Enhancing Astaxanthin Production in Paracoccus marcusii Using an Integrated Strategy: Breeding a Novel Mutant and Fermentation Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Optimal Conditions Determination of EMS-UV-ARTP Compound Mutagenesis

2.2. High-Throughput Culture in the MMC System for Top Microdroplets Screening

2.3. Direct Isolation of Target Mutants on Dual-Inhibitor Selective Agar Plates

2.4. Evaluation and Identification of Optimal Mutant via Liquid Culture

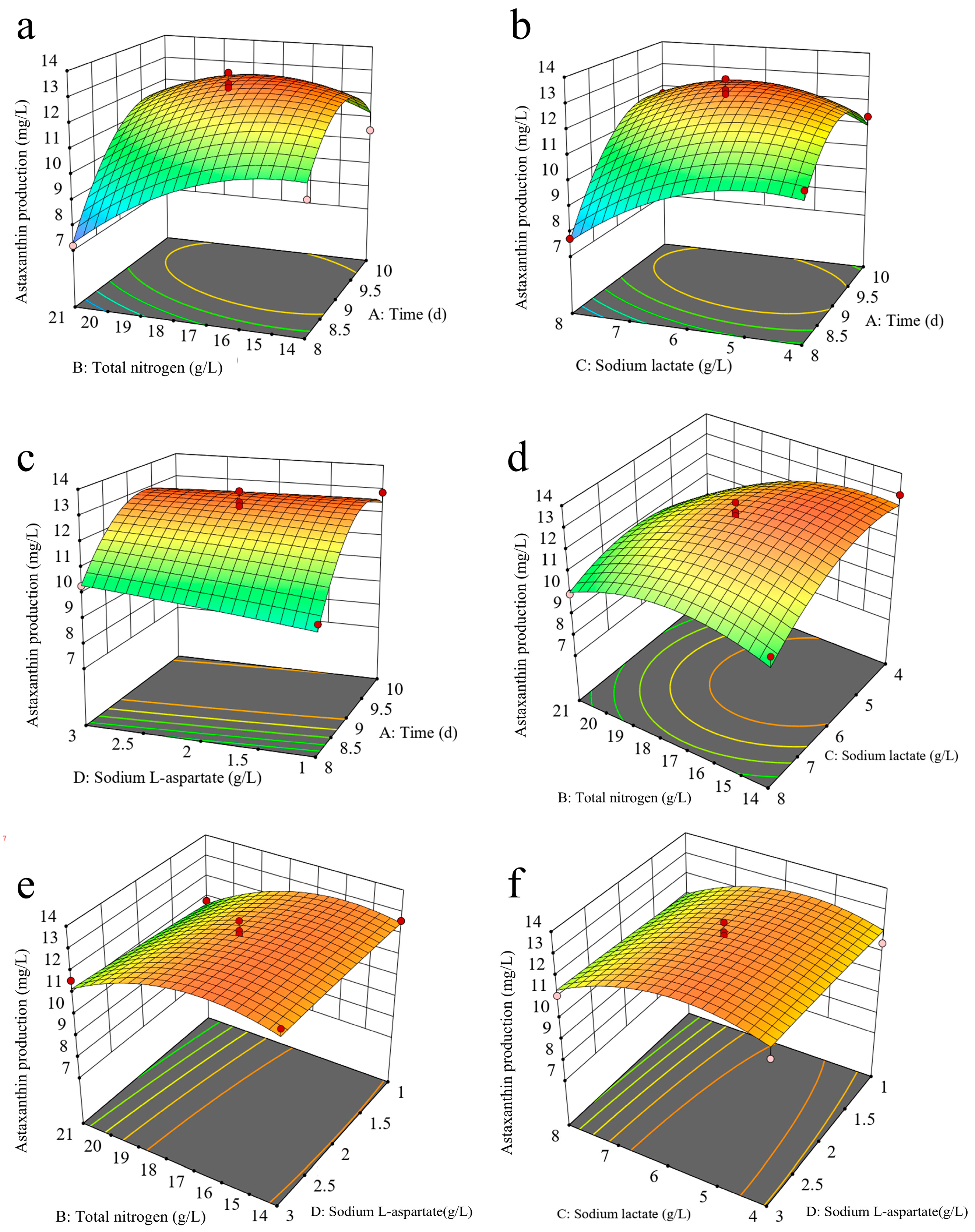

2.5. Optimization of Fermentation Conditions for Enhancing Astaxanthin Production

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Bacterial Strain and Seed Culture

