Abstract

The aim of this study was to provide an overview of studies in which the impact of the 2008 economic crisis on child health was reported. Structured searches of PubMed, and ISI Web of Knowledge, were conducted. Quantitative and qualitative studies reporting health outcomes on children, published since 2007 and related to the 2008 economic crisis were included. Two reviewers independently assessed studies for inclusion. Data were synthesised as a narrative review. Five hundred and six titles and abstracts were reviewed, from which 22 studies were included. The risk of bias for quantitative studies was mixed while qualitative studies showed low risk of bias. An excess of 28,000–50,000 infant deaths in 2009 was estimated in sub-Saharan African countries, and increased infant mortality in Greece was reported. Increased price of foods was related to worsening nutrition habits in disadvantaged families worldwide. An increase in violence against children was reported in the U.S., and inequalities in health-related quality of life appeared in some countries. Most studies suggest that the economic crisis has harmed children’s health, and disproportionately affected the most vulnerable groups. There is an urgent need for further studies to monitor the child health effects of the global recession and to inform appropriate public policy responses.

1. Introduction

The current global economic and financial crisis, which began at the end of 2007 in the U.S., poses a major threat to health and affects mainly Europe and several other countries []. Economic downturns are known to affect health and living conditions of the populations. The impact of crisis in each country depends on the type of recession (duration and intensity, the speed of changes, and the types of changes that occur), the situation prior to the recession, the measures adopted by the states and governments in response to the crisis, and the role played by communities and family structure in the lives of individuals [].

There is a large body of work on recession and health, most of it in adults. There are both positive (i.e., road traffic accidents go down) and negative effects (i.e., suicides generally go up) documented []. There are fewer data for children and youth. Children are a vulnerable population group and strong evidence exists on the link between socioeconomic living conditions and child health []. The literature on previous recessions in different countries and periods suggest that exposure to poverty in early life and during childhood for prolonged periods may have a strong and irreversible impact on physical, cognitive and social health of the childhood population []. Exposure to poverty in early life has been shown to be associated with a higher risk of chronic health conditions of elderly people such as cardio-vascular diseases [,] and Alzheimer’s disease [,,].

The role of social determinants of health is essential in the pathways of influence of economic crisis on child health []. Reduced opportunities for employment increases income poverty, restrict food budget, decrease housing security/quality (e.g., via evictions and moves) and harm parental mental health []. Increased food costs restrict food budgets for all. Decreased spending on public services could lead to reduced health care provision, decreased social protection spending, and cuts in effective health promotion initiatives, including maternal health and early child development programmes. Child labour may increase with attendant impacts on health and education [,].

The level of social inequalities and social gradients during childhood in itself can also have an important role on health outcomes both in the short and the longer term []. Mechanisms of social protection (such as social welfare payments) implemented by countries are likely to be effective in mitigating the effects of economic shocks on child health [], but austerity measures adopted in many countries during the current economic crisis have reduced social protection mechanisms, thus potentially contributing to increased health inequalities [,]. Some studies have reported on the impact of the current economic crisis on families and children in Greece [], Spain [,], the UK [], and the U.S. []. In Greece youth unemployment rose from 18.6% to 40.1% from 2008 to 2011. In Spain, child poverty increased by 53% between 2007 and 2010. There are an estimated 3.5 million children living in poverty in the UK and this figure is expected to increase by 600,000 by 2015/2016 []. However, few data exist on the impact of the current economic crisis on child health so it is important to summarise what we know across studies reporting to date.

The objective of the present systematic review is to provide an overview of studies in which the impact of the 2008 economic and financial crisis on child health was analysed, in order to assess the evidence base to inform public health policy and identify research gaps.

2. Methods

A structured search was carried out in September 2013 in the databases PubMed, and ISI Web of Knowledge using terms for financial recession and terms for childhood. Languages included Dutch, English, French, Italian, Spanish, and Swedish. A Google search using the terms “crises OR downturn OR recession OR Economic Recession OR austerity AND child OR adolescent OR youth OR infant OR paediatrics” was also conducted, and the first 200 entries from Google were screened. All references lists of included studies were included, and an expert group, the International Network for Research in Inequalities in Child Health, were asked to identify any additional studies known to them.

