Can Fascaplysins Be Considered Analogs of Indolo[2,3-a]pyrrolo[3,4-c]carbazoles? Comparison of Biosynthesis, Biological Activity and Therapeutic Potential

Abstract

1. Introduction

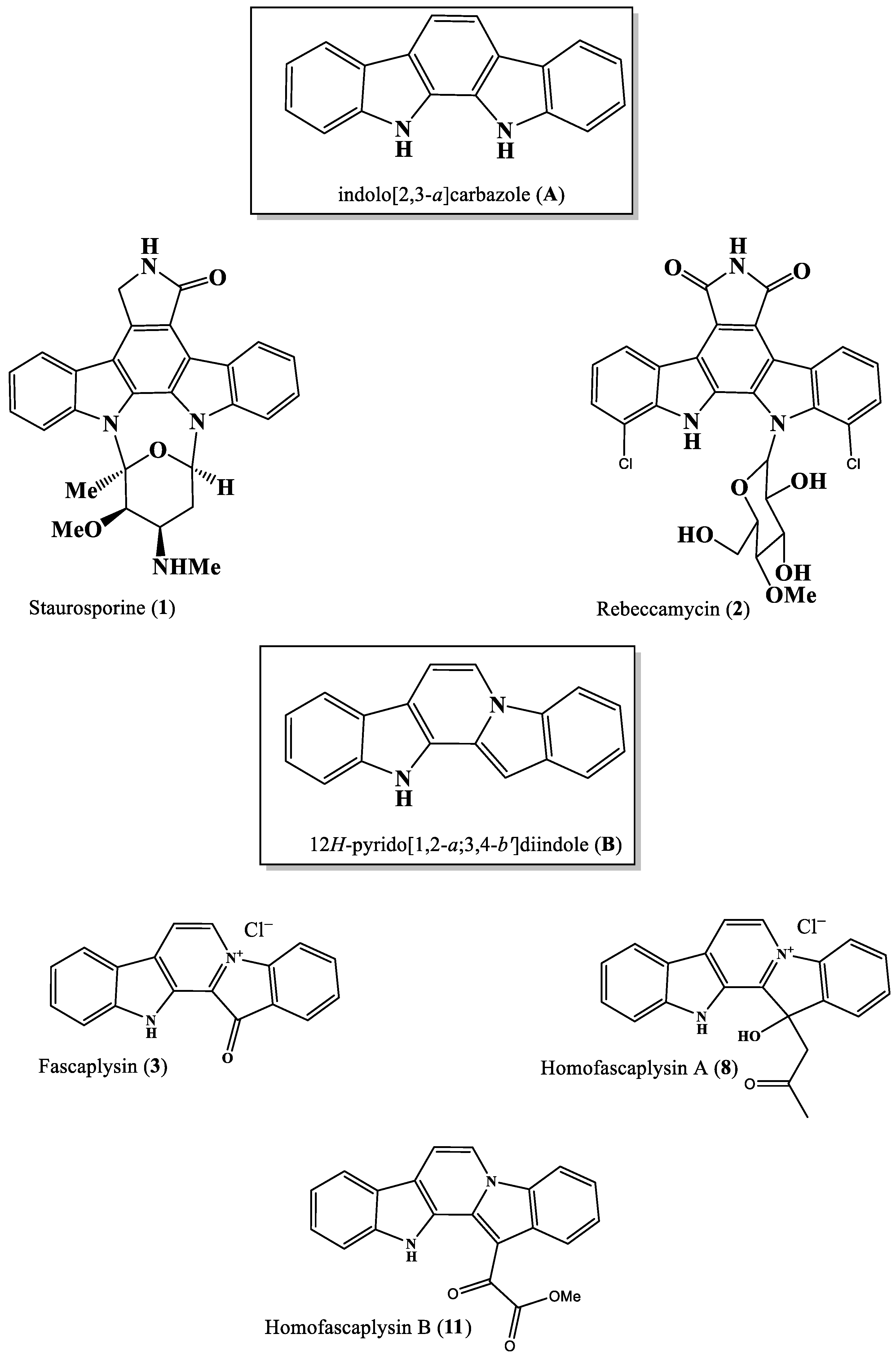

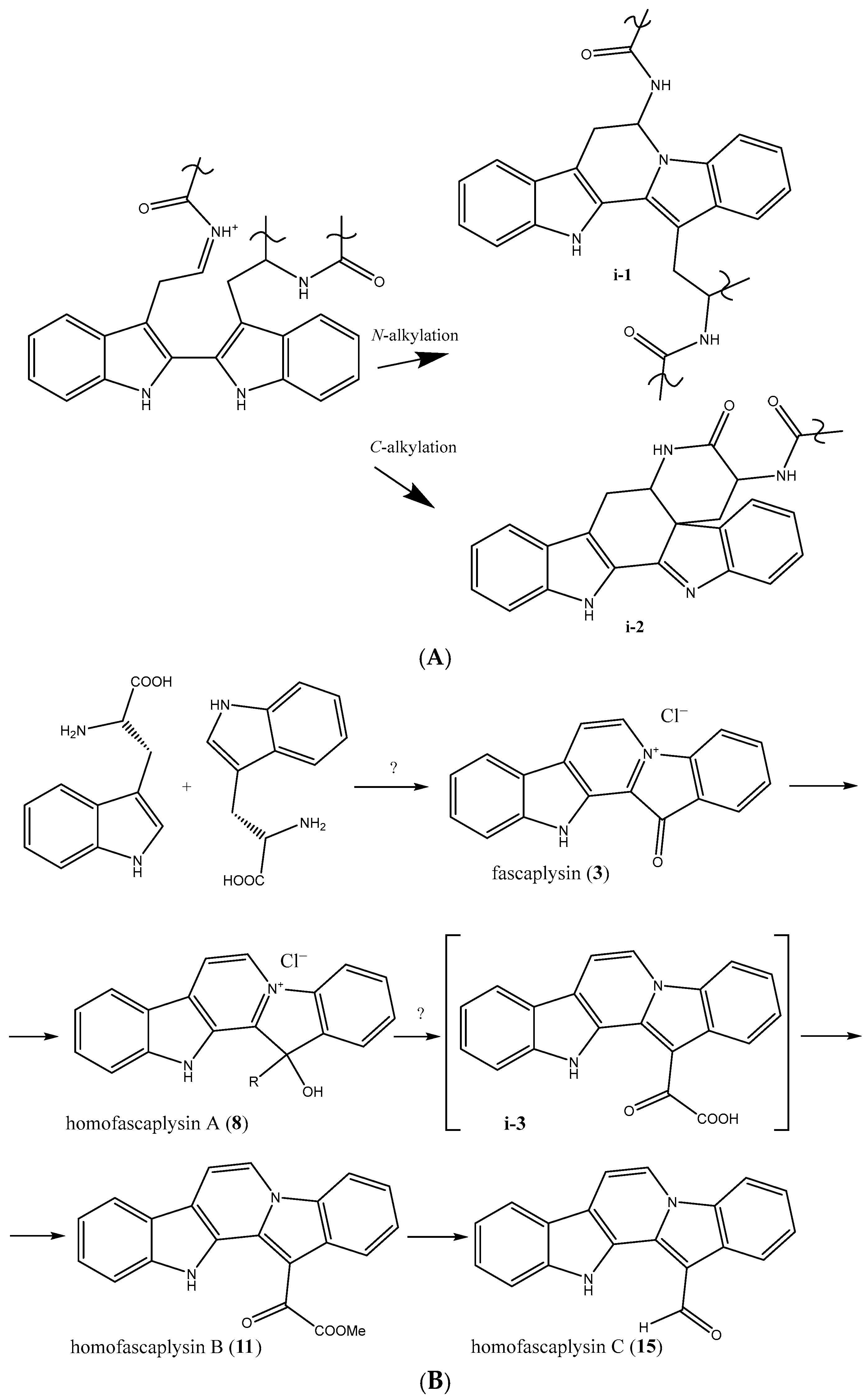

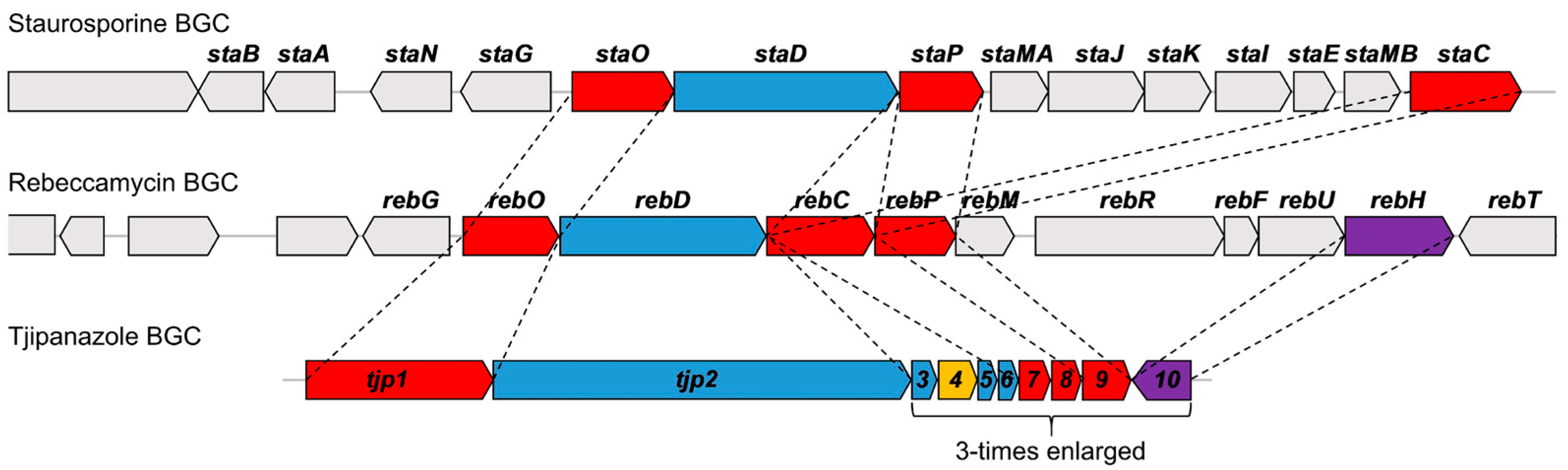

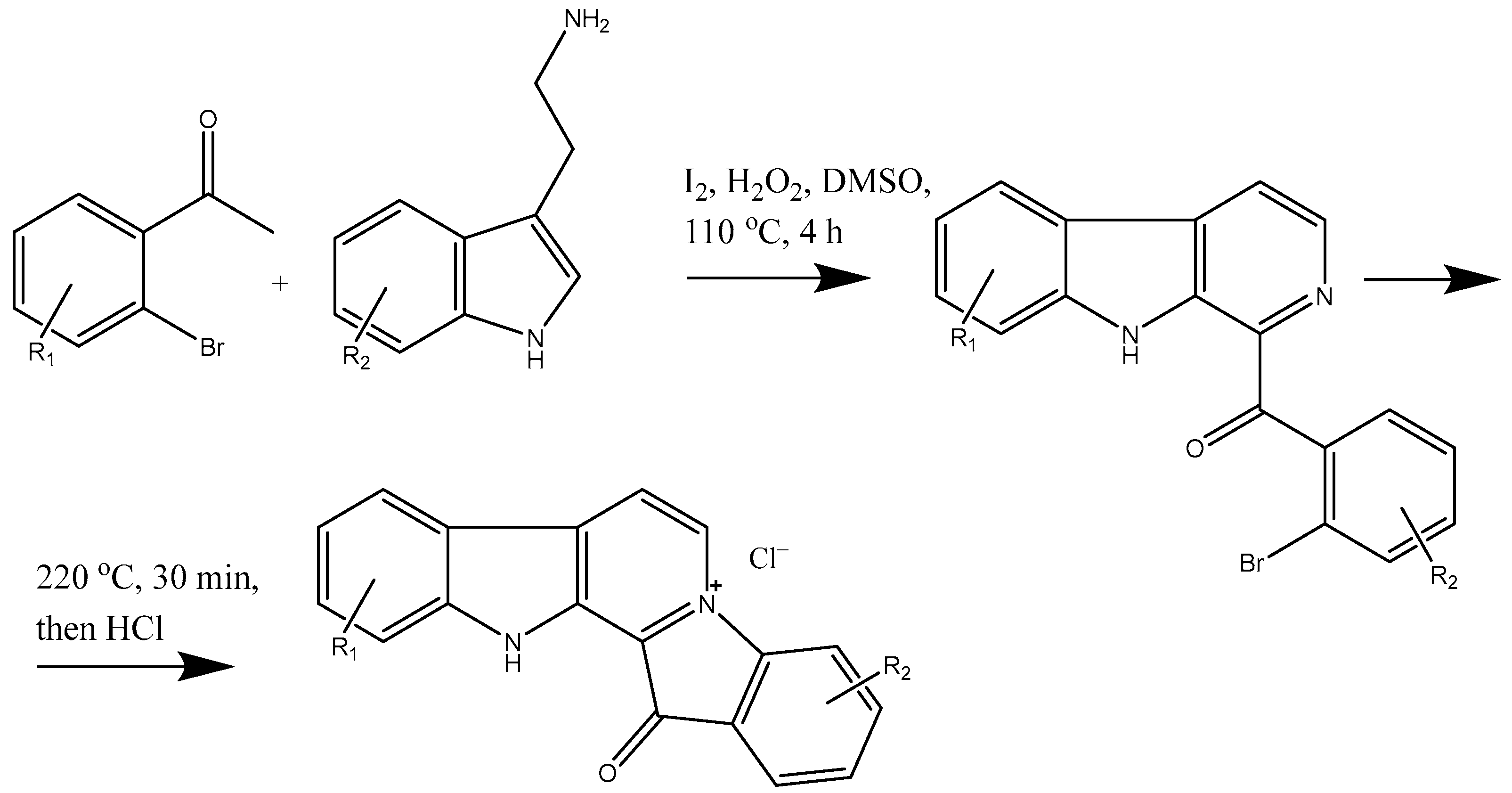

2. Biosynthetic Relationship Between 12H-Pyrido[1,2-a;3,4-b′]diindoles and Indolo[2,3-a]carbazoles

3. Biological Activity of Fascaplysins and Indolo[2,3-a]carbazoles In Vitro

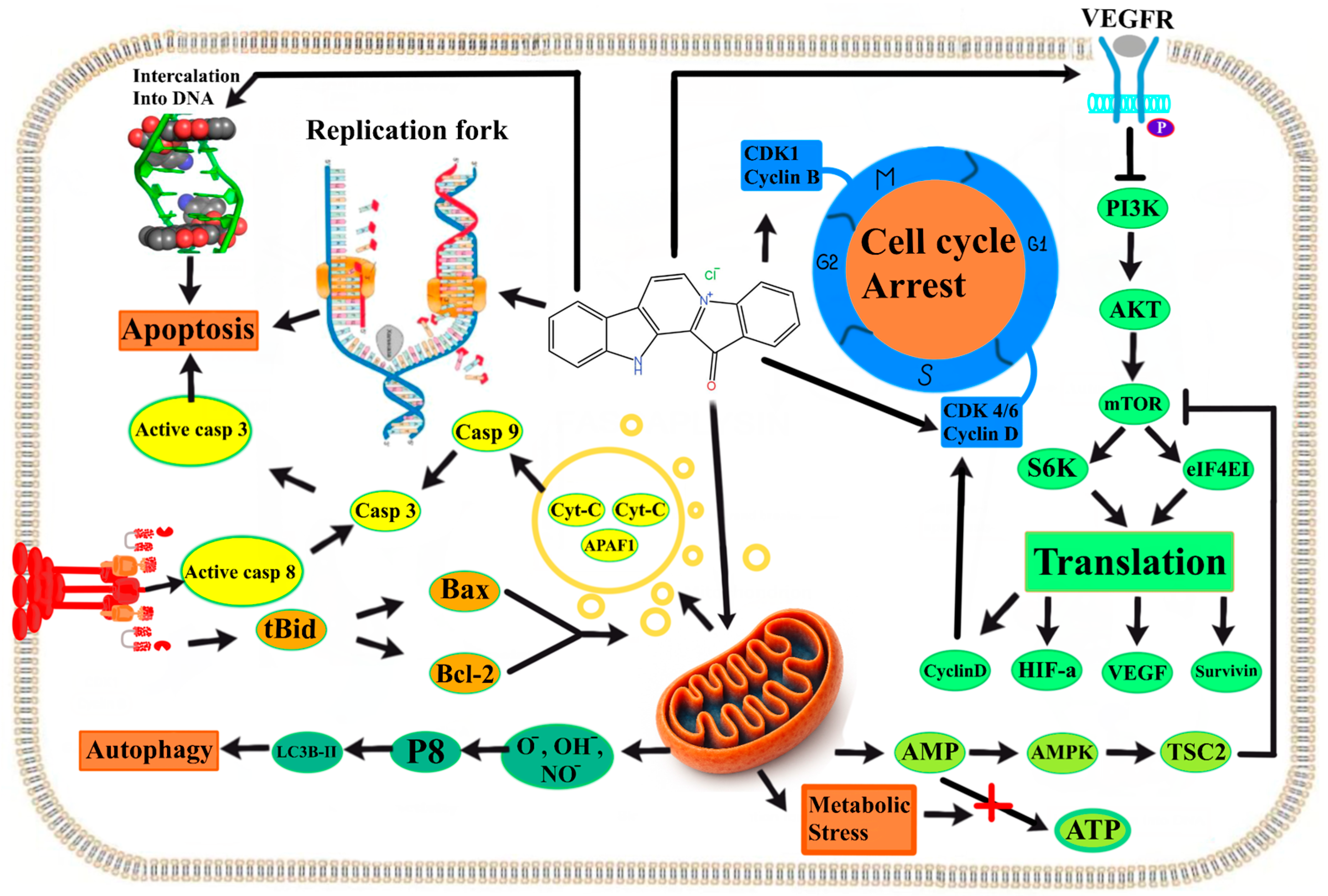

4. Mechanisms of Biological Activity of Indolo[2,3-a]carbazoles and Fascaplysins

5. Comparation of Properties of Natural Indolo[2,3-a]carbazoles and Fascaplysin In Vivo

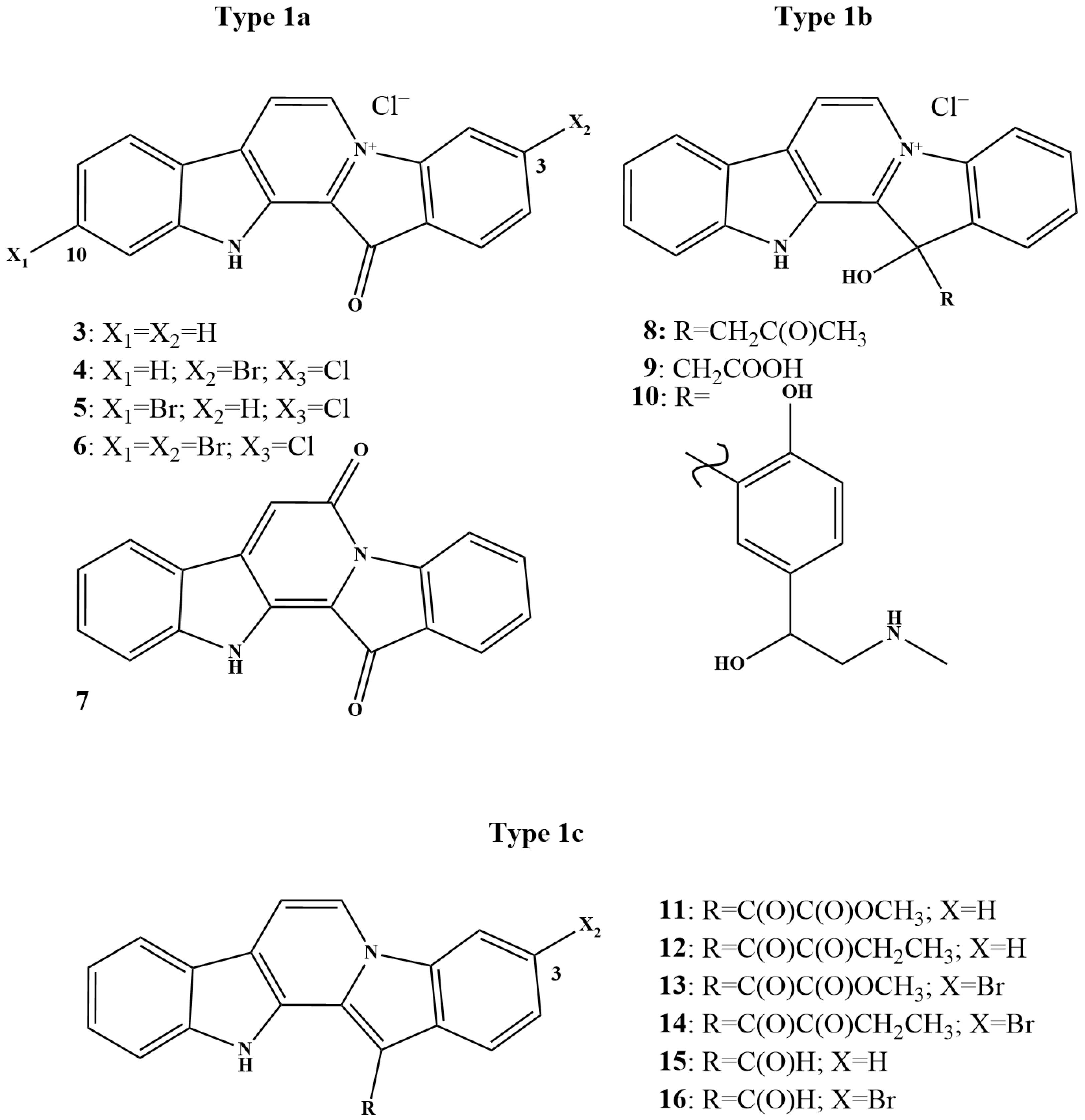

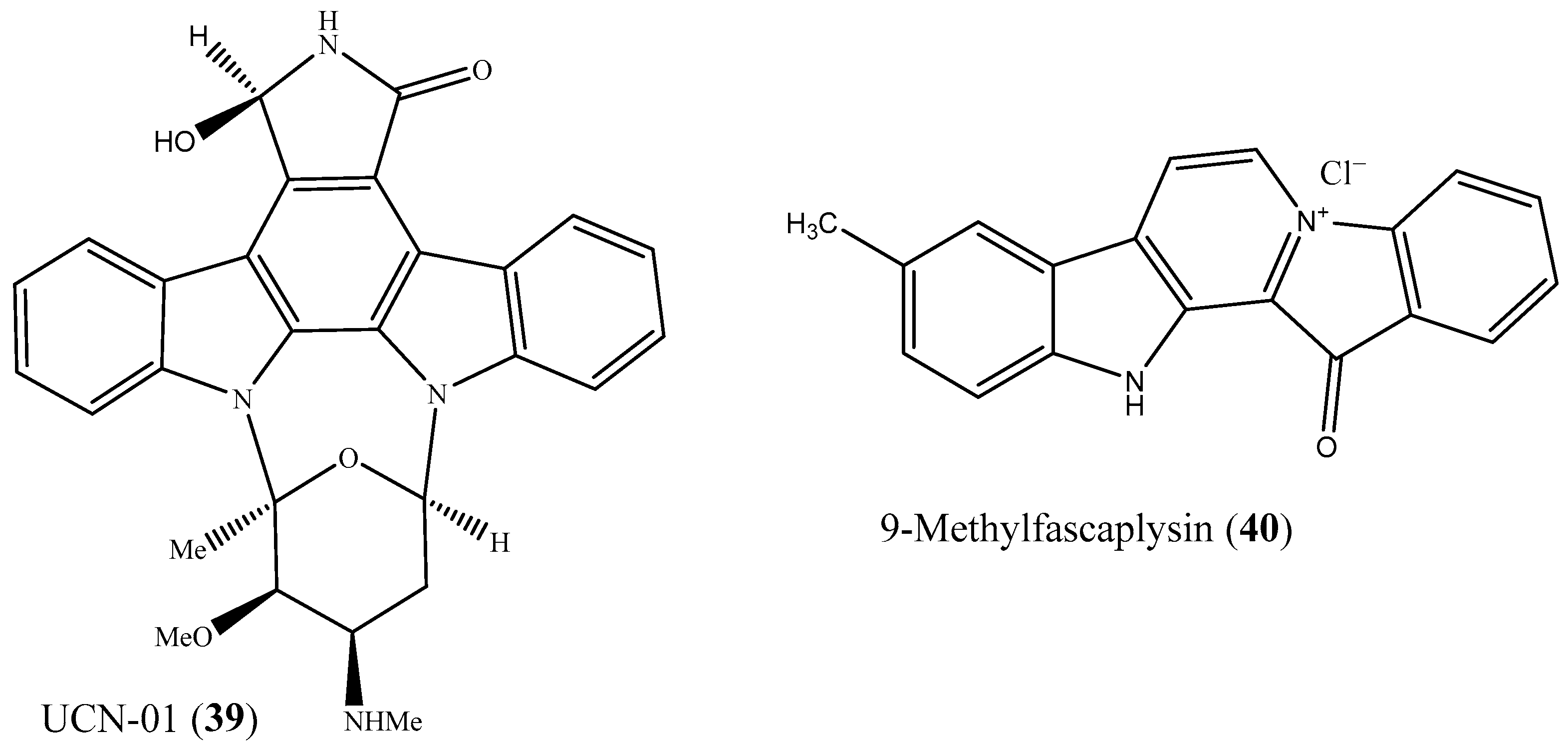

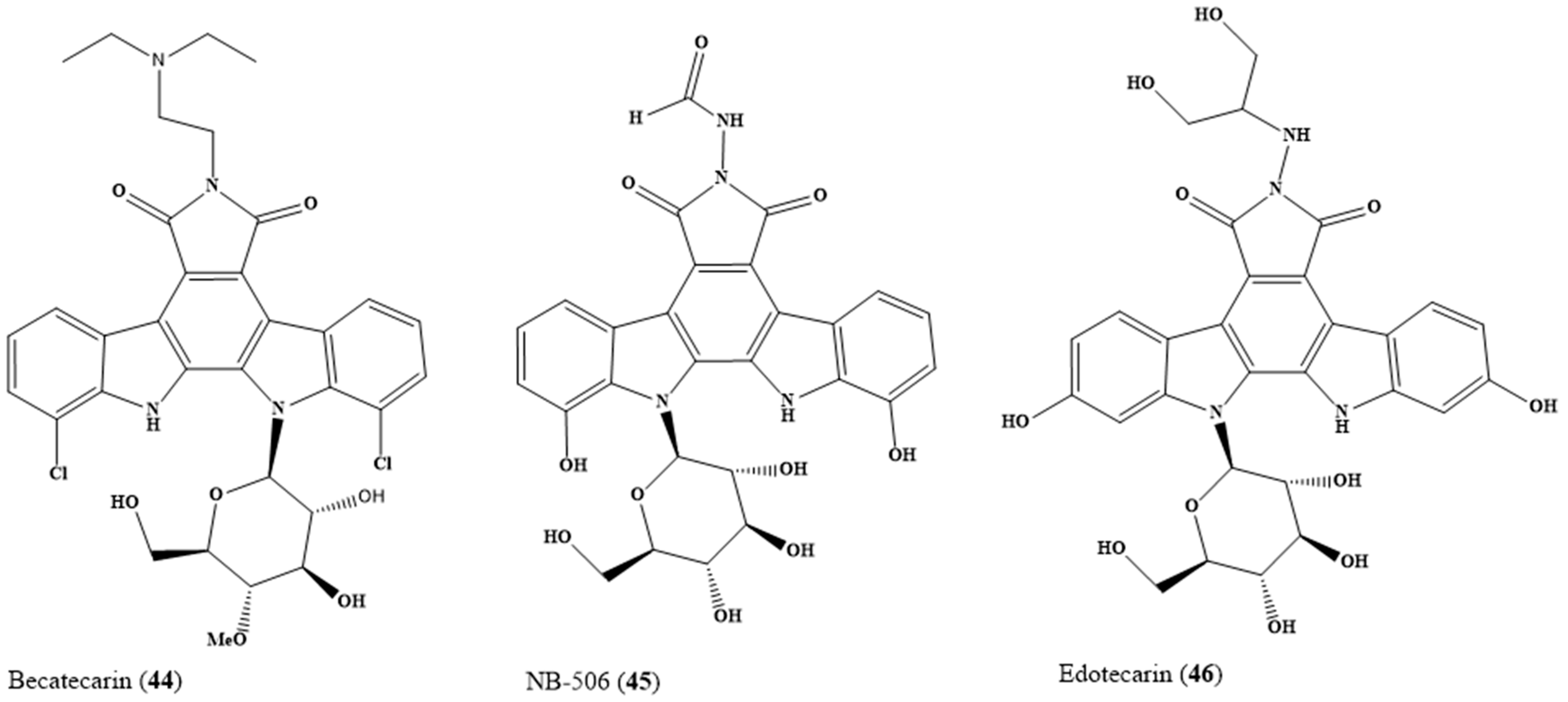

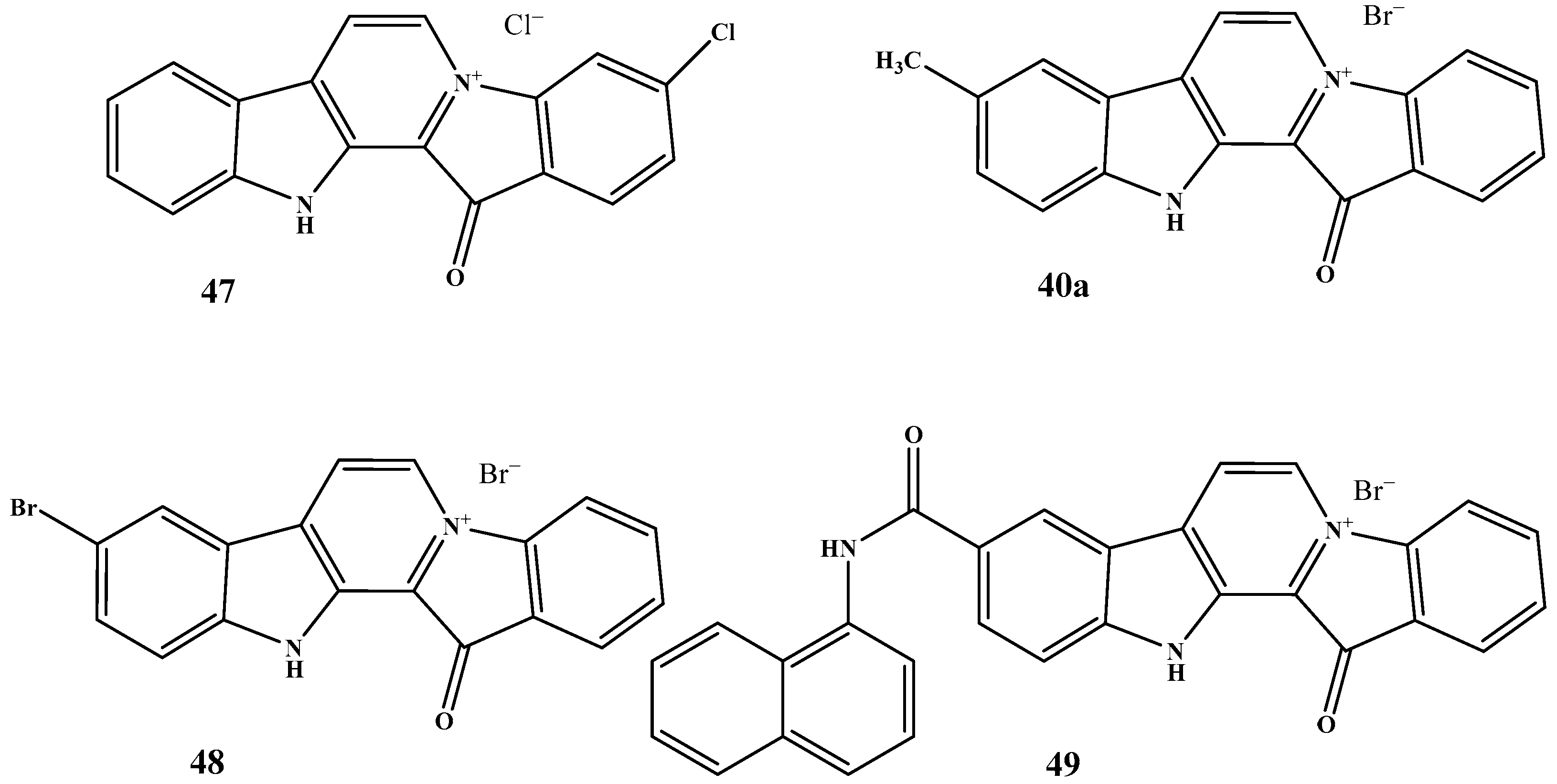

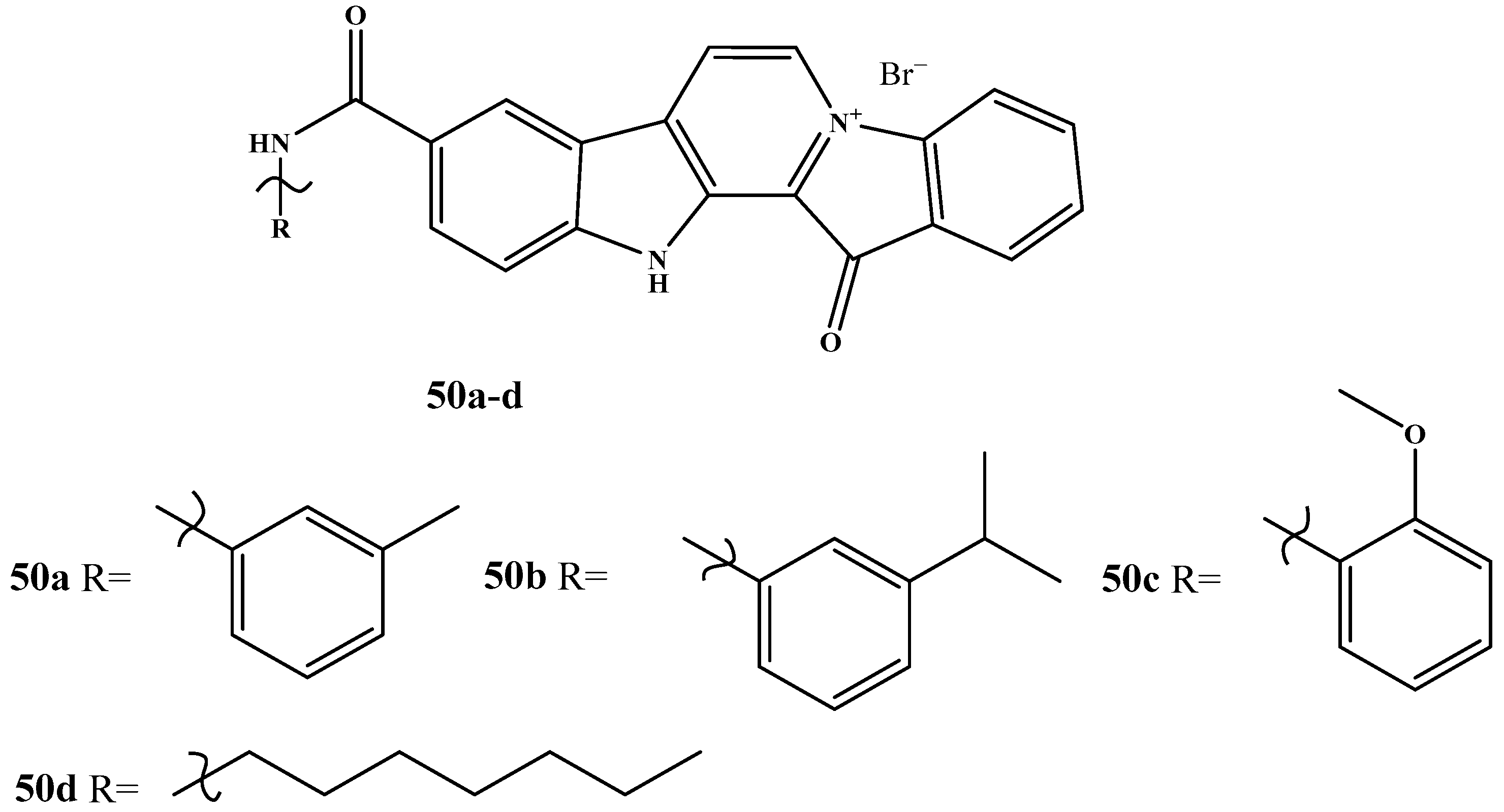

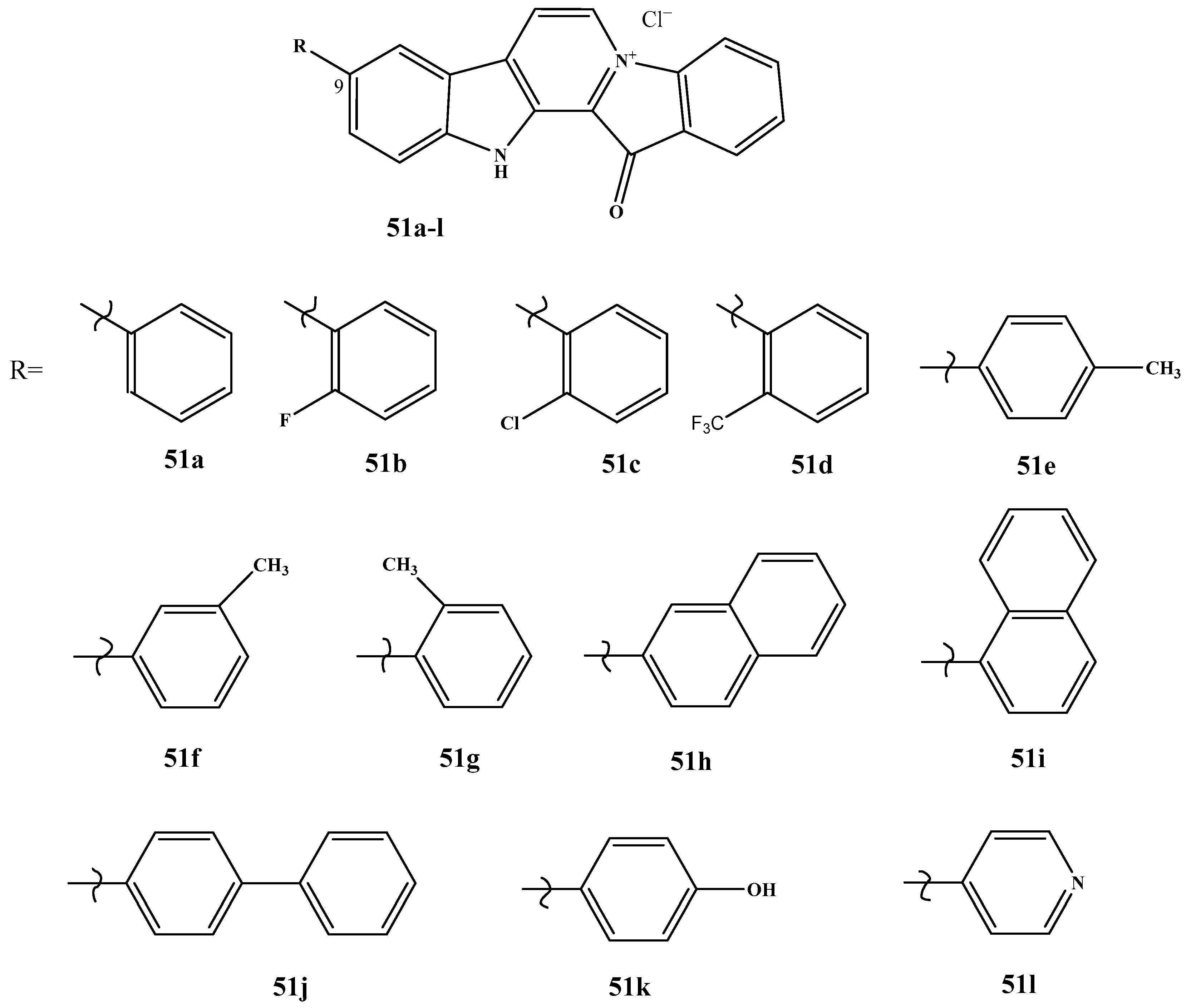

6. Lead Candidates Based on Indolo[2,3-a]carbazoles and 12H-Pyrido[1,2-a;3,4-b′]diindoles

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pomponi, S.A. The bioprocess—Technological potential of the sea. J. Biotechnol. 