1. Introduction

Areas affected by wildfire smoke experience elevated levels of air pollutants, including particulate matter (PM), aromatic hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, aldehydes and a large suite of other volatile organic compounds. These pollutants have each been associated with acute and/or chronic adverse pregnancy outcomes, including fetal malformation, fetal death, and low birth weight [

1,

2], though not necessarily in the context of wildfire smoke. Several studies have been conducted examining the impact of single wildfire smoke events on birth weight in California and Australia [

3,

4], but the aggregate impact of wildfire smoke over a multi-year fire record on adverse birth outcomes has not yet been examined. Chronic maternal exposure to ambient PM and indoor biomass smoke during pregnancy have been linked to decreased infant birth weight. In a study conducted in Connecticut and Massachusetts over six years (from 2000 to 2006), it was concluded that exposure to PM

2.5 (particulate matter smaller than 2.5 μm in aerometric diameter) during pregnancy (over the entire pregnancy) was associated with low birth weight (LBW) and small for gestational age (SGA) [

5]. In a 32-study meta-analysis conducted by Sun et al. [

6] done to determine the association between birth weight and exposure to fine particulate matter (PM

2.5), it was concluded that there was a statistically significant association between birth weight and PM

2.5 exposure over the entire pregnancy (−1.6 g/(μg/m

3) [95% CI = −2.7, −0.5]). From the same meta-analysis, it was also concluded that there was a statistically significant association between PM

2.5 exposure during the entire pregnancy and LBW (OR = 1.009/(μg/m

3) [95% CI = 1.003, 1.015]). The overall conclusions from the meta-analysis was that PM

2.5 exposure during pregnancy was associated with low birth weight, and the late stages of the pregnancy were found to be the most critical periods [

6]. Holstius et al. [

3] showed that after adjusting for infant sex, gestational age at birth, and other factors known to influence birth weight; the exposed infants weighed an average of 6.1 g less at birth than unexposed infants. Infants exposed during the second trimester showed the largest average reduction, at 9.7 g. However, O’Donnell et al. [

4] found that male infants born in the highly fire-affected area weighed significantly more on average than male infants born in areas less impacted by wildfire smoke and male infants born in the same areas during non-fire years. Increases in macrosomic infants contributed to the higher average birth weight. There was no significant effect on the female infant weight or gestational age for either gender. In another comprehensive review and meta-analysis conducted by Sapkota et al. [

7] to determine the association between particulate matter and adverse birth outcomes, it was concluded from 20 studies that there was a significant association between PM

2.5 exposure and risk of pre-term births (combined OR = 1.015/(μg/m

3) (95% CI = 1.014, 1.016)).

Exposure to wildfire smoke has also been linked to many other adverse health outcomes including respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14] A systematic search for studies assessing the association between non-occupational exposure to wildfire smoke and physical health impacts concluded that there is (1) consistent evidence for an association between exposure to wildfire smoke and risk of respiratory outcomes and (2) suggestive evidence for an association between exposure to wildfire smoke and risk of cardiovascular outcomes [

15]. In another systematic review, it was concluded that there was consistent evidence for associations between wildfire smoke exposure and respiratory health effects and increasing evidence to support an association between wildfire smoke exposure and all-cause mortality [

16].

Our work is timely because the area burned by wildfires in the western US and Western Canada has increased in recent decades [

17,

18]. While results vary, there are now many studies predicting worsened summertime air quality from wildfires in the western US as the region continues to warm in response to greenhouse gas emissions [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Colorado is susceptible to increased wildfires locally. As wildfires and populations increase, more people in Colorado will be exposed to smoke. This was confirmed in a study by Lui et al. [

25], in which multiple factors, including wildland-urban interface expansion in the Colorado Front range as well as the changing fire regime, are contributing to wildland-urban interface burn. In addition, given the dominant transport patterns of smoke, increased fire activity in Pacific the Northwest and California will likely increase smoke-exposure in Colorado as well. The state routinely receives smoke from these fire-prone regions [

26,

27]. Understanding the association between the pollutants that are released from the fires and birth outcomes is of great public health importance, given the expected continued increases in population and smoke exposure in the state.

