Jellyfish Stings and Their Management: A Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

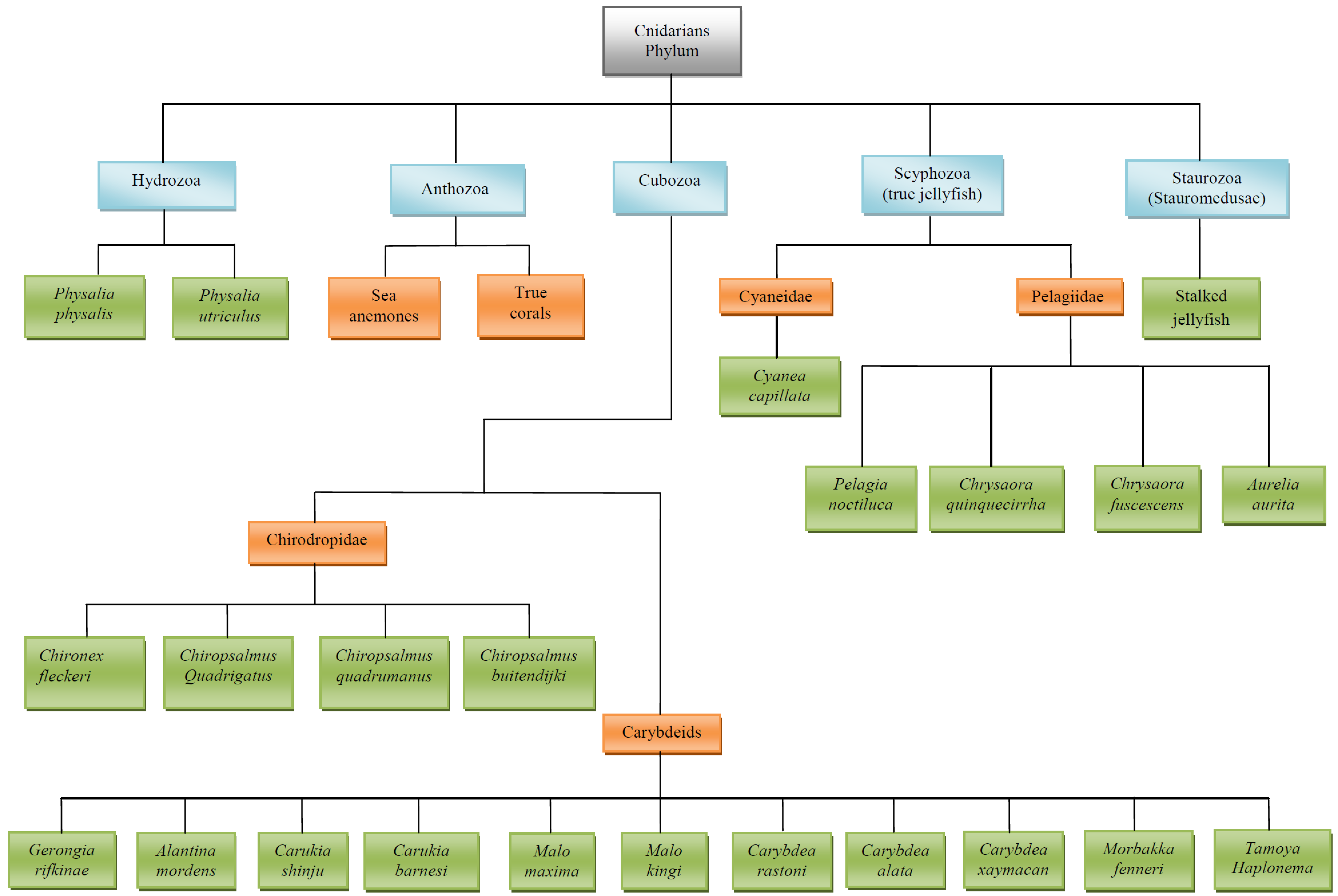

3. Main Stinging Pelagic Cnidaria (Figure 1 Illustrates the Taxonomy of Cnidarians)

3.1. Physalia Species

- (1)

- Physalia physalis (the Portuguese Man O’ War): This worldwide species has a boat-like pneumatophore 2–25 cm long, with multi-tentacles measuring from 10 m up to 30 m [1]; yet, it is not a true jellyfish. This species is responsible for a large number of stings, with some being fatal.

