Onnamides A and B Suppress Hepatitis B Virus Transcription by Inhibiting Viral Promoter Activity

Abstract

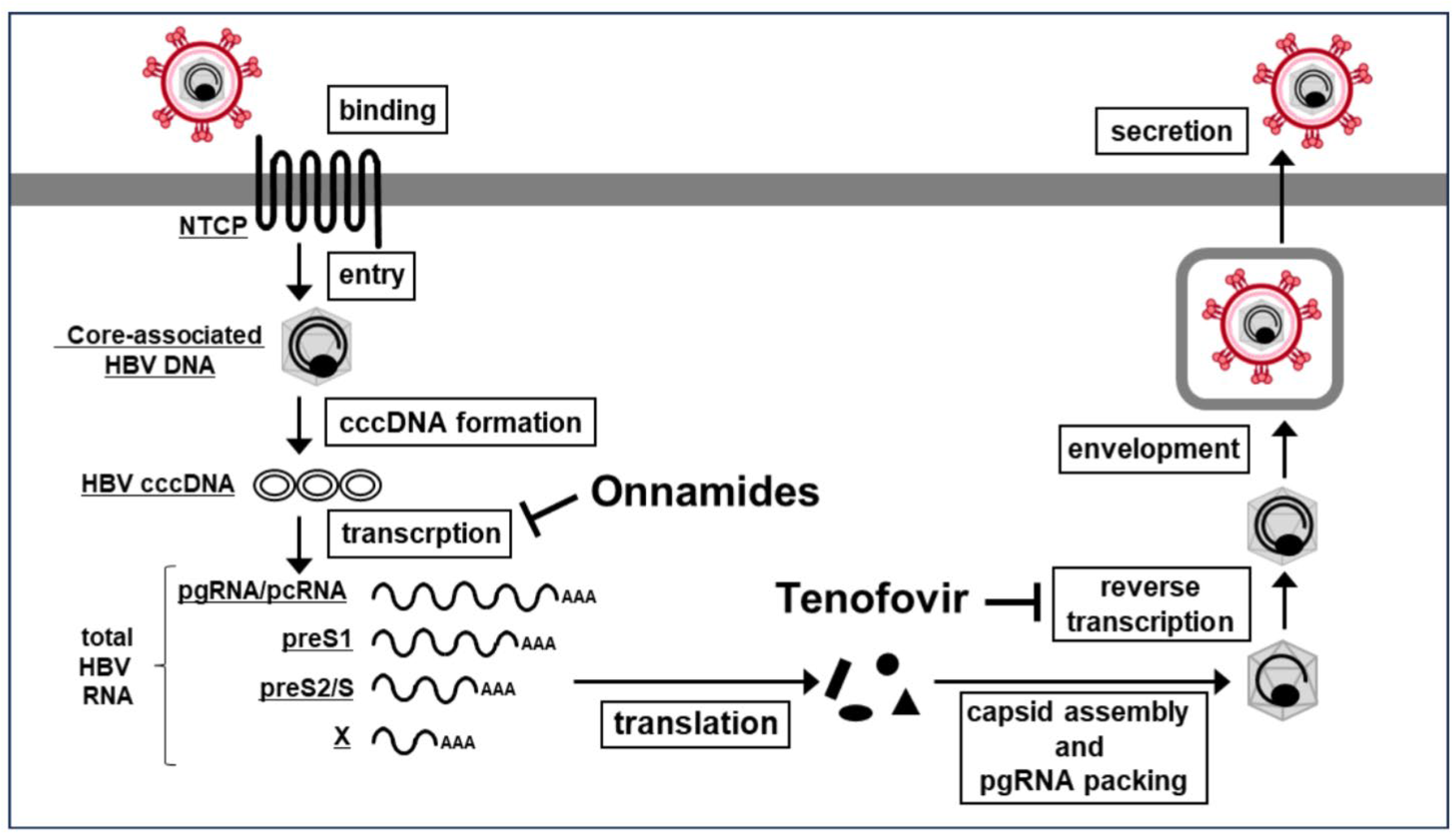