This study aims to characterize the association between wildfire smoke PM2.5 exposure and birth outcomes by trimester. Characterizing this relationship will help public health professionals develop more targeted interventions, such as recommendations and guidelines, aimed at reducing the impact on babies and mothers. Furthermore, and while this is not our primary goal, our results could help generate hypotheses about which cellular or molecular mechanisms are impacted by maternal exposure to ambient air pollution, thereby driving adverse clinical outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population

Birth outcome and individual-level covariate data were extracted from the Colorado Vital Records Registry, maintained by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE). This data set aggregates elements from all birth certificates (the Colorado Standard Certificate of Live Birth) issued in Colorado. The data set was provided to the authors under a data use agreement with CDPHE. This study was deemed not to constitute human research as the data are publicly available, de-identified, and did not involve investigator contact with study subjects. These data were supplied by the Center for Health and Environmental Data, Registries and Vital Statistics Branch, of the CDPHE, which specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations, or conclusions it has not provided. Privacy considerations limited the birth certificate data set to report only the year and month of birth, not the exact birth date. The impact of this temporal uncertainty on exposure characterization is described below.

There were a total of 589,992 birth records, of which 535,895 met the inclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria included singleton births between the years of 2007 and 2015 in Colorado with estimated gestational age between 30 and 42 weeks. Full maternal address was not included in the data set, so exposures were linked to mothers by maternal residence ZIP code. All Colorado ZIP codes had at least one day during the years of the study with a non-zero ambient wildfire smoke PM

2.5 concentration. Therefore, all Colorado ZIP codes with at least one single birth during the study period were included in the analyses. Descriptive summaries of the birth cohort are given in

Table 1.

The primary outcomes of interest in this study were pre-term birth and birth weight. Births with estimated gestational age of 37 weeks or less were categorized as pre-term while births with estimated gestational age greater than 37 weeks were categorized as full-term. Maps of the number of births by ZIP code, the percentage of pre-term births by ZIP code, and the mean birth weight by ZIP code are shown in

Supplemental Figures S1–S3, respectively. While the percentage of pre-term births does not display any visible geographic patterns, ZIP codes at high altitude tend to have lower average birth weights.

Secondary outcomes of interest included gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, assisted ventilation following delivery, low birth weight (LBW), and small for gestational age (SGA). For the gestational diabetes analysis, mothers who had pre-pregnancy diabetes were excluded. Similarly, for the gestational hypertension analysis, mothers who had pre-pregnancy hypertension were excluded. Births with weight below the 10th percentile for the gestational age were considered as small for gestational age. Infants weighing less than 2500 g were categorized as LBW while infants weighing 2500 g or more were categorized as normal birth weight. Summary statistics for all outcomes are given in

Supplemental Table S1.

Due to low incidence and the limited temporal precision in our exposures, we did not study outcomes associated with conception itself, such as chromosomal disorders, or outcomes with narrow developmental windows, such as cleft lip/palate, gastroschisis, or neural tube defects, despite the availability of this data.

Birth certificate covariates considered for potential inclusion in the models included: mother’s education categorized as either less than high-school, high-school, bachelors, or more than bachelor’s degree; graduated index (which provides information on prenatal care as is commonly shortened to ‘gindex’); birth year; birth calendar month; alcohol consumption during pregnancy defined as either yes (drinking during any trimester) or no; smoking during pregnancy defined as either yes (smoking during any trimester) or no; income categorized as <$25,000, $25,000, $49,999, $50,000–$74,999, or $75,000+; asthma defined as either yes or no, and number of prenatal visits categorized as <10 or 10+. We collapsed maternal race/ethnicity into three categories (Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, or non-Hispanic non-White) because the birth certificate allowed for several hundred self-reported race/ethnicity combinations, only a few of which had a substantial number of births. We trichotomized maternal age according to the standard age categories used in obstetrics as indicators of risk (less than 18, 18–35, or greater than 35 years). All the other variables were self-reported or physician-reported on the birth certificate in the categories given.

2.2. Exposure Characterization

Wildfire smoke PM

2.5 and non-smoke PM

2.5 were jointly characterized using a previously published method [

28] that has been used in a prior health study [

29]. This method combines NOAA’s satellite imagery-based Hazard Mapping System [

30,

31,

32] to determine daily smoke plume extent with spatial interpolation of ground-based PM

2.5 monitor values downloaded from the US EPA Air Quality System (AQS). Daily concentrations of both components over a 15 × 15 km grid covering the contiguous US were then matched to ZIP codes using the mean of the concentrations in each grid cell overlapping the ZIP code, weighted by the population in each grid cell and the areal overlap between the grid cell and ZIP code. Monthly time series of total PM