1999, 70, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyshlovoy, S.A.; Honecker, F. Marine compounds and cancer: The first two decades of XXI century. Mar. Drugs 2019, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.; Naughton, L.M.; Montanchez, I.; Dobson, A.D.W.; Rai, D.K. Current status and future prospects of marine natural products (MNPs) as antimicrobials. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonik, V.A. Marine natural products: A way to new drugs. Acta Nat. 2009, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F. Have marine natural product drug discovery efforts been productive and how can we improve their efficiency? Expert. Opin. Drug Discov. 2019, 14, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, I.; Anderson, E.A. The renaissance of natural products as drug candidates. Science 2005, 310, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenkov, R.G.; Ektova, L.V.; Vlasova, O.А.; Belitskiy, G.А.; Yakubovskaya, M.G.; Kirsanov, K.I. Indolo [2,3-a]carbazoles: Diversity, biological properties, application in antitumor therapy. Chem. Heterocycl. Comp. 2020, 56, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roll, D.M.; Ireland, C.M.; Lu, H.S.M.; Clardy, J. Fascaplysin, an unusual antimicrobial pigment from the marine sponge Fascaplysinopsis sp. J. Org. Chem. 1988, 53, 3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segraves, N.L.; Robinson, S.J.; Garcia, D.; Said, S.A.; Fu, X.; Schmitz, F.J.; Pietraszkiewicz, H.; Valeriote, F.A.; Crews, P. Comparison of fascaplysin and related alkaloids: A study of structures, cytotoxicities, and sources. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez, C.; Quinoa, E.; Adamczeski, M.; Hunter, L.M.; Crews, P. Novel sponge-derived amino acids. 12. Tryptophan-derived pigments and accompanying sesterterpenes from Fascaplysinopis reticulata. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, C.; Quinoa, E.; Crews, P. Novel marine sponge alkaloids 3. β-Carbolinium salts from Fascaplysinopsis reticulata. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991, 32, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, E.W.; Faulkner, D.J. Palauolol, a new anti-inflammatory sesterterpene from the sponge Fascaplysinopsis sp. from Palau. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, G.; Konig, G.M.; Wright, A.D.; Kaminsky, R. A new bioactive sesterterpene and antiplasmodial alkaloids from the marine sponge Hyrtios cf. erecta. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charan, R.D.; McKee, T.C.; Gustafson, K.R.; Pannell, L.K.; Boyd, M.R. Thorectandramine, a novel β-carboline alkaloid from the marine sponge Thorectandra sp. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 5201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khokhar, S.; Feng, Y.; Campitelli, M.R.; Ekins, M.G.; Hooper, J.N.A.; Beattie, K.D.; Sadowski, M.C.; Nelson, C.C.; Davis, R.A. Isolation, structure determination and cytotoxicity studies of tryptophan alkaloids from an Australian marine sponge Hyrtios sp. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, D.S.; Van Vranken, D.L. Synthesis of homofascaplysin C and indolo [2,3-a]carbazole from ditryptophans. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 8537–8545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, C.; Mendez, C.; Salas, J.A. Indolocarbazole natural products: Occurrence, biosynthesis, and biological activity. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2006, 23, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

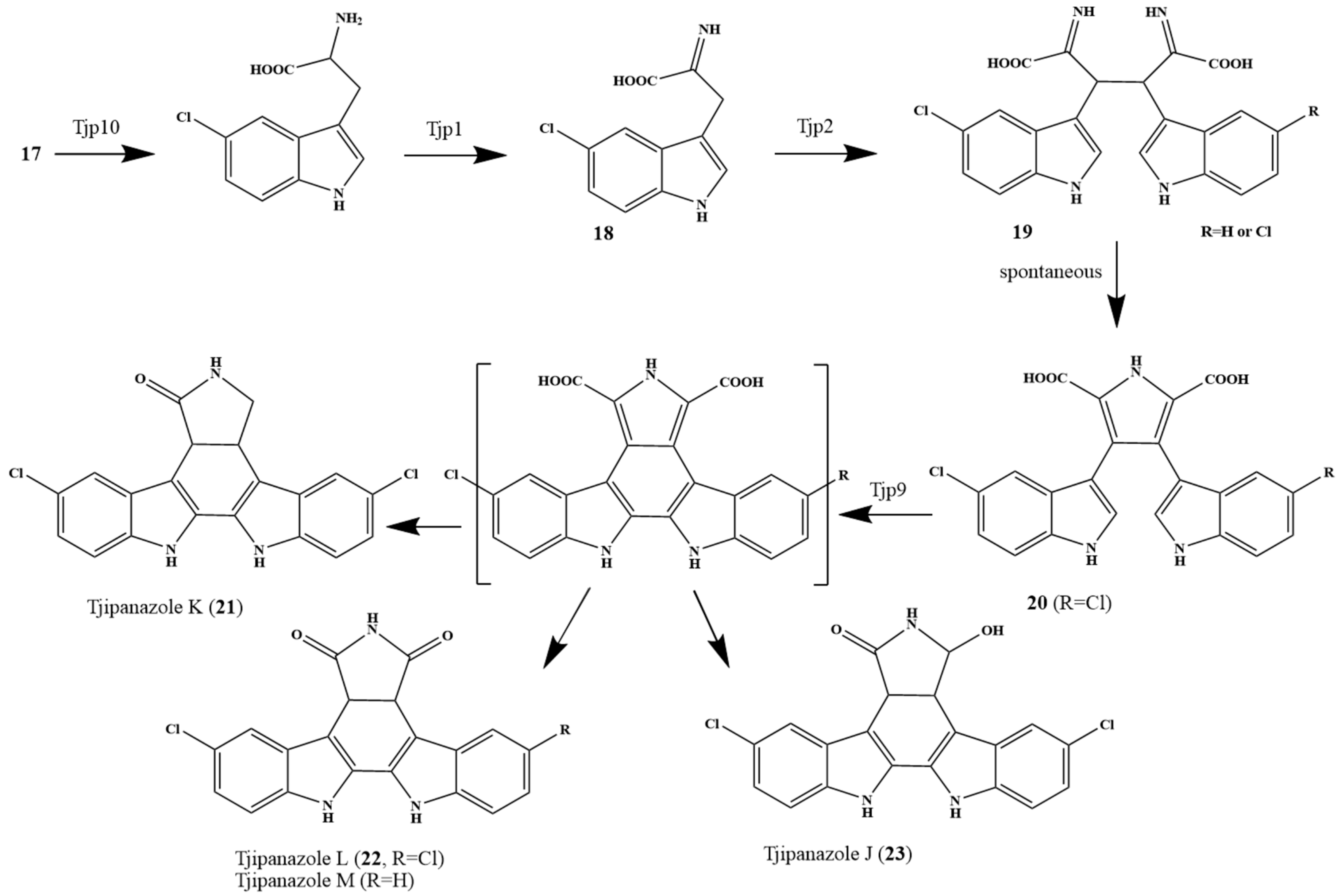

- Chilczuk, T.; Schaberle, T.F.; Vahdati, S.; Mettal, U.; El Omari, M.; Enke, H.; Wiese, M.; Konig, G.M.; Niedermeyer, T.H.J. Halogenation-guided chemical screening provides insight into tjipanazole biosynthesis by the cyanobacterium Fischerella ambigua. Chem. Bio. Chem. 2020, 21, 2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

