Precision-Engineered Dermatan Sulfate-Mimetic Glycopolymers for Multi-Targeted SARS-CoV-2 Inhibition †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Rational Screening, Design, and Synthesis of DS-Mimetic Disaccharide Modules

2.2. Preparation, Characterization, and Protein-Binding Assessment of Diverse DS-Mimetic Glycopolymers

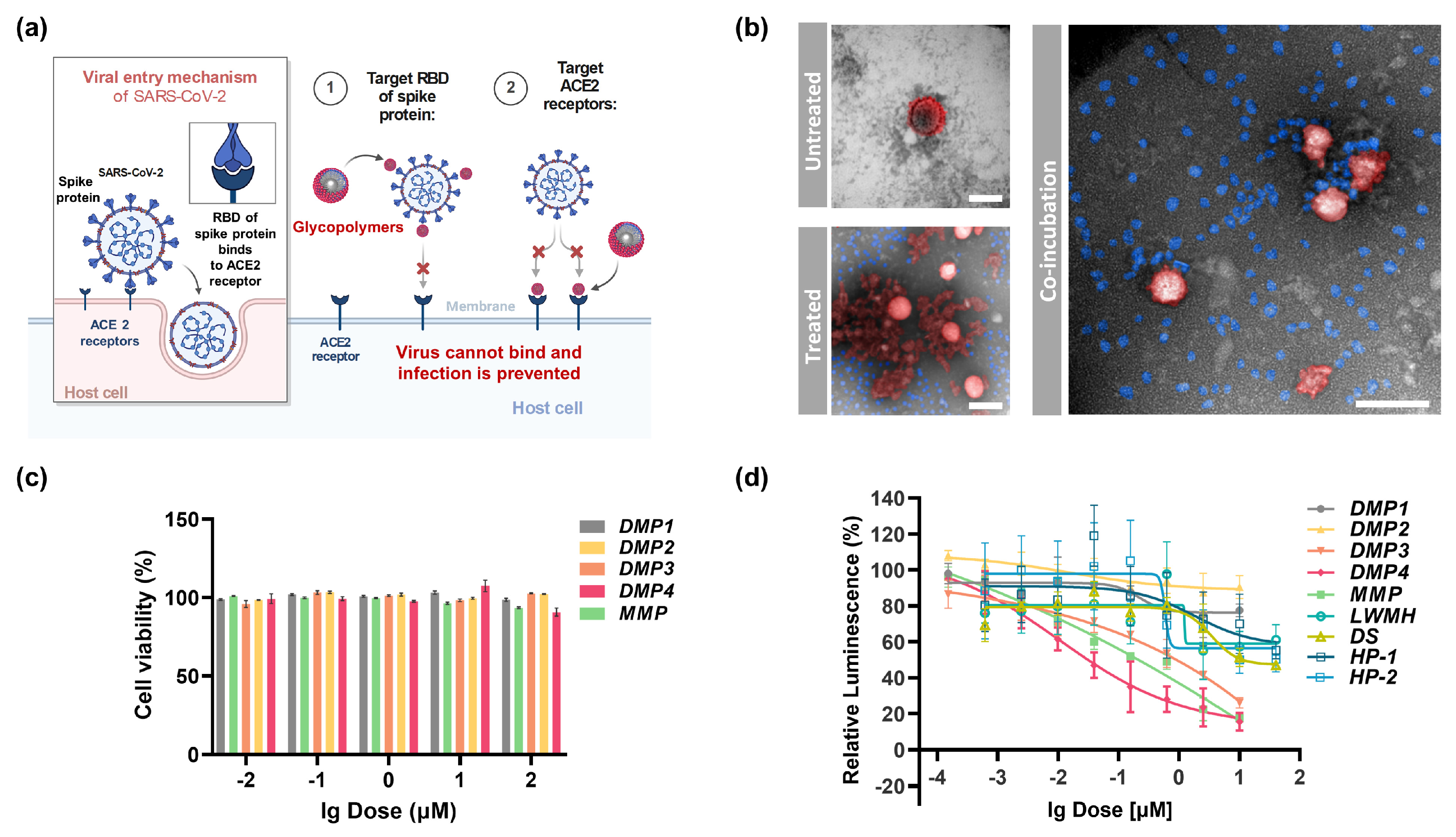

2.3. In Vitro Antiviral Activity and Cellular Uptake of DS-Mimetic Glycopolymers

3. Discussion

3.1. Strengths and Key Findings of the Study

3.2. Study Limitations and Outlooks

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Synthesis of the Engineered Dermatan Sulfate–Mimetic Glycopolymers

