Development and Validation of the Brief Folate-Specific Food Frequency Questionnaire for Young Women’s Diet Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Designing the Folate-Specific Food Frequency Questionnaire Fol-IC-FFQ (Folate-Intake Calculation-Food Frequency Questionnaire)

2.2. Validation of the Fol-IC-FFQ

2.3. Statistical Analysis

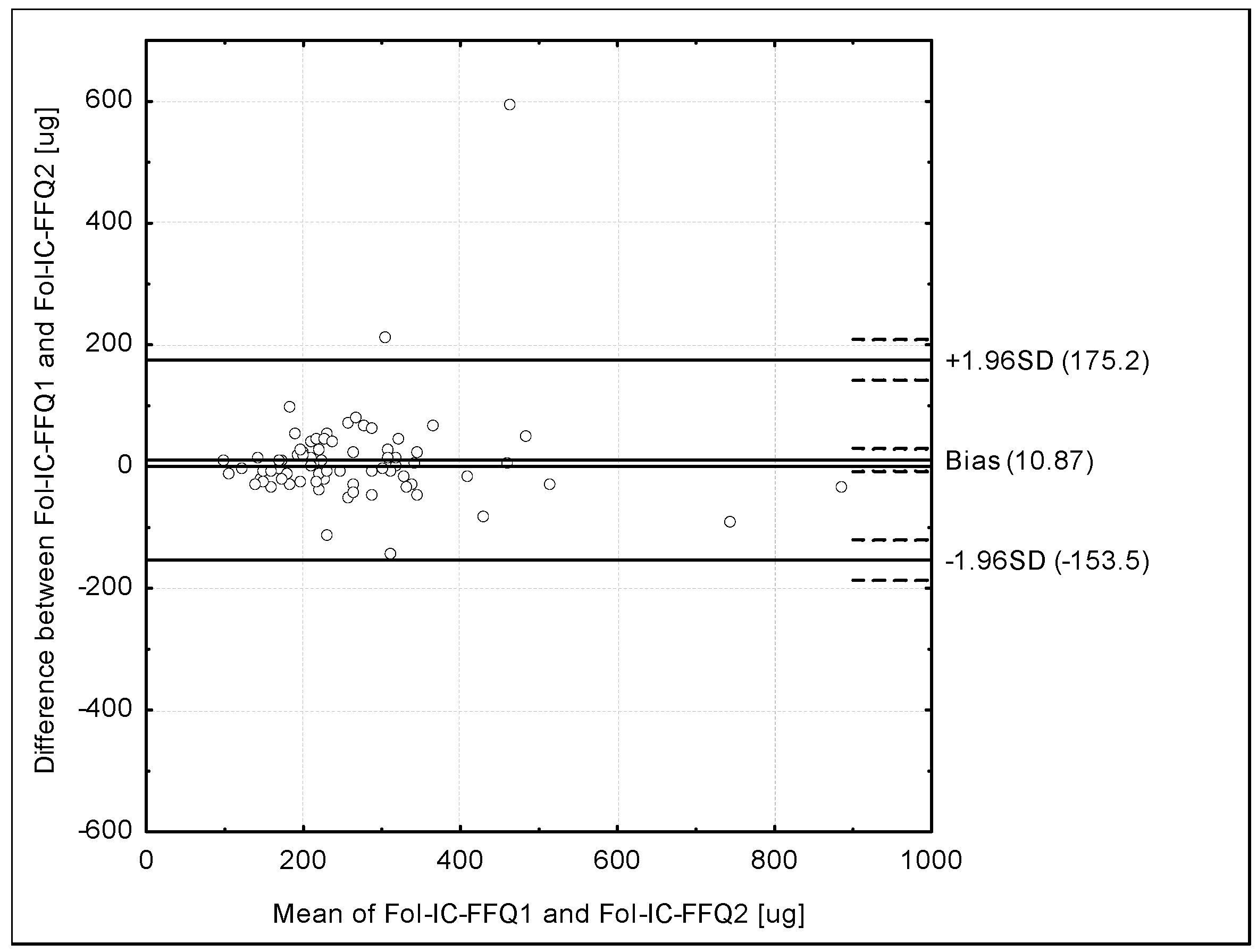

- Analysis of the Bland-Altman plots in the assessment of validity (Fol-IC-FFQ1 vs. 3-day record) and of reproducibility (Fol-IC-FFQ1 vs. Fol-IC-FFQ2): the results were interpreted using the Bland-Altman index, whereas the limits of agreement value (LOA) was calculated as the sum of the mean absolute differences of folate intake measured by the two methods, and the ± standard deviation of the absolute difference of folate intake recorded for the two methods magnified by 1.96. In the analysis conducted with the Bland-Altman method to assess agreement between the measurements, a Bland-Altman index of a maximum of 5% (95% of individuals observed to be within the LOA) was interpreted, as commonly assumed [37], as positive validation of the method of measurement.

- Assessment of the share of individuals classified into the same tertile and misclassified (classified into opposite tertiles) in the assessment of validity (Fol-IC-FFQ1 vs. 3-day record) and of reproducibility (Fol-IC-FFQ1 vs. Fol-IC-FFQ2).

- Calculation of the weighted κ statistic with linear weighting to indicate the level of agreement between the classifications into tertiles in the assessment of validity (Fol-IC-FFQ1 vs. 3-day record) and of reproducibility (Fol-IC-FFQ1 vs. Fol-IC-FFQ2). According to the criteria of Landis & Koch [38], values <0.20 were treated as slight agreement, 0.21–0.40 as fair, 0.41–0.60 as moderate, 0.61–0.80 as substantial, and 0.81–1.0 as almost perfect agreement.

- Assessment of the share of individuals classified into the same category (both of either adequate or inadequate intake) and of the conflicting intake adequacy category (adequate intake and inadequate intake) in the assessment of validity (Fol-IC-FFQ1 vs. 3-day record) and of reproducibility (Fol-IC-FFQ1 vs. Fol-IC-FFQ2). Adequate intake was defined according to the Polish recommendations for women on the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) level as 320 µg [39], which was higher than the level of 250 µg indicated by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) [40] as the Average Requirement, but simultaneously this was the same as the EAR level recommended by the Institute of Medicine/National Academy of Medicine [41].

- Calculation of the root mean square errors of prediction (RMSEP) and median absolute percentage errors (MdAPE) of folate intake.

