Impact of Point-of-Sale Tobacco Display Bans in Thailand: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Southeast Asia Survey

Abstract

:1. Introduction

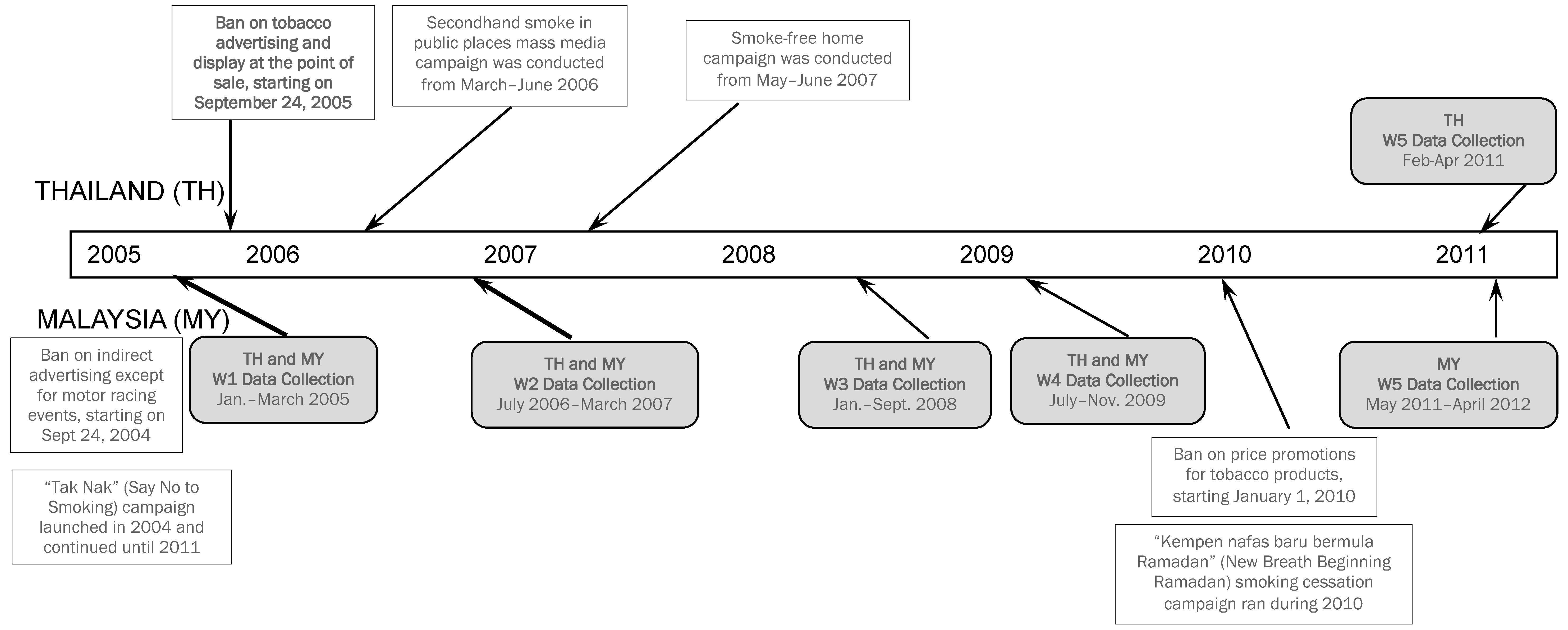

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sociodemographics and Smoking-Related Variables

2.2.2. Tobacco Advertising and Displays at Point-of-Sale

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Smoking-Related Characteristics