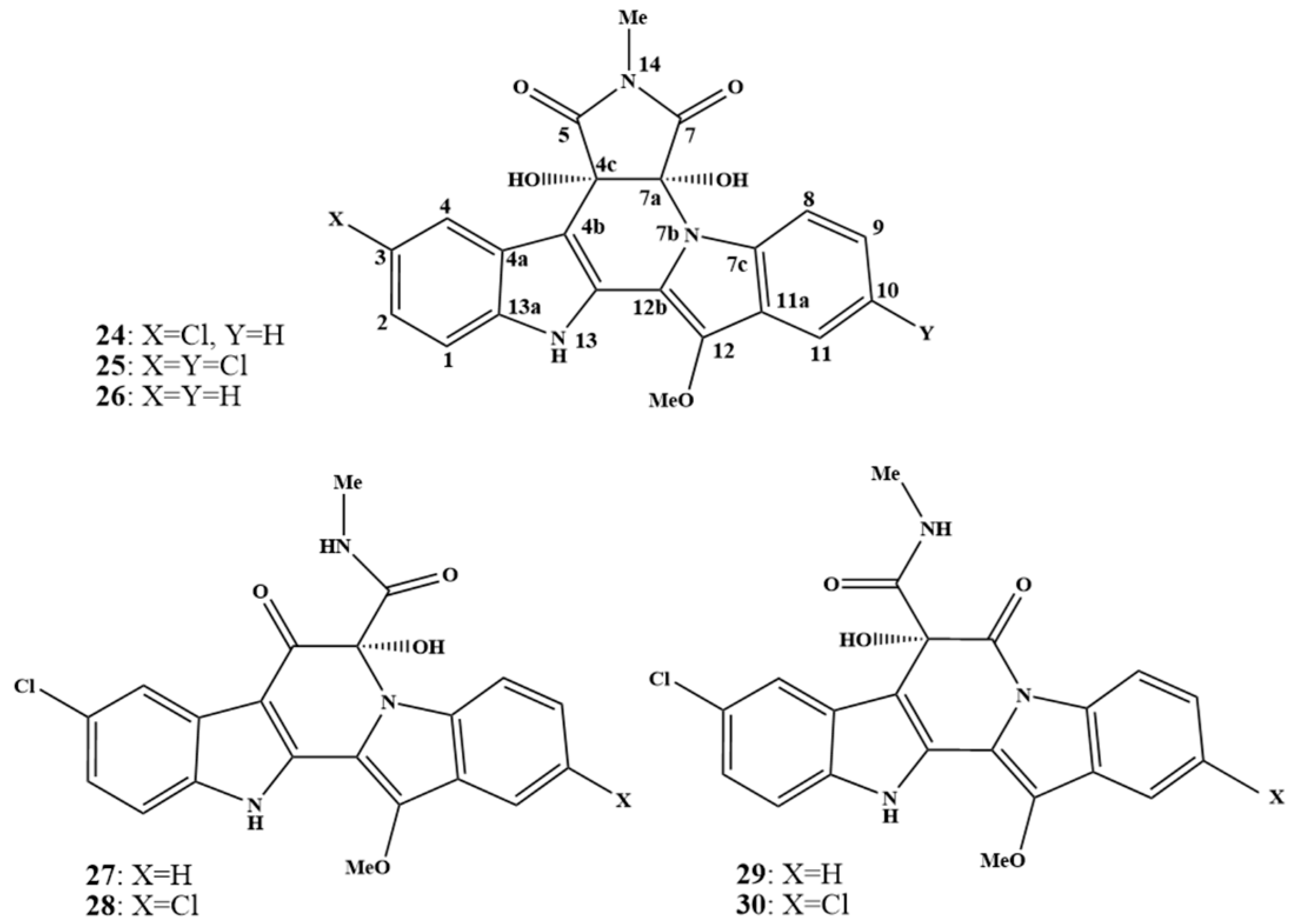

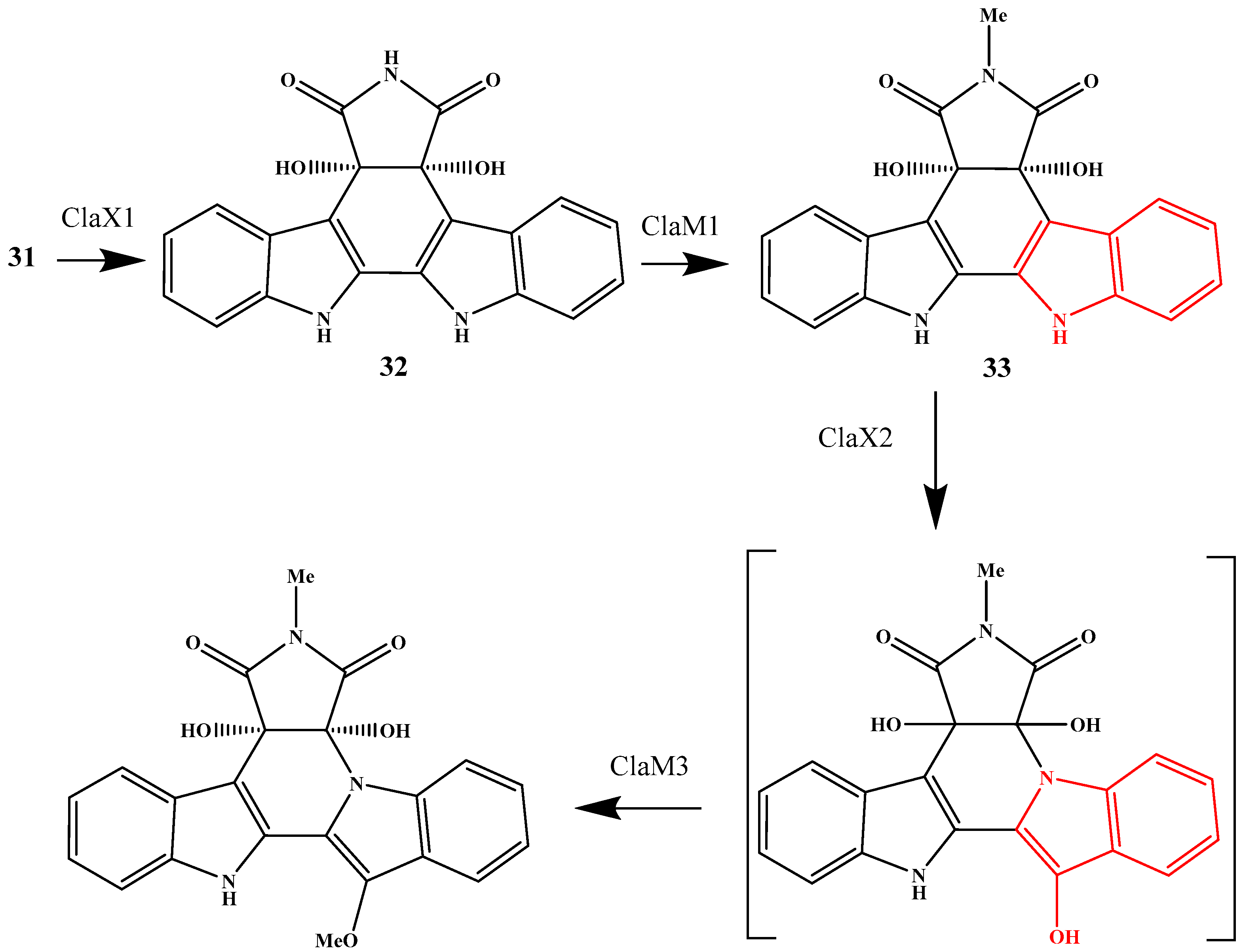

- Williams, D.E.; Davies, J.; Patrick, B.O.; Bottriell, H.; Tarling, T.; Roberge, M.; Andersen, J. Cladoniamides A-G, tryptophan-derived alkaloids produced in culture by Streptomyces uncialis. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

