Tailoring the Properties of Marine-Based Alginate Hydrogels: A Comparison of Enzymatic (HRP) and Visible-Light (SPS/Ruth)-Induced Gelation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Result and Discussion

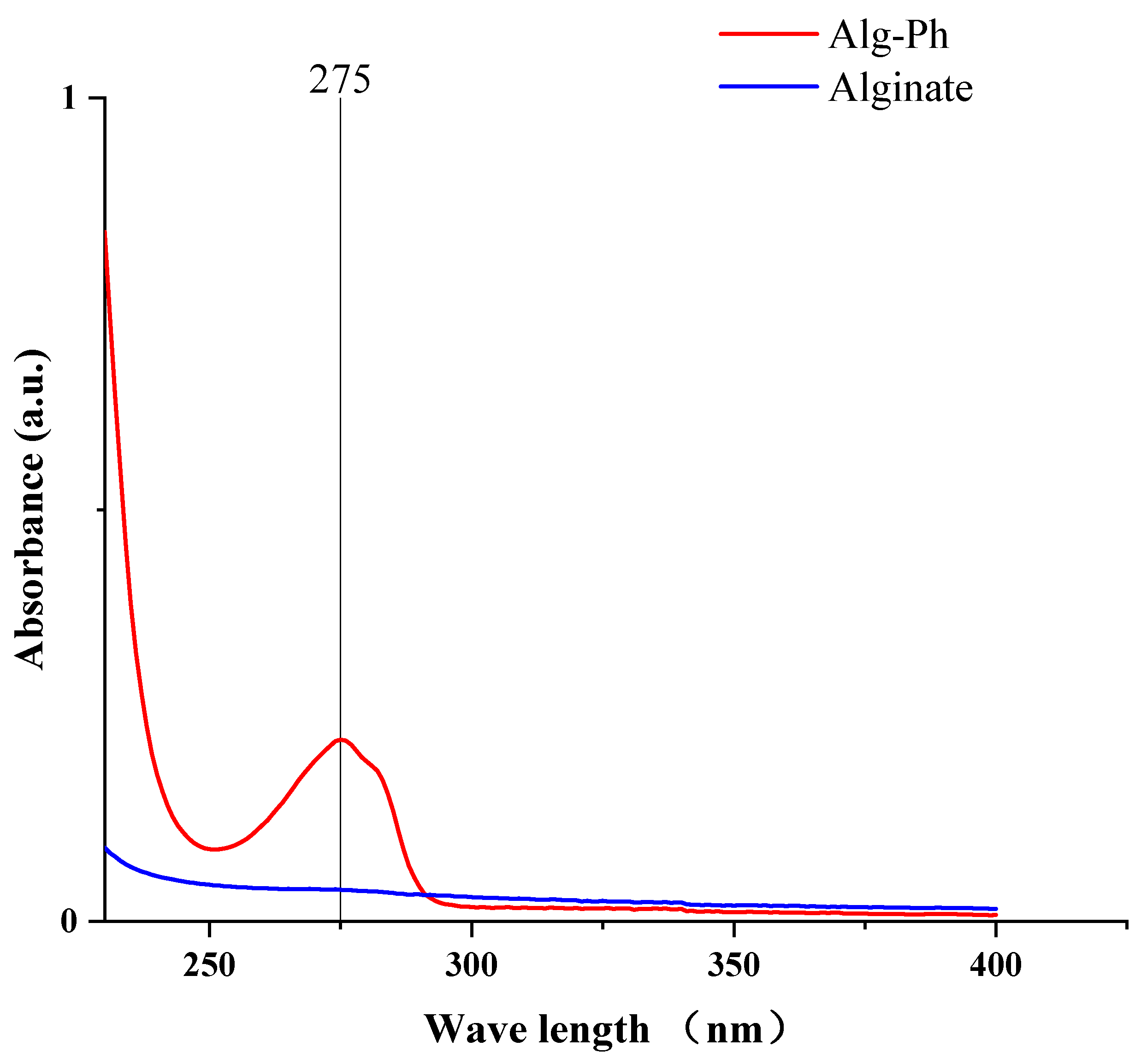

2.1. UV-Absorbance of the Alginate Derivative

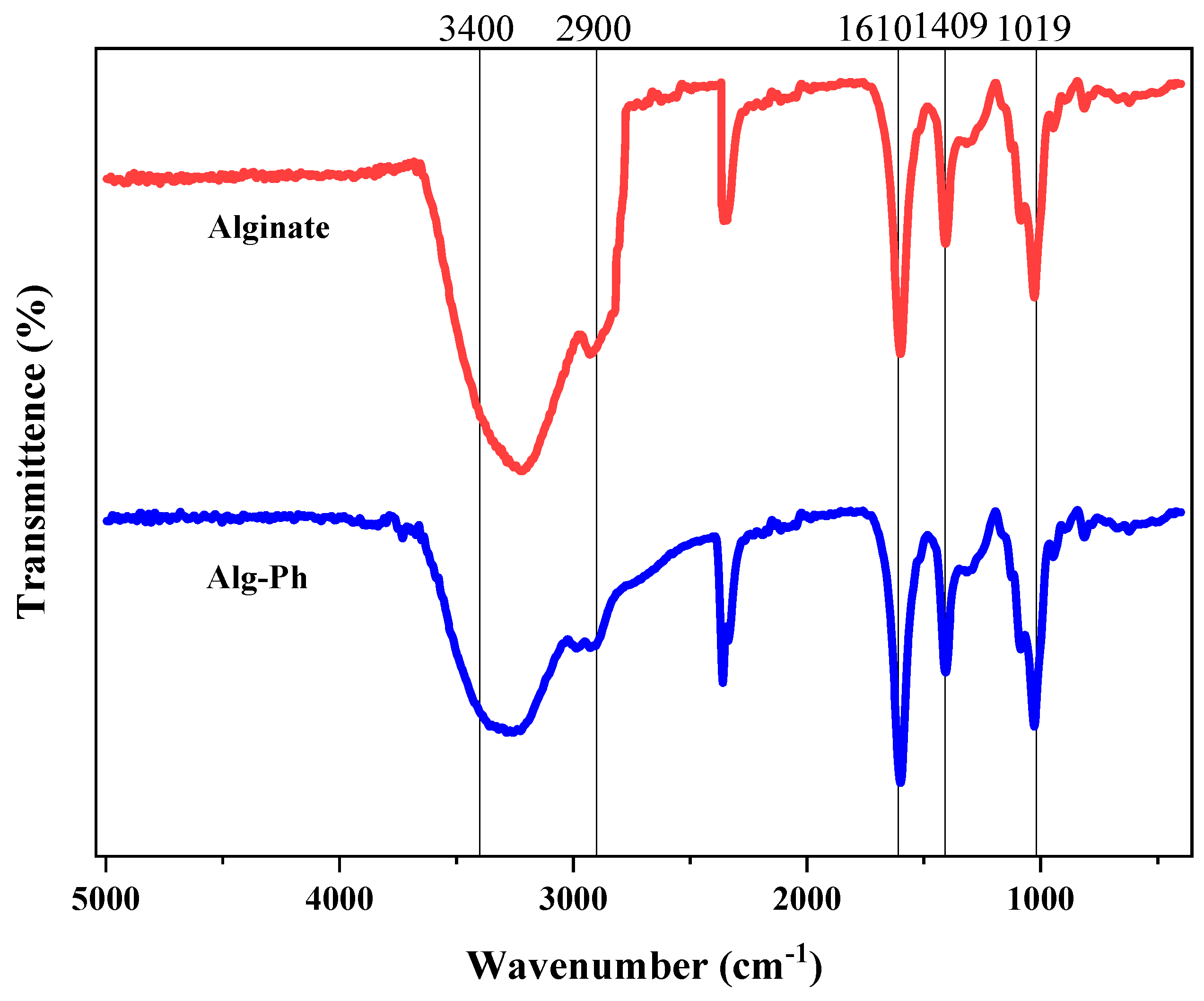

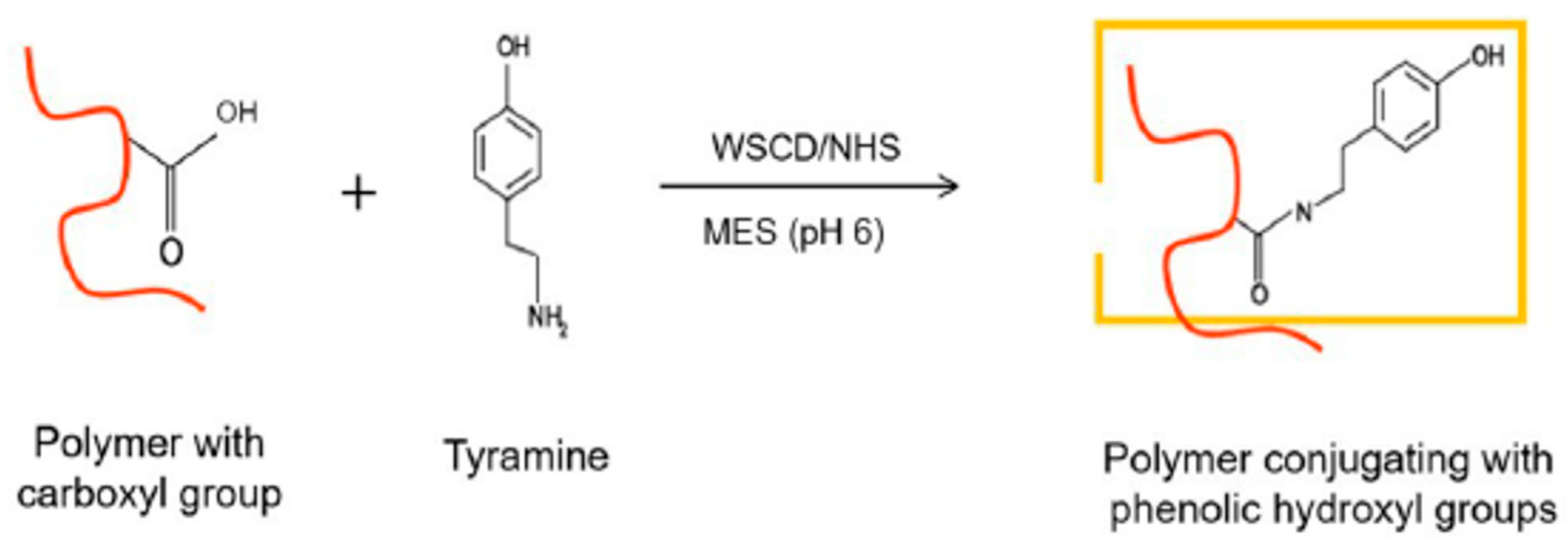

