. Dimension 2: Established Societal Organizations and Social Structures

3.4.1. Domain 2.1 Labor Market

3.4.2. Domain 2.2 Financial Transactions

3.4.3. Domain 2.3 Education

3.4.4. Domain 2.4 Healthcare

3.5. Dimension 3: Community Organized Groups

3.5.1. Domain 3.1 Ethnic Communities

3.5.2. Domain 3.2 Religious Congregations

3.5.3. Domain 3.3 Sports and Leisure Groups

3.5.4. Domain 3.4 Political Associations

3.5.5. Mental Health Classifications

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author, Year | Clear Aim | Study Population | Participation Rate | Inclusion and Exclusion | Power Calculation | Exposure | Tieframe | Exposure Level | Exposure Measure | Repeated Assessment | Outcome Variable | Blinding | Dropout | Confounders | Overall Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khawaja, 2006 [19] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | CD | NR | Yes | Excellent |

| Stewart, 2015 [39] | Yes | Yes | CD | Yes | No | Yes | No | CD | Yes | No | Yes | CD | No | Yes | Good |

| Fozdar, 2011 [48] | Yes | Yes | CD | CD | No | No | No | CD | CD | No | CD | CD | NA | Yes | Weak |

| Montgomery, 1987 [49] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | NR | NA | Yes | Excellent |

| Bach, 1986 [50] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | CD | NA | Yes | No | Yes | CD | NA | Yes | Good |

| Caspi, 1998 [51] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | NA | No | Yes | No | Yes | CD | NA | Yes | Good |

| Thanh Van, 1987 [55] | Yes | CD | CD | CD | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | CD | NR | Yes | Good |

| Gerber, 2017 [57] | Yes | Yes | NR | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | CD | NA | Yes | Weak |

| Haddad, 2002 [66] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | CD | NA | Yes | Excellent |

| Aylesworth, 1983 [67] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | NA | CD | No | CD | NR | NA | Yes | Good |

| Hitch, 1980 [76] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | CD | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | CD | No | Yes | Excellent |

| Makhoul, 2009 [84] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | CD | Yes | No | Yes | CD | NA | CD | Weak |

| Jeong, 2016 [87] | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | No | No | CD | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | CD | NR | Yes | Excellent |

Appendix B

| Author, Year | Appropriate Sample | Data Collection | Analysis | Transferability | Ethics | Clarity | Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown, 2011 [32] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | Excellent |

| Da Lomba, 2010 [33] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Korac, 2003 [34] | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Weak |

| Stewart, 2014 [35] | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Baban, 2016 [36] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Ingvarsson, 2016 [37] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Ricento, 2013 [38] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Weak |

| Stewart, 2015 [39] | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Hynes, 2009 [40] | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Barnes,2001 [41] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | Excellent |

| Hagelund, 2009 [42] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Weak |

| Shindo, 2009 [43] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Weak |

| Horst, 2013 [44] | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | Weak |

| Neudorf, 2016 [45] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Weak |

| Valtonen, 1998 [46] | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | Excellent |

| Valtonen, 1999 [47] | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | Excellent |

| Fozdar, 2011 [48] | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Ramaliu, 2003 [52] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Weak |

| Abraham, 2004 [53] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Preston, 1992 [54] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Weak |

| Gil-Garcia, 2015 [56] | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Weak |

| Gerber, 2017 [57] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | Excellent |

| Hope, 2011 [58] | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Marsh, 2012 [59] | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | Satisfactory |

| Pugh, 2017 [60] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Weak |

| Naidoo, 2009 [61] | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | Excellent |

| Earnest, 2015 [62] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | Excellent |

| Barnes, 2007 [63] | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | Excellent |

| Dandy, 2013 [64] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | Excellent |

| Evans, 2011 [65] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | Weak |

| Yelland, 2014 [68] | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Lazar, 2013 [69] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | Satisfactory |

| Conviser, 2007 [70] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | Weak |

| Cheng, 2015 [71] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Pejic, 2017 [72] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Weak |

| Worabo, 2017 [73] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Lindgren, 2004 [74] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Riggs, 2015 [75] | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | Satisfactory |

| Al-Ali, 2001 [77] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Bloemraad, 2005 [78] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Casier, 2010 [79] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Casier, 2011 [80] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Weak |

| Weng, 2016 [81] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Weak |

| Fox, 2012 [82] | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Hein, 2014 [83] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Makhoul, 2009 [84] | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | Satisfactory |

| Achilli, 2014 [85] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Weak |

| Rosso, 2016 [86] | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | Satisfactory |

| Østergaard-Nielsen, 2001 [88] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Weak |

| Rivetti, 2013 [89] | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Grossman, 2014 [90] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | Weak |

| Matthews, 2008 [91] | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Eggert, 2015 [92] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | Satisfactory |

| Whiteford, 2007 [93] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Weak |

| Stack, 2009 [94] | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | Satisfactory |

