Evolution of the Physical and Social Spaces of ‘Village Resettlement Communities’ from the Production of Space Perspective: A Case Study of Qunyi Community in Kunshan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Research Context and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Village Resettlement Community

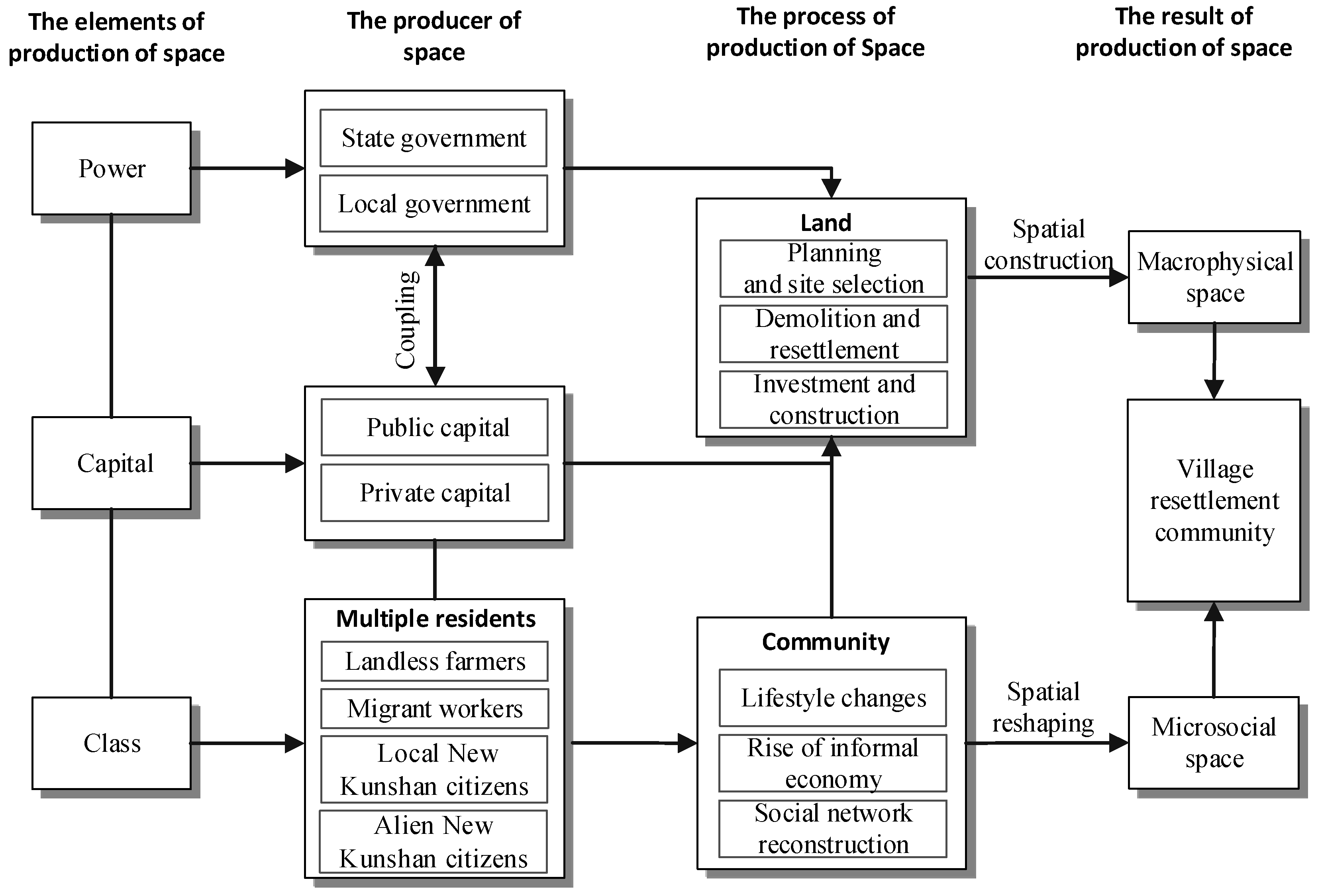

2.2. Theory of the Production of Space

2.3. Conceptual Framework

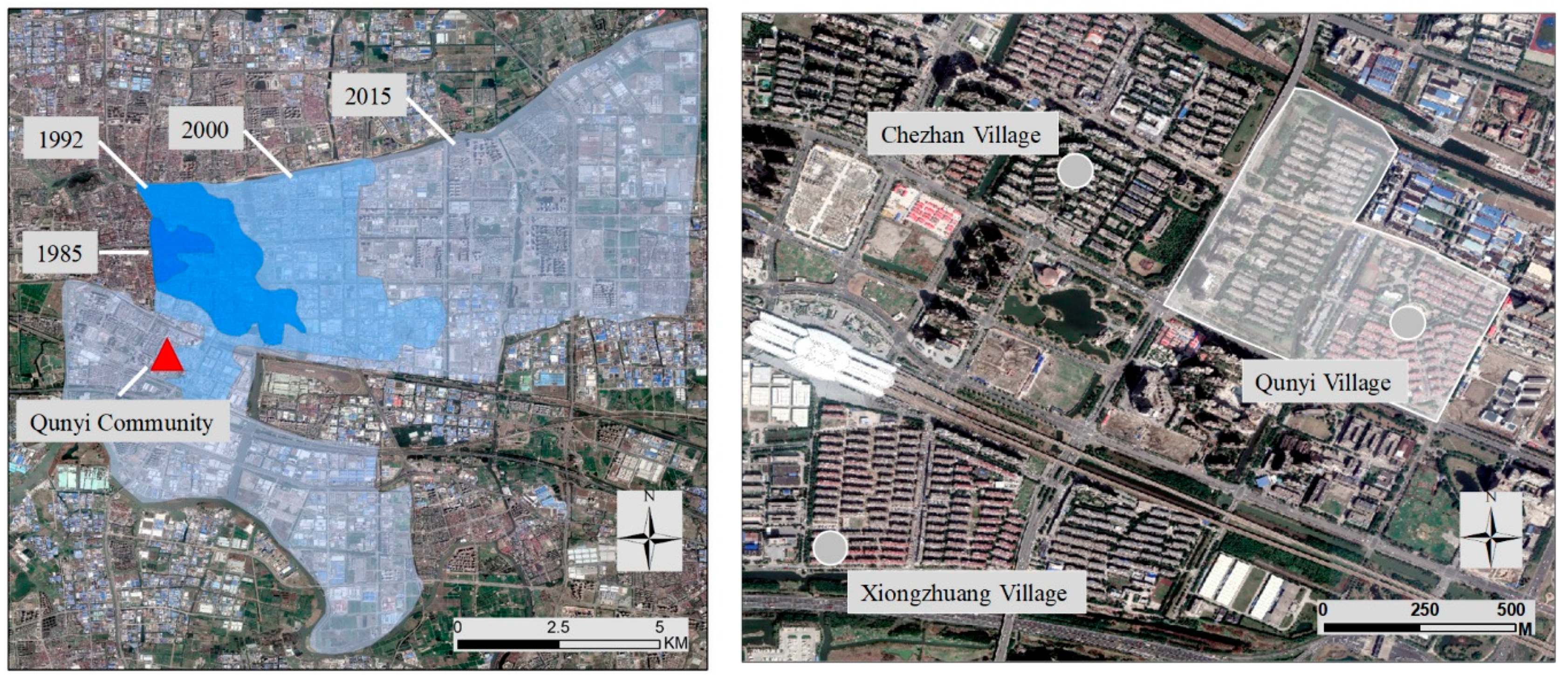

3. Study Area, Data, and Methodology

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Sources and Methodology

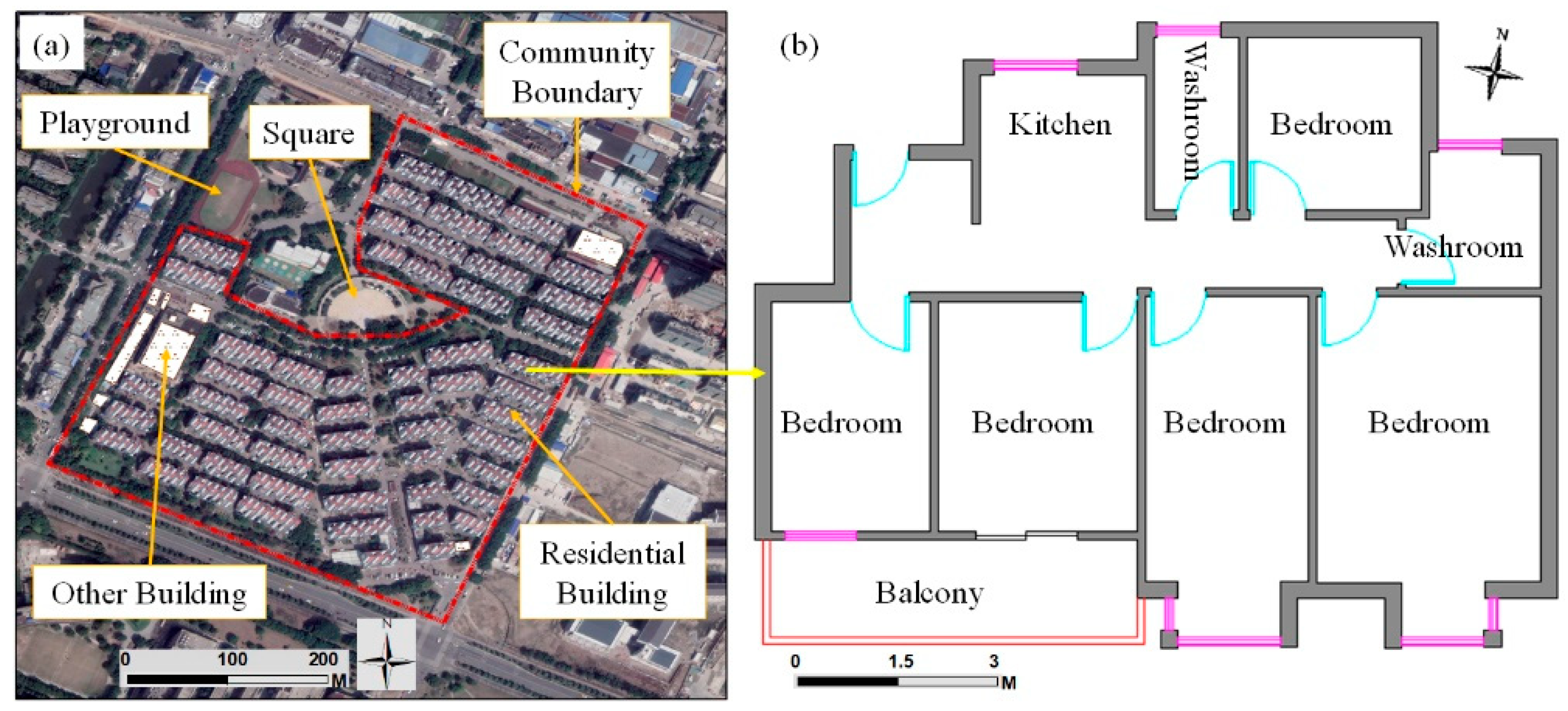

4. Production of Physical Space

4.1. Powerful Propulsion of the Local Government

4.2. Joint Operation of Capital and Power

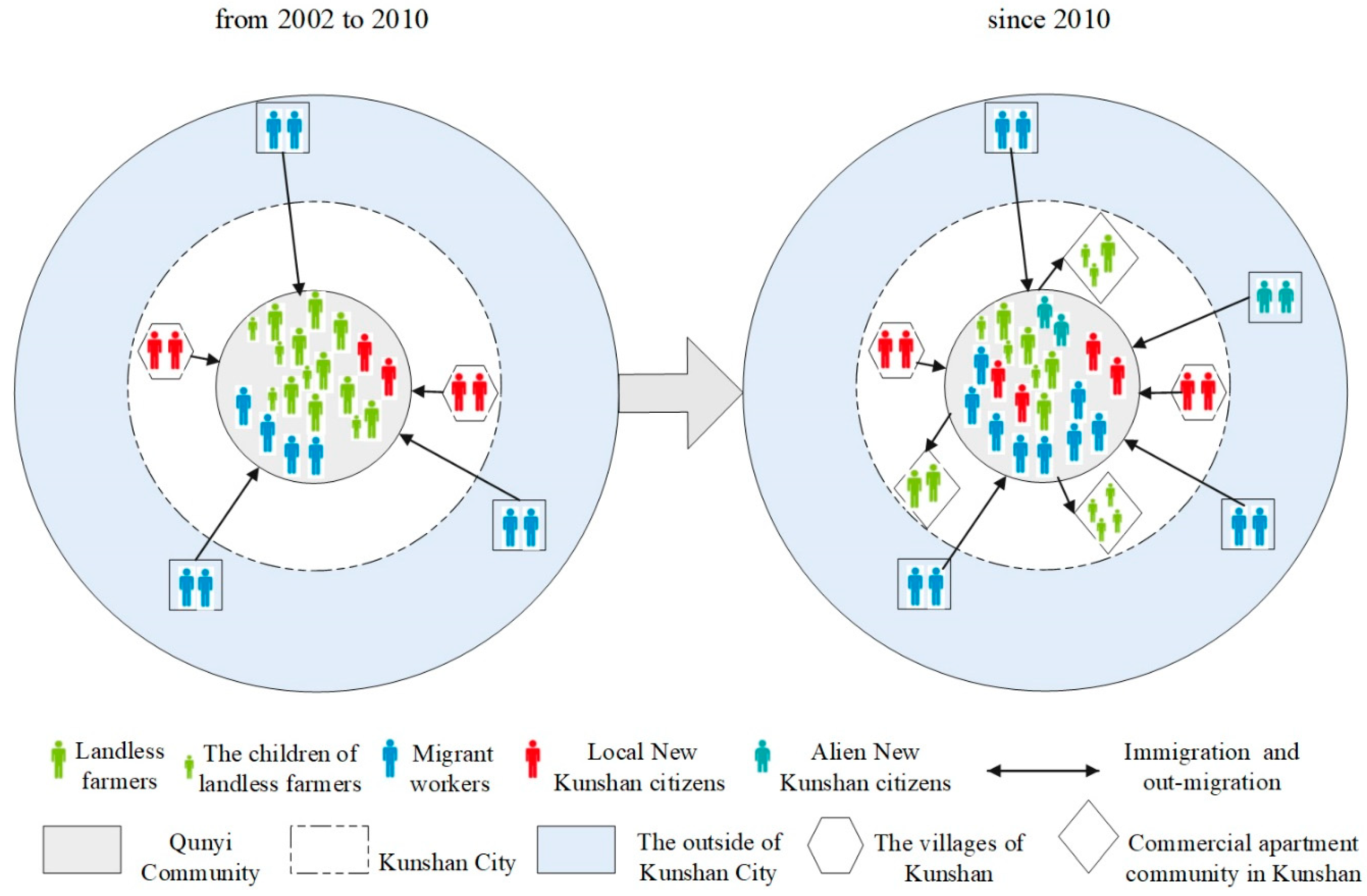

5. Reproduction of Social Space

5.1. The Changing Composition of Community Residents

5.2. Changes in the Social Relationships among Residents

5.2.1. Close Economic Relationship

5.2.2. Well-Defined Social Relationship

5.3. Reproduced Social Space

5.3.1. Living Space

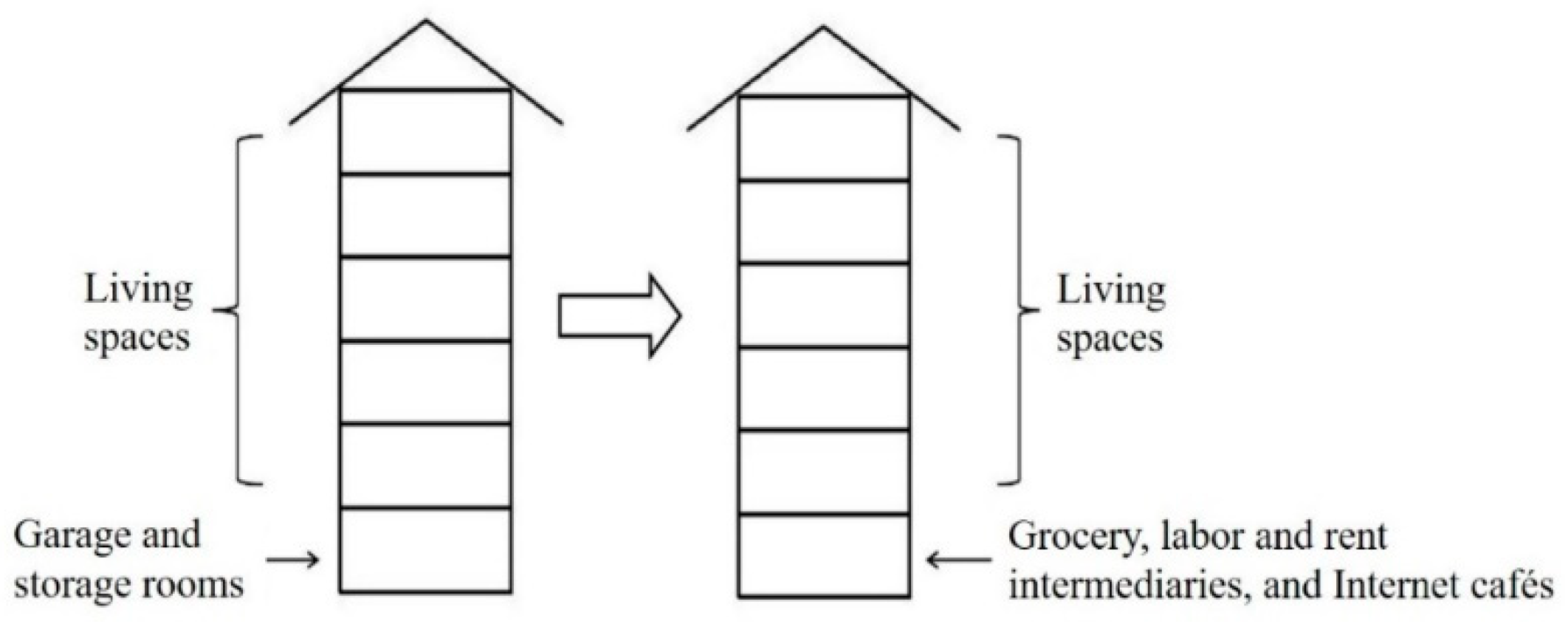

5.3.2. Consumption Space

5.3.3. Communication Space