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Both quantitative and qualitative studies were included, where they considered the impact of the current economic crisis on child health (children and young people <18 year). Longitudinal studies needed to compare a period before and after December 2007 (starting point of the current crisis), cross sectional studies needed to have collected data during the period 2008–2013. General population studies were included if results on the child population were identified separately. Outcomes included any mortalities, morbidities or wider child health impacts. Intermediate outcomes such as food consumption patterns were also considered given their potential for short and long term impacts on child nutrition and physical health. Studies on the impact of previous economic crises were excluded in the analysis as well as studies only analysing adult health. Given the scarcity of data, grey literature and none peer reviewed manuscripts were included if other selection criteria were fulfilled.

2.2. Study Selection

Abstracts obtained by the initial search strategy were assessed for possible inclusion by two researchers (L. Rajmil, M.J. Fernández de Sanmamed) and full text papers of all studies potentially includable (or unclear). Differences of opinion on inclusion were resolved by consensus.

2.3. Study Appraisal

The risk of bias of included studies was assessed by two authors (L. Rajmil, M.J. Fernández de Sanmamed) using the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) initiative for quantitative studies []. Qualitative studies were assessed using EPICURE (Engagement, Processing, Interpretation, Critique Usefulness, Relevance and Ethics) []. For quantitative studies, each criterion, from the total of 22, was awarded one point, 0.5 or 0 (Zero) points if adjudged to be fully, partially or not at all presented; studies scoring 16 or over were adjudged to have a low risk of bias; those scoring 7–15 as moderate risk, and those scoring <7 as high risk of bias. For qualitative studies, four out of the seven items (P, I, U, R) were considered essential to assess studies as average or low risk of bias (the latter if also met at least one of the other items). The lack of one or more of these four essential items was considered as high risk of bias. Given the scarcity of data on the study subject it was decided to avoid using quality assessment criteria as an exclusion criteria but to further carry out a sensitivity analysis and to assess the strengths of evidence of the included studies.

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

Data were extracted using a standardised data extraction form. Data extracted included: setting (according to the country: international, national or regional study); type of study (before-after comparative study, cross-sectional study, etc.); objectives of the study; years covered by the study; the specific target population; age range; exposure(s) measure(s) investigated (individual or ecologic variables such as unemployment rate, Gross Domestic Product, sociodemographic variables); outcome measures (classified as mortality, health-related quality of life, mental health, etc.); and the results in terms of impact on child health. The data was classified and organised according to the main outcome measure of the study. Quantitative and qualitative studies were analysed separately and the results presented together according to the outcome measure. Given the heterogeneity of studies in terms of study design (mainly observational and descriptive), participants, and outcomes, we undertook a narrative synthesis of the results. These are reported in the following categories: infant and child mortality; food habits and nutrition; health behaviours, non-accidental injuries, mental health and health-related quality of life; and chronic conditions.

