Isolation and Characterization of Anti-Adenoviral Secondary Metabolites from Marine Actinobacteria

Abstract

:1. Introduction

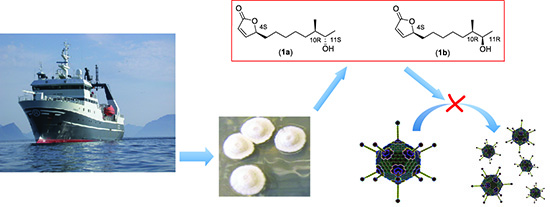

2. Results and Discussion

2.2. Isolation and Characterization of Butenolide Analogs

2.2.1. Investigation of the Optimal Time of Cultivation for Production of the Butenolides 1a and 1b

2.2.2. Cultivation of Streptomyces sp. AW28M48 and Isolation of Butenolide Analogs

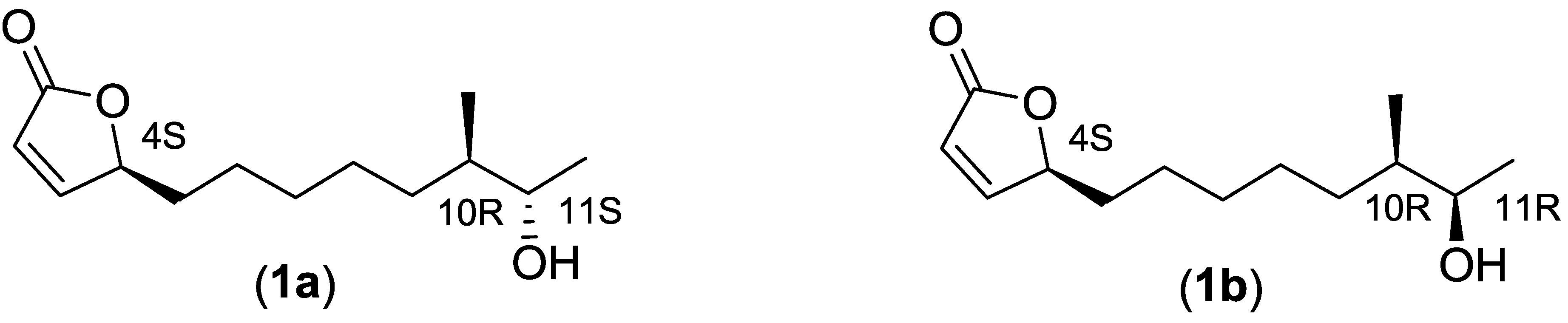

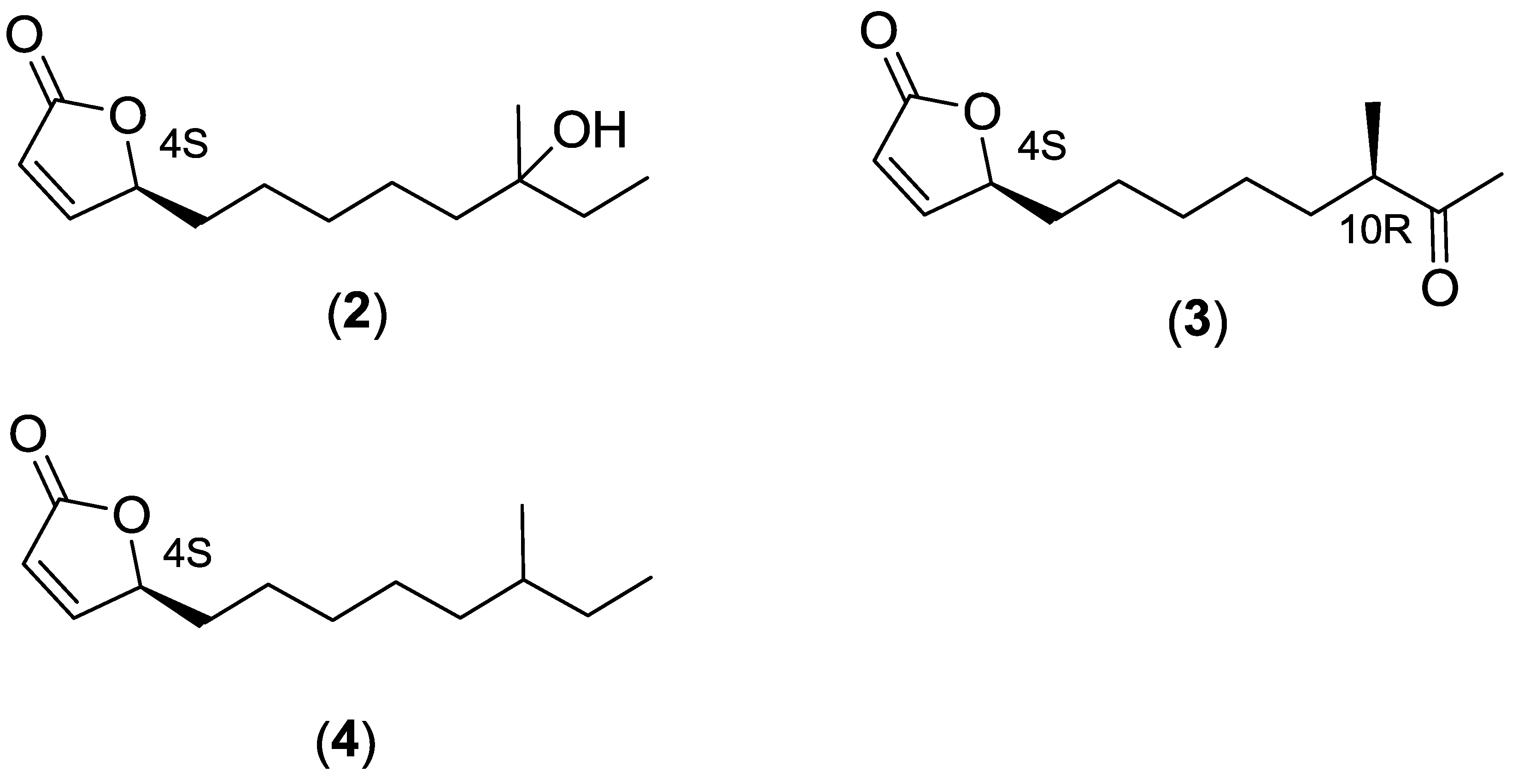

2.2.3. Structure Elucidation of the Butenolide Analogs

| Compound | Optical Rotations | Optical Rotations from Previous Publications |

|---|---|---|

| 1a and 1b (1:1 mixture) | +80.8° (c 1.15, MeOH) | +84.5° (c 0.119, MeOH)(natural) [15] |

| 1a (4S10R11S) | +74.4° (c 0.926, MeOH) (85% de) | +70.9° (c 0.12, MeOH)(synth.) [17] |

| +78° (c 0.1, MeOH)(synth.) [18] | ||

| 1b (4S10R11R) | +64.3° (c 0.14, MeOH)(synth.) [19] | |

| 2 | +66.5° (c 0.927, MeOH) | +44° (c 0.072, MeOH)(natural) [15] |

| 3 (4S10R) | +48.8° (c 1.475, MeOH) | +45° (c 0.119, MeOH)(natural) [15] |

| +49.4° (c 0.175, MeOH)(synth.) [19] | ||

| 3 (4S10S) | +73.0° (c 0.12, MeOH)(synth.) [19] | |

| 4 | +58° (c 1.033, MeOH) |