2.2. Fourier-Transform Spectroscopy of the Alginate-Derivative

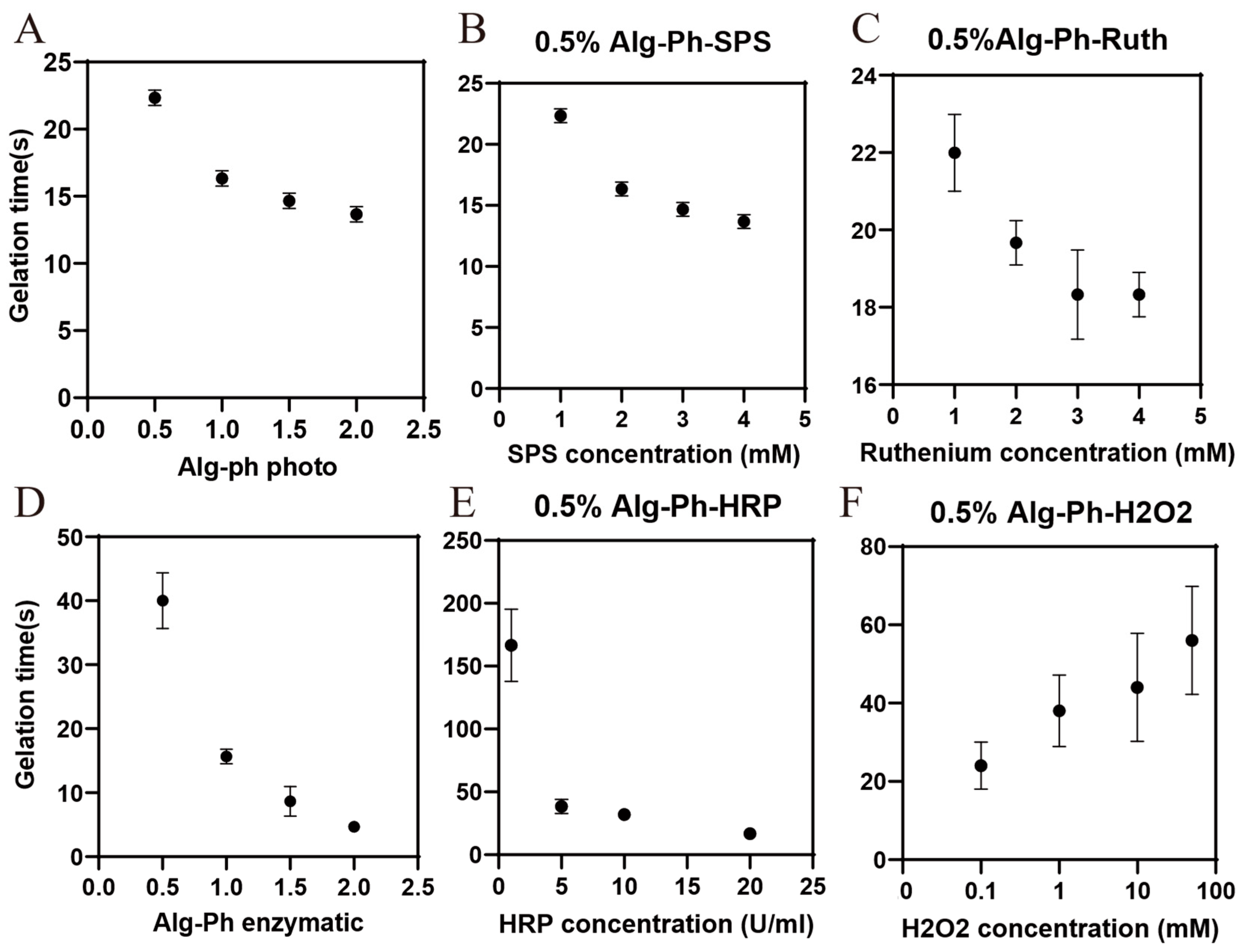

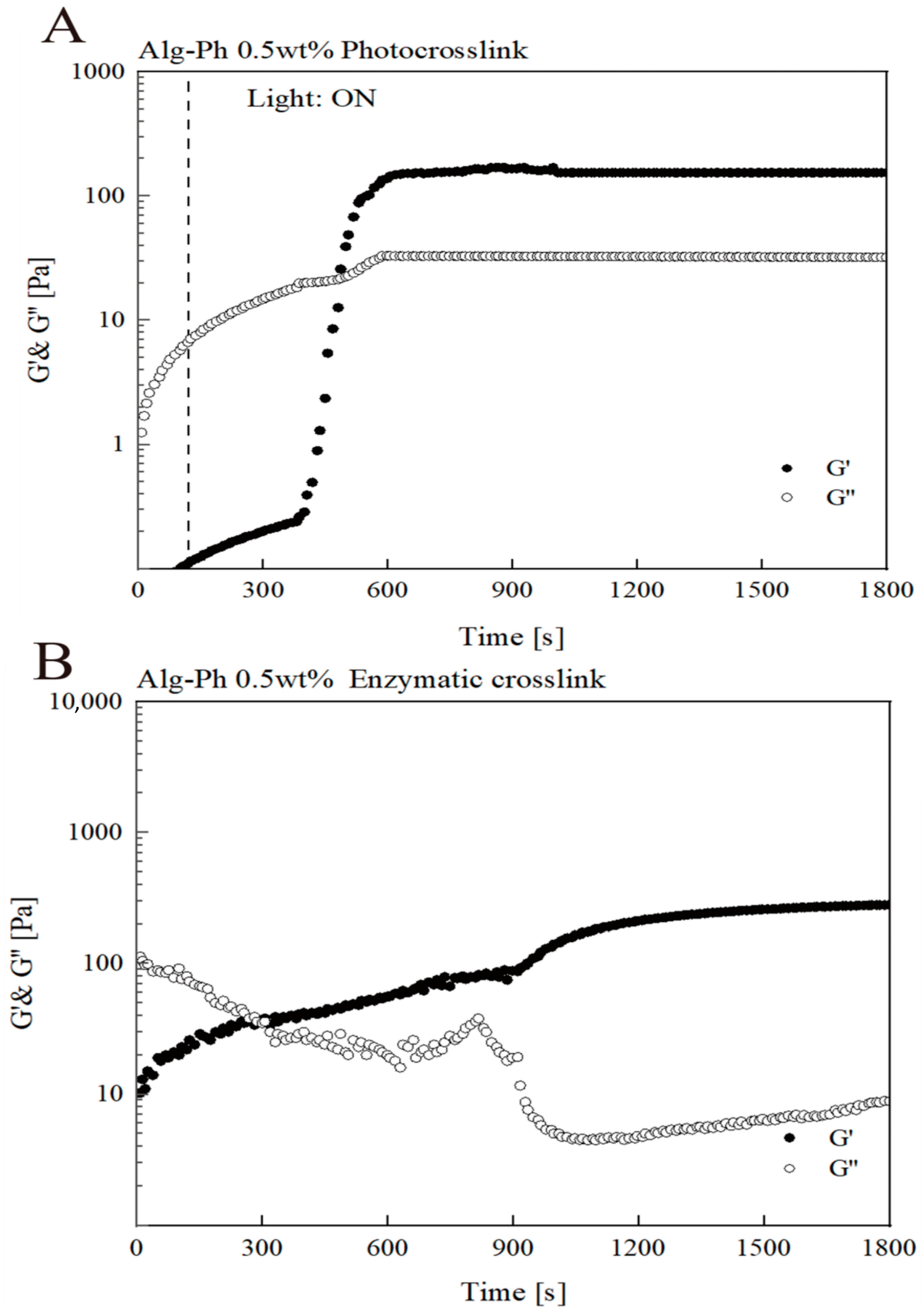

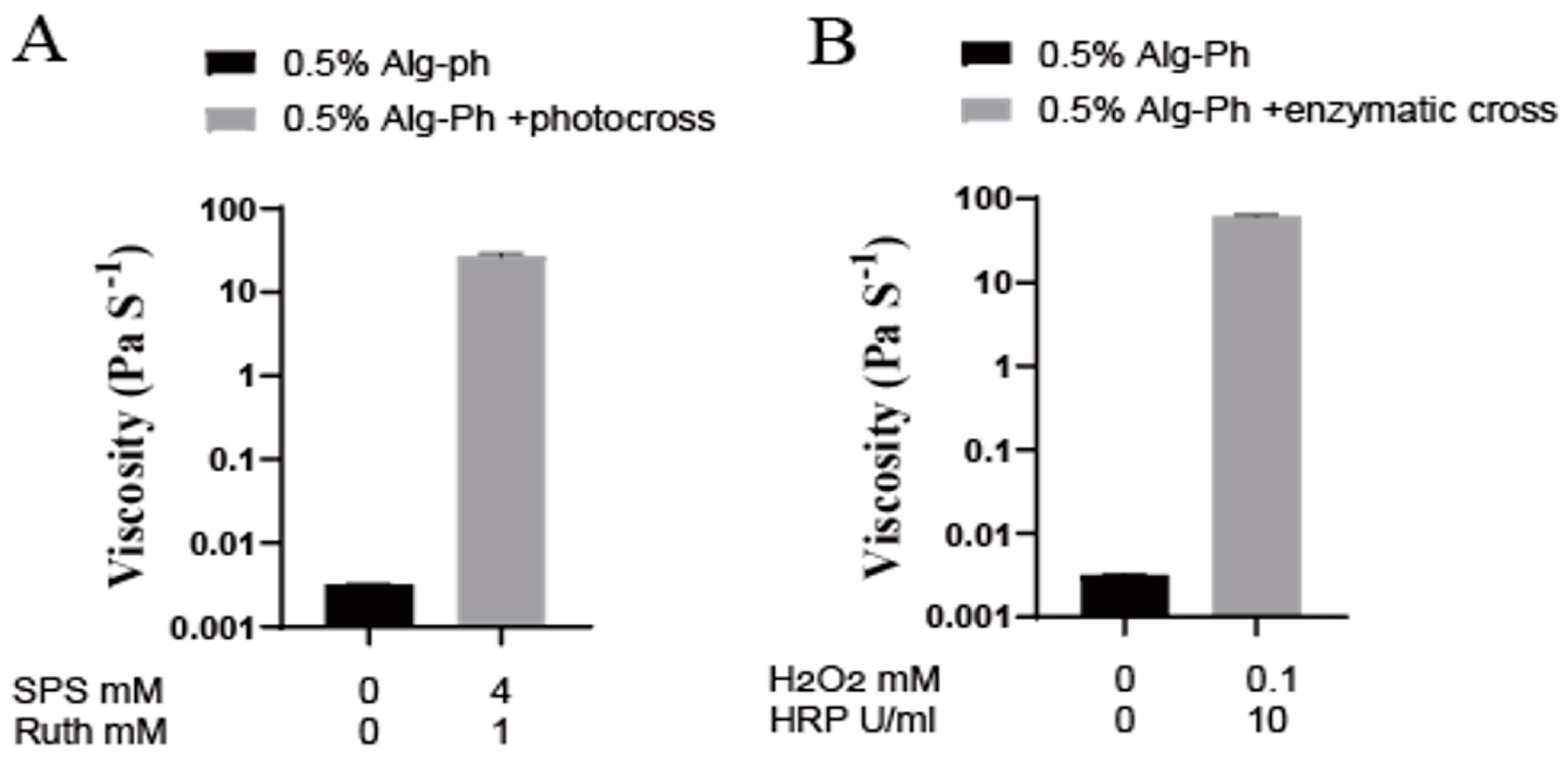

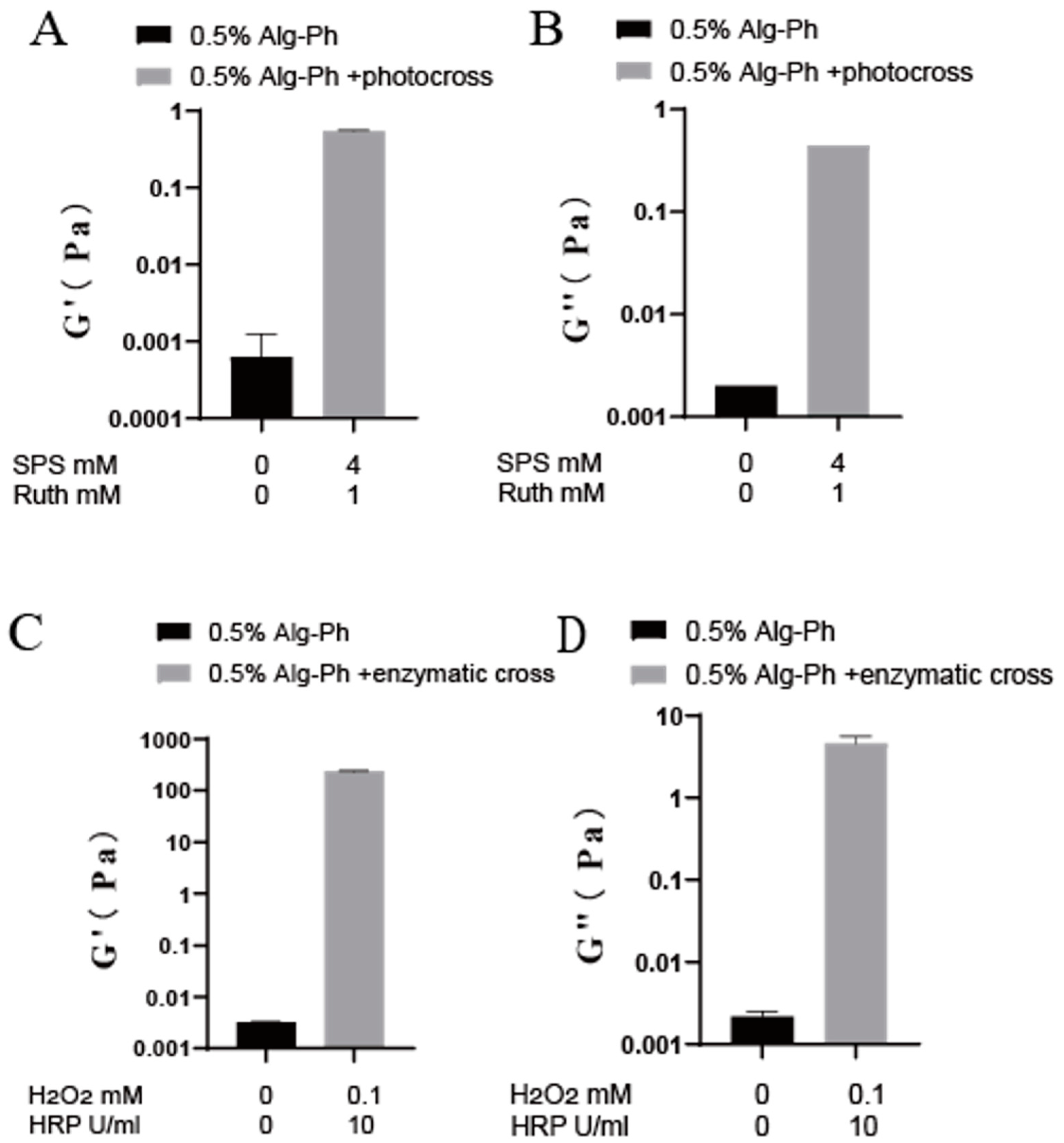