- (2)

3.2. Cubozoans Species

3.2.1. Chironex fleckeri

3.2.2. Chiropsalmus quadrigatus

3.2.3. Chiropsalmus quadrumanus

3.2.4. Carukia barnesi and Other Australian Carybdeids

3.2.5. Carybdea rastoni

3.2.6. Carybdea alata

3.2.7. Morbakka

3.3. Pelagiidae Species

3.3.1. Pelagia noctiluca

3.3.2. Chrysaora quinquecirrha

3.4. Cyaneidae Species

Cyanea capillata

3.5. Pelagic Cnidaria: Distribution, Envenomation and Treatment

| Species and Size | Geographic Distribution | Local Symptoms | Systemic Symptoms; (Deadly = D) |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. physalis Float: 2–30 cm high Tentacles: 10–30 m | worldwide, more common in tropical waters [1,2,7,16] | acute pain, wheals ≥7 cm, skin necrosis after 24 h (++/+++) [1,2,16] | muscular spasms, abdominal pain, arrhythmias, headache, D [1,2,16] |

| P. utriculus Float: 2–10 cm high Single tentacle: 2–5 m | Tropical Indo-Pacific ocean, Australia, South-Atlantic [1,2] | local pain, wheals (+/++) [1,2] | very rare or none [1,2] |

| C. fleckeri Bell: (20 × 30) cm Tentacles: 2–3 m | Indo-Pacific region and Australia [1,2] | pain, massive wheals, vesicles for 10 days, scarring (+++) [1,2,31] | severe hypotension, cardiac failure/arrest, arrhythmias, pulmonary hypertension, D [1,31] |

| C. quadrigatus Bell: (10 × 8) cm Tentacles: 5–30 cm | Australia, Indo-Pacific region [1,2] | pain, wheals, swelling for 24 h (++/+++) | asystole, bradycardia, hypotension, pulmonary hypertension/oedema, D [1,59,75] |

| C. quadrumanus Bell: (14 × 10) cm Tentacles: 3–4 m | North West Atlantic, Caribbean and Brazil [6,82] | pain, wheals (for 24 h); scarring and dyschromia for 2 months (++/+++) [2,82] | hypotension, acute cardiac failure, pulmonary hypertension/oedema, D [2,82] |

| C. barnesi Bell: (2.5 × 2) cm Tentacles: 5–35 cm | Australia [1,2] | oval erythema 5 × 7 cm with surrounding papules (+/++) [1,2,83] | Irukandji syndrome (back pain, severe hypertension, agitation, muscle cramps, headache, nausea/vomiting, sweating), D [1,2,83] |

| Morbakka Bell: (11 × 5) cm Tentacles: 10 cm | Australia [1,2] | 10 mm wide wheals, intense pain, itching, vesicles, skin necrosis (++/+++) [1,2,83] | Irukandji syndrome (muscle spasms, back pain, anxiety, respiratory distress, hypotension, sweating) [1,2,83] |

| C. rastoni Bell: (5 × 2) cm Tentacles: 5–30 cm | Australia [1,2] | delayed and moderate pain, wheals (3–12 mm width), swelling, blisters (rare), pigmentary changes for 2 weeks after sting (++) [1] | No [1] |

| C. alata Bell: (9 × 5) cm Tentacles: 30–40 cm | tropical and sub-tropical Pacific waters, Hawaii [2,75,87] | pain, wheals, blisters, dyschromia for 2 weeks (++/+++) [2,51,75,87] | mild Irukandji syndrome, possible allergic reactions [52,83,87] |

| Tamoya haplonema Bell: (10 × 5) cm Tentacles: 3 cm | Atlantic ocean (tropical/sub-tropical waters) [2,7,75] | burning pain (for about 2 h), wheals, blisters/scarring (++) [2,7,75] | muscle cramps, nausea, vomiting, restless, sweating, headache [2,7,75] |

| P. noctiluca Bell: (10 × 3) cm Tentacles: 10 m | worldwide, tropical and cold waters (common in Mediterranean, North Atlantic, North Pacific) [1,2] | instant severe pain, wheals, possible hyperpigmentation (++/+++) [1,2,106] | (rare) allergic reaction and respiratory distress [1,2,105] |

| C. quinquecirrha Bell Φ: 6 cm Tentacles: 50 cm | Australia, Atlantic, Pacific, Indian ocean [1,2] | intense pain, wheals/rash for days (+/++) [1,51] | (rare) allergic reaction and respiratory distress, D [1,51] |

| C. capillata Bell Φ: ≥1 m Tentacles: 30–50 cm | worldwide; more common in North Sea, North Atlantic, Arctic Sea, North Pacific [1,2,17] | Pain, wheals, erythema may persist for days (++/+++) [1,2,17] | (possible) muscle cramps, sweating, nausea, allergic reaction [1,2,17] |

| Chirodropids | Carybdeids | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. fleckeri | C. quadrumanus | C. alata | C. barnesi | C. rastoni | Morbakka | |

| Sea water rinsing | A,B(4) [1,2] | B(4) [51], F(2) [51] | A,B(1,4) [1,2,103,104] | A(4) [1,2] | A(4) [1,2] | |

| Hot water/packs | A,B(4) [26], E(4) [70,71], F(4) [70] | A(1,3) [23,52,83,87,103] | A(4) [83] | |||

| Tentacle removal | B(4) [1,2] | B(4) [1,2] | B(4) [1,2,87] | B(4) [1,2] | B(4) [1,2] | |

