Lipidomic Screening of Marine Diatoms Reveals Release of Dissolved Oxylipins Associated with Silicon Limitation and Growth Phase

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Identification of Fatty Acids and Oxylipins

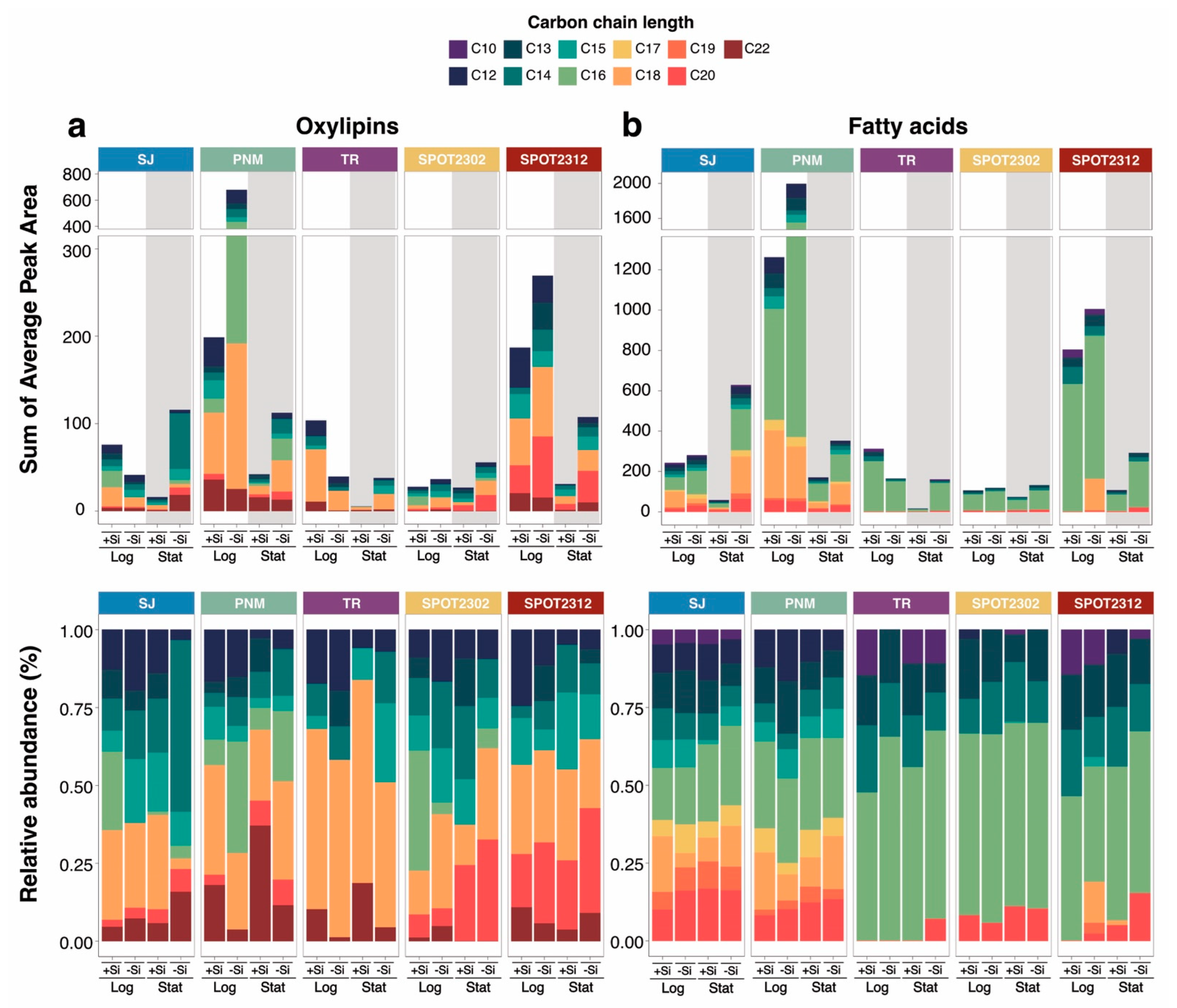

2.2. Increased Release of Dissolved Oxylipins and Fatty Acids with Si-Limitation

2.3. Differential Release of Oxylipins with Growth Phase

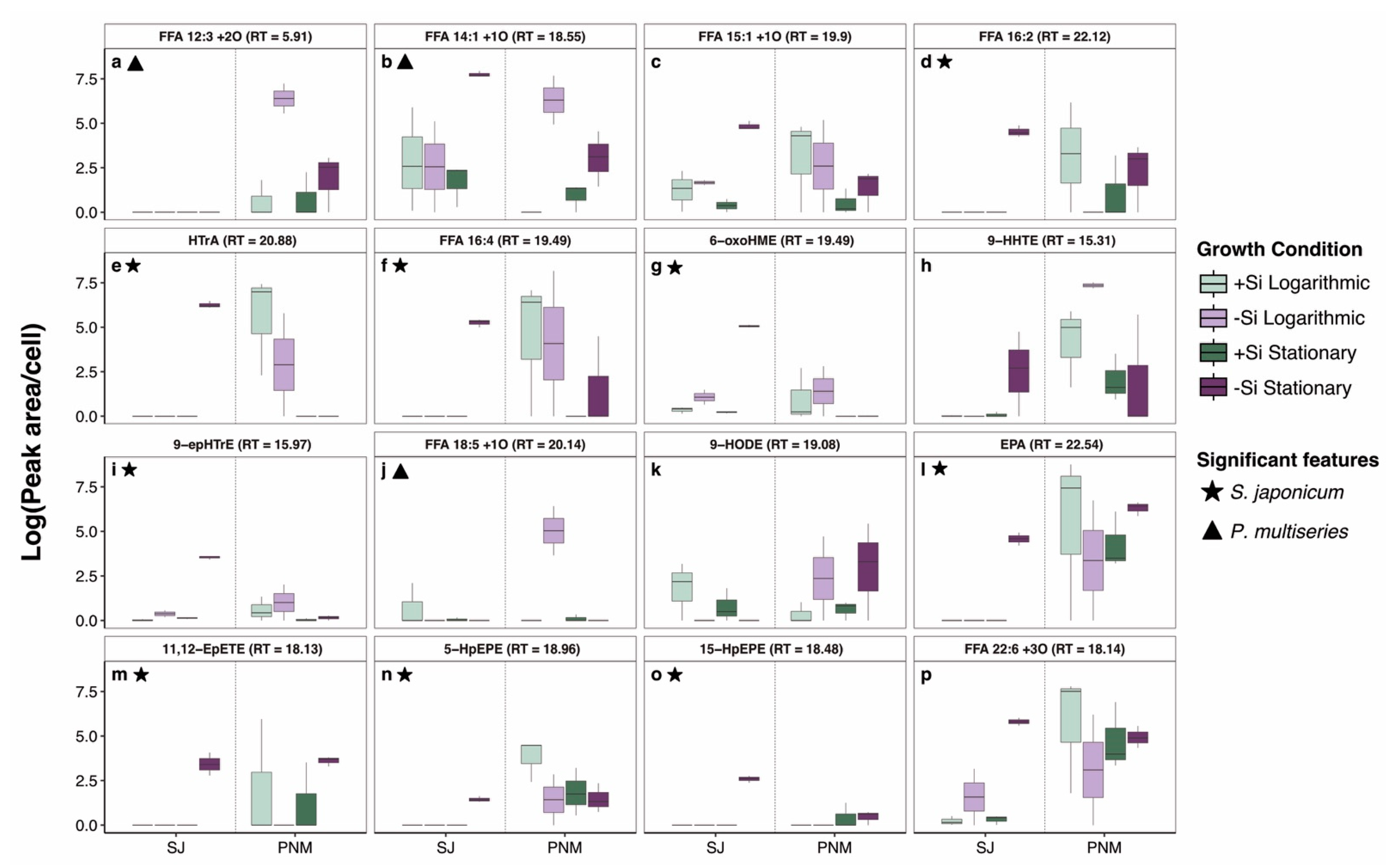

2.4. Drivers of Species-Specific, Dissolved Lipidomes

2.5. Oxylipin Concentrations and Ecological Implications

3. Conclusions and Broader Impacts

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Diatom Cultures

4.2. Lipid Extraction and Data Acquisition

4.3. Lipidomic Analysis

4.4. Statistical Analysis

4.5. Lipoxygenase Sequence Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Si-limitation | Silicon limitation |

| POM | Particulate organic matter |

| DOM | Dissolved organic matter |

| TEP | Transparent exopolymer particles |

| PUA | Polyunsaturated aldehyde |

| LOFA | Linear oxygenated fatty acid |

| SPOT | San Pedro Ocean Time Series |

| 6-oxoHME | 6-oxo-hexadecaenoic acid |

| 9-EpHTrE | 9-epoxy-hexadecatrienoic acid |

| 9-HHTE | 9-hydroxy-hexadecatetraenoic acid |

| 9-HODE | 9-hydroxy-octadecadienoic acid |

| 5-HpEPE | 5-hydroperoxy-eicosapentaenoic acid |

| 15-HpEPE | 15-hydroperoxy-eicosapentaenoic acid |

| 5-HEPE | 5-hydroxy-eicosapentaenoic acid |

| 11,12-EpETE | 11,12-epoxy-eicosatetraenoic acid |

| 15-HpETE | 15-hydroperoxy-eiocsatetraenoic acid |

| 6-keto-PGE1 | 6-ketoprostaglandin E1 |

| 15-deoxy-PGD2 | 15-deoxyprostaglandin D2 |

| HTrA | Hexadecatrienoic acid |

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoic acid |

| PLSDA | Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| FFA | Free fatty acid |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