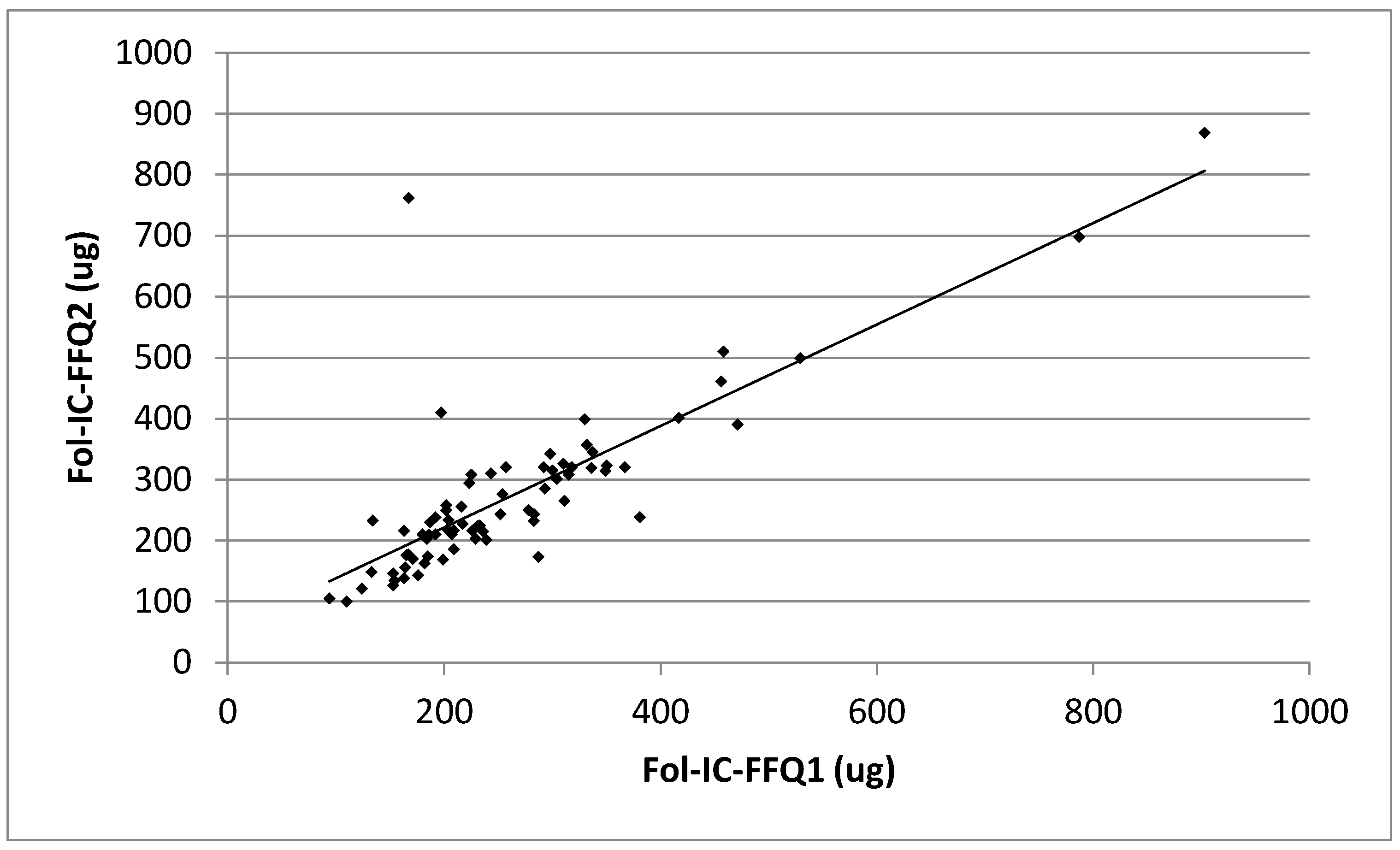

- Analysis of the correlations between results: the normality of distribution of the results was analyzed using the Shapiro-Wilk test and then Spearman’s rank correlation was applied for nonparametric distribution. Due to the nonparametric distribution, while data were presented, they were compared using the U Mann-Whitney test.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Optimal Serum and Red Blood Cell Folate Concentrations in Women of Reproductive Age for Prevention of Neural Tube Defects; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Intermittent Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation in Non-Anaemic Pregnant Women; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Nutrition Targets 2025, Policy Brief Series. WHO/NMH/NHD/14.2; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Peña-Rosas, J.P.; De-Regil, L.M.; Garcia-Casal, M.N.; Dowswell, T. Daily oral iron supplementation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, P.; Lee, S.E.; Donahue Angel, M.; Adair, L.S.; Arifeen, S.E.; Ashorn, P.; Barros, F.C.; Fall, C.H.; Fawzi, W.W.; Hao, W.; et al. Risk of childhood undernutrition related to small-for-gestational age and preterm birth in low- and middle-income countries. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 42, 1340–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. eLENA Interventions and Global Targets. Available online: http://www.who.int/elena/titles/targets/daily_iron_pregnancy/en/ (accessed on 10 October 2017).

- Meijer, W.M.; de Walle, H.E. Differences in folic-acid policy and the prevalence of neural-tube defects in Europe; recommendations for food fortification in a EUROCAT report. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 2005, 149, 2561–2564. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Manniën, J.; de Jonge, A.; Cornel, M.C.; Spelten, E.; Hutton, E.K. Factors associated with not using folic acid supplements preconceptionally. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 2344–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmermans, S.; Jaddoe, V.W.; Mackenbach, J.P.; Hofman, A.; Steegers-Theunissen, R.P.; Steegers, E.A. Determinants of folic acid use in early pregnancy in a multi-ethnic urban population in The Netherlands: The Generation R study. Prev. Med. 2008, 47, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinnunen, T.I.; Sletner, L.; Sommer, C.; Post, M.C.; Jenum, A.K. Ethnic differences in folic acid supplement use in a population-based cohort of pregnant women in Norway. PMC 2017, 17, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food Fortification Initiative. Available online: http://www.ffinetwork.org/country_profiles/index.php (accessed on 10 October 2017).

