Preparedness of Health Care Professionals for Delivering Sexual and Reproductive Health Care to Refugee and Migrant Women: A Mixed Methods Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

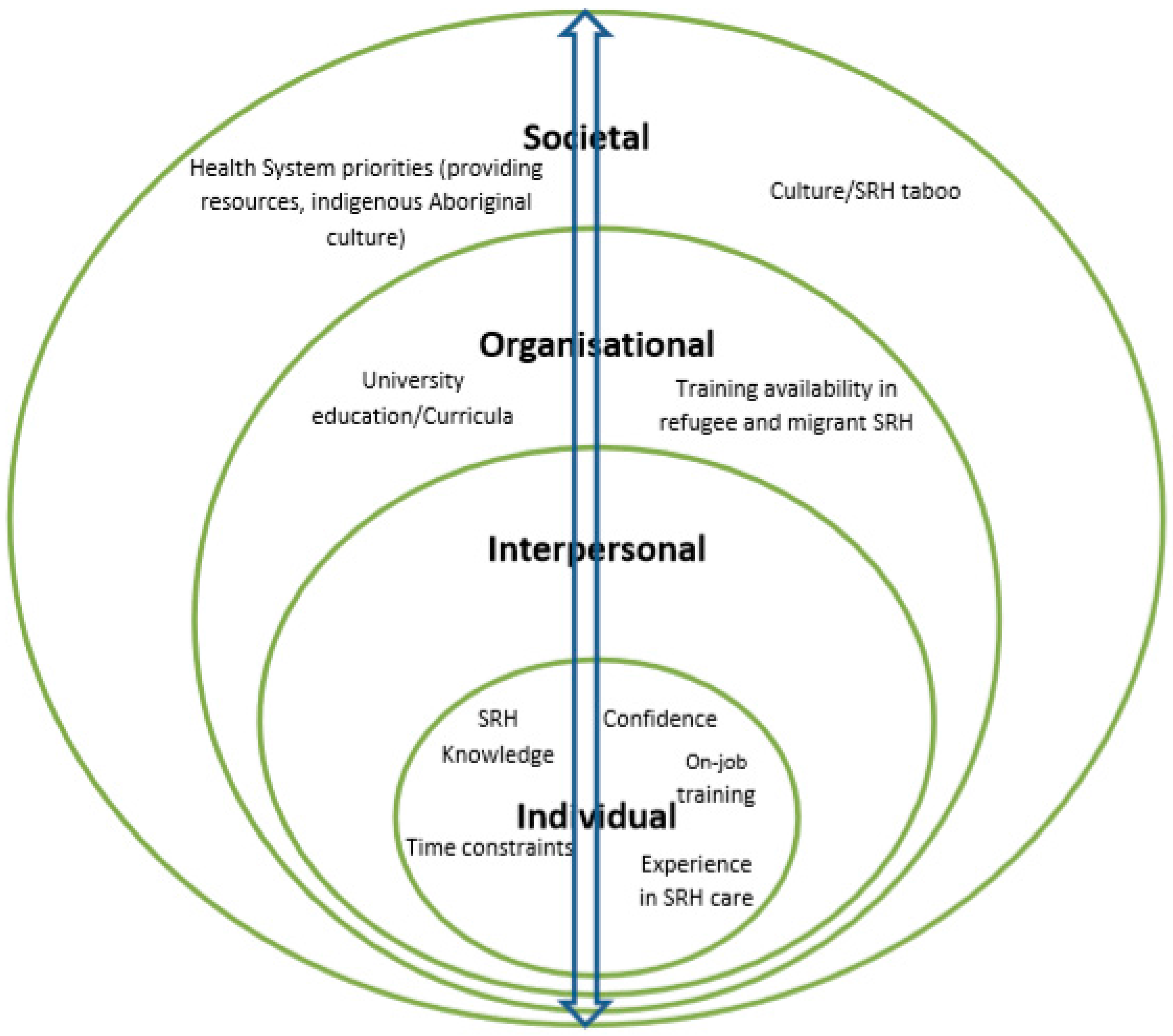

Theoretical Approach

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.2.1. Survey

2.2.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

2.3. Operational Definitions

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Knowledge and Confidence: “Providers Don’t Want to Deal with It or They Can’t Deal with It”

Broaching the subject is the challenge I face because lots of women tell you “oh, I don’t want to talk about it.” So it’s a challenge to be able to break that barrier to let them know that it’s important to talk about what’s going on because you need to help them in regards to not having any problem now or in the future.(Alice, GP, 35)

Hell, the majority of them (HCPs) can’t do (talk about) sexual and reproductive health to these women…You can’t sit there and giggle and say, “oh I’m sorry I’ve got to ask you a personal question.” The challenge is getting them (the women) to bring it up as they are not going to say “I have got a discharge.”

