SxtA and sxtG Gene Expression and Toxin Production in the Mediterranean Alexandrium minutum (Dinophyceae)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

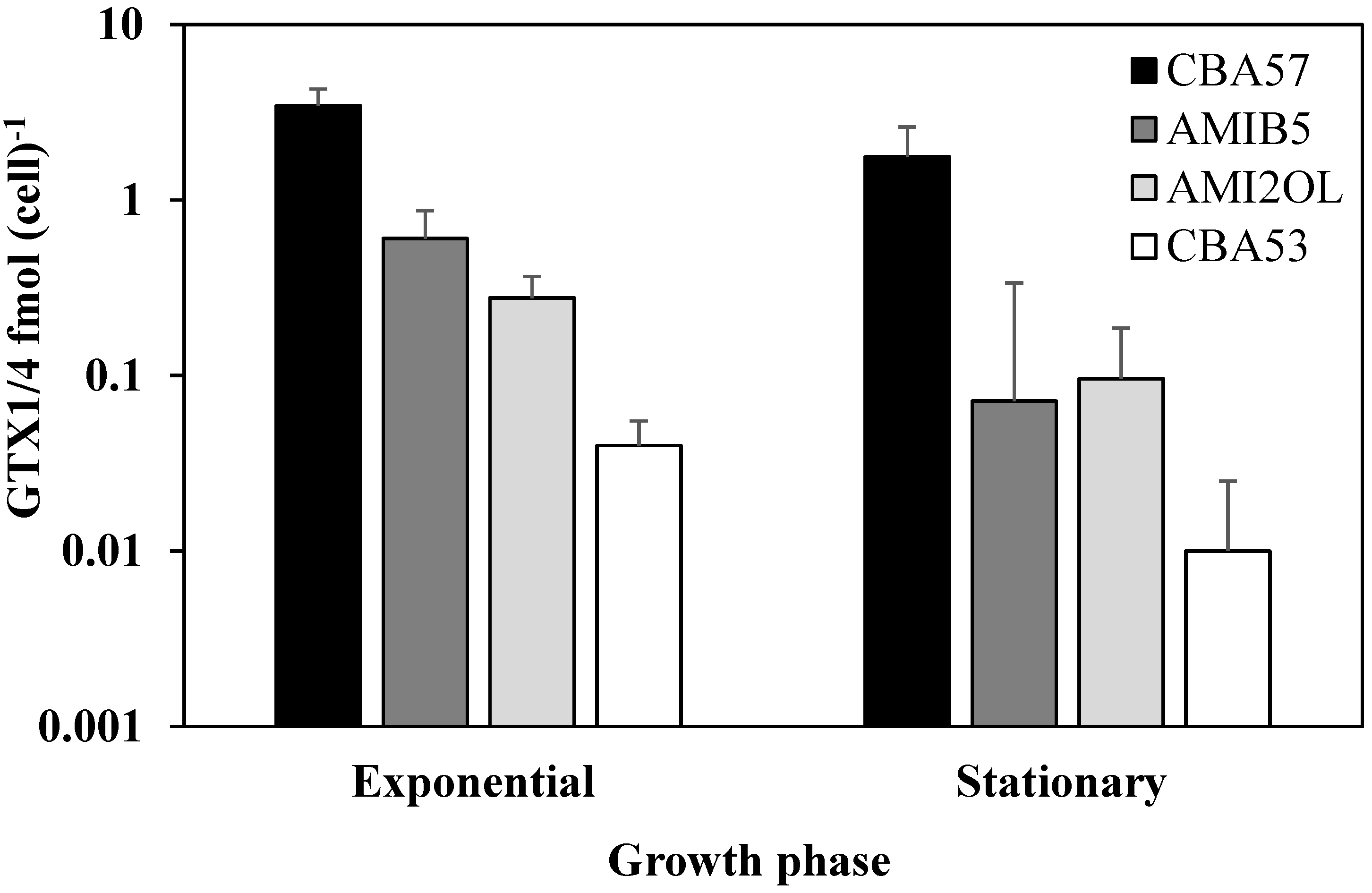

2.1. Toxin Content in Standard Condition