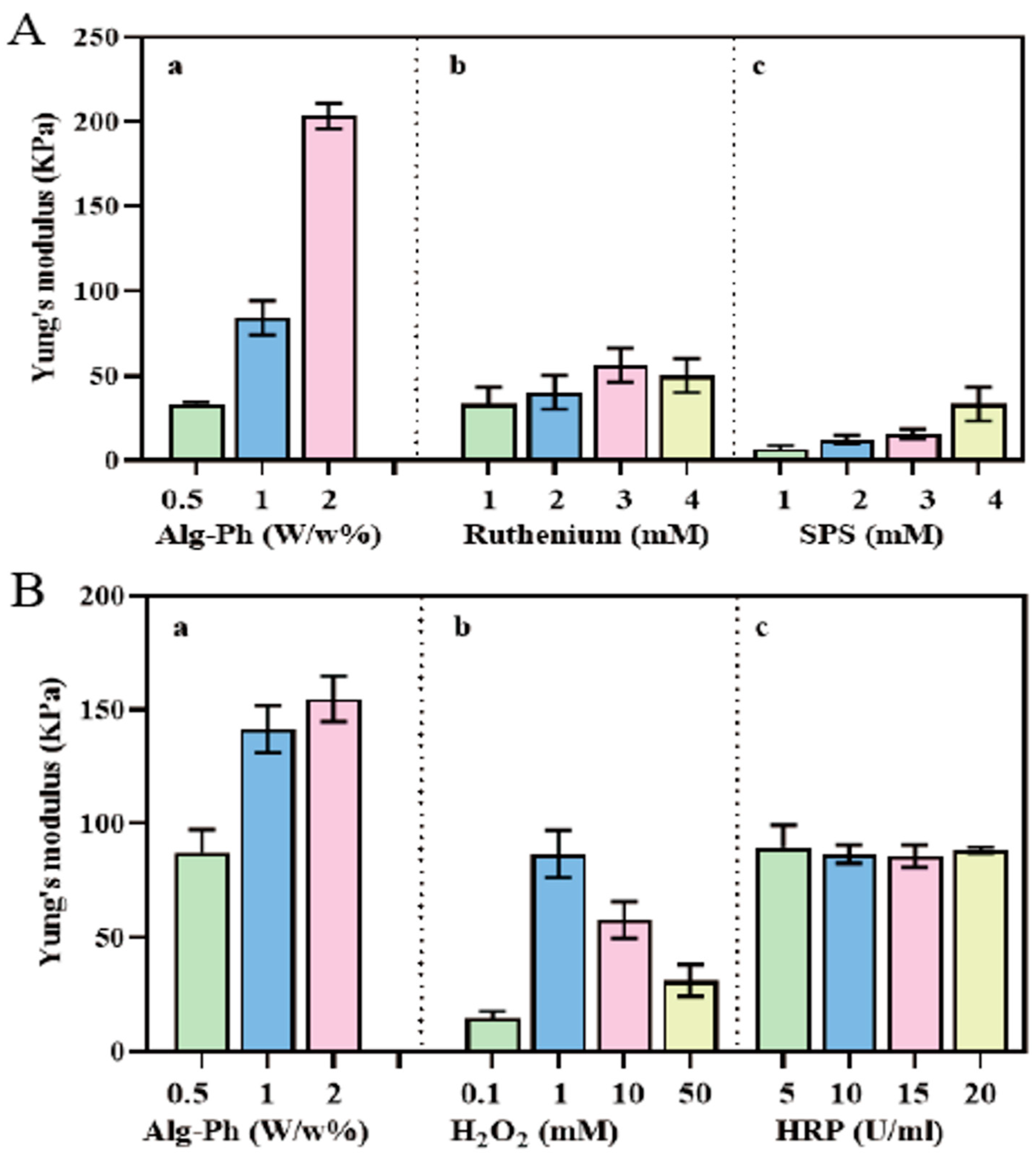

2.3. Gelation Process Optimization

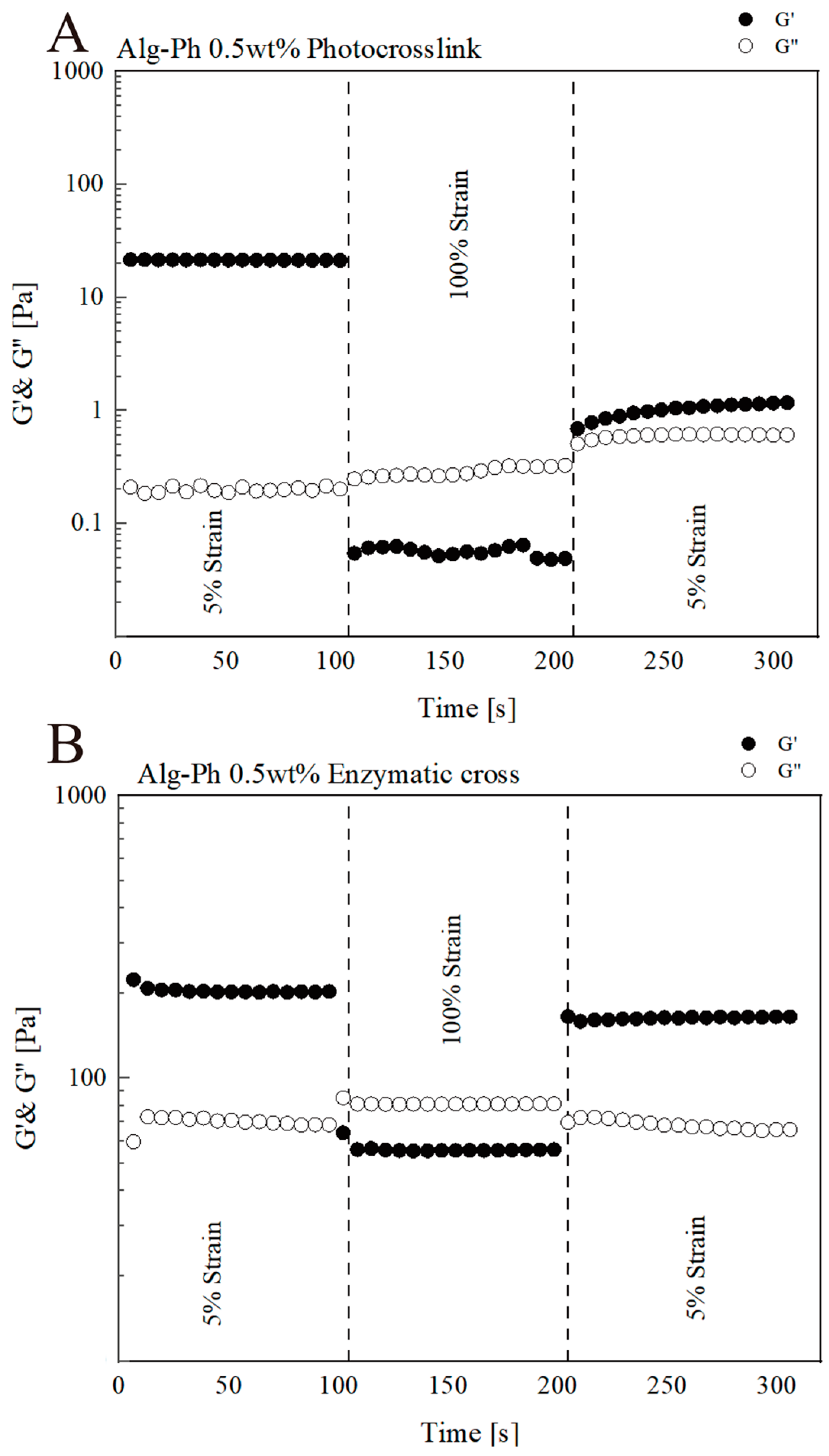

2.4. Analysis of Hydrogel Properties

2.5. Texture-Related Properties