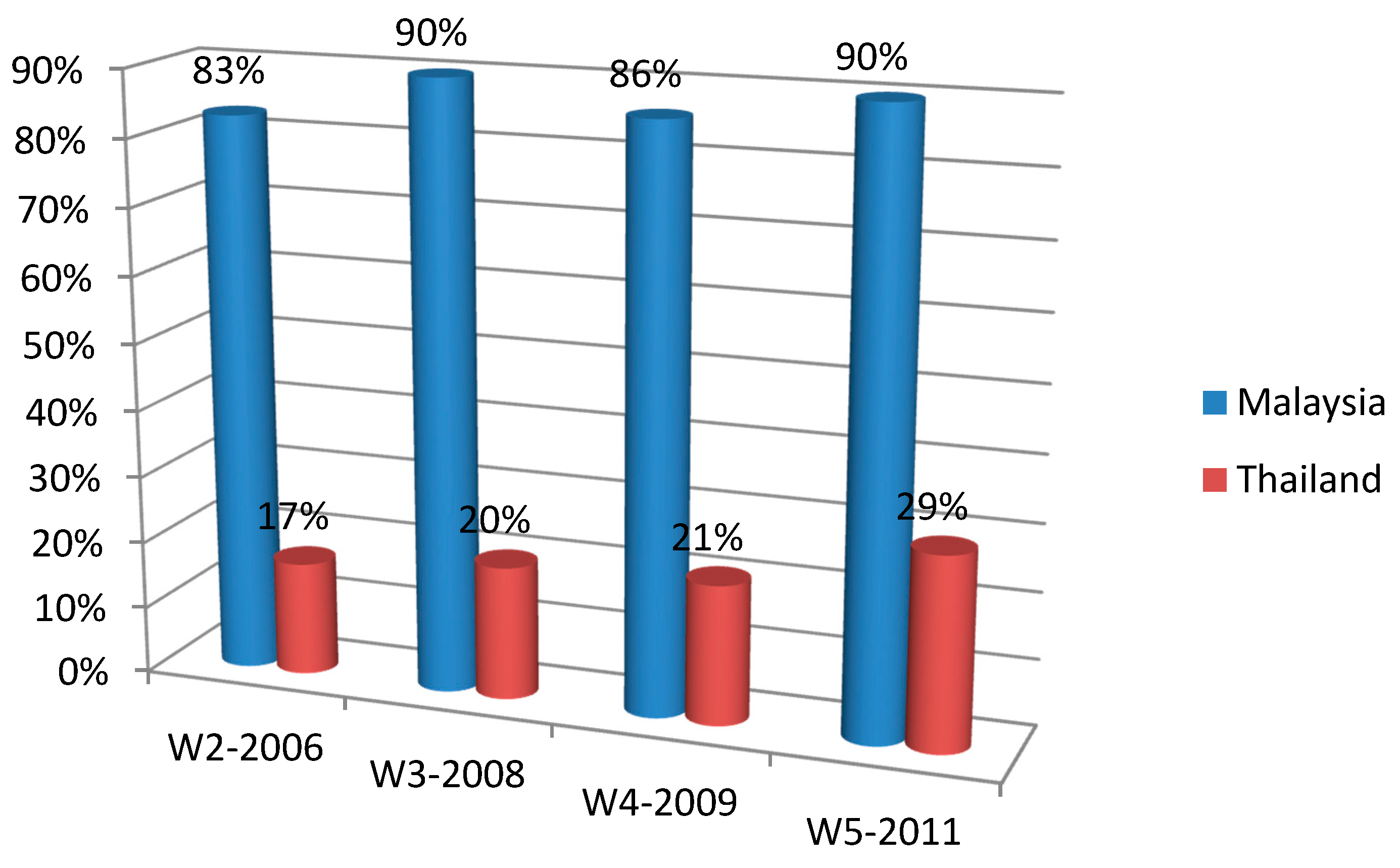

3.2. Noticing Cigarette Displays over Time

| Characteristics | Malaysia | Thailand | Total | Country Differences~ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of current smokers at each wave ^ | ||||

| Wave 1 (in early 2005) | 2004 | 2000 | 2004 | |

| Wave 2 (2006) | 1550 | 1866 | 3416 | |

| Wave 3 (2008) | 1846 | 2163 | 4009 | |

| Wave 4 (2009) | 1888 | 1907 | 3795 | |

| Wave 5 (2011) | 1773 | 1706 | 3479 | |

| Sex (% male, out of total unique individuals #: for Malaysia n = 4787; for Thailand n = 3584) | 97.3 | 91.2 | 94.7 | ** |