References

- Global Trends Forced Displacement in 2016; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Grzymala-Kazlowska, A.; Phillimore, J. Introduction: Rethinking integration. New perspectives on adaptation and settlement in the era of super-diversity. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2017, 44, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morina, N.; Akhtar, A.; Barth, J.; Schnyder, U. Psychiatric Disorders in Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons After Forced Displacement: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norredam, M.; Mygind, A.; Krasnik, A. Access to health care for asylum seekers in the European Union—A comparative study of country policies. Eur. J. Public Health 2005, 16, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeary, M.; Newbold, B. Barriers to care: The challenges for Canadian refugees and their health care providers. J. Refug. Stud. 2010, 23, 523–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, M.; Reed, R.V.; Panter-Brick, C.; Stein, A. Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in high-income countries: Risk and protective factors. Lancet 2012, 379, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.E.; Rasmussen, A. War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: Bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribe, R. Mental health of refugees and asylum-seekers. Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. 2002, 8, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.E.; Rasmussen, A. War experiences, daily stressors and mental health five years on: Elaborations and future directions. Intervention 2014, 12, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silove, D.; Ventevogel, P.; Rees, S. The contemporary refugee crisis: An overview of mental health challenges. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.; Rasmussen, A. The mental health of civilians displaced by armed conflict: An ecological model of refugee distress. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2017, 26, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.E.; Worthington, G.J.; Muzurovic, J.; Tipping, S.; Goldman, A. Bosnian refugees and the stressors of exile: A narrative study. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2002, 72, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNHCR. Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugee; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ager, A.; Strang, A. Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework. J. Refug. Stud. 2008, 21, 166–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzymala-Kazlowska, A. From Connecting to Social Anchoring: Adaptation and ‘Settlement’ of Polish Migrants in the UK. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2017, 44, 252–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castles, S.; Korac, M.; Vasta, E.; Vertovec, S. Integration: Mapping the field. Home Off. Online Rep. 2002, 29, 115–118. [Google Scholar]

- Clapp, J.D.; Beck, J.G. Understanding the relationship between PTSD and social support: The role of negative network orientation. Behav. Res. Ther. 2009, 47, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.M.; Rostila, M.; Svensson, A.C.; Engström, K. The role of social capital in explaining mental health inequalities between immigrants and Swedish-born: A population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, M.; Tewtel-Salem, M.; Obeid, M.; Saliba, M. Civic engagement, gender and self-rated health in poor communities: Evidence from Jordan’s refugee camps. Health Sociol. Rev. 2006, 15, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, M.; Hanson, B.S.; Östergren, P.-O. Socioeconomic differences in leisure-time physical activity: The role of social participation and social capital in shaping health related behaviour. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 52, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyyppä, M.T.; Mäki, J. Social participation and health in a community rich in stock of social capital. Health Educ. Res. 2003, 18, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, I.; Berkman, L.F. Social ties and mental health. J. Urban Health 2001, 78, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, J.; Susser, E. Social integration in global mental health: What is it and how can it be measured? Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2013, 22, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Blue, G.; Rosol, M.; Fast, V. Justice as Parity of Participation: Enhancing Arnstein’s Ladder Through Fraser’s Justice Framework. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2019, 85, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakewell, O. Some Reflections on Structure and Agency in Migration Theory. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2010, 36, 1689–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIPEX. Migrant Integration Policy Index. 2015. Available online: http://www.mipex.eu/ (accessed on 15 June 2019).

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, M.T.; Rajić, A.; Greig, J.D.; Sargeant, J.M.; Papadopoulos, A.; McEwen, S.A. A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res. Synth. Methods 2014, 5, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIH. Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools/cohort (accessed on 12 July 2017).