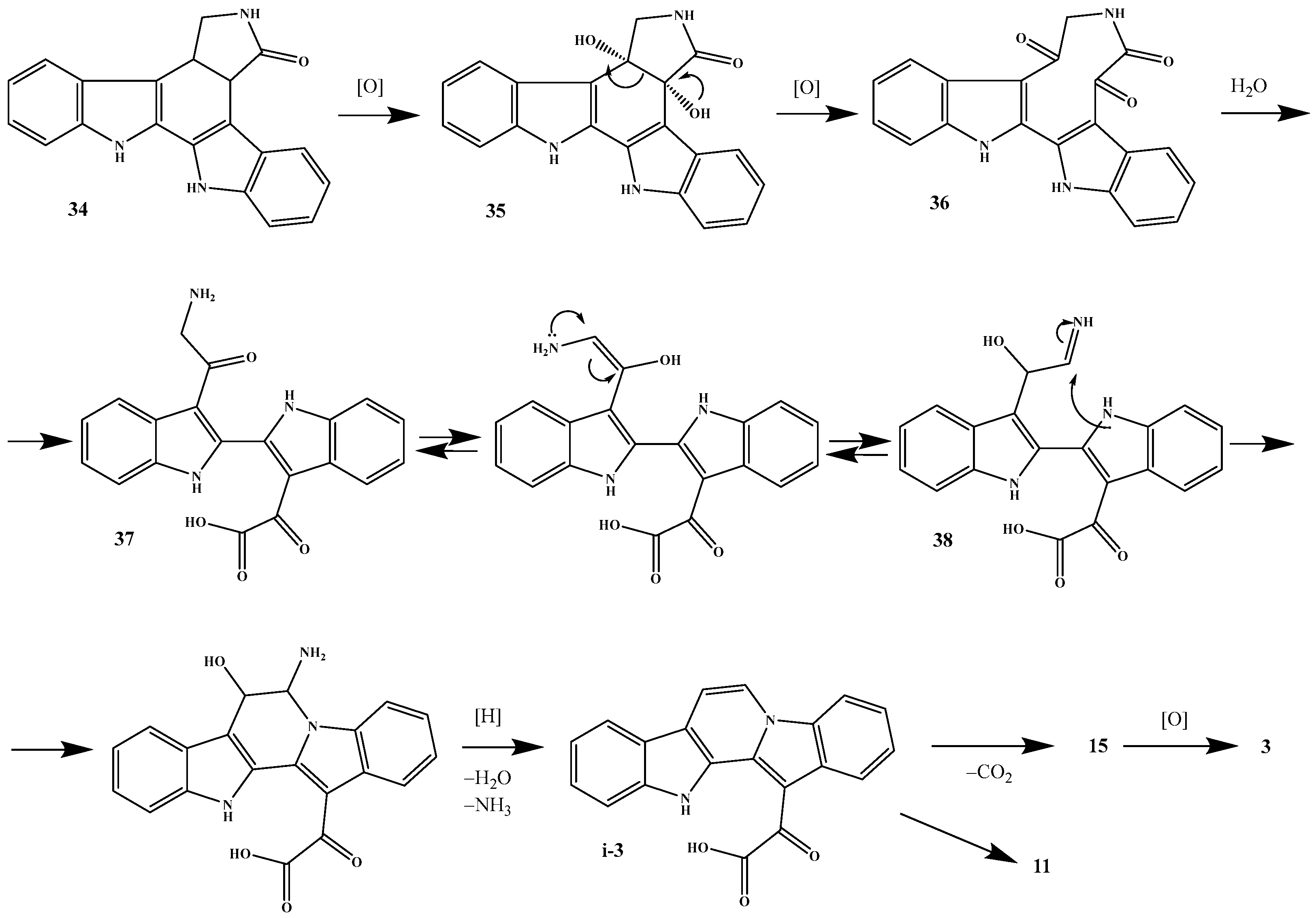

- Du, Y.-L.; Williams, D.E.; Patrick, B.O.; Andersen, R.J.; Ryan, S. Reconstruction of cladoniamide biosynthesis reveals nonenzymatic routes to bisindole diversity. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014, 9, 2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omura, S.; Sasaki, Y.; Iwai, Y.; Takeshima, H. Staurosporine, a potentially important gift from a microorganism. J. Antibiot. 1995, 48, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubbies, M.; Goller, B.; Russmann, E.; Stockinger, H.; Scheuer, W. Complex Ca2+ flux inhibition as primary mechanism of staurosporine-induced impairment of T cell activation. Eur. J. Immunol. 1989, 19, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, J.A.; Claridge, C.; Bush, J.A.; Titus, J.; Bradner, W.T.; Doyle, T.W.; Horan, A.C.; Patel, M. AT2433-A1, AT2433-A2, AT2433-B1, and AT2433-B2 novel antitumor antibiotic compounds produced by Actinomadura melliaura. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation and biological properties. J. Antibiot. 1989, 42, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezaki, M.; Sasaki, T.; Nakazawa, T.; Takeda, U.; Iwata, M.; Watanabe, T.; Koyama, M.; Kai, F.; Shomura, T.; Kojima, M. A new antibiotic SF-2370 produced by Actinomadura. J. Antibiot. 1985, 38, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steglich, W.; Steffan, B.; Kopanski, L.; Eckhardt, G. Indolfarbstoffe aus Fruchtkörpern des Schleimpilzes Arcyria denudata. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1980, 19, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omura, S.; Iwai, Y.; Hirano, A.; Nakagawa, A.; Awaya, J.; Tsuchya, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Masuma, R. A new alkaloid AM-2282 OF Streptomyces origin. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation and preliminary characterization. J. Antibiot. 1977, 30, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonjouklian, R.; Smitka, T.A.; Doolin, L.E.; Molloy, R.M.; Debono, M.; Shaffer, S.A.; Moore, R.E.; Stewart, J.B.; Patterson, G.M.L. Tjipanazoles, new antifungal agents from the blue-green alga Tolypothrix tjipanasensis. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991, 47, 7739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartuche, L.; Reyes-Batlle, M.; Sifaoui, I.; Arberas-Jiménez, I.; Piñero, J.E.; Fernández, J.J.; Lorenzo-Morales, J.; Díaz-Marrero, A.R. Antiamoebic activities of indolocarbazole metabolites isolated from Streptomyces sanyensis cultures. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barth, T.; Bruges, G.; Meiwes, A.; Mogk, S.; Mudogo, C.; Duszenko, M. Staurosporine-induced cell death in Trypanosoma brucei and the role of endonuclease G during apoptosis. Open J. Apoptosis 2014, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knübel, G.; Larsen, L.K.; Moore, R.E.; Levine, I.A.; Patterson, G.M. Totoxic, antiviral indolocarbazoles from a blue-green alga belonging to the Nostocaceae. J. Antibiot. 1990, 43, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, M.J.; Baxter, R.; Bonser, R.W.; Cockerill, S.; Gohil, K.; Parry, N.; Robinson, E.; Randall, R.; Yeates, C.; Snowden, W.; et al. Synthesis of N-alkyl substituted indolocarbazoles as potent inhibitors of human cytomegalovirus replication. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 1993–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, A.; Wilts, H.; Lenhardt, M.; Hahn, M.; Mertens, T. Indolocarbazoles exhibit strong antiviral activity against human cytomegalovirus and are potent inhibitors of the pUL97 protein kinase. Antiviral Res. 2000, 48, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershburg, E.; Hong, K.; Pagano, J.S. Effects of maribavir and selected indolocarbazoles on Epstein-Barr virus protein kinase BGLF4 and on viral lytic replication. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanida, S.; Takizawa, M.; Takahashi, T.; Tsubotani, S.; Harada, S. TAN-999 and TAN-1030A, new indolocarbazole alkaloids with macrophage-activating properties. J. Antibiot. 1989, 42, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Matsuura, N.; Ubukata, M. Indocarbazostatins C and D, new inhibitors of NGF-induced neuronal differentiation in PC12 cells. J. Antibiot. 2004, 57, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuura, N.; Tamehiro, N.; Andoh, T.; Kawashima, A.; Ubukata, M. Indocarbazostatin and indocarbazostatin B, novel inhibitors of NGF-induced neuronal differentiation in PC12 cells. J. Antibiot. 2002, 55, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlpine, J.; Karwowski, J.; Jackson, M.; Mullally, M.; Hochlowski, J.; Premachandran, U.; Burres, N. MLR-52, (4′-demethylamino-4′,5′-dihydroxystaurosporine), a new inhibitor of protein kinase C with immunosuppressive activity. J. Antibiot. 1994, 47, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, S.; Li, H.; Hou, Y.; Cao, H.; Hua, H.; Li, D. Marine-derived lead fascaplysin: Pharmacological activity, total synthesis, and structural modification. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.M.; Stonik, V.A. Physiological activity of fascaplysin—An unusual pigment from marine tropical sponges. Antibiot. Khimioter 1991, 36, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Long, B.H.; Rose, W.C.; Vyas, D.M.; Matson, J.A.; Forenza, S. Discovery of antitumor indolocarbazoles: Rebeccamycin, NSC 655649, and fluoroindolocarbazoles. Curr. Med. Chem. Anticancer Agents 2002, 2, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudhomme, M. Rebeccamycin analogues as anti-cancer agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 38, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, P.; Gaillard, N.; Marminon, C.; Anizon, F.; Dias, N.; Baldeyrou, B.; Bailly, C.; Pierre, A.; Hickman, J.; Pfeiffer, B.; et al. Semi-synthesis, topoisomerase I and kinases inhibitory properties, and antiproliferative activities of new rebeccamycin derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003, 11, 4871–4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreau, P.; Holbeck, S.; Prudhomme, M.; Sausville, E.A. Cytotoxicities of three rebeccamycin derivatives in the National Cancer Institute screening of 60 human tumor cell lines. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2005, 16, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anizon, F.; Moreau, P.; Sancelme, M.; Laine, W.; Bailly, C.; Prudhomme, M. Rebeccamycin analogues bearing amine substituents or other groups on the sugar moiety. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003, 11, 3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojiri, K.; Kondo, H.; Yoshinari, T.; Arakawa, H.; Nakajima, S.; Satoh, F.; Kawamura, K.; Okura, A.; Suda, H.; Okanishi, M. A new antitumor substance BE-13793C, produced by a streptomycete. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation, structure determination and biological activity. J. Antibiot. 1991, 44, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailly, C.; Riou, J.F.; Colson, P.; Houssier, C.; Rodrigues-Pereira, E.; Prudhomme, M. DNA cleavage by topoisomerase I in the presence of indolocarbazole derivatives of rebeccamycin. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staker, B.L.; Feese, M.D.; Cushman, M.; Pommier, Y.; Zembower, D.; Stewart, L.; Burgin, A.B. Structures of three classes of anticancer agents bound to the human topoisomerase I-DNA covalent complex. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.M.; Westbrook, J.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.; Bhat, T.N.; Weissig, H.; Shindyalov, I.N.; Bourne, P.E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehnal, D.; Bittrich, S.; Deshpande, M.; Svobodová, R.; Berka, K.; Bazgier, V.; Velankar, S.; Burley, S.K.; Koča, J.; Rose, A.S. Mol* Viewer: Modern web app for 3D visualization and analysis of large biomolecular structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, E.J.; Chisholm, J.D.; Van Vranken, D.L. Conformational control in the rebeccamycin class of indolocarbazole glycosides. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 5670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facompré, M.; Carrasco, C.; Vezin, H.; Chisholm, J.D.; Yoburn, J.C.; Van Vranken, D.L.; Bailly, C. Indolocarbazole glycosides in inactive conformations. ChemBioChem 2003, 4, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soret, J.; Gabut, M.; Dupon, C.; Kohlhagen, G.; Stévenin, J.; Pommier, Y.; Tazi, J. Altered serine/arginine-rich protein phosphorylation and exonic enhancer-dependent splicing in Mammalian cells lacking topoisomerase I. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 8203–8211. [Google Scholar]

- Labourier, E.; Riou, J.F.; Prudhomme, M.; Carrasco, C.; Bailly, C.; Tazi, J. Poisoning of topoisomerase I by an antitumor indolocarbazole drug: Stabilization of topoisomerase I-DNA covalent complexes and specific inhibition of the protein kinase activity. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pilch, B.; Allemand, E.; Facompré, M.; Bailly, C.; Riou, J.F.; Soret, J.; Tazi, J. Specific inhibition of serine- and arginine-rich splicing factors phosphorylation, spliceosome assembly, and splicing by the antitumor drug NB-506. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 6876. [Google Scholar]