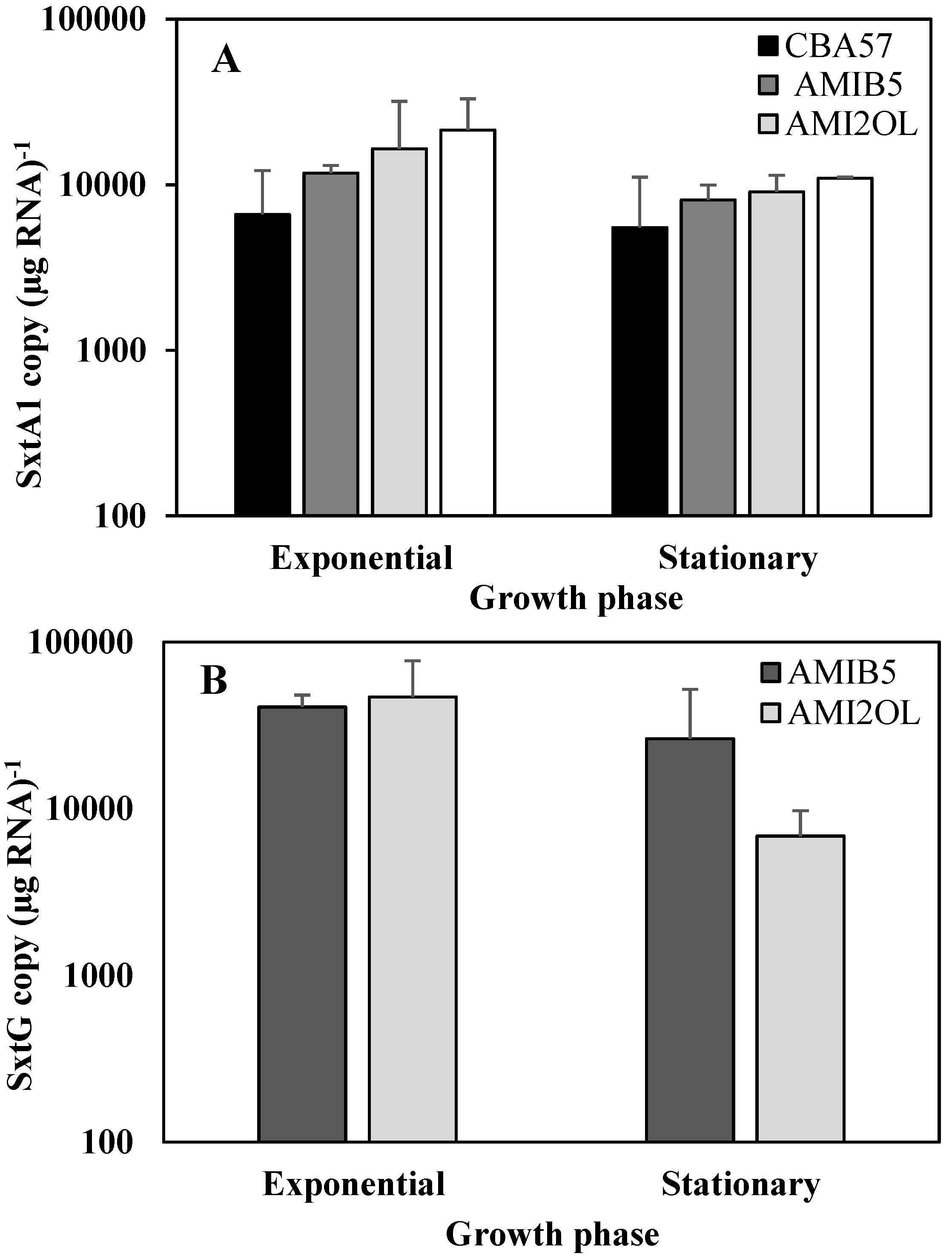

2.2. The sxtA1 and sxtG Gene Expression in Standard Condition

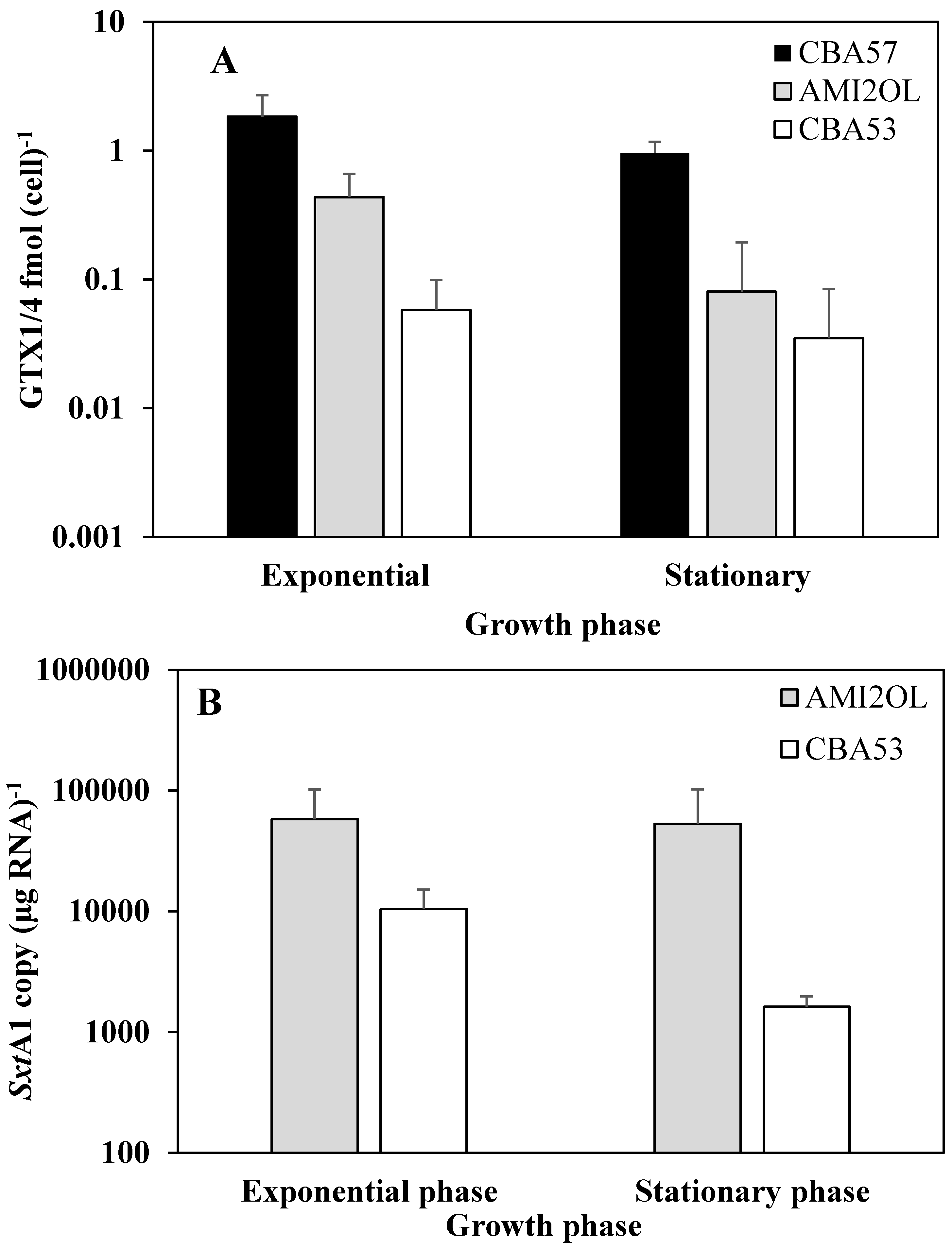

2.3. The sxtA1 Gene Expression and Toxin Content under Phosphorus Limitation