- Koren, G.; Goh, Y.I.; Klieger, C. Folic acid: The right dose. Can. Fam. Physician 2008, 54, 1545–1547. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilson, R.D.; Davies, G.; Désilets, V.; Reid, G.J.; Summers, A.; Wyatt, P.; Young, D. Genetics Committee and Executive and Council of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. The use of folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects and other congenital anomalies. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2003, 25, 959–973. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rinsky-Eng, J.; Miller, L. Knowledge, use, and education regarding folic acid supplementation: Continuation study of women in Colorado who had a pregnancy affected by a neural tube defect. Teratology 2002, 66, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedgh, G.; Singh, S.; Hussain, R. Intended and unintended pregnancies worldwide in 2012 and recent trends. Stud. Fam. Plan. 2014, 45, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bixenstine, P.J.; Cheng, T.L.; Cheng, D.; Connor, K.A.; Mistry, K.B. Folic acid supplementation before pregnancy: Reasons for non-use and association with preconception counseling. Matern. Child. Health J. 2015, 19, 1974–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zekovic, M.; Djekic-Ivankovic, M.; Nikolic, M.; Gurinovic, M.; Krajnovic, D.; Glibetic, M. Validity of the food frequency questionnaire assessing the folate intake in women of reproductive age Living in a country without food fortification: Application of the method of triads. Nutrients 2017, 13, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, I.; Van Guelpen, B.; Hultdin, J.; Johansson, M.; Hallmans, G.; Stattin, P. Validity of food frequency questionnaire estimated intakes of folate and other B vitamins in a region without folic acid fortification. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imbard, A.; Benoist, J.F.; Blom, H.J. Neural tube defects, folic acid and methylation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 17, 4352–4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayet, F.; Flood, V.; Petocz, P.; Samman, S. Relative and biomarker-based validity of a food frequency questionnaire that measures the intakes of vitamin B(12), folate, iron, and zinc in young women. Nutr. Res. 2011, 31, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; García-Arellano, A.; Toledo, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Buil-Cosiales, P.; Corella, D.; Covas, M.I.; Schröder, H.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; et al. A 14-item Mediterranean diet assessment tool and obesity indexes among high-risk subjects: The PREDIMED trial. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunachowicz, H.; Nadolna, J.; Przygoda, B.; Iwanow, K. (Eds.) Food Composition Tables; PZWL: Warsaw, Poland, 2005. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Finglas, P.; Weichselbaum, E.; Buttriss, J.L. The 3rd International EuroFIR Congress 2009: European food composition data for better diet, nutrition and food quality. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Głąbska, D.; Guzek, D.; Sidor, P.; Włodarek, D. Vitamin D dietary intake questionnaire validation conducted among young Polish women. Nutrients 2016, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Głąbska, D.; Guzek, D.; Ślązak, J.; Włodarek, D. Assessing the validity and reproducibility of an iron dietary intake questionnaire conducted in a group of young Polish women. Nutrients 2017, 9, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Głąbska, D.; Malowaniec, E.; Guzek, D. Validity and reproducibility of the iodine dietary intake questionnaire assessment conducted for young Polish women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czeczot, H. Folic acid in physiology and pathology. Postepy. Hig. Med. Dosw. 2008, 62, 405–419. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Sicińska, E.; Wyka, J. Folate intake in Poland on the basis of literature from last ten years (2000–2010). Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2011, 62, 247–256. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.Y.; Nicolas, G.; Freisling, H.; Biessy, C.; Scalbert, A.; Romieu, I.; Chajès, V.; Chuang, S.C.; Ericson, U.; Wallström, P.; et al. Comparison of standardised dietary folate intake across ten countries participating in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 552–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szponar, L.; Wolnicka, K.; Rychlik, E. Atlas of Food Products and Dishes Portion Sizes; IŻŻ: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Cade, J.; Thompson, R.; Burley, V.; Warm, D. Development, validation and utilisation of food-frequency questionnaires—A review. Public Health Nutr. 2002, 5, 567–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, W.; Lenart, E. Reproducibility and validity of food frequency questionnaires. In Nutritional Epidemilogy, 3rd ed.; Willett, W., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Colić Barić, I.; Satalić, Z.; Pedisić, Z.; Zizić, V.; Linarić, I. Validation of the folate food frequency questionnaire in vegetarians. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 60, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colić Barić, I.; Satalić, Z.; Keser, I.; Cecić, I.; Sucić, M. Validation of the folate food frequency questionnaire with serum and erythrocyte folate and plasma homocysteine. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 60, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brevik, A.; Vollset, S.E.; Tell, G.S.; Refsum, H.; Ueland, P.M.; Loeken, E.B.; Drevon, C.A.; Andersen, L.F. Plasma concentration of folate as a biomarker for the intake of fruit and vegetables: The Hordaland Homocysteine Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ortega, R.M.; Pérez-Rodrigo, C.; López-Sobaler, A.M. Dietary assessment methods: Dietary records. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 26, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Myles, P.S.; Cui, J. Using the Bland-Altman method to measure agreement with repeated measures. Br. J. Anaesth. 2007, 99, 309–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarosz, M. Human Nutrition Recommendations for Polish Population; IŻŻ: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Agostoni, C.; Canani, R.B.; Fairweather-Tait, S.; Heinonen, M.; Korhonen, H.; La Vieille, S.; Marchelli, R.; Martin, A.; Naska, A.; Neuhäuser-Berthold, M.; et al. EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies. Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for folate. EFSA J. 2014, 12, 3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otten, J.J.; Hellwig, J.P.; Meyers, L.D. Dietary Reference Intakes: The Essential Guide to Nutrient Requirements; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; p. 1344. [Google Scholar]