2.5 and wildfire smoke PM

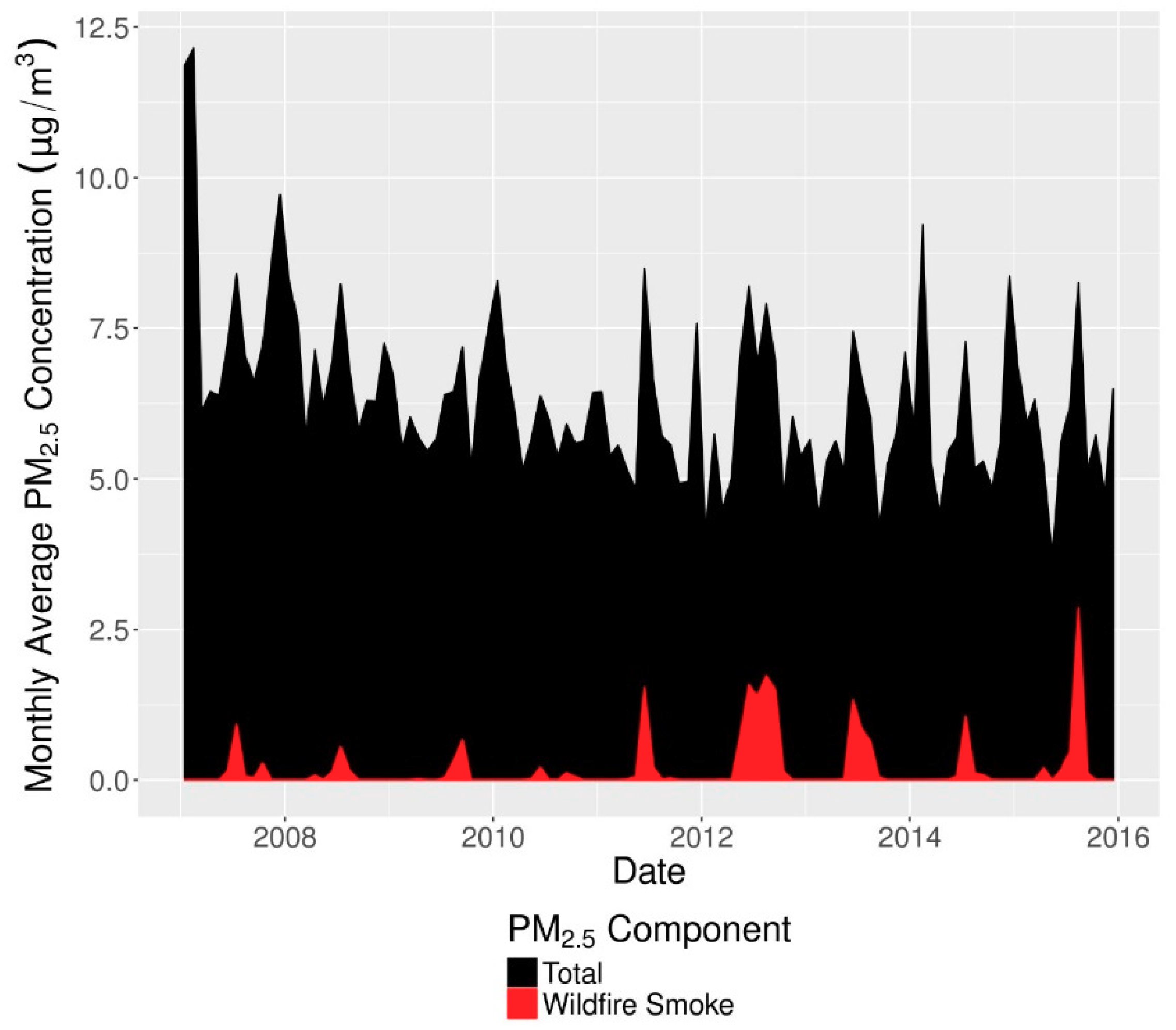

2.5 in Colorado are shown in

Figure 1. Wildfire smoke PM

2.5 concentrations increased both in absolute terms and relative to total PM

2.5, which itself decreased during our study period. In the latter years of the study wildfire smoke became a major contributor to PM

2.5 peaks during summer months.