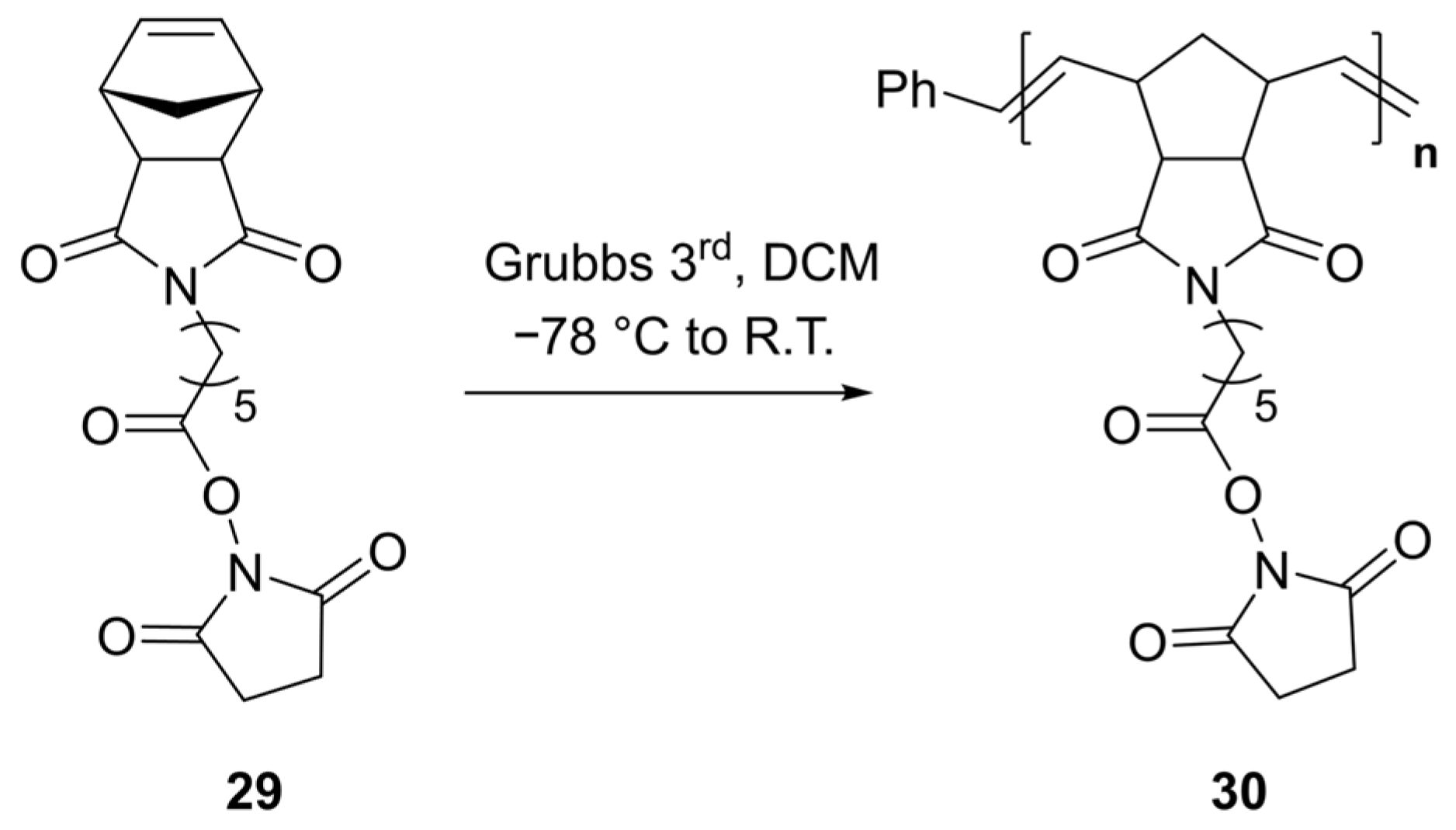

4.2.1. General Procedure for the Preparation of Polymer Containing NHS Ester (30, DP = 50)

4.2.2. General Procedure for Post-Modification of NHS-Containing Polymer with Sugar Units

4.2.3. General Procedure for Fluorescent Labeling of Glycopolymers by Post-Modification

4.3. SPR Analysis

4.3.1. Immobilization of Protein on a CM5 Sensor Chip

4.3.2. Kinetic Binding Affinity Assays

4.4. Cell Viability Assay

4.5. SARS-CoV-2 Pseudovirus Neutralization Assay

4.5.1. SARS-CoV-2 Pseudovirus Production and Transient Transfection of ACE2

4.5.2. SARS-CoV-2 Pseudovirus Neutralization Assays

4.6. Confocal Microscopy for the Localization of Cellular Uptake of Glycopolymers

4.6.1. Confocal Microscopy for Internalization of Vero Cell

4.6.2. Confocal Microscopy for Internalization of Vero Cells at Different Time Points

4.7. Flow Cytometric Analysis of Cellular Uptake of the Glycopolymers

4.8. TR-FRET Heparanase Inhibition Assay

4.9. In Vitro Activity Assays of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Inhibitors

4.9.1. SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Protein Expression In Vitro

4.9.2. SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Inhibition Assay

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Related Coronavirus 2 |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| SARS-CoV | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Related Coronavirus |

| ACE2 | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 |

| GAG | Glycosaminoglycan |

| HS | Heparan Sulfate |

| DS | Dermatan Sulfate |

| HP | Heparin |

| RBD | Receptor Binding Domain |

| HPSE | Heparanase |

| HSPGs | Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans |

| Mpro | Main Protease |

| Bn | Benzy |

| Cbz | Carbobenzyloxy |

| IdoA | Aldonic Acid |

| GalNAc | N-Acetylgalactosamine |

| TR-FRET | Time-Resolved Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer |

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/more-resources (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Montcho, Y.; Amoussouvi, K.T.; Atchadé, M.N.; Salako, K.V.; Hounkonnou, M.N.; Wolkewitz, M.; Kakaï, R.G. Assessing the potential seasonality of COVID-19 dynamic in Africa: A mathematical modeling study. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 11, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzalone, A.J.; Vest, M.T.; Schissel, M.E.; Price, B.; Hillegass, W.B.; Horswell, R.; Chu, S.; Rosen, C.J.; Miele, L.; Santangelo, S.L.; et al. Higher mortality following SARS-CoV-2 infection in rural versus urban dwellers persists for two years post-infection. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Huraimel, K.; Alhosani, M.; Kunhabdulla, S.; Stietiya, M.H. SARS-CoV-2 in the environment: Modes of transmission, early detection and potential role of pollutions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 744, 140946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callaway, E. Could new COVID variants undermine vaccines? Labs scramble to find out. Nature 2021, 589, 177–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavine, J.S.; Bjornstad, O.N.; Antia, R. Immunological characteristics govern the transition of COVID-19 to endemicity. Science 2021, 371, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarrondo, F.J.; Fulcher, J.A.; Goodman-Meza, D.; Elliott, J.; Hofmann, C.; Hausner, M.A.; Ferbas, K.G.; Tobin, N.H.; Aldrovandi, G.M.; Yang, O.O. Rapid decay of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in persons with mild COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1085–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, D.; Han, J. COVID-19 vaccines and beyond. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2024, 21, 207–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, T.; Su, X.; Sun, J.; Liu, S.; Huang, M.; Li, W.; Luo, C.; Cheng, L.; Wei, R.; Song, T.; et al. Dynamic immune landscape in vaccinated-BA.5-XBB.1.9.1 reinfections revealed a 5-month protection-duration against XBB infection and a shift in immune imprinting. Ebiomedicine 2024, 99, 104903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.; Yang, N.; Deng, J.; Liu, K.; Yang, P.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, C. Inhibition of SARS pseudovirus cell entry by lactoferrin binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Ge, J.; Yu, J.; Shan, S.; Zhou, H.; Fan, S.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; et al. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature 2020, 581, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.-H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, P.; Ren, W.; Yu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Yuan, B.; Song, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 main protease cleaves MAGED2 to antagonize host antiviral defense. mBio 2023, 14, e01373-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VK, P.; Rath, S.P.; Abraham, P. Computational designing of a peptide that potentially blocks the entry of SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251913. [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki, K.; Adachi, N.; Tun, M.M.N.; Ikeda, A.; Moriya, T.; Kawasaki, M.; Yamasaki, T.; Kubota, T.; Nagashima, I.; Shimizu, H.; et al. Core fucose-specific pholiota squarrosa lectin (PhoSL) as a potent broad-spectrum inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 infection. FEBS J. 2023, 290, 412–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-J.; Le, U.N.P.; Liu, J.-J.; Li, S.-R.; Chao, S.-T.; Lai, H.-C.; Lin, Y.-F.; Hsu, K.-C.; Lu, C.-H.; Lin, C.-W. Combining virtual screening with cis-/trans-cleavage enzymatic assays effectively reveals broad-spectrum inhibitors that target the main proteases of SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV. Antivir. Res. 2023, 216, 105653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varki, A.; Cummings, R.D.; Esko, J.D.; Stanley, P.; Hart, G.W.; Aebi, M.; Mohnen, D.; Kinoshita, T.; Packer, N.H.; Prestegard, J.H.; et al. (Eds.) Essentials of Glycobiology; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Clausen, T.M.; Sandoval, D.R.; Spliid, C.B.; Pihl, J.; Perrett, H.R.; Painter, C.D.; Narayanan, A.; Majowicz, S.A.; Kwong, E.M.; McVicar, R.N.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection depends on cellular heparan sulfate and ACE2. Cell 2020, 183, 1043–1057.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Jin, W.; Sood, A.; Montgomery, D.W.; Grant, O.C.; Fuster, M.M.; Fu, L.; Dordick, J.S.; Woods, R.J.; Zhang, F.; et al. Characterization of heparin and severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike glycoprotein binding interactions. Antivir. Res. 2020, 181, 104873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, P.S.; Oh, H.; Kwon, S.-J.; Jin, W.; Zhang, F.; Fraser, K.; Hong, J.J.; Linhardt, R.J.; Dordick, J.S. Sulfated polysaccharides effectively inhibit SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Cell Discov. 