1. Introduction

The unique ecosystems of deep-sea cold seep environments, characterized by methane-rich fluid emissions and unusual sulfur redox reactions, drive the microorganisms in these habitats to evolve unique metabolic pathways, which enable them to biosynthesize novel and bioactive natural products [

1,

2]. The identification of antifungal lipopeptide biosurfactants (surfactin CS30-1 and CS30-2) in the cold-seep derived

Bacillus sp. CS30 has prompted increasing research on natural product discovery from deep-sea cold seep microorganisms [

3]. Five new indole diketopiperazines, which displayed potent activity against the aquatic pathogen

Vibrio harveyi (MICs =8–16 μg/mL), were isolated from deep-sea cold-seep-derived fungus

Aspergillus chevalieri CS-122 [

4]. Four unusual phenylhydrazone alkaloids (talarohydrazones A–D) were discovered from the deep-sea cold-seep-derived fungus

Talaromyces amestolkiae HDN21-0307, among which talarohydrazone A exhibited cytotoxic activity against NCI-H446 cells (IC

50 = 4.1 μM) as well as antibacterial activity against

Staphylococcus aureus (MIC = 32 μg/mL) [

5]. Thus, cold-seep-derived microorganisms have emerged as an important source for bioactive secondary metabolite discovery.

Halomonas spp., which are mainly found in saline environments, such as salt lakes, marshes and oceans, have attracted much attention due to their ability to grow rapidly in saline environments [

6]. They have been developed to be effective chassis for producing various biochemicals, including bioplastics (PolyHydroxyButyrate, PHB), biopigments (β-carotene and lycopene), biofuels (propane and mandelate), amino acids and their derivatives (threonine, lysine, ectoine and cadaverine) [

7].

Halomonas species can act as rhizobial symbionts that promote plant growth by producing plant growth hormone indole-3-acetic acid [

8]. Noticeably, a few bioactive natural products have also been discovered from

Halomonas spp. For example, three new aminophenoxazinones were isolated from marine

Halomonas sp. via anthranilic acid feeding, which displayed antibacterial activity against

Bacillus subtilis and

S. aureus [

9]; four new lipid siderophores (potashchelins A–D) were identified from

Halomonas sp. MG34, and potashchelins A and D displayed inhibitory against

B. subtilis CPCC 100029 [

10]. Several reports on microbial diversity indicated that

Halomonas is widely distributed in the cold-seep ecosystem [

11], but the secondary metabolites of cold-seep-derived

Halomonas strains remain underexploited.

Indole is a versatile signaling molecule that plays an important role in bacterial physiology, pathogenesis, animal behavior and human diseases [

12]. Indole oligomers, which are widely found in plants, animals and microbes, exhibit potent bioactivities and high application values [

13,

14]. The notable oligoindole 3,3′-bisindolylmethane (DIM), which was first discovered from cruciferous vegetables, has been marketed as a nutraceutical as it prevents cancer and shows synergies with paclitaxel [

15]. Indirubin, an indole dimer derived from plant cells, is currently used as a drug to treat chromic granulocytic leukemia [

16]. Tyrian purple, mainly composed of 6,6′-dibromoindigo, is a dye extracted from sea snails and used as a biocompatible semiconductor material [

17]. Several bioactive indole oligomers have also been isolated from microorganisms. For example, a new indole dimer 2,2-di(1

H-indol-3-yl)ethyl butanoate with cytotoxic activity against the A549 lung carcinoma cell line was isolated from the marine-derived

Aeromonas sp. CB101 [

18]; an indole tetramer tetra(indol-3-yl)ethenone was isolated from a

Pseudovibrio denitrificans strain and showed effective cytotoxic activity against the L929 mouse fibroblasts cell line [

19]. Due to the good bioactivities of indole oligomers, several reports have focused on their biosynthesis. Cheng and co-workers identified a dye-decolorizing peroxidase LfDyP from the intestinal microbe

Lactobacillus fermentum, which oxidizes indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) to indole-3-aldehyde (IAld) and indole-3-carbinol (I3C), followed by spontaneous dimerization [

20]; Lee et al. and Du et al. completed the production of tyrian purple and indirubin in

E. coli using a

Methylophaga aminisulfidivorans-derived flavin-containing monooxygenase [

21]. Therefore, exploring indole oligomers and elucidating their biosynthesis is important for the bio-manufacturing of active indole derivatives.

