The Influence of Nutritional Factors on Verbal Deficits and Psychopathic Personality Traits: Evidence of the Moderating Role of the MAOA Genotype

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Poor Nutrition, Verbal Deficits, and Psychopathic Personality Traits

1.2. MAOA Genotype, Verbal Deficits, and Psychopathic Personality Traits

1.3. Are The Effects of Poor Nutrition on Verbal Deficits and Psychopathic Traits Conditional?

1.4. The Current Study

2. Method

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Outcome Measures

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal Deficits | 51.26 | 28.58 | 0–100 |

| Psychopathic Traits (Wave 4) | 0.00 | 0.44 | −1.40–1.52 |

| Meal Deprivation | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0–1 |

| Low Vegetable Consumption | 1.02 | 0.78 | 0–2 |

| High Fast Food Consumption | 2.43 | 1.83 | 0–7 |

| MAOA (Low Activity) | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0–1 |

| Age Wave 1 | 16.11 | 1.68 | 12.12–20.86 |

| Race (Non-White = 1) | 0.34 | 0.48 | 0–1 |

| Low SES | 0.22 | 0.41 | 0–1 |

| Low Self-Control (Wave 1) | 0.00 | 0.65 | −1.50–2.93 |

| Family Meals | 4.70 | 2.44 | 0–7 |

| TV Viewing (Hrs per Week) | 17.13 | 15.76 | 0–80 |

| Video Games (Hrs per Week) | 4.52 | 8.15 | 0–60 |

| Neighborhood Disadvantage | 0.00 | 0.61 | −0.73–2.35 |

| Low Maternal Attachment | 0.00 | 0.87 | −0.41–7.38 |

| Maternal Disengagement | 0.00 | 0.74 | −0.95–3.97 |

| Low Maternal Involvement | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0–1 |

| Low Maternal Supervision | 0.46 | 0.66 | 0–3 |

2.2.2. Nutrition and Genetic Measures

2.3. Adolescent Traits

2.4. Family Socialization, Home Environment and Neighborhood Measures

2.5. Controls

2.6. Plan of Analysis

3. Results

| Covariates | Verbal Deficits | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 b/β | Model 2 b/β | Model 3 b/β | Model 4 b/β | |

| Meal Deprivation | 1.85 *, 0.06 (0.87) | 1.87 *, 0.06 (0.87) | 1.84 *, 0.06 (0.87) | 1.90 *, 0.07 (0.88) |

| Low Vegetable Consumption | 4.64 *, 0.16 (0.87) | 4.64 *, 0.16 (0.87) | 4.64 *, 0.16 (0.86) | 4.65 *, 0.16 (0.87) |

| High Fast Food Consumption | 0.71, 0.02 (0.86) | 0.72, 0.02 (0.87) | 0.72, 0.02 (0.86) | 0.79, 0.03 (0.86) |

| MAOA | −0.98, −0.03 (0.83) | −0.97, −0.03 (0.82) | −0.97, −0.03 (0.82) | −0.97, −0.03 (0.82) |

| Age | −0.97, −0.06 (0.55) | −0.97, −0.05 (0.56) | −0.93, −0.05 (0.56) | −0.99, −0.06 (0.55) |

| Race (non-white) | 15.27 *, 0.25 (1.90) | 15.34 *, 0.25 (1.90) | 15.34 *, 0.25 (1.89) | 15.41 *, 0.25 (1.89) |

| Low SES | 14.53 *, 0.20 (2.18) | 14.44 *, 0.20 (2.18) | 14.60 *, 0.20 (2.16) | 14.24 *, 0.20 (2.18) |

| Low Self-Control(Wave 1) | 2.97 *, 0.07 (1.36) | 2.92 *, 0.07 (1.35) | 3.22 *, 0.07 (1.36) | 2.84 *, 0.06 (1.34) |

| Family Meals | −0.50, −0.04 (0.36) | −0.52, −0.04 (0.36) | −0.49, −0.04 (0.36) | −0.51, −0.04 (0.36) |

| TV Viewing | 0.11, 0.06 (0.06) | 0.11, 0.06 (0.06) | 0.10, 0.05 (0.06) | 0.11, 0.06 (0.06) |

| Video Games | 0.15, 0.04 (0.10) | 0.15, 0.04 (0.10) | 0.16, 0.04 (0.10) | 0.16, 0.04 (0.10) |

