The Acute Effects of Intermittent Light Exposure in the Evening on Alertness and Subsequent Sleep Architecture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

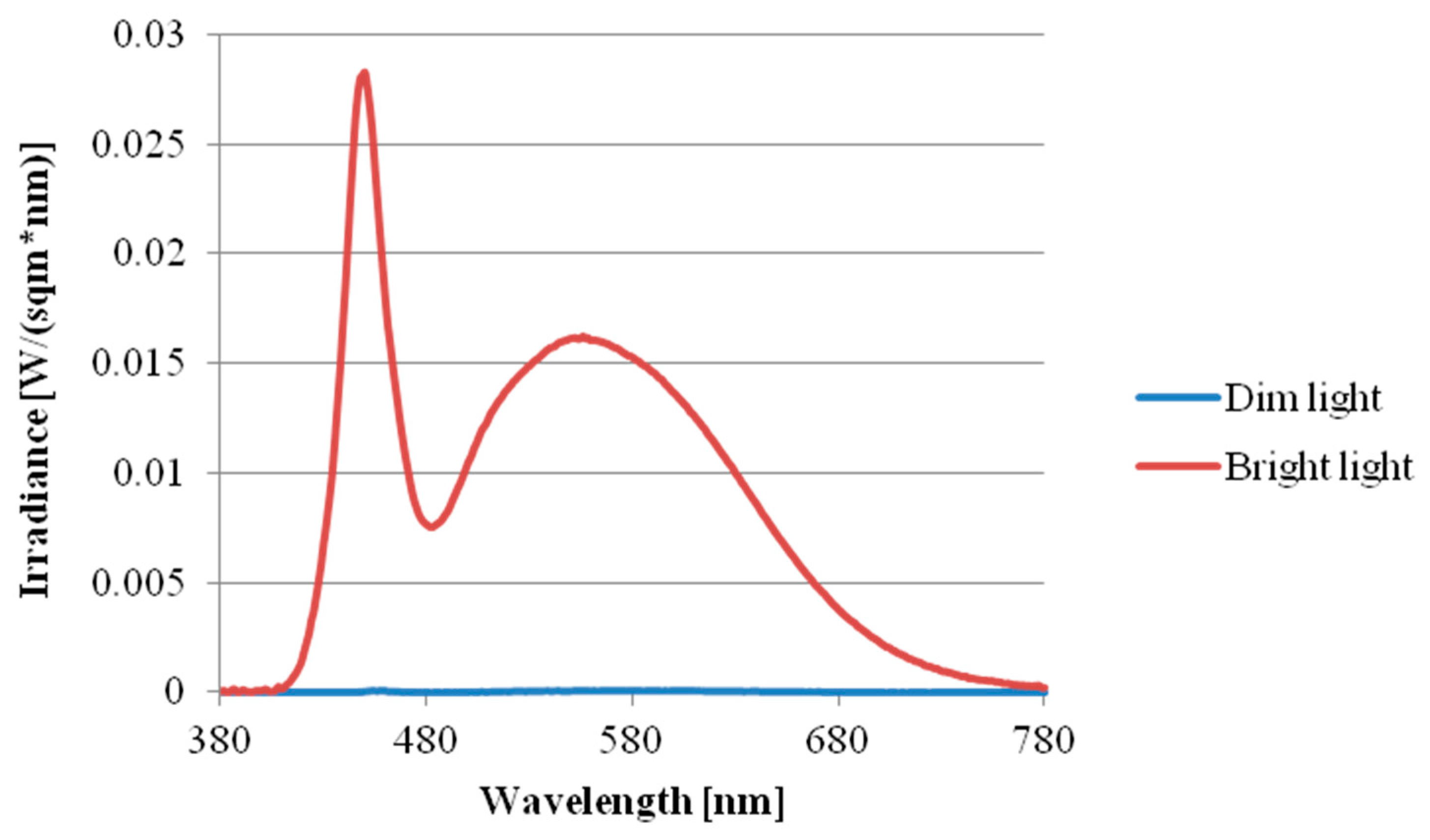

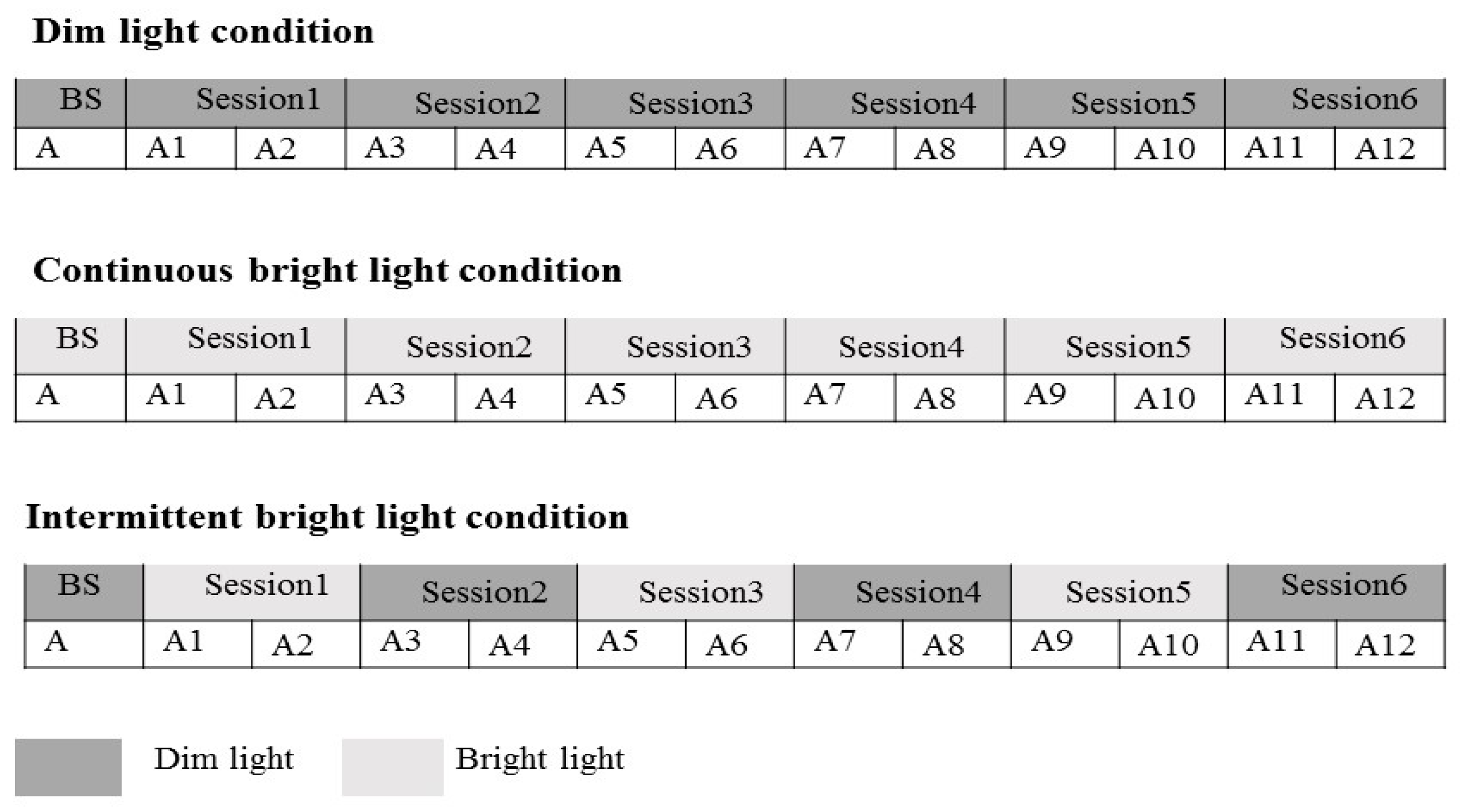

2.2. Research Design and Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Psychomotor Vigilance Task (PVT)