- Tamaoki, T.; Nomoto, H.; Takahashi, I.; Kato, Y.; Morimoto, M.; Tomita, F. Staurosporine, a potent inhibitor of phospholipid/Ca++dependent protein kinase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1986, 135, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komander, D.; Kular, G.S.; Bain, J.; Elliott, M.; Alessi, D.R.; Van Aalten, D.M. Structural basis for UCN-01 (7-hydroxystaurosporine) specificity and PDK1 (3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1) inhibition. Biochem. J. 2003, 375, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastassiadis, T.; Deacon, S.W.; Devarajan, K.; Ma, H.; Peterson, J.R. Comprehensive assay of kinase catalytic activity reveals features of kinase inhibitor selectivity. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conseil, G.; Perez-Victoria, J.M.; Jault, J.M.; Gamarro, F.; Goffeau, A.; Hofmann, J.; Di Pietro, A. Protein kinase C effectors bind to multidrug ABC transporters and inhibit their activity. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robey, R.W.; Shukla, S.; Steadman, K.; Obrzut, T.; Finley, E.M.; Ambudkar, S.V.; Bates, S.E. Inhibition of ABCG2-mediated transport by protein kinase inhibitors with a bisindolylmaleimide or indolocarbazole structure. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007, 6, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gingrich, D.E.; Yang, S.X.; Gessner, G.W.; Angeles, T.S.; Hudkins, R.L. Synthesis, modeling, and in vitro activity of (3′S)-epi-K-252a analogues. Elucidating the stereochemical requirements of the 3′-sugar alcohol on trkA tyrosine kinase activity. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinschroth, J.; Hartenstein, J.; Rudolph, C.; Schachtele, C. Novel indolocarbazole protein kinase c inhibitors with improved biochemical and physicochemical properties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1995, 5, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.C.; Derian, C.K.; McComsey, D.F.; White, K.B.; Ye, H.; Hecker, L.R.; Li, J.; Addo, M.F.; Croll, D.; Eckardt, A.J.; et al. Novel indolylindazolylmaleimides as inhibitors of protein kinase C-β: Synthesis, biological activity, and cardiovascular safety. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Martinez, C.; Shih, C.; Zhu, G.; Li, T.; Brooks, H.B.; Patel, B.K.; Schultz, R.M.; DeHahn, T.B.; Spencer, C.D.; Watkins, S.A.; et al. Studies on cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors: Indolo-[2,3-a]pyrrolo [3,4-c]carbazoles versus bis-indolylmaleimides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003, 13, 3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Conner, S.E.; Zhou, X.; Chan, H.K.; Shih, C.; Engler, T.A.; Al-Awar, R.S.; Brooks, H.B.; Watkins, S.A.; Spencer, C.D.; et al. Synthesis of 1,7-annulated indoles and their applications in the studies of cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, M.M.; Sullivan, K.A.; Grutsch, J.L.; Winneroski, L.L.; Shih, C.; Sanchez-Martinez, C.; Cooper, J.T. Synthesis of indolo [2,3-a]carbazole glycoside analogs of rebeccamycin: Inhibitors of cyclin D1-CDK4. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-awar, R.S.; Ray, J.E.; Hecker, K.A.; Joseph, S.; Huang, J.; Shih, C.; Brooks, H.B.; Spencer, C.D.; Watkins, S.A.; Schultz, R.M.; et al. Preparation of novel aza-1,7-annulated indoles and their conversion to potent indolocarbazole kinase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, G.H.; Prouty, C.; DeAngelis, A.; Shen, L.; O’Neill, D.J.; Shah, C.; Connolly, P.J.; Murray, W.V.; Conway, B.R.; Cheung, P.; et al. Synthesis and discovery of macrocyclic polyoxygenated bis-7-azaindolylmaleimides as a novel series of potent and highly selective glycogen synthase kinase-3β inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 46, 4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gingrich, D.E.; Reddy, D.R.; Iqbal, M.A.; Singh, J.; Aimone, L.D.; Angeles, T.S.; Albom, M.; Yang, S.; Ator, M.A.; Meyer, S.L.; et al. A new class of potent vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors: Structure-activity relationships for a series of 9-alkoxymethyl-12-(3-hydroxypropyl)indeno [2,1-a]pyrrolo [3,4-c]carbazole-5-ones and the identification of CEP-5214 and its dimethylglycine ester prodrug clinical candidate CEP-7055. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 46, 5375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakata, C.; Kaneko, M.; Gessner, G.; Angeles, T.S.; Ator, M.A.; O’Kane, T.M.; McKenna, B.A.; Thomas, B.A.; Mathiasen, J.R.; Saporito, M.S.; et al. Mixed lineage kinase activity of indolocarbazole analogues. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002, 12, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Bower, M.J.; McDevitt, P.J.; Zhao, H.; Davis, S.T.; Johanson, K.O.; Green, S.M.; Concha, N.O.; Zhou, B.B. Structural basis for Chk1 inhibition by UCN-01. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 29, 46609-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, R.; Muller, L.; Furet, P.; Schoepfer, J.; Stephan, C.; Zumstein-Mecker, S.; Fretz, H.; Chaudhuri, B. Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (Cdk4) by fascaplysin, a marine natural product. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 275, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörmann, A.; Chaudhuri, B.; Fretz, H. DNA binding properties of the marine sponge pigment fascaplysin. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. 2001, 9, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubry, C.; Jenkins, P.R.; Mahale, S.; Chaudhuri, B.; Maréchal, J.D.; Sutcliffe, M.J. New fascaplysin-based CDK4-specific inhibitors: Design, synthesis and biological activity. Chem. Commun. 2004, 35, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubry, C.; Wilson, A.J.; Jenkins, P.R.; Mahale, S.; Chaudhuri, B.; Maréchal, J.D.; Sutcliffe, M.J. Design, synthesis and biological activity of new CDK4-specific inhibitors, based on fascaplysin. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006, 4, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahale, S.; Aubry, C.; Wilson, A.J.; Jenkins, P.R.; Maréchal, J.D.; Sutcliffe, M.J.; Chaudhuri, B. CA224, a non-planar analogue of fascaplysin, inhibits Cdk4 but not Cdk2 and arrests cells at G0/G1 inhibiting pRB phosphorylation. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.D.; Wilson, A.J.; Emmerson, D.P.G.; Jenkins, P.R.; Mahale, S.; Chaudhuri, B. Synthesis, crystal structure and biological activity of β-carboline based selective CDK4-cyclin D1 inhibitors. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006, 4, 4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, P.R.; Wilson, J.; Emmerson, D.; Garcia, M.D.; Smith, M.R.; Gray, S.J.; Britton, R.G.; Mahale, S.; Chaudhuri, B. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of new tryptamine and tetrahydro-β-carboline-based selective inhibitors of CDK4. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 7728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubry, C.; Wilson, A.J.; Emmerson, D.; Murphy, E.; Chan, Y.Y.; Dickens, M.P.; García, M.D.; Jenkins, P.R.; Mahale, S.; Chaudhuri, B. Fascaplysin-inspired diindolyls as selective inhibitors of CDK4/cyclin D1. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 6073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Yan, X.J.; Chen, H.M. Fascaplysin, a selective CDK4 inhibitor, exhibit anti-angiogenic activity in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2007, 59, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.L.; Zheng, Y.L.; Chen, H.M.; Yan, X.J.; Wang, F.; Xu, W.F. Antiproliferation of human cervical cancer HeLa cell line by fascaplysin through apoptosis induction. Yao Xue Xue Bao 2009, 44, 980. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.L.; Lu, X.L.; Lin, J.; Chen, H.M.; Yan, X.J.; Wang, F.; Xu, W.F. Direct effects of fascaplysin on human umbilical vein endothelial cells attributing the anti-angiogenesis activity. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2010, 64, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafiq, M.I.; Steinbrecher, T.; Schmid, R. Fascaplysin as a specific inhibitor for CDK4: Insights from molecular modelling. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, T.I.; Lee, Y.M.; Nam, T.J.; Ko, Y.S.; Mah, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Reddy, R.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Hong, S.; et al. Fascaplysin exerts anti-cancer effects through the downregulation of survivin and HIF-1α and inhibition of VEGFR2 and TRKA. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyshlovoy, S.A.; Mansour, W.Y.; Ramm, N.A.; Hauschild, J.; Zhidkov, M.E.; Kriegs, M.; Zielinski, A.; Hoffer, K.; Busenbender, T.; Glumakova, K.A.; et al. Synthesis and new DNA targeting activity of 6- and 7-tert-butylfascaplysins. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, G. Cytotoxic effects of fascaplysin against small cell lung cancer cell lines. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Guru, S.K.; Pathania, A.S.; Manda, S.; Kumar, A.; Bharate, S.B.; Vishwakarma, R.A.; Malik, F.; Bhushan, S. Fascaplysin induces caspase mediated crosstalk between apoptosis and autophagy through the inhibition of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling cascade in human leukemia HL-60 cells. J. Cell Biochem. 2015, 116, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastrzebski, K.; Hannan, K.M.; Tchoubrieva, E.B.; Hannan, R.D.; Pearson, R.B. Coordinate regulation of ribosome biogenesis and function by the ribosomal protein S6 kinase, a key mediator of mTOR function. Growth Factors 2007, 25, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, T.I.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, S.; Nam, T.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, B.M.; Yim, W.J.; Lim, J.H. Fascaplysin sensitizes anti-cancer effects of drugs targeting AKT and AMPK. Molecules 2018, 23, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, N.; Mu, X.; Lv, X.; Wang, L.; Li, N.; Gong, Y. Autophagy represses fascaplysin-induced apoptosis and angiogenesis inhibition via ROS and p8 in vascular endothelia cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 114, 108866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, T.A.; Milan-Lobo, L.; Che, T.; Ferwerda, M.; Lambo, E.; McIntosh, N.L.; Li, F.; He, L.; Lorig-Roach, N.; Crews, P.; et al. Identification of the first marine-derived opioid receptor “balanced” agonist with a signaling profile that resembles the endorphins. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017, 8, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharate, S.B.; Manda, S.; Joshi, P.; Singh, B.; Vishwakarma, R.A. Total synthesis and anti-cholinesterase activity of marine-derived bis-indole alkaloid fascaplysin. Med. Chem. Comm. 2012, 3, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manda, S.; Sharma, S.; Wani, A.; Joshi, P.; Kumar, V.; Guru, S.K.; Bharate, S.S.; Bhushan, S.; Vishwakarma, R.; Kumar, A.; et al. Discovery of a marine-derived bis-indole alkaloid fascaplysin, as a new class of potent P-glycoprotein inducer and establishment of its structure-activity relationship. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 107, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, J.A.; Long, B.H.; Catino, J.J.; Bradner, W.T.; Tomita, K. Production and biological activity of rebeccamycin, a novel antitumor agent. J. Antibiot. 1987, 40, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, I.; Kobayashi, E.; Asano, K.; Yoshida, M.; Nakano, H. UCN-01, a selective inhibitor of protein kinase C from Streptomyces. J. Antibiot. 1987, 40, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, B.; Nakeff, A.; Tenney, K.; Crews, P.; Gunatilaka, L.; Valeriote, F. A new paradigm for the development of anticancer agents from natural products. J. Exp. Ther. Oncol. 2006, 5, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Chen, H.; Lu, X.; Wang, F.; Xu, W.; Jin, H.; Zhu, P. Fascaplysin exert anti-tumor effects through apoptotic and anti-angiogenesis pathways in sarcoma mice model. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 43, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mischitelli, M.; Jemaà, M.; Almasry, M.; Faggio, C.; Lang, F. Triggering of suicidal erythrocyte death by fascaplysin. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 39, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampofo, E.; Später, T.; Müller, I.; Eichler, H.; Menger, M.D.; Laschke, M.W. The marine-derived kinase inhibitor fascaplysin exerts anti-thrombotic activity. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 6774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Zhang, M.; He, M.; Fang, B.; Bao, X.; Yan, X.; Liang, H.; Wang, H. Determination of fascaplysin in rat plasma with ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC–MS/MS): Application to a pharmacokinetic study. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 171, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, Y.; Sun, X.; Shi, X.; Liang, H.; Chen, X.; Cui, W.; Fan, Y.; Ma, J.; Wang, H. Pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution, and excretion of 9-methylfascaplysin, a potential anti-Alzheimer’s disease agent. Electrophoresis 2025, 46, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrushaid, S.; Sayre, C.L.; Yáñez, J.A.; Forrest, M.L.; Senadheera, S.N.; Burczynski, F.J.; Löbenberg, R.; Davies, N.M. Pharmacokinetic and toxicodynamic characterization of a novel doxorubicin derivative. Pharmaceutics 2017, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurley, L.R.; Umbarger, K.O.; Kim, J.M.; Bradbury, E.M.; Lehnert, B.E. High-performance liquid chromatographic analysis of staurosporine in vivo. Its translocation and pharmacokinetics in rats. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl. 1998, 712, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuse, E.; Kuwabara, T.; Sparreboom, A.; Sausville, E.A.; Figg, W.D. Review of UCN-01 development: A lesson in the importance of clinical pharmacology. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2005, 45, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, J.S.; Percival, M.E. Midostaurin for the treatment of adult patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia that is FLT3 mutation-positive. Drugs Today 2017, 53, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.S. Midostaurin: First Global Approval. Drugs 2017, 77, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, R.M.; Manley, P.W.; Larson, R.A.; Capdeville, R. Midostaurin: Its odyssey from discovery to approval for treating acute myeloid leukemia and advanced systemic mastocytosis. Blood Adv. 2018, 2, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, M.; Allebach, J.; Tse, K.-F.; Zheng, R.; Baldwin, B.R.; Smith, B.D.; Jones-Bolin, S.; Ruggeri, B.; Dionne, C.; Small, D. A FLT3-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor is cytotoxic to leukemia cells in vitro and in vivo. Blood 2002, 99, 3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hexner, E.O.; Serdikoff, C.; Jan, M.; Swider, C.R.; Robinson, C.; Yang, S.; Angeles, T.; Emerson, S.G.; Carroll, M.; Ruggeri, B.; et al. Lestaurtinib (CEP701) is a JAK2 inhibitor that suppresses JAK2/STAT5 signaling and the proliferation of primary erythroid cells from patients with myeloproliferative disorders. Blood 2008, 111, 5663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.D.; Levis, M.; Beran, M.; Giles, F.; Kantarjian, H.; Berg, K.; Murphy, K.M.; Dauses, T.; Allebach, J.; Small, D. Single-agent CEP-701, a novel FLT3 inhibitor, shows biologic and clinical activity in patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2004, 103, 3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, M.; Ravandi, F.; Wang, E.S.; Baer, M.R.; Perl, A.; Coutre, S.; Erba, H.; Stuart, R.K.; Baccarani, M.; Cripe, L.D.; et al. Results from a randomized trial of salvage chemotherapy followed by lestaurtinib for patients with FLT3 mutant AML in first relapse. Blood 2011, 117, 3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapper, S.; Russell, N.; Gilkes, A.; Hills, R.K.; Gale, R.E.; Cavenagh, J.D.; Jones, G.; Kjeldsen, L.; Grunwald, M.R.; Thomas, I.; et al. A randomized assessment of adding the kinase inhibitor lestaurtinib to first-line chemotherapy for FLT3-mutated AML. Blood 2017, 129, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hexner, E.O.; Mascarenhas, J.; Prchal, J.; Roboz, G.J.; Baer, M.R.; Ritchie, E.K.; Leibowitz, D.; Demakos, E.P.; Miller, C.; Siuty, J.; et al. Phase I dose escalation study of lestaurtinib in patients with myelofibrosis. Leuk. Lymphoma 2015, 56, 2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson Study Group. The safety and tolerability of a mixed lineage kinase inhibitor (CEP-1347) in PD. Neurology 2004, 62, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, T.H.; Brotchie, J.M. Drugs in development for Parkinson’s disease: An update. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2006, 7, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko, T.; Wong, H.; Utzig, J.; Schurig, J.; Doyle, T. Water soluble derivatives of rebeccamycin. J. Antibiot. 1990, 43, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Vaishampayan, U.; Heilbrun, L.K.; Jain, V.; LoRusso, P.M.; Ivy, P.; Flaherty, L. A phase II study of rebeccamycin analog (NSC-655649) in metastatic renal cell cancer. Investig. N. Drugs 2003, 21, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burstein, H.; Overmoyer, B.; Gelman, R.; Silverman, P.; Savoie, J.; Clarke, K.; Dumadag, L.; Younger, J.; Ivy, P.; Winer, E.P. Rebeccamycin analog for refractory breast cancer: A randomized phase II trial of dosing schedules. Investig. N. Drugs 2007, 25, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langevin, A.-M.; Bernstein, M.; Kuhn, J.G.; Blaney, S.M.; Ivy, P.; Sun, J.; Chen, Z.; Adamson, P.C. A phase ii trial of rebeccamycin analogue (NSC #655649) in children with solid tumors: A children’s oncology group study. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2008, 50, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwandt, A.; Mekhail, T.; Halmos, B.; O’Brien, T.; Ma, P.C.; Fu, P.; Ivy, P.; Dowlati, A. Phase-II trial of rebeccamycin analog, a dual topoisomerase-I and -II inhibitor, in relapsed “sensitive” small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2012, 7, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowlati, A.; Chapman, R.; Subbiah, S.; Fu, P.; Ness, A.; Cortas, T.; Patrick, L.; Reynolds, S.; Xu, N.; Levitan, N.; et al. Randomized phase II trial of different schedules of administration of rebeccamycin analogue as second line therapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Investig. N. Drugs 2005, 23, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshinari, T.; Matsumoto, M.; Arakawa, H.; Okada, H.; Noguchi, K.; Suda, H.; Okura, A.; Nishimura, S. Novel antitumor indolocarbazole compound 6-N-formylamino-12,13-dihydro-1,11-dihydroxy-13-(β-D-glucopyranosyl)-5H-indolo [2,3-a]pyrrolo [3,4-c]carbazole-5,7(6H)-dione (NB-506): Induction of topoisomerase I-mediated DNA cleavage and mechanisms of cell line-selective cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 1995, 55, 1310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arakawa, H.; Iguchi, T.; Morita, M.; Yoshinari, T.; Kojiri, K.; Suda, H.; Okura, A.; Nishimura, S. Novel indolocarbazole compound 6-N-formylamino-12,13-dihydro-1,11-dihydroxy- 13-(β-D-glucopyranosyl)-5H-indolo [2,3-a]pyrrolo-[3,4-c]carbazole-5,7(6H)-dione (NB-506): Its potent antitumor activities in mice. Cancer Res. 1995, 55, 1316. [Google Scholar]