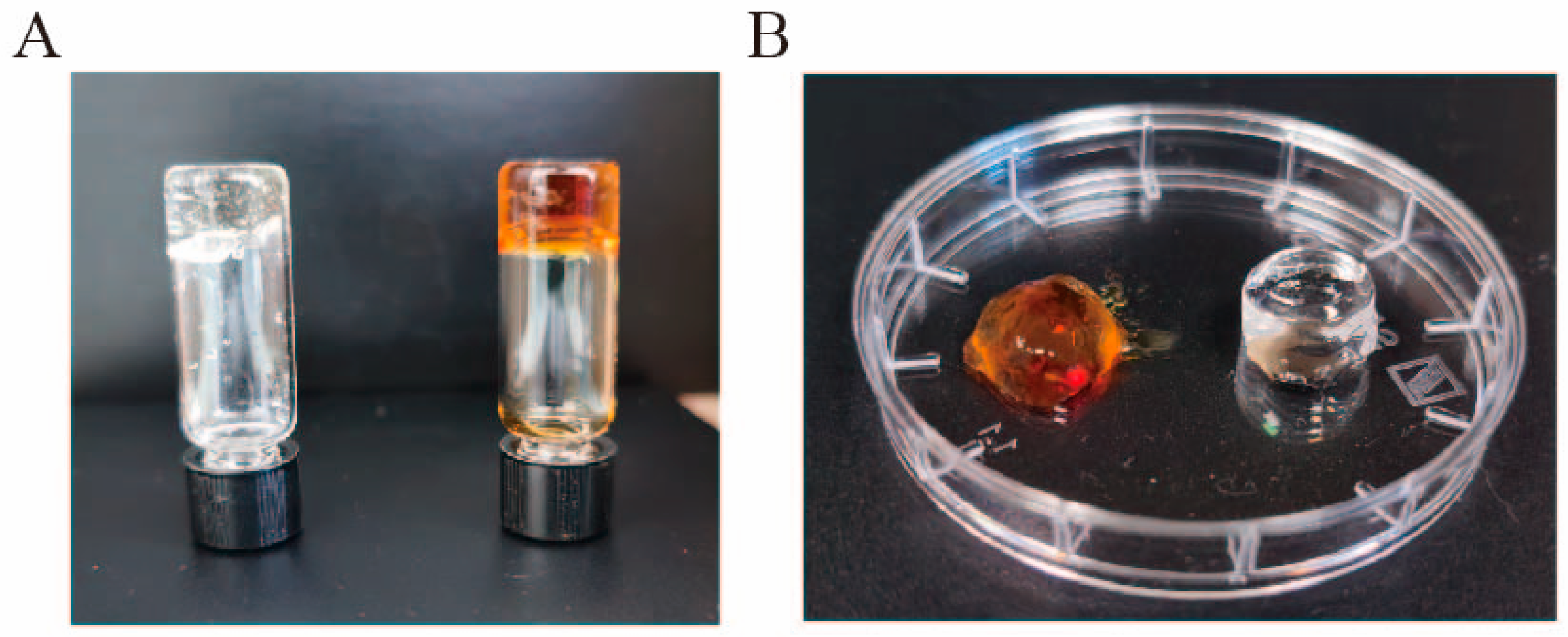

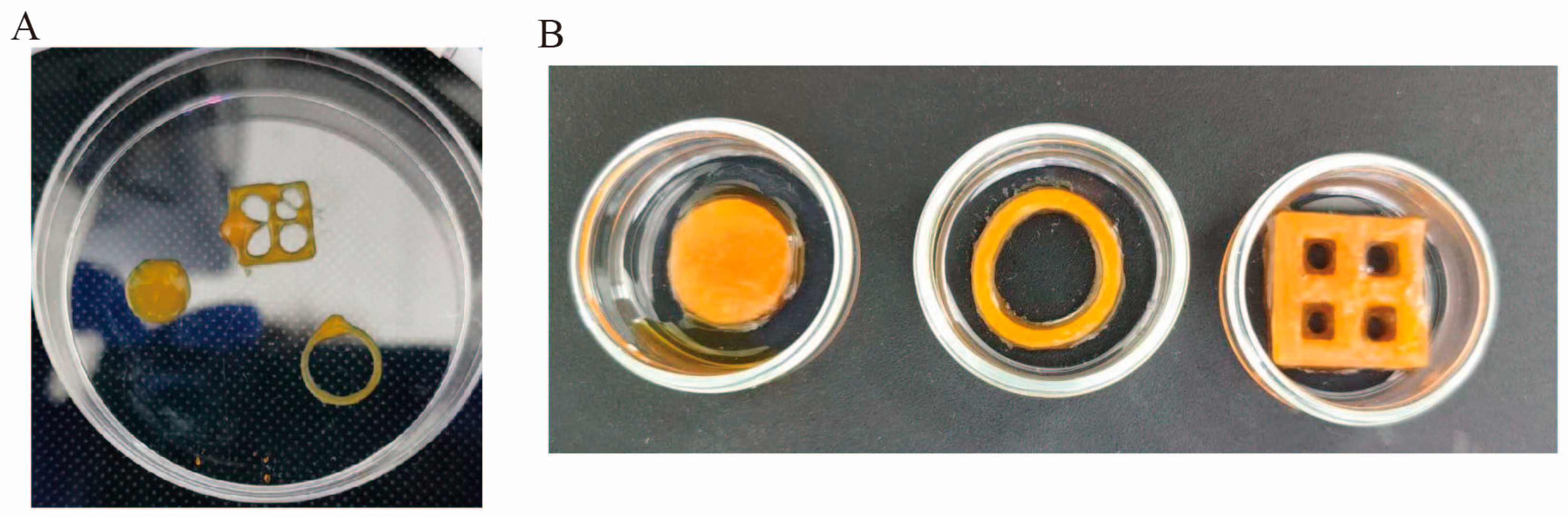

2.6. Printability Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Chemical Modification of Alginate

3.3. FTIR

3.4. Optimization of Crosslinking System

3.5. Rheology Analysis

3.6. Texture Analysis

4. Conclusions and Perspective

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HRP | Horseradish Peroxidase |

