What are the Benefits of Interacting with Nature?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Selection of Articles for Review

2.2. Typology of Settings

| Setting | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Indoor | Inside a building | Foliage plants [35,36] |

| Urban | Landscape dominated by built form | Public green space [37] |

| Private green space e.g., garden [38] | ||

| Roadside trees or isolated urban vegetation [39] | ||

| Fringe | The area immediately surrounding a town or city | Peri-urban nature reserve [37] |

| Production Landscape | Agricultural lands (pastoral or cropping) | Paddocks/fields/countryside [10] |

| Wilderness | Area where human influence is low | Beach [40] |

| Ocean [41] | ||

| River [42,43] | ||

| Water [44,45] | ||

| Mountains [46] | ||

| Forest/woodland [47] | ||

| National Parks [48,49,50] | ||

| Specific species | Cases where object of the interaction is defined with no particular setting | Marine animals [41,51] |

| Avian [41] | ||

| Domesticated pets [52] |

2.3. Typology of Interactions

| Interaction | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Indirect | Experiencing nature while not being physically present in it | Viewing nature in a picture, image, motion picture or through a window [13,57] |

| Incidental | Experiencing nature as a by-product of another activity | Encountering nature incidental to another activity, e.g., walking to work or driving [39] |

| Encountering vegetation indoors [58] | ||

| Intentional | Experiencing or being in nature through direct intention | Recreation, e.g., hiking, camping, wildlife viewing, adventure |

| Gardening or farming [16] | ||

| Conservation volunteering [47] |

2.4. Typology of Benefits

| Benefit | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Psychological well-being | Positive effect on mental processes | Increased self-esteem [32,60,61] |

| Improved mood [58,32] | ||

| Reduced anger/frustration [62] | ||

| Psychological well-being [13,63,64] | ||

| Reduced anxiety [65] | ||

| Improved behaviour [15] | ||

| Cognitive | Positive effect on cognitive ability or function | Attentional restoration [12,14,46,66,67] |

| Reduced mental fatigue [63] | ||

| Improved academic performance [68] | ||

| Education/learning opportunities [49,55] | ||

| Improved ability to perform tasks [15] | ||

| Improved cognitive function in children [69] | ||

| Improved productivity [35,68] | ||

| Physiological | Positive effect on physical function and/or physical health | Stress reduction [37,70,71] |

| Reduced blood pressure [45,32] | ||

| Reduced cortisol levels [70] | ||

| Reduced headaches [37] | ||

| Reduced mortality rates from circulatory disease [24] | ||

| Faster healing [9] | ||

| Addiction recovery [43] | ||

| Perceived health/well-being [59] | ||

| Reduced cardiovascular, respiratory disease and long-term illness [11] | ||

| Reduced occurrence of illness [15,35] | ||

| Social | Positive social effect at an individual, community or national scale | Facilitated social interaction [72,73] |

| Enables social empowerment [62,74] | ||

| Reduced crime rates [25] | ||

| Reduced violence [63] | ||

| Enables interracial interaction [16] | ||

| Social cohesion [72] | ||

| Social support [72] | ||

| Spiritual | Positive effect on individual religious pursuits or spiritual well being | Increased inspiration [42] |

| Increased spiritual well-being [41,47] | ||

| Tangible | Material goods that an individual can accrue for wealth or possession | Food supply [38] |