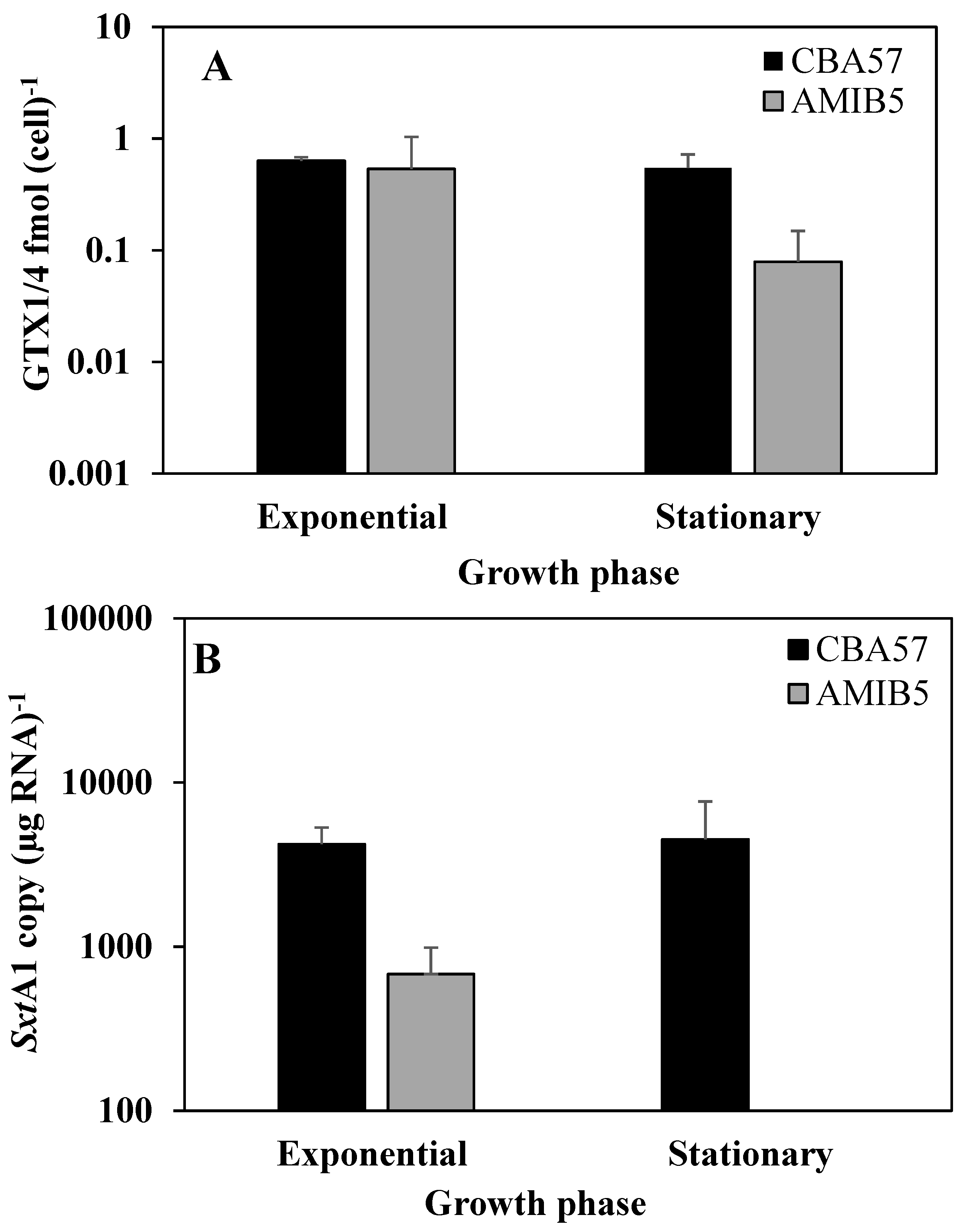

2.4. The sxtA1 Gene Expression and Toxin Content under Nitrogen Limitation

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Strain Cultures

3.2. Toxin Analysis

3.2.1. Chemicals

3.2.2. Pellet Extraction

3.2.3. LC-HRMS

| Toxin | Precursor Ion (m/z) | Formula | Product Ion (m/z) | Collision Energy (CE) % | LOD (ng/mL) | LOQ (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTX1/4 | 332.1 | [M + H − SO3]+ | 314.1204 253.1041 | 20 | 5/30 | 11/56 |