| Position | 1a | 1a [17] | 1a + (1b) | 1b [19] | 2 | 2 [15] | 3 | 3 [19] | 4 | 4 [16] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 CO | 173.12 | 173.19 | 173.12 | 173.14 | 173.1 | 173.2 | 173.07 | 173.09 | 173.2 | 173.1 |

| 2 CH | 121.57 | 121.54 | 121.57 | 121.54 | 121.6 | 121.6 | 121.59 | 121.59 | 121.5 | 121.5 |

| 3 CH | 156.20 | 156.30 | 156.3 | 156.23 | 156.2 | 156.2 | 156.16 | 156.17 | 156.3 | 156.3 |

| 4 CH | 83.36 | 83.41 | 83.36 | 83.39 | 83.3 | 83.4 | 83.29 | 83.29 | 83.4 | 83.4 |

| 5 CH2 | 33.16 | 33.15 | 33.16 | 33.15 | 33.1 | 33.1 | 33.05 | 33.06 | 33.2 | 33.2 |

| 6 CH2 | 24.94 | 24.95 | 24.96 | 24.95 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 24.79 | 24.79 | 25.0 | 25.0 |

| 7 CH2 | 29.60 | 29.60 | 29.60 | 29.60 | 29.9 | 29.9 | 29.30 | 29.30 | 29.6 | 29.6 |

| 8 CH2 | 26.97 | 26.98 | 27.11 | 27.10 | 23.6 | 23.6 | 26.94 | 26.96 | 26.8 | 26.8 |

| 9 CH2 | 32.33 | 32.34 | 32.43 | 32.41 | 41.1 | 41.1 | 32.62 | 32.62 | 36.4 | 36.4 |

| 10 | 39.98 CH | 39.97 CH | 39.68 CH | 39.67 CH | 72.8 Cq | 72.9 Cq | 47.10 CH | 47.11 CH | 34.3 CH | 34.3 CH |

| 11 | 71.71 CH | 71.70 CH | 71.29 CH | 71.30 CH | 34.3 CH2 | 34.3 CH2 | 212.77 CO | 212.80 CO | 29.4 CH2 | 29.4 CH2 |

| 12 CH3 | 19.51 | 19.49 | 20.26 | 20.25 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 28.01 | 28.03 | 11.4 | 11.3 |

