Exploring the Healthcare Seeking Behavior of Medical Aid Beneficiaries Who Overutilize Healthcare Services: A Qualitative Descriptive Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Setting

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Rigor

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

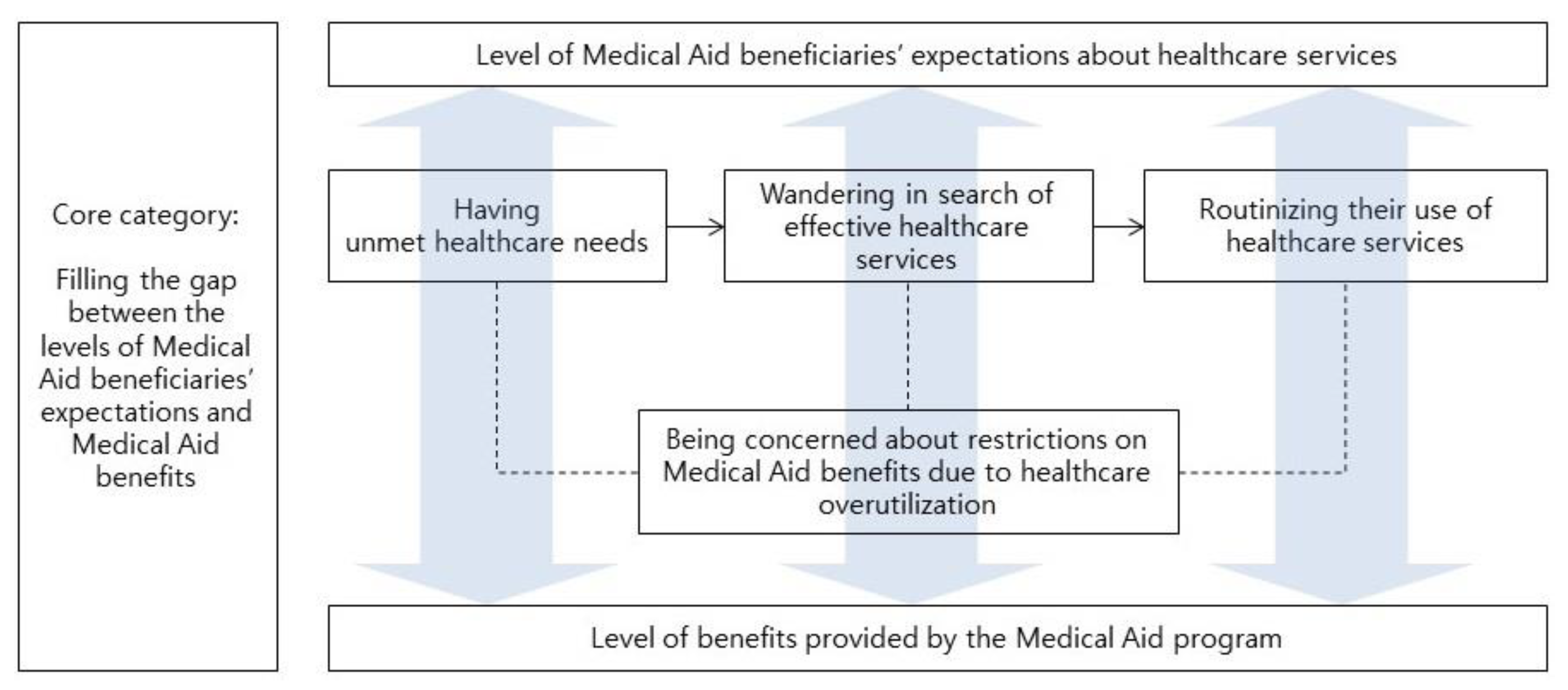

3.2. MA Beneficiaries’ Healthcare Seeking Process

3.2.1. Having Unmet Healthcare Needs

“I heard that there’s a difference between the medication that you pay for and the medication that is covered by the MA benefits, even if it’s the same. I have heard that medications given to MA beneficiaries are the least potent. I think that’s why I don’t get any better after taking these medications. It is unfair! Higher potent medications are not given to us, MA beneficiaries, because they are expensive. I, as a beneficiary, think this is absolutely unfair!” (P1)

3.2.2. Wandering in Search of Effective Healthcare Services

“Initially, I was skeptical as to whether they would really give me medical benefits. Once I saw a huge reduction in my medication costs, I felt the advantage of having the MA benefits. I was thinking, ‘Is this true? Would it change in the future?” (P4)

“I experienced no improvement in symptoms regardless of which hospital I visited. Treatments were of no use, and that’s why I keep switching from one hospital to another. A doctor once told me my disease would not be cured. I feel frustrated, so I keep changing hospitals because of this frustration.” (P7)

3.2.3. Routinizing Their Use of Healthcare Services

“I wake up in the morning, eat breakfast, go to a hospital around 11 am or noon, receive physiotherapy, and then go to an otolaryngology clinic because my throat hurts. Sometimes, the sun is already setting after I’ve visited hospitals.” (P10)

“I go to the hospital every day, so it feels like going home now. I go there without much thought, and then I return home. I can’t go when the hospital is closed, but when it is open, I go there to receive physiotherapy, get shots, and so forth. There’s a clinic 200 m away. I walk up to the hospital and consider it exercise.” (P5)

3.2.4. Being Concerned about Restrictions on MA Benefits Due to Healthcare Overutilization

“I just have to bear the pain. I feel embarrassed and sorry every time I receive a letter from the hospital. But I am trying as much as possible not to go to hospitals. I don’t want to add more burdens to my country. I keep having this thought.” (P2)

“I am super worried about hospital designation. I don’t think I’ll be able to stand it if I get a designated hospital. That’s why every time I come back from a hospital, I record the date of the visit, prescriptions, and everything.” (P2)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Guideline for Medical Aid Program in 2018; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Sejong, Korea, 2018.