“I have worked in sexual health for a long time. So to me it’s no different to addressing the health of their eyes or their lungs or their feet or anything else. There is no cultural group that I can’t discuss these (sexual health) issues with.”(Amy, nurse, 17)

“Generally no one likes talking about that area of their health. So the way I do it is prepare them first, that I would like to ask them these questions, and give them a benefit to answering those questions for themselves. So for example, I ask this for your health. I want to make sure you’re all right. There is a positive in it for them.”(Amy, nurse, 17)

3.2. Training Experiences and Needs: Moving across Levels of Influence

“There is now a huge push for us to learn about the Aboriginal culture and it’s become mandatory that we do some of the training on that. But there’s nothing really to—along similar lines to educate us about these other cultures and about some of the traumas and such that people go through.”(Grace, nurse, 13)

“So time constraint is a big issue for health professionals. Because they’re always short of time, I think that they don’t spend the time or don’t put the time aside to do extra training in terms of sexual and reproductive health care, and when training does come up, often they can’t go because they’re so short of time, or because they just don’t want to do it because it’s too hard.”(Amy, nurse, 17)

“Sometimes you can be having a consultation—it’s all going well, and then something just changes. I think I would really like to know why in some of those cases. Some of them you can sit back and think, oh, I shouldn’t have said that or I should have said this differently, or I should have backed off and asked that in a different way. I think having increased knowledge helps to do that sort of analysis afterwards.”(Chloe, nurse, 13)