- Kuper, A.; Lingard, L.; Levinson, W. Critically appraising qualitative research. Br. Med. J. 2008, 337, a1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.E. Refugees, Rights, and Race: How Legal Status Shapes Liberian Immigrants’ Relationship with the State. Soc. Probl. 2011, 58, 144–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Lomba, S. Legal Status and Refugee Integration: A UK Perspective. J. Refug. Stud. 2010, 23, 415–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korac, M. Integration and How We Facilitate It: A Comparative Study of the Settlement Experiences of Refugees in Italy and the Netherlands. Sociology 2003, 37, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, E.; Mulvey, G. Seeking Safety beyond Refuge: The Impact of Immigration and Citizenship Policy upon Refugees in the UK. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2014, 40, 1023–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baban, F.; Ilcan, S.; Rygiel, K. Syrian refugees in Turkey: Pathways to precarity, differential inclusion, and negotiated citizenship rights. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2017, 43, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingvarsson, L.; Egilson, S.T.; Skaptadottir, U.D. “I want a normal life like everyone else”: Daily life of asylum seekers in Iceland. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2016, 23, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricento, T. Dis-citizenship for refugees in Canada: The case of Fernando. J. Lang. Identity Educ. 2013, 12, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.; Makwarimba, E.; Letourneau, N.L.; Kushner, K.E.; Spitzer, D.L.; Dennis, C.-L.; Shizha, E. Impacts of a support intervention for Zimbabwean and Sudanese refugee parents: “I am not alone”. CJNR Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2015, 47, 113–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, P. Contemporary Compulsory Dispersal and the Absence of Space for the Restoration of Trust. J. Refug. Stud. 2009, 22, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D. Resettled Refugees’ Attachment to Their Original and Subsequent Homelands: Long-Term Vietnamese Refugees in Australia. J. Refug. Stud. 2001, 14, 394–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagelund, A.; Kavli, H. If work is out of sight. Activation and citizenship for new refugees. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2009, 19, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindo, R. Struggle for citizenship: Interaction between political society and civil society at a Kurd refugee protest in Tokyo. Citizsh. Stud. 2009, 13, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horst, C. The Depoliticisation of Diasporas from the Horn of Africa: From Refugees to Transnational Aid Workers. Afr. Stud. 2013, 72, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neudorf, E.G. Key Informant Perspectives on the Government of Canada’s Modernized Approach to Immigrant Settlement. Can. Ethn. Stud. 2016, 48, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtonen, K. Resettlement of Middle Eastern Refugees in Finland: The Elusiveness of Integration. J. Refug. Stud. 1998, 11, 38–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtonen, K. The Societal Participation of Vietnamese Refugees: Case Studies in Finland and Canada. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 1999, 25, 469–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fozdar, F. Social cohesion and skilled Muslim refugees in Australia: Employment, social capital and discrimination. J. Sociol. 2012, 48, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, R. The economic adaptation of Vietnamese refugees in Alberta: 1979–84. Migr. World 1987, 15, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, R.L.; Carroll-seguin, R. Labor force participation, household composition and sponsorship among Southeast Asian refugees. Int. Migr. Rev. 1986, 20, 381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, Y.; Poole, C.; Mollica, R.F.; Frankel, M. Relationship of child loss to psychiatric and functional impairment in resettled Cambodian refugees. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1998, 186, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaliu, A.; Thurston, W.E. Identifying best practices of community participation in providing services to refugee survivors of torture: A case description. J. Immigr. Health 2003, 5, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, S. Standing Up for Their Rights: Sri Lankan Tamils and Black-Caribbean Peoples in Toronto. Wadabagei 2004, 7, 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, R. Refugees in Papua New Guinea: Government response and assistance, 1984–1988. Int. Migr. Rev. 1992, 26, 843–876. [Google Scholar]