3. Results

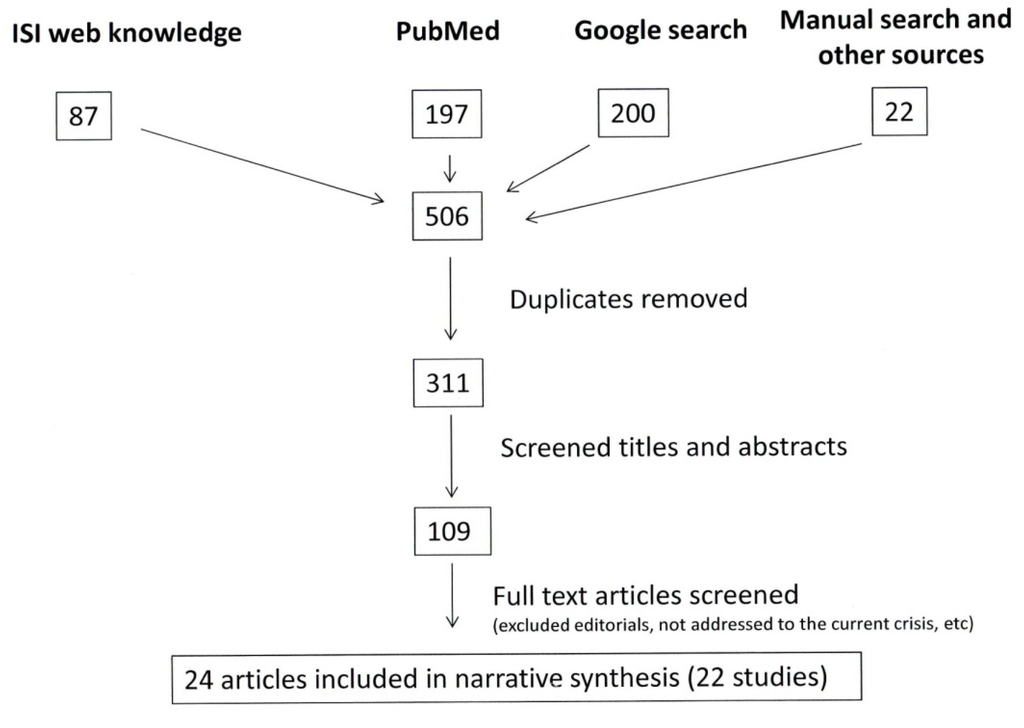

Figure 1 shows the results of the literature search. In all 506 documents were screened. From the 311 titles and abstracts reviewed 200 were initially excluded, most of them addressing previous crises and/or the impact on adult health; 109 documents were full text screened, and finally 24 documents corresponding to 22 studies were included (one study published three documents).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study selection process.

3.1. Study Characteristics

Nineteen quantitative studies, two qualitative studies and one study with mixed quantitative and qualitative methods were included in the review. Thirteen quantitative studies analysed trends over time [,,,,,,,,,,,,] and four of them showed a low risk of bias (Table 1) [,,,]. Six were cross-sectional studies [,,,,,] three of which showed a low risk of bias [,,]. Two qualitative studies were included: one was carried out in developing countries [,,], and one in the UK []. All except one qualitative sub-study [] showed low risk of bias on the EPICURE assessment. The study with mixed methods [] showed moderate risk of bias on its quantitative approach and low risk of bias on qualitative approach.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| First Author | Countries | Type of Study | Year(s) | Population/Sample | Source of Data (n) | Outcome Measure (s) | Risk of Bias (Score) " |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative studies: trends over time | |||||||

| Ariizumi [] | Canada | Mortality trends | 1977–2009 | All ages | Canadian Vital Statistics Data | Under 15 year mortality | 15 |

| Friedman [] | 30 Sub-Saharan African countries | Infant mortality trend modelisation | 2007–2009 | <1 year /Women 15–49 years old | Demographic Health Survey. Data from 260,000 women and 640,000 live births | Infant mortality | 16 |

| Simó [] | Greece, Spain, OECD "" countries | Infant, neonatal, and perinatal mortality trends | 1990–2010 | <1 year | OECD "" data on mortality | Infant, perinatal and neonatal | 7.5 |

| Vlachadis [] | Greece | Descriptive time-trends | 1966–2010 | All recorded live births and fetal deaths | Helenic Statistical Authority | Stillbirths per 1000 women | 7.5 |

| Gordon [] | UK | Cross-sectional survey and time trends description | Surveys conducted in 1982, 1990, 1999, 2012 | Children (ages not specified) | Necessities of Life survey (N = 2462 adults). Living standard survey (N = 5193 households) | Basic needs (30 items for children). Multiple deprivation | 14.5 |

| Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) [] | UK | Trends based on cross-sectional repeated surveys | 2007– 2011 | General population of households with children (ages not specified) | Family Food Survey (N = approximately 6000 households a year) | Household spending on food, and comparisons with healthy diet | 12.5 |

| Sulaiman [] | Bangladesh | Longitudinal rural panel and 2 urban cross sectional samples | 2006, 2008 | Children 0–59 months in 2006/24–82 months in 2008 | Nutritional project 2006. In 2008: subsample of 1163 rural households, and 435 urban households | Weight-for-height Z score in children. Changes of food consumption. | 12.5 |

| Berger [] | U.S. | Comparison before-during the recession | 2004–2007/December 2007–June 2009 | <5 year Population of 74 counties in 3 areas. | Incidence of AHT ‡ in children under 5 year. Hospital discharge records (N = 422) | Changes in rates of hospitalisation due to AHT | 20 |

| Huang [] | OH, U.S. | Incidence rates over time | 2001–November 2007/December 2007–June 2010 | <2 year | Incidence of injuries and AHT ‡. Hospital discharge records (N = 639). Study from 1 hospital | Changes in rates of hospitalisation due to AHT ‡ | 18 |

| Brooks-Gunn [] | U.S. | Prospective cohort study | May 2007–February 2010 | 9 year-old children | Wave of Fragile Families Child Well-being Study. 5000 families of 20 large cities from 15 States | Frequency of maternal spanking | 16 |

| Cui [] | U.S. | Trends based on repeated cross-sectional surveys | 2001–2010 U.S. general population sample | 12–17 year | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHAMES) | Self-rated health, unhealthy days and activity limitation days | 16 |