“I guess that’s the same for even potentially medical receptionists as well, because if a woman misses her appointments a couple of times, or comes extremely late for an appointment, sometimes that can be quite frustrating for receptionists who have to re-book their appointments, yet they don’t actually understand the reasons why that might be occurring.”(Kokob, health promotion officer, 8)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Phillips, C.B.; Travaglia, J. Low levels of uptake of free interpreters by Australian doctors in private practice: Secondary analysis of national data. Aust. Health Rev. 2011, 35, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alpern, J.D.; Davey, C.S.; Song, J. Perceived barriers to success for resident physicians interested in immigrant and refugee health. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudelson, P.; Perron, N.J.; Perneger, T.V. Measuring physicians’ and medical students’ attitudes toward caring for immigrant patients. Eval. Health Prof. 2010, 33, 452–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez Navarrete, M.L.; Terraza Núñez, R.; Vargas Lorenzo, I.; Lizana Alcazo, T. Perceived needs of health personnel in the provision of healthcare to the immigrant population. Gac. Sanit. 2009, 23, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papic, O.; Malak, Z.; Rosenberg, E. Survey of family physicians’ perspectives on management of immigrant patients: Attitudes, barriers, strategies, and training needs. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 86, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmsen, H.; Meeuwesen, L.; van Wieringen, J.; Bernsen, R.; Bruijnzeels, M. When cultures meet in general practice: Intercultural differences between GPs and parents of child patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2003, 51, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieper, H.-O.; MacFarlane, A. I’m worried about what I missed: GP Registrars’ Views on Learning Needs to Deliver Effective Healthcare to Ethnically and Culturally Diverse Patient Populations. Educ. Health 2011, 24, 494. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, S.; Gama, A.; Cargaleiro, H.; Martins, M.O. Health workers’ attitudes toward immigrant patients: A cross-sectional survey in primary health care services. Hum. Resour. Health 2012, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, J. Sexual and gender-based violence against refugee women: A hidden aspect of the refugee “crisis”. Reprod. Health Matters 2016, 24, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keygnaert, I.; Vettenburg, N.; Temmerman, M. Hidden violence is silent rape: Sexual and gender-based violence in refugees, asylum seekers and undocumented migrants in Belgium and The Netherlands. Cult. Health Sex. 2012, 14, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The United Nations Children’s Fund. Sexual and Gender-Based Violence against Refugees, Returnees and Internally Displaced Persons-Guidelines for Prevention and Response; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, J.; Guy, S.; Lee-Jones, L.; McGinn, T.; Schlecht, J. Reproductive health: A right for refugees and internally displaced persons. Reprod. Health Matters 2008, 16, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussher, J.M.; Perz, J.; Metusela, C.; Hawkey, A.J.; Morrow, M.; Narchal, R.; Estoesta, J. Negotiating Discourses of Shame, Secrecy, and Silence: Migrant and Refugee Women’s Experiences of Sexual Embodiment. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2017, 46, 1901–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metusela, C.; Ussher, J.; Perz, J.; Hawkey, A.; Morrow, M.; Narchal, R.; Estoesta, J.; Monteiro, M. In My Culture, We Don’t Know Anything about That: Sexual and Reproductive Health of Migrant and Refugee Women. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2017, 24, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengesha, Z.; Perz, J.; Dune, T.; Ussher, J. Refugee and migrant women’s engagement with sexual and reproductive health care in Australia: A socio-ecological analysis of health care professional perspectives. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utting, S.; Calcutt, C.; Marsh, K.; Doherty, P. Women and Sexual and Reproductive Health; Australian Women’s Health Network: Drysdale, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, K.; Abbott, P.; Reath, J. Cross-cultural training of general practitioner registrars: How does it happen? Aust. J. Prim. Health 2016, 22, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watt, K.; Abbott, P.; Reath, J. Cultural competency training of GP Registrars-exploring the views of GP Supervisors. Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suphanchaimat, R.; Kantamaturapoj, K.; Putthasri, W.; Prakongsai, P. Challenges in the provision of healthcare services for migrants: A systematic review through providers’ lens. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newbold, K.B.; Willinsky, J. Providing family planning and reproductive healthcare to Canadian immigrants: Perceptions of healthcare providers. Cult. Health Sex. 2009, 11, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degni, F.; Suominen, S.; Essen, B.; El Ansari, W.; Vehvilainen-Julkunen, K. Communication and cultural issues in providing reproductive health care to immigrant women: Health care providers’ experiences in meeting the needs of (corrected) Somali women living in Finland. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2012, 14, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons, S.M.; O’Keeffe, F.M.; Clarke, A.T.; Staines, A. Cultural diversity in the Dublin maternity services: The experiences of maternity service providers when caring for ethnic minority women. Ethn. Health 2008, 13, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, C.; Newbold, K.B. Health care providers’ perspectives on the provision of prenatal care to immigrants. Cult. Health Sex. 2011, 13, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobin, C.L.; Murphy-Lawless, J. Irish midwives’ experiences of providing maternity care to non-Irish women seeking asylum. Int. J. Women's Health 2014, 6, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruitt, S.D.; Epping-Jordan, J.E. Preparing the 21st century global healthcare workforce. BMJ 2005, 330, 637–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Am. Psychol. 1979, 32, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Collins, K.M.; Frels, R.K. Foreword: Using Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory to frame quantitative, qualitative, and mixed research. Int. J. Mult. Res. Approaches 2013, 7, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Klassen, A.C.; Plano Clark, V.L.; Smith, K.C. Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences; National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2011; pp. 2094–2103.

- Ivankova, N.V.; Creswell, J.W.; Stick, S.L. Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: From theory to practice. Field Methods 2006, 18, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilpinen, R. Knowing that one knows and the classical definition of knowledge. Synthese 1970, 21, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confidence in Psychology Today. 2017. Available online: https://www.psychologytoday.com/basics/confidence (accessed on 17 August 2017).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengesha, Z.; Perz, J.; Dune, T.; Ussher, J. Challenges in the provision of sexual and reproductive health care to refugee and migrant women: A Q methodological study of health professional perspectives. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Increasing Cultural Competency for Healthier Living & Environments: Discussion Paper; National Health and Medical Research Council: Canberra, Australia, 2005.

- Whelan, A.M. Consultation with non-English speaking communities: Rapid bilingual appraisal. Aust. Health Rev. 2004, 28, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Cultural Competency in Health: A Guide for Policy, Partnerships and Participation; National Health and Medical Research Council: Canberra, Australia, 2006.

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners Curriculum for Australian General Practice; Multicultural Health: Melbourne, Australia, 2011.