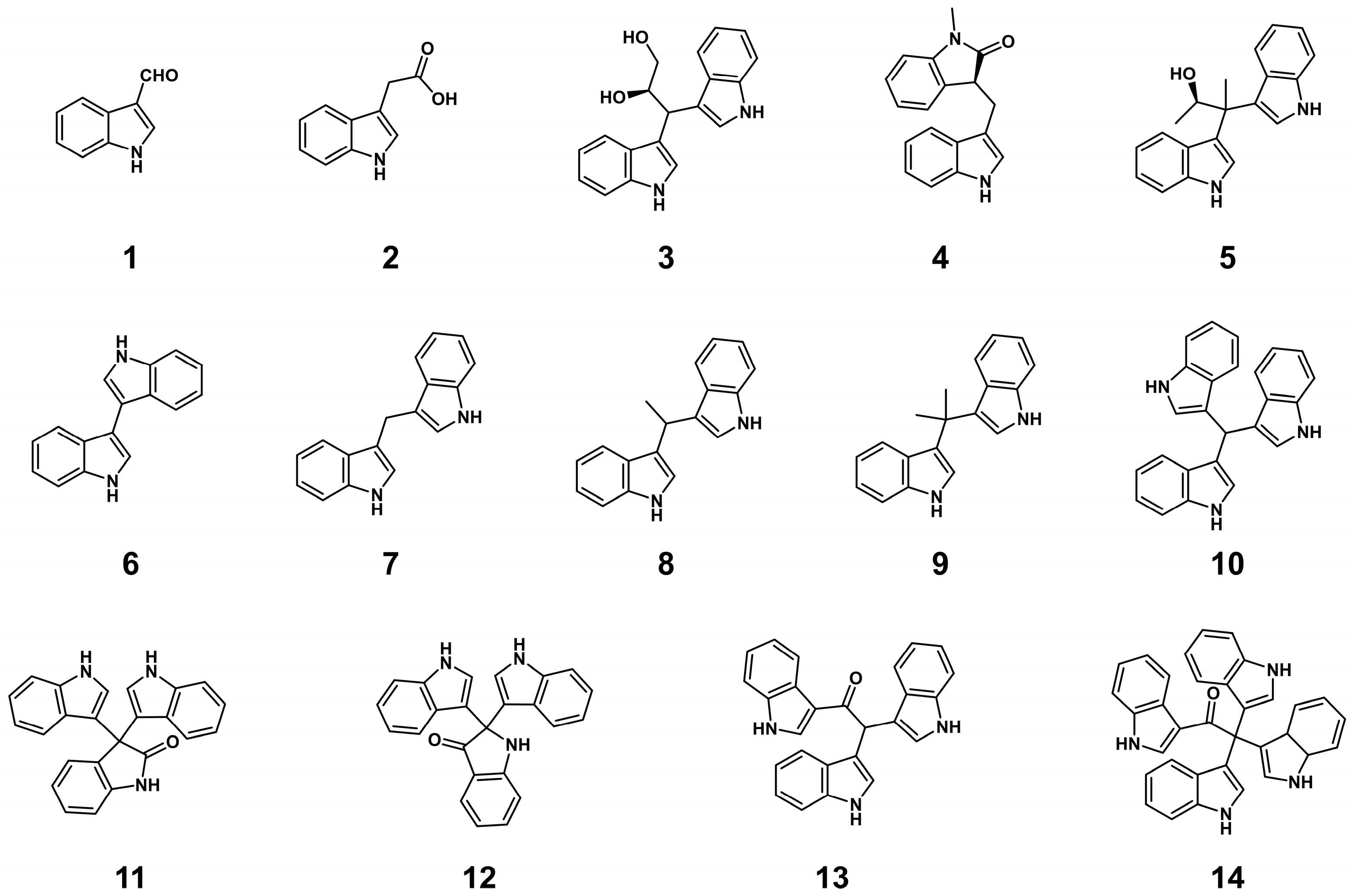

In this study, we investigated the secondary metabolites of deep-sea cold-seep-derived H. meridiana OUCLQ22-B7. Three known indole derivatives (1–3) were first isolated from the crude extract. Then precursor feeding experiments led to the activation of a series of indole oligomers, including two new (4 and 5) compounds and nine known indole alkaloids (6–14). Herein, we document the isolation, structure elucidation and bioactivity tests of these compounds.

2. Results and Discussions

The strain OUCLQ22-B7 was isolated from the deep-sea sediment collected at the South China Sea. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of OUCLQ22-B7 was cloned and compared against the EzTaxon-e server [

22]. The phylogenetic analysis of 16S rRNA of strain OUCLQ22-B7 was shown in

Figure S1. The result showed that it is highly similar to

Halomonas 16S rRNA with 99% identity to that of

Halomonas meridiana (GenBank accession number: ASM654012v1). Therefore, this strain was named as

H. meridiana OUCLQ22-B7. To mine its novel metabolites, we first employed the Landy medium, CYCG medium and Lactose medium to screen for the optimal fermentation medium of

H. meridiana OUCLQ22-B7 (

Figure S2). The CYCG medium has the highest abundance of natural products (

Figure S2). Subsequently, a large-scale fermentation (25 L) of

H. meridiana OUCLQ22-B7 was performed on CYCG medium at 37 °C for 2 days. Three compounds (

1–

3) were isolated from the crude extract (

Figure 1).

Compounds

1–

3 were isolated as a white amorphous powder, colorless oil and a purple-red amorphous powder, respectively. Comparing the

1H and

13C NMR data (

Figures S19–S24) of

1–

3 with those reported allowed them to be identified as known compounds indole-3-carboxaldehyde (

1) [

23], indole-3-acetic acid (

2) [

24], and fusarindole B (

3) [

25].