A map of ZIP code-specific daily wildfire smoke PM

2.5 concentrations averaged over the study period is shown in

Figure 2. The northern portion of the Front Range including Fort Collins experienced the highest wildfire smoke PM

2.5 concentrations in the state. The Denver metropolitan region and the northwest and northeast corners also experienced high concentrations relative to the southern half of the state. A significant fraction of smoke in Colorado comes from smoke transported from the US Pacific Northwest and Western Canada [

26]. A common route for this transported smoke flows around the Rocky Mountains, through the plains of eastern Wyoming into the northern Front Range region of Colorado (the most smoke impacted portions of

Figure 2). From the northern Front Range, the smoke disperses either east or south following topography and wind patterns.

Other exposure covariates included in the statistical models were ambient temperature, PM

10, and ozone. PM

10 was included instead of coarse PM because PM

10 is directly monitored, and not all of the sites with PM

10 monitors also have PM

2.5 monitors, making it difficult to estimate the spatial distribution of coarse PM. However, PM

2.5 is a small contributor to PM

10 mass, and concentrations of the two are not strongly correlated (in our dataset PM

10 has correlations of 0.44, 0.15, and 0.26, respectively, with wildfire smoke PM

2.5, non-smoke PM

2.5, and total PM

2.5). ZIP code-specific daily values of these variables were computed, as in [

29], by taking the median of all reported values from monitors falling within the ZIP code boundary or within 20 km of its centroid. In contrast to the wildfire smoke and non-smoke PM

2.5 exposure characterization above, temperature, PM

10, and ozone values were not spatially interpolated due to concerns about interpolation accuracy given the sparseness of their monitor networks. Because these variables were not interpolated, grid cell population weighting was not performed. A 20 km buffer distance was chosen as the default as a compromise between accuracy and power. A smaller buffer implies more accurate characterization of population exposure, but at the cost of more ZIP codes with missing exposure data and lower power. A larger buffer implies less accurate exposure characterization but fewer ZIP codes with incomplete data and thus higher power. The impact of varying this buffer distance is explored in sensitivity analyses.

Because the calendar month of birth was already included in the gestational outcome models and indirectly accounted for seasonal changes in temperature, the temperature variable was normalized to the time of year by subtracting the monthly mean temperature. This variable is referred to as “Temperature Deviation” in the tables below. Summary statistics for the exposure variables are given in

Table 2.

Because the exact birth date was unavailable and because the gestational age was estimated at a weekly resolution, there was uncertainty regarding the exact start and end dates of each gestation and of individual trimesters. This uncertainty precluded analyzing the gestational period at a more refined temporal resolution than trimester. Indeed, models run using monthly estimates of exposure yielded results that were not robust under sensitivity analysis as a consequence of low exposure accuracy and over-parameterization.

Trimester-specific exposures were calculated as follows. First, our estimate for the earliest conception date was determined by taking the first day of the birth month and subtracting the gestational age in weeks and an additional six days. Our estimate for the latest conception date was determined by taking the last day of the birth month and subtracting the gestational age in weeks. These were then defined as the earliest and latest possible start dates for the first trimester. The earliest end date of the first trimester was calculated by adding 12 weeks to the earliest start date. The latest end date of the first trimester was calculated by adding 12 weeks and six days to the latest start date. The earliest and latest start/end dates for other trimesters were calculated similarly, with the second trimester defined to end at 27 weeks and six days.

Thus, for each trimester, three adjacent intervals were defined: first, between the earliest and latest start date; second, between the latest start and earliest end date; and third, between the earliest and latest end date. Finally, the average exposure over a trimester was calculated by taking a weighted mean of daily ZIP code-resolution values over the days in these three intervals. The values in the second interval (where there is most certainty) were all given a weight of 1, while in the first and third intervals the weights decreased linearly to zero toward the earliest start and latest end date. Thus, the trimester exposure estimates were most strongly influenced by values on days that were most certain to fall in the true trimester interval and less strongly influenced by values on days that were less certain to fall in the true trimester interval.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Characteristics of the cohort were summarized using descriptive statistics to determine if there were any differences between the groups (pre-term versus full-term) in the cohort that might lead to confounding. Means and standard deviations were determined for the continuous variables, and frequency and percentages were determined for the categorical variables for the overall cohort and for the main outcome of interest for pre-term versus full-term births. Multi-collinearity was evaluated between income, education, race/ethnicity, smoking and drinking using the variance inflation factor (VIF). All VIFs were less than 3.4, which is below the standard threshold (VIF > 10) for dropping or combining variables. Therefore, we retained each maternal variable (income, education, race/ethnicity, smoking and drinking) in the models.