| Identified minority group (%) | 21.2 | 1.4 | 12.9 | *** |

| Urban/rural region (% urban) | 65.4 | 42.4 | 55.6 | *** |

| Age at recruitment (%) # | *** | |||

| 18–24 | 31.1 | 8.1 | 21.2 | *** |

| 25–39 | 32.9 | 26.1 | 29.9 | |

| 40–54 | 24.1 | 38.8 | 30.5 | |

| 55+ | 11.9 | 27.1 | 18.5 | |

| Education at recruitment (%) | *** | |||

| Low | 15.2 | 68.8 | 38.5 | |

| Moderate | 54.9 | 22.9 | 41.1 | |

| High | 29.8 | 8.3 | 20.5 | |

| Income at recruitment (%) | ||||

| Low | 28.1 | 25.7 | 26.1 | *** |

| Moderate | 34.2 | 30.9 | 32.8 | |

| High | 29.4 | 39.7 | 35.3 | |

| No information | 8.4 | 3.8 | 5.8 | |

| Cigarettes per day at recruitment (%) | *** | |||

| 1–10 | 48.3 | 54.7 | 51.1 | |

| 11–20 | 45.8 | 38.3 | 42.6 | |

| 21–30 | 3.5 | 4.6 | 4.0 | |

| 31+ | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.4 | |

| Intention to quit at recruitment (%) | *** | |||

| No intention/can’t say | 39.1 | 65.3 | 50.4 | |

| Beyond 6 months | 47.3 | 16.1 | 33.8 | |

| Within next 6 months | 8.2 | 12.4 | 10.0 | |

| Within next month | 5.4 | 6.2 | 5.8 | |

| Self-efficacy at recruitment (%) | *** | |||

| Not at all sure | 21.6 | 39.3 | 29.3 | |

| Somewhat sure/don’t know | 53.6 | 33.8 | 45.1 | |

| Very sure | 19.5 | 17.7 | 18.7 | |

| Extremely sure | 5.3 | 9.2 | 7.0 |

| Exposure | Malaysia | Thailand | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 n = 2004 ^ | W2 n = 1550 | W3 n = 1846 | W4 n = 1888 | W5 n = 1773 | W1 n = 2000 | W2 n = 1866 | W3 n = 2163 | W4 n = 1907 | W5 n = 1706 | |

| Noticed cigarette displays in shops (% yes) | N.A | 82.7 | 89.6 | 85.8 | 90.3 | N.A | 16.9 | 20.3 | 20.5 | 29.1 |

| Wave difference: OR ! | Ref. | 1.72 *** | 1.04 | 1.44 *** | Ref. | 1.22 ** | 1.21 ** | 1.80 *** | ||

| - Younger:older # | 86.6:79.4 *** | 93.3:85.9 *** | 87.1:83.6 | 92.9:81.4 *** | 21.1:15.2 ** | 24.6:18.3 ** | 23.9:18.9 * | 35.4:25.9 *** | ||

| - Urban:rural # | 85.9:77.8 *** | 91.8:86.2 *** | 85.9:86 | 91.1:88.8 | 18.3:16.2 | 18.6:21.1 | 19.8:21.1 | 31.9:26.6 * | ||

| - Malaysia only, f2f:phone ## | 83.1:82.1 | 86.1:92.6 *** | ||||||||

| - Thailand only, 1Bangkok:2other urban:3rural | 19.4:17.9:16.2 | 13.6:20.6:21.3 * | 21.4:19.1:21.0 | 37.2:28.7:26.6 ** | ||||||

| Noticed tob ads in stores (% yes) | 55.4 | 58.5 | 27.9 | 26.7 | 45.1 | 3.8 | 7.6 | 2.7 | 10.8 | 9.2 |

| Wave difference: OR | Ref. | 1.06 | 0.30 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.62 *** | Ref. | 2.09 *** | 0.77 | 3.22 *** | 2.48 *** |

| - Younger:older | 59.2:51.7 ** | 59.4:57.2 | 24.1:31.5 ** | 26.1:28 | 47.1:39.3 ** | 4.1:3.6 | 7.8:7.6 | 3.1:2.6 | 11.7:10.4 | 9.8:8.9 |

| - Urban:rural | 51:62.6 *** | 58:59.3 | 22.2:36.9 *** | 25.3:28.9 | 43.4:47.9 | 4.6:3.5 | 6.3:8.3 * | 1.4:3.4 ** | 8.9:12.4 * | 8.6:9.7 |

| - Malaysia only, f2f *:Phone | 59.9:55.8 | 47.9:11.3 *** | ||||||||

| - Thailand only, 1Bangkok:2other urban:3rural | 7.2:3.3:3.4 * | 6.4:6.3:8.3 | 0:2.1:3.4 * | 7.4:9.6:12.4 * | 10.2:7.7:9.7 | |||||

| Noticed tob ads around street vendors (% yes) | 47.2 | 43.6 | 23.2 | 16.4 | 29.1 | 7.1 | 9.6 | 4.2 | 7.8 | 10.4 |