1. Introduction

2. Results

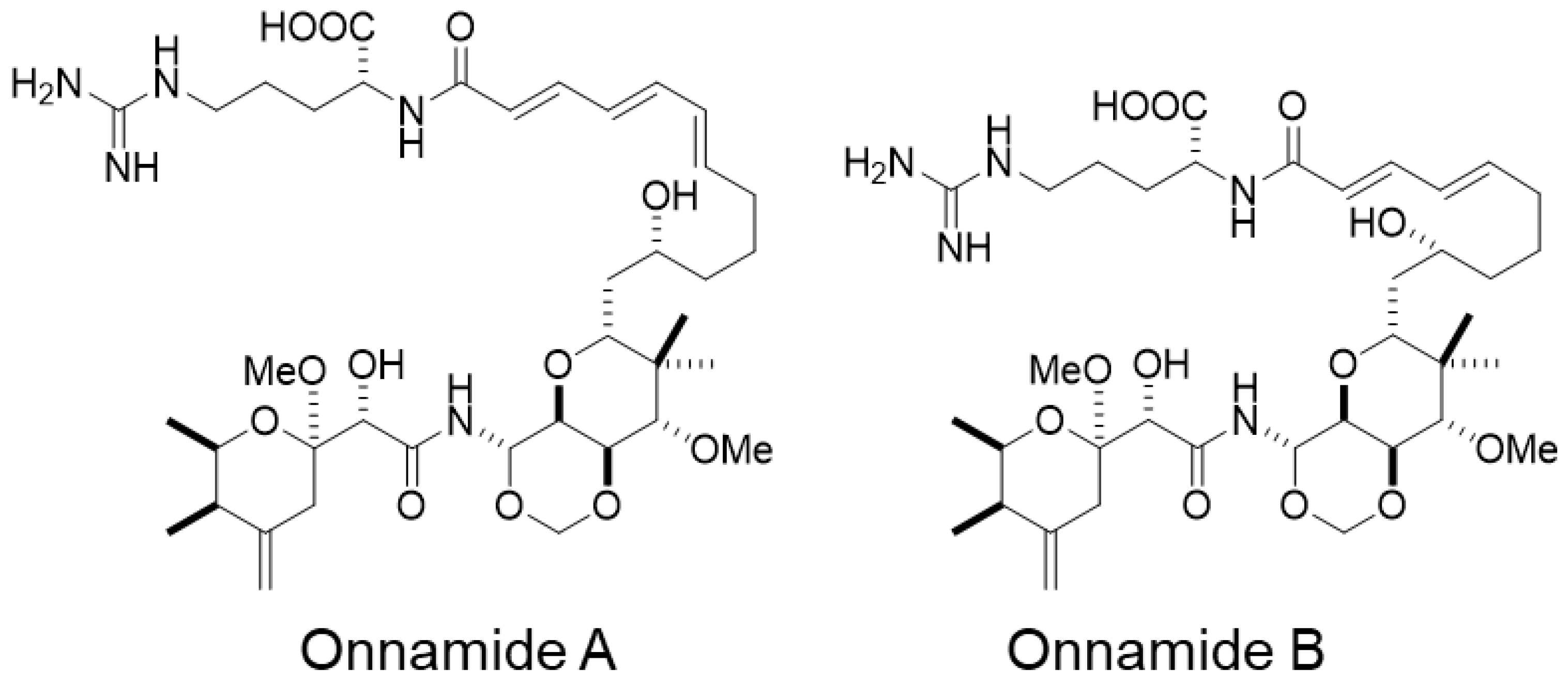

2.1. Onnamides A and B, Marine-Derived Natural Compounds Isolated from the Sponge Theonella sp.