| Millet [] | U.S. | Before-after approach | 2001–2010 | Child under 18 year | Public available administrative data for 7 States | Child abuse and maltreatment reported to social services | 10 |

| Rajmil [] | Catalonia, Spain | Before-after approach | 2006–2010/2012 | 0–14 year General population | Catalan Health interview Survey 2006 (N = 2200) and Continuous health survey 2010–2012 (N = 1967) | Health behaviors, obesity, mental health and perceived heatlh and quality of life | 17 |

| Quantitative studies: cross sectional | |||||||

| Catalonian ombudsman [] | Catalonia, Spain | Cross-sectional | 2013 | <16 year General population from Catalonia | European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) and other sources | Reported food consumption. Multiple deprivation | 5.5 |

| Samuels [] | Nigeria | Cross sectional | 2009 | Households with children | National household surveys | Reported food consumption | 10 |

| Bruening [] | MN, U.S. | Cross-sectional | 2009–2010 Population-based study | Adolescents | Household Food Insecurity questionnaire (Families and Eating Activity Among Teens study) (N = 2095 parents) | Family food security status | 17 |

| Jackson [] | U.S. | Comparison of two cross-sectional studies | 2008–2010 | <18 year children with asthma and their parents | Behavioural Risk Factor Surveillance System phone interview (2008 N = 4133/2010 N =3492 parents) | Parental smoking behavior | 16 |

| Pearlman [] | U.S. | Cross-sectional | 2007–2009 | 2–17 year children with asthma | U.S. national Child Asthma Call-Back survey. Parents of children with asthma (N = 5138) | Level of asthma control | 13.5 |

| Tarantino [] | U.S. | Cross-sectional survey | 2009–2010 | <26 year Patients with haemophilia and their caregivers (where <26 year, average age = 11.2 year) Hematologists | Survey designed ad hoc (N = 70 caregivers of <26 year with Hemophilia A, and adult patients, N = 64) | Changes in treatment decision-making after downturn. Attitude towards healthcare reform | 16 |

| Anagnostopoulos [] | Greece | Descriptive cross sectional study | 2000–2011 | Child and adolescent population attending psychiatric services | National Action Plan Psychargos on mental healthcare services | Changes on the distribution of mental health diagnoses among users | 6 |

| Qualitative studies | |||||||

| Heltberg [] Hossain [] Hossain [] | Developing countries 17 in 2008, 6 in 2009, 4 in 2011 | Focus groups and interviews | 2008–2011 | Children (ages not specified. Respondents selected that represent groups exposed to economic shock) | To study perceptions and behaviors of people as live crisis impact and major coping responses used by poor and vulnerable people and households | EPICURe, EPICURe and epicURe respectively | |

| Samuels [] | Nigeria | Key informants interviews, focus groups and in-depth interviews | 2009 | Children (ages not specified) 6 Nigerian zones that reflect demographic and socioeconomic heterogeneity | To analyse the impact of 3F † crisis on vulnerable social groups (women and children) and coping strategies undertaken by households during the period of food, fuel and financial crisis | EPICURe | |

| Halls [] | UK | Semi-structured interviews and participant observation (Ethnographic approach) | December 2011 and January 2012 | Theoretically driven sample of 11 families with children (ages not specified) with different social status over 5 visits | To analyse the lived experience of families against a backdrop of austerity. Impact of austerity on family life and family food choices | ePIcURE | |

Notes: * The risk of bias was assessed using the STROBE criteria for quantitative studies (range 0–22 points); for qualitative studies the uppercase and lowercase indicate compliance or non-compliance (or absence) of a given item from the 7 items of the (see methods section for more information); ** OECD: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development; ‡ AHT Abussive head trauma; † 3F crisis: food, fuel and financial shock.

3.1.1. Infant and Child Mortality

Four studies reported mortality outcomes. One modelling study estimated an excess of 28,000–50,000 infant deaths in the year 2009 in sub-Saharan African countries based on interviews with a random sample of 260,000 mothers (Table 2) []. National vital statistics in Greece reported an increase of 32% in stillbirths between 2008 and 2010, and also increases in infant, perinatal and neonatal mortality [], while no influence was found on infant mortality in Spain [], or under 15 year mortality in Canada [].

Table 2.