- Thanh Van, T. Ethnic community supports and psychological well-being of Vietnamese refugees. Int. Migr. Rev. 1987, 21, 833–844. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-García, Ó.F. Gender equality, community divisions, and autonomy: The Prospera conditional cash transfer program in Chiapas, Mexico. Curr. Sociol. 2016, 64, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, M.M.; Callahan, J.L.; Moyer, D.N.; Connally, M.L.; Holtz, P.M.; Janis, B.M. Nepali Bhutanese refugees reap support through community gardening. Int. Perspect. Psychol. Res. Pract. Consult. 2017, 6, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, J. New insights into family learning for refugees: Bonding, bridging and building transcultural capital. Literacy 2011, 45, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, K. “The beat will make you be courage”: The role of a secondary school music program in supporting young refugees and newly arrived immigrants in Australia. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 2012, 34, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, J.; Sulewski, D.; Moreno, J. Adapting community mediation for colombian forced migrants in ecuador. Confl. Resolut. Q. 2017, 34, 409–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, L. Developing social inclusion through after-school homework tutoring: A study of African refugee students in greater Western Sydney. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2009, 30, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earnest, J.; Mansi, R.; Bayati, S.; Earnest, J.A.; Thompson, S.C. Resettlement experiences and resilience in refugee youth in Perth, Western Australia. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.M.; Aguilar, R. Community Social Support for Cuban Refugees in Texas. Qual. Health Res. 2007, 17, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandy, J.; Pe-Pua, R. Beyond mutual acculturation: Intergroup relations among immigrants, Anglo-Australians, and indigenous Australians. Z. Fur. Psychol. 2013, 221, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R. Young caregiving and HIV in the UK: Caring relationships and mobilities in African migrant families. Popul. Space Place 2011, 17, 338–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, S. The determinants of Lebanese attitudes toward Palestinian resettlement: An analysis of survey data. Peace Confl. Stud. 2002, 9, 95–119. [Google Scholar]

- Aylesworth, L.S.; Ossorio, P.G. Refugees: Cultural displacement and its effects. Adv. Descr. Psychol. 1983, 3, 45–93. [Google Scholar]

- Yelland, J.; Riggs, E.; Wahidi, S.; Fouladi, F.; Casey, S.; Szwarc, J.; Duell-Piening, P.; Chesters, D.; Brown, S. How do Australian maternity and early childhood health services identify and respond to the settlement experience and social context of refugee background families? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, J.N.; Johnson-Agbakwu, C.E.; Davis, O.I.; Shipp, M.P. Providers’ perceptions of challenges in obstetrical care for somali women. Obs. Gynecol. Int. 2013, 2013, 149640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conviser, R. Catalyzing system changes to make HIV care more accessible. J. Health Care Poor Underserv. 2007, 18, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, I.H.; Wahidi, S.; Vasi, S.; Samuel, S. Importance of community engagement in primary health care: The case of Afghan refugees. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2015, 21, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejic, V.; Alvarado, A.E.; Hess, R.S.; Groark, S. Community-based interventions with refugee families using a family systems approach. Fam. J. 2017, 25, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worabo, H.J. A Life Course Theory Approach to Understanding Eritrean Refugees’ Perceptions of Preventive Health Care in the United States. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 38, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, T.; Lipson, J.G. Finding a Way: Afghan Women’s Experience in Community Participation. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2004, 15, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, E.; Yelland, J.; Szwarc, J.; Casey, S.; Chesters, D.; Duell-Piening, P.; Wahidi, S.; Fouladi, F.; Brown, S. Promoting the inclusion of Afghan women and men in research: Reflections from research and community partners involved in implementing a ‘proof of concept’ project. Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitch, P.; Rack, P. Mental illness among Polish and Russian refugees in Bradford. Br. J. Psychiatry 1980, 137, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ali, N.; Black, R.; Koser, K. Refugees and Transnationalism: The Experience of Bosnians and Eritreans in Europe. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2001, 27, 615–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemraad, I. The Limits of de Tocqueville: How Government Facilitates Organisational Capacity in Newcomer Communities. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2005, 31, 865–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casier, M. Turkey’s Kurds and the Quest for Recognition. Ethnicities 2010, 10, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casier, M. Neglected middle men? Gatekeepers in homeland politics. Case: Flemish nationalists’ receptivity to the plight of Turkey’s Kurds. Soc. Identities 2011, 17, 501–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.S.; Lee, J.S. Why Do Immigrants and Refugees Give Back to Their Communities and What can We Learn from Their Civic Engagement? Voluntas 2016, 27, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, N. “God must have been sleeping”: Faith as an obstacle and a resource for Rwandan genocide survivors in the United States. J. Sci. Study Relig. 2012, 51, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, J. The Urban Ethnic Community and Collective Action: Politics, Protest, and Civic Engagement by Hmong Americans in Minneapolis-St. Paul. City Community 2014, 13, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhoul, J.; Nakkash, R. Understanding youth: Using qualitative methods to verify quantitative community indicators. Health Promot. Pract. 2009, 10, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilli, L. Disengagement from politics: Nationalism, political identity, and the everyday in a Palestinian refugee camp in Jordan. Crit. Anthropol. 2014, 34, 234–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, E.; McGrath, R. Promoting physical activity among children and youth in disadvantaged South Australian CALD communities through alternative community sport opportunities. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2016, 27, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, H.O.; Kim, Y.S. North Korean women defectors in South Korea and their political participation. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. IJIR 2016, 55, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostergaard-Nielsen, E.K. Transnational Political Practices and the Receiving State: Turks and Kurds in Germany and the Netherlands. Glob. Netw. 2001, 1, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivetti, P. Empowerment without Emancipation: Performativity and Political Activism among Iranian Refugees in Italy and Turkey. Alternatives 2013, 38, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, A. Shadows of War and Holocaust: Jews, German Jews, and the Sixties in the United States, Reflections and Memories. J. Mod. Jew. Stud. 2014, 13, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, J. Schooling and settlement: Refugee education in Australia. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 2008, 18, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggert, L.K.; Blood-Siegfried, J.; Champagne, M.; Al-Jumaily, M.; Biederman, D.J. Coalition Building for Health: A Community Garden Pilot Project with Apartment Dwelling Refugees. J. Community Health Nurs. 2015, 32, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteford, G. Artistry of the everyday: Connection, continuity and context. J. Occup. Sci. 2007, 14, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, J.A.C.; Iwasaki, Y. The role of leisure pursuits in adaptation processes among Afghan refugees who have immigrated to Winnipeg, Canada. Leis. Stud. 2009, 28, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIPEX. How Countries are Promoting Integration of Immigrants. Available online: http://www.mipex.eu/ (accessed on 5 August 2019).