| STX | 300.1 | [M + H]+ | 282.1311 221.1143 204.0877 | 22 | 21 | 40 |

| B1 | 300.1 | [M + H − SO3]+ | 282.1311 221.1143 204.0877 | 22 | 43 | 86 |

| dcSTX | 257.1 | [M + H]+ | 239.1255 222.0984 180.0765 | 24 | 37 | 70 |

| GTX2/3 | 316.1 | [M + H − SO3]+ | 298.1254 220.0824 | 21 | 40/30 | 78/60 |

| C1/2 | 316.1 | [M + H − 2SO3]+ | 298.1254 | 21 | 23/28 | 47/60 |

| NEO | 316.1 | [M + H]+ | 298.1254 220.0824 | 21 | 9 | 18 |

| dcGTX2/3 | 273.1 | [M + H − SO3]+ | 255.1201 238.0933 | 25 | 71/60 | 140/130 |

| dcNEO | 273.1 | [M + H]+ | 255.1201 | 25 | 70 | 140 |

3.2.4. Matrix Effect

3.3. RNA Extraction and Reverse-Transcription

3.4. Primer Design and qPCR Conditions

| Primers | Sequences 5′→3′ | Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| sxtA1 alex. F sxtA1 alex. R | GCAGCGATGCTACTCCTACTACGT Tcgaagakgatgckgtggtacct | 600 nM 600 nM |

| sxtG F sxtG R | Ccgggccgtgaaggat tgtggctcgtcgatttcga | 600 nM 600 nM |

| Act a.min upp. Act a.min low. | Agattgtgcgcgatgtcaagg cgccgtgatgatgattccctc | 400 nM 400 nM |

| 5.8S 3′ 5.8S 5′ | [53] | 400 nM 400 nM |

| β2M F β2M R | [54] | 200 nM 200 nM |

3.5. Nutrient Analyses

3.6. Statistical Analyses

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Files

Supplementary File 1Acknowledgments

Author contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Taylor, F.J.R. General group characteristics, special features of interest, short history of dinoflagellate study. In The Biology of Dinoflagellates. Botanical Monographs; Taylor, F.J.R., Ed.; Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford, UK, 1987; Volume 21, p. 798. [Google Scholar]