- Flood, V.M.; Smith, W.T.; Webb, K.L.; Mitchell, P. Issues in assessing the validity of nutrient data obtained from a food-frequency questionnaire: Folate and vitamin B12 examples. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verkleij-Hagoort, A.C.; de Vries, J.H.; Stegers, M.P.; Lindemans, J.; Ursem, N.T.; Steegers-Theunissen, R.P. Validation of the assessment of folate and vitamin B12 intake in women of reproductive age: The method of triads. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, M.D.; Walker, S.P.; Younger, N.M.; Bennett, F.I. Use of a food frequency questionnaire to assess diets of Jamaican adults: Validation and correlation with biomarkers. Nutr. J. 2011, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauvageot, N.; Alkerwi, A.; Albert, A.; Guillaume, M. Use of food frequency questionnaire to assess relationships between dietary habits and cardiovascular risk factors in NESCAV study: Validation with biomarkers. Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coathup, V.; Wheeler, S.; Smith, L. A method comparison of a food frequency questionnaire to measure folate, choline, betaine, vitamin C and carotenoids with 24-h dietary recalls in women of reproductive age. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, W.; Mitchell, P.; Reay, E.M.; Webb, K.; Harvey, P.W. Validity and reproducibility of a self-administered food frequency questionnaire in older people. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 1998, 22, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Health Organization (FAO/WHO). Preparation and Use of Food-Based Dietary Guidelines, Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Consultation Nicosia, Cyprus; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, A.J.; Noceti, E.M.; Block-Joy, A.; Block, T.; Block, G. Erythrocyte folate and its response to folic acid supplementation is assay dependent in women. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Owens, J.E.; Holstege, D.M.; Clifford, A.J. Comparison of two dietary folate intake instruments and their validation by RBC folate. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 3737–3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Rest, O.; Durga, J.; Verhoef, P.; Melse-Boonstra, A.; Brants, H.A. Validation of a food frequency questionnaire to assess folate intake of Dutch elderly people. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 98, 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, M.R.; Langdon, C.; Levy-Milne, R. Development of a validated food frequency questionnaire to determine folate intake. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2001, 62, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bacardí-Gascón, M.; Ley y de Góngora, S.; Castro-Vázquez, B.Y.; Jiménez-Cruz, A. Validation of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire to assess folate status. Results discriminate a high-risk group of women residing on the Mexico-US border. Arch. Med Res. 2003, 34, 325–330. [Google Scholar]

