LGBTIQ+ Homelessness: A Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

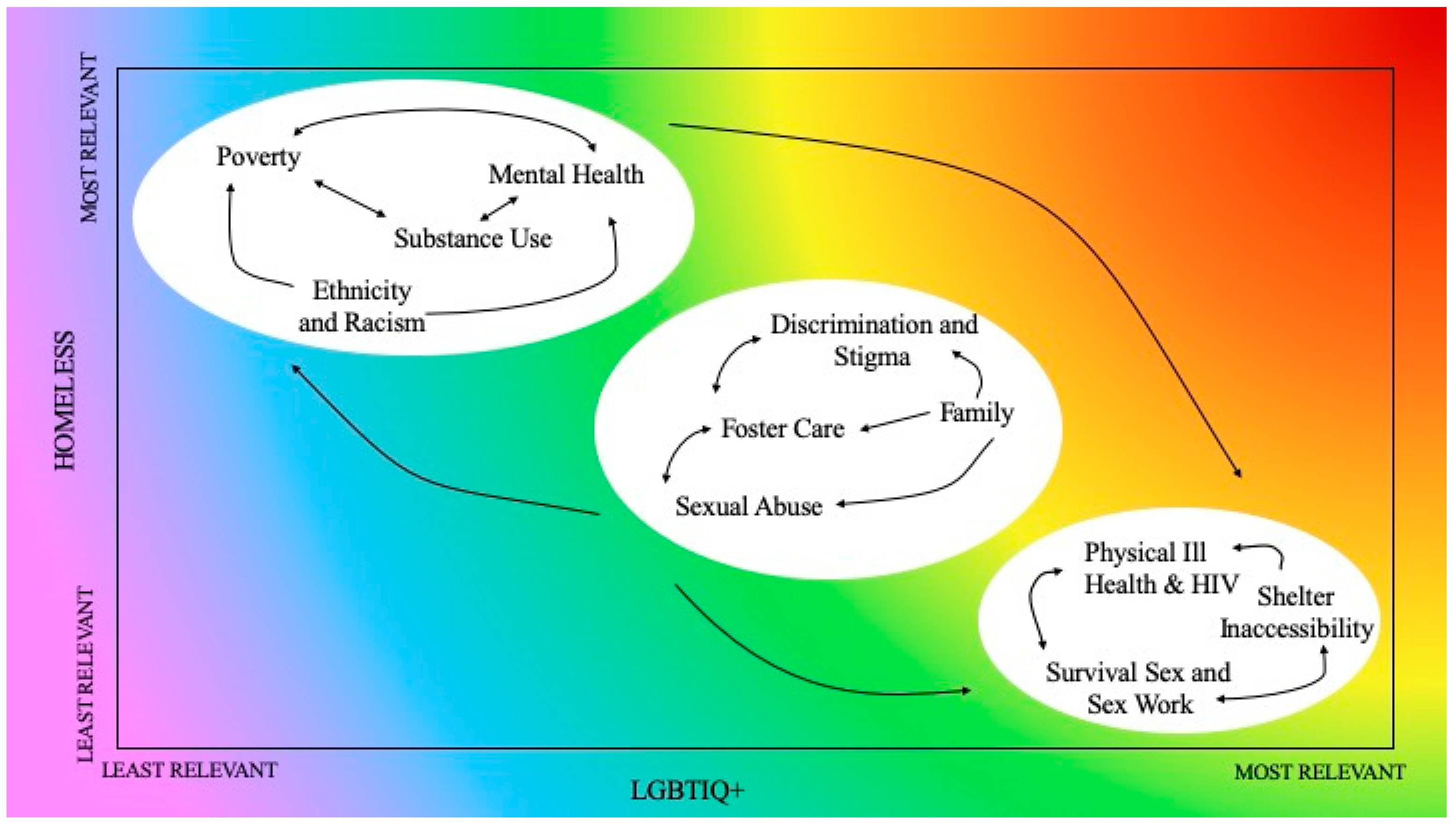

3.1. Key Themes

3.2. Proximate Causes of Homelessness

3.2.1. Poverty

3.2.2. Ethnicity and Racism

3.2.3. Substance Use

3.2.4. Mental Health

3.3. System Failures in Early Life

3.3.1. Sexual Abuse

3.3.2. Foster Care

3.3.3. LGBTIQ+ Discrimination and Stigma

3.3.4. Family

3.4. Experiences During Homelessness

3.4.1. Survival Sex and Sex Work

3.4.2. Physical Ill-Health and Human Immunodeficiency Virus

3.4.3. Shelter Inaccessibility

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Flentje, A.; Leon, A.; Carrico, A.; Zheng, D.; Dilley, J. Mental and Physical Health among Homeless Sexual and Gender Minorities in a Major Urban US City. J. Urban Heal. 2016, 93, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gattis, M.N. An Ecological Systems Comparison Between Homeless Sexual Minority Youths and Homeless Heterosexual Youths. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2013, 39, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milburn, N.G.; Rotheram-Borus, M.J.; Rice, E.; Mallet, S.; Rosenthal, D. Cross-National Variations in Behavioral Profiles Among Homeless Youth. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2006, 372, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournier, M.; Bryn Austin, S.; Samples, C.; Goodenow, C.; Wylie, S.; Corliss, H. A Comparison of Weight-Related Behaviors Among High School Students Who Are Homeless and Non-Homeless. J. Sch. Health 2009, 79, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ecker, J. Queer, Young, and Homeless: A Review of the Literature. Child Youth Serv. 2016, 37, 325–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramovich, A.; Shelton, J. Introduction: Where Are We Now? In Where Am I Going to Go?: Intersectional Approaches to Ending LGBTQ2S Youth Homelessness in Canada & The U.S.; Abramovich, A., Shelton, J., Eds.; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, S.M.; Hartinger-Saunders, R.; Brezina, T.; Beck, E.; Wright, E.R.; Forge, N.; Bride, B.E. Homeless Youth, Strain, and Justice System Involvement. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2016, 62, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, B. European Review of Statistics on Homelessness; European Observatory on Homelessness: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Amore, K.; Viggers, H.; Baker, M.G.; Howden-Chapman, P. Severe Housing Deprivation: The Problem and Its Measurement; Statistics New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2013.