| Money [50,75] |

3. Results and Discussion

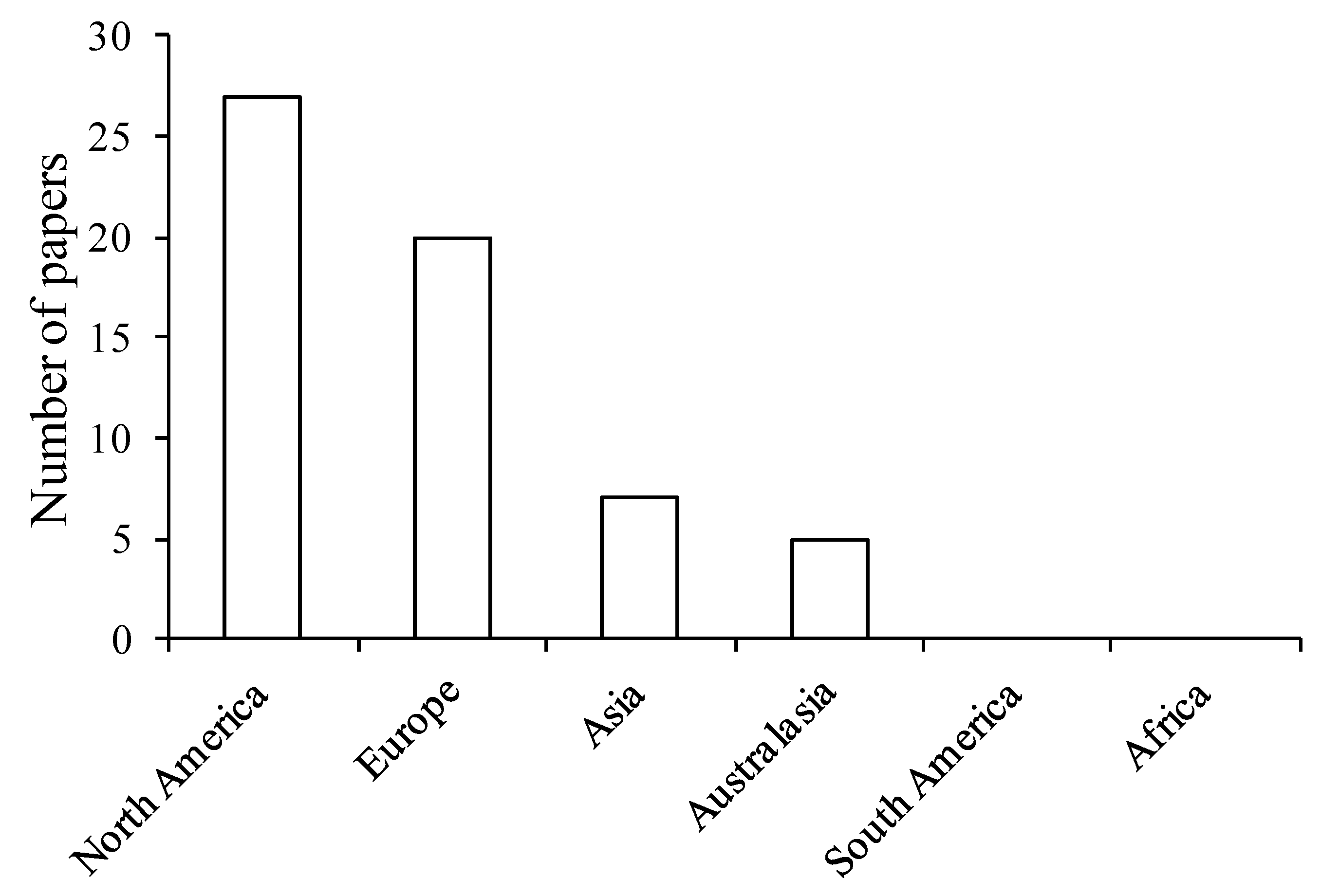

3.1. Geographical Bias

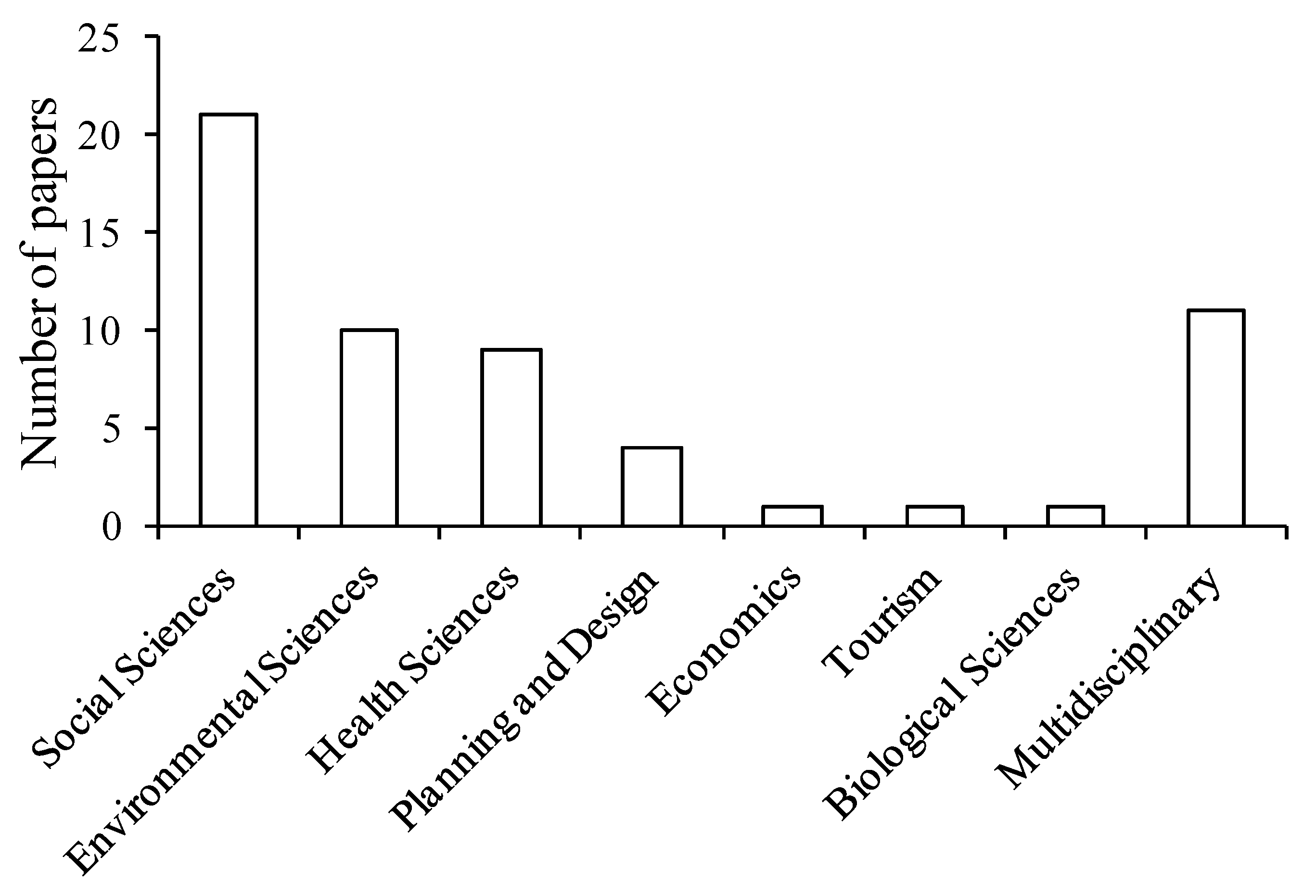

3.2. Disciplinary Representation in Nature-Interaction Benefits Research

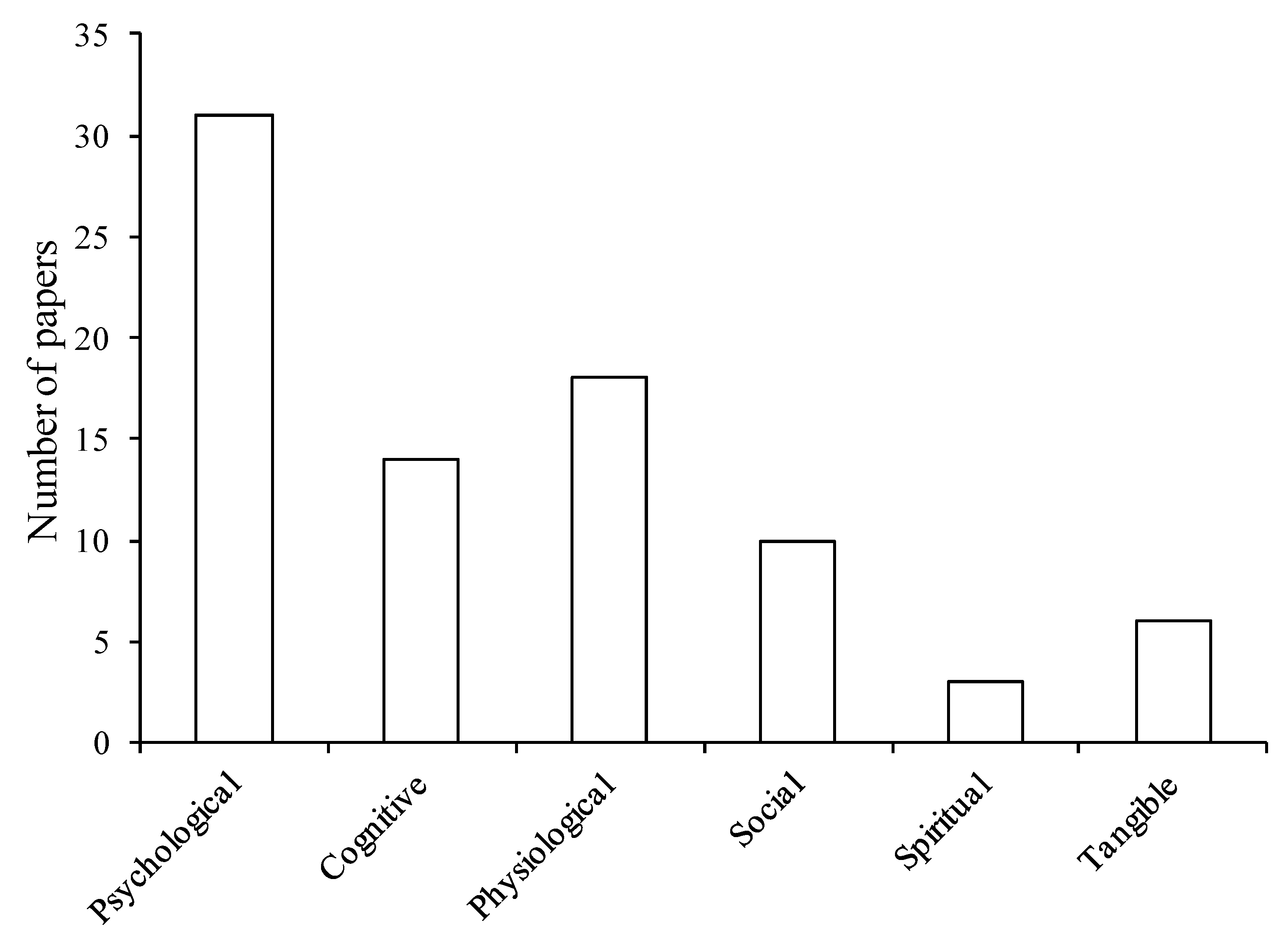

3.3. Strength of Evidence for the Benefits of Interacting with Nature

3.3.1. Psychological Well-Being Benefits

3.3.2. Cognitive Benefits

3.3.3. Physiological Benefits

3.3.4. Social Benefits

3.3.5. Spiritual Benefits

3.3.6. Tangible Benefits

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- Fuller, R.A.; Irvine, K.N. Interactions between People and Nature in Urban Environments. In Urban Ecology; Gaston, K.J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 134–171. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, K.N.; Fuller, R.A.; Devine-Wright, P.; Payne, S.; Tratalos, J.; Warren, P.; Lomas, K.J.; Gaston, K.J. Ecological and Psychological Value of Urban Green Space. In Dimensions of the Sustainable City; Jenks, J., Jones, C., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 215–237. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Aldous, D.E. Social, environmental, economic, and health benefits of green spaces. Acta Hort. 2007, 762, 171–184. [Google Scholar]

- Thoreau, H.D. Walden; Ticknor and Fields: Boston, MA, USA, 1854. [Google Scholar]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.M.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, K.N.; Warber, S.L. Greening Healthcare: Practicing as if the natural environment really mattered. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2002, 8, 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, J. How nature contributes to mental and physical health. Spirit. Health Int. 2004, 5, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar]

- Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P.; de Vries, S.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Green space, urbanity, and health: How strong is the relation? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, E.A.; Mitchell, R. Gender differences in relationships between urban green space and health in the United Kingdom. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, M.; Hartig, T. Does the outdoor environment matter for psychological restoration gained through running? Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2001, 2, 141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R. The nature of the view from home: Psychological benefits. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 507–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R.A.; Irvine, K.N.; Devine-Wright, P.; Warren, P.H.; Gaston, K.J. Psychological benefits of greenspace increase with biodiversity. Biol. Lett. 2007, 3, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K. Influence of limitedly visible leafy indoor plants on the psychology, behaviour, and health of students at a junior high school in Taiwan. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 658–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinew, K.J.; Glover, T.D.; Parry, D.C. Leisure spaces as potential sites for interracial interaction: Community gardens in urban areas. J. Leisure Res. 2004, 36, 336–355. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, W.S.; Yeoun, P.S.; Yoo, R.W.; Shin, C.S. Forest experience and psychological health benefits. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansem-Ketchum, P.; Marck, P.; Reutter, L. Engaging with nature to promote health: New directions for nursing research. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 1527–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maller, C.; Townsend, M.; Pryor, A.; Brown, P.; St Leger, L. Healthy nature healthy people: “Contact with nature” as an upstream health promotion intervention for populations. Health Promot. Int. 2006, 21, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, H. Healthy places: Exploring the evidence. Amer. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, S.B.; Wolen, A.R. The benefits of human-companion animal interaction: A review. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2008, 35, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringslimark, T.; Hartig, T.; Patil, G.G. The psychological benefits of indoor plants: A critical review of the experimental literature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Grant, M. Biodiversity and human health: What role for nature in healthy urban planning? Built Environ. 2005, 31, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.; Popham, F. Effect of exposure to natural environment on health inequalities: An observational population study. Lancet 2008, 372, 1655–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, F.E.; Sullivan, W.C. Environment and crime in the inner city: Does vegetation reduce crime. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 343–367. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, A.G. Latitudinal variations in organic diversity. Evolution 1960, 14, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakes, E.H.; Mace, G.M.; McGowan, P.J.K.; Fuller, R.A. Extreme contagion in global habitat clearance. Proc. Roy. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 277, 1081–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasturiratne, A.; Wickremasinghe, A.R.; de Silva, N.; Gunawardena, N.K.; Pathmeswaran, A.; Premaratna, R.; Savioli, L.; Lalloo, D.G.; de Silva, H.J. The global burden of snakebite: A literature analysis and modelling based on regional estimates of envenoming and deaths. PLoS Med. 2008, 5, e218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, D.; Mutua, F.; Ochungo, P.; Kruska, R.; Jones, K.; Brierley, L.; Lapar, L.; Said, M.; Herrero, M.; Phuc, P.M.; Thao, N.B.; Akuku, I.; Ogutu, F. Mapping of Poverty and Likely Zoonoses Hotspots. Zoonoses Project 4. Report to the UK Department for International Development; International Livestock Research Institute: Nairobi, Kenya, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Teel, T.L.; Manfredo, M.J.; Stinchfield, H.M. The need and theoretical basis for exploring wildlife value orientations cross-culturally. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2007, 12, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warber, S.L.; Irvine, K.N. Relationship between People and Plants. In Natural Products from Plants, 2nd; Cseke, L.J., Kirakosyan, A., Kaufman, P., Warber, S., Duke, J.A., Brielmann, H., Eds.; CRC Press/Taylor and Francis Group, LLC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; pp. 535–546. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, J.; Peacock, J.; Sellens, M.; Griffin, M. The mental and physical health outcomes of green exercise. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2005, 15, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, K.N.; Warber, S.L.; Devine-Wright, P.; Gaston, K.J. Understanding urban green space as a health resource: A qualitative comparison of visit motivation and derived effects among park users in Sheffield, UK. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 417–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Wilson, C.; McCullum, C.; Huang, R.; Dwen, P.; Flack, J.; Tran, Q.; Saltman, T.; Cliff, B. Economic and environmental benefits of biodiversity. BioScience 1997, 47, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringslimark, T.; Hartig, T.; Patil, G.G. Psychological benefits of indoor plants in workplaces: Putting experimental results into context. HortScience 2007, 42, 581–587. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, K.; Pieterse, M.E.; Pruyn, A. Stress-reducing effects of indoor plants in the built healthcare environment: The mediating role of perceived attractiveness. Prev. Med. 2008, 47, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmann, R.; Hug, S.; Seeland, K. Restoration and stress relief through physical activities in forests and parks. Urban Forestry Urban Greening 2007, 6, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. Some psychological benefits of gardening. Environ. Behav. 1973, 5, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cackowski, J.M.; Nasar, J.L. The restorative effects of roadside vegetation: Implications for automobile driver anger and frustration. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 736–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.; Dixon, A.W.; Mjelde, J.W.; Draper, J. Valuing visitors’ economic benefits of public beach access points. Ocean Coast. Manage. 2008, 51, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtin, S. Wildlife tourism: The intangible, psychological benefits of human-wildlife encounters. Curr. Issues Tourism 2009, 12, 451–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, L.M.; Anderson, D.H. A qualitative exploration of the wilderness experience as a source of spiritual inspiration. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, L.W.; Cardone, S.; Jarczyk, J. Effects of a therapeutic camping program on addiction recovery. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1998, 15, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Natural versus urban scenes: Some psychophysiological effects. Environ. Behav. 1981, 13, 523–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Mang, M.; Evans, G.W. Restorative effects of natural environment experiences. Environ. Behav. 1991, 23, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.; Harvey, D. Transcendent experience in forest environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransom, K.P.; Mangi, S.C. Valuing recreational benefits of coral reefs: The case of Mombasa Marine National Park and Reserve, Kenya. Environ. Manage. 2008, 45, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.S.; Jaakson, R.; Kim, E.I. Benefits-based analysis of visitor use of Sorak-San National Park in Korea. Environ. Manage. 2001, 28, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, L.J.; Tisdell, C.; Lisle, A.T. The impact of Noosa National Park on surrounding property values: An application of the hedonic price method. Econ. Anal. Pol. 2002, 32, 155–171. [Google Scholar]