- Shin, Y.S. On the appropriate use of health services. Health Welf. Pol. Forum. 2006, 114, 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- The Commonwealth Fund. International Profiles of Health Care Systems. 2017. Available online: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_fund_report_2017_may_mossialos_intl_profiles_v5.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2018).

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, K.S.; Yoo, K.B.; Park, E.C. The differences in health care utilization between Medical Aid and Health Insurance: A longitudinal study using propensity score matching. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shon, C.W.; Kim, J.A. Reality of Healthcare Utilization and Health Behaviors of Medical Aid Beneficiaries in Seoul; The Seoul Institute: Seoul, Korea, 2017; Available online: www.si.re.kr (accessed on 22 February 2018).

- National Health Insurance Service. 2017 National Health Insurance Statistical Yearbook. 2018. Available online: http://www.nhis.or.kr/menu/boardRetriveMenuSet.xx?menuId=F3322/ (accessed on 22 February 2018).

- Song, M.K. Experiences of Health Care Utilization among Medical Aid Excessive Users in Korea. Master’s Thesis, Hanyang University, Seoul, Korea, 2015. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Shon, C. The effects of health coverage schemes on length of stay and preventable hospitalization in Seoul. Int. J. Environ. Res Public Health 2018, 15, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.H.; Lee, Y.J. Qualitative analysis of medical usage patterns of medical aid patients. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2017, 17, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. Whatever happended to qualitative description? Res. Nurs. Health 2000, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elo, S.; Kyngas, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Long, T.; Johnson, M. Rigour, reliability and validity in qualitative research. Clin. Effect. Nurs. 2000, 4, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J. Healthcare utilization and out-of-pocket spending of Medical Aids recipients in South Korea: A propensity score matching with National Health Insurance participants. Korean J. Health Econ. Pol. 2016, 22, 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, M.P.; Barker, M. Why is changing health-related behaviour so difficult? Public Health 2016, 136, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pender, N.J. Health Promotion in Nursing Practice, 3rd ed.; Appleton and Lange: Stamford, CT, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H.W.; Yeo, N.K. Current state and challenges of Medical Aid program. Health Welf. Pol. Forum. 2016, 241, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.J.; Lim, J.Y. The effects of introduction of co-payment system on the Medical Aid beneficiaries’ health care usage in Korea. Korean J. Health Econ. Pol. 2013, 19, 23–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, L.; Bodenheimer, T. Expanded roles of registered nurses in primary care delivery of the future. Nurs. Outlook 2017, 65, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, C.M.; Reider, L.; Frey, K.; Scharfstein, D.; Leff, B.; Wolff, J.; Groves, C.; Karm, L.; Wegener, S.; Marsteller, J.; et al. The effects of guided care on the perceived quality of health care for multi-morbid older persons: 18-month outcomes from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010, 25, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesney, M.L.; Duderstadt, K.G. Affordable Care Act: Medicaid expansion key to increasing access to care. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2013, 27, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glendenning-Napoli, A.; Dowling, B.; Pulvino, J.; Baillargeon, G.; Raimer, B.G. Community-based case management for uninsured patients with chronic diseases: Effects on acute care utilization and costs. Prof. Case Manag. 2012, 17, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.Y.; Liu, M.F. Case management effectiveness in reducing hospital use: A systematic review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2017, 64, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliam, C.L.; Stewart, M.; Desai, K.; Wade, T.; Galajda, J. Case management approaches for in-home care. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2000, 13, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, J.; Rice, E. Case management. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 50, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.Y.; Huber, D.L. An integrative review of nurse-led community-based case management effectiveness. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2014, 61, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massimi, A.; De Vito, C.; Brufola, I.; Corsaro, A.; Marzuillo, C.; Migliara, G.; Rega, M.L.; Ricciardi, W.; Villari, P.; Damiani, G. Are community-based nurse-led self-management support interventions effective in chronic patients? Results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cho, J.; Jeong, K.; Kim, S.; Kim, H. Exploring the Healthcare Seeking Behavior of Medical Aid Beneficiaries Who Overutilize Healthcare Services: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2485. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142485

Cho J, Jeong K, Kim S, Kim H. Exploring the Healthcare Seeking Behavior of Medical Aid Beneficiaries Who Overutilize Healthcare Services: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(14):2485. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142485

Chicago/Turabian StyleCho, Jeonghyun, Kyungin Jeong, Samsook Kim, and Hyejin Kim. 2019. "Exploring the Healthcare Seeking Behavior of Medical Aid Beneficiaries Who Overutilize Healthcare Services: A Qualitative Descriptive Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 14: 2485. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142485

APA StyleCho, J., Jeong, K., Kim, S., & Kim, H. (2019). Exploring the Healthcare Seeking Behavior of Medical Aid Beneficiaries Who Overutilize Healthcare Services: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(14), 2485. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142485