References

- Field, C.B.; Behrenfeld, M.J.; Randerson, J.T.; Falkowski, P. Primary Production of the Biosphere: Integrating Terrestrial and Oceanic Components. Science 1998, 281, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falkowski, P.G.; Barber, R.T.; Smetacek, V. Biogeochemical Controls and Feedbacks on Ocean Primary Production. Science 1998, 281, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tréguer, P.; Bowler, C.; Moriceau, B.; Dutkiewicz, S.; Gehlen, M.; Aumont, O.; Bittner, L.; Dugdale, R.; Finkel, Z.; Iudicone, D.; et al. Influence of Diatom Diversity on the Ocean Biological Carbon Pump. Nat. Geosci. 2018, 11, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Gruber, N.; Dunne, J.P.; Sarmiento, J.L.; Armstrong, R.A. Diagnosing the Contribution of Phytoplankton Functional Groups to the Production and Export of Particulate Organic Carbon, CaCO3, and Opal from Global Nutrient and Alkalinity Distributions. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2006, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, A.; Goldthwait, S.; Passow, U.; Alldredge, A. Temporal Decoupling of Carbon and Nitrogen Dynamics in a Mesocosm Diatom Bloom. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2002, 47, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, D.C.O. Dissolved Organic Matter (DOM) Release by Phytoplankton in the Contemporary and Future Ocean. Eur. J. Phycol. 2014, 49, 20–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Vallet, M.; Pohnert, G. Temporal and Spatial Signaling Mediating the Balance of the Plankton Microbiome. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2022, 14, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribalet, F.; Berges, J.A.; Ianora, A.; Casotti, R. Growth Inhibition of Cultured Marine Phytoplankton by Toxic Algal-Derived Polyunsaturated Aldehydes. Aquat. Toxicol. 2007, 85, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralto, A.; Barone, G.; Romano, G.; Poulet, S.A.; Ianora, A.; Russo, G.L.; Buttino, I.; Mazzarella, G.; Laabir, M.; Cabrini, M.; et al. The Insidious Effect of Diatoms on Copepod Reproduction. Nature 1999, 402, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.D.; Edwards, B.R.; Beaudoin, D.J.; Van Mooy, B.A.S.; Vardi, A. Nitric Oxide Mediates Oxylipin Production and Grazing Defense in Diatoms. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 629–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianora, A.; Miralto, A.; Poulet, S.A.; Carotenuto, Y.; Buttino, I.; Romano, G.; Casotti, R.; Pohnert, G.; Wichard, T.; Colucci-D’Amato, L.; et al. Aldehyde Suppression of Copepod Recruitment in Blooms of a Ubiquitous Planktonic Diatom. Nature 2004, 429, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribalet, F.; Intertaglia, L.; Lebaron, P.; Casotti, R. Differential Effect of Three Polyunsaturated Aldehydes on Marine Bacterial Isolates. Aquat. Toxicol. 2008, 86, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B.R.; Bidle, K.D.; Van Mooy, B.A.S. Dose-Dependent Regulation of Microbial Activity on Sinking Particles by Polyunsaturated Aldehydes: Implications for the Carbon Cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 5909–5914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, N.; Rettner, J.; Werner, M.; Werz, O.; Pohnert, G. Algal Oxylipins Mediate the Resistance of Diatoms against Algicidal Bacteria. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardi, A.; Formiggini, F.; Casotti, R.; Martino, A.D.; Ribalet, F.; Miralto, A.; Bowler, C. A Stress Surveillance System Based on Calcium and Nitric Oxide in Marine Diatoms. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, B.R.; Thamatrakoln, K.; Fredricks, H.F.; Bidle, K.D.; Van Mooy, B.A.S. Viral Infection Leads to a Unique Suite of Allelopathic Chemical Signals in Three Diatom Host–Virus Pairs. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohnert, G. Wound-Activated Chemical Defense in Unicellular Planktonic Algae. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 4352–4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribalet, F.; Wichard, T.; Pohnert, G.; Ianora, A.; Miralto, A.; Casotti, R. Age and Nutrient Limitation Enhance Polyunsaturated Aldehyde Production in Marine Diatoms. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 2059–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidoudez, C.; Pohnert, G. Growth Phase-Specific Release of Polyunsaturated Aldehydes by the Diatom Skeletonema marinoi. J. Plankton Res. 2008, 30, 1305–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, Q.P.; Ge, Z.; Huang, B.; Dong, C. Impacts of Biogenic Polyunsaturated Aldehydes on Metabolism and Community Composition of Particle-Attached Bacteria in Coastal Hypoxia. Biogeosciences 2021, 18, 1049–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettner, J.; Werner, M.; Meyer, N.; Werz, O.; Pohnert, G. Survey of the C20 and C22 Oxylipin Family in Marine Diatoms. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 828–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauritano, C.; Romano, G.; Roncalli, V.; Amoresano, A.; Fontanarosa, C.; Bastianini, M.; Braga, F.; Carotenuto, Y.; Ianora, A. New Oxylipins Produced at the End of a Diatom Bloom and Their Effects on Copepod Reproductive Success and Gene Expression Levels. Harmful Algae 2016, 55, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, E.; d’Ippolito, G.; Fontana, A.; Sarno, D.; D’Alelio, D.; Busseni, G.; Ianora, A.; von Elert, E.; Carotenuto, Y. Density-Dependent Oxylipin Production in Natural Diatom Communities: Possible Implications for Plankton Dynamics. ISME J. 2020, 14, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreiro, A.; Carotenuto, Y.; Lamari, N.; Esposito, F.; D’Ippolito, G.; Fontana, A.; Romano, G.; Ianora, A.; Miralto, A.; Guisande, C. Diatom Induction of Reproductive Failure in Copepods: The Effect of PUAs versus Non Volatile Oxylipins. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2011, 401, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianora, A.; Bastianini, M.; Carotenuto, Y.; Casotti, R.; Roncalli, V.; Miralto, A.; Romano, G.; Gerecht, A.; Fontana, A.; Turner, J.T. Non-Volatile Oxylipins Can Render Some Diatom Blooms More Toxic for Copepod Reproduction. Harmful Algae 2015, 44, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzè, G.; Pierson, J.J.; Stoecker, D.K.; Lavrentyev, P.J. Diatom-Produced Allelochemicals Trigger Trophic Cascades in the Planktonic Food Web. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2018, 63, 1093–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, D.J.; Kilham, S.S.; Theriot, E. Differences in Silica Content between Marine and Freshwater Diatoms. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1989, 34, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooistra, W.H.C.F.; Sarno, D.; Balzano, S.; Gu, H.; Andersen, R.A.; Zingone, A. Global Diversity and Biogeography of Skeletonema Species (Bacillariophyta). Protist 2008, 159, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarno, D.; Kooistra, W.H.C.F.; Medlin, L.K.; Percopo, I.; Zingone, A. Diversity in the Genus Skeletonema (Bacillariophyceae). Ii. an Assessment of the Taxonomy of S. costatum-like Species with the Description of Four New Species. J. Phycol. 2005, 41, 151–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, O.G.; Ponomareva, A.A.; Turanov, S.V.; Dutova, D.I. Morphological and Genetic Variability of Skeletonema dohrnii and Skeletonema Japonicum (Bacillariophyta) from the Northwestern Sea of Japan. Phycologia 2019, 58, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Rao, D.V.S.; Mann, K.H.; Li, W.K.W.; Harrison, W.G. Effects of Silicate Limitation on Production of Domoic Acid, a Neurotoxin, by the Diatom Pseudo-nitzschia multiseries. I. Batch culture studies. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1996, 131, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, A.; Harrison, P.J. Coupled Changes in the Cell Morphology and Elemental (C, N, and Si) Composition of the Pennate Diatom Pseudo-Nitzschia Due to Iron Deficiency. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2007, 52, 2270–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Subba Rao, D.V.; Mann, K.H. Changes in Domoic Acid Production and Cellular Chemical Composition of the Toxigenic Diatom Pseudo-Nitzschia Multiseries Under Phosphate Limitation. J. Phycol. 1996, 32, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainer, V.L.; Bates, S.S.; Lundholm, N.; Thessen, A.E.; Cochlan, W.P.; Adams, N.G.; Trick, C.G. Pseudo-nitzschia Physiological Ecology, Phylogeny, Toxicity, Monitoring and Impacts on Ecosystem Health. Harmful Algae 2012, 14, 271–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zheng, T.; Lundholm, N.; Huang, X.; Jiang, X.; Li, A.; Li, Y. Chemical and Morphological Defenses of Pseudo-nitzschia multiseries in Response to Zooplankton Grazing. Harmful Algae 2021, 104, 102033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, R.; Moore, S.K.; Trainer, V.L.; Bill, B.D.; Fischer, A.; Batten, S. Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Pseudo-nitzschia Genetic Diversity in the North Pacific Ocean from the Continuous Plankton Recorder Survey. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2018, 606, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzezinski, M.A. The Si:C:N ratio of marine diatoms: Interspecific variability and the effect of some environmental variables. J. Phycol. 1985, 21, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Yao, Y. Nutrient Compositions of Cultured Thalassiosira rotula and Skeletonema costatum from Jiaozhou Bay. In Studies of the Biogeochemistry of Typical Estuaries and Bays in China; Shen, Z., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2020; pp. 