For the pre-term birth outcome, logistic regression models were developed to estimate associations between lagged wildfire smoke PM2.5 exposures and pre-term birth. The model included a separate strata (intercept) for each residential ZIP code and accounted for wildfire smoke PM2.5 (three trimesters), ozone (three trimesters), non-wildfire PM2.5 (three trimesters), PM10 (three trimesters), normalized temperature (three trimesters), calendar month of birth, birth year, maternal age, race/ethnicity, education, and income, maternal smoking during pregnancy, maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy, maternal asthma, and gindex.

For continuous birth weight, mixed effects models with a random intercept by ZIP code were used to estimate associations with wildfire smoke PM2.5. This model used the same predictor variables as in the preterm birth models but with additional control for gestational age using a nonlinear spline fit with 5 degrees of freedom.

For the secondary outcomes of interest (NICU, gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, assisted ventilation at time of delivery, SGA, and LBW), logistic models were used to estimate associations with wildfire smoke PM2.5. These secondary models accounted for all confounders accounted for in the preterm birth model as well as a nonlinear control for gestational age as used in the birth weight model. For LBW, infants were categorized into two birth weight categories (low birth weight (<2500 g) or normal birth weight (≥2500 g)).

Estimates of association over the full gestational period were calculated in two ways. First, the mean effect over all three trimesters was computed using the contrast statement in SAS with each trimester effect weighted by 1/3. Second, models were run using full gestation values of the air pollutants and temperature rather than trimester-specific values.

Sensitivity analyses were also conducted to determine if there were any changes in the overall results for the primary outcomes under different data processing and confounder choices. In total. eight sensitivity analyses were performed for each of the two main outcomes: (1) the main model without PM10; (2) the main model without ozone, PM10, or non-wildfire PM2.5; (3) the main model with infant gender included; (4) the main model without temperature; (5) the main model using a 5-km buffer distance; (6) the main model using a 10-km buffer; (7) the main model using a 50-km buffer; and (8) the main model with ZIP code-level wildfire smoke and non-wildfire PM2.5 values computed without population weighting.

All data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA), and an alpha level of 0.05 was used to determine significance in all the statistical tests and confidence intervals. Logistic analyses were performed using PROC Logistic while birth weight was analyzed using PROC hpmixed.

4. Discussion

Exposure to wildfire smoke PM2.5 during the second trimester was positively associated with preterm birth. Specifically, each 1 μg/m3 increase in trimester-average wildfire smoke PM2.5 over the second trimester was associated with a 13.2% increase in the odds of preterm birth. For a woman whose second trimester corresponds to peak wildfire season (June, July, and August) and whose exposure equals the Colorado average for the season (0.548 μg/m3), this translates to a 7.0% increased odds of pre-term birth. This result was robust to changes to the statistical model and the data processing pipeline. Positive associations with preterm birth were also found after averaging the three trimester-specific associations and when modeling exposure over the full gestational period, though the latter result was not consistently replicated in all sensitivity analyses.

Among secondary end points, the maternal outcomes (gestational diabetes and hypertension) were positively associated with wildfire smoke PM2.5, though the strongest results were found when this exposure took place in the first trimester of pregnancy. Each additional μg/m3 increase in trimester average exposure was associated with a 14.4% increase in gestational diabetes and a 14.8% increase in gestational hypertension. However, among infant outcomes, results for SGA and LBW were null or weak, while results for NICU admission and assisted ventilation were contrary to our expectation.

Results for birth weight were similar to Holstius et al. [

3], in which wildfire exposure resulted in decreased birth weight. While Holstius et al. had a larger sample size (n = 886,034) and characterized exposure differently, both studies found a negative association between wildfire smoke exposure and birth weight, though in different trimesters (−5.7 g/(μg/m

3) in the first trimester and -9.7 g in the second trimester for the present work and Holstius et al., respectively). However, the present work used a continuous exposure variable while Holstius et al. dichotomized pregnancies into exposed/not exposed categories based on reports of fires from the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, making comparisons of effect magnitude problematic. Their paper also had different exclusion criteria than our study; they excluded preterm births and post-term births, while we included preterm births after 30 weeks in our analysis.