| Wave difference: OR | Ref. | 0.83 ** | 0.34 *** | 0.22 *** | 0.47 *** | Ref. | 1.40 ** | 0.67 ** | 1.24 | 1.58 *** |

| - Younger:older | 51.2:43.3 ** | 42.7:43.6 | 19.7:26.8 *** | 15.7:18.2 | 29.4:28.1 | 4.9:8 * | 7.4:10.6 * | 2.7:4.8 * | 6.6:8.4 | 10.3:10.4 |

| - Urban:rural | 44.8:51.2 ** | 44.2:42.7 | 20.5:27.6 * | 15.7:17.5 | 28.5:30.1 | 2.3:9.1 *** | 5.1:12.1 *** | 1.2:5.7 *** | 5.4:9.8 *** | 8.8:11.8 * |

| - Malaysia only, f2f:phone | 42.9:44.9 | 34.9:13.5 *** | ||||||||

| - Thailand only, 1Bangkok:2other urban:3rural | 1.4:2.8:9.1 *** | 4.3:5.4:12.1 *** | 0:1.7:5.7 *** | 5.2:5.4:9.8 ** | 12.3:6.7:11.8 ** | |||||

3.3. Noticing Tobacco Advertising at POS over Time

3.4. Additional Results on POS Tobacco Display Bans (2006 Survey Only)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paynter, J.; Edwards, R.; Schluter, P.; McDuff, I. Point of sale tobacco displays and smoking among 14- 15 years olds in New Zealand: A cross-sectional study. Tob. Control 2009, 18, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. Tobacco control monograph No.19. In The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco Use; Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2008; pp. 211–281. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2013: Enforcing Bans on Tobacco Advertising, Promotion and Sponsorship; World Health Organization: Geneva, Swizterland, 2013.

- Carter, O.B.J.; Mills, B.W.; Donovan, R.J. The effect of retail cigarette pack displays on unplanned purchases: Results from immediate post-purchase interviews. Tob. Control 2009, 18, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakefield, M.; Germain, D.; Durkin, S.; Henriksen, L. An experimental study of effects on schoolchildren of exposure to point-of-sale cigarette advertising and pack displays. Health Educ. Res. 2006, 21, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriksen, L.; Feighery, E.C.; Schleicher, N.C.; Haladjian, H.H.; Fortmann, S.P. Reaching youth at the point of sale: Cigarette marketing is more prevalent in stores where adolescents shop frequently. Tob. Control 2004, 13, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakefield, M.; Germain, D.; Henriksen, L. The effect of retail cigarette pack displays on impulse purchase. Addiciton 2008, 103, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriksen, L.; Flora, J.A.; Feighery, E.; Fortmann, S.P. Effects on youth of exposure to retail tobacco advertising. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 1771–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovato, C.; Linn, G.; Stead, L.F.; Best, A. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paynter, J.; Edwards, R. The impact of tobacco promotion at the point of sale: A systematic review. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2009, 11, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germain, D.; McCarthy, M.; Wakefield, M. Smoker sensitivity to retail tobacco displays and quitting: A cohort study. Addiciton 2009, 105, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Borland, R.; Fong, G.T.; Thrasher, J.F.; Hammond, D.; Cummings, K.M. Impact of point-of-sale tobacco display bans: Findings from the international tobacco control four country survey. Health Educ. Res. 2013, 28, 898–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeill, A.; Lewis, S.; Quinn, C.; Mulcahy, M.; Clancy, L.; Hastings, G.; Edwards, R. Evaluation of the removal of point-of-sale tobacco displays in Ireland. Tob. Control 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Public Health and Tobacco Policy. Tobacco Product Display Restrictions. Available online: http://publichealthlawcenter.org/sites/default/files/nycenter-syn-tobproductdisplaybans-2013.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2013).

- Health Canada. Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey. Available online: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/tobactabac/research-recherche/stat/ctums-esutc_2011-eng.php. (accessed on 29 August 2012).

- Statistics Iceland. How Many Icelanders Smoke? Available onlne: http://www.statice.is/Pages/2004 (accessed on 15 February 2013).

- WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008. The MPOWER Package; World Health Organization: Geneva, Swizterland, 2008.