Impact of the 2008 economic crisis on infant and child mortality.

| Countries | Results | Study |

|---|---|---|

| 30 Sub Saharan Africa Countries | Excess of 28,000–50,000 infant deaths in 2009, most of them girls (compared to period 1977–2008). There are 3 million infant deaths a year in these countries (infant mortality rate was 90/1000 in 2005). | Friedman J. [] |

| Greece, Spain | Perinatal, neonatal and infant mortality all increased by 20% to 30% from 2008 to 2010 in Greece. No changes were found for Spain. | Simó J. [] |

| Greece | Stillbirth rate increased from 3.31/1000 in 2008 to 4.28/1000 in 2009 and 4.36/1000 in 2010 (a 32% increase over 2 years). | Vlachadis N. [] |

| Canada | No influence of parental unemployment on mortality in children under 15 year when comparing the period 1977–2008 to 2009. | Ariizumi H. [] |

3.1.2. Food Habits and Nutrition

Four quantitative studies reported on the food habits and one on nutritional status, and there were three qualitative studies exploring food habits and nutrition (Table 3). Studies in Europe (Spain [] and UK []), U.S. [] and Bangladesh [] all demonstrated a significant adverse effect of the economic crisis on food intake by children, and specifically in vulnerable children. In particular the study in the UK by DEFRA [] showed a social gradient with children from low income families eating less fruit and vegetables between 2007 and 2011. A study in Bangladesh showed an increase in the number of children who were underweight [].

Qualitative studies found similar and consistent results both in developed and developing countries [,,,,]. The increase in food prices was associated to diminishing the number and quality of meals and buying cheaper food. A gender effect was noted since the results showed that more women were affected by the crisis compared to men. Poor children from urban areas in developing countries were affected the most []. The usual strategy followed by families was shown to be to reducing costs by giving foods based more on carbohydrates in developed and developing countries and fast food offered an easy solution according to the UK study [].

3.1.4. Chronic Conditions

Two studies reported on children with chronic conditions from the U.S. (see Table 5). A gap in health insurance coverage in the previous year was associated to a lower asthma control in children when comparing before and during the current crisis [].

Fifty four percent of hemophiliac patients or their caregivers reported negative impact on the management of the condition after starting the current crisis [].

Table 5.

Summary of the impact of the 2008 economic crisis on chronic conditions.

| Country | Results | Study |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. | Lack in health insurance coverage (OR = 1.74; 1.07–2.83) was the main factor associated to poorly controlled asthma during the period 2007–2009, together with intermediate-low income level. Higher levels of unemployment were not associated with asthma control. | Pearlman D.N. [] |

| U.S. | 54% reported negative impact on the management of the Hemophilia in the period 2009/2010 than previously: delayed or cancelled appointments, reduced or skipped doses, skipped filling prescription, delayed bleeding related urgent care visit. 22% anticipated positive influence of healthcare reform. | Tarantino M.D. [] |

4. Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first review on the effects of the 2008 economic crisis on children’s health. One modelling study estimated a negative impact on infant and child mortality in sub-Saharan countries; and in Greece such impact on mortality was shown by using registered data in another study. Furthermore, quantitative and qualitative studies documented changes in food consumption and nutrition worldwide with specific impact on most vulnerable population. Other studies showed an increase in non-accidental injuries and in social inequalities in perceived health and health-related quality of life in some countries. This review also highlights the gaps in knowledge on the subject and the need for studies to generate sufficient evidence to inform effective measures to mitigate the negative impact of the economic crisis on child health.

A limitation of the review is that most of the studies were not specifically designed to analyse the impact of economic crisis on child health, and are not sufficiently robust to establish a causal relationship. As a result, the level of evidence is weak to establish clear recommendations. Overall the quality of the studies is mixed, with a low likelihood of bias in the studies based on vital statistics or in population representative samples, but lower quality in others. A sensitivity analysis showed that child mortality studies were not of sufficient quality to demonstrate the impact of the crisis on mortality, (e.g., the outcomes estimated on the study from sub-Saharan African countries were based on retrospective data). Qualitative studies consistently showed increased nutritional risk of children of socially disadvantaged families worldwide. An increased risk of child maltreatment has been quite consistent in studies from the U.S., and inequalities in perceived health and quality of life were found in different populations. The rest of the results should be taken with great caution given the high or average risk of bias of the included studies. However, studies were included independently of their risk of bias due to the scarcity of data and to draw attention on the lack of good quality studies. Secondly, some studies present results as averages in the population. Future studies should focus on analysing the subgroups most affected by the crisis. Thirdly, publication bias cannot be ruled out. Fourthly, it should be taken into account that a diverse group of countries—both developed and developing—was included in the review. All these countries did not experience the recession at the same time and did not define it in the same way. As a consequence, some specific results such as infant mortality should not be generalised. Finally, characteristics of the included studies did not allow us to perform a meta-analysis.