The structure of compound

3 indicated that the deep-sea cold-seep-derived

H. meridiana OUCLQ22-B7 has the ability to biosynthesize indole oligomers. Previous research showed that precursor feeding is an effective method to get more indole alkaloids in marine microorganisms, such as pseudboindoles A, pityriacitrin and scequinadoline A [

26,

27,

28]. To obtain more structurally diverse indole-derived natural products, we performed precursor feeding experiments (L-Trp and indole feeding) to stimulate the production of indole-based metabolites in

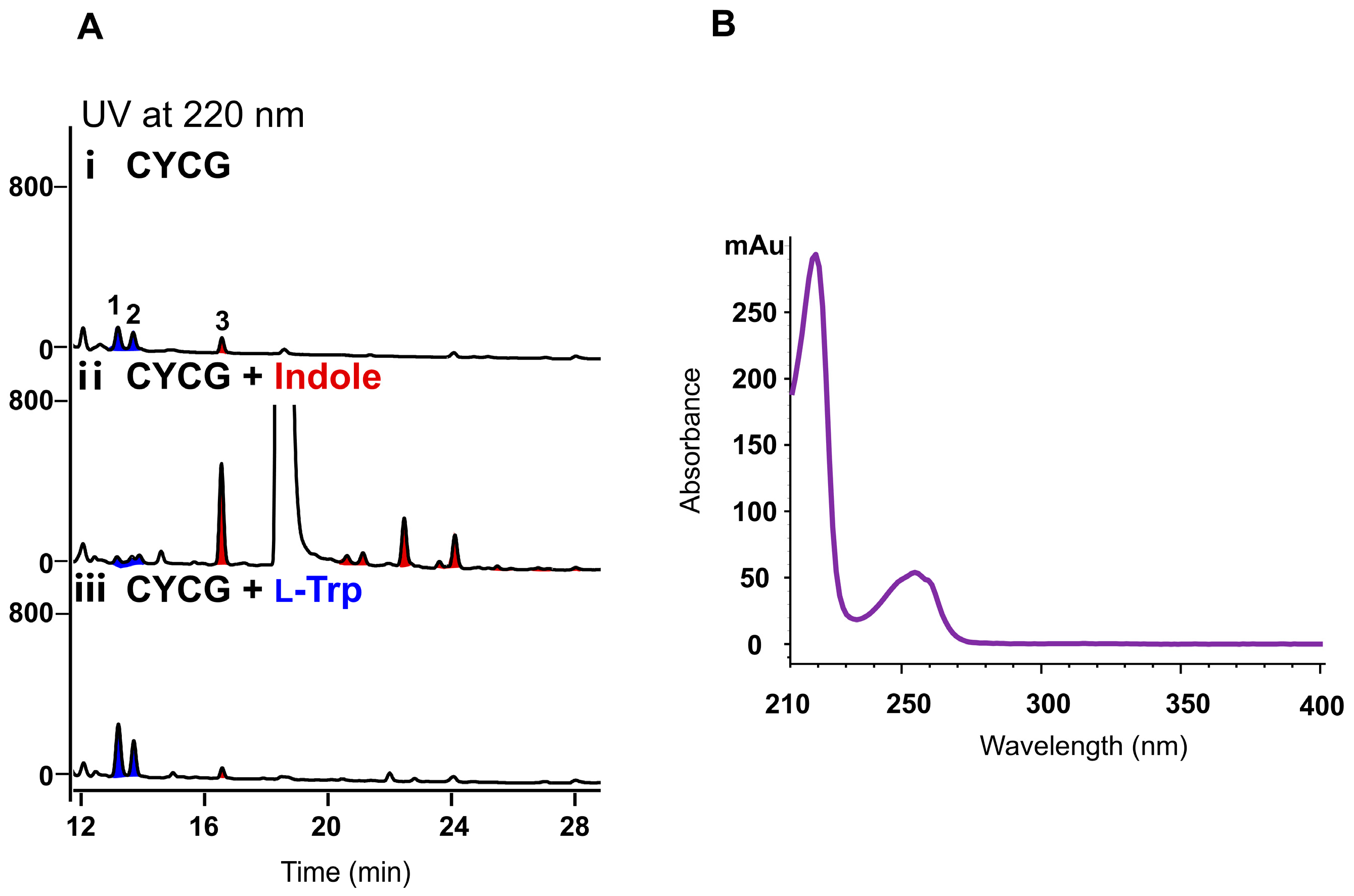

H. meridiana OUCLQ22-B7.

Noticeably, compared to the fermentation in CYCG medium, when supplemented with 2.5 mM L-Trp, the yield of compounds

1 and

2 increased as expected, and conversely, no obvious impact was observed for the production of compound

3, supporting the idea that L-Trp is the direct precursor for the biosynthesis of compounds

1 and

2 (

Figure 2A, panel iii). We then fed indole (2.5 mM) in the CYCG medium, and obvious effects on the metabolite profiles were detected. The production of compound

3 increased significantly (by 8.2-fold), and simultaneously a series of new peaks with similar UV spectra (

Figure 2B) to indole were accumulated (

Figure 2A, panel ii), indicating that indole might serve as the direct precursor for these compounds. To identify the chemical structures of these compounds, a total volume of 50 L fermentation of

H. meridiana OUCLQ22-B7 was conducted in CYCG medium supplemented with indole. This strategy led to the isolation of six indole dimers, four indole trimers and one indole tetramer; among them two indole dimers (compounds

4 and

5) are new compounds.