- Crenshaw, K. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex. Univ. Chic. Leg. Forum 1989, 1989, 139. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, L.; Tolhurst, R.; Khanna, R.; Jehan, K. “You’re Disabled, Why Did You Have Sex in the First Place?” An intersectional analysis of experiences of disabled women with regard to their sexual and reproductive health and rights in Gujarat State, India. Glob. Health Action 2017, 10, 1290316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. Forgotten Youth: Homeless LGBT Youth of Color and the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act. Northwest. J. Law Soc. Policy 2017, 12, 17–45. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M.A.; Evans, C.R.; Subramanian, S.V. Can Intersectionality Theory Enrich Population Health Research? Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 178, 214–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualtitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; SAGE Publications, Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nooe, R.; Patterson, D. The Ecology of Homelessness. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2010, 20, 105–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinn, M. Homelessness, Poverty and Social Exclusion in the United States and Europe. Eur. J. Homelessness 2010, 4, 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen, S.; Watts, B. Homelessness and Poverty: Reviewing the Links. In European Network for Housing Research; European Network for Housing Research: Edinburgh, UK, 2014; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton Nicholls, C. Agency, Transgression and the Causation of Homelessness: A Contextualised Rational Action Analysis. Eur. J. Hous. Policy 2009, 9, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilmaghani, M. Sexual Orientation, Labour Earnings, and Household Income in Canada. J. Labor Res. 2018, 39, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozeren, E. Sexual Orientation Discrimination in the Workplace. Procedia -Social Behav. Sci. 2014, 109, 1203–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.M.; Ennett, S.T.; Ringwalt, C.L. Substance Use among Runaway and Homeless Youth in Three National Samples. Am. J. Public Health 1997, 87, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, S.L.; Camlin, C.S.; Ennett, S.T. Substance Use and Risky Sexual Behavior Among Homeless and Runaway Youth. J. Adolesc. Heal. 1998, 23, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirst, M.; Frederick, T.; Erickson, P.G.; Kirst, M.; Frederick, T.; Erickson, P.G. Concurrent Mental Health and Substance Use Problems among Street-Involved Youth. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Addict. 2011, 9, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, T.; Kirst, M.; Erickson, P.G. Substance Use and Mental Health. Adv. Ment. Heal. 2012, 11, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, J.M.; Boyle, S.; Salomonsen-Sautel, S.; Baker, N.D.; Garcia, T.J.; Hoffman, A.; Hopfer, C.J. Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Homeless Youth: An Eight-City Public Health Perspective. Child Welfare 2005, 85, 151–170. [Google Scholar]