While no study has directly tested for differences in birth outcome associations between wildfire smoke PM

2.5 and total PM

2.5 or non-smoke PM

2.5, Sun et al. [

6] report a pooled (over 32 studies) estimate for birth weight and total PM

2.5 of −1.59 g/(μg/m

3) (95% CI: −2.68, −0.50) over the full gestation, which is similar to our estimate of −2.0 g/(μg/m

3) for smoke PM

2.5 over the same period. This similarity suggests non-differential impacts on birth weight. However, we found the strongest associations with birth weight in the first trimester while Sun et al. found the opposite, which may reflect the lack of robustness in our birth weight results.

Prior work on criteria air pollutants and birth outcomes has found increases in preterm birth risk and decreases in birth weight with total PM

2.5 and PM

10. Lamichhane et al. [

33] found a 2.2 g/(μg/m

3) decrease in birth weight and a 1.4% (μg/m

3)

−1 increase in preterm birth risk over the entire pregnancy. The former is similar in magnitude to our (non-significant) result, while the latter is lower than the 7.6% (μg/m

3)

−1 increase that we observed. A study in New York City [

34] found a 4.8 g/(μg/m

3) decrease in birth weight with PM

2.5 mass, while NO

2 decreased birth weight by 1.8 g/ppb. Coarse PM has also been found to negatively impact birth weight [

35].

Mechanical assisted ventilation provides crucial breathing support to neonates, but prolonged ventilation is a risk factor for bronchopulmonary dysplasia [

36]. While our finding of a negative association between wildfire smoke exposure and assisted ventilation after delivery is counter to our original hypothesis, there is limited evidence suggesting that maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy can lead to accelerated growth in abdomen diameter [

37] and reduced risk of respiratory distress syndrome [

38]. Thus, there is some support for the theory that adverse pregnancy conditions may lead to accelerated pulmonary maturity. However, a large body of other work has shown detrimental associations between maternal smoking and fetal growth restriction as well as other developmental delays [

39,

40] including reduced lung function in the week after birth [

41,

42] and prenatal lung volume [

43]. Furthermore, individual ambient air pollutants have also been linked to reductions in fetal abdominal circumference during the first and second trimester [

44] and many other adverse pregnancy outcomes [

6,

7,

33,

45].

This study had a number of strengths. First, the study sample was relatively large and therefore there was enough power to be able to detect differences in outcome measures. Second, the study investigated a broader range of gestational outcomes than previous studies. Third, the study assessed the impact of wildfire smoke exposure using a spatially and temporally resolved multi-year wildfire exposure record. Fourth, the birth certificate dataset included many individual-specific variables for the assessment of potential confounding.

This study also has a number of limitations. First, many of birth certificate variables were self-reported by the mother, which may have led to misreporting of some confounding variables (e.g., mother’s education, income, drinking during pregnancy, smoking during pregnancy), making it difficult to control for these variables accurately. Second, ambient exposure may not accurately reflect personal exposure, either because of time spent indoors, the use of area (ZIP code) averages rather than residence-specific estimates of the exposure, or changes in residence address over the course of the pregnancy. Third, while our sample size was relatively large (comparable to Holstius et al.), few pregnant women were exposed to significant wildfire smoke for extended periods of time. That being said, showing detrimental effects even at low exposures underscores the importance of potential interventions. Fourth, the birth certificate data did not contain the specific birth dates, but only month and year of birth, and therefore we could not analyze the data at a daily or weekly resolution because we could not accurately assign exposure. In addition, we were not able to conduct the analysis at a monthly resolution because we found that monthly models yielded non-robust results in sensitivity analyses, which suggested that such models were over-parameterized given the amount of data available. The date imprecision may have led to exposure misclassification as some of the exposure assigned to a particular birth or trimester may have occurred either prior to conception, after the birth occurred, or in a different trimester. However, the present work has attempted to account for such uncertainty by weighting the contributions of daily exposures to the trimester and full gestation averages. Future studies may improve the accuracy of the exposure characterization by using birth date rather than birth month, by acquiring mothers’ prior addresses during pregnancy, or by outfitting volunteers with personal or household monitoring devices. Finally, the health effects we ascribe to the effects of wildfire smoke PM2.5 may not be due to this pollutant alone but may be due in part to other, unmeasured fire-related air pollutants carried in the same plumes, such as NOx and VOCs, which differ from PM2.5 in their health effects and characteristic atmospheric lifetimes. The extent to which wildfire smoke PM2.5 tracks with these other pollutants is an active area of investigation by members of our research team.