Sauna Yoga Superiorly Improves Flexibility, Strength, and Balance: A Two-Armed Randomized Controlled Trial in Healthy Older Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

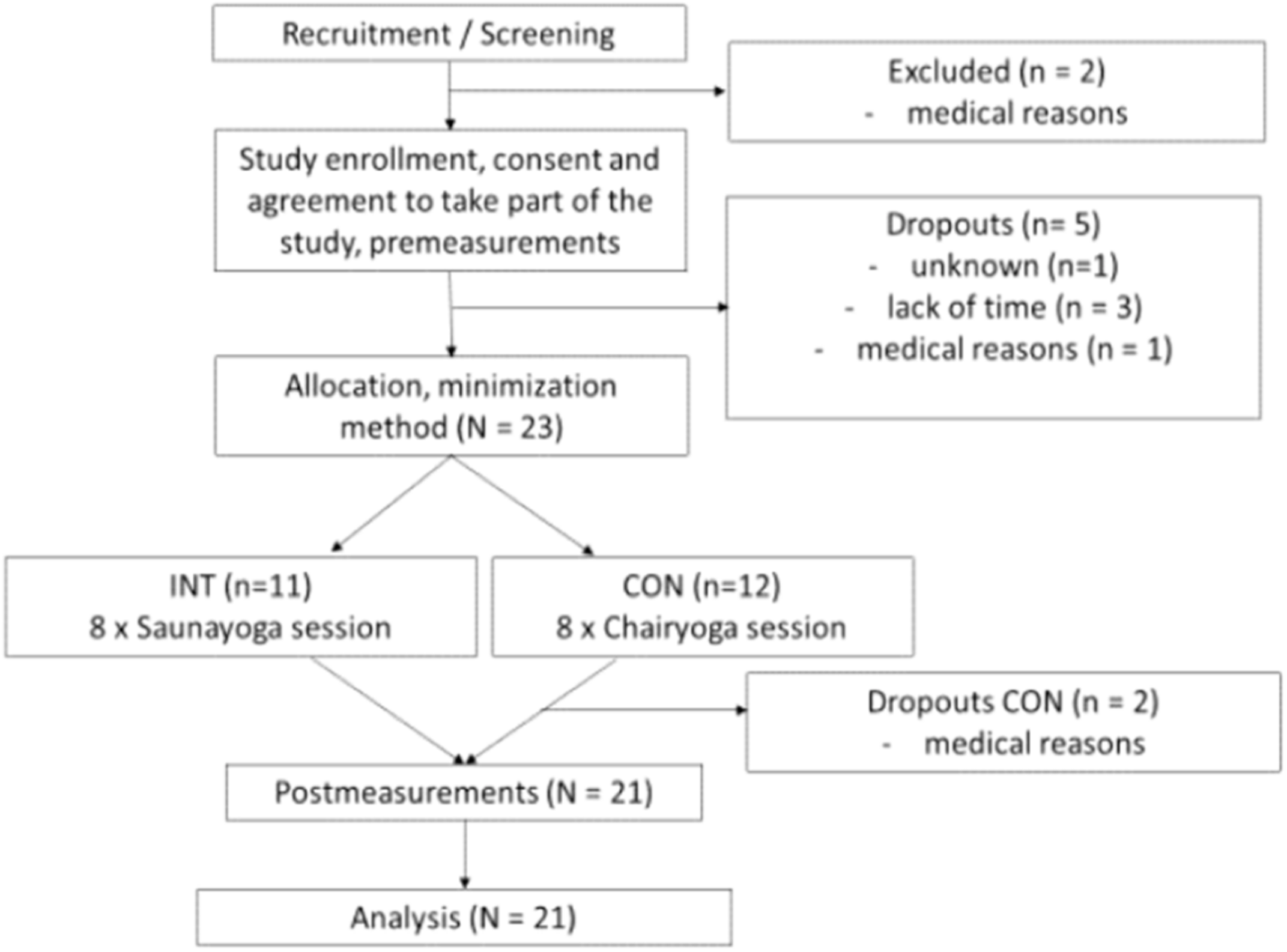

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Intervention

2.3. Testing Procedure

2.4. Anthropometric Data

2.5. Weekly Physical Activity

2.6. Posterior Muscle Chain Flexibility

2.7. Shoulder Flexibility

2.8. Lateral Flexibility of the Spine

2.9. Strength in Lower Extremities

2.10. Static Balance

2.11. Quality of Life

2.12. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Flexibility, Strength, and Balance