3.2. Condition Optimization of EMS-UV-ARTP Compound Mutagenesis

3.2.1. Ethyl Methanesulfonate (EMS) Treatment

3.2.2. Ultraviolet (UV) Treatment

3.2.3. Atmospheric Room Temperature Plasma (ARTP) Treatment

3.3. High-Throughput Culture for Screening Fast-Growing Microdroplets in the MMC System

3.4. Mutants Isolation on Selective LB Agar Plates

3.5. Capacity Evaluation and Optimal Mutant Identification

3.6. Optimization of Fermentation Conditions

3.7. Analytical Methods

3.7.1. Cell Growth and Biomass Production

3.7.2. Astaxanthin

3.8. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raza, S.H.A.; Naqvi, S.R.Z.; Abdelnour, S.A.; Schreurs, N.; Mohammedsaleh, Z.M.; Khan, I.; Shater, A.F.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Khafaga, A.F.; Quan, G.B.; et al. Beneficial effects and health benefits of Astaxanthin molecules on animal production: A review. Res. Vet. Sci. 2021, 138, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, A.; Saini, K.C.; Bast, F.; Mehariya, S.; Bhatia, S.K.; Lavecchia, R.; Zuorro, A. Microorganisms: A Potential Source of Bioactive Molecules for Antioxidant Applications. Molecules 2021, 26, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Fei, Z.; Liu, G.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Lin, C.S.K.; Zhang, W.; Xin, F.; Jiang, M. The bioproduction of astaxanthin: A comprehensive review on the microbial synthesis and downstream extraction. Biotechnol. Adv. 2024, 74, 108392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, T.; Bandyopadhyay, T.K.; Vanitha, K.; Bobby, M.N.; Tiwari, O.N.; Bhunia, B.; Muthuraj, M. Astaxanthin from microalgae: A review on structure, biosynthesis, production strategies and application. Food Res. Int. 2024, 176, 133841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.P.; Tian, C.X.; Zhu, K.C.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Jiang, M.Y.; Zhu, C.H.; Li, G.L. Effects of Natural and Synthetic Astaxanthin on Growth, Body Color, and Transcriptome and Metabolome Profiles in the Leopard Coralgrouper (Plectropomus leopardus). Animals 2023, 13, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.W.; Yang, X.Y.; Wang, H.X.; Jiang, Y.J.; Jiang, W.K.; Zhang, W.M.; Jiang, M.; Xin, F.X. Biosynthesis of astaxanthin by using industrial yeast. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2023, 17, 602–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekanov, K. Diversity and Distribution of Carotenogenic Algae in Europe: A Review. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kratzer, R.; Murkovic, M. Food Ingredients and Nutraceuticals from Microalgae: Main Product Classes and Biotechnological Production. Foods 2021, 10, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannel, S.; Caro, Y.; Bermudes, M.; Petit, T. Exploration of the Biotechnological Potential of Two Newly Isolated Haematococcus Strains from Reunion Island for the Production of Natural Astaxanthin. Foods 2024, 13, 3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, M.; Ishibashi, T.; Kuwahara, D.; Hirasawa, K. Commercial Production of Astaxanthin with Paracoccus carotinifaciens. In Carotenoids: Biosynthetic and Biofunctional Approaches; Misawa, N., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 1261, pp. 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- La Tella, R.; Tropea, A.; Rigano, F.; Giuffrida, D.; Micalizzi, G.; Salerno, T.M.G.; Mussagy, C.U.; Kim, B.S.; Jantharadej, K.; Zinno, P.; et al. Identification of the wild type bacterium Paracoccus sp. LL1 as a promising β-carotene cell factory. Food Biosci. 2025, 63, 105616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, A.; Kim, B.S. Enhanced Production of Astaxanthin and Zeaxanthin by Paracoccus Sp. LL1 Through Random Mutagenesis. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.S.; Seo, Y.B.; Nam, S.W.; Kim, G.D. Enhanced Production of Astaxanthin by Co-culture of Paracoccus haeundaensis and Lactic Acid Bacteria. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 7, 597553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.J.; Li, B.X.; Zhang, N.; Wei, N.; Wang, Q.F.; Wang, W.J.; Xie, Y.W.; Zou, H.T. Salt stress increases carotenoid production of Sporidiobolus pararoseus NGR via torulene biosynthetic pathway. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 65, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.A.; Wang, X. Use of bacterial co-cultures for the efficient production of chemicals. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 53, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ide, T.; Hoya, M.; Tanaka, T.; Harayama, S. Enhanced production of astaxanthin in Paracoccus sp. strain N-81106 by using random mutagenesis and genetic engineering. Biochem. Eng. J. 2012, 65, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovão, M.; Schüler, L.M.; Machado, A.; Bombo, G.; Navalho, S.; Barros, A.; Pereira, H.; Silva, J.; Freitas, F.; Varela, J. Random Mutagenesis as a Promising Tool for Microalgal Strain Improvement towards Industrial Production. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T.S.; Zhao, H. Increasing chitosanase production in Bacillus cereus by a novel mutagenesis and screen method. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Wei, D.; Xing, X. Breeding a novel chlorophyll-deficient mutant of Auxenochlorella pyrenoidosa for high-quality protein production by atmospheric room temperature plasma mutagenesis. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 390, 129907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Y.; Huang, Z.L.; Li, G.; Zhao, H.X.; Xing, X.H.; Sun, W.T.; Li, H.P.; Gou, Z.X.; Bao, C.Y. Novel mutation breeding method for Streptomyces avermitilis using an atmospheric pressure glow discharge plasma. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 108, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xia, Y.; Li, M.L.; Zhang, T. ARTP mutagenesis of phospholipase D-producing strain Streptomyces hiroshimensis SK43.001, and its enzymatic properties. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, X.; Guo, X.; Wang, J.; Tan, Z.L.; Xing, X.H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C. Microbial microdroplet culture system (MMC): An integrated platform for automated, high-throughput microbial cultivation and adaptive evolution. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2020, 117, 1724–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Y.; Jiang, G.-L.; Zhu, M.-J. Atmospheric and room temperature plasma mutagenesis and astaxanthin production from sugarcane bagasse hydrolysate by Phaffia rhodozyma mutant Y1. Process Biochem. 2020, 91, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Wei, D.; Xing, X. Rapid screening of high-protein Auxenochlorella pyrenoidosa mutant by an integrated system of atmospheric and room temperature plasma mutagenesis and high-throughput microbial microdroplet culture. Algal Res. 2024, 80, 103509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Haro, A.; Verdín, J.; Kirchmayr, M.R.; Arellano-Plaza, M. Metabolic engineering for high yield synthesis of astaxanthin in Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. Microb. Cell Factories 2021, 20, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Guan, B.; Kong, Q.; Sun, H.; Geng, Z.; Duan, L. Enhancement of astaxanthin production from Haematococcus pluvialis mutants by three-stage mutagenesis breeding. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 236, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Su, Y.; Xu, M.; Bergmann, A.; Ingthorsson, S.; Rolfsson, O.; Salehi-Ashtiani, K.; Brynjolfsson, S.; Fu, W. Chemical Mutagenesis and Fluorescence-Based High-Throughput Screening for Enhanced Accumulation of Carotenoids in a Model Marine Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Flores, C.H.; Wang, A.; von Hellens, J.; Speight, R.E. Towards commercial levels of astaxanthin production in Phaffia rhodozyma. J. Biotechnol. 2022, 350, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiony, M.; Ouyang, L.; Wang, D.; Yu, J.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, M.; Wang, X.; Feng, J.; Dai, J.; Shen, Y.; et al. Optimization of microbial cell factories for astaxanthin production: Biosynthesis and regulations, engineering strategies and fermentation optimization strategies. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2022, 7, 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, F.S.; Khaw, S.Y.; Few, L.L.; See Too, W.C.; Chew, A.L. Isolation of a Stable Astaxanthin-Hyperproducing Mutant of Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous Through Random Mutagenesis. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2019, 55, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Li, Y.; Wu, B.; Hu, W.; He, M.; Hu, G. Novel mutagenesis and screening technologies for food microorganisms: Advances and prospects. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 1517–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Wang, Y.; Yao, M.; Gu, X.; Li, B.; Liu, H.; Ding, M.; Xiao, W.; Yuan, Y. Astaxanthin overproduction in yeast by strain engineering and new gene target uncovering. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, U.; Venkateshwaran, G.; Sarada, R.; Ravishankar, G.A. Studies on Haematococcus pluvialis for improved production of astaxanthin by mutagenesis. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 17, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.-Y.; Chen, L.-C.; Li, Y.-C.M.; Hsu, H.-L.; Huang, C.-M. Response Surface Methodology Optimization in High-Performance Solid-State Supercapattery Cells Using NiCo2S4–Graphene Hybrids. Molecules 2022, 27, 6867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quanhong, L.; Caili, F. Application of response surface methodology for extraction optimization of germinant pumpkin seeds protein. Food Chem. 2005, 92, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Zhang, C.; Suglo, P.; Sun, S.; Wang, M.; Su, T. l-Aspartate: An Essential Metabolite for Plant Growth and Stress Acclimation. Molecules 2021, 26, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbachano-Torres, A.; Castelblanco-Matiz, L.M.; Ramos-Valdivia, A.C.; Cerda-García-Rojas, C.M.; Salgado, L.M.; Flores-Ortiz, C.M.; Ponce-Noyola, T. Analysis of proteomic changes in colored mutants of Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous (Phaffia rhodozyma). Arch. Microbiol. 2014, 196, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harker, M.; Hirschberg, J.; Oren, A. Paracoccus marcusii sp. nov., an orange Gram-negative coccus. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1998, 48, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomlaem, C.; Aloui, H.; Oh, W.-G.; Kim, B.S. High cell density culture of Paracoccus sp. LL1 in membrane bioreactor for enhanced co-production of polyhydroxyalkanoates and astaxanthin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 192, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadebe, S.T.; Modi, A.T.; Odindo, A.O.; Shimelis, H.A. Inducing genetic mutation on selected vernonia accessions using predetermined ethylmethanesulfonate dosage, temperature regime and exposure duration conditions. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2018, 119, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.B.; Jeong, T.; Choi, S.; Lim, H.; Kim, G.-D. Enhanced Production of Astaxanthin in Paracoccus haeundaensis Strain by Physical and Chemical Mutagenesis. J. Life Sci. 2017, 27, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhou, J.J.; Pickett, J.A.; Wu, K. Plant volatile analogues strengthen attractiveness to insect. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yang, R.; Pohnert, G.; Wei, D. Insights from an integrated multi-omics analysis: The synergistic effect of arginine and urea in marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 522, 167926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. Microdroplet | μ (h−1) | No. Microdroplet | μ (h−1) | No. Microdroplet | μ (h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.87 | 5 | 0.71 | 12 | 0.67 |