| Neighborhood Disadvantage | −1.55, −0.03 (1.43) | −1.60, −0.03 (1.43) | −1.51, −0.03 (1.43) | −1.52, −0.03 (1.43) |

| Low Maternal Attachment | −2.29, −0.06 (1.33) | −2.27, −0.06 (1.33) | −2.18, −0.06 (1.30) | −2.23, −0.06 (1.31) |

| Maternal Disengagement | −1.56, −0.04 (1.34) | −1.53, −0.04 (1.34) | −1.53, −0.04 (1.33) | −1.38, −0.03 (1.35) |

| Low Maternal Involvement | 4.27, 0.02 (8.96) | 3.86, 0.02 (8.96) | 4.00, 0.02 (8.79) | 3.99, 0.02 (8.75) |

| Low Maternal Supervision | −0.06, 0.00 (1.31) | −0.14, 0.00 (1.31) | −0.16, 0.00 (1.31) | 0.06, 0.00 (1.32) |

| Meal Deprivation X MAOA | NA | 0.79, 0.03 (0.82) | NA | NA |

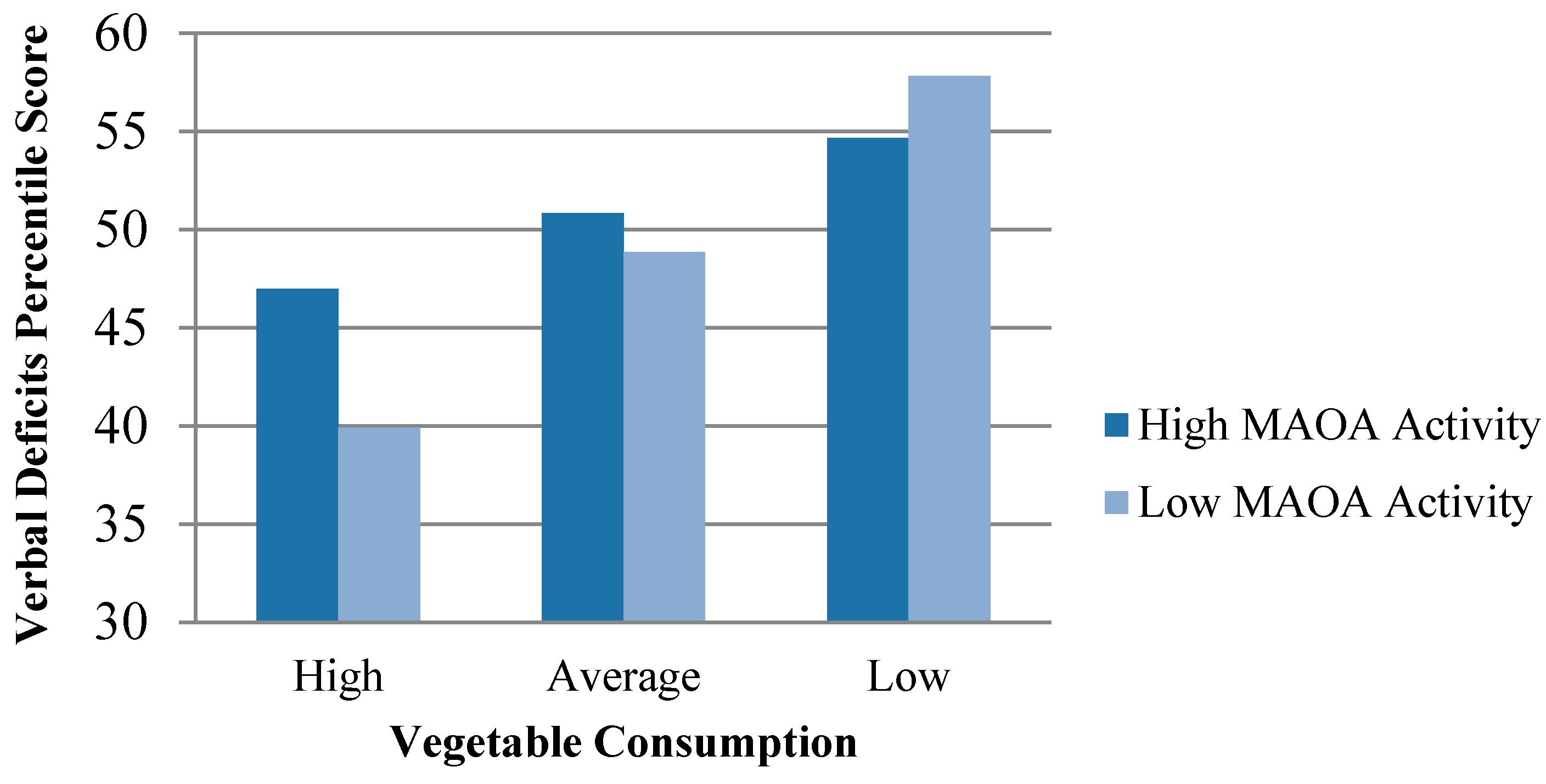

| Low Vegetable Consumption MAOA | NA | NA | 2.21 *, 0.08 (0.84) | NA |

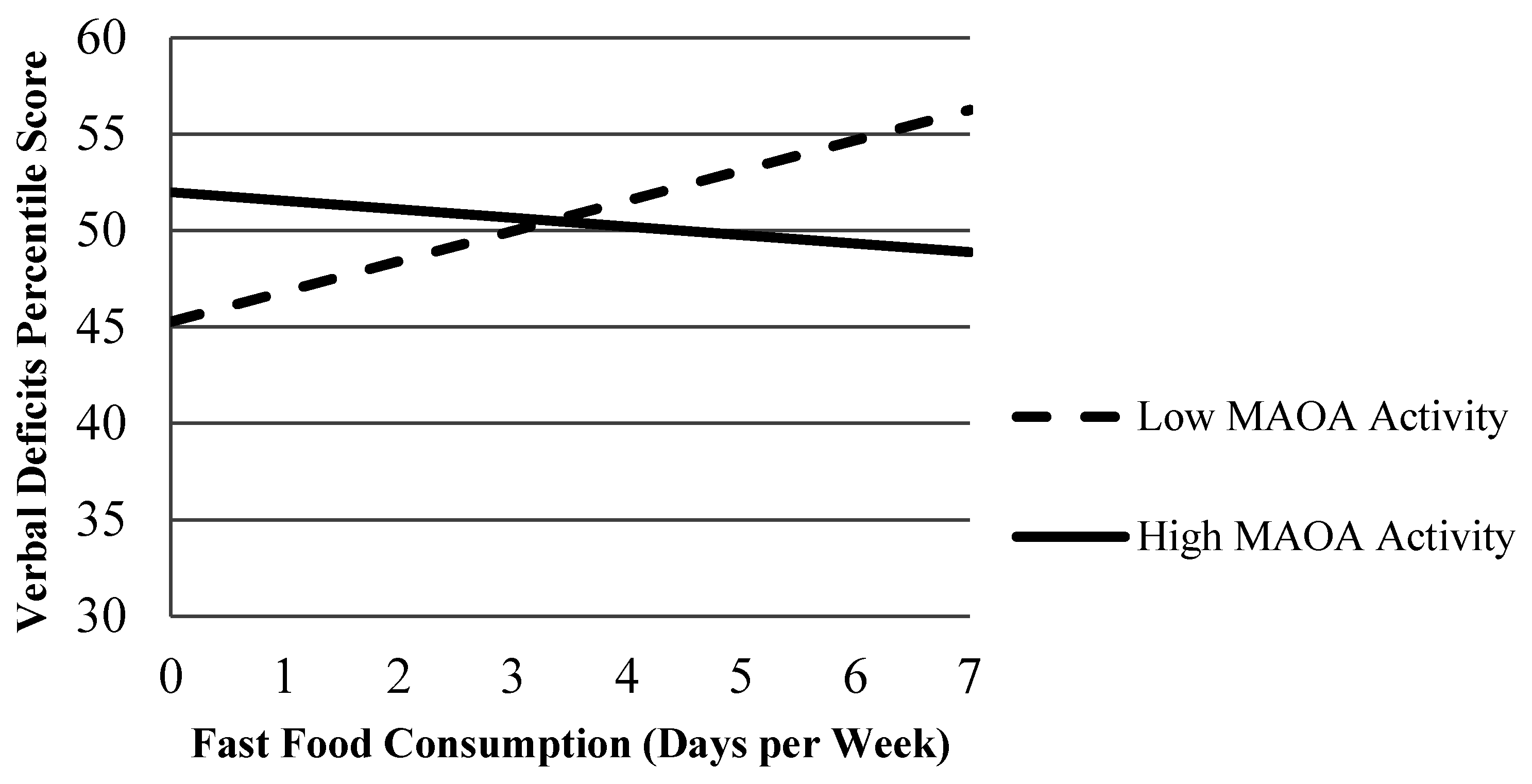

| High Fast Food Consumption X MAOA | NA | NA | NA | 1.93 *, 0.07 0.85 |

| N | 1030 | 1030 | 1030 | 1030 |