2.3.2. Karolinska Sleepiness Scale (KSS)

2.3.3. Sleep Recording

2.4. Statistics Analysis

3. Results

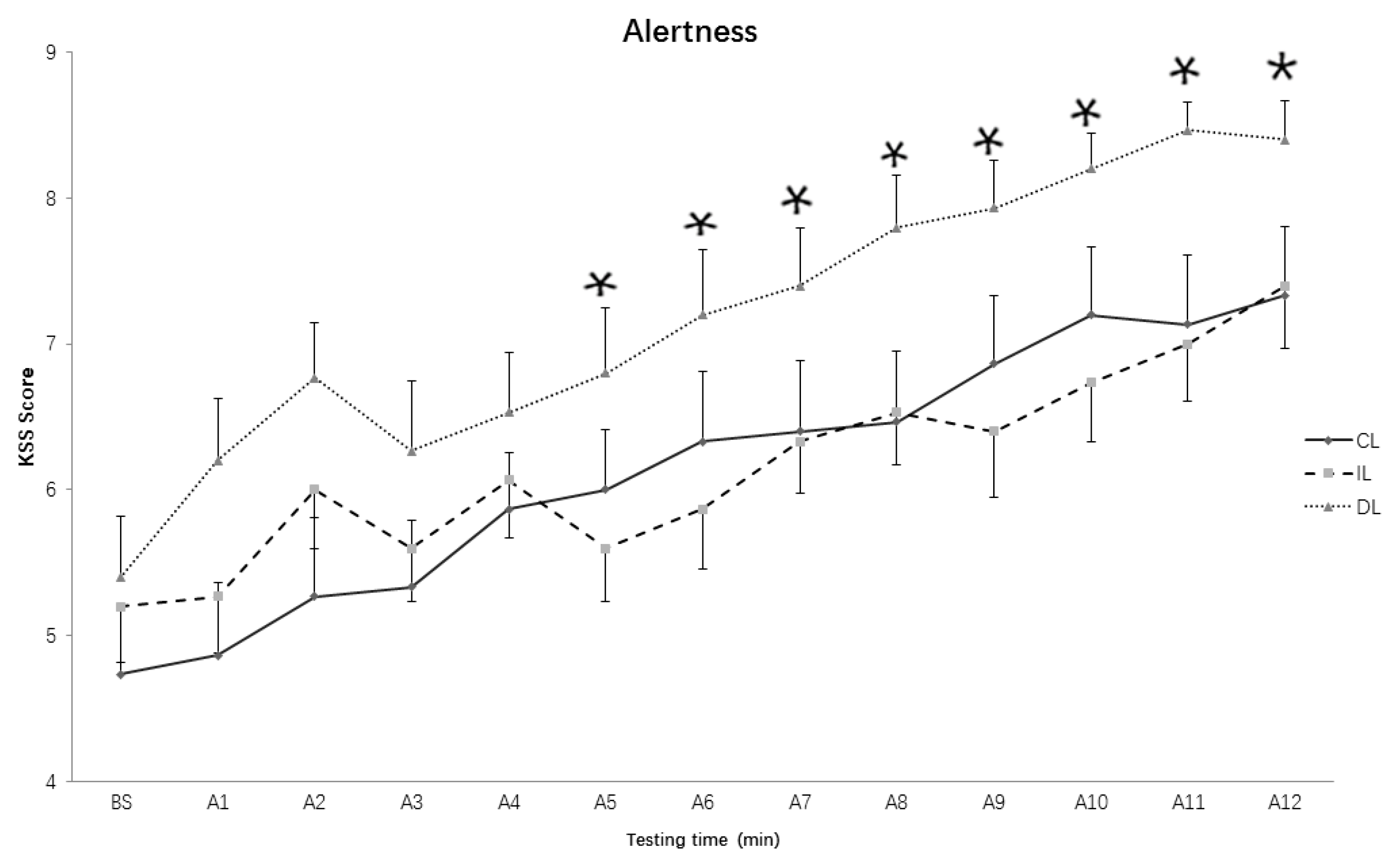

3.1. Subjective Alertness

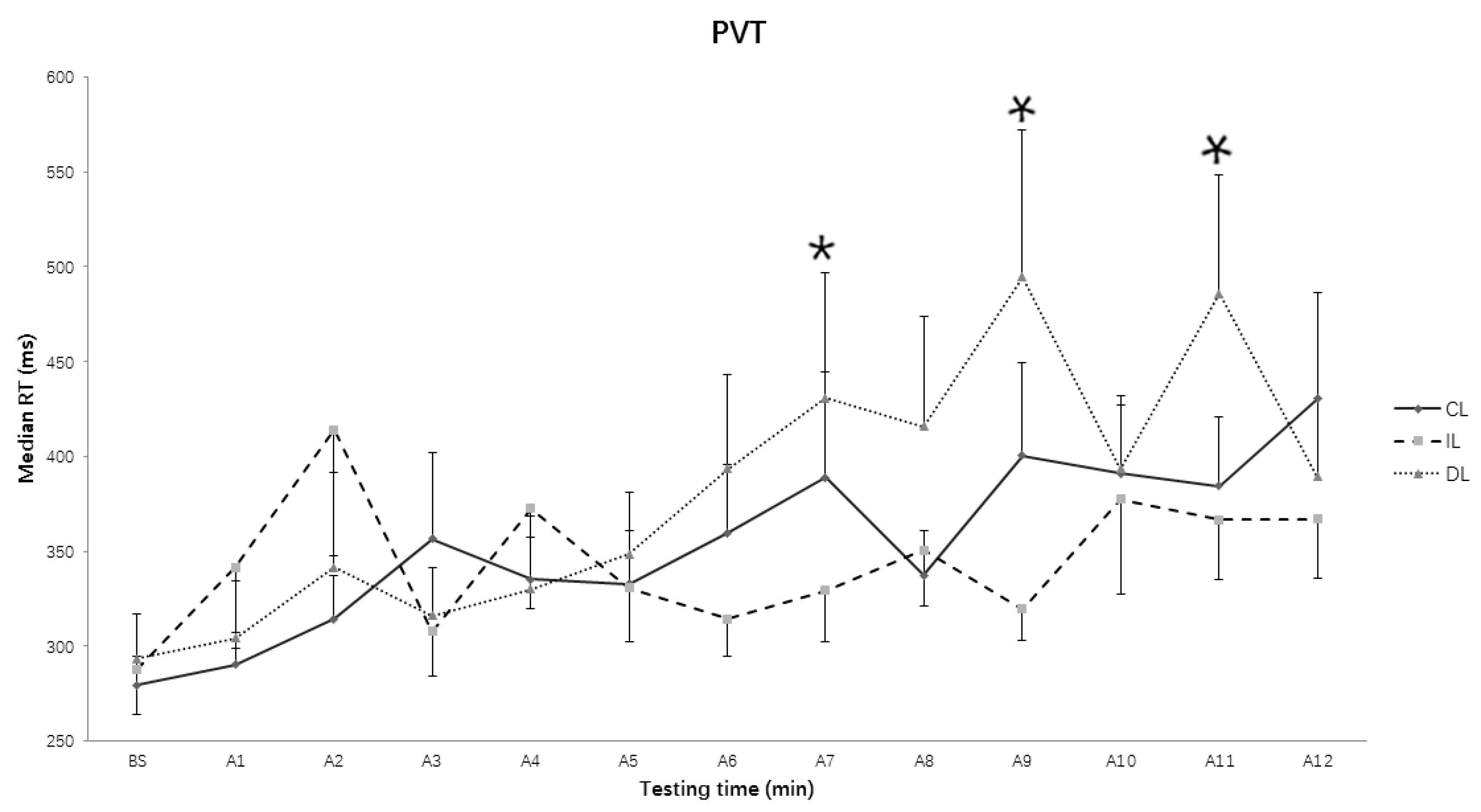

3.2. Median Reaction Time (RT) in Psychomotor Vigilance Task (PVT)

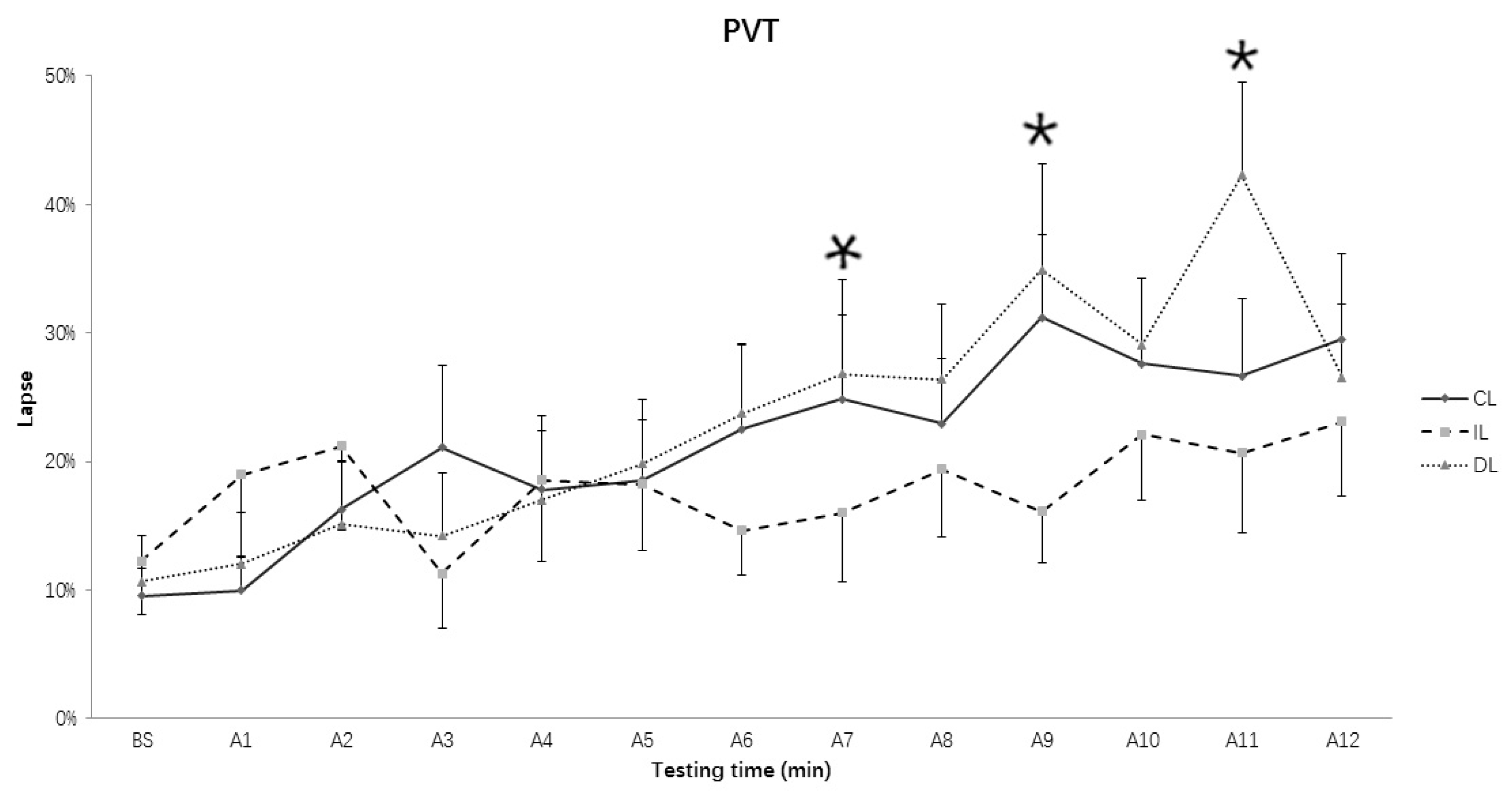

3.3. Lapses of RT in PVT

3.4. Sleep Structure

3.5. Total Sleep Time (TST)

3.6. Sleep Efficiency (SE)

3.7. Time in Bed (TIB) and Ratio of Different Sleep Stages

3.8. Rapid Eye Movement (REM) Sleep Latency from Sleep Onset

3.9. Sleep Onset Latency (SOL)

3.10. Wake after Sleep Onset (WASO)

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- LeGates, T.A.; Fernandez, D.C.; Hattar, S. Light as a central modulator of circadian rhythms, sleep and affect. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 15, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattar, S.; Kumar, M.; Park, A.; Tong, P.; Tung, J.; Yau, K.W.; Berson, D.M. Central projections of melanopsin-expressing retinal ganglion cells in the mouse. J. Comp. Neurol. 2010, 497, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirjam, M.; Vivien, B. Light and chronobiology: Implications for health and disease. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 14, 448–453. [Google Scholar]