| 13 CH3 | 14.58 | 14.57 | 14.12 | 14.11 | 26.4 | 26.4 | 16.28 | 16.29 | 19.2 | 19.1 |

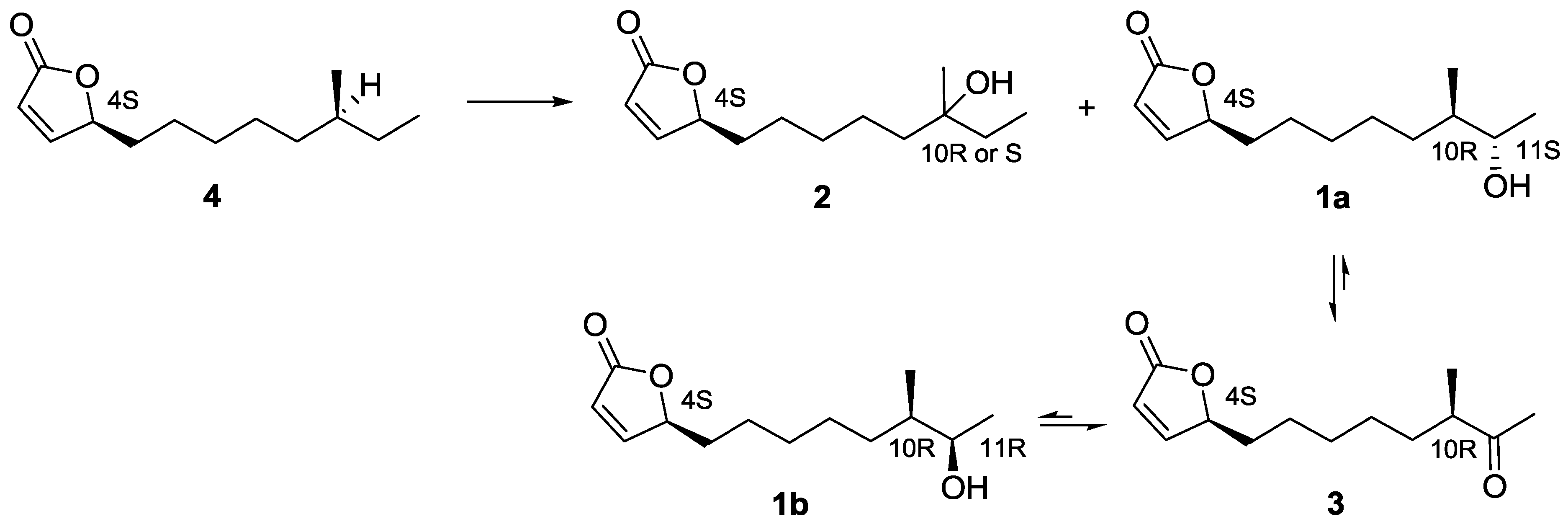

2.3. Proposed Biosynthetic Pathway of Butenolide 1–4

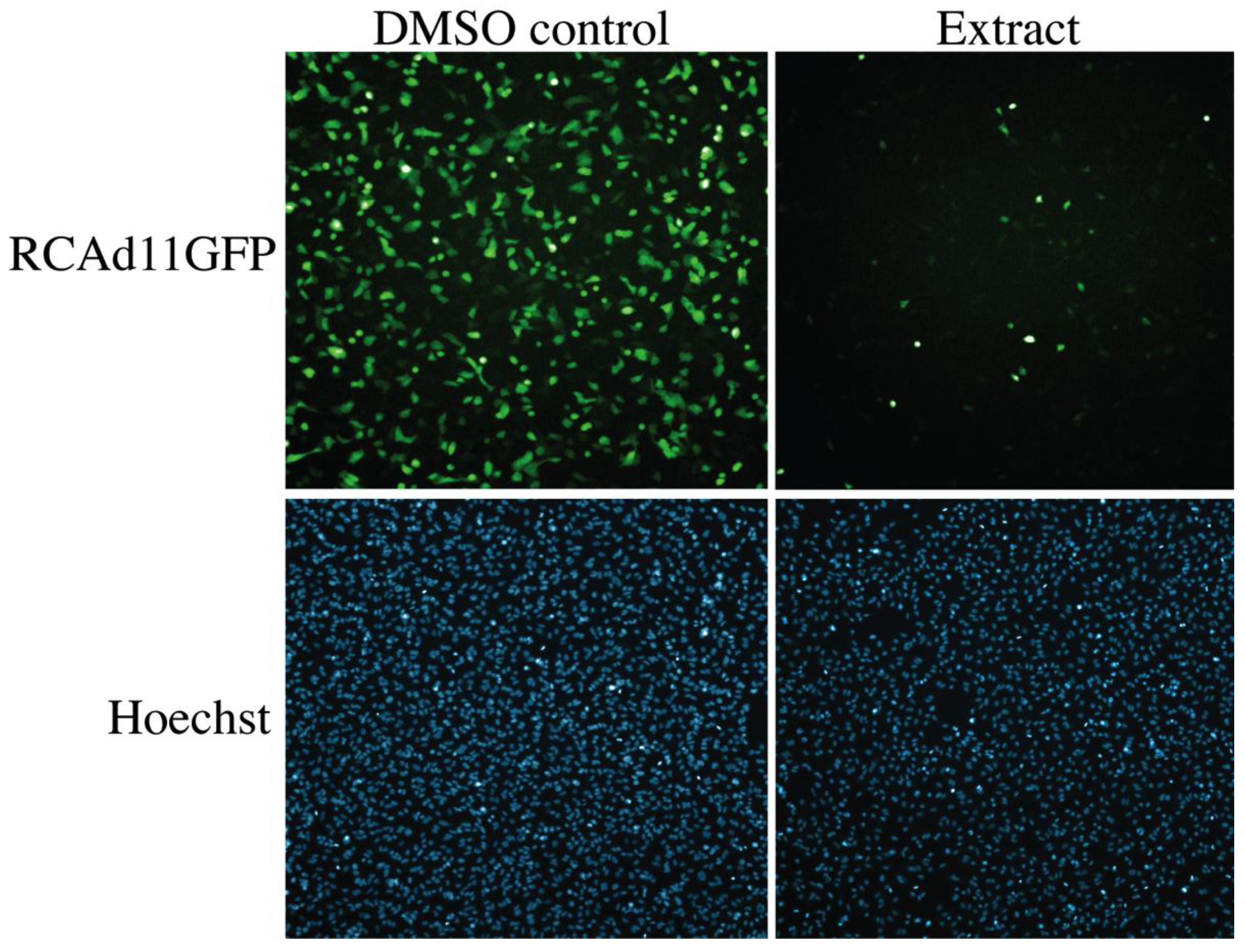

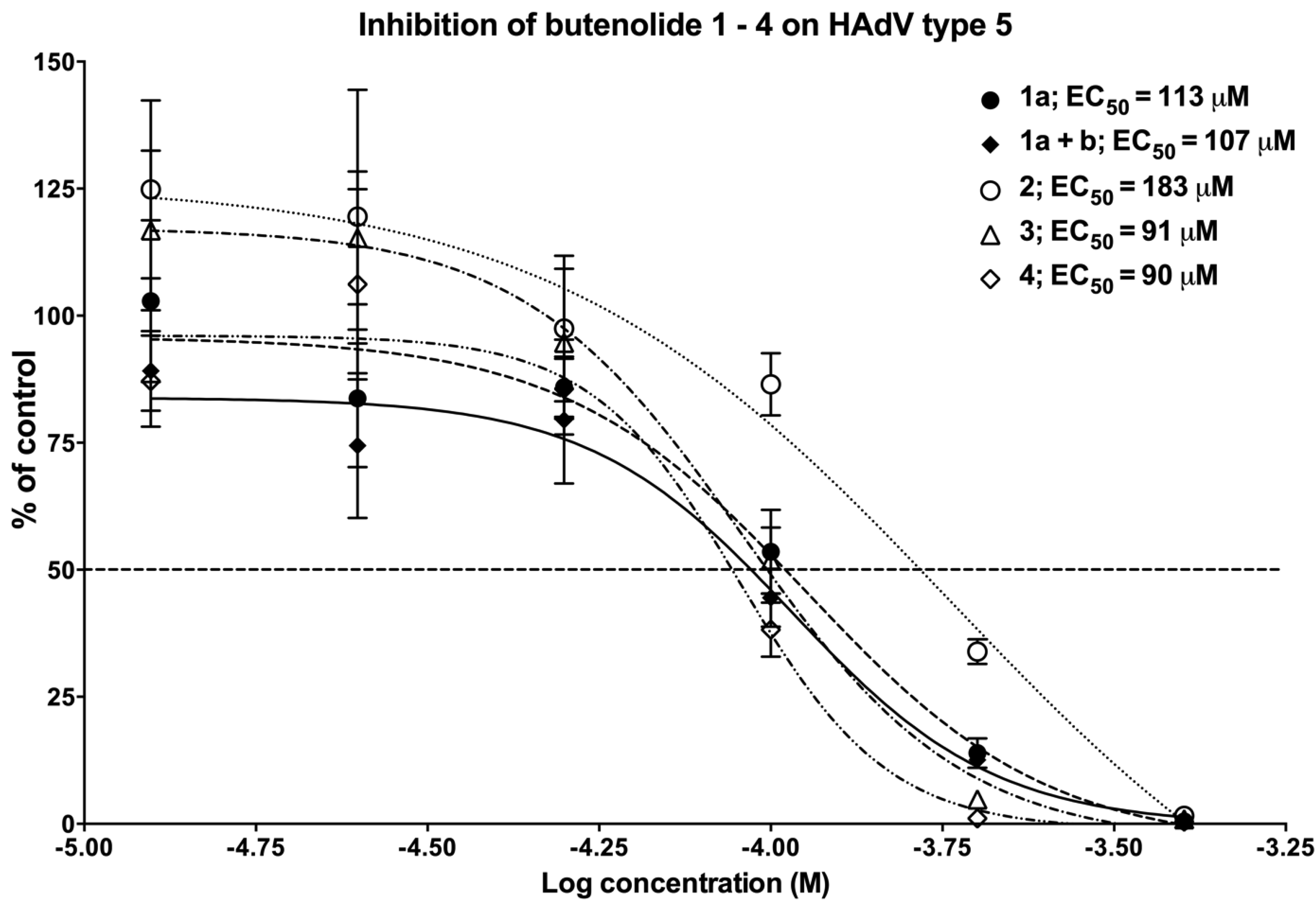

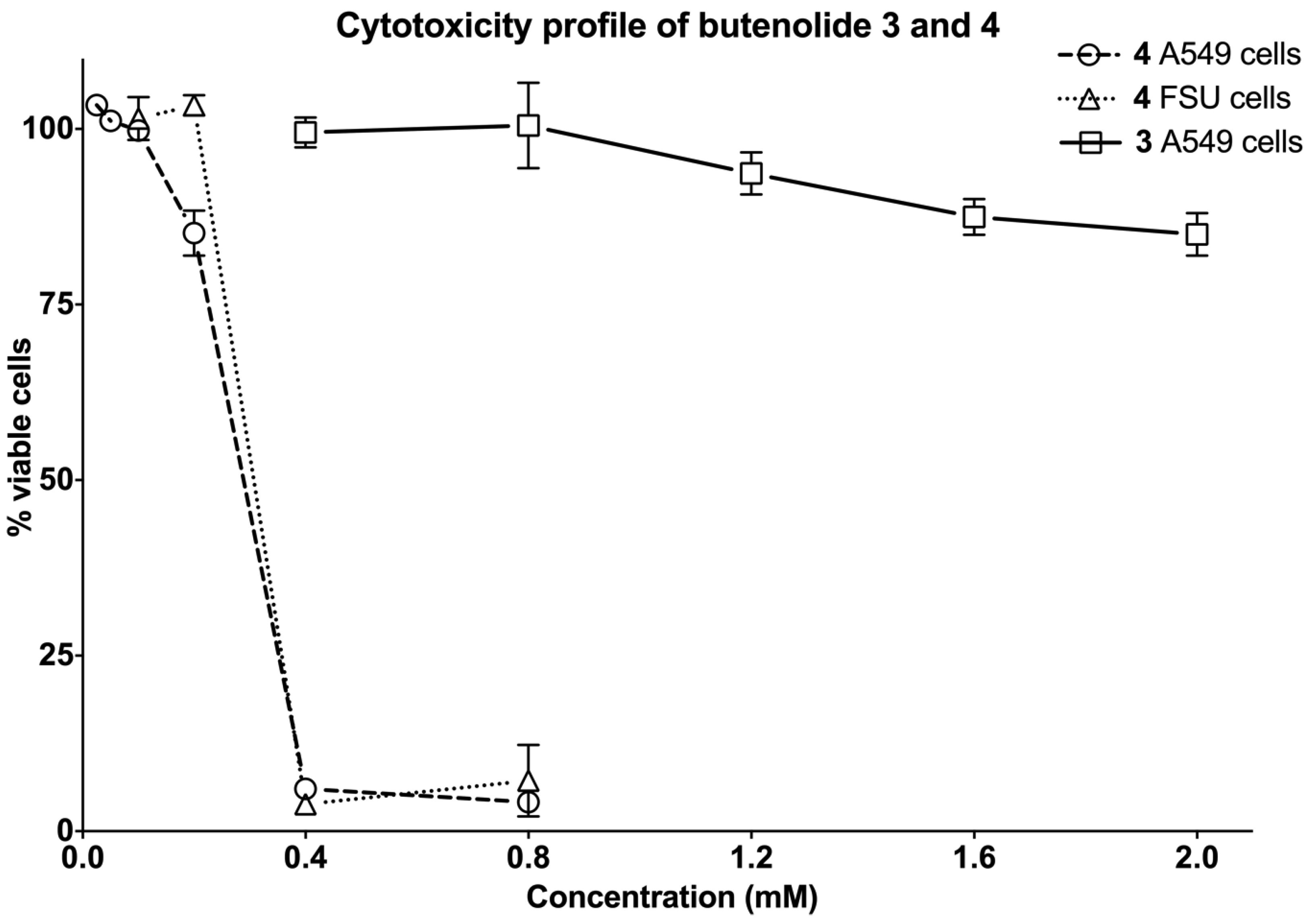

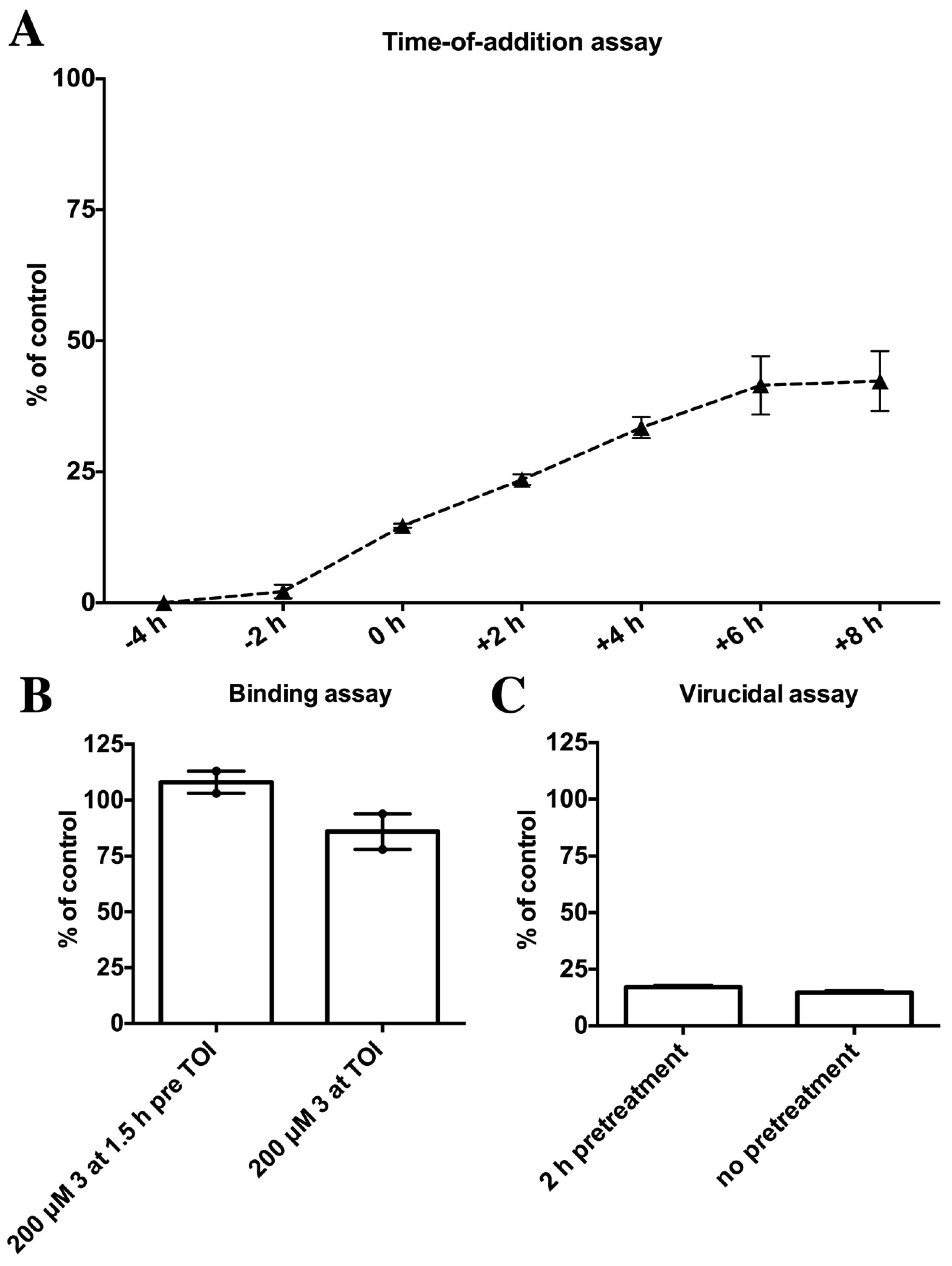

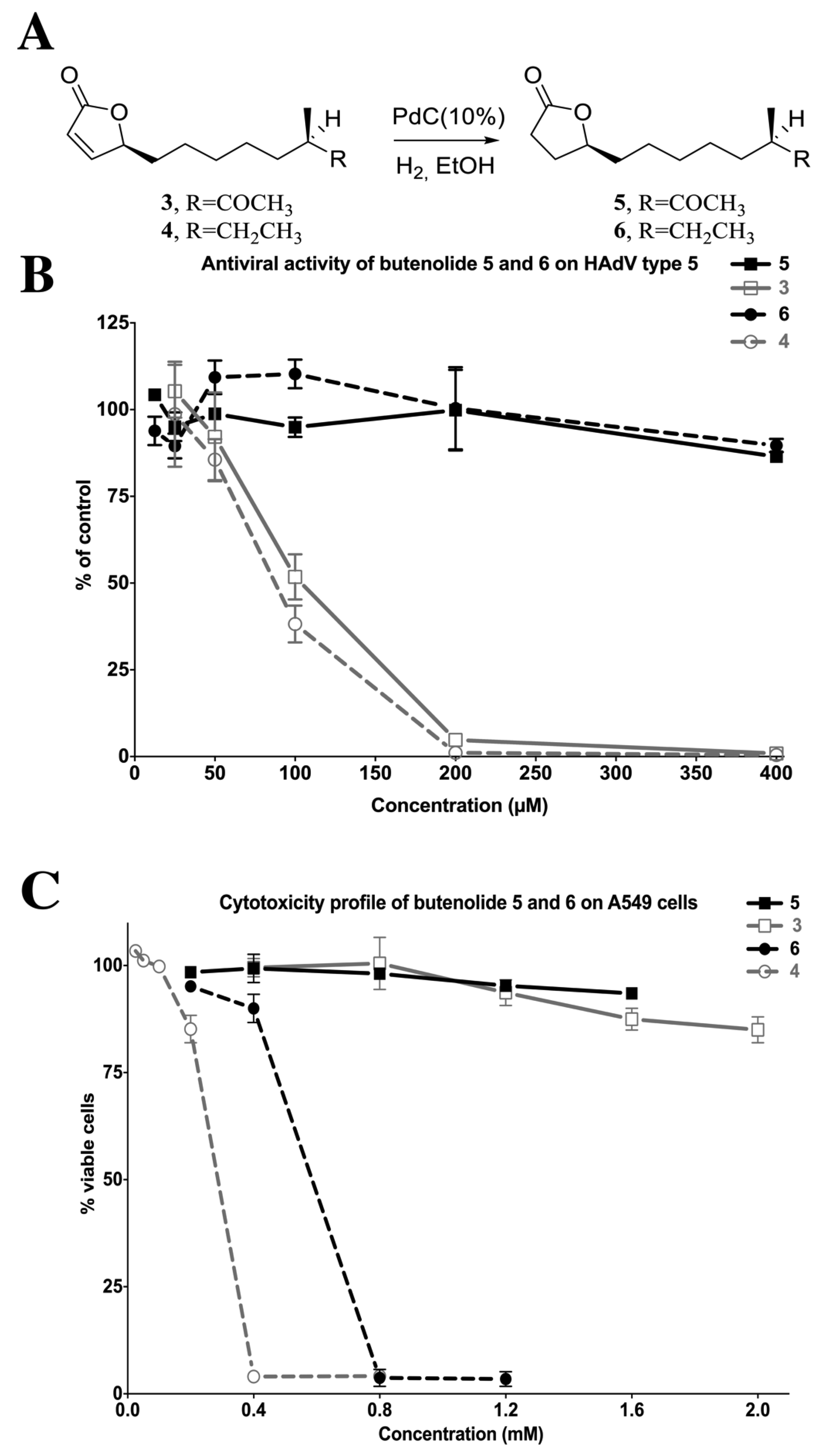

2.4. Biological Evaluation of Butenolide Analogs

3. Experimental Section

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

3.2. Isolation of Actinobacteria from the Arctic Sea

3.3. Extract Library

3.4. Streptomyces sp.

3.5. Fermentation

3.6. Bioactivity Guided Fractionation

3.7. Extraction and Isolation of Secondary Metabolites from Marine Actinobacteria

3.8. Cells and Virus

3.11. Cytotoxicity Assessment

3.12. Binding Assay

3.13. Virucidal Assay

3.14. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Files

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kwon, H.C.; Kauffman, C.A.; Jensen, P.R.; Fenical, W. Marinomycins a–d, antitumor-antibiotics of a new structure class from a marine actinomycete of the recently discovered genus “marinispora”. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 1622–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotchev, S.B. Marine actinomycetes as an emerging resource for the drug development pipelines. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 158, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudhomme, J.; McDaniel, E.; Ponts, N.; Bertani, S.; Fenical, W.; Jensen, P.; Le Roch, K. Marine actinomycetes: A new source of compounds against the human malaria parasite. PLoS One 2008, 3, e2335. [Google Scholar]