Compound

4 was isolated as a white amorphous powder. The HRESIMS spectrum showed a protonated molecule [M + H]

+ at

m/

z 277.1338 (

calcd for C

18H

17ON

2, 277.1296), indicating the molecular formula of C

18H

16ON

2, which required 12 degrees of unsaturation. The

1H NMR data in dimethyl sulfoxide-

d6 (DMSO-

d6) (

Table 1) showed nine olefinic protons [

δH 6.86 (1H, t,

J = 7.5 Hz); 7.04 (1H, m); 7.05 (1H, m); 7.07 (1H, m); 7.14 (1H, s); 7.22 (1H, br t); 7.23 (1H, br t); 7.35 (1H, d,

J = 8.0 Hz); 8.14 (1H, d,

J = 7.3 Hz)], one methine proton [

δH 5.87 (1H, d,

J = 10.6 Hz)], one methylene group [

δH 2.97 (1H, dd,

J = 1.3, 16.0 Hz); 3.76 (1H, dd,

J = 10.0, 16.5 Hz)], one methyl group [

δH 2.06 (3H, s)] and one exchangeable amino proton [

δH 11.08 (1H, s)]. Analysis of the

13C NMR data of compound

4 revealed eighteen carbon signals, including one carbonyl (

δC 169.0), fourteen aromatic carbons (

δC 111.9; 116.2; 116.8; 118.6; 118.8; 121.4; 122.5; 123.5; 124.2; 124.9; 127.2; 130.8; 136.9; 143.0), one methine (

δC 57.2), one methylene (

δC 37.3) and one methyl (

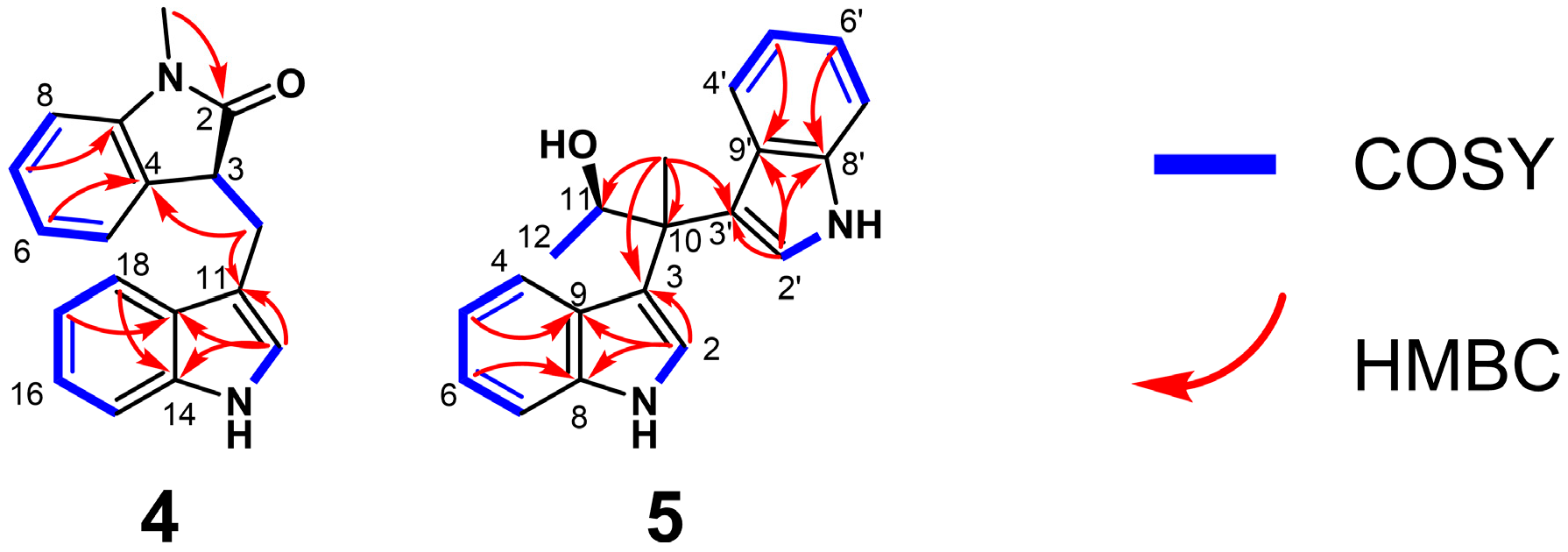

δC 23.6). Detailed analysis of the 2D NMR data established the connectivity of the fragments (