- Lankenau, S.E.; Clatts, M.C.; Welle, D.; Goldsamt, L.A.; Gwadz, M.V. Street Careers: Homelessness, Drug Use, and Sex Work among Young Men Who Have Sex with Men (YMSM). Int. J. Drug Policy 2005, 16, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flentje, A.; Shumway, M.; Wong, L.H.; Riley, E.D. Psychiatric Risk in Unstably Housed Sexual Minority Women. Women’s Heal. Issues 2017, 27, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durso, L.; Gates, G. Serving Our Youth; The Williams Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck, L.B.; Chen, X.; Hoyt, D.R.; Tyler, K.A.; Johnson, K.D. Mental Disorder, Subsistence Strategies, and Victimization among Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Homeless and Runaway Adolescents. J. Sex Res. 2004, 41, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, D.C.; Rieb, L.; Nosova, E.; Liu, Y.; Kerr, T.; Debeck, K. Hospitalization among Street-Involved Youth Who Use Illicit Drugs in Vancouver, Canada: A longitudinal analysis. Harm Reduct. J. 2018, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moskowitz, A.; Stein, J.A.; Lightfoot, M. The Mediating Roles of Stress and Maladaptive Behaviors on Self-Harm and Suicide Attempts Among Runaway and Homeless Youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2013, 42, 1015–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, K.J.; Shelton, K.H.; van den Bree, M.B. Mental Health Problems in Young People with Experiences of Homelessness and the Relationship with Health Service Use. Evid. Based Ment. Heal. 2014, 17, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.; Lucassen, M.; Bullen, P.; Denny, S.; Fleming, T.; Robinson, E.; Rossen, F. Young People Attracted to the Same Sex or Both Sexes; The University of Auckland: Auckland, New Zealand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Noell, J.W.; Ochs, L.M. Relationship of Sexual Orientation to Substance Use, Suicidal Ideation, Suicide Attempts, and Other Factors in a Population of Homeless Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2001, 29, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tyler, K.A.; Whitbeck, L.B.; Hoyt, D.R. Early Sexual Abuse, Street Adversity, and Drug Use among Female Homeless and Runaway Adolescents in the Midwest. J. Drug Issues 2004, 34, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, S.A. Youth Homelessness and Social Stigma. J Youth Adolesc. Ment. Heal. Rehabil. 2007, 36, 291–299. [Google Scholar]

- Rew, L.; Taylor-Seehafer, M.; Thomas, N.Y.; Yockey, R.D. Correlates of Resilience in Homeless Adolescents. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2001, 33, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitbeck, L.; Hoyt, D.; Yoder, K.; Cauce, A.; Paradise, M. Deviant Behavior and Victimization Among Homeless and Runaway Adolescents. J. Interpers. Violence 2001, 16, 1175–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, K.A.; Akinyemi, S.L.; Kort-Butler, L.A. Correlates of Service Utilization among Homeless Youth. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 1344–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosario, M.; Schrimshaw, E.W.; Hunter, J. Risk Factors for Homelessness among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youths. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochran, B.N.; Stewart, A.J.; Ginzler, J.A.; Cauce, A.M. Challenges Faced by Homeless Sexual Minorities. Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 773–777. [Google Scholar]