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, F.; Yeh, A.; Xu, J. Urban Development in Post-Reform China: State, Market, Space; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.J. China’s rapid urbanization. Science 2013, 342, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Hao, P.; Huang, X. Land conversion and urban settlement intentions of the rural population in China: A case study of suburban Nanjing. Habitat Int. 2016, 51, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, W.; Lu, D. Challenges and the way forward in China’s new-type urbanization. Land Use Policy 2016, 55, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, F.; Wuzhati, S.; Wen, B. Urban or village residents? A case study of the spontaneous space transformation of the forced upstairs farmers’ community in Beijing. Habitat Int. 2016, 56, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T. Community features and urban sprawl: The case of the Chicago metropolitan region. Land Use Policy 2001, 18, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, T.; MacDonald, M. Community-supported slum-upgrading: Innovations from Kibera, Nairobi, Kenya. Habitat Int. 2017, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.J.; Liu, Y.T.; Webster, C.; Wu, F.L. Property rights redistribution, entitlement failure and the impoverishment of landless farmers in China. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 1925–1949. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Tang, B.; Chan, E.H.W. State-led land requisition and transformation of rural villages in transitional China. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Li, S.Q. Landless female peasants living in resettlement residential areas in China have poorer quality of life than males: Results from a household study in the Yangtze River Delta Region. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2014, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Hooimeijer, P.; Bolt, G.; Sun, D. Uneven compensation and relocation for displaced residents: The case of Nanjing. Habitat Int. 2015, 47, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, W.; Chen, T.; Li, X. A new style of urbanization in China: Transformation of urban rural communities. Habitat Int. 2016, 55, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lü, B.; Chen, R. Evaluating the life satisfaction of peasants in concentrated residential areas of Nanjing, China: A fuzzy approach. Habitat Int. 2016, 53, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Chen, M.; Chen, R.; Guo, Z. Multi-scalar separations: Land use and production of space in Xianlin, a university town in Nanjing, China. Habitat Int. 2014, 42, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.D. Beyond the Sunan model: Trajectory and underlying factors of development in Kunshan, China. Environ. Plan. A 2002, 34, 1725–1747. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, S.S. Institutional innovations, asymmetric decentralization, and local economic development: A case study of Kunshan, in post-Mao China. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2007, 25, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, S.S. New local state power through administrative restructuring-a case study of post-Mao China county-level urban entrepreneurialism in Kunshan. Geoforum 2013, 46, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, L. Speculative urbanism and the making of university towns in China: A case of Guangzhou University Town. Habitat Int. 2014, 44, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. Spaces of Capital: Towards a Critical Geography; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The Urbanization of Capital; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, C.; Chen, M.; Duan, J.; Yang, D. Uneven development, urbanization and production of space in the middle-scale region based on the case of Jiangsu province, China. Habitat Int. 2017, 66, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E. The socio-spatial dialectic. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1980, 70, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottdiener, M. The Social Production of Urban Space; University of Texas Press: Texas, TX, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The Enigma of Capital and the Crises of Capitalism; Profile Books: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N. Uneven Development: Nature, Capital, and the Production of Space; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Unwin, T. A waste of space? Towards a critique of the social production of space. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2000, 25, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olds, K. Globalization and the production of new urban spaces: Pacific Rim megaprojects in the late 20th century. Environ. Plan. A 1995, 27, 1713–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophers, B. Revisiting the urbanization of capital. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2011, 101, 1347–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. Power/Knowledge; Harvester: Brighton, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Of other spaces. Diacritics 1986, 16, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. The Urban Revolution; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.; Liu, Y.; Wang, F. Production of space in the urban-rural frontier: A case study of Rainbow, a floating population concentrated community in Guangzhou. Hum. Geogr. 2013, 28, 86–91. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Sun, D. The physical space change and social variation in urban village from the perspective of space production: A case study of Jiangdong Village in Nanjing. Hum. Grogr. 2014, 29, 1–6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Qian, Q.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y. The spatial change of TaoBao village in Lirengdong, Guangzhou in the perspective of spatial production. Econ. Geogr. 2016, 36, 120–126. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Quaini, M. Geography and Marxism; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, G. Chinese Urbanism in Question: State, Society, and the Reproduction of Urban Spaces. Urban Geogr. 2007, 28, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z. The production of urban space in globalizing Shanghai. Taiwan Soc. Res. Q. 2004, 3, 61–83. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.; Tang, G.; Li, X.; Heilig, G.K. Socio-economic driving forces of land-use change in Kunshan, the Yangtze River delta economic area of China. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 83, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.T.X. The changing settlements in rural areas under urban pressure in China: Patterns, driving forces and policy implications. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 120, 170–177. [Google Scholar]