| Topical Vinegar | A,B(1,4) [1,51,69] | A,B(4) [7], C(4) [51] | C(4) [87], F(4) [103] | B(4) [2] | B(4) [99] | B(4) [105] |

| Ice packs | A(1) [64] | D(2) [51] | C(4) [87], F(4) [103] | |||

| Fresh water | C(4) [11,12] | F(2) [51] | A(1) [104], C(4) [12] | |||

| BaCl2 | ||||||

| MgCl2 | ||||||

| NaOH | B(4) [105] | |||||

| NaCl | ||||||

| NaClO | ||||||

| Choline-Cl | ||||||

| MgCl2 solution | ||||||

| Urea | C(4) [53] | C(4) [51] | ||||

| Stingose § | A,B(1,4) [69] | A(1) [104], F(4) [103] | B(4) [99] | B(4) [105] | ||

| Acetone | ||||||

| Bromelain 10% | C(4) [51], F(2) [51] | |||||

| Papain | A(1) [104] | |||||

| Baking soda slurry † | B(4) [99] | B(4) [105] | ||||

| Methylated spirits | C(4) [53] | C(4) [99] | C(4) [105] | |||

| Ammonia | C(4) [51], D(2) [51] | |||||

| Ethanol | A,E(4) [11], C(4) [53] | C(4) [51], D(2) [51] | C(4) [99] | |||

| Topic lidocaine | A(2) [51], B(4) [51] | |||||

| Opiates i.v. | A(4) [1,31] | A(4) [1,31] | A(4) [83] | |||

| MgSO4 ♥ i.v. | E(4) [74] | A,E(4) [100] | ||||

| Reserpine i.v. | ||||||

| Phentolamine i.v. | E(4) [83] | |||||

| Glyceryl trinitrate ♣ | E(4) [88] | |||||

| Antihistamine i.v. | ||||||

| Anti-venom | A,E(1) [59,78] | E(4) [59,78] * | F(4) [59] | F(4) [59] | F(4) [59] | F(4) [59] |

| PIB | C(4) [114], E(4) [115] | C(4) [81] *, E(4) [114] | ||||

| Physalia | Scyphozoans | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. physalis | C. quinquecirrha | P. noctiluca | C. capillata | |

| Sea water rinsing | A(1) [1,2], B(4) [51] | B(4) [46,48], F(2) [51] | A(4) [109,110] | A(4) [109] |

| Hot water/packs | A(1,4) [43-45], F(4) [55] | F(4) [55] | ||

| Tentacle removal | B(4) [1,2] | B(4) [1,2,106] | B(4) [1,2,110] | B(4) [110] |

| Topical Vinegar | A(1,4) [46,47], B(4) [46,48,55], C(4) [7,49] | C(4) [46], D(4,2) [51] | C(4) [109] | C(4) [106] |

| Ice packs | A(1,4) [43-45] | F(4) [46,48] | A(4) [45] | |

| Fresh water | B(4) [49] | F(2) [51] | ||

| BaCl2 | B(4) [110] | B(4) [110] | ||

| MgCl2 | B(4) [110] | B(4) [110] | ||

| NaOH | C(4) [46] | |||

| NaCl | C(4) [110] | |||

| NaClO | C(4) [46] | C(4) [46] | ||

| Choline-Cl | C(4) [110] | |||

| MgCl2 solution | B(4) [110] | C(4) [46] | ||

| Urea | F(4) [51] | |||

| Stingose § | A(1) [47], B(4) [46] | B(4) [46] | ||

| Acetone | C(4) [46] | C(4) [46] | ||

| Bromelain 10% | A(1) [47], C(4) [51] | C(4) [46], F(2) [51] | ||

| Papain | A(1,4) [54], F(4) [55] | A(4) [46], B(4) [46] | ||

| Baking soda slurry † | B(1) [47],C(4) [46] | B(4) [46,109] | B(4) [46] | A(4) [42,110] |

| Methylated spirits | C(4) [49], D(1) [47] | B(4) [109] | A,B(4) [109] | |

| Ammonia | C(4) [46,51] | C(4) [51], D(4,2) [51] | ||

| Ethanol | C(4) [51] | C(4) [51], D(2) [51] | C(4) [109] | |

| Topic lidocaine | A,B(4) [51] | A(4,2) [51], B(4) [51] | ||

| Opiates i.v. | A(4) [31] | |||

| MgSO4 ♥ i.v. | ||||

| Reserpine i.v. | E(4) [56] | |||

| Phentolamine i.v. | ||||

| Glyceryl trinitrate ♣ | ||||

| Antihistamine i.v. | E(4) [57] | E(4) [108] | E(4) [108] | E(4) [108] |

| Anti-venom | F(4) [78] | F(4) [78] | ||

| PIB | ||||

4. Discussion

- Alleviating the local effects of venom (pain and tissue damage);

- Preventing further discharge of nematocysts;

- Controlling systemic reactions, including shock.