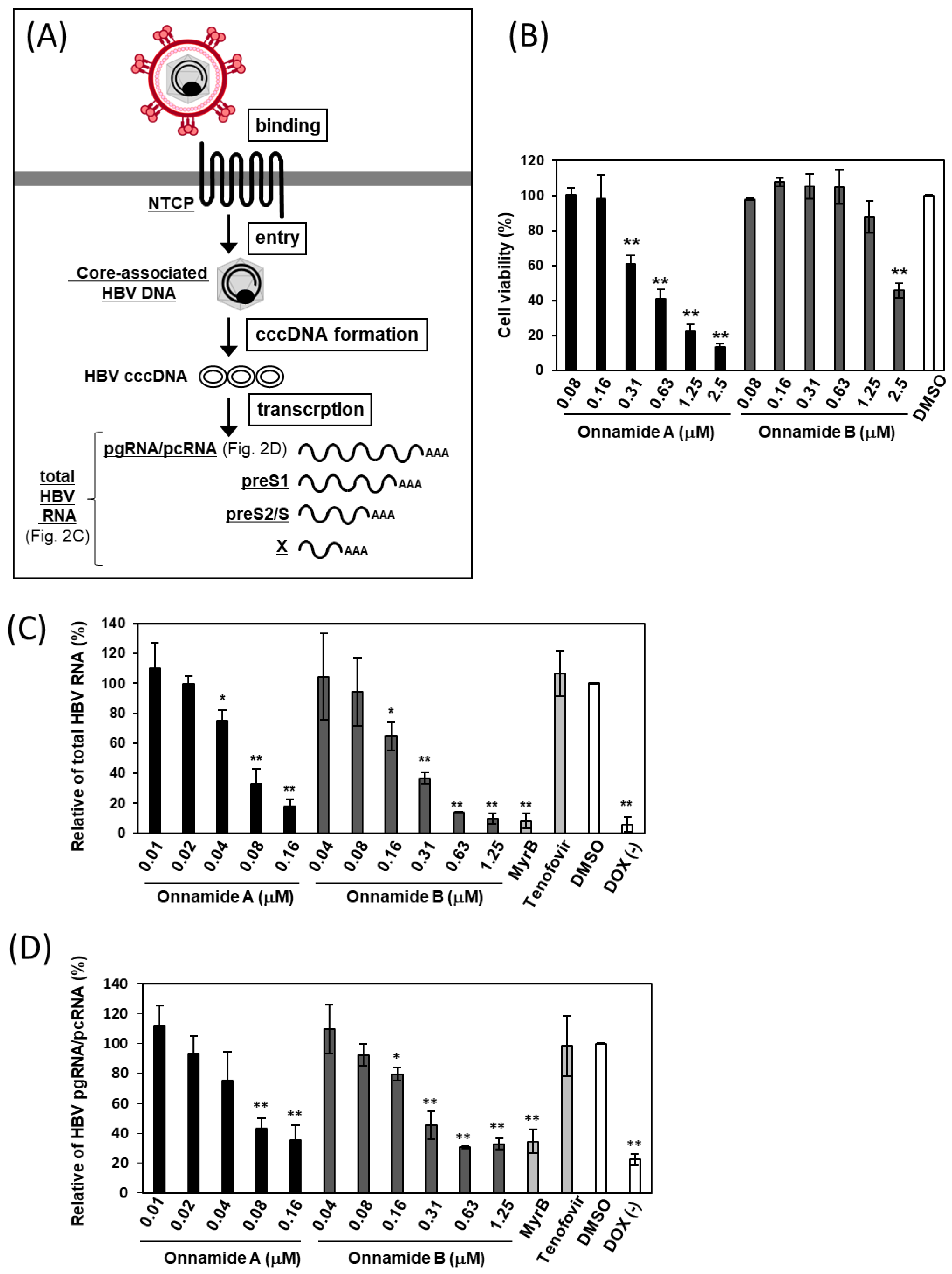

2.2. Onnamides A and B Suppress the Levels of Total HBV RNA and pgRNA/pcRNA

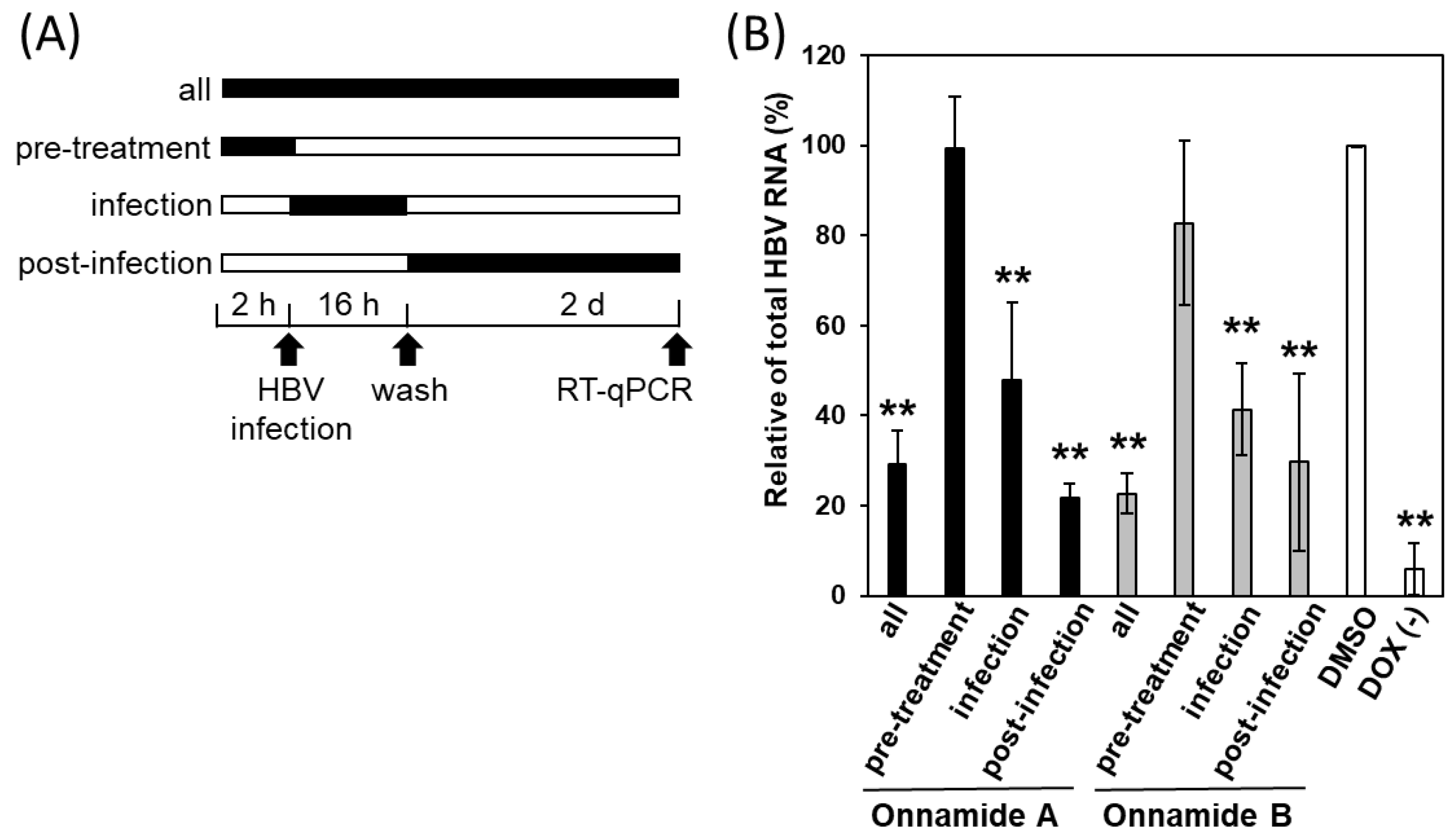