Positive effects have been described on adult mortality in previous crises in some specific countries []. This effect has not been reported on child mortality either in previous or in the current crisis.

It is worth noting that none of the studies were ideally designed to demonstrate causal relationships. Nevertheless, some of the studies have tried to attribute a causal relationship to the recession making necessary adjustments to strengthen these claims (e.g., adjusting for pre-recession time trends, adjusting for other time varying confounders, among other procedures).

There is sufficient accumulated evidence from previous crises showing that exposure to situations of deprivation and increasing social inequalities are damaging to children's health in the short and long term. Cohort studies of children carried out since the last century have shown the influence of social determinants on physical, cognitive and social health [,,,], and the negative cumulative effects of deprivation and stress during the first years of life on the physical and mental health status later in childhood [,].

High food prices reduce diversity and nutritional quality of the diet, and even quantity []. This is likely to impact on the most vulnerable groups in both industrialised and developing countries. The poorest populations from urban areas are the most vulnerable to food insecurity and malnutrition []. In developed countries, children living in families without resources or without social protection mechanisms due to austerity measures are at greater nutritional risk, including both obesity and undernutrition. The results of the present review highlight the potential nutritional risk for the most vulnerable populations.

The evidence to date demonstrates the plausibility of the association between the crisis and violence against children. In the adult population, it has been found that mental health problems, family stress, violence and suicides increased in time of crisis [], and these often occur in families with children.

The included studies do not allow comparison of the measures taken by governments to alleviate the effects of the crisis, and this should be for a focus of future studies. Nevertheless, according to the present data, it cannot be ruled out that those countries adopting austerity measures showed high negative impact on child health, such as southern European countries. Future studies should confirm or discard this fact.

Implications for Research and Policy

Further research is required to establish the mechanisms by which an economic crisis affects children’s health, and how to measure the exposure. It should be taken into account that economic changes usually occur rapidly, leading to deterioration in the social determinants of health, but consequent changes in health outcomes can have long latency periods and may take decades to become fully apparent.

As currently available indicators are often not sensitive to the short-term impact on health, there is a need to develop indicators that are sensitive to change [,].

Cross country studies to assess the effects of the range of responses that have been implemented by governments during the recent economic crisis are needed and should include an assessment of effects on child health. Previous experience, such as the crisis in Nordic countries in the early 90s, suggested that no impact or a minimum impact on children's health occurred in Nordic countries given the protective effect of a highly developed welfare state and additional specific measures of child protection maintained during that crisis []. It is also necessary to study the epidemiology of resilience factors in order to determine the factors that mitigate the negative consequences of the crisis, including measures of social capital and family structure [].

5. Conclusions

Most studies suggest that the economic crisis may pose a serious threat to children’s health, and disproportionately affects the most vulnerable groups. There is an urgent need for further studies to monitor the child health effects of the global recession and to inform appropriate public policy responses.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the librarian Marta Millaret from the Catalan Agency for Health Quality and Assessment for her help in developing the search strategy. David Taylor-Robinson was supported by a Medical Research Council Population Health Scientist Fellowship to him (G0802448).

Author Contributions

Luis Rajmil conceptualized and designed the study, carried out the literature search, analyzed the data, and drafted the initial manuscript. María-José Fernández de Sanmamed, contributed to the study design, analyzed the data, and contributed to the first draft of the manuscript. Imti Choonara, Tomas Faresjö, Anders Hjern, Anita Kozyrskyj, Patricia Lucas, Hein Raat, Louise Séguin, Nick Spencer, and David Taylor-Robinson participated in the analysis, and contributed to the first draft of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Karanikolos, M.; Mladovsky, Ph.; Cylus, J.; Thomson, S.; Basu, S.; Stuckler, D.; Mackenbach, J.P.; McKee, M. Financial crisis, austerity, and health in Europe. Lancet 2013, 381, 1323–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, A.; Blakey, E. Crisis económica y desigualdades en salud (Economic crisis and health inequalities), Colección de Minitemas Online de la Escuela Nacional de Sanidad; Instituto de Salud Carlos III: Madrid, Spain, 2012. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Suhrcke, M.; Stuckler, D. Will the recession be bad for our health? It depends. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early Child Development Knowledge Network (ECDKN). In Early Child Development: A Powerful Equalizer; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Children and Youth in Crisis Protecting and Promoting Human Development in Times of Economic Shocks; Lundberg, M.; Wuermli, A. (Eds.) The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Harper, S.; Lynch, J.; Smith, G.D. Social determinants and the decline of cardiovascular diseases: Understanding the links. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2011, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollitt, R.A.; Rose, K.M.; Kaufman, J.S. Evaluating evidence for models of life course socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2005, 5, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Janicki-Deverts, D.; Chen, E.; Matthews, K.A. Childhood socioeconomic status and adult health. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1186, 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, G.A.; Turrell, G.; Lynch, J.W.; Everson, S.A.; Helkala, E.L.; Salonen, J.T. Childhood socioeconomic position and cognitive function in adulthood. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 30, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, W.J.; Linver, M.R.; Brooks-Gunn, J. How money matters for young children’s development: Parental investment and family processes. Child Develop. 2002, 73, 1861–1879. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, N. Reducing child health inequalities: What’s the problem? Arch. Dis. Child. 2013, 98, 836–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, C.D.; López-Valcárcel, B.G. The economic crisis and health. Gac. Sanit. 2009, 4, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, R.; Gavrilovic, M. The Impacts of the Economic Crisis on Youth: Review of Evidence; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Starfield, B. Social Gradients and Child Health; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Health Equity UCL. The Impact of the Recession and Welfare Changes on Health Inequalities. Available online: https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/themes/work-on-recession-and-welfare-changes (accessed on 14 August 2013).