- Galván-Portillo, M.; Torres-Sánchez, L.; Hernández-Ramírez, R.U.; Anaya-Loyola, M.A. Validity and reproducibility of a food frequency questionnaire to estimate folate intake in a Mexican population. Salud Publica Mex. 2011, 53, 237–246. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara, J.; Yamamoto, S.; Iso, H.; Inoue, M.; Tsugane, S.; The JPHC FFQ Validation Study Group. Validity of a self-administered food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) and its generalizability to the estimation of dietary folate intake in Japan. Nutr. J. 2005, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirouzpanah, S.; Taleban, F.; Sabour, S.; Mehdipour, P.; Atri, M.; Farrin, N.; Houshyar-Rad, A.; Jalali-Farahani, S.; Khosroshahi, N.K. Validation of food frequency questionnaire to assess folate intake status in breast cancer patients. RJMS 2012, 18, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Pufulete, M.; Emery, P.W.; Nelson, M.; Sanders, T.A. Validation of a short food frequency questionnaire to assess folate intake. Br. J. Nutr. 2002, 87, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huybrechts, I.; De Backer, G.; De Bacquer, D.; Maes, L.; De Henauw, S. Relative Validity and Reproducibility of a Food-Frequency Questionnaire for Estimating Food Intakes among Flemish Preschoolers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2009, 6, 382–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Products | Serving Size | Frequency | Number of Servings * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fish and fish products | 50 g (deck of cards) | monthly | |

| Pasta, rice, groats | 100 g of cooked (2/3 of a glass) | monthly | |

| Bean, soybeans, peas | 100 g of cooked (2/3 of a glass) | monthly | |

| Nuts and seeds | 15 g (1 spoon) | monthly | |

| Grains, wheat bran and germs | 10 g (1 tablespoon) | monthly | |

| Milk, dairy beverages, cream | 250 g (1 glass) | weekly | |

| Rennet cheese | 20 g (thin slice) | weekly | |

| Cottage cheese, curd cheese, fromage frais, dairy desserts | 40 g (1 slice, large tablespoon) | weekly | |

| Egg | 50 g (1 egg) | weekly | |

| Egg yolk | 30 g (1 egg yolk) | weekly | |

| Liver | 100 g (palm of small hand) | weekly | |

| Other meat and offal | 100 g (palm of small hand) | weekly | |

| Pate | 40 g (1 tablespoon, 1 slice) | weekly | |

| Other cold cuts | 15 g (thin slice of ham, 3 slices of sausage, 1/3 of wiener) | weekly | |

| Bread | 35 g (1 medium slice, small roll) | weekly | |

| Oat, wheat, rye cereals, muesli | 10 g (1 tablespoon) | weekly | |

| Fluor added to dishes | 10 g (1 tablespoon) | weekly | |

| Corn flakes, corn crunches, puffed rice | 10 g (2 tablespoons) | weekly | |

| Potatoes | 70 g (1 medium, 3 tablespoons of puree) | weekly | |

| Broccoli, kale, Brussels sprouts, broad bean, asparagus, parsley, spinach | 100 g (half of a glass, 1 glass of leafy vegetables) | weekly | |

| Zucchini, chicory, corn, red pepper, cauliflower, leek, green cabbage, parsnip, green peas, green beans, lettuce, beetroot | 100 g (half of a glass, 1 glass of leafy vegetables) | weekly | |

| Celery, sorrel, cucumber, onion, eggplant, turnip, turnip cabbage, radish, pumpkin, carrot, tomato, red cabbage, green pepper | 100 g (half of a glass, 1 glass of leafy vegetables) | weekly | |

| Avocado | 70 g (half of medium one) | weekly | |

| Other fruits | 100 g (half of a glass) | weekly | |

| Chocolate | 20 g (3–4 chocolate bar squares) | weekly |

| Products | Serving Size | Folate Content/Serving (µg) |

|---|---|---|

| Fish and fish products | 50 g (deck of cards) | 5 |

| Pasta, rice, groats | 100 g of cooked (2/3 of a glass) | 12 |

| Bean, soybeans, peas | 100 g of cooked (2/3 of a glass) | 69 |

| Nuts and seeds | 15 g (1 spoon) | 9 |

| Grains, wheat bran and germs | 10 g (1 tablespoon) | 21 |

| Milk, dairy beverages, cream | 250 g (1 glass) | 11 |

| Rennet cheese | 20 g (thin slice) | 5 |

| Cottage cheese, curd cheese, fromage frais, dairy desserts | 40 g (1 slice, large tablespoon) | 8 |