| Alg-Ph | Phenolized alginate |

| SPS | Sulfonated Polysulfone |

| Ruth | Ruthenium |

| EDC | 1-ethyl-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide |

| NHS | N-hydroxybutanediimide (EDC/NHS) |

| HA | Hyaluronic acid |

| GA | Gallic acid |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

References

- Abourehab, M.A.S.; Rajendran, R.R.; Singh, A.; Pramanik, S.; Shrivastav, P.; Ansari, M.J.; Manne, R.; Amaral, L.S.; Deepak, A. Alginate as a Promising Biopolymer in Drug Delivery and Wound Healing: A Review of the State-of-the-Art. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masoumi Shahrbabak, S.; Jalali, S.M.; Fathabadi, M.F.; Tayebi-Khorrami, V.; Amirinejad, M.; Forootan, S.; Saberifar, M.; Fadaei, M.R.; Najafi, Z.; Askari, V.R. Modified Alginates for Precision Drug Delivery: Advances in Controlled-Release and Targeting Systems. Int. J. Pharm. X 2025, 10, 100381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, N.H.; Chien, T.B.; Cuong, D.X. Polymer-Based Hydrogels Applied in Drug Delivery: An Overview. Gels 2023, 9, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Jiang, J.; Zhe, M.; Yu, P.; Xing, F.; Xiang, Z. Alginate-based 3D bioprinting strategies for structure–function integrated tissue regeneration. J. Mater. Chem. B 2025, 13, 12765–12811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groll, J.; Burdick, J.A.; Cho, D.-W.; Derby, B.; Gelinsky, M.; Heilshorn, S.C.; Jüngst, T.; Malda, J.; Mironov, V.A.; Nakayama, K.; et al. A Definition of Bioinks and Their Distinction from Biomaterial Inks. Biofabrication 2018, 11, 013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J.J.; Naudiyal, P.; Lim, K.S.; Poole-Warren, L.A.; Martens, P.J. A Comparative Study of Enzyme Initiators for Crosslinking Phenol-Functionalized Hydrogels for Cell Encapsulation. Biomater. Res. 2016, 20, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Fowler, E.W.; Jia, X. Chemical Synthesis of Biomimetic Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering. Polym. Int. 2017, 66, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifkovits, J.L.; Burdick, J.A. Review: Photopolymerizable and Degradable Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering Applications. Tissue Eng. 2007, 13, 2369–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastin, H.; Abousalman-Rezvani, Z. 3D bioprinting of alginate for cancer therapy: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 320, 145494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, S.; Kotani, T.; Harada, R.; Goto, R.; Morita, T.; Bouissil, S.; Dubessay, P.; Pierre, G.; Michaud, P.; El Boutachfaiti, R.; et al. Development of phenol-grafted polyglucuronic acid and its application to extrusion-based bioprinting inks. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 277, 118820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamrai, M.; Banerjee, S.L.; Paul, S.; Ghosh, A.K.; Sarkar, P.; Kundu, P.P. A Mussel Mimetic, Bioadhesive, Antimicrobial Patch Based on Dopamine-Modified Bacterial Cellulose/rGO/Ag NPs: A Green Approach toward Wound-Healing Applications. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 12083–12097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Cheng, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, L. Noncompressible Hemostasis and Bone Regeneration Induced by an Absorbable Bioadhesive Self-Healing Hydrogel. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2009189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, S.; Touahir, L.; Salvador Andresa, J.; Allongue, P.; Chazalviel, J.-N.; Gouget-Laemmel, A.C.; Henry De Villeneuve, C.; Moraillon, A.; Ozanam, F.; Gabouze, N.; et al. Semiquantitative Study of the EDC/NHS Activation of Acid Terminal Groups at Modified Porous Silicon Surfaces. Langmuir 2010, 26, 809–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yan, Q.; Liu, H.-B.; Zhou, X.-H.; Xiao, S.-J. Different EDC/NHS Activation Mechanisms between PAA and PMAA Brushes and the Following Amidation Reactions. Langmuir 2011, 27, 12058–12068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Wei, Z.; Xu, X.; Feng, Q.; Xu, J.; Bian, L. Efficient Catechol Functionalization of Biopolymeric Hydrogels for Effective Multiscale Bioadhesion. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 103, 109835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, R.; Nakahata, M.; Sakai, S. Phenol-Grafted Alginate Sulfate Hydrogel as an Injectable FGF-2 Carrier. Gels 2022, 8, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, G.; Marcinek, P.; Sulzinger, N.; Schieberle, P.; Krautwurst, D. Food Sources and Biomolecular Targets of Tyramine. Nutr. Rev. 2019, 77, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, V.G.; Burdick, J.A. Chemically Modified Biopolymers for the Formation of Biomedical Hydrogels. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 10908–10949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.W.; Choi, J.H.; Lee, Y.; Park, K.D. Horseradish Peroxidase-Catalysed in Situ-Forming Hydrogels for Tissue-Engineering Applications: HRP-Catalysed in Situ Forming Hydrogels. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2015, 9, 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian, M.; Khoshfetrat, A.B.; Khatami, N.; Morshedloo, F.; Rahbarghazi, R.; Hassani, A.; Kiani, S. Influence of Gelatin and Collagen Incorporation on Peroxidase-Mediated Injectable Pectin-Based Hydrogel and Bioactivity of Fibroblasts. J. Biomater. Appl. 2021, 36, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, S.; Kawakami, K. Synthesis and Characterization of Both Ionically and Enzymatically Cross-Linkable Alginate. Acta Biomater. 2007, 3, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurisawa, M.; Chung, J.E.; Yang, Y.Y.; Gao, S.J.; Uyama, H. Injectable Biodegradable Hydrogels Composed of Hyaluronic Acid–Tyramine Conjugates for Drug Delivery and Tissue Engineering. Chem. Commun. 2005, 34, 4312–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghati, S.; Rahbarghazi, R.; Baradar Khoshfetrat, A.; Moharamzadeh, K.; Tayefi Nasrabadi, H.; Roshangar, L. Phenolated Alginate-Collagen Hydrogel Induced Chondrogenic Capacity of Human Amniotic Mesenchymal Stem Cells. J. Biomater. Appl. 2021, 36, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Soliman, B.G.; Alcala-Orozco, C.R.; Li, J.; Vis, M.A.M.; Santos, M.; Wise, S.G.; Levato, R.; Malda, J.; Woodfield, T.B.F.; et al. Rapid Photocrosslinking of Silk Hydrogels with High Cell Density and Enhanced Shape Fidelity. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2020, 9, 1901667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRosa, M. Photosensitized Singlet Oxygen and Its Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002, 233–234, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uman, S.; Dhand, A.; Burdick, J.A. Recent Advances in Shear-thinning and Self-healing Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 48668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Richards, D.J.; Pollard, S.; Tan, Y.; Rodriguez, J.; Visconti, R.P.; Trusk, T.C.; Yost, M.J.; Yao, H.; Markwald, R.R.; et al. Engineering Alginate as Bioink for Bioprinting. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 4323–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colosi, C.; Shin, S.R.; Manoharan, V.; Massa, S.; Costantini, M.; Barbetta, A.; Dokmeci, M.R.; Dentini, M.; Khademhosseini, A. Microfluidic Bioprinting of Heterogeneous 3D Tissue Constructs Using Low-Viscosity Bioink. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, K.S.; Klotz, B.J.; Lindberg, G.C.J.; Melchels, F.P.W.; Hooper, G.J.; Malda, J.; Gawlitta, D.; Woodfield, T.B.F. Visible Light Cross-Linking of Gelatin Hydrogels Offers an Enhanced Cell Microenvironment with Improved Light Penetration Depth. Macromol. Biosci. 