Figure 3). The H-15/H-16/H-17/H-18 and 13-NH/H3-12 fragments were confirmed by COSY correlations, while the key HMBC correlations from H-17 to C-19 and H-18 to C-14 established the substitution pattern. The structure of the 3-substituted indole moiety was determined by HMBC correlations from H3-12 to C-11, C-14 and C-19. The connection of C-10 to both C-3 and C-11 was established by COSY correlations between H2-10 and H-3, as well as HMBC correlations from H2-10 to C-11. Furthermore, the structure of the

ortho-disubstituted benzene ring was confirmed based on COSY correlations among the H-5/H-6/H-7/H-8 protons and HMBC correlations from H-6 to C-4 and H-7 to C-9. Subsequently, the presence of an acetamide linkage was deduced from the HMBC correction of the methyl protons (1-CH

3) to C-2. The N-1 atom was placed at C-9 based on NOESY correlations from 1-CH

3 to H-9 and H3-12. Finally, the HMBC correction from H2-10 to C-8, accounting for the degrees of unsaturation, allowed for the closure of the five-membered ring between C-9 and C-8, thereby confirming the planar structure of compound

4.

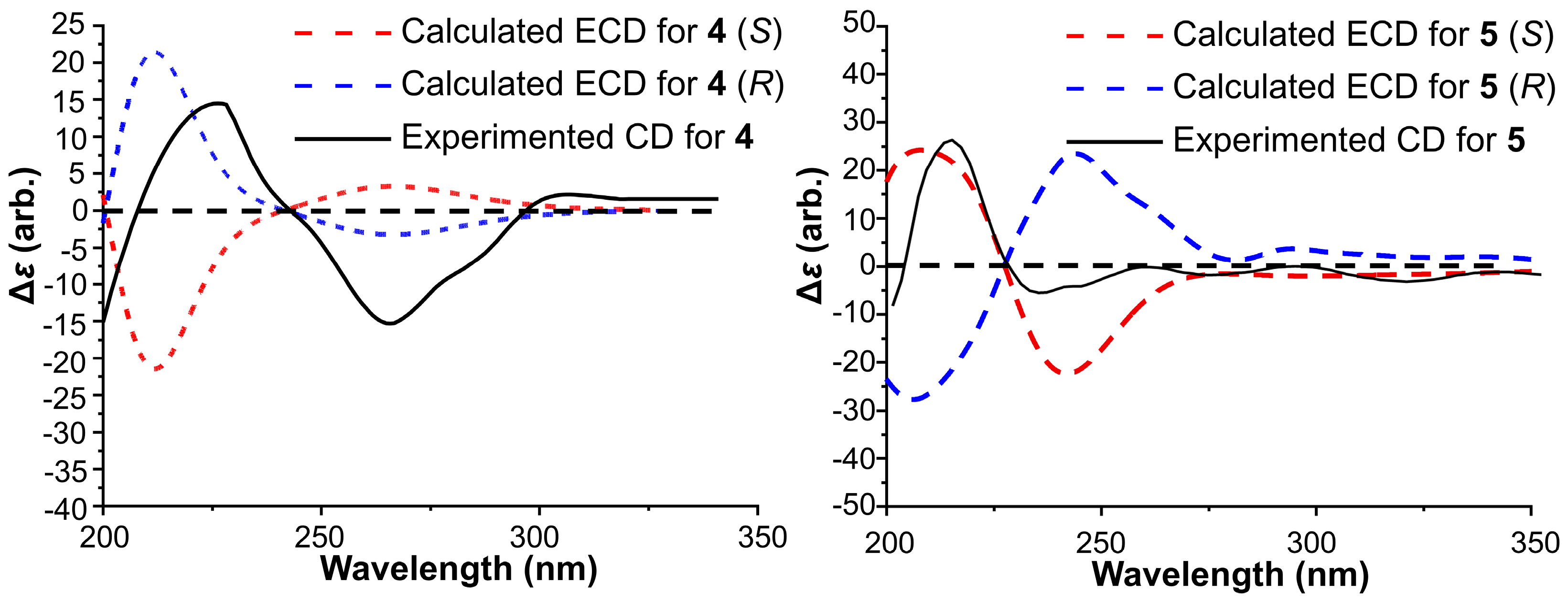

To determine the absolute configuration of compound

4, ECD calculations were performed (

Figure 4). The experimental CD spectrum of

4 matched well with the calculated ECD spectrum for

R-

4, assigning the configuration of C-9 as

R. Thus, compound

4 was identified as a new compound and named meribisindole A.