- Gooley, J.J.; Lu, J.; Chou, T.C.; Scammell, T.E.; Saper, C.B. Melanopsin in cells of origin of the retinohypothalamic tract. Nat. Neurosci. 2001, 4, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revell, V.L.; Arendt, J.; Fogg, L.F.; Skene, D.J. Alerting effects of light are sensitive to very short wavelengths. Neurosci. Lett. 2006, 399, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.A.; Schoen, M.W.; Czeisler, C.A. Adaptation of human pineal melatonin suppression by recent photic history. J. Clin. Endocr. Metab. 2004, 89, 3610–3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berson, D.M.; Dunn, F.A.; Takao, M. Phototransduction by retinal ganglion cells that set the circadian clock. Science 2002, 295, 1070–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruby, N.F.; Brennan, T.J.; Xie, X.; Cao, V.; Franken, P.; Heller, H.C.; O’Hara, B.F. Role of melanopsin in circadian responses to light. Science 2002, 298, 2211–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupi, D.; Oster, H.; Thompson, S.; Foster, R.G. The acute light-induction of sleep is mediated by OPN4-based photoreception. Nat. Neurosci. 2008, 11, 1068–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, S.A.; St. Hilaire, M.A.; Lockley, S.W. The effects of spectral tuning of evening ambient light on melatonin suppression, alertness and sleep. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 177, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiro, M.G.; Nagare, R.; Price, L.L.A. Non-visual effects of light: How to use light to promote circadian entrainment and elicit alertness. Light. Res. Technol. 2018, 50, 38–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Lang, C.P. Revisiting the alerting effect of light: A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souman, J.L.; Tinga, A.M.; Te Pas, S.F.; van Ee, R.; Vlaskamp, B.N.S. Acute alerting effects of light: A systematic literature review. Behav. Brain Res. 2018, 337, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, S.A.; Flynnevans, E.E.; Aeschbach, D.; Brainard, G.C.; Czeisler, C.A.; Lockley, S.W. Diurnal spectral sensitivity of the acute alerting effects of light. Sleep 2014, 37, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinges, D.F.; Powell, J.W. Microcomputer analyses of performance on a portable, simple visual RT task during sustained operations. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 1985, 17, 652–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajochen, C. Alerting effects of light. Sleep Med. Rev. 2007, 11, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolders, K.C.H.J.; de Kort, Y.A.W.; Cluitmans, P.J.M. A higher illuminance induces alertness even during office hours: Findings on subjective measures, task performance and heart rate measures. Physiol. Behav. 2012, 107, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockley, S.W.; Evans, E.E.; Scheer, F.A.; Brainard, G.C.; Czeisler, C.A.; Aeschbach, D. Short-wavelength sensitivity for the direct effects of light on alertness, vigilance, and the waking electroencephalogram in humans. Sleep 2006, 29, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Motamedzadeh, M.; Golmohammadi, R.; Kazemi, R.; Heidarimoghadam, R. The effect of blue-enriched white light on cognitive performances and sleepiness of night-shift workers: A field study. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 177, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrin, F.; Peigneux, P.; Fuchs, S.; Verhaeghe, S.; Laureys, S.; Middleton, B.; Degueldre, C.; Del Fiore, G.; Vandewalle, G.; Balteau, E. Nonvisual responses to light exposure in the human brain during the circadian night. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, 1842–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandewalle, G.; Maquet, P.; Dijk, D.J. Light as a modulator of cognitive brain function. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2009, 13, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandewalle, G.; Balteau, E.; Phillips, C.; Degueldre, C.; Moreau, V.; Sterpenich, V.; Albouy, G.; Darsaud, A.; Desseilles, M.; Dang-Vu, T.T. Daytime light exposure dynamically enhances brain responses. Curr. Biol. 2006, 16, 1616–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandewalle, G.; Gais, S.; Schabus, M.; Balteau, E.; Carrier, J.; Darsaud, A.; Sterpenich, V.; Albouy, G.; Dijk, D.J.; Maquet, P. Wavelength-dependent modulation of brain responses to a working memory task by daytime light exposure. Cereb. Cortex. 2007, 17, 2788–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijk, D.J.; Visscher, C.A.; Bloem, G.M.; Beersma, D.G.; Daan, S. Reduction of human sleep duration after bright light exposure in the morning. Neurosci. Lett. 1987, 73, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrier, J.; Dumont, M. Sleep propensity and sleep architecture after bright light exposure at three different times of day. J. Sleep Res. 1995, 4, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drennan, M.; Kripke, D.F.; Gillin, J.C. Bright light can delay human temperature rhythm independent of sleep. Am. J. Physiol. 1989, 257, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Münch, M.; Kobialka, S.; Steiner, R.; Oelhafen, P.; Wirzjustice, A.; Cajochen, C. Wavelength-dependent effects of evening light exposure on sleep architecture and sleep EEG power density in men. Am. J. Physiol. Reg. I. 2006, 290, R1421–R1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, A.; Aeschbach, D.; Duffy, J.F.; Czeisler, C.A. Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 1232–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gronfier, C.; Wright, K.P.; Kronauer, R.E.; Jewett, M.E.; Czeisler, C.A. Efficacy of a single sequence of intermittent bright light pulses for delaying circadian phase in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 287, E174–E181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, H.J.; Crowley, S.J.; Gazda, C.J.; Fogg, L.F.; Eastman, C.I. Preflight adjustment to eastward travel: 3 days of advancing sleep with and without morning bright light. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2003, 18, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iskra-Golec, I.; Smith, L. Daytime intermittent bright light effects on processing of laterally exposed stimuli, mood, and light perception. Chronobiol. Int. 2008, 25, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iskra-Golec, I.; Smith, L. Bright light effects on ultradian rhythms in performance on hemisphere-specific tasks. Appl. Ergon. 2011, 42, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hébert, M.; Dumont, M.; Paquet, J. Seasonal and diurnal patterns of human illumination under natural conditions. Chronobiol. Int. 1998, 15, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okudaira, N.; Kripke, D.F.; Webster, J.B. Naturalistic studies of human light exposure. Am. J. Physiol. 1983, 245, R613–R615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimmer, D.W.; Boivin, D.B.; Shanahan, T.L.; Kronauer, R.E.; Duffy, J.F.; Czeisler, C.A. Dynamic resetting of the human circadian pacemaker by intermittent bright light. Am. J. Physiol. Reg. I. 2000, 279, R1574–R1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savides, T.J.; Messin, S.; Senger, C.; Kripke, D.F. Natural light exposure of young adults. Physiol. Behav. 1986, 38, 571–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czeisler, C.A.; Wright, K.P. Influence of light on circadian rhythmicity in humans. In Regulation of Sleep and Circadian Rhythms; Turek, F.W., Zee, P.C., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 149–180. [Google Scholar]