- European Parliament. Migration and Asylum. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/policies/migration-and-asylum_en (accessed on 5 August 2019).

- Giddens, A. The Constitution of Society; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, M.S. Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gusterson, H. From Brexit to Trump: Anthropology and the rise of nationalist populism. Am. Ethnol. 2017, 44, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, H.M.; Stoltz, P.; Willig, R. Recognition, Redistribution and Representation in Capitalist Global Society: An Interview with Nancy Fraser. Acta Sociol. 2004, 47, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgesson, M.; Wang, M.; Niederkrotenthaler, T.; Saboonchi, F.; Mittendorfer-Rutz, E. Labour market marginalisation among refugees from different countries of birth: A prospective cohort study on refugees to Sweden. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2019, 73, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velentgas, P.; Dreyer, N.A.; Nourjah, P.; Smith, S.R.; Torchia, M.M. Developing a Protocol for Observational Comparative Effectiveness Research: A User’s Guide; Government Printing Office: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013.

| First Author, Year | Country of Origin and Host Country (n) | Social Participation Domain | Mental Health Domain | Method Used for Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khawaja, 2006 [19] | Origin: Palestinians Host: Jordan (n) 1615 | Community organized groups: Ethnic communities | Psychological distress and Psychological well-being | Survey |

| Brown, 2011 [32] | Origin: Liberia Host: USA (n) 25 | Regulatory frameworks, conditions and initiatives: Legal status AND Established societal organizations: Financial transactions | Psychosocial well-being | Participant observation |

| Da Lomba, 2010 [33] | Origin: not spec. Host: Great Britain (n) not spec. | Regulatory frameworks, conditions and initiatives: Legal status and Reception systems AND Established societal organizations: Education | - | Document analysis |

| Korac, 2003 [34] | Origin: Former Yugoslavia Host: Italy; Netherlands (comparison) (n) 60 | Regulatory frameworks, conditions and initiatives: Legal status and Reception systems AND Established societal organizations: Financial transactions | Psychosocial well-being and Psychological distress | Interviews |

| Stewart, 2014 [35] | Origin: various nationalities, 23 in total Host: Scotland (n) 30 | Regulatory frameworks, conditions and initiatives: Legal status AND Established societal organizations: Financial transactions and Labor market and Education | Psychological distress | Interviews. |

| Baban, 2016 [36] | Origin: Syria Host: Turkey (n) 30 | Regulatory frameworks, conditions and initiatives: Legal status AND Established societal organizations: Labor market and Financial transactions and Education and Healthcare | - | Interviews and participant observation |

| Ingvarsson, 2016 [37] | Origin: Afghanistan, Iran and Iraq Host: Iceland (n) 9 | Regulatory frameworks, conditions and initiatives: Legal status and Reception systems AND Established societal organizations: Labor market; Financial transactions AND Community organized groups: Sports and leisure | Psychosocial well-being and Psychological distress | Semi-structured interviews |