Compound

5 was obtained as a yellow amorphous powder. Its molecular formula was determined to be C

20H

20ON

2 based on the HRESIMS peak observed at

m/

z 305.1652 [M + H]

+ (

calcd for C

20H

21ON

2, 305.1609), corresponding to 12 degrees of unsaturation. The

1H NMR data exhibited ten aromatic protons [

δH 6.59 (2H, dd,

J = 7.7, 17.3 Hz); 6.85 (2H, dd,

J = 7.8, 15.7 Hz); 7.05 (2H, dd,

J = 8.0, 12.5 Hz); 7.25 (2H, dd,

J = 6.2, 7.6 Hz); 7.33 (2H, d,

J = 1.9 Hz)] suggestive of indole systems, one oxygenated methine [

δH 4.72 (1H, dd,

J = 6.1, 12.5 Hz)], two methyl groups [

δH 0.95 (3H, d,

J = 6.2 Hz); 1.74 (3H, s)] and two exchangeable amine protons [

δH 10.74 (1H, s); 10.79 (1H, s)]. The

13C NMR spectrum resolved 20 carbon resonances, classified into sixteen aromatic carbons (

δC 111.0; 111.2; 117.3; 117.5; 119.9; 120.1; 120.5; 120.7; 121.0; 121.2; 122.2; 122.5; 126.4; 126.9; 136.5; 136.8), one methine (

δC 71.3), one quaternary carbon (

δC 43.3) and two methyls (

δC 19.5; 21.1). Elucidation of the planar structure was achieved through interpretation of 2D NMR correlations (

Figure 3). The connectivity corresponding to the H-4–H-7 and H-1–H-2 fragments was defined by COSY correlations. Subsequently, the indole backbones were verified via HMBC correlations from H-5 to C-9, H-6 to C-8. Crucially, correlations from H-2 to C-3, C-8 and C-9 confirmed the presence of two 3-substituted indole moieties. The linkage between these fragments was established through the quaternary carbon C-10. HMBC correlations observed from the C-10 methyl protons (

δH 1.74) to C-3, C-3′, C-10 and C-11 demonstrated that both indole rings and the methyl group were attached to C-10. The remaining substructure was resolved by COSY correlations between H3-12 and H-11. Considering the molecular formula and the chemical shift of the methine carbon (

δC 71.3), a hydroxy group was assigned to C-11. These data collectively defined the planar constitution of

5.

The absolute configuration was addressed via ECD computational analysis (

Figure 4). The experimental CD spectrum of

5 showed excellent agreement with the calculated curve for the

S-

5, establishing the stereochemistry at C-11 as

S. Consequently, compound

5 was characterized as a new alkaloid and designated as meribisindole B.

Compounds

6–

14 were isolated as yellow amorphous powders. Through comparison of the

1H and

13C NMR data with data previously reported (

Figures S25–S42), they were identified as known compounds 3,3′-biindole (

6) [

29], 3,3′-diindolylmethane (

7) [

30], vibrindole A (

8) [

31], 3,3′-(1-methylethylidene)-bis-[1

H-indole] (

9) [

32], 3,3′,3′′-mthanetriyltris-1

H-indole (

10) [

33], 3,3-bis(1

H-indol-3-yl)-1

H-indol-2-one (

11) [

34], 2,2-bis(1

H-indol-3-yl)indolin-3-one (

12), metagenetriindole A (

13) [

35] and tetra(indol-3-yl)ethanone (

14) [

19].

Our precursor feeding experiments (

Figure 2) demonstrated that, in

H. meridiana OUCLQ22-B7, L-Trp is only the precursor of compounds

1 and

2, whereas indole probably serves as the precursor for the bisindole, trisindole and tetraindole alkaloids

3–

14. It is reported that indole is an intermediate in the biosynthesis of L-Trp through the shikimic acid pathway, transforming from indole 3-glycerol phosphate; or it can be reversibly converted from L-Trp by tryptophanase (TnaA) [

12]. Using the TnaA (Gene ID: 948221) from

E. coli as a probe, we did not find any homologous protein in

H. meridiana OUCLQ22-B7. Our results indicated that

H. meridiana OUCLQ22-B7 lacks the reverse pathway from L-Trp to indole. In addition, for the oligomization reactions of indole derivatives, previous reports showed that the

M. aminisulfidivorans-derived flavin-containing monooxygenase MaFMO can catalyze the hydroxylation of indole, and the hydroxylated products dimerize to indirubin by spontaneous oxidation [

36], while in the intestinal microbe

L. fermentum, a dye-decolorizing peroxidase LfDyP transforms IAA to IAId and I3C, followed by oxidation dimerization [

37]. The oligomization mechanism of compounds

3–

14 in

H. meridiana OUCLQ22-B7 remains unknown and needs further exploration.

The antibacterial activities of compounds

1–

14 were evaluated against three Gram-positive (

S. aureus CCARM 3090,

Enterococcus faecalis CCARM 5172 and

Enterococcus faecium CCARM 5203) and three Gram-negative (

Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883,

Escherichia coli CCARM 1009 and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa 15690) multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacterial strains. As shown in

Table 2, compounds

5 and

11 exhibited moderate antibacterial activities against

S. aureus CCARM3090 and

E. faecium CCARM 5203 (MICs = 25 μg/mL), respectively, while compound

11 exhibited ~10 times stronger anti-

S. aureus CCARM3090 activity (MIC = 0.098 μg/mL) than the positive control vancomycin (MIC = 0.78 μg/mL). This significant inhibitory activity of compound

11 against Gram-positive MDR strain

S. aureus CCARM 3090 highlights its potential as a lead compound for developing novel antibacterial agents, which may address the growing challenges of antimicrobial resistance.