2.3. Onnamides A and B Most Effectively Suppress HBV at a Post-Entry Stage of the Viral Life Cycle

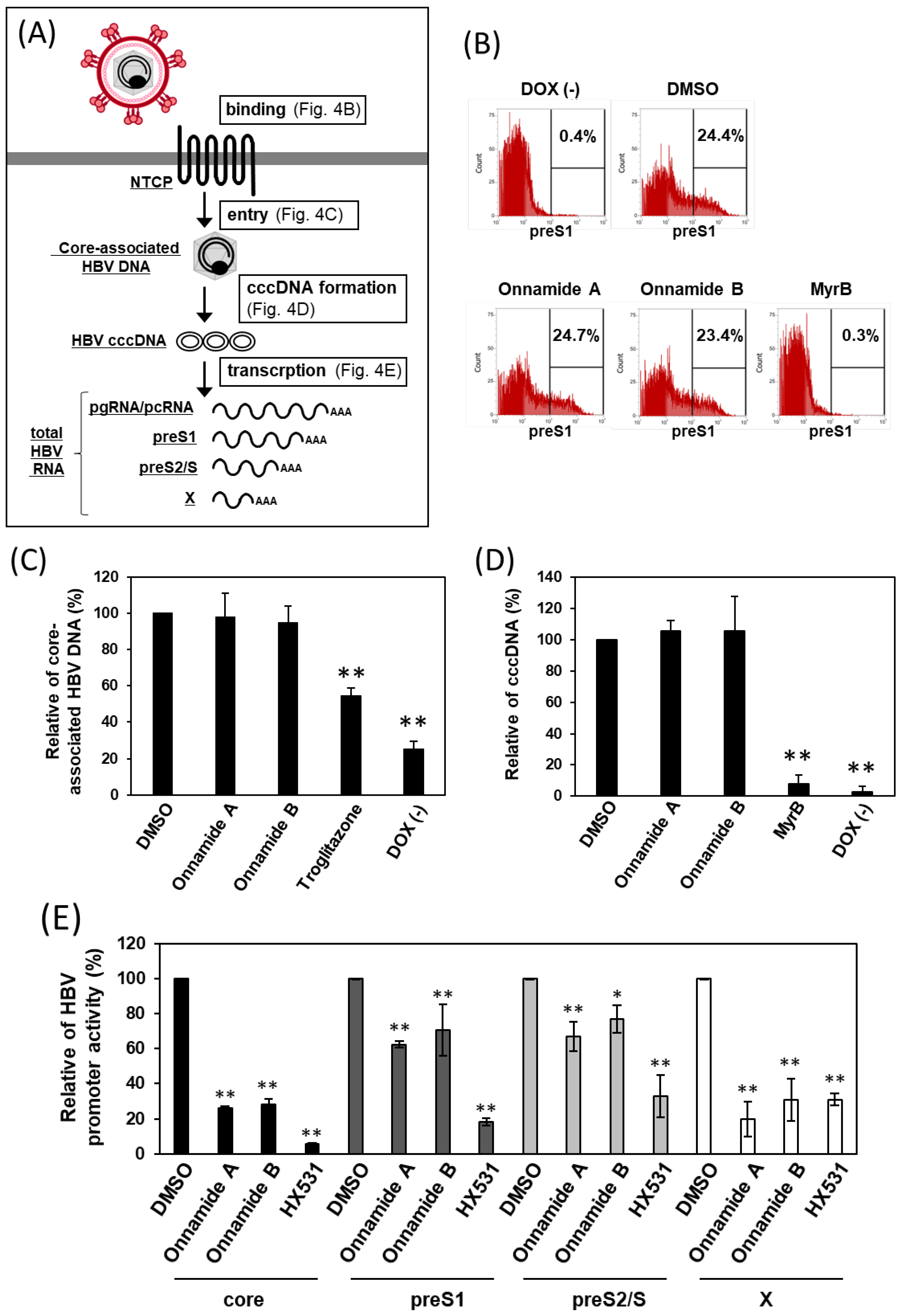

2.4. Onnamides A and B Suppress HBV RNA Transcription

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Specimens, Extraction, and Isolation of Onnamides A and B