| Residents Type | Landless Farmers | Migrant Workers | Local New Kunshan Citizens | Alien New Kunshan Citizens | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sample size | 65 | 73 | 48 | 46 | |

| average age (years old) | 55.3 | 31.2 | 42.1 | 39.8 | |

| length of residency (years) | 14 | 3.2 | 7.9 | 8.4 | |

| marriage (%) | married | 100 | 20.5 | 100 | 91.3 |

| unmarried | 0 | 79.5 | 0 | 8.7 | |

| education level (%) | primary school and below | 20.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| junior high school | 76.9 | 30.1 | 16.7 | 13.0 | |

| senior high school /vocational high school | 3.1 | 64.4 | 75.0 | 73.9 | |

| junior college/ undergraduate and above | 0.0 | 5.5 | 8.3 | 13.0 | |

| occupation (%) | government employee /public servant | 4.6 | 0 | 4.2 | 2.1 |

| enterprise worker | 70.8 | 95.9 | 72.9 | 54.4 | |

| manager/ technical staff | 0 | 4.1 | 10.4 | 21.7 | |

| landlord | 92.3 | 0 | 0 | 4.3 | |

| businessman | 20 | 0 | 12.5 | 17.5 | |

| community manager | 4.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| registration status (%) | local non-agricultural residence | 100 | 0 | 52.1 | 71.7 |

| local agricultural residence | 0 | 0 | 47.9 | 0 | |

| nonlocal registered permanent residence | 0 | 100 | 0 | 28.3 | |

| housing or renting area (%) | below 90 m2 | 30.8 | 0 | 16.7 | 89.1 |

| above 90m2 | 69.2 | 0 | 83.3 | 10.9 | |

| below 10 | 0 | 63.1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 10 m2–20 m2 | 0 | 23.3 | 0 | 0 | |

| above 20 m2 | 0 | 13.6 | 0 | 0 | |

| Residents | Landless Farmers | Migrant Workers | Local New Kunshan Citizens | Alien New Kunshan Citizens | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sample size | 65 | 73 | 48 | 46 | |

| associate with (%) | relatives | 100.0 | 16.4 | 100.0 | 17.4 |

| neighbors | 35.4 | 12.3 | 8.3 | 2.2 | |

| friends | 66.2 | 86.3 | 77.1 | 65.2 | |

| co-worker | 18.5 | 91.8 | 27.1 | 41.3 | |

| fellow villagers | 58.5 | 98.6 | 18.8 | 19.6 | |

| others | 9.2 | 2.7 | 6.3 | 4.3 | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, L.; Xiong, L. Evolution of the Physical and Social Spaces of ‘Village Resettlement Communities’ from the Production of Space Perspective: A Case Study of Qunyi Community in Kunshan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2980. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16162980

Zhou L, Xiong L. Evolution of the Physical and Social Spaces of ‘Village Resettlement Communities’ from the Production of Space Perspective: A Case Study of Qunyi Community in Kunshan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(16):2980. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16162980

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Lei, and Liyang Xiong. 2019. "Evolution of the Physical and Social Spaces of ‘Village Resettlement Communities’ from the Production of Space Perspective: A Case Study of Qunyi Community in Kunshan" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 16: 2980. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16162980

APA StyleZhou, L., & Xiong, L. (2019). Evolution of the Physical and Social Spaces of ‘Village Resettlement Communities’ from the Production of Space Perspective: A Case Study of Qunyi Community in Kunshan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(16), 2980. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16162980