5. Conclusions

Conflict of Interest

References

- Tibballs, J. Australian venomous jellyfish, envenomation syndromes, toxins and therapy. Toxicon 2006, 48, 830–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, J.A.; Fenner, P.J.; Burnett, J.W.; Rifkin, J.F. Venomous & Poisonous Marine Animals: A Medical and Biological Handbook; Surf Life Saving Australia and University of New South Wales Press: Sydney, Australia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kramp, P.L. Synopsis of the medusae of the world. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 1961, 40, 1–469. [Google Scholar]

- Mariscal, R.N. Nematocysts. In Coelenterate Biology: Reviews and New Perspectives; Muscatine, L., Lenhoff, H.M., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 129–178. [Google Scholar]

- Tardent, P. The cnidarian cnidocyte, a high-tech cellular weaponry. BioEssays 1995, 17, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotan, A.; Fishman, L.; Zlotkin, E. Toxin compartmentation and delivery in the Cnidaria: The nematocyst’s tubule as a multiheaded poisonous arrow. J. Exp. Zool. 1996, 275, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, V.; Lang da Silveira, F.; Migotto, A.E. Skin lesions in envenoming by cnidarians (Portuguese man-of-war and jellyfish): Etiology and severity of accidents on the Brazilian Coast. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2012, 52, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ozacmak, V.H.; Thorington, G.U.; Fletcher, W.H.; Hessinger, D.A. N-acetylneuraminic acid (NANA) stimulates in situ cyclic AMP production in tentacles of sea anemone (Aiptasia pallida): Possible role in chemosensitization of nematocyst discharge. J. Exp. Biol. 2001, 204, 2011–2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lubbock, R.; Amos, W.B. Removal of bound calcium from nematocysts causes discharge. Nature (Lond.) 1981, 290, 500–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fautin, D.G. Structural diversity, systematics, and evolution of cnidae. Toxicon 2009, 54, 1054–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.H. Observations on jellyfish stingings in North Queensland. Med. J. Aust. 1960, 47, 993–999. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, J.H. Studies on three venomous cubomedusae. Symp. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1966, 16, 307–332. [Google Scholar]

- Grady, J.D.; Burnett, J.W. Irukandji-Like syndrome in South Florida divers. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2003, 42, 763–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippmann, J.M.; Fenner, P.J.; Winkel, K.; Gershwin, L.A. Fatal and severe box jellyfish stings, including Irukandji stings, in Malaysia, 2000–2010. J. Travel Med. 2011, 18, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestwich, H. Treatment of jellyfish stings in UK coastal waters: Vinegar or sodium bicarbonate? Emerg. Med. J. 2007, 24, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labadie, M.; Aldabe, B.; Ong, N.; Joncquiert-latarjet, A.; Groult, V.; Poulard, A.; Coudreuse, M.; Cordier, L.; Rolland, P.; Chanseau, P.; De Haro, L. Portuguese man-of-war (Physalia physalis) envenomation on the Aquitaine Coast of France: An emerging health risk. Clin. Toxicol. (Phila.) 2012, 50, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tønseth, A. Health damage after jellyfish stings. Tidsskr. Nor. Lægeforen. (Norwegian) 2007, 127, 1777–1778. [Google Scholar]

- De Haro, L. News in marine toxicology. Ann. Toxicol. Anal. 2011, 23, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacups, S.P. Warmer waters in the Northern Territory—Herald an earlier onset to the annual Chironex fleckeri Stinger season. Ecohealth 2010, 7, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oiso, N.; Fukai, K.; Ishii, M.; Ohgushi, T.; Kubota, S. Jellyfish dermatitis caused by Porpita pacifica, a sign of global warming. Contact Dermat. 2005, 52, 232–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulware, D.R. A randomized controlled field trial for the prevention of jellyfish stings with a topical sting inhibitor. J. Travel Med. 2006, 13, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, R. Box jellyfish sting more than 300. Honolulu Star Bulletin. Available online: http://archives.starbulletin.com/2004/07/12/news/story5.html (accessed on 10 August 2012).

- Thomas, C.S.; Scott, S.A.; Galanis, D.J.; Goto, R.S. Box jellyfish (Carybdea alata) in Waikiki: Their influx cycle plus the analgesic effect of hot and cold packs on their stings to swimmers at the beach: A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. Hawaii Med. J. 2001, 60, 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Gershwin, L.; Dabinett, K. Comparison of eight types of protective clothing against Irukandji jellyfish stings. J. Coast. Res. 2009, 25, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariottini, G.L.; Pane, L. Mediterranean jellyfish venoms: A review on scyphomedusae. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 1122–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, S.K.; Tibballs, J. Australian Animal Toxins: The Creatures, Their Toxins and the Care of the Poisoned Patient, 2nd ed; Oxford University Press: Melbourne, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, E.H.; Marr, A.G. Sea wasp (Chironex fleckeri) venom: Lethal, hemolytic and dermonecrotic properties. Toxicon 1969, 7, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C. Mast Cell Secretion: Basis for Jellyfish Poisoning and Prospects for Relief. In Workshop on Jellyfish Blooms in the Mediterranean, Athens, Greece, 31 October–4 November 1983; pp. 63–73.