- Fathelrahman, A.I.; Li, L.; Borland, R.; Yong, H.H.; Omar, M.; Awang, R.; Sirirassamee, B.; Fong, G.T.; Hammond, D. Stronger pack warnings predict quitting more than weakers ones: Finding from the ITC Malaysia and Thailand surveys. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2013, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitanondh, H. Thailand Country Report on Tobacco Advertising and Promotion Bans. Posted at the eScholarship Repository, University of California. Available online: http://repositories.cdlib.org/tc/whotcp/ThaiCR2003/ (accessed on 7 May 2008).

- Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance (SEATCA). Fatal Attraction: The Story of Point-of-Sale in the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam. Available online: http://resources.seatca.org/Fatal%20Attraction.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2014).

- Yong, H.H.; Borland, R.; Hammond, D.; Sirirassamee, B.; Ritthiphakdee, B.; Awang, R.; Omar, M.; Kin, F.; Zain, Z.B.; Lee, W.B.; et al. Levels and correlates of awareness of tobacco promotional activities among adult smokers in Malaysia and Thailand: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Southeast Asia (ITC-SEA) Survey. Tob. Control 2008, 17, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Yong, H.H.; Borland, R.; Fong, G.T.; Thompson, M.E.; Jiang, Y.; Sirirassamee, B.; Hastings, G.; Harris, F. Reported awareness of tobacco advertising and promotion in China compared to Thailand, Australia and the USA. Tob. Control 2009, 18, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ITC Project. ITC Malaysia National Report. Findings from Wave 1 to 4 Surveys (2005–2009); University of Waterloo: Waterloo, Ontario, Canada; Universiti Sains Malaysia: Pulau Pinang, Malaysia; Ministry of Health: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- ITC Project. ITC SEA Wave 1 (2005) Technical Report. Available online: http://www.itcproject.org/countries/thailand (accessed on 21 March 2014).

- ITC Project. ITC SEA Wave 5 (2011–2012) Technical Report. Available online: http://www.itcproject.org/countries/thailand (accessed on 21 March 2014).

- Ross, H.; Driezen, P.; Sirirassamee, B.; Kin, F. Cigarette purchasing behaviour in Thailand and Malaysia: Comparative analysis of a semi-monopolistic and a free-market structure. Glob. Public Health 2009, 4, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Li, L.; Yong, H.H.; Borland, R.; Wu, X.; Li, Q.; Wu, C.; Foong, K. Regional differences in awareness of tobacco advertising and promotion in China: findings from the ITC China Survey. Tob. Control 2010, 19, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.; Planinac, L.; Lavack, A.; Robinson, D.; O’Connor, S.; di Nardo, J. Changes in retail tobacco promotions in a cohort of stores before, during, and after a tobacco product display ban. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 1879–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phetphum, C.; Noosorn, N.; Nimpitakphong, P.; Mekrungrongwong, S. A Community of Practices (COPs) Approach for Rural Retailer Behavioral Change Concerning Tobacco Sale to Minors. Doctoral Thesis, Faculty Public Health, Naresuan University, Phitsanuloke, Thailand, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.C.; Thompson, M.E.; Boudreau, C.; Fong, G.T. Accounting for the effects of data collection modes in population surveys. In Proceedings of the Statistics Canada Symposium 2010, Social Statistics: The Interplay among Censuses, Surveys and Administrative Data, Ottawa, AB, Canada, 26–29 October 2010.

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, L.; Borland, R.; Yong, H.-H.; Sirirassamee, B.; Hamann, S.; Omar, M.; Quah, A.C.K. Impact of Point-of-Sale Tobacco Display Bans in Thailand: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Southeast Asia Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 9508-9522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120809508

Li L, Borland R, Yong H-H, Sirirassamee B, Hamann S, Omar M, Quah ACK. Impact of Point-of-Sale Tobacco Display Bans in Thailand: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Southeast Asia Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015; 12(8):9508-9522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120809508

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Lin, Ron Borland, Hua-Hie Yong, Buppha Sirirassamee, Stephen Hamann, Maizurah Omar, and Anne C.K. Quah. 2015. "Impact of Point-of-Sale Tobacco Display Bans in Thailand: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Southeast Asia Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12, no. 8: 9508-9522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120809508

APA StyleLi, L., Borland, R., Yong, H.-H., Sirirassamee, B., Hamann, S., Omar, M., & Quah, A. C. K. (2015). Impact of Point-of-Sale Tobacco Display Bans in Thailand: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Southeast Asia Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(8), 9508-9522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120809508