- Rew, L.; Whittaker, T.A.; Taylor-Seehafer, M.A.; Smith, L.R. Sexual Health Risks and Protective Resources in Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Heterosexual Homeless Youth. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2005, 10, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, B.D.; Shannon, K.; Kerr, T.; Zhang, R.; Wood, E. Survival Sex Work and Increased HIV Risk among Sexual Minority Street-Involved Youth. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2010, 53, 661–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cray, A.; Miller, K.; Durso, L.E. Seeking Shelter: The Experiences and Unmet Needs of LGBT Homeless Youth Seeking Shelter The Experiences and Unmet Needs of LGBT Homeless Youth; The Center for American Progress: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Edidin, J.P.; Ganim, Z.; Hunter, S.J.; Karnik, N.S. The Mental and Physical Health of Homeless Youth: A Literature Review. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2012, 43, 354–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healey, C.V.; Fisher, P.A. Young Children in Foster Care and the Development of Favorable Outcomes. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 1822–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, P.J.; Toro, P.A.; Miles, B.W. Pathways to and From Homelessness and Associated Psychosocial Outcomes Among Adolescents Leaving the Foster Care System. Res. Pract. 2008, 99, 1453–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembo, R.; Williams, L.; Schmeidler, J.; Berry, E.; Wothke, W.; Getreu, A.; Wish, E.; Christensen, C. A Structural Model Examining the Relationship Between Physical Child Abuse, Sexual Victimization, and Marijuana/Hashish Use in Delinquent Youth. Violence Vict. 1992, 7, 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, P.A.; Fulkerson, J.M.; Beebe, T.J. Multiple Substance Use Among Adolescent Physical and Sexual Abuse Victims. Child Abuse Negl. 1997, 21, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitbeck, L.B.; Lazoritz, M.; Crawford, D.; Hautala, D. Administration for Children and Families Family and Youth Services Bureau Street Outreach Program Data Collection Study Final Report April 2016; Administration on Children, Youth, and Families: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; No. April. [Google Scholar]

- Walls, N.E.; Hancock, P.; Wisneski, H. Differentiating the Social Service Needs of Homeless Sexual Minority Youth from Those of Non-Homeless Sexual Minority Youths. J. Child. Poverty 2007, 13, 177–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattis, M.N. Psychosocial Problems Associated with Homelessness in Sexual Minority Youths. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2009, 198, 1066–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.D.M.; Kastanis, A.A. Sexual and Gender Minority Disproportionality and Disparities in Child Welfare. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 58, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, P.; Noell, J.; Ochs, L.; Seeley, J.R. Depression, Suicidal Ideation and STD-Related Risk in Homeless Older Adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2001, 24, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidell, M.P. Is There an Emotional Cost of Completing High School? J. Homosex. 2014, 61, 366–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, N. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth: An Epidemic of Homelessness; National Coalition for the Homeless: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ream, G.L.; Barnhart, K.F.; Lotz, K.V. Decision Processes about Condom Use among Shelter-Homeless LGBT Youth in Manhattan. AIDS Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 659853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, B.A. Child Welfare Systems and LGBTQ Youth Homelessness. Child Welfare 2018, 69, 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mountz, S.; Capous-Desyllas, M.; Pourciau, E. “Because We’re Fighting to Be Ourselves:” Voices from Former Foster Youth Who Are Transgender and Gender Expansive. Child Welfare 2018, 96, 103–125. [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein, R.; Greenblatt, A.; Hass, L.; Kohn, S.; Rana, J. Justice for All? A Report on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgendered Youth in the New York Juvenile Justice System; Urban Justice Center: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 1–71. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, J.; Rosenwald, M. Foster Parents’ Perspectives on LGB Youth in the Child Welfare System. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2007, 19, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, D. The Role of Institutional Placement, Family Conflict, and Homosexuality in Homelessness Pathways Among Latino LGBT Youth in New York City. J. Homosex. 2016, 63, 601–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corliss, H.L.; Goodenow, C.S.; Nichols, L.; Bryn Austin, S. High Burden of Homelessness among Sexual-Minority Adolescents. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 1683–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunåker, C. “No Place like Home?” Locating Homeless LGBT Youth. Home Cult. 2015, 12, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramovich, A. Preventing, Reducing and Ending LGBTQ2S Youth Homelessness: The Need for Targeted Strategies. Soc. Incl. 2016, 4, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, J.; Bond, L. “It Just Never Worked Out”: How Transgender and Gender Expansive Youth Understand Their Pathways into Homelessness. Fam. Soc. J. Contemp. Soc. Serv. 2017, 98, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forge, N.; Hartinger-Saunders, R.; Wright, E.; Ruel, E. Out of the System and onto the Streets. Child Welfare 2018, 96, 47–74. [Google Scholar]