- Cormier, S.M. Exocytotic and cytolytic release of histamine from mast cells treated with Portuguese man-of-war (Physalia physalis) venom. J. Exp. Zool. 1984, 231, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, K.; Goldsmith, L.A.; Katz, S.I.; Gilchrest, B.A.; Paller, A.S.; Leffell, D.J. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine, 7th ed; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 2042–2045. [Google Scholar]

- Nimorakiotakis, B.; Winkel, K.D. Marine Envenomations Part 1—Jellyfsh. Aust. Fam. Physician. 2002, 32, 969–974. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, S.E.; Turner, R.J. Cardiovascular effects of toxins isolated from the cnidarian Chironex fleckeri Southcott. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1971, 41, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, M. First aid for jellyfish stings: Do we really know what we are doing? Emerg. Med. Australas. 2008, 20, 78–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, P.M.; Little, M.; Jelinek, G.A.; Wilce, J.A. Jellyfish envenoming syndromes: Unknown toxic mechanisms and unproven therapies. Med. J. Aust. 2003, 178, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, I. Adding confusion to first aid for jellyfish stings. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2008, 20, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagihara, A.A.; Kuroiwa, J.M.Y.; Oliver, L.M.; Kunkel, D.D. The ultrastructure of nematocysts from the fishing tentacle of the Hawaiian bluebottle, Physalia utriculus (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa, Siphonophora). Hydrobiologia 2002, 489, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daubert, P.G.; Plantz, S.H. Cnidaria Envenomation (2012). Available online: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/769538-overview (accessed on 5 February 2013).

- Fenner, P.J.; Williamson, J.A. Worldwide deaths and severe envenomations from jellyfish stings. Med. J. Aust. 1996, 165, 658–661. [Google Scholar]

- Halstead, B.W. Coelenterates. In Poisonous and Venomous Marine Animals of the World; Darwin Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1978; pp. 87–140. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzaga, R.A.F. Mordeduras picadas pot animas da forna Portuguesa. Premio Biol. Med. Clin. 1984, 165–167. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, J.W.; Fenner, P.J.; Kokelj, F.; Williamson, J.A. Serious Physalia (Portuguese Man O’ War) stings: Implications for scuba divers. J. Wilderness Med. 1994, 5, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, J.W. Treatment of Atlantic cnidarian envenomations. Toxicon 2009, 54, 1201–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loten, C.; Stokes, B.; Worsley, D.; Seymour, J.; Jiang, S.; Isbister, G. A randomised controlled trial of hot water (45 °C) immersion versus ice packs for pain relief in bluebottle stings. Med. J. Aust. 2006, 184, 329–333. [Google Scholar]

- Bowra, J.; Gillet, M.; Morgan, J.; Swinburn, E. A trial comparing hot showers and icepacks in the treatment of Physalia envenomation. Emerg. Med. 2002, 14, A22. [Google Scholar]

- Exton, D.R.; Fenner, P.J.; Williamson, J.A. Cold packs: Effective topical analgesia in the treatment of painful stings by Physalia and other jellyfish. Med. J. Aust. 1989, 15, 625–626. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, J.W.; Rubinstein, H.; Calton, G.J. First aid for jellyfish envenomation. South. Med. J. 1983, 76, 870–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.; Sullivan, P. Disarming the bluebottle: Treatment of Physalia envenomation. Med. J. Aust. 1980, 2, 394–395. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, J.W. Medical aspects of jellyfish envenomation: Pathogenesis, case reporting and therapy. Hydrobiology 2001, 451, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exton, D.R. Treatment of Physalia physalis envenomation. Med. J. Aust. 1988, 149, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Fenner, P.J.; Williamson, J.A.; Burnett, J.W.; Rifkin, J. First aid treatment of jellyfish stings in Australia. Response to a newly differentiated species. Med. J. Aust. 1993, 158, 498–501. [Google Scholar]

- Birsa, L.M.; Verity, P.G.; Lee, R.F. Evaluation of the effects of various chemicals on discharge of and pain caused by jellyfish nematocysts. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010, 151, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, N.T.; Darracq, M.A.; Tomaszewski, C.; Clark, R.F. Evidence-Based treatment of jellyfish stings in north America and Hawaii. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2012, 60, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwick, R. Disarming the box-jellyfish: Nematocyst inhibition in Chironex fleckeri. Med. J. Aust. 1980, 12, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, H.L. Portuguese Man-O’-War (“blue-bottle”) stings: Treatment with papain. Proc. Straub Clin. 1971, 37, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, J.W.; Williamson, J.A.; Fenner, P.J. Box jellyfish in Waikiki. Hawaii Med. J. 2001, 60, 278. [Google Scholar]

- Adiga, K.M. Brachial artery spasm as a result of a sting. Med. J. Aust. 1984, 140, 181–182. [Google Scholar]