- Ohkubo, M.; Nishimura, T.; Honma, T.; Nishimura, I.; Ito, S.; Yoshinari, T.; Suda, H.A.; Morishima, H.; Nishimura, S. Synthesis and biological activities of NB-506 analogues: Effects of the positions of two hydroxyl groups at the indole rings. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999, 9, 3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, M.W.; Diasio, R.B. Edotecarin: A novel topoisomerase I inhibitor. Clin. Color. Cancer 2005, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gribble, G.W.; Pelcman, B. Total syntheses of the marine sponge pigments fascaplysin and homofascaplysin B and C. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocca, P.; Marsais, F.; Godard, A.; Quéguiner, G. A short synthesis of the antimicrobial marine sponge pigment fascaplysin. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 34, 7917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, P.; Fresneda, P.M.; García-Zafra, S.; Almendros, P. Iminophosphorane-mediated syntheses of the fascaplysin alkaloid of marine origin and nitramarine. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 8851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radchenko, O.S.; Novikov, V.L.; Elyakov, G.B. A simple and practical approach to the synthesis of the marine sponge pigment fascaplysin and related compounds. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 5339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldmann, H.; Eberhardt, L.; Wittstein, K.; Kumar, K. Silver catalyzed cascade synthesis of alkaloid ring systems: Concise total synthesis of fascaplysin, homofascaplysin C and analogues. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhidkov, M.E.; Baranova, O.V.; Kravchenko, N.S.; Dubovitskii, S.V. A new method for the synthesis of the marine alkaloid fascaplysin. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 6498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhidkov, M.E.; Kaminskii, V.A. A new method for the synthesis of the marine alkaloid fascaplysin based on the micro-wave-assisted Minisci reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.-P.; Liu, M.-C.; Cai, Q.; Jia, F.-C.; Wu, A.-X. A cascade coupling strategy for one-pot total synthesis of β-carboline and isoquinoline-containing natural products and derivatives. Chem. A Eur. J. 2013, 19, 10132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhidkov, M.E.; Kantemirov, A.V.; Koisevnikov, A.V.; Andin, A.N.; Kuzmich, A.S. Syntheses of the marine alkaloids 6-oxofascaplysin, fascaplysin and their derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palani, V.; Perea, M.A.; Gardner, K.E.; Sarpong, R. A pyrone remodeling strategy to access diverse heterocycles: Application to the synthesis of fascaplysin natural products. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryapkin, O.A.; Kantemirov, A.V.; Dyshlovoy, S.A.; Prassolov, V.S.; Spirin, P.V.; von Amsberg, G.; Sidorova, M.A.; Zhidkov, M.E. A new mild method for synthesis of marine alkaloid fascaplysin and its therapeutically promising derivatives. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Guru, S.K.; Manda, S.; Kumar, A.; Mintoo, M.J.; Prasad, V.D.; Sharma, P.R.; Mondhe, D.M.; Bharate, S.B.; Bhushan, S. A marine sponge alkaloid derivative 4-chloro fascaplysin inhibits tumor growth and VEGF mediated angiogenesis by disrupting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling cascade. Chem. Interact. 2017, 275, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Qiu, H.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, P.; Liang, W.; Yang, M.; Mou, C.; Lin, M.; He, M.; Xiao, X.; et al. Fascaplysin derivatives are potent multitarget agents against Alzheimer’s disease: In vitro and in vivo evidence. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Liu, F.; Sang, J.; Lin, M.; Lin, M.; Ma, J.; Xiao, X.; Yan, S.; Naman, C.B.; Wang, N.; et al. 9-Methylfascaplysin is a more potent Aβ aggregation inhibitor than the marine-derived alkaloid, fascaplysin, and produces nanomolar neuroprotective effects in SH-SY5Y cells. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Qiu, H.; Yang, N.; Xie, H.; Liang, W.; Lin, J.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, N.; Tan, X.; et al. Fascaplysin derivatives binding to DNA via unique cationic five-ring coplanar backbone showed potent antimicrobial/antibiofilm activity against MRSA in vitro and in vivo. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 230, 114099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, Y.; Liang, W.; Wang, W.; Jiang, X.; Jiang, M.; Wang, X.; Cui, W.; Li, Y.; et al. Design and synthesis of fascaplysin derivatives as inhibitors of FtsZ with potent antibacterial activity and mechanistic study. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 254, 115348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lock, R.L.; Harry, E.J. Cell-division inhibitors: New insights for future antibiotics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silber, N.; de Opitz, C.L.M.; Mayer, C.; Sass, P. Cell division protein FtsZ: From structure and mechanism to antibiotic target. Future Microbiol. 2020, 15, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haydon, D.J.; Stokes, N.R.; Ure, R.; Galbraith, G.; Bennett, J.M.; Brown, D.R.; Baker, P.J.; Barynin, V.V.; Rice, D.W.; Sedelnikova, S.E.; et al. An inhibitor of FtsZ with potent and selective anti-staphylococcal activity. Science 2008, 321, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisson, A.W.; Hsu, Y.P.; Squyres, G.R.; Kuru, E.; Wu, F.B.; Jukes, C.; Sun, Y.J.; Dekker, C.; Holden, S.; Van Nieuwenhze, M.S.; et al. Treadmilling by FtsZ filaments drives peptidoglycan synthesis and bacterial cell division. Science 2017, 355, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Cao, X.; Qiu, H.; Liang, W.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, W.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Han, B.; et al. Rational molecular design converting fascaplysin derivatives to potent broad-spectrum inhibitors against bacterial pathogens via targeting FtsZ. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 270, 116347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhidkov, M.E.; Sidorova, M.A.; Smirnova, P.A.; Tryapkin, O.A.; Kachanov, A.V.; Kantemirov, A.V.; Dezhenkova, L.G.; Grammatikova, N.E.; Isakova, E.B.; Shchekotikhin, A.E.; et al. Comparative evaluation of the antibacterial and antitumor activities of 9-phenylfascaplysin and its analogs. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhidkov, M.E.; Smirnova, P.A.; Grammatikova, N.E.; Isakova, E.B.; Shchekotikhin, A.E.; Styshova, O.N.; Klimovich, A.A.; Popov, A.M. Comparative evaluation of the antibacterial and antitumor activities of marine alkaloid 3,10-dibromofascaplysin. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhidkov, M.E.; Smirnova, P.A.; Tryapkin, O.A.; Kantemirov, A.V.; Khudyakova, Y.V.; Malyarenko, O.S.; Ermakova, S.P.; Grigorchuk, V.P.; Kaune, M.; Von Amsberg, G.; et al. Total syntheses and preliminary biological evaluation of brominated fascaplysin and reticulatine alkaloids and their analogues. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhidkov, M.E.; Kaune, M.; Kantemirov, A.V.; Smirnova, P.A.; Spirin, P.V.; Sidorova, M.A.; Stadnik, S.A.; Shyrokova, E.Y.; Kaluzhny, D.N.; Tryapkin, O.A.; et al. Study of structure–activity relationships of the marine alkaloid fascaplysin and its derivatives as potent anticancer agents. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spirin, P.; Shyrokova, E.; Lebedev, T.; Vagapova, E.; Smirnova, P.; Kantemirov, A.; Dyshlovoy, S.A.; von Amsberg, G.; Zhidkov, M.; Prassolov, V. Cytotoxic marine alkaloid 3,10-dibromofascaplysin induces apoptosis and synergizes with cytarabine resulting in leukemia cell death. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyshlovoy, S.A.; Kaune, M.; Hauschild, J.; Kriegs, M.; Hoffer, K.; Busenbender, T.; Smirnova, P.A.; Zhidkov, M.E.; Poverennaya, E.V.; Oh-Hohenhorst, S.J.; et al. Efficacy and mechanism of action of marine alkaloid 3,10-dibromofascaplysin in drug-resistant prostate cancer cells. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Peng, R.; Min, Q.; Hui, S.; Chen, X.; Yang, G.; Qin, S. Bisindole natural products: A vital source for the development of new anticancer drugs. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 243, 114748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, J. Diverse roles of microbial indole compounds in eukaryotic systems. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2021, 96, 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clift, D.; McEwan, W.A.; Labzin, L.I.; Konieczny, V.; Mogessie, B.; James, L.C.; Schuh, M. A method for the acute and rapid degradation of endogenous proteins. Cell 2017, 171, 1692–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pharmacokinetic Parameter | Dox, i.v. | Dox, Oral | Fas, i.v. | Fas, Oral | 40, i.v. | 40, Oral |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose, mg/kg | 10 | 10 | 3 | 15 | 5 | 30 |

| Cmax, µg/L | 24,700 ± 14,200 | 90 ± 10 | 413.6 ± 39.5 | 65.2 ± 13.1 | 1711.7 ± 941.8 | 193.4 ± 83.5 |

| Clast, µg/L | 120 ± 30 | 80 ± 10 | — | — | 12.6 ± 1.0 | 35.2 ± 9.4 |

| Tmax, h | — | — | 0.083 | 0.25 | 0.06 ± 0.05 | 2.7 ± 2.9 |

| MRT0–t, h | — | — | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 9.3 ± 0.3 | 3.9 ± 0.8 | 9.8 ± 0.4 |

| MRT0–∞, h | — | — | 9.7 ± 3.8 | 23.3 ± 9.2 | 5.6 ± 1.7 | 19.9 ± 10.0 |

| kel, 1/h | 0.16 ± 0.02 | — | — | — | 0.1 ± 0.06 | 0.06 ± 0.02 |

| T1/2, h | 4.69 ± 0.8 | — | — | — | 6.8 ± 3.4 | 13.4 ± 7.4 |

| AUC0–t, µg·h/L | 3970 ± 700 | 330 ± 40 | 359.5 ± 15.4 | 358.0 ± 81.9 | 2321.8 ± 613.5 | 1960.8 ± 297.9 |

| AUC0–∞, µg·h/L | 4790 ± 1830 | — | 412.3 ± 43.6 | 561.5 ± 124.3 | 2442.4 ± 619.0 | 2685.0 ± 535.1 |

| Vd, L/kg | 6.35 ± 2.11 | — | 870.6 | 118.3 ± 50.4 | 21.5908 ± 15.1092 | 209.7831 ± 81.1215 |

| CLtotal, L/h/kg | 2.63 ± 0.39 | — | 36.7 | 6.2 ± 3.2 | 2.1724 ± 0.6013 | 11.51646 ± 2.1548 |

| F, % | — | 8.57 ± 0.71 | — | 27.2 ± 4.7 | — | 18.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhidkov, M.E.; Popov, A.M.; Soldatkina, O.A.; Tryapkin, O.A.; Kharchenko, L.N. Can Fascaplysins Be Considered Analogs of Indolo[2,3-a]pyrrolo[3,4-c]carbazoles? Comparison of Biosynthesis, Biological Activity and Therapeutic Potential. Mar. Drugs 2026, 24, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010018

Zhidkov ME, Popov AM, Soldatkina OA, Tryapkin OA, Kharchenko LN. Can Fascaplysins Be Considered Analogs of Indolo[2,3-a]pyrrolo[3,4-c]carbazoles? Comparison of Biosynthesis, Biological Activity and Therapeutic Potential. Marine Drugs. 2026; 24(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhidkov, Maxim E., Aleksandr M. Popov, Olga A. Soldatkina, Oleg A. Tryapkin, and Lyubov N. Kharchenko. 2026. "Can Fascaplysins Be Considered Analogs of Indolo[2,3-a]pyrrolo[3,4-c]carbazoles? Comparison of Biosynthesis, Biological Activity and Therapeutic Potential" Marine Drugs 24, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010018

APA StyleZhidkov, M. E., Popov, A. M., Soldatkina, O. A., Tryapkin, O. A., & Kharchenko, L. N. (2026). Can Fascaplysins Be Considered Analogs of Indolo[2,3-a]pyrrolo[3,4-c]carbazoles? Comparison of Biosynthesis, Biological Activity and Therapeutic Potential. Marine Drugs, 24(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010018