| R2 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| Covariates | Psychopathic Personality Traits | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 b/β | Model 2 b/β | Model 3 b/β | Model 4 b/β | |

| Meal Deprivation | 0.07 *, 0.17 (0.02) | 0.07 *, 0.17 (0.02) | 0.07 *, 0.17 (0.02) | 0.08 *, 0.18 (0.02) |

| Low Vegetable Consumption | 0.01, 0.02 (0.02) | 0.01, 0.02 (0.02) | 0.01, 0.02 (0.02) | 0.01, 0.02 (0.02) |

| High Fast Food Consumption | 0.02, 0.04 (0.02) | 0.02, 0.04 (0.02) | 0.02, 0.04 (0.02) | 0.02, 0.04 (0.01) |

| MAOA | 0.02, 0.04 (0.01) | 0.02, 0.04 (0.01) | 0.02, 0.04 (0.01) | 0.02, 0.05 (0.01) |

| Age | −0.01, −0.03 (0.01) | −0.01, −0.03 (0.01) | −0.01, −0.03 (0.01) | −0.01, −0.03 (0.01) |

| Race (non-white) | 0.02, 0.03 (0.02) | 0.02, 0.03 (0.02) | 0.02, 0.03 (0.02) | 0.03, 0.03 (0.03) |

| Low SES | 0.11 *, 0.10 (0.04) | 0.11 *, 0.10 (0.04) | 0.11 *, 0.10 (0.04) | 0.10 *, 0.09 (0.04) |

| Low Self-Control(Wave 1) | 0.10 *, 0.15 (0.02) | 0.10 *, 0.15 (0.02) | 0.10 *, 0.15 (0.02) | 0.10 *, 0.14 (0.02) |