- Gollan, J.A. The dangerous Portuguese Man-O’War. Med. J. Aust. 1968, 1, 973. [Google Scholar]

- Fish, C.J.; Cobb, M.C. Noxious marine animals of the central and western Pacific Ocean. Res. Rep. US Fish. Serv. 1954, 36, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Winkel, K.D.; Hawdon, G.M.; Fenner, P.J.; Gershwin, L.A.; Collins, A.G.; Tibballs, J. Jellyfish antivenoms: Past, present, and future. J. Toxic. 2003, 2, 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Southcott, R.V. Studies on Australian Cubomedusae, including a new genus and species apparently harmful to man. Aust. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1956, 7, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, P.J.; Harrison, S.L. Irukandji and Chironex fleckeri envenomation in tropical Australia. Wild. Environ. Med. 2000, 11, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suput, D. In vivo effects of cnidarian toxins and venoms. Toxicon 2009, 54, 1190–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, C.E.; Pockl, E.E.; Caltonm, G.J.; Burnett, J.W. Immunochromatographic purification of a nematocyst toxin from the cnidarian Chironex fleckeri (sea wasp). Toxicon 1984, 22, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, B.J. Clinical implications of research on the box jellyfish Chironex fleckeri. Toxicon 1994, 32, 1305–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.J.; Angus, J.A.; Winkel, K.D.; Wright, C.E. A pharmacological investigation of the venom extract of the Australian box jellyfish, Chironex fleckeri, in cardiac and vascular tissues. Toxicol. Lett. 2012, 209, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, B.J. Marine antivenoms. Clin. Toxicol. 2003, 41, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saggiomo, S.L.; Seymour, J.E. Cardiotoxic effects of venom fractions from the Australian box jellyfish Chironex fleckeri on human myocardiocytes. Toxicon 2012, 60, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, B.J. Clinical toxicology: A tropical Australian perspective. Ther. Drug Monit. 2000, 22, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, D.; Easton, R.G. Stingose, a new and effective treatment for bites and stings. Med. J. Aust. 1980, 2, 146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Carrette, T.J.; Cullen, P.; Little, M.; Pereira, P.L.; Seymour, J.E. Temperature effects on box jellyfish venom: A possible treatment for envenomed patients? Med. J. Aust. 2002, 177, 654–655. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, P.R.T.; Boyle, A.; Hartin, D.; McAuley, D. Is hot water immersion an effective treatment for marine envenomation? Emerg. Med. J. 2006, 23, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohman, E.B.; Bains, G.S.; Lohman, T.; de Leon, M.; Petrofsky, J.S. A comparison of the effect of a variety of thermal and vibratory modalities on skin temperature and blood flow in healthy volunteers. Med. Sci. Monit. 2011, 17, 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Watters, M.R.; Stommel, E.W. Marine neurotoxins: Envenomations and contact toxins. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2004, 6, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, S.; Isbister, G.K.; Seymour, J.E.; Hodgson, W.C. The in vivo cardiovascular effects of box jellyfish Chironex fleckeri venom in rats: Efficacy of pre-treatment with antivenom, verapamil and magnesium sulfate. Toxicon 2004, 43, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, P.J. Venomous jellyfish of the world. S. Pac. Underw. Med. Soc. (SPUMS) 2005, 35, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Nagai, H.; Takuwa-Kuroda, K.; Nakao, M.; Oshiro, N.; Iwanaga, S.; Nakajima, T.A. Novel protein toxin from the deadly box jellyfish (Sea Wasp, Habu-kurage) Chiropsalmus quadrigatus. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2002, 66, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershwin, L.A. Nematocysts of the Cubozoa. Zooacta 2006, 1232, 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, E.H.; Marr, A.G.M. Sea wasp (Chironex fleckeri) anti-venom: Neutralising potency against the venom of three other jellyfish species. Toxicon 1974, 12, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, S.; Isbister, G.K.; Seymour, J.E.; Hodgson, W.C. The in vitro effects of two chirodropid (Chironex fleckeri and Chiropsalmus sp.) venoms: Efficacy of box jellyfish antivenom. Toxicon 2003, 41, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, S.; Isbister, G.K.; Seymour, J.E.; Hodgson, W.D. Pharmacologically distinct cardiovascular effects of box jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri) venom and a tentacle-only extract in rats. Toxicol. Lett. 2005, 155, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.L.; Carrette, T.; Cullen, P.; Mulcahy, R.F.; Little, M.; Seymour, J. Pressure immobilisation bandages in first-aid treatment of jellyfish envenomation: Current recommendations reconsidered. Med. J. Aust. 2000, 173, 650–652. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, W. The occurrence of the jellyfish Chiropsalmus quadrumanus in Matagorda Bay, Texas. Bull. Mar. Sci. Gulf Caribb. 1959, 9, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Tibballs, J.; Li, R.; Tibballs, H.A.; Gershwin, L.A.; Winkel, K.D. Australian carybdeid jellyfish causing “Irukandji syndrome”. Toxicon 2012, 59, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecker, H. Irukandji sting to North Queensland bathers without production of wheals but with severe general symptoms. Med. J. Aust. 1952, 19, 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, J.H. Cause and effect in Irukandji stingings. Med. J. Aust. 1964, 1, 897–904. [Google Scholar]