| Ricento, 2013 [38] | Origin: Colombia Host: Canada (n) 1 | Regulatory frameworks, conditions and initiatives: Reception systems AND Established societal organizations: Labor market and Education | Psychological distress and Psychosocial well-being | Interview, case study |

| Stewart, 2015 [39] | Origin: Sudan and Zimbabwe Host: Canada (n) 85 | Regulatory frameworks, conditions and initiatives: Reception systems | Psychological distress | In-depth interviews |

| Hynes, 2009 [40] | Origin: not spec. (15 countries) Host: Great Britain (n) 48 | Regulatory frameworks, conditions and initiatives: Reception systems | Psychological distress | Interviews and focus group discussions |

| Barnes, 2001 [41] | Origin: Vietnam Host: Australia (n) 14 | Regulatory frameworks, conditions and initiatives: Legal status and Reception systems AND Established societal organizations: Education | Psychosocial well-being | Semi-structured interviews |

| Hagelund, 2009 [42] | Origin: not spec. Host: Norway (n) 344 | Regulatory frameworks, conditions and initiatives: Reception systems AND Established societal organizations: Labor market | - | Survey and in-depth interviews |

| Shindo, 2009 [43] | Origin: Kurdish, country not spec. Host: Japan (n) not spec. | Regulatory frameworks, conditions and initiatives: Individual impact | - | Descriptive case study |

| Horst, 2013 [44] | Origin: African horn (Kenya) Host: Europe (Norway) (n) not spec. | Regulatory frameworks, conditions and initiatives: Conditions for political engagement AND Community organized groups: Political associations | - | Semi-structured interviews |

| Neudorf, 2016 [45] | Origin: not spec. Host: Canada (n) 12 | Established societal organizations: Labor market | - | Semi-structured interviews |

| Valtonen, 1998 [46] | Origin: Iran, Iraq and Kuwait Host: Finland (n) 29 | Established societal organizations: Labor market | - | Semi-structured interviews |

| Valtonen, 1999 [47] | Origin: Vietnam Host: Finland and Canada (n) 45 | Regulatory frameworks, conditions and initiatives: Reception systems AND Established societal organizations: Labor market AND Community organized groups: Ethnic communities and Religious congregations | - | Semi-structured interviews and participant observation |

| Fozdar, 2011 [48] | Origin: Former Yugoslavia (mainly Bosnians), Middle East (mainly Iraqis) and Africa (mainly Somalis and Ethiopians) Host: Australia (n) 150 | Established societal organizations: Labor market | Psychosocial well-being and Psychological well-being | Semi-structured interviews and survey with structured interviews |

| Montgomery, 1987 [49] | Origin: Vietnamese Host: Canada (n) 537 | Established societal organizations: Labor market and Financial transactions | - | Survey |

| Bach, 1986 [50] | Origin: South-East Asia Host: USA (n) 1500 | Established societal organizations: Labor market | - | Structured telephone interviews |

| Caspi, 1998 [51] | Origin: Cambodja Host: USA (n) 161 | Established societal organizations: Labor market AND Community organized groups: Religious congregations | Psychological distress and Psychiatric disorders | Interviews and survey |

| Ramaliu, 2003 [52] | Origin: not spec. Host: Canada (n) not spec. | Established societal organizations: Financial transactions and Labor market and Healthcare | Psychological distress | Document analysis |

| Abraham, 2004 [53] | Origin Sri Lanka (Tamil) and Caribbean Host: Canada(n) not spec | Established societal organizations: Financial transactions AND Community organized groups: Ethnic communities and Sports and leisure | - | Unstructured interviews, literature |

| Preston, 1992 [54] | Origin: Melanesia, Iran Jaya/Indonesia—Melanesia Western Papua Host: Papa New Guinea (n) not spec. | Established societal organizations: Healthcare and Financial transactions | - | Interviews and document analysis |

| Thanh Van, 1987 [55] | Origin: Vietnam Host: USA (n) 160 | Established societal organizations: Financial transactions and Education AND Community organized groups: Ethnic communities | Psychosocial well-being and Psychological well-being | Survey |

| Gil-Garcia Ó, 2016 [56] | Origin: Guatemala Host: Mexico (n) 148 | Established societal organizations: Financial transactions | - | Participant observation, structured and semi-structured interviews |