4.2. Cells and HBV Preparation

4.3. Cytotoxicity Assay

4.4. Quantification of Total HBV RNA and pgRNA/pcRNA by RT-qPCR

4.5. Time-of-Addition Assay

4.6. preS1 Binding Assay

4.7. Quantification of Core-Associated HBV DNA by RT-qPCR

4.8. Quantification of HBV cccDNA by RT-qPCR

4.9. HBV Promoter Activity Measurement Using Dual-Luciferase Reporter System

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| cccDNA | covalently closed circular DNA |

| DMSO | dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DOX | doxycycline |

| FBS | fetal bovine serum |

| GEq | genome equivalents |

| HBV | hepatitis B virus |

| iNTCP | HBV-susceptible HepG2 cells with a doxycycline-inducible NTCP gene |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MyrB | Myrcludex B |

| NTCP | the sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

| pcRNA | precore mRNA |

| PEG8000 | polyethylene glycol 8000 |

| pgRNA | pregenomic RNA |

| preS1-TAMRA | C-terminally 5-carboxytetramethylrhodamine-conjugated and N-terminally myristoylated preS1 peptides corresponding to amino acids 2–48 |

| SI | selectivity index |

References

- World Health Organization. Hepatitis B. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Lou, L. Advances in nucleotide antiviral development from scientific discovery to clinical applications: Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for hepatitis B. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2013, 1, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonstra, A.; Sari, G. HBV cccDNA: The Molecular Reservoir of Hepatitis B Persistence and Challenges to Achieve Viral Eradication. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Zhong, G.; Xu, G.; He, W.; Jing, Z.; Gao, Z.; Huang, Y.; Qi, Y.; Peng, B.; Wang, H.; et al. Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide is a functional receptor for human hepatitis B and D virus. eLife 2012, 1, e00049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Pan, L.; Li, W. New Insights on Hepatitis B Virus Viral Transcription in Single Hepatocytes. Viruses 2024, 16, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raney, A.K.; Johnson, J.L.; Palmer, C.N.; McLachlan, A. Members of the nuclear receptor superfamily regulate transcription from the hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid promoter. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 1058–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watashi, K.; Liang, G.; Iwamoto, M.; Marusawa, H.; Uchida, N.; Daito, T.; Kitamura, K.; Muramatsu, M.; Ohashi, H.; Kiyohara, T.; et al. Interleukin-1 and Tumor Necrosis Factor-α trigger restriction of hepatitis B virus infection via a cytidine deaminase activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID). J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 31715–31727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahluwalia, S.; Choudhary, D.; Tyagi, P.; Kumar, V.; Vivekanandan, P. Vitamin D signaling inhibits HBV activity by directly targeting the HBV core promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 101233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.K.; Abdelhafez, T.H.; Takeuchi, J.S.; Wakae, K.; Sugiyama, M.; Tsuge, M.; Ito, M.; Watashi, K.; El Kassas, M.; Kato, T.; et al. MafF is an antiviral host factor that suppresses transcription from hepatitis B virus core promoter. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e00767-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.R.; Copp, B.R.; Grkovic, T.; Keyzers, R.A.; Prinsep, M.R. Marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2024, 41, 162–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Van Wagoner, R.M.; Harper, M.K.; Baker, H.L.; Hooper, J.N.A.; Bewley, C.A.; Ireland, C.M. Mirabamides E–H, HIV-Inhibitory Depsipeptides from the Sponge Stelletta clavosa. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-H.; Hsieh, C.-Y.; Chiou, C.-T.; Caro, E.J.G.V.; Tayo, L.L.; Tsai, P.-W. In Vitro and In Silico Studies on the Anti-H1N1 Activity of Bioactive Compounds from Marine-Derived Streptomyces ardesiacus. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surti, M.; Patel, M.; Adnan, M.; Moin, A.; Ashraf, S.A.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Snoussi, M.; Deshpande, S.; Reddy, M.N. Ilimaquinone (marine sponge metabolite) as a novel inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 key target proteins in comparison with suggested COVID-19 drugs: Designing, docking and molecular dynamics simulation study. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 37707–37720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakemi, S.; Ichiba, T.; Kohmoto, S.; Saucy, G.; Higa, T. Isolation and structure elucidation of onnamide A, a new bioactive metabolite of a marine sponge, Theonella sp. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 4851–4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burres, N.S.; Clement, J.J. Antitumor activity and mechanism of action of the novel marine natural products mycalamide-A and -B and onnamide. Cancer Res. 1989, 49, 2935–2940. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.-H.; Nishimura, S.; Matsunaga, S.; Fusetani, N.; Horinouchi, S.; Yoshida, M. Inhibition of protein synthesis and activation of stress-activated protein kinases by onnamide A and theopederin B, antitumor marine natural products. Cancer Sci. 2005, 96, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, Y.; Higa, N.; Yoshida, T.; Tyas, T.A.; Mori-Yasumoto, K.; Yasumoto-Hirose, M.; Tani, H.; Tanaka, J.; Jomori, T. Onnamide A suppresses the severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus 2 infection without inhibiting 3-chymotrypsin-like cysteine protease. J. Biochem. 2024, 176, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomori, T.; Higa, N.; Tyas, T.A.; Matsuura, N.; Ueda, Y.; Suetake, A.; Miyazaki, S.; Watanabe, S.; Arizono, S.; Hayashi, Y.; et al. Onnamides and a novel analogue, Onnamide G, as potent leishmanicidal agents. Mar. Biotechnol. 2025, 27, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyakawa, K.; Matsunaga, S.; Yamaoka, Y.; Dairaku, M.; Fukano, K.; Kimura, H.; Chimuro, T.; Nishitsuji, H.; Watashi, K.; Shimotohno, K.; et al. Development of a cell-based assay to identify hepatitis B virus entry inhibitors targeting the sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 23681–23694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volz, T.; Allweiss, L.; Ben ḾBarek, M.; Warlich, M.; Lohse, A.W.; Pollok, J.M.; Alexandrov, A.; Urban, S.; Petersen, J.; Lütgehetmann, M.; et al. The entry inhibitor Myrcludex-B efficiently blocks intrahepatic virus spreading in humanized mice previously infected with hepatitis B virus. J. Hepatol. 2013, 58, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukano, K.; Tsukuda, S.; Oshima, M.; Suzuki, R.; Aizaki, H.; Ohki, M.; Park, S.-Y.; Muramatsu, M.; Wakita, T.; Sureau, C.; et al. Troglitazone impedes the oligomerization of sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide and entry of hepatitis B virus into hepatocytes. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.-W.; Su, I.-J.; Chang, W.-T.; Huang, W.; Lei, H.-Y. Suppression of p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Inhibits Hepatitis B Virus Replication in Human Hepatoma Cell: The Antiviral Role of Nitric Oxide. J. Viral Hepat. 2008, 15, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.; Li, L.; Cui, X.; Piao, L.; Cui, Z. Chlorogenic Acid Inhibition HBV Replication by Suppressed JNK Expression. Clin. Med. Res. 2024, 13, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, M.; Gong, R.; Wang, Z.; Lu, L.; Peng, S.; Duan, Z.; Feng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gao, B. Forkhead O Transcription Factor 4 Restricts HBV Covalently Closed Circular DNA Transcription and HBV Replication through Genetic Downregulation of Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4 Alpha and Epigenetic Suppression of Covalently Closed Circular DNA via Interacting with Promyelocytic Leukemia Protein. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e00546-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Liu, C.