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, K.A.; Rignanese, D.R.; Olson, R.J.; Rynearson, T.A. Molecular Subdivision of the Marine Diatom Thalassiosira rotulain Relation to Geographic Distribution, Genome Size, and Physiology. BMC Evol. Biol. 2012, 12, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.Q.; Milke, F.; Niggemann, J.; Simon, M. The Diatom Thalassiosira Rotula Induces Distinct Growth Responses and Colonization Patterns of Roseobacteraceae, Flavobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 25, 3536–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, D.; Kooistra, W.H.C.F.; Sarno, D.; Gaonkar, C.C.; Piredda, R. Global Distribution and Diversity of Chaetoceros (Bacillariophyta, Mediophyceae): Integration of Classical and Novel Strategies. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, J.R.; Edwards, B.R.; Fredricks, H.F.; Van Mooy, B.A.S. LOBSTAHS: An Adduct-Based Lipidomics Strategy for Discovery and Identification of Oxidative Stress Biomarkers. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 7154–7162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugawa, H.; Cajka, T.; Kind, T.; Ma, Y.; Higgins, B.; Ikeda, K.; Kanazawa, M.; VanderGheynst, J.; Fiehn, O.; Arita, M. MS-DIAL: Data-Independent MS/MS Deconvolution for Comprehensive Metabolome Analysis. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barofsky, A.; Pohnert, G. Biosynthesis of Polyunsaturated Short Chain Aldehydes in the Diatom Thalassiosira Rotula. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 1017–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Ippolito, G.; Cutignano, A.; Briante, R.; Febbraio, F.; Cimino, G.; Fontana, A. New C16 Fatty-Acid-Based Oxylipin Pathway in the Marine Diatom Thalassiosira Rotula. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005, 3, 4065–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wear, E.K.; Carlson, C.A.; Windecker, L.A.; Brzezinski, M.A. Roles of Diatom Nutrient Stress and Species Identity in Determining the Short- and Long-Term Bioavailability of Diatom Exudates to Bacterioplankton. Mar. Chem. 2015, 177, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruocco, N.; Albarano, L.; Esposito, R.; Zupo, V.; Costantini, M.; Ianora, A. Multiple Roles of Diatom-Derived Oxylipins within Marine Environments and Their Potential Biotechnological Applications. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Yu, R.; Grabe, V.; Sommermann, T.; Werner, M.; Vallet, M.; Zerfaß, C.; Werz, O.; Pohnert, G. Bacteria Modulate Microalgal Aging Physiology through the Induction of Extracellular Vesicle Production to Remove Harmful Metabolites. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 2356–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, H.; Kong, T.K.; Rosengarten, G. Diffusion through Diatom Nanopores. J. Nano Res. 2009, 7, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Jézéquel, V.; Hildebrand, M.; Brzezinski, M.A. Silicon Metabolism in Diatoms: Implications for Growth. J. Phycol. 2000, 36, 821–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, H.M.; Brzezinski, M.A.; Krause, J.W. Diatom Populations in an Upwelling Environment Decrease Silica Content to Avoid Growth Limitation. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 20, 4184–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Ma, J.; Zhong, Z.; Liu, H.; Miao, A.; Zhu, X.; Pan, K. Silicon Limitation Impairs the Tolerance of Marine Diatoms to Pristine Microplastics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 3291–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ippolito, G.; Lamari, N.; Montresor, M.; Romano, G.; Cutignano, A.; Gerecht, A.; Cimino, G.; Fontana, A. 15S-Lipoxygenase Metabolism in the Marine Diatom Pseudo-nitzschia delicatissima. New Phytol. 2009, 183, 1064–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jónasdóttir, S.H. Fatty Acid Profiles and Production in Marine Phytoplankton. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, E.; Cosnahan, R.K.; Wu, M.; Gadila, S.K.; Quick, E.B.; Mobley, J.A.; Campos-Gómez, J. Oxylipins Mediate Cell-to-Cell Communication in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, Z. Quorum Sensing-Mediated Lipid Oxidation Further Regulating the Environmental Adaptability of Aspergillus ochraceus. Metabolites 2023, 13, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, S.A.; Parker, M.S.; Armbrust, E.V. Interactions between Diatoms and Bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012, 76, 667–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revol-Cavalier, J.; Quaranta, A.; Newman, J.W.; Brash, A.R.; Hamberg, M.; Wheelock, C.E. The Octadecanoids: Synthesis and Bioactivity of 18-Carbon Oxygenated Fatty Acids in Mammals, Bacteria, and Fungi. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 1–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, I.; Heydeck, D.; Hofheinz, K.; Roffeis, J.; O’Donnell, V.B.; Kuhn, H.; Walther, M. Molecular Enzymology of Lipoxygenases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2010, 503, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcomer, M.E.; Brash, A.R. The Structural Basis for Specificity in Lipoxygenase Catalysis. Protein Sci. 2015, 24, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Ippolito, G.; Nuzzo, G.; Sardo, A.; Manzo, E.; Gallo, C.; Fontana, A. Chapter Four—Lipoxygenases and Lipoxygenase Products in Marine Diatoms. In Methods in Enzymology; Moore, B.S., Ed.; Marine Enzymes and Specialized Metabolism—Part B; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Volume 605, pp. 69–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichard, T.; Poulet, S.A.; Halsband-Lenk, C.; Albaina, A.; Harris, R.; Liu, D.; Pohnert, G. Survey of the Chemical Defence Potential of Diatoms: Screening of Fifty Species for α,β,γ,δ-Unsaturated Aldehydes. J. Chem. Ecol. 2005, 31, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamari, N.; Ruggiero, M.V.; d’Ippolito, G.; Kooistra, W.H.C.F.; Fontana, A.; Montresor, M. Specificity of Lipoxygenase Pathways Supports Species Delineation in the Marine Diatom Genus Pseudo-nitzschia. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerecht, A.; Romano, G.; Ianora, A.; d’Ippolito, G.; Cutignano, A.; Fontana, A. Plasticity of Oxylipin Metabolism Among Clones of the Marine Diatom Skeletonema marinoi (Bacillariophyceae). J. Phycol. 2011, 47, 1050–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, D.; Bonora, S.; D’Orsi, I.; D’Alelio, D.; Facchiano, A. Structural and Functional Characterization of Lipoxygenases from Diatoms by Bioinformatics and Modelling Studies. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, Y.; Tanaka, T. Molecular Insights into Lipoxygenases in Diatoms Based on Structure Prediction: A Pioneering Study on Lipoxygenases Found in Pseudo-nitzschia arenysensis and Fragilariopsis cylindrus. Mar. Biotechnol. 2022, 24, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatino, V.; Orefice, I.; Marotta, P.; Ambrosino, L.; Chiusano, M.L.; d’Ippolito, G.; Romano, G.; Fontana, A.; Ferrante, M.I. Silencing of a Pseudo-nitzschia arenysensis Lipoxygenase Transcript Leads to Reduced Oxylipin Production and Impaired Growth. New Phytol. 2022, 233, 809–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Yoneda, K.; Maeda, Y. Lipid Metabolism in Diatoms. In The Molecular Life of Diatoms; Falciatore, A., Mock, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 493–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohnert, G. Phospholipase A2 Activity Triggers the Wound-Activated Chemical Defense in the Diatom Thalassiosira rotula. Plant Physiol. 2002, 129, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, J.W.; Schulz, I.K.; Rowe, K.A.; Dobbins, W.; Winding, M.H.S.; Sejr, M.K.; Duarte, C.M.; Agustí, S. Silicic Acid Limitation Drives Bloom Termination and Potential Carbon Sequestration in an Arctic Bloom. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, B.; Thamatrakoln, K.; Kranzler, C.F.; Ossolinski, J.; Fredricks, H.; Johnson, M.D.; Krause, J.W.; Bidle, K.D.; Mooy, B.A.S.V. Viral Infection Induces Oxylipin Chemical Signaling at the End of a Summer Upwelling Bloom: Implications for Carbon Cycling. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestra, C.; Alonso-Sáez, L.; Gasol, J.M.; Casotti, R. Group-Specific Effects on Coastal Bacterioplankton of Polyunsaturated Aldehydes Produced by Diatoms. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 2011, 63, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrentyev, P.J.; Franzè, G.; Pierson, J.J.; Stoecker, D.K. The Effect of Dissolved Polyunsaturated Aldehydes on Microzooplankton Growth Rates in the Chesapeake Bay and Atlantic Coastal Waters. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 2834–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adusumilli, R.; Mallick, P. Data Conversion with ProteoWizard msConvert. In Proteomics: Methods and Protocols; Comai, L., Katz, J.E., Mallick, P., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 339–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, C.; Tautenhahn, R.; Böttcher, C.; Larson, T.R.; Neumann, S. CAMERA: An Integrated Strategy for Compound Spectra Extraction and Annotation of Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry Data Sets. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.; Want, E.J.; O’Maille, G.; Abagyan, R.; Siuzdak, G. XCMS: Processing Mass Spectrometry Data for Metabolite Profiling Using Nonlinear Peak Alignment, Matching, and Identification. Anal. Chem. 2006, 78, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitzer, P.; Bennett, B.; Melamud, E. MAVEN2: An Updated Open-Source Mass Spectrometry Exploration Platform. Metabolites 2022, 12, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Z.; Zhou, G.; Ewald, J.; Chang, L.; Hacariz, O.; Basu, N.; Xia, J. Using MetaboAnalyst 5.0 for LC–HRMS Spectra Processing, Multi-Omics Integration and Covariate Adjustment of Global Metabolomics Data. Nat. Protoc. 2022, 17, 1735–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Diatom | Label | Morphology | Cell Length (µm) | Silicon Content (pmol/cell) | Si:C | Distribution | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletonema japonicum | SJ | Centric | 5.3–5.5 | 0.03–3.40 a | 0.07–0.11 a | Cold temperate coasts and upwelling zones | [27,28,29,30] |

