Problem Drinking, Alcohol-Related Violence, and Homelessness among Youth Living in the Slums of Kampala, Uganda

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

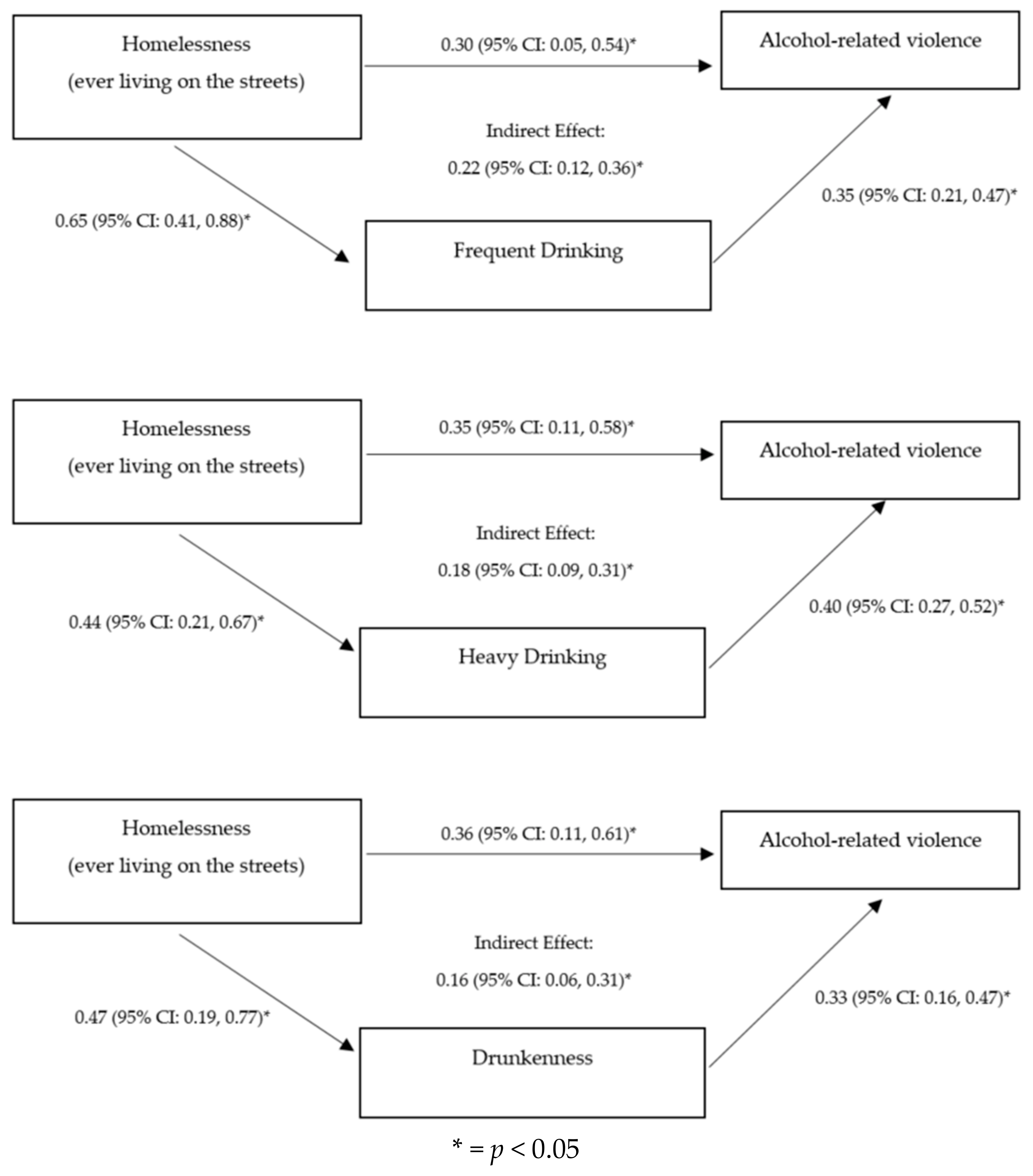

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (Violence and Injury Prevention) Youth Violence. 2018. Available online: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/youth/en (accessed on 21 February 2018).