- Shelton, J. Reframing Risk for Transgender and Gender-Expansive Young People Experiencing Homelessness. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2016, 28, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, N.E.; Bell, S. Correlates of Engaging in Survival Sex among Homeless Youth and Young Adults. J. Sex Res. 2011, 48, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, K.A.; Schmitz, R.M. A Comparison of Risk Factors for Various Forms of Trauma in the Lives of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Heterosexual Homeless Youth. J. Trauma Dissociation 2018, 19, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangamma, R.; Slesnick, N.; Toviessi, P.; Serovich, J. Comparison of HIV Risks among Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Heterosexual Homeless Youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2008, 37, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, M.W.; McFarland, W.; Kellogg, T.; Baxter, M.; Katz, M.H.; MacKellar, D.; Valleroy, L.A. HIV Risk Behaviour of Runaway Youth in San Francisco. Youth Soc. 2000, 32, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman-Adhikari, A.; Rice, E.; Bender, K.; Lengnick-Hall, R.; Yoshioka-Maxwell, A.; Rhoades, H. Social Networking Technology Use and Engagement in HIV-Related Risk and Protective Behaviors Among Homeless Youth. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rosa, C.J.; Montgomery, S.B.; Hyde, J.; Iverson, E.; Kipke, M.D. HIV Risk Behavior and HIV Testing. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2001, 13, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maccio, E.M.; Ferguson, K.M. Services to LGBTQ Runaway and Homeless Youth. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2016, 63, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramovich, A. Understanding How Policy and Culture Create Oppressive Conditions for LGBTQ2S Youth in the Shelter System. J. Homosex. 2016, 64, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begun, S.; Kattari, S.K. Conforming for Survival: Associations between Transgender Visual Conformity/Passing and Homelessness Experiences. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2016, 28, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, I.; Chin, M.; Chapra, A.; Ricciardi, J. A ‘Normative’ Homeless Woman?: Marginalisation, Emotional Injury, and Social Support of Transwomen Experiencing Homelessness. Gay Lesbian Issues Psychol. Rev. 2009, 5, 2–19. [Google Scholar]

- Spicer, S.S. Healthcare Needs of the Transgender Homeless Population. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2010, 14, 320–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleace, N. Housing First Guide Europe. 2016, p. 90. Available online: http://housingfirstguide.eu/website/ (accessed on 1 August 2017).

- Fitzpatrick, S.; Bramley, G.; Johnsen, S. Pathways into Multiple Exclusion Homelessness in Seven UK Cities. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 148–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, R.; Marksamer, J. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Young People in State Custody. Temple Law Rev. 2006, 79, 415–438. [Google Scholar]

- Mallon, G.P. We Don’t Exactly Get the Welcome Wagon: The Experiences of Gay and Lesbian Adolescents in Child Welfare Systems; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, J.M.; Ennett, S.T.; Ringwalt, C.L. Prevalence and Correlates of Survival Sex among Runaway and Homeless Youth. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1406–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, E. What’s Good for the Gays Is Good for the Gander: Making Homeless Youth Housing Safer for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth. Fam. Court Rev. 2008, 46, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, J. Transgender Youth Homelessness: Understanding Programmatic Barriers through the Lens of Cisgenderism. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 59, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, K.M.; Maccio, E.M. Promising Programs for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer/Questioning Runaway and Homeless Youth. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2015, 41, 659–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensign, J.; Bell, M. Illness Experiences of Homeless Youth. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 1239–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fraser, B.; Pierse, N.; Chisholm, E.; Cook, H. LGBTIQ+ Homelessness: A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2677. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16152677

Fraser B, Pierse N, Chisholm E, Cook H. LGBTIQ+ Homelessness: A Review of the Literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(15):2677. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16152677

Chicago/Turabian StyleFraser, Brodie, Nevil Pierse, Elinor Chisholm, and Hera Cook. 2019. "LGBTIQ+ Homelessness: A Review of the Literature" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 15: 2677. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16152677

APA StyleFraser, B., Pierse, N., Chisholm, E., & Cook, H. (2019). LGBTIQ+ Homelessness: A Review of the Literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(15), 2677. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16152677