2019, 19, 1900098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, K.S.; Schon, B.S.; Mekhileri, N.V.; Brown, G.C.J.; Chia, C.M.; Prabakar, S.; Hooper, G.J.; Woodfield, T.B.F. New Visible-Light Photoinitiating System for Improved Print Fidelity in Gelatin-Based Bioinks. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2, 1752–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fancy, D.A.; Denison, C.; Kim, K.; Xie, Y.; Holdeman, T.; Amini, F.; Kodadek, T. Scope, Limitations and Mechanistic Aspects of the Photo-Induced Cross-Linking of Proteins by Water-Soluble Metal Complexes. Chem. Biol. 2000, 7, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvin, C.M.; Danon, S.J.; Brownlee, A.G.; White, J.F.; Hickey, M.; Liyou, N.E.; Edwards, G.A.; Ramshaw, J.A.M.; Werkmeister, J.A. Evaluation of Photo-crosslinked Fibrinogen as a Rapid and Strong Tissue Adhesive. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2010, 93A, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, C.; Saini, A.; Maji, P.K. Energy Efficient Facile Extraction Process of Cellulose Nanofibres and Their Dimensional Characterization Using Light Scattering Techniques. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 165, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhim, J.-W.; Reddy, J.P.; Luo, X. Isolation of Cellulose Nanocrystals from Onion Skin and Their Utilization for the Preparation of Agar-Based Bio-Nanocomposites Films. Cellulose 2015, 22, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemdar, A.; Sain, M. Isolation and Characterization of Nanofibers from Agricultural Residues—Wheat Straw and Soy Hulls. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 1664–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadzadeh, S.; Desobry, S.; Keramat, J.; Nasirpour, A. Crystalline Structure and Morphological Properties of Porous Cellulose/Clay Composites: The Effect of Water and Ethanol as Coagulants. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 141, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, S.M.L.; Rehman, N.; De Miranda, M.I.G.; Nachtigall, S.M.B.; Bica, C.I.D. Chlorine-Free Extraction of Cellulose from Rice Husk and Whisker Isolation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 87, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, D.; Yu, K.; Cao, W.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, H.; Sun, Z.; Guo, C.; et al. White-Light Crosslinkable Milk Protein Bioadhesive with Ultrafast Gelation for First-Aid Wound Treatment. Biomater. Res. 2023, 27, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasenauer, A.; Bevc, K.; McCabe, M.C.; Chansoria, P.; Saviola, A.J.; Hansen, K.C.; Christman, K.L.; Zenobi-Wong, M. Volumetric Printed Biomimetic Scaffolds Support in Vitro Lactation of Human Milk-Derived Mammary Epithelial Cells. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadu5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.-N.; Li, J.; Ni, K.; Han, C.Y.; Shen, H.L.; Zhao, L.L.; Li, Z.Z. Preparation of Photo-Crosslinking Carboxymethyl Chitosan Hydrogel for Sustained Drug Release. Mater. Eng. 2020, 48, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.T.; West, J.L. Photopolymerizable Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering Applications. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 4307–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun Han Chang, R.; Lee, J.C.-W.; Pedron, S.; Harley, B.A.C.; Rogers, S.A. Rheological Analysis of the Gelation Kinetics of an Enzyme Cross-Linked PEG Hydrogel. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 2198–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xiong, X.; Liu, X.; Cui, R.; Wang, C.; Zhao, G.; Zhi, W.; Lu, M.; Duan, K.; Weng, J.; et al. 3D Bioprinting of Shear-Thinning Hybrid Bioinks with Excellent Bioactivity Derived from Gellan/Alginate and Thixotropic Magnesium Phosphate-Based Gels. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 5500–5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Hu, S.; Zhang, S.; Dong, S.; Hu, J.; Kang, L.; Yang, X. A Double-Layer Hydrogel Based on Alginate-Carboxymethyl Cellulose and Synthetic Polymer as Sustained Drug Delivery System. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vennat, B.; Lardy, F.; Arvouet-Grand, A.; Pourrat, A. Comparative Texturometric Analysis of Hydrogels Based on Cellulose Derivatives, Carraghenates, and Alginates: Evaluation of Adhesiveness. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 1998, 24, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delanne-Cuménal, A.; Lainé, E.; Hoffart, V.; Verney, V.; Garrait, G.; Beyssac, E. Effect of Molecules’ Physicochemical Properties on Whey Protein/Alginate Hydrogel Rheology, Microstructure and Release Profile. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, H.H.; Whitney, J.E.; Szczesniak, A.S. The Texturometer—A New Instrument for Objective Texture Measurement. J. Food Sci. 1963, 28, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, U.; Ali, Z.; Nazir, M.S.; Ul Hassan, S.; Rafiq, S.; Jamil, F.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.H.; Ali, M.; Khan Niazi, M.B.; Ahmad, N.M.; et al. Isolation of Cellulose from Wheat Straw Using Alkaline Hydrogen Peroxide and Acidified Sodium Chlorite Treatments: Comparison of Yield and Properties. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2020, 2020, 9765950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghati, S.; Khoshfetrat, A.B.; Tayefi Nasrabadi, H.; Roshangar, L.; Rahbarghazi, R. Fabrication of Alginate-Based Hydrogel Cross-Linked via Horseradish Peroxidase for Articular Cartilage Engineering. BMC Res. Notes 2021, 14, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-J.; Chu, Y.-Z.; Chen, C.-K.; Liao, Y.-S.; Yeh, M.-Y. Preparation of Conductive Self-Healing Hydrogels via an Interpenetrating Polymer Network Method. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 6620–6627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Yoon, J.; Ahn, K.H.; Choi, S.-H.; Char, K. Injectable Hydrogels with Improved Mechanical Property Based on Electrostatic Associations. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2021, 299, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meicenheimer, R.D.; Niklas, K.J. Plant Biomechanics: An Engineering Approach to Plant Form and Function. Int. J. Plant Sci. 1993, 154, 364–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, F.; Lainé, E.; Lukova, P.; Katsarov, P.; Delattre, C. Tailoring the Properties of Marine-Based Alginate Hydrogels: A Comparison of Enzymatic (HRP) and Visible-Light (SPS/Ruth)-Induced Gelation. Mar. Drugs 2026, 24, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010022

Wang F, Lainé E, Lukova P, Katsarov P, Delattre C. Tailoring the Properties of Marine-Based Alginate Hydrogels: A Comparison of Enzymatic (HRP) and Visible-Light (SPS/Ruth)-Induced Gelation. Marine Drugs. 2026; 24(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Feiyang, Emmanuelle Lainé, Paolina Lukova, Plamen Katsarov, and Cédric Delattre. 2026. "Tailoring the Properties of Marine-Based Alginate Hydrogels: A Comparison of Enzymatic (HRP) and Visible-Light (SPS/Ruth)-Induced Gelation" Marine Drugs 24, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010022

APA StyleWang, F., Lainé, E., Lukova, P., Katsarov, P., & Delattre, C. (2026). Tailoring the Properties of Marine-Based Alginate Hydrogels: A Comparison of Enzymatic (HRP) and Visible-Light (SPS/Ruth)-Induced Gelation. Marine Drugs, 24(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010022