- Choi, H.J.; Elmquist, J.; Shorey, R.C.; Rothman, E.F.; Stuart, G.L.; Temple, J.R. Stability of alcohol use and teen dating violence for female youth: A latent transition analysis. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2017, 36, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohl, B.C.; Wiley, S.; Wiebe, D.J.; Culyba, A.J.; Drake, R.; Branas, C.C. Association of Drug and Alcohol Use with Adolescent Firearm Homicide at Individual, Family, and Neighborhood Levels. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, R.P.; Almeida, M.C.; Fabry, B.; Reitz, A.L. A scale to measure restrictiveness of living environments for troubled children and youths. Hosp. Community Psychiatry 1992, 43, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Global Status on Violence Prevention 2014; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Rossow, I. Alcohol-related violence: The impact of drinking pattern and drinking context. Addict. Abingdon Engl. 1996, 91, 1651–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norström, T.; Ramstedt, M. Mortality and population drinking: A review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2005, 24, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naimi, T.S.; Xuan, Z.; Coleman, S.M.; Lira, M.C.; Hadland, S.E.; Cooper, S.E.; Heeren, T.C.; Swahn, M.H. Alcohol Policies and Alcohol-Involved Homicide Victimization in the United States. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2017, 78, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hockin, S.; Rogers, M.L.; Pridemore, W.A. Population-level alcohol consumption and national homicide rates. Eur. J. Criminol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinty, E.E.; Webster, D.W. The Roles of Alcohol and Drugs in Firearm Violence. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 324–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obot, I.S. Alcohol use and related problems in sub-Saharan Africa. Afr. J. Drug Alcohol Stud. 2006, 5, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kabiru, C.W.; Beguy, D.; Crichton, J.; Ezeh, A.C. Self-reported drunkenness among adolescents in four sub-Saharan African countries: Associations with adverse childhood experiences. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2010, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkowane, M.A.; Rocha-Silva, L.; Saxena, S.; Mbatia, J.; Ndubani, P.; Weir-Smitii, G. Psychoactive substance use among young people: Findings of a multi-center study in three African countries. Contemp. Drug Probl. 2004, 31, 329–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, K.A.; Handema, R.; Schmitz, R.M.; Phiri, F.; Kuyper, K.S.; Wood, C. Multi-Level Risk and Protective Factors for Substance Use Among Zambian Street Youth. Subst. Use Misuse 2016, 51, 922–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bye, E.K.; Rossow, I. The impact of drinking pattern on alcohol-related violence among adolescents: An international comparative analysis. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010, 29, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svensson, J.; Landberg, J. Is Youth Violence Temporally Related to Alcohol? A Time-Series Analysis of Binge Drinking, Youth Violence and Total Alcohol Consumption in Sweden. Alcohol Alcohol. 2013, 48, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swahn, M.H.; Donovan, J.E. Alcohol and violence: Comparison of the psychosocial correlates of adolescent involvement in alcohol-related physical fighting versus other physical fighting. Addict. Behav. 2006, 31, 2014–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loeber, R.; Ahonen, L.; Stallings, R.; Farrington, D.P. Violence De-Mystified: Findings on Violence by Young Males in the Pittsburgh Youth Study. Can. Psychol. 2017, 58, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swahn, M.H.; Simon, T.R.; Hammig, B.J.; Guerrero, J.L. Alcohol-consumption behaviors and risk for physical fighting and injuries among adolescent drinkers. Addict. Behav. 2004, 29, 959–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swahn, M.H.; Donovan, J.E. Correlates and predictors of violent behavior among adolescent drinkers. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2004, 34, 480–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swahn, M.H.; Donovan, J.E. Predictors of fighting attributed to alcohol use among adolescent drinkers. Addict. Behav. 2005, 30, 1317–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Recent Developments in Alcoholism; Galanter, M. (Ed.) Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Volume 13, ISBN 0-306-45358-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, K.A.; Melander, L.A. Child abuse, street victimization, and substance use among homeless young adults. Youth Soc. 2015, 47, 502–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, P.R.; Josephs, R.A.; Parrott, D.J.; Duke, A.A. Alcohol Myopia Revisited: Clarifying Aggression and Other Acts of Disinhibition Through a Distorted Lens. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. J. Assoc. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 5, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.P. Aggressive behavior and physiological arousal as a function of provocation and the tendency to inhibit aggression. J. Pers. 1967, 35, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topalli, V.; Giancola, P.R.; Tarter, R.E.; Swahn, M.; Martel, M.M.; Godlaski, A.J.; Mccoun, K.T. The Persistence of Neighborhood Disadvantage: An Experimental Investigation of Alcohol and Later Physical Aggression. Crim. Just. Behav. 