| Gerber, 2017 [57] | Origin: Nepal (Bhutanese) Host: USA (n) 50 | Established societal organizations: Education and Healthcare | Psychological distress and Psychosocial well-being | Semi-structured interviews and quantitative data |

| Hope, 2011 [58] | Origin: not spec. - broad Host: Great Britain (n) not spec. | Established societal organizations: Education AND Community organized groups: Ethnic communities | Psychosocial well-being and Psychological well-being | Participant observation and interviews |

| Marsh, 2012 [59] | Origin: Sierra Leone, Ghana, Croatia, Vietnam and Pakistan Host: Australia (n) not spec. | Established societal organizations: Education AND Community organized groups: Sports and leisure | Psychological well-being | Interviews, focus group discussions and field work |

| Pugh, 2017 [60] | Origin: Colombia Host: Ecuador (n) not spec. | Established societal organizations: Education AND Community organized groups: Religious congregations and Sports and leisure | - | Case study, document analysis |

| Naidoo, 2009 [61] | Origin: African countries (only spec., Sudan) (n) 37 | Established societal organizations: Education | - | Focus group and semi-structured interviews |

| Earnest, 2015 [62] | Origin: Afghanistan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Sudan, South Sudan, Iraq, Pakistan and Burma Host: Australia (n) not spec. | Established societal organizations: Education and Healthcare AND Community organized groups: Religious congregations and Sports and leisure | Psychosocial well-being and Psychological distress | Individual and focus group interviews and document analysis |

| Barnes, 2007 [63] | Origin: Cuba Host: USA (n) 20 | Established societal organizations: Education and Healthcare AND Community organized groups: Ethnic communities and Religious congregations | Psychosocial well-being | Semi-structured interviews |

| Dandy, 2013 [64] | Origin: Sudan, Afghanistan, Philippines, Bhutan, Burma, Vietnam, Iraq, Iran, Egypt, (England?) Host: Australia (n) 54 | Regulatory frameworks, conditions and initiatives: Reception systems AND Established societal organizations: Education AND Community organized groups: Ethnic communities andSports and leisure | - | Individual and focus group interviews |

| Evans, 2011 [65] | Origin: Africa Host: England (n) 37 | Established societal organizations: Education and Healthcare | Psychological distress | Semi-structured interviews |

| Haddad, 2002 [66] | Origin: Palestinians Host: Lebanon (n) 1073 | Established societal organizations: Education | - | Survey |

| Aylesworth, 1983 [67] | Origin: Indochina, Vietnam, Laos or Hmong, Kambodja Host: USA (n) 217 | Established societal organizations: Healthcare | Psychological distress | Survey with structured interviews |

| Yelland, 2014 [68] | Origin: Afghanistan Host: Australia (n) not spec. | Established societal organizations: Healthcare | Psychological distress and Psychosocial well-being | Interviews |

| Lazar, 2013 [69] | Origin: Somalians (patients, not interviewed) Host: USA, Ohio (n) 14 | Established societal organizations: Healthcare | - | Semi-structured interviews |

| Conviser, 2007 [70] | Origin: Back, Latino, born in Africa Host: USA (n) not spec. | Established societal organizations: Healthcare | - | Interviews and participant observation |

| Cheng, 2015 [71] | Origin: Afghanistan Host: Australia (n) not spec. | Established societal organizations: Healthcare | - | Document analysis and expert statement |

| Pejic, 2017 [72] | Origin: Somalia Host: USA (n) 1 | Established societal organizations: Healthcare | Psychological distress | Case study |

| Worabo, 2017 [73] | Origin: Eritrea Host: USA (n) 15 | Established societal organizations: Healthcare | Psychological distress and Psychological well-being and Psychosocial well-being | Focus group interviews (secondary data) |

| Lindgren, 2004 [74] | Origin: Afghans Host: USA, California (n) 5 | Established societal organizations: Healthcare | Psychological well-being | Semi-structured interviews |

| Riggs, 2015 [75] | Origin: Afghanistan Host: Australia (n) 30 | Established societal organizations: Healthcare | Psychological distress and Psychosocial well-being | Interviews |

| Hitch, 1980 [76] | Origin: Polish, Ukraine and Russian (n) 1164 | Established societal organizations: Healthcare | Psychiatric disorders | Healthcare data |

| Al-Ali, 2001 [77] | Origin: Indochina, Vietnam, Laos or Hmong, Kambodja Host: USA (n) 217 | Community organized groups: Ethnic communities | - | Participant observation and semi-structured interviews |