3.2. Quality of Life (QoL)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nelson, M.E.; Rejeski, W.J.; Blair, S.N.; Duncan, P.W.; Judge, J.O.; King, A.C.; Macera, C.A.; Castaneda-Sceppa, C. Physical activity and public health in older adults: Recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007, 39, 1435–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noradechanunt, C.; Worsley, A.; Groeller, H. Thai Yoga improves physical function and well-being in older adults: A randomised controlled trial. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, J.N.; Greaves, R.F.; Cohen, M.M. A hot topic for health: Results of the Global Sauna Survey. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 44, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, B.F.; Waring, C.A.; Brashear, T.A. The effects of therapeutic application of heat or cold followed by static stretch on hamstring muscle length. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 1995, 21, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funk, D.; Swank, A.M.; Adams, K.J.; Treolo, D. Efficacy of moist heat pack application over static stretching on hamstring flexibility. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2001, 15, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J.-H.; Lee, S.-O.; Kim, Y.-K. Effects of Thermotherapy Combined with Aromatherapy on Pain, Flexibility, Sleep, and Depression in Elderly Women with Osteoarthritis. J. Muscle Jt. Health 2011, 18, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, P.-C. Rehabilitation training in artificially heated environment. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2017, 13, 546–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Scott, N.W.; McPherson, G.C.; Ramsay, C.R.; Campbell, M.K. The method of minimization for allocation to clinical trials: A review. Control. Clin. Trials 2002, 23, 662–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huy, C.; Schneider, S. Instrument für die Erfassung der physischen Aktivität bei Personen im mittleren und höheren Erwachsenenalter: Entwicklung, Prüfung und Anwendung des “German-PAQ-50+”. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2008, 41, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikli, R.E.; Jones, C.J. Senior Fitness Test Manual; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA; Windsor, ON, Canada; Pudsey, UK; Lower Mitcham, Australia; Torrens Park, New Zealand, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.J.; Rikli, R.E.; Max, J.; Noffal, G. The reliability and validity of a chair sit-and-reach test as a measure of hamstring flexibility in older adults. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 1998, 69, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltaci, G.; Un, N.; Tunay, V.; Besler, A.; Gerçeker, S. Comparison of three different sit and reach tests for measurement of hamstring flexibility in female university students. Br. J. Sports Med. 2003, 37, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesseberg, K.; Bentzen, H.; Ranhoff, A.H.; Engedal, K.; Bergland, A. Physical Fitness in Older People with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2016, 24, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miotto, J.M.; Chodzko-Zajko, W.J.; Reich, J.L.; Supler, M.M. Reliability and Validity of the Fullerton Functional Fitness Test: An Independent Replication Study. J. Aging Phys. Act. 1999, 7, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellin, G.P. Accuracy of measuring lateral flexion of the spine with a tape. Clin. Biomech. 1986, 1, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viitanen, J.V.; Heikkilä, S.; Kokko, M.-L.; Kautiainen, H. Clinical Assessment of Spinal Mobility Measurements in Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Compact Set for Follow-up and Trials? Clin. Rheumatol. 2000, 19, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, M.; Stuckey, S.; Smalley, L.A.; Dorman, G. Reliability of measuring trunk motions in centimeters. Phys. Ther. 1982, 62, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guralnik, J.M.; Simonsick, E.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Glynn, R.J.; Berkman, L.F.; Blazer, D.G.; Scherr, P.A.; Wallace, R.B. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: Association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J. Gerontol. 1994, 49, M85–M94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, A.; Chavis, M.; Watkins, J.; Wilson, T. The five-times-sit-to-stand test: Validity, reliability and detectable change in older females. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2012, 24, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mong, Y.; Teo, T.W.; Ng, S.S. 5-repetition sit-to-stand test in subjects with chronic stroke: Reliability and validity. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010, 91, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchignoni, F.; Tesio, L.; Martino, M.T.; Ricupero, C. Reliability of four simple, quantitative tests of balance and mobility in healthy elderly females. Aging (Milan, Italy) 1998, 10, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohaeri, J.U.; Awadalla, A.W. The reliability and validity of the short version of the WHO Quality of Life Instrument in an Arab general population. Ann. Saudi Med. 2009, 29, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skevington, S.M.; Lotfy, M.; O’Connell, K.A. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2004, 13, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas-Carrasco, R.; Laidlaw, K.; Power, M.J. Suitability of the WHOQOL-BREF and WHOQOL-OLD for Spanish older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2011, 15, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.J. An Effect Size Primer: A Guide for Clinicians and Researchers. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2009, 40, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, L.C.; de Souza Vale, R.G.; Barata, N.J.F.; Varejão, R.V.; Dantas, E.H.M. Flexibility, functional autonomy and quality of life (QoL) in elderly yoga practitioners. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2011, 53, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furtado, G.E.; Uba-Chupel, M.; Carvalho, H.M.; Souza, N.R.; Ferreira, J.P.; Teixeira, A.M. Effects of a chair-yoga exercises on stress hormone levels, daily life activities, falls and physical fitness in institutionalized older adults. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2016, 24, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; McCaffrey, R.; Dunn, D.; Goodman, R. Managing osteoarthritis: Comparisons of chair yoga, Reiki, and education (pilot study). Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2011, 25, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Puymbroeck, M.; Payne, L.L.; Hsieh, P.-C. A phase I feasibility study of yoga on the physical health and coping of informal caregivers. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. ECAM 2007, 4, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-M.; Chen, M.-H.; Hong, S.-M.; Chao, H.-C.; Lin, H.-S.; Li, C.-H. Physical fitness of older adults in senior activity centres after 24-week silver yoga exercises. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 2634–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, A.J.; Clayton, R.H.; Murray, A.; Reed, J.W.; Subhan, M.M.; Ford, G.A. Effects of aerobic exercise training and yoga on the baroreflex in healthy elderly persons. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 27, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, A.A.; van Puymbroeck, M.; Koceja, D.M. Effect of a 12-week yoga intervention on fear of falling and balance in older adults: A pilot study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010, 91, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, S.D.; Dhindsa, M.S.; Cunningham, E.; Tarumi, T.; Alkatan, M.; Nualnim, N.; Tanaka, H. The effect of Bikram yoga on arterial stiffness in young and older adults. J. Altern. Complement. Med. (New York, NY) 2013, 19, 930–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, S.D.; Dhindsa, M.; Cunningham, E.; Tarumi, T.; Alkatan, M.; Tanaka, H. Improvements in glucose tolerance with Bikram Yoga in older obese adults: A pilot study. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2013, 17, 404–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laukkanen, T.; Khan, H.; Zaccardi, F.; Laukkanen, J.A. Association between sauna bathing and fatal cardiovascular and all-cause mortality events. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hariprasad, V.R.; Sivakumar, P.T.; Koparde, V.; Varambally, S.; Thirthalli, J.; Varghese, M.; Basavaraddi, I.V.; Gangadhar, B.N. Effects of yoga intervention on sleep and quality-of-life in elderly: A randomized controlled trial. Indian J. Psychiatry 2013, 55 (Suppl. 3), S364–S368. [Google Scholar]