- Wisecaver, J.H.; Hackett, J.D. Dinoflagellate genome evolution. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 65, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davy, S.K.; Allemand, D.; Weis, V.M. Cell biology of cnidarian-dinoflagellate symbiosis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012, 76, 229–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallegraeff, G.M. A review of harmful algal blooms and their apparent global increase. Phycologia 1993, 32, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daranas, A.H.; Norte, M.; Fernández, J.J. Toxic marine microalgae. Toxicon 2001, 39, 1101–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallegraeff, G.M. Harmful algal blooms: A global overview. In Manual on Harmful Marine Microalgae; Hallegraeff, G.M., Anderson, D.M., Cembella, A.D., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1995; Volume 33, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.Z. Neurotoxins from marine dinoflagellates: A brief review. Mar. Drugs 2008, 6, 349–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rein, K.S.; Borrone, J. Polyketides from dinoflagellates: Origins, pharmacology and biosynthesis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1999, 124, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satake, M.; Murata, M.; Yasumoto, T.; Fujita, T.; Naoki, H. Amphidinol, a polyhydroxypolyene antifungal agent with an unprecedented structure, from a marine dinoflagellate, Amphidinium klebsii. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 9859–9861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeds, J.R.; Landsberg, J.H.; Etheridge, S.M.; Pitcher, G.C.; Longan, S.W. Non-Traditional vectors for paralytic shellfish poisoning. Mar. Drugs 2008, 6, 308–348. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wiese, M.; D’Agostino, P.M.; Mihali, T.K.; Moffitt, M.C.; Neilan, B.A. Neurotoxic alkaloids: Saxitoxin and its analogs. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 2185–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.L.; Boyer, G.L.; Zimba, P.V. A review of cyanobacterial odorous and bioactive metabolites: Impacts and management alternatives in aquaculture. Aquaculture 2008, 280, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, R.J.S.; Stüken, A.; Rundberget, T.; Eikrem, W.; Jakobsen, K.S. Improved phylogenetic resolution of toxic and non-toxic Alexandrium strains using a concatenated rDNA approach. Harmful Algae 2011, 10, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.M.; Alpermann, T.J.; Cembella, A.D.; Collos, Y.; Masseret, E.; Montresor, M. The globally distributed genus Alexandrium: Multifaceted roles in marine ecosystems and impacts on human health. Harmful Algae 2012, 14, 10–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penna, A.; Fraga, S.; Masó, M.; Giacobbe, M.G.; Bravo, I.; Garcés, E.; Vila, M.; Bertozzini, E.; Andreoni, F.; Luglié, A.; et al. Phylogenetic relationships among the Mediterranean Alexandrium (Dinophyceae) species based on sequences of 5.8S gene and Internal Transcript Spacers of the rRNA operon. Eur. J. Phycol. 2008, 43, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzet, N.; Franco, J.M.; Raine, R. Morphogenetic diversity and biotoxin composition of Alexandrium (Dinophyceae) in Irish coastal waters. Harmful Algae 2008, 7, 782–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, P.-T.; Sato, S.; van Thuoc, C.; The Tu, P.; Thi Minh Huyen, N.; Takata, Y.; Yoshida, M.; Kobiyama, A.; Koike, K.; Ogata, T. Toxic Alexandrium minutum (Dinophyceae) from Vietnam with new gonyautoxin analogue. Harmful Algae 2007, 6, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Aversano, C.; Walter, J.A.; Burton, I.W.; Stirling, D.J.; Fattorusso, E.; Quilliam, M.A. Isolation and structure elucidation of new and unusual saxitoxin analogues from mussels. J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 71, 1518–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellmann, R.; Mihali, T.K.; Jeon, Y.J.; Pickford, R.; Pomati, F.; Neilan, B.A. Biosynthetic intermediate analysis and functional homology reveal a saxitoxin gene cluster in cyanobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 4044–4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihali, T.K.; Kellmann, R.; Neilan, B.A. Characterisation of the paralytic shellfish toxin biosynthesis gene clusters in Anabaena circinalis AWQC131C and Aphanizomenon sp. NH-5. BMC Biochem. 2009, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustafa, A.; Loram, J.E.; Hackett, J.D.; Anderson, D.M.; Plumley, F.G.; Bhattacharya, D. Origin of saxitoxin biosynthetic genes in cyanobacteria. PLoS One 2009, 4, e5758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stucken, K.; John, U.; Cembella, A.; Murillo, A.A.; Soto-Liebe, K.; Fuentes-Valdés, J.J.; Friedel, M.; Plominsky, A.M.; Vásquez, M.; Glöckner, G. The smallest known genomes of multicellular and toxic cyanobacteria: Comparison, minimal gene sets for linked traits and the evolutionary implications. PLoS One 2010, 5, e9235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihali, T.K.; Carmichael, W.W.; Neilan, B.A. A putative gene cluster from a Lyngbya wollei bloom that encodes paralytic shellfish toxin biosynthesis. PLoS One 2011, 6, e14657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, F.M.J.; Wood, S.A.; van Ginkel, T.; Broady, P.A.; Gaw, S. First report of saxitoxin production by a species of the freshwater benthic cyanobacterium, Scyttonema Agardh. Toxicon 2011, 57, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Norte, M.; Shimizu, Y. Biosynthesis of saxitoxin analogues: The origin and introduction mechanism of the side-chain carbon. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1989, 19, 1421–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, Y. Microalgal metabolites. Chem. Rev. 1993, 93, 1685–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellmann, R.; Stüken, A.; Orr, R.J.S.; Svendsen, H.M.; Jakobsen, K.S. Biosynthesis and molecular genetics of polyketides in marine dinoflagellates. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 1011–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, I.; John, U.; Beszteri, S.; Glöckner, G.; Krock, B.; Goesmann, A.; Cembella, A.D. Comparative gene expression in toxic versus non-toxic strains of the marine dinoflagellate Alexandrium minutum. BMC Genomics 2010, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stüken, A.; Orr, R.J.S.; Kellmann, R.; Murray, S.A.; Neilan, B.A.; Kjetill, S.J. Discovery of nuclear-encoded genes for the neurotoxin saxitoxin in dinoflagellates. PLoS One 2011, e0020096. [Google Scholar]