- Fenner, P.J.; Williamson, J.; Callanan, V.I.; Audley, I. Further understanding of, and a new treatment for, “Irukandji” (Carukia barnesi) sting. Med. J. Aust. 1986, 145, 569–574. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto, C.M.; Yanagihara, A.A. Cnidarian (coelenterate) envenomations in Hawaii improve following Application heat. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2002, 9, 300–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, P.J.; Lewin, M. Sublingual glyceryl trinitrate as prehospital treatment for hypertension in Irukandji syndrome (letter). Med. J. Aust. 2003, 179, 655. [Google Scholar]

- Fenner, P.J.; Hadok, J.C. Fatal envenomation by jellyfish causing Irukandji syndrome. Med. J. Aust. 2002, 177, 362–363. [Google Scholar]

- Winkel, K.D.; Tibballs, J.; Molenaar, P.; Lambert, G.; Coles, P.; Ross-Smith, M.; Wiltshire, C.; Fenner, P.J.; Gershwin, L.A.; Hawdon, G.M.; et al. Cardiovascular actions of the venom from the Irukandji (Carukia barnesi) jellyfish: Effects in human, rat and guinea-pig tissues in vitro and in pigs in vivo. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2005, 32, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wright, C.E.; Winkel, K.D.; Gershwin, L.A.; Angus, I.A. The pharmacology of Malo maxima jellyfish venom extract in isolated cardiovascular tissues: A probable cause of the Irukandji syndrome in Western Australia. Toxicol. Lett. 2011, 201, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiong, K. Irukandji syndrome, catecholamines, and mid-ventricular stress cardiomyopathy. Eur. J. Echocardiogr. 2009, 10, 334–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, S.; Isbister, G.K.; Seymour, J.E.; Hodgson, W.C. The in vivo cardiovascular effects of the Irukandji jellyfish (Carukia barnesi) nematocyst venom and a tentacle extract in rats. Toxicol. Lett. 2005, 155, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.T.; Pereira, P.; Mulcahy, R.; Cullen, P.; Seymour, J.; Carrette, T.; Little, M. Severity of Irukandji syndrome and nematocyst identification from skin scrapings. Med. J. Aust. 2003, 178, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Nickson, C.P.; Waugh, E.B.; Jacups, S.P.; Currie, B.J. Irukandji syndrome case series from Australia’s tropical northern territory. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2009, 54, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pender, A.M.; Winkel, K.D.; Ligthelm, R.J. A probable case of Irukandji syndrome in Thailand. J. Travel Med. 2006, 13, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommier, P.; Coulange, M.; de Haro, L. Systemic envenomation by jellyfish in Guadeloupe: Irukandji-like syndrome? Med. Trop. (Mars) 2005, 65, 367–369. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Resuscitation Council—ARC (2010). Guideline 9.4.5. Envenomation—Jellyfish stings. Available online: http://www.resus.org.au/ (accessed on 19 February 2013).

- Fenner, P.J.; Williamson, J. Experiments with the nematocysts of Carybdea rastoni (“Jimble”). Med. J. Aust. 1987, 147, 258–259. [Google Scholar]

- Corkeron, M.A. Magnesium infusion to treat Irukandji syndrome. Med. J. Aust. 2003, 178, 411. [Google Scholar]

- Gershwin, L.A. Two new species of jellyfishes (Cnidaria: Cubozoa: Carybdeida) from tropical Western Australia, presumed to cause Irukandji syndrome. Zootaxa 2005, 1084, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Nomura, J.; Sato, R.L.; Ahern, R.M.; Snow, J.L.; Kuwaye, T.T.; Yamamoto, L.G. A randomized paired comparison trial of cutaneous treatments for acute jellyfish (Carybdea alata) stings. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2002, 20, 624–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.G. Treatment of jellyfish stings. Med. J. Aust. 2007, 186, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, C.S.; Scott, S.A.; Galanis, D.J.; Goto, R.D. Box jellyfish (Carybdea alata) in Waikiki: The analgesic effect of Sting-Aid, Adolph’s meat tenderizer and fresh water on their stings: A double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Hawaii Med. J. 2001, 60, 205–207. [Google Scholar]

- Fenner, P.J.; Fitzpatrick, P.F.; Hartwick, R.J.; Skinner, R. "Morbakka”, another cubomedusan. Med. J. Aust. 1985, 143, 550–555. [Google Scholar]

- Mariottini, G.L.; Giacco, E.; Pane, L. The mauve stinger Pelagia noctiluca (Forsskal, 1775). Distribution, ecology, toxicity and epidemiology of stings. A Review. Mar. Drugs 2008, 6, 496–513. [Google Scholar]