| Pseudo-nitzschia multiseries | PNM | Pennate | 50–140 | 1.07, 1.9 b | 0.16, 0.21 | Coasts alongside the NW Pacific, NE Atlantic, and Mediterranean | [31,32,33,34,35,36] |

| Thalassiosira rotula | TR | Centric | 10.5–65.8 | 0.07 b, 0.09 b | 0.09 | North Pacific and Atlantic, Mediterranean, Southern Ocean | [37,38,39,40] |

| Chaetoceros sp. | SPOT2312 | Centric | 0.12–7.30 c | 0.09–0.15 c | Global | [37,41] | |

| Unidentified | SPOT2302 | Centric |

| Compound | Acronym | LOBSTAHS Annotation | Matched Fragments | LOBSTAHS (m/z) | MSDIAL (m/z) | LOBSTAHS Retention Time (mins) | MSDIAL Retention Time (mins) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFA 12:2 +1O | 211.13397 | 211.13397 | 14.90 | 14.94 | |||

| FFA 12:2 +1O | 211.13398 | 211.13403 | 14.56 | 14.55 | |||

| FFA 12:3 +2O | 225.11320 | 225.11342 | 7.88 | 7.87 | |||

| FFA 12:3 +2O | 225.11324 | 225.11313 | 5.91 | 5.90 | |||

| FFA 13:2 +1O | 225.14962 | 225.14963 | 13.21 | 13.25 | |||

| FFA 13:2 +2O | 241.14466 | 241.14436 | 11.35 | 11.32 | |||

| 9-hydroxy-tetradeca-7-enoic acid | FFA 14:1 +1O | 4 | 241.18095 | 241.18069 | 18.55 | 18.37 | |