- Dionisi, H.M.; Lozada, M.; Olivera, N.L. Bioprospection of marine microorganisms: Potential and challenges for argentina. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2012, 44, 122–132. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, A.M.; Rodriguez, A.D.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O.; Fusetani, N. Marine pharmacology in 2009–2011: Marine compounds with antibacterial, antidiabetic, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antiprotozoal, antituberculosis, and antiviral activities; affecting the immune and nervous systems, and other miscellaneous mechanisms of action. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 2510–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, B.N.; Knipe, D.M.; Howley, P.M. Fields Virology, 5th ed.; Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hierholzer, J.C. Adenoviruses in the immunocompromised host. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1992, 5, 262–274. [Google Scholar]

- Van Tol, M.J.; Kroes, A.C.; Schinkel, J.; Dinkelaar, W.; Claas, E.C.; Jol-van der Zijde, C.M.; Vossen, J.M. Adenovirus infection in paediatric stem cell transplant recipients: Increased risk in young children with a delayed immune recovery. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005, 36, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, L.; Papareddy, P.; Silver, J.; Bergh, A.; Mei, Y.F. Replication-competent ad11p vector (rcad11p) efficiently transduces and replicates in hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer cells. Hum. Gene Ther. 2009, 20, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E.K.; Strand, M.; Edlund, K.; Lindman, K.; Enquist, P.A.; Spjut, S.; Allard, A.; Elofsson, M.; Mei, Y.F.; Wadell, G. Small-molecule screening using a whole-cell viral replication reporter gene assay identifies 2-[2-(benzoylamino)benzoylamino]benzoic acid as a novel antiadenoviral compound. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 3871–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberg, C.T.; Strand, M.; Andersson, E.K.; Edlund, K.; Tran, N.P.; Mei, Y.F.; Wadell, G.; Elofsson, M. Synthesis, biological evaluation, and structure-activity relationships of 2-[2-(benzoylamino)benzoylamino]benzoic acid analogues as inhibitors of adenovirus replication. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 3170–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, M.; Islam, K.; Edlund, K.; Oberg, C.T.; Allard, A.; Bergstrom, T.; Mei, Y.F.; Elofsson, M.; Wadell, G. 2-[4,5-difluoro-2-(2-fluorobenzoylamino)-benzoylamino]benzoic acid, an antiviral compound with activity against acyclovir-resistant isolates of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 5735–5743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.H.; Zhu, T.J.; Liu, H.B.; Fang, Y.C.; Gu, Q.Q.; Zhu, W.M. Four butenolides are novel cytotoxic compounds isolated from the marine-derived bacterium, streptoverticillium luteoverticillatum 11014. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2006, 29, 624–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; He, H.; Schulz, S.; Liu, X.; Fusetani, N.; Xiong, H.; Xiao, X.; Qian, P.Y. Potent antifouling compounds produced by marine streptomyces. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 1331–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukku, V.J.; Speitling, M.; Laatsch, H.; Helmke, E. New butenolides from two marine streptomycetes. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 1570–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickschat, J.S.; Martens, T.; Brinkhoff, T.; Simon, M.; Schulz, S. Volatiles released by a streptomyces species isolated from the north sea. Chem. Biodivers. 2005, 2, 837–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, S.; Andersson, F.; Breistein, P.; Hedenström, E. Synthesis of butenolides recently isolated from marine microorganisms. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 7878–7881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.-M.; Shi, L.; Li, Y. Total synthesis of (4s,10r)-4-hydroxy-10-methyl-11-oxododec-2-en-1,4-olide and related bioactive marine butenolides. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2008, 19, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dai, W.-M. Total synthesis of diastereomeric marine butenolides possessing a syn-aldol subunit at c10 and c11 and the related c11-ketone. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Xiao, K.; Chandramouli, K.H.; Xu, Y.; Pan, K.; Wang, W.X.; Qian, P.Y. Acute toxicity of the antifouling compound butenolide in non-target organisms. PLoS One 2011, 6, e23803. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Zhang, H.; He, L.; Liu, C.; Xu, Y.; Qian, P.Y. Butenolide inhibits marine fouling by altering the primary metabolism of three target organisms. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012, 7, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.M.; Peng, S.Q.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, M.W.; Yan, C.H.; Yang, H.Y.; Wang, G.Q. Depletion of intracellular glutathione mediates butenolide-induced cytotoxicity in hepg2 cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2006, 164, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon-Montano, J.M.; Burgos-Moron, E.; Orta, M.L.; Pastor, N.; Austin, C.A.; Mateos, S.; Lopez-Lazaro, M. Alpha, beta-unsaturated lactones 2-furanone and 2-pyrone induce cellular DNA damage, formation of topoisomerase i- and ii-DNA complexes and cancer cell death. Toxicol. Lett. 2013, 222, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredholt, H.; Fjaervik, E.; Johnsen, G.; Zotchev, S.B. Actinomycetes from sediments in the trondheim fjord, norway: Diversity and biological activity. Mar. Drugs 2008, 6, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mybiosoftware. Available online: http://www.mybiosoftware.com/file-conversion/1435 (accessed on 21 January 2014).