| Egg | 50 g (1 egg) | 32 |

| Egg yolk | 30 g (1 egg yolk) | 30 |

| Liver | 100 g (palm of small hand) | 317 |

| Other meat and offal | 100 g (palm of small hand) | 10 |

| Pate | 40 g (1 tablespoon, 1 slice) | 14 |

| Other cold cuts | 15 g (thin slice of ham, 3 slices of sausage, 1/3 of wiener) | 1 |

| Bread | 35 g (1 medium slice, small roll) | 12 |

| Oat, wheat, rye cereals, muesli | 10 g (1 tablespoon) | 7 |

| Fluor added to dishes | 10 g (1 tablespoon) | 5 |

| Corn flakes, corn crunches, puffed rice | 10 g (2 tablespoons) | 1 |

| Potatoes | 70 g (1 medium, 3 tablespoons of puree) | 14 |

| Broccoli, kale, Brussels sprouts, broad bean, asparagus, parsley, spinach | 100 g (half of a glass, 1 glass of leafy vegetables) | 150 |

| Zucchini, chicory, corn, red pepper, cauliflower, leek, green cabbage, parsnip, green peas, green beans, lettuce, beetroot | 100 g (half of a glass, 1 glass of leafy vegetables) | 64 |

| Celery, sorrel, cucumber, onion, eggplant, turnip, turnip cabbage, radish, pumpkin, carrot, tomato, red cabbage, green pepper | 100 g (half of a glass, 1 glass of leafy vegetables) | 26 |

| Avocado | 70 g (half of medium one) | 43 |

| Other fruits | 100 g (half of a glass) | 15 |

| Chocolate | 20 g (3–4 chocolate bar squares) | 2 |

| 3-Day Dietary Record | Fol-IC-FFQ1 | Fol-IC-FFQ2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (µg) | 307 | 262 | 273 | ||

| Standard deviation (µg) | 119 | 132 | 136 | ||

| Median (µg) | 291 a,* | 226 b,* | 238 b,* | ||

| Minimum (µg) | 117 | 94 | 100 | ||

| Maximum (µg) | 845 | 903 | 869 | ||

| Share of individuals characterized in comparison with recommendation by Jarosz [39] | adequate intake | n | 27 | 15 | 19 |

| (%) | 36.0 | 20.0 | 25.3 | ||

| inadequate intake | n | 48 | 60 | 56 | |

| (%) | 64.0 | 80.0 | 74.7 | ||

| Fol-IC-FFQ1 vs. 3-Day Dietary Record | Fol-IC-FFQ1 vs. Fol-IC-FFQ2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Individuals classified into the same tertile | n | 30 | 56 |

| % | 40.0 | 74.7 | |

| Individuals misclassified (classified into opposite tertiles) | n | 9 | 3 |

| % | 12.0 | 4.0 | |

| Weighted κ statistic | 0.19 | 0.67 | |

| Individuals of the same folate intake adequacy category | n | 53 | 65 |

| % | 70.7 | 86.7 | |

| Individuals of the conflicting folate intake adequacy category | n | 22 | 10 |

| % | 29.3 | 13.3 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Głąbska, D.; Książek, A.; Guzek, D. Development and Validation of the Brief Folate-Specific Food Frequency Questionnaire for Young Women’s Diet Assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1574. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14121574

Głąbska D, Książek A, Guzek D. Development and Validation of the Brief Folate-Specific Food Frequency Questionnaire for Young Women’s Diet Assessment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017; 14(12):1574. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14121574

Chicago/Turabian StyleGłąbska, Dominika, Aneta Książek, and Dominika Guzek. 2017. "Development and Validation of the Brief Folate-Specific Food Frequency Questionnaire for Young Women’s Diet Assessment" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14, no. 12: 1574. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14121574

APA StyleGłąbska, D., Książek, A., & Guzek, D. (2017). Development and Validation of the Brief Folate-Specific Food Frequency Questionnaire for Young Women’s Diet Assessment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(12), 1574. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14121574