- Zeppel, H. Education and conservation benefits of marine wildlife tours: Developing free choice learning experiences. J. Environ. Educ. 2008, 39, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpell, J. Beneficial effects of pet ownership on some aspects of human health and behaviour. J. Roy. Soc. Med. 1991, 84, 717–720. [Google Scholar]

- Lepczyk, C.A.; Mertig, A.G.; Liu, J. Assessing landowner activities related to birds across rural-to-urban landscapes. Environ. Manage. 2004, 33, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaston, K.J.; Fuller, R.A.; Loram, A.; MacDonald, C.; Power, S.; Dempsey, N. Urban domestic gardens (XI): Variation in urban wildlife gardening in the United Kingdom. Biodivers. Conserv. 2007, 16, 3227–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Domesticated nature: Motivations for gardening and perceptions of environmental impact. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Myers, G. Conservation Psychology: Understanding and Promoting Human Care for Nature; Wiley-Blackwell: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Leather, P.; Pyrgas, M.; Beale, D.; Lawrence, C. Windows in the workplace: Sunlight, view and occupational stress. Environ. Behav. 1998, 30, 739–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, S.; Suzuki, N. Effects of the foliage plant on task performance and mood. J. Environ. Psychol. 2002, 22, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bixler, R.D.; Floyd, M.F. Nature is scary, disgusting and uncomfortable. Environ. Behav. 1997, 29, 443–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. Some psychological benefits of an outdoor challenge program. Environ. Behav. 1974, 6, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maller, C.J. Promoting children’s mental, emotional and social health through contact with nature: A model. Health Educ. 2009, 109, 522–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, F.E.; Sullivan, W.C. Aggression and violence in the inner city: Effects of environment via mental fatigue. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.; Townsend, M.; Oldroyd, J. Linking human and ecosystem health: The benefits of community involvement in conservation groups. EcoHealth 2007, 3, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catanzaro, C.; Ekanem, E. Home gardeners value stress reduction and interaction with nature. Acta Hort. 2004, 639, 269–275. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.; Chen, P. Human response to window views and indoor plants in the workplace. HortScience 2005, 40, 1354–1359. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, T.R.; Black, A.M.; Fountaine, K.A.; Knotts, D.J. Reflection and attentional recovery as distinctive benefits of restorative environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1997, 17, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K. An exploration of relationships among the responses to natural scenes: Scenic beauty, preference and restoration. Environ. Behav. 2010, 42, 243–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjeld, T.; Veiersted, B.; Sandvik, L.; Riise, G.; Levy, F. The effect of indoor foliage plants on health and discomfort symptoms among office workers. Indoor Built Environ. 1998, 2, 204–209. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, N.M. At home with nature: Effects of “greenness” on children’s cognitive functioning. Environ. Behav. 2000, 32, 775–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, A.E.; Custers, M.H.G. Gardening promotes neuroendocrine and affective restoration from stress. J. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Deguchi, M.; Miyazaki, Y. The effects of exercise in forest and urban environments on sympathetic nervous activity of normal young adults. J. Int. Med. Res. 2006, 34, 152–159. [Google Scholar]