- Kurth, E.; Jaeger, F.N.; Zemp, E.; Tschudin, S.; Bischoff, A. Reproductive health care for asylum-seeking women—A challenge for health professionals. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengesha, Z.; Dune, T.; Perz, J. Culturally and linguistically diverse women’s views and experiences of accessing sexual and reproductive health care in Australia: A systematic review. Sex. Health 2016, 13, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ussher, J.M.; Perz, J.; Gilbert, E.; Wong, W.K.; Mason, C.; Hobbs, K.; Kirsten, L. Talking about sex after cancer: A discourse analytic study of health care professional accounts of sexual communication with patients. Psychol. Health 2013, 28, 1370–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischoff, A.; Perneger, T.V.; Bovier, P.A.; Loutan, L.; Stalder, H. Improving communication between physicians and patients who speak a foreign language. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2003, 53, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hatch, M. Common Threads: The Sexual and Reproductive Health Experiences of Immigrant and Refugee Women in Australia; MCWH: Melbourne, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Women | 76 | 96.2 |

| Men | 3 | 3.8 | |

| Occupation | Nurse/Midwife | 36 | 45.6 |

| GP | 24 | 30.3 | |

| Health promotion officer * | 13 | 16.5 | |

| Allied health professionals ** | 6 | 7.6 | |

| Work experience in years | 1–10 | 33 | 41.8 |

| 11–20 | 25 | 31.6 | |

| 21 and above | 21 | 26.6 | |

| Refugee and migrant women seen daily | 0 | 27 | 34.1 |

| 1–5 | 46 | 58.2 | |

| >6 | 6 | 7.7 | |

| SRH services refugee and migrant women commonly accessed | Contraception | 51 | 64.56 |

| Pregnancy related (Antenatal care, delivery and postnatal care) | 33 | 41.77 | |

| Abortion | 29 | 36.71 | |

| Sexually transmitted infections (Information, screening and treatment) | 29 | 36.71 | |

| Screening (Chlamydia and Cervical cytology) | 36 | 45.57 | |

| Infertility | 32 | 40.51 | |

| Safer sex options | 17 | 21.52 | |

| Sexual pain and discomfort | 30 | 37.97 | |

| Sexual violence and unwanted sex | 17 | 21.52 | |

| Background of women seen | Afghanistan | 31 | 41.33 |

| Iran | 30 | 40 | |

| Sudan | 30 | 40 | |

| Iraq | 29 | 38.67 | |

| Myanmar/Burma | 19 | 25.33 | |

| Somalia | 18 | 24 | |

| Bhutan | 6 | 8 | |

| Congo (DRC) | 6 | 8 | |

| Others *** | 36 | 48 | |

| Variable | Occupation | Test of Group Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse | GP | HPO | χ2 | p | ||

| Knowledge | Very low/low | 10 (27.8%) | 5 (20.8%) | 4 (30.8%) | 2.04 | 0.73 |

| Moderate | 15 (41.7%) | 13 (54.2%) | 4 (30.8%) | |||

| High | 11 (30.6%) | 6 (25.0%) | 5 (30.8%) | |||

| Confidence | Very low/low | 7 (19.4%) | 3 (12.5%) | 2 (15.4%) | 1.95 | 0.74 |

| Moderate | 18 (50.0%) | 14 (58.3%) | 5 (38.5%) | |||

| High | 11 (30.6%) | 7 (29.2%) | 6 (46.2%) | |||

| Previous training | Yes | 11 (30.6%) | 12 (50%) | 8 (61.5%) | 4.58 | 0.10 |

| No | 25 (69.4%) | 12 (50%) | 5 (38.5%) | |||

| Need for further training | Yes | 32 (88.9%) | 18 (75%) | 10 (76.9%) | 2.04 | 0.33 |

| No | 4 (11.1%) | 6 (25%) | 23.1%) | |||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mengesha, Z.B.; Perz, J.; Dune, T.; Ussher, J. Preparedness of Health Care Professionals for Delivering Sexual and Reproductive Health Care to Refugee and Migrant Women: A Mixed Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15010174

Mengesha ZB, Perz J, Dune T, Ussher J. Preparedness of Health Care Professionals for Delivering Sexual and Reproductive Health Care to Refugee and Migrant Women: A Mixed Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(1):174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15010174

Chicago/Turabian StyleMengesha, Zelalem B., Janette Perz, Tinashe Dune, and Jane Ussher. 2018. "Preparedness of Health Care Professionals for Delivering Sexual and Reproductive Health Care to Refugee and Migrant Women: A Mixed Methods Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 1: 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15010174

APA StyleMengesha, Z. B., Perz, J., Dune, T., & Ussher, J. (2018). Preparedness of Health Care Professionals for Delivering Sexual and Reproductive Health Care to Refugee and Migrant Women: A Mixed Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(1), 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15010174