2014, 41, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeber, R.; Farrington, D.P.; Stouthamer-Loeber, M.; Van Kammen, W.B. Antisocial Behavior and Mental Health Problems: Explanatory Factors in Childhood and Adolescence; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; ISBN 0-8058-2956-3. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, R.J. Racial Stratification and the Durable Tangle of Neighborhood Inequality. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2009, 621, 260–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisenberg, E.; Herrenkohl, T. Community violence in context: Risk and resilience in children and families. J. Interpers. Violence 2008, 23, 296–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olumide, A.O.; Robinson, A.C.; Levy, P.A.; Mashimbye, L.; Brahmbhatt, H.; Lian, Q.; Ojengbede, O.; Sonenstein, F.L.; Blum, R.W. Predictors of substance use among vulnerable adolescents in five cities: Findings from the well-being of adolescents in vulnerable environments study. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2014, 55, S39–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roche, A.; Kostadinov, V.; Fischer, J.; Nicholas, R.; O’Rourke, K.; Pidd, K.; Trifonoff, A. Addressing inequities in alcohol consumption and related harms. Health Promot. Int. 2015, 30 (Suppl. 2), ii20–ii35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swahn, M.H.; Culbreth, R.E.; Staton, C.A.; Self-Brown, S.R.; Kasirye, R. Alcohol-Related Physical Abuse of Children in the Slums of Kampala, Uganda. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swahn, M.H.; Gressard, L.; Palmier, J.B.; Kasirye, R.; Lynch, C.; Yao, H. Serious Violence Victimization and Perpetration among Youth Living in the Slums of Kampala, Uganda. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2012, 13, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swahn, M.H.; Dill, L.J.; Palmier, J.B.; Kasirye, R. Girls and Young Women Living in the Slums of Kampala. SAGE Open 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swahn, M.H.; Culbreth, R.; Salazar, L.F.; Kasirye, R.; Seeley, J. Prevalence of HIV and Associated Risks of Sex Work among Youth in the Slums of Kampala. AIDS Res. Treat. 2016, 2016, 5360180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swahn, M.H.; Palmier, J.B.; Kasirye, R.; Yao, H. Correlates of Suicide Ideation and Attempt among Youth Living in the Slums of Kampala. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 596–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, M.H.; Dworsky, A.; Matjasko, J.L.; Curry, S.R.; Schlueter, D.; Chávez, R.; Farrell, A.F. Prevalence and Correlates of Youth Homelessness in the United States. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2018, 62, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppong Asante, K.; Meyer-Weitz, A. International note: Association between perceived resilience and health risk behaviours in homeless youth. J. Adolesc. 2015, 39, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, J.M.; Ennett, S.T.; Ringwalt, C.L. Substance use among runaway and homeless youth in three national samples. Am. J. Public Health 1997, 87, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN Habitat Cities in a Globalizing World. London. 2001. Available online: http://www.un.org/en/events/pastevents/pdfs/Cities_in_a_globalizing_world_2001.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Lee, B.A.; Schreck, C.J. Danger on the Streets: Marginality and Victimization among Homeless People. Am. Behav. Sci. 2005, 48, 1055–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaetz, S. Safe Streets for Whom? Homeless Youth, Social Exclusion, and Criminal Victimization. Can. J. Criminol. Crim. Just. 2004, 46, 423–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitbeck, L.B.; Simons, R.L. A comparison of adaptive strategies and patterns of victimization among homeless adolescents and adults. Violence Vict. 1993, 8, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morewitz, S.J. Delinquent/Criminal and Violent Behavior. In Runaway and Homeless Youth; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Renzaho, A.M.N.; Kamara, J.K.; Stout, B.; Kamanga, G. Child rights and protection in slum settlements of Kampala, Uganda: A qualitative study. J. Hum. Rights 2017, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerde, J.A.; Hemphill, S.A.; Scholes-Balog, K.E. ‘Fighting’ for survival: A systematic review of physically violent behavior perpetrated and experienced by homeless young people. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2014, 19, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, E.R.; Attell, B.K.; Ruel, E. Social Support Networks and the Mental Health of Runaway and Homeless Youth. Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csiernik, R.; Forchuk, C.; Buccieri, K.; Richardson, J.; Rudnick, A.; Warner, L.; Wright, A. Substance Use of Homeless and Precariously Housed Youth in a Canadian Context. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2016, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edidin, J.P.; Ganim, Z.; Hunter, S.J.; Karnik, N.S. The Mental and Physical Health of Homeless Youth: A Literature Review. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2012, 43, 354–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, B.R.; Allen, N.B. Review: Trauma and homelessness in youth: Psychopathology and intervention. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 54, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uganda Youth Development Link | Official Website. Available online: http://www.uydel.org/ (accessed on 31 August 2015).