| Bloemraad, 2005 [78] | Origin: Vietnam and Portuguese (Azorean) Host: USA and Canada (n) 147 | Established societal organizations: Financial transactions AND Community organized groups: Ethnic communities and Religious congregations | - | Interviews and document analysis |

| Casier, 2010 [79] | Origin: Kurdish Host: Belgium and Turkey, EU (n) not spec. | Community organized groups: Ethnic communities and Political associations | - | Participant observation and semi-structured interviews |

| Casier, 2011 [80] | Origin: Turkey (Kurdish) Host: Belgium (n) not spec. | Community organized groups: Ethnic communities and Political associations | - | Semi-structured interviews |

| Weng, 2016 [81] | Origin: Asia, Africa, Caribbean, majority from Sudan Host: USA (n) 54 | Community organized groups: Ethnic communities | - | Semi-structured interviews |

| Fox, 2012 [82] | Origin: Rwanda Host: USA (n) 14 | Community organized groups: Religious congregations | Psychosocial well-being and Psychological well-being | Semi-structured interviews |

| Hein, 2014 [83] | Origin: Laos (Hmong) Host: USA | Community organized groups: Ethnic communities | - | Interviews |

| Makhoul, 2009 [84] | Origin: Palestinians Host: Lebanon (n) 1335 | Community organized groups: Sports and leisure | Psychological distress and Psychiatric disorders and Psychological well-being | Survey and focus group interviews |

| Achilli, 2014 [85] | Origin: Palestinian Host: Jordan (n) not spec. | Community organized groups: Sports and leisure and Political associations | - | Participant observation, semi- and unstructured interviews |

| Rosso, 2016 [86] | Origin: various Host: Australia (n) 152 | Community organized groups: Sports and leisure | - | Survey and semi-structured interviews |

| Jeong, 2016 [87] | Origin: North Korea Host: South Korea (n)151 | Community organized groups: Political associations | - | Survey |

| Østergaard-Nielsen, 2001 [88] | Origin: Turkey(/Kurdistan) Host: Germany and Netherlands (n) not spec. | Community organized groups: Ethnic communities and Political associations | - | Document analysis |

| Rivetti, 2013 [89] | Origin: Iran Host: Italy and Turkey (n) 52 | Community organized groups: Political associations | - | Participant observation and semi-structured interviews |

| Grossmann, 2014 [90] | Origin: European Judes Host: USA (n) not spec. | Regulatory frameworks, conditions and initiatives | Psychosocial well-being and Psychological well-being | Narrative interviews |

| Matthews, 2008 [91] | Origin: Africa, Middle East Host: Australia (n) not spec. | Established societal organizations: Education | Psychosocial well-being and Psychological well-being | Semi-structured interviews |

| Eggert, 2015 [92] | Origin: not spec. Host: USA (n) not spec. | Established societal organizations: Healthcare | Psychological well-being | Survey, interviews and participant observation |

| Whiteford, 2007 [93] | Origin: Albania Host: Makedonia (n) not spec. | Community organized groups | Psychological distress and Psychological well-being | Refugee camp |

| Stack, 2009 [94] | Origin: Afghanistan Host: Canada (n) 11 | Community organized groups: Sports and leisure | Psychological distress | Semi-structured interviews |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niemi, M.; Manhica, H.; Gunnarsson, D.; Ståhle, G.; Larsson, S.; Saboonchi, F. A Scoping Review and Conceptual Model of Social Participation and Mental Health among Refugees and Asylum Seekers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4027. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16204027

Niemi M, Manhica H, Gunnarsson D, Ståhle G, Larsson S, Saboonchi F. A Scoping Review and Conceptual Model of Social Participation and Mental Health among Refugees and Asylum Seekers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(20):4027. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16204027

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiemi, Maria, Hélio Manhica, David Gunnarsson, Göran Ståhle, Sofia Larsson, and Fredrik Saboonchi. 2019. "A Scoping Review and Conceptual Model of Social Participation and Mental Health among Refugees and Asylum Seekers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 20: 4027. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16204027

APA StyleNiemi, M., Manhica, H., Gunnarsson, D., Ståhle, G., Larsson, S., & Saboonchi, F. (2019). A Scoping Review and Conceptual Model of Social Participation and Mental Health among Refugees and Asylum Seekers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(20), 4027. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16204027