- Kentikelenis, A.; Karanikolos, M.; Papanicolas, I.; Basu, S.; McKee, M.; Stuckler, D. Health effects of financial crisis: Omens of a Greek tragedy. Lancet 2011, 378, 457–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Bueno, G.; Bellos, A.; Arias, M. La infancia en España 2012–2013, El impacto de la Crisis en los Niños; UNICEF España: Madrid, Spain, 2012. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- El Impacto de la Crisis en Las Familias y en la Infancia; Navarro, V.; Clua-Losada, M. (Eds.) Observatorio Social de España: Barcelona, Spain, 2012.

- Withham, G. Child Poverty in 2012: It Shouldn’t Happen Here; Save the Children: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, P. Children of the recession. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2009, 163, 1063–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child Poverty Action Group. Child Poverty Facts and Figures. Available online: http://www.cpag.org.uk/child-poverty-facts-and-figures (accessed on 16 November 2013).

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbrouckef, J.P.; for the STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bull. WHO 2007, 85, 867–872. [Google Scholar]

- Stige, B.; Malterud, K.; Midtgarden, T. Toward an agenda for evaluation of qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 2009, 19, 1504–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariizumi, H.; Schirle, T. Are recessions really good for your health? Evidence from Canada. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 1224–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.; Schady, N. How many infants likely died in Africa as a result of the 2008–2009 global financial crisis? Health Economics 2013, 22, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simó, J. Los Niños, Primeras Víctimas Mortales de la Crisis en Grecia. Available online: http://saluddineroy.blogspot.com.es/2013/02/los-ninos-primeras-victimas-mortales-de.html?spref=tw (accessed on 21 June 2013).

- Vlachadis, N.; Kornarou, E. Increase in still births in Greece is linked to the economic crisis. BMJ 2013, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.; Mack, J.; Lansley, S.; Mack, J.; Main, G.; Nandy, S.; Patsios, D.; Pomati, M. The Impoverishment of the UK; Poverty and Social Exclusion (PSE): Bristol, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Exploratory Analysis and Trends Informing Policy. In Family, Food 2011; Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA): London, UK, 2012; Chapter 5.

- Sulaiman, M.; Parveen, M.; Das, N.C. Impact of the Food Price Hike on Nutritional Status of Women and Children; Research and Evaluation Division: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, R.P.; Fromkin, J.B.; Stutz, H.; Makoroff, K.; Scribano, P.H.; Feldman, K.; Tu, L.C.; Fabio, A. Abusive head trauma during a time of increased unemployment: A multicenter analysis. Pediatrics 2011, 128, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.I.; O’Riordan, M.A.; Fitzenrider, E.; McDavid, L.; Cohen, A.R.; Robinson, S. Increased incidence of nonaccidental head trauma in infants associated with the economic recession. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2011, 8, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks-Gunn, J.; Schneider, W.; Walfogel, J. The great recession and the risk for child maltreatment. Child Abuse Neglect 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Zack, M.M. Trends in health-related quality of life among adolescents in the United States, 2001–2010. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millet, L.; Lanier, P.; Drake, B. Are socioeconomic trends associated with maltreatment? Preliminary results from the recent recession using state level data. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 1280–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajmil, L.; Medina-Bustos, A.; de Sanmamed, M.J.F.; Mompart, A. Impact of the economic crisis on children’s health in Catalonia: A before-after approach. BMJ Open 2013, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Síndic de Greuges de Catalunya (Catalonian Ombudsman). In Informe Sobre la Malnutrició Infantil a Catalunya; (in Spanish). Síndic de Greuges: Barcelona, Spain, 2013.