- World Health Organization Global School-Based Student Health Survey. Available online: http://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/gshs/en/ (accessed on 8 August 2017).

- Conigrave, K.M.; Hall, W.D.; Saunders, J.B. The AUDIT questionnaire: Choosing a cut-off score. Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test. Addict. Abingdon Engl. 1995, 90, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, J.A. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA 1984, 252, 1905–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USAid Uganda AIDS Indicator Survey. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/AIS10/AIS10.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2017).

- USAID Demographic Health Survey. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/ (accessed on 8 August 2017).

- Francis, J.M.; Grosskurth, H.; Changalucha, J.; Kapiga, S.H.; Weiss, H.A. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Prevalence of alcohol use among young people in eastern Africa. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2014, 19, 476–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairbairn, N.; Wood, E.; Dobrer, S.; Dong, H.; Kerr, T.; Debeck, K. The relationship between hazardous alcohol use and violence among street-involved youth. Am. J. Addict. 2017, 26, 852–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heerde, J.; Hemphill, S. Is Substance Use Associated with Perpetration and Victimization of Physically Violent Behavior and Property Offences Among Homeless Youth? A Systematic Review of International Studies. Child Youth Care Forum 2015, 44, 277–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehm, J.; Greenfield, T.K.; Rogers, J.D. Average volume of alcohol consumption, patterns of drinking, and all-cause mortality: Results from the US National Alcohol Survey. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 153, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Wert, M.; Mishna, F.; Trocmé, N.; Fallon, B. Which maltreated children are at greatest risk of aggressive and criminal behavior? An examination of maltreatment dimensions and cumulative risk. Child Abuse Negl. 2017, 69, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cronley, C.; Jeong, S.; Davis, J.B.; Madden, E. Effects of Homelessness and Child Maltreatment on the Likelihood of Engaging in Property and Violent Crime During Adulthood. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2015, 25, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.J.; Bender, K.; Windsor, L.; Cook, M.S.; Williams, T. Homeless youth: Characteristics, contributing factors, and service options. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2010, 20, 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brauw, A.; Mueller, V.; Lee, H.L. The Role of Rural-Urban Migration in the Structural Transformation of Sub-Saharan Africa. World Dev. 2014, 63, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embleton, L.; Atwoli, L.; Ayuku, D.; Braitstein, P. The journey of addiction: Barriers to and facilitators of drug use cessation among street children and youths in Western Kenya. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, X. A Review of Interventions for Substance Use among Homeless Youth. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2013, 23, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Alcohol-related Violence n = 158 (45.7%) | No alcohol-related Violence n = 188 (54.3%) | Total Sample | Chi-Square, (df), p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 79 (50.0%) | 76 (40.3%) | 155 (44.8%) | 3.18, (1), p = 0.07 |

| Female | 79 (50.0%) | 112 (59.6%) | 191 (55.2%) | |

| Age, median (IQR) * | 17.0 (1.0) | 17.0 (2.0) | 17.0 (2.0) | p = 0.38 |

| Education | 2.60, (2), p = 0.27 | |||

| <Primary | 63 (40.1%) | 60 (32.3%) | 123 (35.9%) | |

| Completed primary | 34 (21.7%) | 41 (22.0%) | 75 (21.9%) | |

| >Secondary | 60 (38.2%) | 85 (45.7%) | 145 (42.3%) | |

| Parental alcohol use | 4.55, (1), p = 0.03 | |||

| Yes | 117 (74.5%) | 120 (63.8%) | 237 (68.7%) | |

| No | 40 (25.5%) | 68 (36.2%) | 108 (31.3%) | |

| Childhood abuse | 6.85, (1), p = 0.009 | |||

| Yes | 87 (55.1%) | 77 (41.0%) | 164 (47.4%) | |

| No | 71 (44.9%) | 111 (59.0%) | 182 (52.6%) | |

| Ever living on the streets (homelessness) | 13.87, (1), p = 0.0002 | |||

| Yes | 78 (49.4%) | 56 (29.8%) | 134 (38.7%) | |

| No | 80 (50.6%) | 132 (70.2%) | 212 (61.3%) | |

| Problem drinking (CAGE) | 16.87, (1), p < 0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 94 (59.9%) | 70 (37.6%) | 164 (47.8%) | |