- Kingsley, J.; Townsend, M. “Dig in” to social capital: Community gardens as mechanisms for growing urban social connectedness. Urban Pol. Res. 2006, 24, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coley, R.L.; Sullivan, W.C.; Kuo, F.E. Where does community grow?: The social context created by nature in urban public housing. Environ. Behav. 1997, 29, 468–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, L.M. Urban greening and social benefits: A study of empowerment outcomes. J. Arboric. 2003, 29, 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bolitzer, B.; Netusil, N.R. The impact of open spaces on property values in Portland, Oregon. J. Environ. Manage. 2000, 59, 185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Jim, C.Y.; Chen, W.Y. Perception and attitude of residents toward urban green spaces in Guangzhou (China). Environ. Manage. 2006, 38, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Peacock, J.; Hine, R.; Sellens, M.; South, N.; Griffin, N. Green exercise in the UK countryside: Effects on health and psychological well-being, and implications for policy and planning. J. Environ. Plann. Manag. 2007, 50, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.H.; Fujiyama, H.; Sugano, A.; Okamura, T.; Chang, M.; Onouha, F. Psychological responses to exercising in laboratory and natural environments. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2006, 7, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohr, V.I.; Pearson-Mims, C.H. Children’s active and passive interactions with plants influence their attitudes as actions toward trees and gardening as adults. HortTechnology 2005, 15, 472–476. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, L. Life paths into effective environmental action. J. Environ. Educ. 1999, 31, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyle, R.M. Nature matrix: Reconnecting people and nature. Oryx 2003, 37, 206–214. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, L. Significant life experiences revisited: A review of research on sources of environmental sensitivity. Environ. Educ. Res. 1998, 4, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.R. Biodiversity conservation and the extinction of experience. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samways, M.J. Rescuing the extinction of experience. Biodivers. Conserv. 2007, 16, 1995–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A. The Nature Relatedness Scale. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 715–740. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: Measuring endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, M.G.; Jonides, J.; Kaplan, S. The cognitive benefits of interacting with nature. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Kaiser, F.G.; Strumse, E. Psychological restoration in nature as a source of motivation for ecological behaviour. Environ. Conserv. 2007, 34, 291–299. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A.F.; Kuo, F.E.; Sullivan, W.C. Coping with ADD: The surprising connection to green play settings. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, L.; Adams, J.; Deal, B.; Kweon, B.S.; Tyler, E. Plants in the workplace: The effects of plant density on productivity, attitudes, and perceptions. Environ. Behav. 1998, 30, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Council of the Netherlands and Dutch Advisory Council for Research on Spatial Planning, Nature and the Environment. In Nature and Health: The Influence of Nature on Social, Psychological and Physical Well-being; Health Council of the Netherlands and RMNO: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2004.

- Orams, M.B. Feeding wildlife as a tourism attraction: A review of issues and impacts. Tourism Manag. 2002, 23, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawk, S.R.; Hull, M.I.; Thalman, R.I.; Richins, P.M. Review of spiritual health: Definitions, role and intervention strategies in health promotion. Am. J. Health Promot. 1995, 9, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuefle, D.M. The spirituality of recreation. Parks Recreation 1999, 34, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Warber, S.L.; Irvine, K.N. Nature and Spirit. In Measuring the Immeasurable; Sounds True, Inc.: Boulder, CO, USA, 2008; pp. 135–155. [Google Scholar]

- Morancho, A.B. A hedonic valuation of urban green areas. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2003, 66, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troy, A.; Grove, J.M. Property values, parks, and crime: A hedonic analysis in Baltimore, MD. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2008, 87, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleyar, M.D.; Greve, A.I.; Withey, J.C.; Bjorn, A.M. An integrated approach to evaluating urban forest functionality. Urban Ecosyst. 2008, 11, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibnik, M. The value of subsistence production. J. Anthropol. Res. 1978, 34, 561–576. [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Biodiversity Synthesis; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- Pyle, R.M. The extinction of experience. Horticulture 1978, 56, 64–67. [Google Scholar]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Keniger, L.E.; Gaston, K.J.; Irvine, K.N.; Fuller, R.A. What are the Benefits of Interacting with Nature? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 913-935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10030913

Keniger LE, Gaston KJ, Irvine KN, Fuller RA. What are the Benefits of Interacting with Nature? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2013; 10(3):913-935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10030913

Chicago/Turabian StyleKeniger, Lucy E., Kevin J. Gaston, Katherine N. Irvine, and Richard A. Fuller. 2013. "What are the Benefits of Interacting with Nature?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 10, no. 3: 913-935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10030913

APA StyleKeniger, L. E., Gaston, K. J., Irvine, K. N., & Fuller, R. A. (2013). What are the Benefits of Interacting with Nature? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10(3), 913-935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10030913