- Kellmann, R.; Neilan, B.A. Biochemical characterization of paralytic shellfish toxin biosynthesis in vitro. J. Phycol. 2007, 43, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, R.J.S.; Stüken, A.; Murray, S.A.; Jakobsen, S.K. Evolutionary acquisition and loss of saxitoxin biosynthesis in dinoflagellates: The Second “Core” Gene, sxtG. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 2128–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guisande, C.; Frangópulos, M.; Maneiro, I.; Vergara, A.R.; Riveiro, I. Ecological advantages of toxin production by the dinoflagellate Alexandrium minutum under phosphorus limitation. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2002, 225, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippemeier, S.; Frampton, D.M.F.; Blackburn, S.I.; Geier, S.C.; Negri, A.P. Influence of phosphorus limitatio on toxicity and photosynthesis of Alexandrium minutum (dinophyceae) monitored by in-line detection of variable chlorophyll fluorescence. J. Phycol. 2003, 38, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangópulos, M.; Guisande, C.; de Blas, E.; Maneiro, I. Toxin production and competitive abilities under phosphorus limitation of Alexandrium species. Harmful Algae 2004, 3, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzet, N.; Franco, J.M.; Raine, R. Influence of inorganic nutrition on growth and PSP toxin production of Alexandrium minutum (Dinophyceae) from Cork Harbour, Ireland. Toxicon 2007, 50, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Aversano, C.; Hess, P.; Quilliam, M.A. Hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry for the analysis of paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) toxins. J. Chromatogr. A 2005, 1081, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cembella, A.D.; Sullivan, J.J.; Boyer, G.L.; Taylor, F.J.R.; Andersen, R.J. Variation in paralytic shellfish toxin composition within the Protogonyaulax tamarensis/catenella species complex; red tide dinoflagellates. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 1987, 15, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.M.; Kulis, D.M.; Sullivan, J.J.; Hall, S.; Lee, C. Dynamics and physiology of saxitoxin production by the dinoflagellates Alexandrium spp. Mar. Biol. 1990, 104, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cembella, A.D. Ecophysiology and metabolism of paralytic shellfish toxins in marine microalgae. In Physiological Ecology of Harmful Algal Blooms; Anderson, D.M., Cembella, A.D., Hallegraeff, G.M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1998; pp. 381–403. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, I.; Beszteri, S.; Tillmann, U.; Cembella, A.; John, U. Growth- and nutrient-dependent gene expression in the toxigenic marine dinoflagellate. Alexandrium minutum. Harmul. Algae 2011, 12, 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- Béchemin, C.; Grzebyk, D.; Hachame, F.; Hummert, C.; Maesrini, S.Y. Effect of different nitrogen/phosphorus nutrient ratios on the toxin content in Alexandrium minutum. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 1999, 20, 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, S.A.; Mihali, T.K.; Neilan, B.A. Extraordinary conservation, gene loss, and positive selection in the evolution of an ancient neurotoxin. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011, 28, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, Y. Microalgal metabolites: A new perspective. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1996, 50, 431–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackett, J.D.; Wisecaver, J.H.; Brosnahan, M.L.; Kulis, D.M.; Anderson, D.M.; Bhattacharya, D.; Plumley, F.G.; Erdner, D.L. Evolution of saxitoxin synthesis in cyanobacteria and dinoflagellates. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salcedo, T.; Upadhyay, R.J.; Nagasaki, K.; Bhattacharya, D. Dozens of toxin-related genes are expressed in a nontoxic strain of the dinoflagellate Heterocapsa circularisquama. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2012, 29, 1503–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestrini, S.Y.; Bechemin, C.; Grzebyk, D.; Hummert, C. Phosphorus limitation might promote more toxin content in the marine invader dinoflagellate Alexandrium minutum. Plank. Biol. Ecol. 2000, 47, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Selander, E.; Cervin, G.; Pavia, H. Effect of nitrate and phosphate on grazer-induced toxin production in Alexandrium minutum. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2008, 53, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casabianca, S.; Penna, A.; Pecchioli, E.; Jordi, A.; Basterretxea, G.; Vernesi, C. Population genetic structure and connectivity of the harmful dinoflagellate Alexandrium minutum in the Mediterranean Sea. Proc. R. Soc. B 2012, 279, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penna, N.; Capellacci, S.; Ricci, F. The influence of the Po River discharge on phytoplankton bloom dynamics along the coastline of Pesaro (Italy) in the Adriatic Sea. Mar. Poll. Bull. 2004, 48, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, M.; Giacobbe, M.G.; Masó, M.; Gangemi, E.; Penna, A.; Sampedro, N.; Azzaro, F.; Camp, J.; Galluzzi, L. A comparative study on recurrent blooms of Alexandrium minutum in two Mediterranean coastal areas. Harmful Algae 2005, 4, 673–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillard, R.R.L. Culture of phytoplankton for feeding marine invertebrates. In Culture of Marine Invertebrate Animals; Smith, W.L., Chanley, M.H., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 29–60. [Google Scholar]