2020, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chopra, P.; Li, X.; Bouwman, K.M.; Tompkins, S.M.; Wolfert, M.A.; de Vries, R.P.; Boons, G.-J. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans as attachment factor for SARS-CoV-2. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, R.; Farrag, M.; Sharma, P.; Shi, D.; Shami, A.A.; Misra, S.K.; Ray, P.; Shukla, J.; Zhang, F.; Linhardt, R.J.; et al. The sea cucumber thyonella gemmata contains a low anticoagulant sulfated fucan with high anti-SARS-CoV-2 actions against wild-type and delta variants. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 1463–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomin, V.H.; Zhang, F.; Dordick, J.S. Role, binding properties, and potential therapeutical use of glycosaminoglycans and mimetics in SARS-CoV-2 infection. In memory of dr. Robert linhardt (1953–2025). Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 362, 123703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tree, J.A.; Turnbull, J.E.; Buttigieg, K.R.; Elmore, M.J.; Coombes, N.; Hogwood, J.; Mycroft-West, C.J.; Lima, M.A.; Skidmore, M.A.; Karlsson, R.; et al. Unfractionated heparin inhibits live wild type SARS-CoV-2 cell infectivity at therapeutically relevant concentrations. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 178, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, R.; Sharp, J.S.; Zhang, F.; Pomin, V.H.; Ashpole, N.M.; Mitra, D.; McCandless, M.G.; Jin, W.; Liu, H.; Sharma, P.; et al. Effective inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 entry by heparin and enoxaparin derivatives. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e01987-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mycroft-West, C.J.; Su, D.; Pagani, I.; Rudd, T.R.; Elli, S.; Gandhi, N.S.; Guimond, S.E.; Miller, G.J.; Meneghetti, M.C.Z.; Nader, H.B.; et al. Heparin inhibits cellular invasion by SARS-CoV-2: Structural dependence of the interaction of the spike S1 receptor-binding domain with heparin. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 120, 1700–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustyuzhanina, N.E.; Bilan, M.I.; Dmitrenok, A.S.; Tsvetkova, E.A.; Nifantiev, N.E.; Usov, A.I. Oversulfated dermatan sulfate and heparinoid in the starfish lysastrosoma anthosticta: Structures and anticoagulant activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 261, 117867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habuchi, O. Functions of chondroitin/dermatan sulfate containing GalNAc4,6-disulfate. Glycobiology 2022, 32, 664–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Xu, Y.; Du, M.; Fan, Y.; Zou, R.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; Wang, W.; Li, F. A novel 4-O-endosulfatase with high potential for the structure-function studies of chondroitin sulfate/dermatan sulfate. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 305, 120508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inubushi, T.; Nag, P.; Sasaki, J.-I.; Shiraishi, Y.; Yamashiro, T. The significant role of glycosaminoglycans in tooth development. Glycobiology 2024, 34, cwae024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Williams, A.; Zhang, X.; Fu, L.; Xia, K.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, J.; Koffas, M.; Linhardt, R.J. Specificity and action pattern of heparanase bp, a β-glucuronidase from burkholderia pseudomallei. Glycobiology 2019, 29, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangarajan, S.; Richter, J.R.; Richter, R.P.; Bandari, S.K.; Tripathi, K.; Vlodavsky, I.; Sanderson, R.D. Heparanase-enhanced shedding of syndecan-1 and its role in driving disease pathogenesis and progression. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2020, 68, 823–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agelidis, A.; Shukla, D. Heparanase: From Basic Research to Clinical Applications; Vlodavsky, I., Sanderson, R.D., Ilan, N., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 759–770. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, J.; Lu, M.; Shi, M.; Cheng, X.; Kwakwa, K.A.; Davis, J.L.; Su, X.; Bakewell, S.J.; Zhang, Y.; Fontana, F.; et al. Heparanase blockade as a novel dual-targeting therapy for COVID-19. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e00057-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, A.; Koike, T.; Kuboki, Y.; Komaba, S.; Kosono, S.; Aswathy, M.; Anzai, I.; Watanabe, T.; Toshima, K.; Takahashi, D. Synthesis of low-molecular-weight fucoidan analogue and its inhibitory activities against heparanase and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202411760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greinacher, A.; Farner, B.; Kroll, H.; Kohlmann, T.; Warkentin, T.E.; Eichler, P. Clinical features of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia including risk factors for thrombosis. Thromb. Haemost. 2017, 94, 132–135. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, C.; Pouyan, P.; Lauster, D.; Trimpert, J.; Kerkhoff, Y.; Szekeres, G.P.; Wallert, M.; Block, S.; Sahoo, A.K.; Dernedde, J.; et al. Polysulfates block SARS-CoV-2 uptake through electrostatic interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 15870–15878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulsalam, H.; Li, J.; Loka, R.S.; Sletten, E.T.; Nguyen, H.M. Heparan sulfate-mimicking glycopolymers bind SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in a length- and sulfation pattern-dependent manner. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 1411–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Gao, L.; Shao, M.; Cai, C.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Fan, F.; Han, Y.; Liu, M.; et al. End-functionalised glycopolymers as glycosaminoglycan mimetics inhibit HeLa cell proliferation. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 4714–4722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, O.C.; Wentworth, D.; Holmes, S.G.; Kandel, R.; Sehnal, D.; Wang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Sheppard, P.; Grelsson, T.; Coulter, A.; et al. Generating 3D models of carbohydrates with GLYCAM-web. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nivedha, A.K.; Thieker, D.F.; Hu, H.; Woods, R.J. Vina-carb: Improving glycosidic angles during carbohydrate docking. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 892–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemker, H.C. A century of heparin: Past, present and future. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2016, 14, 2329–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogwood, J.; Mulloy, B.; Lever, R.; Gray, E.; Page, C.P. Pharmacology of heparin and related drugs: An update. Pharmacol. Rev. 2023, 75, 328–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, S.A.; Rojas-Valencia, N.; Gómez, S.; Lans, I.; Restrepo, A. Initial recognition and attachment of the zika virus to host cells: A molecular dynamics and quantum interaction approach. Chembiochem 2022, 23, e202200351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowbridge, J.M.; Gallo, R.L. Dermatan sulfate: New functions from an old glycosaminoglycan. Glycobiology 2002, 12, 117R–125R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohman, G.J.S.; Hunt, D.K.; Högermeier, J.A.; Seeberger, P.H. Synthesis of Iduronic Acid Building Blocks for the Modular Assembly of Glycosaminoglycans. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 7559–7561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeap, S.P.; Lim, J.; Ngang, H.P.; Ooi, B.S.; Ahmad, A.L. Role of particle–particle interaction towards effective interpretation of Z-average and particle size distributions from dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2018, 18, 6957–6964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, Y.; Yasuda, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Koike, M.; Nishida, Y.; Kobayashi, K. Inhibition of alzheimer amyloid aggregation with sulfated glycopolymers. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 2129–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koide, H.; Yoshimatsu, K.; Hoshino, Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Okajima, A.; Ariizumi, S.; Narita, Y.; Yonamine, Y.; Weisman, A.C.; Nishimura, Y.; et al. A polymer nanoparticle with engineered affinity for a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF165). Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshiko, M.; Yu, H.; Hirokazu, S. Glycopolymer Nanobiotechnology. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 1673–1692. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, C.; Despras, G.; Lindhorst, T.K. Organizing multivalency in carbohydrate recognition. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 3275–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Pang, H.; Li, S.J. Heparin interacts with the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 and inhibits its activity. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2022, 267, 120595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Li, X.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhou, L.; Lin, Y.; Wu, D.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H.; et al. Identify potent SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors via accelerated free energy perturbation-based virtual screening of existing drugs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 27381–27387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F. Recent studies on reaction pathways and applications of sugar orthoesters in synthesis of oligosaccharides. Carbohydr. Res. 2007, 342, 345–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, R.; Overkleeft, H.S.; van der Marel, G.A.; Codée, J.D.C. 2,2-dimethyl-4-(4-methoxy-phenoxy) butanoate and 2,2-dimethyl-4-azido butanoate: Two new pivaloate-ester-like protecting groups. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 2270–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Glycopolymer | Sugar units | Mw (NMR) a | Rh (nm) b | Rm (nm) c | Zeta-potential b | DSS d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMP1 | DM1 (0S) | 33 kDa | 348.20 | 27.98 | −18.4 | 82% |