| No | 63 (40.1%) | 116 (62.4%) | 179 (52.2%) | |

| Alcohol use frequency | 23.08, (1), p < 0.0001 | |||

| <4 times a month >5 a month | 57 (36.1%) 101 (63.9%) | 116 (62.0%) 71 (38.0%) | 173 (50.1%) 172 (49.9%) | |

| Number of drinks per day | 27.7, (1), p < 0.0001 | |||

| 1–2 drinks | 65 (41.1%) | 129 (69.4%) | 194 (56.4%) | |

| 3 or more drinks | 93 (58.9%) | 57 (30.7%) | 150 (43.6%) | |

| Binge drinking days past | 23.73, (1), p < 0.0001 | |||

| month | ||||

| 0 days | 26 (16.6%) | 76 (40.6%) | 102 (29.7%) | |

| 1 or more days | 131 (83.4%) | 111 (59.4%) | 242 (70.4%) | |

| Number of days drunk | 13.97, (1), p = 0.0002 | |||

| 0 days | 17 (10.8%) | 50 (26.7%) | 67 (19.4%) | |

| 1 or more days | 141 (89.2%) | 137 (73.3%) | 278 (80.6%) |

| Because of Your Own Alcohol Use, How Often during the Last 12 Months Have You Experienced the Following: | Non-problem Drinkers by CAGE Scores, n = 180 (52.3%) | Problem Drinkers by CAGE Scores, n = 164 (47.7%) | Total (n = 344) | Chi-Square, df, p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Got in a fight | ||||

| Never | 116 (64.8%) | 70 (42.7%) | 186 (54.2%) | 16.87, (1), p < 0.0001 |

| 1 or more times | 63 (35.2%) | 94 (57.3%) | 157 (45.8%) | |

| Got in an accident | ||||

| Never | 147 (82.2%) | 115 (70.1%) | 262 (76.4%) | 6.83, (1), p = 0.009 |

| 1 or more times | 32 (17.9%) | 49 (29.9%) | 81 (23.6%) | |

| Had serious problems with your parents | ||||

| Never | 140 (78.2%) | 90 (54.9%) | 230 (67.1%) | 21.09, (1), p < 0.0001 |

| 1 or more times | 39 (21.8%) | 74 (45.1%) | 113 (32.9%) | |

| Had serious problems with your friends | ||||

| Never | 110 (61.5%) | 63 (38.4%) | 173 (50.4%) | 18.17, (1), p < 0.0001 |

| 1 or more times | 69 (38.6%) | 101 (61.6%) | 170 (49.6%) | |

| Was a victim of robbery or theft | ||||

| Never | 146 (81.6%) | 111 (67.7%) | 257 (74.9%) | 8.78, (1), p = 0.003 |

| 1 or more times | 33 (18.4%) | 53 (32.3%) | 86 (25.1%) | |

| Had trouble with the police | ||||

| Never | 152 (84.9%) | 126 (76.8%) | 278 (81.0%) | 3.64, (1), p = 0.06 |

| 1 or more times | 27 (15.1%) | 38 (23.2%) | 65 (19.0%) | |

| Had to go to a hospital | ||||

| Never | 162 (90.5%) | 122 (74.4%) | 284 (82.8%) | 15.60, (1), p < 0.0001 |

| 1 or more times | 17 (9.5%) | 42 (25.6%) | 59 (17.2%) |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Swahn, M.H.; Culbreth, R.; Tumwesigye, N.M.; Topalli, V.; Wright, E.; Kasirye, R. Problem Drinking, Alcohol-Related Violence, and Homelessness among Youth Living in the Slums of Kampala, Uganda. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15061061

Swahn MH, Culbreth R, Tumwesigye NM, Topalli V, Wright E, Kasirye R. Problem Drinking, Alcohol-Related Violence, and Homelessness among Youth Living in the Slums of Kampala, Uganda. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(6):1061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15061061

Chicago/Turabian StyleSwahn, Monica H., Rachel Culbreth, Nazarius Mbona Tumwesigye, Volkan Topalli, Eric Wright, and Rogers Kasirye. 2018. "Problem Drinking, Alcohol-Related Violence, and Homelessness among Youth Living in the Slums of Kampala, Uganda" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 6: 1061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15061061

APA StyleSwahn, M. H., Culbreth, R., Tumwesigye, N. M., Topalli, V., Wright, E., & Kasirye, R. (2018). Problem Drinking, Alcohol-Related Violence, and Homelessness among Youth Living in the Slums of Kampala, Uganda. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(6), 1061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15061061