- Dewhurst, S.; Bampouras, T.M. Intraday reliability and sensitivity of four functional ability tests in older women. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 93, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohannon, R.W.; Larkin, P.A.; Cook, A.C.; Gear, J.; Singer, J. Decrease in timed balance test scores with aging. Phys. Ther. 1984, 64, 1067–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, T.E.; Charpentier, P.A.; Berkman, L.F.; Tinetti, M.E.; Guralnik, J.M.; Albert, M.; Blazer, D.; Rowe, J.W. Predicting changes in physical performance in a high-functioning elderly cohort: MacArthur studies of successful aging. J. Gerontol. 1994, 49, M97–M108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossiter-Fornoff, J.E.; Wolf, S.L.; Wolfson, L.I.; Buchner, D.M. A cross-sectional validation study of the FICSIT common data base static balance measures. Frailty and Injuries: Cooperative Studies of Intervention Techniques. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 1995, 50, M291–M297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, P.; Kiely, D.K.; Leveille, S.G.; Frontera, W.R.; Bean, J.F. Trunk muscle attributes are associated with balance and mobility in older adults: A pilot study. PM R J. Inj. Funct. Rehabil. 2009, 1, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| INT | CON | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (f/m) | 10/1 | 9/1 |

| Age (years) | 68.7 ± 5.9 | 69.3 ± 4.9 |

| Height (cm) | 166.6 ± 7.3 | 169.0 ± 5.1 |

| Weight (kg) | 66.9 ± 9.4 | 67.6 ± 9.0 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 24.3 ± 2.6 | 23.7 ± 2.7 |

| Physical Activity (MET/week) | 199.0 ± 80.9 | 182.0 ± 84.0 |

| Exercise | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | Week 7 | Week 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 min | 1 min | 1 min | 1 min | 1 min | 1 min | 1 min | 1 min |