| DMP2 | DM2 (G4/6S) | 36 kDa | 327.30 | 21.09 | −21.8 | 88% |

| DMP3 | DM3 (I2/4S) | 31 kDa | 246.60 | 12.52 | −24.2 | 83% |

| DMP4 | DM4 (I2/4S, G4/6S) | 33 kDa | 269.45 | 15.83 | −23.3 | 86% |

| MMPe | GalNAc (3/4/6S) | 34 kDa | 231.35 | 21.99 | −12.0 | 84% |

| Compound and Protein | ka (M−1s−1) a | kd (1/s) a | KD (M) a |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMP1-Spike | 2.25 × 104 | 1.10 × 10−3 | 4.89 × 10−7 |

| DMP2-Spike | 1.09 × 104 | 3.90 × 10−3 | 3.58 × 10−7 |

| DMP3-Spike | 1.61 × 104 | 4.72 × 10−3 | 2.92 × 10−7 |

| DMP4-Spike | 2.27 × 104 | 4.00 × 10−3 | 1.77 × 10−7 |

| MMP-Spike | 1.78 × 104 | 4.75 × 10−3 | 2.67 × 10−7 |

| DMP4-ACE2 | 4.41 × 103 | 4.80 × 10−3 | 1.08 × 10−6 |

| Entry | Compounds | (nM) | (μg/mL) | (μM) | (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DMP1 | 5.48 | 0.18 | 2.01 | 66.33 |

| 2 | DMP2 | 21.35 | 0.77 | 1.31 | 47.16 |

| 3 | DMP3 | 8.12 | 0.25 | 0.47 | 14.57 |

| 4 | DMP4 | 3.67 | 0.12 | 0.89 | 29.37 |

| 5 | MMP | 5.39 | 0.18 | 0.71 | 24.14 |

| 6 | DS | 1249 | 43.72 | - | - |

| 7 | LMWH c | 18.13 | 0.082 | >1000 | >4500 |

| 8 | Heparin | 3.74 | 0.056 | 8.97 | 134.55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Gao, L.; Yang, C.; Yin, M.; Sun, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, C.; Hinkley, S.F.R.; Yu, G.; Cai, C. Precision-Engineered Dermatan Sulfate-Mimetic Glycopolymers for Multi-Targeted SARS-CoV-2 Inhibition. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120486

Wang L, Gao L, Yang C, Yin M, Sun J, Yang L, Liu C, Hinkley SFR, Yu G, Cai C. Precision-Engineered Dermatan Sulfate-Mimetic Glycopolymers for Multi-Targeted SARS-CoV-2 Inhibition. Marine Drugs. 2025; 23(12):486. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120486

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Lihao, Lei Gao, Chendong Yang, Mengfei Yin, Jiqin Sun, Luyao Yang, Chanjuan Liu, Simon F. R. Hinkley, Guangli Yu, and Chao Cai. 2025. "Precision-Engineered Dermatan Sulfate-Mimetic Glycopolymers for Multi-Targeted SARS-CoV-2 Inhibition" Marine Drugs 23, no. 12: 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120486

APA StyleWang, L., Gao, L., Yang, C., Yin, M., Sun, J., Yang, L., Liu, C., Hinkley, S. F. R., Yu, G., & Cai, C. (2025). Precision-Engineered Dermatan Sulfate-Mimetic Glycopolymers for Multi-Targeted SARS-CoV-2 Inhibition. Marine Drugs, 23(12), 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120486