- De Donno, A.; Idolo, A.; Bagordo, F. Epidemiology of jellyfish stings reported to summer health centres in the Salento peninsula (Italy). Contact Dermat. 2009, 60, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togias, A.G.; Burnett, J.W.; Kagey-Sobotka, A.; Lichtenstein, L.M. Anaphylaxis after contact with a jellyfish. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1985, 75, 672–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, P.J.; Fitzpatrick, P.F. Experiments with the nematocysts of Cyanea capillata. Med. J. Aust. 1986, 145, 174. [Google Scholar]

- Salleo, A.; La Spada, G.; Falzea, G.; Denaro, M.G. Discharging effect of anions and inhibitory effect of divalent cations on isolated nematocysts of Pelagia noctiluca. Mol. Physiol. 1984, 5, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor, B. Cyanea capillata, Animal Diversity Web. Available online: http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Cyanea_capillata/ (accessed on 19 February 2013).

- Tønseth, K.A.; Andersen, T.S.; Karlsen, H.E. Jellyfish injuries. Tidsskr. Nor. Dr. Foren. (Nor.) 2009, 129, 1350. [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available online: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/epcsums/strengthsum.htm (accessed on 19 February 2013).

- Seymour, J.; Carrette, T.; Cullen, P.; Little, M.; Mulcahy, R.F.; Pereira, P.L. The use of pressure immobilisation bandages in Cubozoan envenomings. Toxicon 2002, 40, 1503–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, P.J.; Williamson, J.A.; Burnett, J. Pressure immobilization bandages in first-aid treatment of jellyfish envenomation: Current recommendations reconsidered. Med. J. Aust. 2001, 174, 665–666. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, K.L.; Isbister, G.K.; McGowan, S.; Konstantakopoulos, N.; Seymour, J.E.; Hodgson, W.C. A pharmacological and biochemical examination of the geographical variation of Chironex fleckeri venom. Toxicol. Lett. 2010, 192, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, P.K. Stingray injuries. Wilderness Environ. Med. 1997, 8, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muirhead, D. Applying pain theory in fish spine envenomation. S. Pac. Underw. Med. Soc. J. 2002, 32, 150–153. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Miranda-Massari, J.R.; Gonzalez, M.J.; Riordan, H.D. Intravenous ascorbic acid as a treatment for severe jellyfish stings. P. R. Health Sci. J. 2004, 23, 125–126. [Google Scholar]

- Currie, B. Box-Jellyfish in the Northern Territory. NT Dis. Control Bull. 1998, 5, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- QAS (Queensland Ambulance Service), Case Management Guidelines for Poisoning, Envenomation, Cuboidal Jellyfish. In Clinical Practice Manual; Queensland Ambulance Service: Brisbane, Australia, 1998.

- Kimball, A.B.; Arambula, K.Z.; Stauffer, A.R.; Levy, V.; Davis, V.W.; Liu, M.; Rehmus, W.E.; Lotan, A.; Auerbach, P.S. Efficacy of a jellyfish sting inhibitor in preventing jellyfish stings in normal volunteers. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2004, 15, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tønseth, K.A.; Andersen, T.S.; Pripp, A.H.; Karlsen, H.E. Prophylactic treatment of jellyfish stings—A randomised trial. Tidsskr. Nor. Laegeforen. 2012, 132, 1446–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, P.J.; Lippmann, J. Severe Irukandji-like jellyfish stings in Thai waters. Diving Hyperb. Med. 2009, 39, 175–177. [Google Scholar]

- Flomembaum, N.; Goldfrank, L.R.; Howland, M.A.; Lewin, N.A.; Hoffman, R.S.; Nelson, L.S.; Brush, D.E. Marine Envenomations. In Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies, 8th ed; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 1629–1642. [Google Scholar]

- Ping, J.; Onizuka, N. Epidemiology of jellyfish stings presented to an American urban emergency department. Hawaii Med. J. 2011, 70, 217–219. [Google Scholar]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Cegolon, L.; Heymann, W.C.; Lange, J.H.; Mastrangelo, G. Jellyfish Stings and Their Management: A Review. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 523-550. https://doi.org/10.3390/md11020523

Cegolon L, Heymann WC, Lange JH, Mastrangelo G. Jellyfish Stings and Their Management: A Review. Marine Drugs. 2013; 11(2):523-550. https://doi.org/10.3390/md11020523

Chicago/Turabian StyleCegolon, Luca, William C. Heymann, John H. Lange, and Giuseppe Mastrangelo. 2013. "Jellyfish Stings and Their Management: A Review" Marine Drugs 11, no. 2: 523-550. https://doi.org/10.3390/md11020523

APA StyleCegolon, L., Heymann, W. C., Lange, J. H., & Mastrangelo, G. (2013). Jellyfish Stings and Their Management: A Review. Marine Drugs, 11(2), 523-550. https://doi.org/10.3390/md11020523