Two fungal pathogens (C. albicans CMCC(F) 98001 and Fusarium oxysporum CICC 41029) were chosen to test the antifungal activities of compounds 1–14. Compounds 7–8 showed moderate antifungal activity against C. albicans CMCC(F) 98001 (MICs = 25 μg/mL); noticeably, compounds 4 and 7 exhibited ~60 times stronger anti-F. oxysporum CICC 41029 activities (MICs = 0.39 μg/mL) than the positive control amphotericin B (MIC = 25 μg/mL), and compound 8 exhibited 2 times stronger anti-F. oxysporum CICC 41029 activity (MIC = 12.5 μg/mL) than the positive control. Based on the MIC values of indole derivatives, we could conclude that, in general, indole dimers have more potent antifungal activities than indole monomers, indole trimers and the indole tetramer. Through comparison of the MICs of compounds 7–9, we found that single substitution of compound 7 at C10 with a methyl group (8) led to a weaker activity, and double substitution of compound 7 at C10 with methyl groups (9) led to loss of the activity (MIC > 50 µg/mL), indicating that C10 substituents can significantly influence the antifungal effects against the plant pathogen F. oxysporum CICC 41029 of indole dimers. These structure–activity relationships provide a valuable starting point for the development of more potent antifungal indole-dimer agents.

In addition, we evaluated the cytotoxic activities of compounds

1–

14 against two tumor cell lines, A549 (human non-small cell lung cancer cell line) and HepG2 (human liver cancer cell line). Only compound

14 displayed weak cytotoxicity effect against A549 cancer cell line, with IC

50 value of 14.12 μM (

Table S3). Remarkably, compound

11, which displayed effective anti-

S. aureus activity, and compounds

4,

7 and

8, which displayed potent anti-

F. oxysporum activity, are all non-toxic to cells at concentration of 15 μM, indicating their potential to be developed as anti-microbial drugs.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and General Procedures

H. meridiana OUCLQ22-B7 was cultured on modified LB medium (glucose 10 g/L, tryptone 10 g/L, yeast extract 5 g/L and sea-salt 33 g/L) for activation and DNA extraction. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed on an Agilent 1260 system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) using a YMC-Triart C18 column (150 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm, 12 nm). The gradient Acetonitrile (ACN) −0.1% formic acid in ddH2O program was as follows: 10% ACN (0–5 min), 10–100% ACN (5–40 min), 100% ACN (40–50 min) and 100–10% ACN (50–56 min). The semi-preparative HPLC separation was conducted on a Hitachi Primaide system (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a preparative YMC-Pack ODS-A C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm, 12 nm).

The 1D and 2D NMR spectra were recorded in DMSO-d6 on a Bruker Avance III 600 (600 MHz for 1H and 150 MHz for 13C, Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA). HRESIMS data were detected on a Thermo Electron LTQ-Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). CD spectra were acquired with a JASCO J-810 circular dichroism spectrometer (Jasco, Tokyo, Japan). All chemical reagents and solvents were purchased from standard commercial sources (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent, Shanghai, China).

3.2. Production and Isolation the Fermentation Products

H. meridiana OUCLQ22-B7 was activated on modified LB medium at 37 °C for 2 days. The stains were cultured in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 50 mL CYCG medium (casein acid hydrolysate 6 g/L, yeast extract 2 g/L, CaCl2·2H2O 1.4 g/L, glycerol 5 mL/L and sea-salt 30 g/L, pH 7.0), Landy medium (glucose 10 g/L, L-Glutamate sodium, 4 g/L, KCl 2 g/L, KH2PO4 1 g/L, MgSO4·7H2O 0.04 g/L, yeast extract 0.1 g/L, sea-salt 33 g/L, L-phenylalanine 2 mg/L, MnSO4 5 mg/L and CuSO4 0.16 mg/L, pH 7.2 ) or Lactose medium (lactose 32 g/L, peptone 8.8 g/L, yeast extract 7.5 g/L and sea-salt 33 g/L, pH 8.5), respectively, to screen for the optimal fermentation medium. Large-scale fermentation was carried out in a total volume of 25 L of CYCG medium at 37 °C for 2 days with shaking (180 rpm). For the precursor feeding experiments, CYCG medium was supplemented with sterilized 2.5 mM indole or L-Trp.

After incubation, the fermentation products were extracted twice with a double volume of EtOAc and then concentrated using rotary evaporator. The EtOAc extract of fermentation products was partitioned between 90% MeOH and n-hexane (1:1, v/v) to yield two residues. The aqueous MeOH layer was subjected to reversed-phase column chromatography with 10–100% MeOH to afford nine fractions (Fr.1–Fr.9). Fraction 4 (Fr.4), eluted with MeOH: H2O (25:75, v/v), was further purified via semi-preparative HPLC (ACN: H2O, 30:70, v/v, 2 mL/min) to yield compounds 1–3.