- Utermöhl, H. Zur Vervollkommnung der quantitativen Phytoplankton-Methodik. Mitt. Int. Ver. Theor. Angew. Limnol. 1958, 9, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi, L.; Penna, A.; Bertozzini, E.; Giacobbe, M.G.; Vila, M.; Garcés, E.; Prioli, S.; Magnani, M. Development of a qualitative PCR method for the Alexandrium spp. (Dinophyceae) detection in contaminated mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis). Harmful Algae 2005, 4, 973–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandi, G.; Fraternale, A.; Lucarini, S.; Paiardini, M.; de Santi, M.; Cervasi, B.; Paoletti, M.F.; Galluzzi, L.; Duranti, A.; Magnani, M. Antitumoral activity of indole-3-carbinol cyclic tri- and tetrameric derivatives mixture in human breast cancer cells: In vitro and in vivo studies. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, J.D.H.; Parsons, T.R. A Practical Handbook of Seawater Analysis, 2nd ed.; Fisheries Research Board on Canada: Ottawa, Canada, 1972; p. 311. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, Ø; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeon. Electr. 2001, 4, 9. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perini, F.; Galluzzi, L.; Dell'Aversano, C.; Iacovo, E.D.; Tartaglione, L.; Ricci, F.; Forino, M.; Ciminiello, P.; Penna, A. SxtA and sxtG Gene Expression and Toxin Production in the Mediterranean Alexandrium minutum (Dinophyceae). Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 5258-5276. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12105258

Perini F, Galluzzi L, Dell'Aversano C, Iacovo ED, Tartaglione L, Ricci F, Forino M, Ciminiello P, Penna A. SxtA and sxtG Gene Expression and Toxin Production in the Mediterranean Alexandrium minutum (Dinophyceae). Marine Drugs. 2014; 12(10):5258-5276. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12105258

Chicago/Turabian StylePerini, Federico, Luca Galluzzi, Carmela Dell'Aversano, Emma Dello Iacovo, Luciana Tartaglione, Fabio Ricci, Martino Forino, Patrizia Ciminiello, and Antonella Penna. 2014. "SxtA and sxtG Gene Expression and Toxin Production in the Mediterranean Alexandrium minutum (Dinophyceae)" Marine Drugs 12, no. 10: 5258-5276. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12105258

APA StylePerini, F., Galluzzi, L., Dell'Aversano, C., Iacovo, E. D., Tartaglione, L., Ricci, F., Forino, M., Ciminiello, P., & Penna, A. (2014). SxtA and sxtG Gene Expression and Toxin Production in the Mediterranean Alexandrium minutum (Dinophyceae). Marine Drugs, 12(10), 5258-5276. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12105258