- Bruening, M.; MacLehose, R.; Loth, K.; Story, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Feeding a family in a recession: Food insecurity among Minnesota parents. Amer. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T.L.; Gjelsvik, A.; Garro, A.; Pearlman, D.N. Correlates of smoking during an economic recession among parents of children with asthma. J. Asthma 2013, 50, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlman, D.N.; Jackson, T.L.; Gjelsvik, A.; Viner-Brown, S.; Garro, A. The impact of the 2007–2009 U.S. recession on the health of children with asthma: Evidence from the national Child Asthma Call-back Survey. R. I. Med. J. 2012, 95, 394–396. [Google Scholar]

- Tarantino, M.D.; Ye, X.; Bergstrom, F.; Skorija, K.; Luo, M.P. The impact of economic downturn and health care reform on treatment decisions for Hemophilia A: Patient, caregiver and health care provider perspectives. Haemophilia 2013, 19, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, D.C.; Soumaki, E. The state of child and adolescent psychiatry in Greece during the international financial crisis: A brief report. Eur. Chid. Adolesc. Psychiatr. 2013, 22, 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Living through Crises: How the Food, Fuel, and Financial Shocks Affect the Poor; Heltberg, R.; Hossain, N.; Reva, A. (Eds.) World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Hossain, N.; Eyben, R. Accounts of Crisis: Poor People’s Experiences of the Food, Fuel and Financial Crises in Five Countries; Institute of Development Studies: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, N.; McGregor, J.A. A “Lost Generation”? Impacts of complex compound crises on children and young people. Dev. Policy Rev. 2011, 29, 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.; Perry, C. Family Matters: Understanding Families in an Age of Austerity; Social Research Institute: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, F.; Gavrilovic, M.; Harper, C.; Niño-Zarazua, M. Food, Finance and Fuel: The Impacts of the Triple F Crisis in Nigeria, with a Particular Focus on Women and Children; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, M.; Bilal, U.; Orduñez, P.; Benet, M.; Morejón, A.; Caballero, B.; Kennelly, J.F.; Cooper, R.S. Population-wide weight loss and regain in relation to diabetes burden and cardiovascular mortality in Cuba 1980–2010: Repeated cross sectional surveys and ecological comparison of secular trends. BMJ 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, L. Inequality in the early cognitive development of British children in the 1970 cohort. Economica 2003, 70, 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.A.; Egerter, S.A.; Mockenhaupt, R.E. Broadening the focus: The need to address the social determinants of health. Amer. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 40, S4–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S.; Lynch, J.; Smith, G.D. Social determinants and the decline of cardiovascular diseases: Understanding the links. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2011, 32, 39–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.; Egerter, S.; Williams, D.R. The social determinants of health: Coming of age. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2011, 32, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séguin, L.; Nikiéma, B.; Gauvin, L. Childhood Poverty, Cumulative Adversities and, Chronic Health Conditions at 10 Years Old in the Quebec Birth Cohort; APHA: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, N.; Tu, M.T.; Séguin, L. Low income/socio-economic status in early childhood and physical health in later childhood/adolescence: A systematic review. Matern. Child Health J. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pee, S.; Brinkman, H.J.; Webb, P.; Godfrey, S.; Darnton-Hill, I.; Alderman, H.; Semba, R.D.; Piwoz, E.; Bloem, M.W. How to ensure nutrition security in the global economic crisis to protect and enhance development of young children and our common future. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, S138–S142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruel, M.T.; Garret, J.; Hawkwa, C.; Cohen, M.J. The food, fuel, and financial crisis affect the urban and rural poor disproportionately: A review of evidence. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, S170–S176. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Bernal, J.A.; Gasparrini, A.; Artundo, C.M.; McKee, M. The effect of the late 2000s financial crisis on suïcides in Spain: An interreupted time-series analysis. Eur. J. Public Health 2013, 23, 732–736. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M. Mortality rates or sociomedical indicators? The work of the League of Nations on standardizing the effects of the great depression on health. Health Policy Plann. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremberg, S. Does an increase of low income families affect child health inequalities? A Swedish case study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2003, 57, 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).