For the indole precursor feeding experiments, the fermentation products were treated as described below. The aqueous MeOH layer was subjected to reversed-phase column chromatography with 40–100% MeOH to afford six fractions (Fr.1-Fr.6). Compounds 4–9 were obtained from Fraction 2 (eluted with MeOH-H2O 50:50, v/v) by semi-preparative HPLC (ACN: H2O, 45:55, v/v, 2 mL/min). Compounds 10–14 were obtained from Fraction 5 (eluted with MeOH-H2O 80:20, v/v) by semi-preparative HPLC (ACN: H2O, 70:30, v/v, 2 mL/min).

meribisindole A (

4): yellow powder; UV (ACN) λ

max 220, 280 nm;

1H and

13C NMR data,

Table 1; HRESIMS

m/

z 277.13 [M + H]

+,

Figure S5, (calcd for C

18H

16ON

2 277.12)

meribisindole B (

5): yellow powder; UV (ACN) λ

max 220, 280 nm;

1H and

13C NMR data,

Table 1; HRESIMS

m/

z 305.16 [M + H]

+,

Figure S13, (calcd for C

20H

20ON

2 305.16)

3.3. Electronic Circular Dichroism (ECD) Calculations

Monte Carlo conformational searches were performed using Spartan’10 (Hongcam Software Technologies, Beijing, China) with the Merck Molecular Force Field (MMFF). Conformers with a Boltzmann population greater than 0.6% were selected for ECD calculations. Geometry optimization was subsequently conducted at the B3LYP/6-31G (d,p) level in MeOH using the CPCM polarizable conductor calculation model. Theoretical ECD spectra for compounds 4 and 5 were calculated in MeOH using time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) at the B3LYP/6-31+G (d,p) level. Rotatory strengths for the first 30 excited states were calculated. Finally, ECD spectra were generated using SpecDis 1.6 (University of Würzburg, Bavaria, Germany) and GraphPad Prism 9 (University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA) by applying Gaussian band shapes with sigma = 0.3 eV.

3.4. In Vitro Antifungal Assay and Antibacterial Assay

To test the (Minimum Inhibitory Concentration) MIC values of compounds 1–14 against plant pathogen fungal strains C. albicans CMCC(F) 98001 and F. oxysporum CICC 41029. First, the tested strains were grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium (potato 200 g/L, glucose 20 g/L and agar 20 g/L) at 30 °C for 5 days. Fresh cultures of these strains were inoculated into potato dextrose broth (PDB) medium (potato 200 g/L and glucose 20 g/L) and cultured at 30 °C for 12 h to generate a stock culture.

To measure the MIC values of compounds 1–14 against bacterial strains S. aureus CCARM 3090, E. coli CCARM 1009, E. faecalis CCARM 5172, E. faecium CCARM 5203, K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883 and P. aeruginosa 15690. The tested strains were grown in LB medium at 37 °C for 12 h, then adjusted to 106 CFU/mL with LB medium to generate a stock culture.

Then, the cultures were adjusted and seeded into 96-well plates at 106 CFU/mL per well (180 μL). The tested compounds 1–14 were dissolved in MeOH to obtain a stock solution (50 mg/mL). The sample stock solutions were diluted with MeOH to yield a series of concentrations (0.098, 0.19, 0.39, 0.78, 1.56, 3.12, 6.25, 12.5 and 25 μg/mL). Finally, 20 μL of the sample solution was added into each 96-well plate follower by incubation at 30 °C for 18 h. After incubation, the antifungal activity or antibacterial activity of compounds 1–14 was measured via a BioTek Epoch 2 microplate reader (620 nm, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The MIC value was defined as the lowest tested compound concentration at which no bacterial or fungal growth was observed, corresponding to the first clear well in the serial dilution.

Amphotericin B (AMB) was used as a positive control for antifungal activity; Vancomycin (Van) was used as a positive control for antibacterial activity; PDB/LB medium was used as a blank control and MeOH was used as a negative control, respectively.

3.5. Cell Culture and Cytotoxic Assays

Human non-small cell lung cancer cell line A549 and human hepatocarcinoma cell line HepG2 (Wang Xin Lab, Hainan University, Haikou, China) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (v/v). Cell lines were grown at 37 °C in an atmosphere with 5% CO2. Adherent cells (5 × 103 per well) and suspension cells (8 × 103 cells per well) were seeded into each 96-well plate follower by incubation at 37 °C for 24 h. Subsequently, 100 μL of the sample solution was added into each 96-well plate and then cultured at 37 °C for 72 h. After incubation, 20 μL MTT (5 mg/mL) was added into each 96-well plate and then cultured at 37 °C for 4 h, followed by treatment with 200 μL DMSO for additional 10 min with shaking. Finally, the microplate reader (560 nm) was employed to measure fluorescence intensity. The samples were tested at a concentration of 15 μM to evaluate cytotoxic activity, and if significant inhibitory effect was observed, their IC50 values were subsequently determined.

DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS was used as a blank control. Samples were dissolved in MeOH, which was used as a negative control.