-D.; Shen, S.; Kim, E.S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Sun, N.; Liu, Y.; Martensen, P.M.; Huang, Y.; et al. Interferon alpha-inducible protein 27 (IFI27) inhibits hepatitis B virus (HBV) transcription through downregulating cellular transcription factor C/EBPα. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e01509-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Xu, K.; Tao, N.; Cheng, S.; Chen, H.; Zhang, D.; Yang, M.; Tan, M.; Yu, H.; Chen, P.; et al. ZNF148 inhibits HBV replication by downregulating RXRα transcription. Virol. J. 2024, 21, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, S.; Li, K.; Kameyama, T.; Hayashi, T.; Ishida, Y.; Murakami, S.; Watanabe, T.; Iijima, S.; Sakurai, Y.; Watashi, K.; et al. The RNA Sensor RIG-I Dually Functions as an Innate Sensor and Direct Antiviral Factor for Hepatitis B Virus. Immunity 2015, 42, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shionoya, K.; Park, J.-H.; Ekimoto, T.; Takeuchi, J.S.; Mifune, J.; Morita, T.; Ishimoto, N.; Umezawa, H.; Yamamoto, K.; Kobayashi, C.; et al. Structural basis for hepatitis B virus restriction by a viral receptor homologue. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melegari, M.; Wolf, S.K.; Schneider, R.J. Hepatitis B Virus DNA Replication Is Coordinated by Core Protein Serine Phosphorylation and HBx Expression. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 9810–9820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, M.; Cai, D.; Sugiyama, M.; Suzuki, R.; Aizaki, H.; Ryo, A.; Ohtani, N.; Tanaka, Y.; Mizokami, M.; Wakita, T.; et al. Functional Association of Cellular Microtubules with Viral Capsid Assembly Supports Efficient Hepatitis B Virus Replication. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirt, B. Selective extraction of polyoma DNA from infected mouse cell cultures. J. Mol. Biol. 1967, 26, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmström, S.; Larsson, S.B.; Hannoun, C.; Lindh, M. Hepatitis B Viral DNA Decline at Loss of HBeAg Is Mainly Explained by Reduced cccDNA Load—Down-Regulated Transcription of pgRNA Has Limited Impact. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allweiss, L.; Testoni, B.; Yu, M.; Lucifora, J.; Ko, C.; Qu, B.; Lütgehetmann, M.; Guo, H.; Urban, S.; Fletcher, S.P.; et al. Quantification of the hepatitis B virus cccDNA: Evidence-based guidelines for monitoring the key obstacle of HBV cure. Gut 2023, 72, 972–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, E.; Ma, Z.; Pei, R.; Jiang, M.; Schlaak, J.F.; Roggendorf, M.; Lu, M. Modulation of hepatitis B virus replication and hepatocyte differentiation by MicroRNA-1. Hepatology 2011, 53, 1476–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hayashi, Y.; Arizono, S.; Higa, N.; Tyas, T.A.; Akahori, Y.; Maeda, K.; Toyama, M.; Mori-Yasumoto, K.; Yasumoto-Hirose, M.; Miyakawa, K.; et al. Onnamides A and B Suppress Hepatitis B Virus Transcription by Inhibiting Viral Promoter Activity. Mar. Drugs 2026, 24, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010021

Hayashi Y, Arizono S, Higa N, Tyas TA, Akahori Y, Maeda K, Toyama M, Mori-Yasumoto K, Yasumoto-Hirose M, Miyakawa K, et al. Onnamides A and B Suppress Hepatitis B Virus Transcription by Inhibiting Viral Promoter Activity. Marine Drugs. 2026; 24(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleHayashi, Yasuhiro, Sei Arizono, Nanami Higa, Trianda Ayuning Tyas, Yuichi Akahori, Kenji Maeda, Masaaki Toyama, Kanami Mori-Yasumoto, Mina Yasumoto-Hirose, Kei Miyakawa, and et al. 2026. "Onnamides A and B Suppress Hepatitis B Virus Transcription by Inhibiting Viral Promoter Activity" Marine Drugs 24, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010021

APA StyleHayashi, Y., Arizono, S., Higa, N., Tyas, T. A., Akahori, Y., Maeda, K., Toyama, M., Mori-Yasumoto, K., Yasumoto-Hirose, M., Miyakawa, K., Tanaka, J., & Jomori, T. (2026). Onnamides A and B Suppress Hepatitis B Virus Transcription by Inhibiting Viral Promoter Activity. Marine Drugs, 24(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010021