- Horne, J.A.; Östberg, O. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int. J. Chronobiol. 1976, 4, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buysse, D.J.; Rd, R.C.; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G. The Beck Depression Inventory-II; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T.; Epstein, N.; Brown, G.; Steer, R.A. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1988, 56, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, R.J.; Peirson, S.N.; Berson, D.M.; Brown, T.M.; Cooper, H.M.; Czeisler, C.A.; Figueiro, M.G.; Gamlin, P.D.; Lockley, S.W.; O’Hagan, J.B. Measuring and using light in the melanopsin age. Trends Neurosci. 2014, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chellappa, S.L.; Steiner, R.; Oelhafen, P.; Lang, D.; Götz, T.; Krebs, J.; Cajochen, C. Acute exposure to evening blue-enriched light impacts on human sleep. J. Sleep Res. 2013, 22, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, C.M.; Ronda, J.M.; Czeisler, C.A.; Wright, K.P.J. Comparison of sustained attention assessed by auditory and visual psychomotor vigilance tasks prior to and during sleep deprivation. J. Sleep Res. 2011, 20, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dongen, H.P.A.; Maislin, G.; Mullington, J.; Dinges, D.F. The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: Dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from Chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation. Sleep 2003, 26, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doran, S.M.; Van Dongen, H.P.A.; Dinges, D.F. Sustained attention performance during sleep deprivation: Evidence of state instability. Arch. Ital. Biol. 2001, 139, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Åkerstedt, T.; Gillberg, M. Subjective and objective sleepiness in the active individual. Int. J. Neurosci. 1990, 52, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hommes, V.; Giménez, M.C. A revision of existing Karolinska Sleepiness Scale responses to light: A melanopic perspective. Chronobiol. Int. 2015, 32, 750–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaida, K.; Takahashi, M.; Åkerstedt, T.; Nakata, A.; Otsuka, Y.; Haratani, T.; Fukasawa, K. Validation of the Karolinska sleepiness scale against performance and EEG variables. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2006, 117, 1574–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cajochen, C.; Brunner, D.P.; Kräuchi, K.; Graw, P.; Wirz-Justice, A. EEG and subjective sleepiness during extended wakefulness in seasonal affective disorder: Circadian and homeostatic influences. Biol. Psychiatry 2000, 47, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kecklund, G.; Åkerstedt, T. Sleepiness in long distance truck driving: An ambulatory EEG study of night driving. Ergonomics 1993, 36, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phipps-Nelson, J.; Redman, J.R.; Schlangen, L.J.; Rajaratnam, S.M. Blue light exposure reduces objective measures of sleepiness during prolonged nighttime performance testing. Chronobiol. Int. 2009, 26, 891–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyatt, J.K.; Cecco, A.R.; Czeisler, C.A.; Dijk, D. Circadian temperature and melatonin rhythms, sleep, and neurobehavioral function in humans living on a 20-h day. Am. J. Physiol. 1999, 277, R1152–R1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AOSM. International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd ed.; AOSM: Darien, CT, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dacey, D.M.; Liao, H.W.; Peterson, B.B.; Robinson, F.R.; Smith, V.C.; Pokorny, J.; Yau, K.W.; Gamlin, P.D. Melanopsin-expressing ganglion cells in primate retina signal colour and irradiance and project to the LGN. Nature 2005, 433, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najjar, R.P.; Zeitzer, J.M. Temporal integration of light flashes by the human circadian system. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolders, K.C.H.J.; de Kort, Y.A.W. Bright light and mental fatigue: Effects on alertness, vitality, performance and physiological arousal. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 39, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.M.; Santhi, N.; St, H.M.; Gronfier, C.; Bradstreet, D.S.; Duffy, J.F.; Lockley, S.W.; Kronauer, R.E.; Czeisler, C.A. Human responses to bright light of different durations. J. Physiol. 2012, 590, 3103–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavie, P. Sleep-wake as a biological rhythm. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 277–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.R.; Joo, E.Y.; Koo, D.L.; Hong, S.B. Let there be no light: The effect of bedside light on sleep quality and background electroencephalographic rhythms. Sleep Med. 2013, 14, 1422–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, C.H.; Lee, H.J.; Yoon, H.K.; Kang, S.G.; Bok, K.N.; Jung, K.Y.; Kim, L.; Lee, E.I. Exposure to dim artificial light at night increases REM sleep and awakenings in humans. Chronobiol. Int. 2016, 33, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowley, S.J.; Lee, C.; Tseng, C.Y.; Fogg, L.F.; Eastman, C.I. Combinations of bright light, scheduled dark, sunglasses, and melatonin to facilitate circadian entrainment to night shift work. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2003, 18, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohayon, M.M. Epidemiology of insomnia: What we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med. Rev. 2002, 6, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sensitivity | λmax (nm) | α-Opic Lux Value (~5 Lux) | α-Opic Lux Value (~1000 Lux) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melanopsin | 480.0 | 2.27 | 870.70 |