| 3 | 0.86 | 15 | 0.70 | 23 | 0.66 |

| 4 | 0.82 | 11 | 0.70 | 22 | 0.66 |

| 6 | 0.79 | 8 | 0.69 | 16 | 0.65 |

| 17 | 0.78 | 18 | 0.68 | 24 | 0.61 |

| 9 | 0.77 | 7 | 0.68 | 21 | 0.60 |

| 13 | 0.73 | 19 | 0.68 | 2 | 0.60 |

| 14 | 0.71 | 20 | 0.67 | 18 | 0.68 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 59.12 | 14 | 4.22 | 14.29 | <0.0001 | ** |

| A | 17.02 | 1 | 17.02 | 57.60 | <0.0001 | ** |

| B | 7.11 | 1 | 7.11 | 24.05 | 0.0002 | ** |

| C | 2.67 | 1 | 2.67 | 9.04 | 0.0094 | ** |

| D | 0.1984 | 1 | 0.1984 | 0.6711 | 0.4264 | - |

| AB | 3.04 | 1 | 3.04 | 10.28 | 0.0063 | ** |

| AC | 2.55 | 1 | 2.55 | 8.63 | 0.0108 | * |

| AD | 0.3749 | 1 | 0.3749 | 1.27 | 0.2790 | - |

| BC | 1.39 | 1 | 1.39 | 4.69 | 0.0481 | * |

| BD | 0.0946 | 1 | 0.0946 | 0.3202 | 0.5804 | - |

| CD | 0.0085 | 1 | 0.0085 | 0.0288 | 0.8678 | - |

| A2 | 17.49 | 1 | 17.49 | 59.18 | <0.0001 | ** |

| B2 | 6.33 | 1 | 6.33 | 21.40 | 0.0004 | ** |

| C2 | 6.89 | 1 | 6.89 | 23.31 | 0.0003 | ** |

| D2 | 0.0106 | 1 | 0.0106 | 0.0358 | 0.8527 | - |

| Residual | 4.14 | 14 | 0.2956 | - | - | - |

| Lack-of-Fit | 3.13 | 10 | 0.3134 | 1.25 | 0.4487 | No significance |

| Pure error | 1.00 | 4 | 0.2511 | - | - | - |

| Total sum | 63.26 | 28 | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Huang, S.; Wei, D.; Pan, S. Enhancing Astaxanthin Production in Paracoccus marcusii Using an Integrated Strategy: Breeding a Novel Mutant and Fermentation Optimization. Mar. Drugs 2026, 24, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010019

Li Y, Huang S, Wei D, Pan S. Enhancing Astaxanthin Production in Paracoccus marcusii Using an Integrated Strategy: Breeding a Novel Mutant and Fermentation Optimization. Marine Drugs. 2026; 24(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yu, Shuyin Huang, Dong Wei, and Siyu Pan. 2026. "Enhancing Astaxanthin Production in Paracoccus marcusii Using an Integrated Strategy: Breeding a Novel Mutant and Fermentation Optimization" Marine Drugs 24, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010019

APA StyleLi, Y., Huang, S., Wei, D., & Pan, S. (2026). Enhancing Astaxanthin Production in Paracoccus marcusii Using an Integrated Strategy: Breeding a Novel Mutant and Fermentation Optimization. Marine Drugs, 24(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010019