| Family Meals | 0.00, 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00, 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00, 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00, 0.00 (0.01) |

| TV Viewing | 2.4 × 10−3 *, 0.08 (1.1 × 10−3) | 2.4 × 10−3 *, 0.08 (1.1 × 10−3) | 2.4 × 10−3 *, 0.08 (1.1 × 10−3) | 2.4 × 10−3 *, 0.08 (1.1 × 10−3) |

| Video Games | 1.6 × 10−3, −0.03 (2.4 × 10−3) | −1.7 × 10−3, −0.03 (2.5 × 10−3) | −1.6 × 10−3, −0.03 (2.4 × 10−3) | −1.5 × 10−3, −0.03 (2.4 × 10−3) |

| Neighborhood Disadvantage | 0.03, 0.05 (0.03) | 0.03, 0.05 (0.03) | 0.03, 0.05 (0.03) | 0.04, 0.07 (0.02) |

| Low Maternal Attachment | 0.03, 0.06 (0.02) | 0.03, 0.06 (0.02) | 0.03, 0.06 (0.02) | 0.04, 0.07 (0.02) |

| Maternal Disengagement | 0.04, 0.07 (0.02) | 0.04, 0.07 (0.03) | 0.04, 0.07 (0.03) | 0.05 *, 0.08 (0.02) |

| Low Maternal Involvement | 0.08, 0.02 (0.16) | 0.07, 0.02 (0.16) | 0.08, 0.02 (0.16) | 0.08, 0.02 (0.16) |

| Low Maternal Supervision | −0.04 *, −0.06 (0.02) | −0.04 *, −0.07 (0.02) | −0.04 *, −0.06 (0.02) | −0.04 *, −2 |