| S-cone | 419.0 | 1.46 | 911.50 |

| M-cone | 530.8 | 3.98 | 939.15 |

| L-cone | 558.4 | 4.45 | 920.03 |

| Rods | 496.3 | 2.92 | 903.13 |

| Stages | IL | CL | DL | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIB (min) | 393.9 ± 17.0 | 392.3 ± 16.2 | 404.1 ± 13.8 | 0.619 | 0.546 | 0.042 |

| TST (min) | 363 ± 15.9 | 368.4 ± 15.0 | 387.5 ± 13.3 | 4.473 | 0.045 | 0.199 |

| SOL (min) | 13.1 ± 3.7 | 9.6 ± 1.8 | 4.4 ± 0.7 | 3.782 | 0.063 | 0.213 |

| RL (min) | 69.1 ± 7.1 | 81.4 ± 7.6 | 66.7 ± 3.2 | 2.332 | 0.116 | 0.143 |

| SE (%) | 92.3 ± 1.4 | 94.0 ± 0.8 | 95.9 ± 0.4 | 3.894 | 0.049 | 0.218 |

| N1 (%) | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 4.4 ± 0.9 | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 0.131 | 0.878 | 0.009 |

| N2 (%) | 55.6 ± 1.5 | 56.3 ± 1.3 | 54.9 ± 1.8 | 0.583 | 0.565 | 0.040 |

| N3 (%) | 16.0 ± 1.6 | 16.7 ± 1.7 | 16.6 ± 1.2 | 0.156 | 0.865 | 0.011 |

| REM (%) | 24.1 ± 1.3 | 22.6 ± 1.2 | 24.5 ± 1.2 | 1.099 | 0.347 | 0.073 |

| WASO (%) | 5.2 ± 1.1 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 4.800 | 0.077 | 0.286 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, M.; Ma, N.; Zhu, Y.; Su, Y.-C.; Chen, Q.; Hsiao, F.-C.; Ji, Y.; Yang, C.-M.; Zhou, G. The Acute Effects of Intermittent Light Exposure in the Evening on Alertness and Subsequent Sleep Architecture. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030524

Yang M, Ma N, Zhu Y, Su Y-C, Chen Q, Hsiao F-C, Ji Y, Yang C-M, Zhou G. The Acute Effects of Intermittent Light Exposure in the Evening on Alertness and Subsequent Sleep Architecture. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(3):524. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030524

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Minqi, Ning Ma, Yingying Zhu, Ying-Chu Su, Qingwei Chen, Fan-Chi Hsiao, Yanran Ji, Chien-Ming Yang, and Guofu Zhou. 2018. "The Acute Effects of Intermittent Light Exposure in the Evening on Alertness and Subsequent Sleep Architecture" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 3: 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030524

APA StyleYang, M., Ma, N., Zhu, Y., Su, Y.-C., Chen, Q., Hsiao, F.-C., Ji, Y., Yang, C.-M., & Zhou, G. (2018). The Acute Effects of Intermittent Light Exposure in the Evening on Alertness and Subsequent Sleep Architecture. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(3), 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030524