- DNA Baser Sequence Assembler. Available online: http://www.dnabaser.com (accessed on 21 January 2014).

- Decipher’s Web Tool. Available online: http://decipher.cee.wisc.edu/FindChimeras.html (accessed on 21 January 2014).

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar]

- Riedlinger, J.; Reicke, A.; Zahner, H.; Krismer, B.; Bull, A.T.; Maldonado, L.A.; Ward, A.C.; Goodfellow, M.; Bister, B.; Bischoff, D.; et al. Abyssomicins, inhibitors of the para-aminobenzoic acid pathway produced by the marine verrucosispora strain ab-18-032. J. Antibiot. 2004, 57, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, A.; Albinsson, B.; Wadell, G. Rapid typing of human adenoviruses by a general pcr combined with restriction endonuclease analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heid, C.A.; Stevens, J.; Livak, K.J.; Williams, P.M. Real time quantitative pcr. Genome Res. 1996, 6, 986–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehm, N.W.; Rodgers, G.H.; Hatfield, S.M.; Glasebrook, A.L. An improved colorimetric assay for cell proliferation and viability utilizing the tetrazolium salt XTT. J. Immunol. Methods 1991, 142, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segerman, A.; Arnberg, N.; Erikson, A.; Lindman, K.; Wadell, G. There are two different species b adenovirus receptors: Sbar, common to species b1 and b2 adenoviruses, and sb2ar, exclusively used by species b2 adenoviruses. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 1157–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Strand, M.; Carlsson, M.; Uvell, H.; Islam, K.; Edlund, K.; Cullman, I.; Altermark, B.; Mei, Y.-F.; Elofsson, M.; Willassen, N.-P.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of Anti-Adenoviral Secondary Metabolites from Marine Actinobacteria. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 799-821. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12020799

Strand M, Carlsson M, Uvell H, Islam K, Edlund K, Cullman I, Altermark B, Mei Y-F, Elofsson M, Willassen N-P, et al. Isolation and Characterization of Anti-Adenoviral Secondary Metabolites from Marine Actinobacteria. Marine Drugs. 2014; 12(2):799-821. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12020799

Chicago/Turabian StyleStrand, Mårten, Marcus Carlsson, Hanna Uvell, Koushikul Islam, Karin Edlund, Inger Cullman, Björn Altermark, Ya-Fang Mei, Mikael Elofsson, Nils-Peder Willassen, and et al. 2014. "Isolation and Characterization of Anti-Adenoviral Secondary Metabolites from Marine Actinobacteria" Marine Drugs 12, no. 2: 799-821. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12020799

APA StyleStrand, M., Carlsson, M., Uvell, H., Islam, K., Edlund, K., Cullman, I., Altermark, B., Mei, Y.-F., Elofsson, M., Willassen, N.-P., Wadell, G., & Almqvist, F. (2014). Isolation and Characterization of Anti-Adenoviral Secondary Metabolites from Marine Actinobacteria. Marine Drugs, 12(2), 799-821. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12020799