| Meal Deprivation X MAOA | NA | 0.02, 0.04 (0.01) | NA | NA |

| Low Vegetable Consumption X MAOA | NA | NA | 0.00, 0.01 (0.01) | NA |

| High Fast Food Consumption X MAOA | NA | NA | NA | 0.07 *, 0.16 (0.01) |

| N | 919 | 919 | 919 | 919 |

| R2 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.15 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gorgeiff, M. Nutrition and the developing brain: nutrient priorities and measurement. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 614S–620S. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Pinilla, F. Brain foods: The effects of nutrients on brain function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, B.; Rao, S.; Chandramouli, B. Cognitive development in children with chronic protein energy malnutrition. Behav. Brain Funct. 2008, 4, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukowski, A.; Koss, M.; Burden, M.; Jonides, J.; Nelson, C.; Kaciroti, N.; Jimenez, E.; Lozoff, B. Iron deficiency in infancy and neurocognitive functioning at 19 years: Evidence of long-term deficits in executive function and recognition memory. Nutr. Neurosci. 2010, 13, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Raine, A.; Venables, P.; Dalais, C.; Mednick, S. Malnutrition at age 3 years and lower cognitive ability at age 11 years. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2003, 157, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, C.; Martyn, C.; Marriott, L.; Limond, J.; Crozier, S.; Inskip, H.; Godfrey, K.; Law, C.; Cooper, C.; Robinson, S. Dietary patterns in infancy and cognitive and neuropsychological function in childhood. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2009, 50, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waber, D.; Bryce, C.; Fitzmaurice, G.; Zichlin, M.; McGaughy, J.; Girard, J.; Galler, J. Neuropsychological outcomes at midlife following moderate to severe malnutrition in infancy. Neuropsychology 2014, 28, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galler, J.; Bryce, C.; Zichlin, M.; Fitzmaurice, G.; Eaglesfield, G.; Waber, D. Infant malnutrition is associated with persisting attention deficits in middle adulthood. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggs, N.; Spruijt-Metz, D.; Sakuma, K.; Chou, C.; Pentz, M. Executive cognitive function and food intake in children. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2010, 42, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, A.; Ying, Z.; Gomez-Pinilla, F. Dietary omega-3 fatty acids normalize BDNF levels, reduce oxidative damage, and counteract learning disability after traumatic brain injury in rats. J. Neurotrauma 2004, 21, 1457–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinn, N. Nutritional and dietary influences on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Nutr. Rev. 2008, 66, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galler, J.; Bryce, C.; Waber, D.; Medford, G.; Eaglesfield, G.; Fitzmaurice, G. Early malnutrition predicts parent reports of externalizing behaviors at ages 9–17. Nutr. Neurosci. 2011, 14, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Raine, A.; Venables, P.; Mednick, S. Malnutrition at age 3 years and externalizing behavior problems at ages 8, 11, and 17 years. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 2005–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oddy, W.; Robinson, M.; Ambrosini, G.; de Klerk, N.; Beilin, L.; Silburn, S.; Stanley, F. The association between dietary patterns and mental health in early adolescence. Prev. Med. 2009, 49, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Raine, A. Prefrontal structural and functional brain imaging findings in antisocial, violent, and psychopathic individuals: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2009, 174, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabia, S.; Nabi, H.; Kivimaki, M.; Shipley, M.; Marmot, M.; Singh-Manoux, A. Health behaviors from early to late midlife as predictors of