| 1 | 2 × 3 | 2 × 3 | 2 × 4 | 2 × 4 | 2 × 4 | 2 × 4 | 2 × 4 | 2 × 4 |

| 2 | 2 × 2 | 2 × 2 | 2 × 4 | 2 × 4 | 2 × 4 | 2 × 4 | 2 × 4 | 2 × 4 |

| 3 | 1 × 30 s | 2 × 30 s | 2 × 30 s | 3 × 30 s | 3 × 30 s | 3 × 30 s | 4 × 30 s | 4 × 30 s |

| 4 | 2 × 30 s | 2 × 30 s | 2 × 30 s | 2 × 30 s | 2 × 30 s | 2 × 30 s | 2 × 30 s | 2 × 30 s |

| 5a | 1 × 4 | 2 × 4 | 1 × 4 | 1 × 4 | 1 × 8 | 1 × 8 | 1 × 8 | 1 × 8 |

| 5b | - | - | 1 × 30 s | 2 × 30 s | 3 × 30 s | 3 × 30 s | 3 × 30 s | 3 × 30 s |

| 6 | 1 × 4 | 1 × 4 | 1 × 4 | 1 × 4 | 1 × 4 | 1 × 4 | 1 × 4 | 1 × 4 |

| 0 | 1 min | 1 min | 1 min | 1 min | 1 min | 1 min | 1 min | 1 min |

| INT | CON | GROUP × TIME Interaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | p | ηp2 |

| CSR | 7.86 ± 7.86 | 16.70 ± 9.08 ** | 3.65 ± 15.30 | 7.80 ± 13.60 | 0.028 * | 0.241 |

| BS | −5.34 ± 10.70 | −2.05 ± 5.72 | −4.15 ± 5.69 | −2.90 ± 13.10 | 0.129 | 0.130 |

| LF_R | 44.90 ± 4.54 | 44.60 ± 4.92 | 46.50 ± 6.53 | 45.0 ± 6.46 | 0.379 | 0.043 |

| FL_L | 46.50 ± 4.49 | 44.90 ± 4.57 | 46.10 ± 5.20 | 45.0 ± 4.62 | 0.713 | 0.008 |

| 5STS | 7.26 ± 1.80 | 5.90 ± 1.20 ** | 6.73 ± 1.93 | 6.73 ± 1.93 | 0.061 | 0.181 |

| SR_EC | 14.60 ± 12.40 | 22.0 ± 11.0 * | 5.54 ± 12.40 | 7.80 ± 6.54 | 0.056 | 0.189 |

| INT | CON | GROUP × TIME Interaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QoL | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | p | ηp2 |

| All | 7.55 ± 1.58 | 8.36 ± 1.12 | 8.60 ± 1.07 | 8.80 ± 1.03 | 0.176 | 0.099 |

| PH | 76.30 ± 18.40 | 82.00 ± 11.30 | 83.50 ± 10.03 | 84.60 ± 9.50 | 0.651 | 0.012 |

| PSY | 69.90 ± 11.00 | 75.70 ± 9.78 | 70.60 ± 14.40 | 79.30 ± 10.30 | 0.359 | 0.047 |

| SR | 63.30 ± 13.50 | 72.80 ± 9.02 | 70.60 ± 12.30 | 73.10 ± 11.50 | 0.279 | 0.065 |

| ENV | 80.30 ± 12.00 | 86.00 ± 7.07 * | 85.20 ± 6.91 | 85.10 ± 8.03 | 0.034 * | 0.227 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bucht, H.; Donath, L. Sauna Yoga Superiorly Improves Flexibility, Strength, and Balance: A Two-Armed Randomized Controlled Trial in Healthy Older Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3721. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193721

Bucht H, Donath L. Sauna Yoga Superiorly Improves Flexibility, Strength, and Balance: A Two-Armed Randomized Controlled Trial in Healthy Older Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(19):3721. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193721

Chicago/Turabian StyleBucht, Heidi, and Lars Donath. 2019. "Sauna Yoga Superiorly Improves Flexibility, Strength, and Balance: A Two-Armed Randomized Controlled Trial in Healthy Older Adults" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 19: 3721. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193721

APA StyleBucht, H., & Donath, L. (2019). Sauna Yoga Superiorly Improves Flexibility, Strength, and Balance: A Two-Armed Randomized Controlled Trial in Healthy Older Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(19), 3721. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193721