| 9-hydroxy-tetradeca-7-enoic acid | FFA 14:1 +1O | 3 | 241.18095 | 241.18074 | 18.79 | 18.86 | |

| FFA 14:1 +1O | 241.18097 | 241.18097 | 17.89 | 17.85 | |||

| FFA 15:2 +1O | 253.18091 | 253.18076 | 15.73 | 15.74 | |||

| FFA 15:1 +1O | 255.19631 | 255.19649 | 16.76 | 16.80 | |||

| 9-hydroxy-pentadeca-10-enoic acid | FFA 15:1 +1O | 3 | 255.19649 | 255.19685 | 19.90 | 19.74 | |

| FFA 15:1 +1O | 255.19668 | 255.19658 | 20.10 | 20.12 | |||

| FFA 15:1 +1O | 255.19674 | 255.19664 | 19.28 | 19.31 | |||

| 9-hydroxy-hexadecatetraenoic acid | 9-HHTE | FFA 16:4 +1O | 3 | 263.16516 | 263.16525 | 15.31 | 15.46 |

| FFA 18:5 +1O | 289.18101 | 289.18088 | 20.14 | 20.15 | |||

| FFA 18:4 +1O | 291.19644 | 291.19653 | 19.93 | 19.91 | |||

| FFA 18:4 +1O | 291.19675 | 291.19672 | 21.77 | 21.77 | |||

| FFA 18:2 +1O | 295.22768 | 295.22784 | 20.61 | 20.56 | |||

| FFA 18:2 +1O | 295.22769 | 295.22751 | 20.31 | 20.29 | |||

| 9-hydroxy-octadecadienoic acid | 9-HODE | FFA 18:2 +1O | 3 | 295.22776 | 295.22739 | 19.08 | 19.06 |

| FFA 18:1 +1O | 297.24343 | 297.24298 | 21.79 | 21.77 | |||

| 11,12-epoxy-eicosatetraenoic acid | 11,12-EpETE | FFA 20:5 +1O | 6 | 317.21215 | 317.21219 | 18.13 | 18.30 |

| 6-ketoprostaglandin E1 | 6-keto-PGE1 | FFA 20:4 +4O | 3 | 367.21191 | 367.21179 | 12.90 | 12.90 |

| FFA 22:6 +3O | 375.21731 | 375.21729 | 18.14 | 18.17 | |||

| FFA 22:4 +4O | 395.24372 | 395.24326 | 15.17 | 15.19 | |||

| FFA 16:1 +1O | 269.21213 | 18.69 | |||||

| FFA 18:3 +3O | 325.20192 | 13.40 | |||||

| 9-epoxy-hexadecatrienoic acid | 9-epHTrE | 6 | 263.16525 | 15.97 | |||

| 6-oxo-hexadecaenoic acid | 6-oxoHME | 5 | 267.19632 | 19.49 | |||

| 15-deoxyprostaglandin D2 | 15-deoxy-PGD2 | 3 | 333.20682 | 15.74 | |||

| 15-hydroperoxy-eicosapentaenoic acid | 15-HpEPE | 18 | 315.19614 | 18.48 | |||

| 5-hydroperoxy-eicosapentaenoic acid | 5-HpEPE | 10 | 315.1965 | 18.96 | |||

| 5-hydroxy-eicosapentaenoic acid | 5-HEPE | 6 | 317.21188 | 18.78 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ulloa, I.; Hwang, J.; Johnson, M.D.; Edwards, B.R. Lipidomic Screening of Marine Diatoms Reveals Release of Dissolved Oxylipins Associated with Silicon Limitation and Growth Phase. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23110424

Ulloa I, Hwang J, Johnson MD, Edwards BR. Lipidomic Screening of Marine Diatoms Reveals Release of Dissolved Oxylipins Associated with Silicon Limitation and Growth Phase. Marine Drugs. 2025; 23(11):424. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23110424

Chicago/Turabian StyleUlloa, Imanol, Jiwoon Hwang, Matthew D. Johnson, and Bethanie R. Edwards. 2025. "Lipidomic Screening of Marine Diatoms Reveals Release of Dissolved Oxylipins Associated with Silicon Limitation and Growth Phase" Marine Drugs 23, no. 11: 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23110424

APA StyleUlloa, I., Hwang, J., Johnson, M. D., & Edwards, B. R. (2025). Lipidomic Screening of Marine Diatoms Reveals Release of Dissolved Oxylipins Associated with Silicon Limitation and Growth Phase. Marine Drugs, 23(11), 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23110424