cognitive function: The Whitehall II Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 170, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, X.; Scott, T.; Gao, X.; Maras, J.; Bakun, P.; Tucker, K. Mediterranean diet, Healthy Eating Index 2005, and cognitive function in middle-aged and older Puerto Rican adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corley, J.; Starr, J.; McNeill, G.; Deary, I. Do dietary patterns influence cognitive function in old age? Int. Psychogeriatry 2013, 25, 1393–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, D.; Beaver, K. The role of adolescent nutrition and physical activity in the prediction of verbal intelligence during early adulthood: A genetically informed analysis of twin pairs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gesch, C.; Hammond, S.; Hampson, S.; Eves, A.; Crowder, M. Influence of supplementary vitamins, minerals and essential fatty acids on the antisocial behaviour of young adult prisoners: Randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2002, 181, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, D.; Veasey, R.; Watson, A.; Dodd, F.; Jones, E.; Maggini, S.; Haskell, C. Effects of high-dose B vitamin complex with vitamin C and minerals on subjective mood and performance in healthy males. Psychopharmacology 2010, 211, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaalberg, A.; Nijman, H.; Bulten, E.; Stroosma, L.; van der Staak, C. Effects of nutritional supplements on aggression, rule-breaking, and psychopathology among young adult prisoners. Aggr. Behav. 2010, 36, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Zandi, P.; Tucker, K.; Fitzpatrick, A.; Kuller, L.; Fried, L.; Burke, G.; Carlson, M. Benefits of fatty fish on dementia risk are stronger for those without APOE ε4. Neurology 2005, 65, 1409–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petot, G.; Traore, F.; Debanne, S.; Lerner, A.; Smyth, K.; Friedland, R. Interactions of apolipoprotein E genotype and dietary fat intake of healthy older persons during mid-adult life. Metabolism 2003, 52, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simopoulos, A. Omega-3 fatty acids in inflammation and autoimmune diseases. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2002, 21, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaver, K.; Vaughn, M.; DeLisi, M.; Barnes, J.; Boutwell, B. The neuropsychological underpinnings to psychopathic personality traits in a nationally representative and longitudinal sample. Psychiatry Q 2012, 83, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLisi, M.; Vaughn, M.; Beaver, K.; Wright, J. The Hannibal Lecter myth: Psychopathy and verbal intelligence in the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment study. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2010, 32, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaver, K.; DeLisi, M.; Vaughn, M.; Barnes, J. Monoamine oxidase A genotype is associated with gang membership and weapon use. Compr. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspi, A.; McClay, J.; Moffitt, T.; Mill, J.; Martin, J.; Craig, I.; Poulton, R. Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science 2002, 297, 851–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Hwang, W.; Dickerman, B.; Compher, C. Regular breakfast consumption is associated with increased IQ in kindergarten children. Early Hum. Dev. 2013, 89, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dangour, A.; Allen, E.; Elbourne, D.; Fletcher, A.; Richards, M.; Uauy, R. Fish consumption and cognitive function among older people in the UK: Baseline data from the OPAL study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2009, 13, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryan, J.; Calvaresi, E.; Hughes, D. Short-term folate, vitamin B-12 or vitamin B-6 supplementation slightly affects memory performance but not mood in women of various ages. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar]

- Nyaradi, A.; Li, J.; Hickling, S.; Whitehouse, A.; Foster, J.; Oddy, W. Diet in the early years of life influences cognitive outcomes at 10 years: A prospective cohort study. Acta. Paediatr. 2013, 102, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gow, R.; Vallee-Tourangeau, F.; Crawford, M.; Taylor, E.; Ghebremeskel, K.; Bueno, A.; Hibbeln, J.; Sumich, A.; Rubia, K. Omega-3 fatty acids are inversely related to callous and unemotional traits in adolescent boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2013, 88, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peet, M. International variations in the outcome of schizophrenia and the prevalence of depression in relation to national dietary practices: An ecological analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2004, 184, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raine, A.; Mellingen, K.; Liu, J.; Venables, P.; Mednick, S. Effects of environmental enrichment at ages 3–5 years on schizotypal personality and antisocial behavior at ages 17 and 23 years. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 1627–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasinska, A.; Yasuda, M.; Burant, C.; Gregor, N.; Khatri, S.; Sweet, M.; Falk, E. Impulsivity and inhibitory control deficits are associated with unhealthy eating in young adults. Appetite 2012, 59, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hare, R. Psychopathy as a risk factor for violence. Psychiatric Q. 1999, 70, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenthaler, S.; Bier, I. The effect of vitamin-mineral supplementation on juvenile delinquincy among American schoolchildren: A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2000, 6, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinath, F.; Price, T.; Dale, P.; Plomin, R. The genetic and environmental origins of language disability and ability. Child Dev. 2004, 75, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, Q.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Guan, L.; Chen, Y.; Ji, N.; Liu, L.; Faraone, S. Gene-gene interaction between COMT and MAOA: Potentially predicts the intelligence of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder boys in China. Behav. Genet. 2010, 40, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, L.; Gatt, J.; Kuan, S.; Dobson-Stone, C.; Palmer, D.; Paul, R.; Song, L.; Costa, P.; Schofield, P.; Gordon, E. A Polymorphism of the MAOA gene is associated with emotional brain markers and personality traits on an antisocial index. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009, 34, 1797–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, I.; Liu, X.; Schutz, C.; White, B.; Jenkins, E.; Brown, W.; Holden, J. Association of autism severity with a monoamine oxidase A functional polymorphism. Clin. Genet. 2003, 64, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, I.; Liu, X.; Lewis, M.; Chudley, A.; Forster-Gibson, C.; Gonzalez, M.; Jenkins, E.; Brown, W.; Holden, J. Autism severity is associated with child and maternal MAOA genotypes. Clin. Genet. 2011, 79, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.; Won, S.; Nam, M.; Chung, J.; Kwack, K. Interaction between MAOA and FOXP2 in association with autism and verbal communication in a Korean population. J. Child Neurol. 2014, 29, NP207–NP211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, T.; Langley, K.; Rice, F.; van den Bree, M.; Ross, K.; Wilkinson, L.; Owen, M.; O’Donovan, M.; Thapar, A. Psychopathy trait scores in adolescents with childhood ADHD: The contribution of genotypes affecting MAOA, 5HTT and COMT activity. Psychiatr. Genet. 2009, 19, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Guan, L.; Chen, Y.; Ji, N.; Li, H.; Li, Z.; Qian, Q.; Yang, L.; Glatt, S.; Faraone, S.; Wang, Y. Association analyses of MAOA in Chinese Han subjects with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Family-based association test, case-control study, and quantitative traits of impulsivity. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2011, 156, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Dai, Q.; Ekperi, L.; Dehal, A.; Zhang, J. Fish consumption and severely depressed mood, findings from the first national nutrition follow-up study. Psychiatry Res. 2011, 190, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbs-Tait, L.; Mulugeta, A.; Bogale, A.; Kennedy, T.; Baker, E.; Stoecker, B. Main and interaction effects of iron, zinc, lead, and parenting on children’s cognitive outcomes. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2009, 34, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, M.; McCloskey, M.; Fanning, J.; Schumacher, J.; Coccaro, E. Serotonin augmentation reduces response to attack in aggressive individuals. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 20, 714–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haberstick, B.; Smolen, A.; Hewitt, J. Family-Based Association Test of the 5HTTLPR and aggressive behavior in a general population sample of children. Biol. Psychiatry 2006, 59, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golub, M.; Hogrefe, C. Prenatal iron deficiency and monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) polymorphisms: Combined risk for later cognitive performance in rhesus monkeys. Genes Nutr. 2014, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, J.; Breen, G.; Quinn, J.; Tibu, F.; Sharp, H.; Pickles, A. Evidence for interplay between genes and maternal stress in utero: Monoamine oxidase A polymorphism moderates effects of life events during pregnancy on infant negative emotionality at 5 weeks. Genes Brain Behav. 2013, 12, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haberstick, B.; Lessem, J.; Hopfer, C.; Smolen, A.; Ehringer, M.; Timberlake, D.; Hewitt, J. Monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) and antisocial behaviors in the presence of childhood and adolescent maltreatment. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2005, 135, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaver, K.; DeLisi, M.; Vaughn, M.; Wright, J. The intersection of genes and neuropsychological deficits in the prediction of adolescent delinquency and low self-control. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2010, 54, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Amato, R.; Gray, J.; Dean, R. Construct validity of the PPVT with neuropsychological, intellectual, and achievement measures. J. Clin. Psychology 1988, 44, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quattrocchi, M.; Golden, C. Peabody picture vocabulary test-revised and luria-nebraska neuropsychological battery for children: Inter-correlations for normal youngsters. Percept. Mot. Skills 1983, 56, 632–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaver, K.; Rowland, M.; Schwartz, J.; Nedelec, J. The genetic origins of psychopathic personality traits in adult males and females: Results from an adoption-based study. J. Crim. Justice 2011, 39, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaimo, K.; Olson, C.M.; Frongillo, E.A., Jr.; Briefel, R.R. Food insufficiency, family income, and health in US preschool and school-aged children. Am. J. Public Health 2001, 91, 781–786. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stewart, S.; Menning, C. Family structure, nonresident father involvement, and adolescent eating patterns. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 45, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahra, J.; Ford, T.; Jodrell, D. Cross-sectional survey of daily junk food consumption, irregular eating, mental and physical health and parenting style of British secondary school children. Child Care Health Dev. 2013, 40, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niemeier, H.; Raynor, H.; Lloyd-Richardson, E.; Rogers, M.; Wing, R. Fast food consumption and breakfast skipping: Predictors of weight gain from adolescence to adulthood in a nationally representative sample. J. Adolesc. Health 2006, 39, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wills, T.; Isasi, C.; Mendoza, D.; Ainette, M. Self-control constructs related to measures of dietary intake and physical activity in adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 41, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, D.; Beaver, K. The influence of neuropsychological deficits in early childhood on low self-control and misconduct through early adolescence. J. Crim. Justice 2013, 41, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, M.; DeLisi, M.; Beaver, K.; Wright, J.; Howard, M. Toward a psychopathology of self-control theory: The importance of narcissistic traits. Behav. Sci. Law 2007, 25, 803–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschi, T. Self-control and crime. In Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory, and Applications; Baumeister, R.F., Vohs, K.D., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wikstrom, P.; Treiber, K. The role of self-control in crime causation: Beyond gottfredson and hirschi’s general theory of crime. Eur. J. Criminol. 2007, 4, 237–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, N.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Hannan, P.; Story, M. Family meals during adolescence are associated with higher diet quality and healthful meal patterns during young adulthood. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 1502–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulkerson, J.; Story, M.; Mellin, A.; Leffert, N.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; French, S. Family dinner meal frequency and adolescent development: Relationships with developmental assets and high-risk behaviors. J. Adolesc. Health 2006, 39, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowry, R.; Wechsler, H.; Galuska, D.; Fulton, J.; Kann, L. Television viewing and its associations with overweight, sedentary lifestyle, and insufficient consumption of fruits and vegetables among US high school students: differences by race, ethnicity, and gender. J. School Health 2002, 72, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.; Cohen, P.; Smailes, E.; Kasen, S.; Brook, J. Television viewing and aggressive behavior during adolescence and adulthood. Science 2002, 295, 2468–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, N.; Biddle, S.J. Sedentary behavior and dietary intake in children, adolescents, and adults: A systematic review. Am. J. Prevent. Med. 2011, 41, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Weber, R.; Ritterfeld, U.; Mathiak, K. Does playing violent video games induce aggression? Empirical evidence of a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Media Psychol. 2006, 8, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaver, K.; Wright, J.; DeLisi, M.; Daigle, L.; Swatt, M.; Gibson, C. Evidence of a Gene X environment interaction in the creation of victimization: Results from a longitudinal sample of adolescents. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2007, 51, 620–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynie, D.; Piquero, E. Pubertal development and physical victimization in adolescence. J. Res. Crime Delinquency 2006, 43, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D. The role of early pubertal development in the relationship between general strain and juvenile crime. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2011, 10, 292–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffee, S.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.; Dodge, K.; Rutter, M.; Taylor, A.; Tully, L. Nature × nurture: Genetic vulnerabilities interact with physical maltreatment to promote conduct problems. Dev. Psychopathol. 2005, 17, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaccard, J.; Wan, C.K.; Turrisi, R. The detection and interpretation of interaction effects between continuous variables in multiple regression. Multivariate Behav. Res. 1990, 25, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMartin, S.; Jacka, F.; Colman, I. The association between fruit and vegetable consumption and mental health disorders: Evidence from five waves of a national survey of Canadians. Prev. Med. 2013, 56, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, J.; Boutwell, B. A demonstration of the generalizability of twin-based research on antisocial behavior. Behav. Genet. 2013, 43, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jackson, D.B.; Beaver, K.M. The Influence of Nutritional Factors on Verbal Deficits and Psychopathic Personality Traits: Evidence of the Moderating Role of the MAOA Genotype. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 15739-15755. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph121215017

Jackson DB, Beaver KM. The Influence of Nutritional Factors on Verbal Deficits and Psychopathic Personality Traits: Evidence of the Moderating Role of the MAOA Genotype. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015; 12(12):15739-15755. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph121215017

Chicago/Turabian StyleJackson, Dylan B., and Kevin M. Beaver. 2015. "The Influence of Nutritional Factors on Verbal Deficits and Psychopathic Personality Traits: Evidence of the Moderating Role of the MAOA Genotype" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12, no. 12: 15739-15755. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph121215017