Abstract

Recently, the studies on the antiviral activities of marine natural products, especially marine polysaccharides, are attracting more and more attention all over the world. Marine-derived polysaccharides and their lower molecular weight oligosaccharide derivatives have been shown to possess a variety of antiviral activities. This paper will review the recent progress in research on the antiviral activities and the mechanisms of these polysaccharides obtained from marine organisms. In particular, it will provide an update on the antiviral actions of the sulfated polysaccharides derived from marine algae including carrageenans, alginates, and fucans, relating to their structure features and the structure–activity relationships. In addition, the recent findings on the different mechanisms of antiviral actions of marine polysaccharides and their potential for therapeutic application will also be summarized in detail.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the constant outbreak of some emerging or reemerging viral diseases has caused serious harm to human health. During the last decade, the number of antivirals approved for clinical use has been increased from five to more than 30 drugs [1]. Despite these successes, drug efficacy, toxicity, and cost remained unresolved issues, which is particularly large in developing countries due to the relative unavailability of drugs and the continuous emergence of drug resistance. Hence, the development of novel antiviral agents that can be used alone or in combination with existing antivirals is of high importance.

Marine polysaccharides are very important biological macromolecules which widely exist in marine organisms. Marine polysaccharides present an enormous variety of structures and are still under-exploited, thus they should be considered as a novel source of natural compounds for drug discovery [2]. Marine polysaccharides can be divided into different types such as marine animal polysaccharides, plant polysaccharides and microbial polysaccharides according to their different sources. Marine derived polysaccharides have been shown to have a variety of bioactivities such as antitumor, antiviral, anticoagulant, antioxidant, immuno-inflammatory effects and other medicinal properties. In particular, the studies on the antiviral actions of marine polysaccharides and their oligosaccharide derivatives are attracting increasing interests, and marine polysaccharides are paving the way for a new trend in antiviral drugs.

This review presents an overview of recent progress in research on the antiviral activities of marine polysaccharides, relating to their structure features and structure–activity relationships. Moreover, this review will mainly focus on the heparinoid polysaccharides and the sulfated polysaccharides present in seaweed. Recent developments in the mechanisms of antiviral actions of marine polysaccharides and their oligosaccharide derivatives will also be discussed in detail.

2. The Classification and Main Structure Features of Marine Polysaccharides

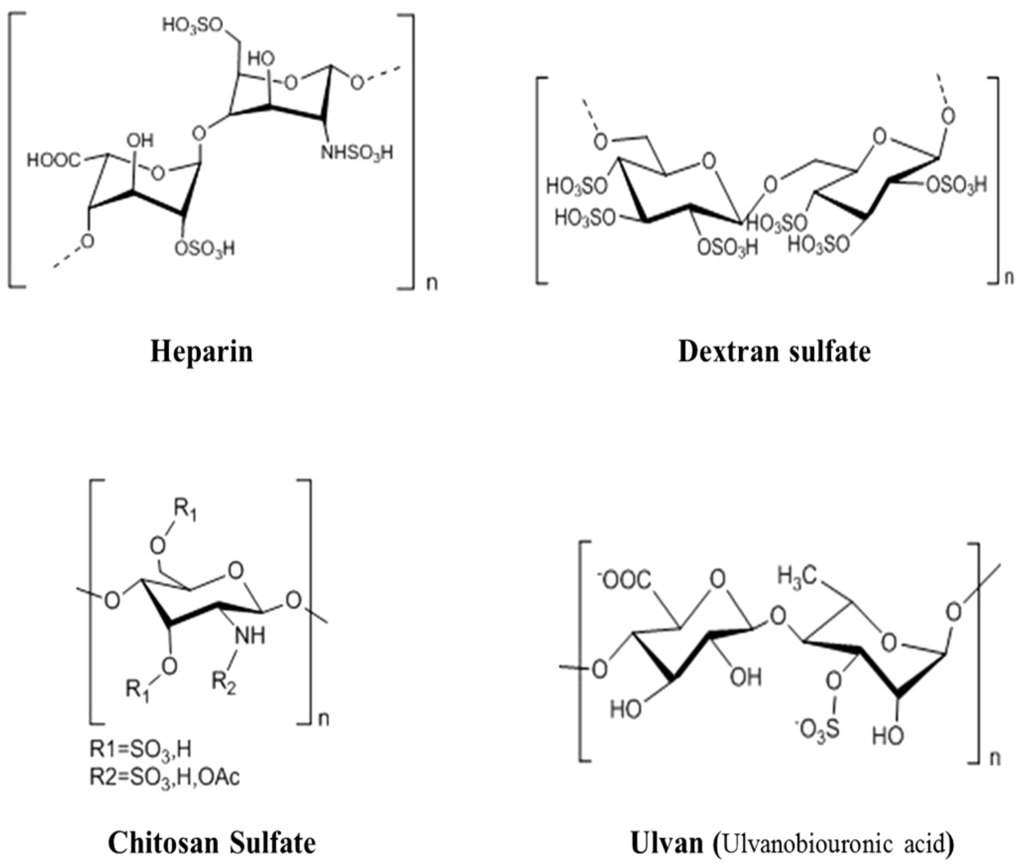

Marine polysaccharides usually exhibit structural features such as sulfate and uronic acid groups, which distinguish them from polysaccharides of terrestrial plants, but are similar to mammalian glycosaminoglycans, such as heparin and chondroitin sulfate [3]. Marine polysaccharides can be classified into three main types: marine animal polysaccharides, marine plant polysaccharides, and marine microbial polysaccharides according to their different sources, and each have different structure features.

2.1. The Main Structure Features of Marine Animal Polysaccharides

Marine animals are rich in polysaccharides, and the polysaccharides derived from marine fishes, shellfishes, and mollusks often possess a wide range of pharmacological activities [4]. The marine animal polysaccharides usually include chitosans derived from crustaceans, chondroitin sulfates from cartilaginous fishes, sulfated polysaccharides from sponge, and glycosaminoglycans from scallops and abalone [5,6].

Chitin, a long-chain polymer of N-acetylglucosamine, is one of the most abundant polysaccharides and usually prepared from the shells of crabs and shrimps [7,8]. Chitosan, a partially deacetylated polymer of N-acetylglucosamine, is produced commercially by deacetylation of chitin [9]. The molecular weight of commercially produced chitosan is usually between 3800 and 20,000 Daltons. Chitosan is a linear randomly distributed, hetero polysaccharide consisting of β-(1→4)-linked 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-D-glucopyranose and 2-amino-2-deoxy-D-glucopyranose units [2]. Chemical modification of chitin and chitosan can generate new biofunctional products which possess good biological activities and physicochemical properties [10,11,12,13,14]. Moreover, it was reported that the marine polysaccharides isolated from cartilaginous fishes also contain trace neutral mannose, xylose and rhamnose besides the galactosamine and glucuronic acid, which have certain structure-specific properties [15].

Furthermore, Cimino et al. [16] reported that rosacelose, a new anti-HIV polysaccharide composed of glucose and fucose sulfate, could be isolated from the aqueous extract of the marine sponge Mixylla rosacea. They also found that this marine polysaccharide has a linear polysaccharide structure mainly composed of 4,6-disulfated 3-O-glycosylated α-D-glucopyranosyl and 2,4-disulfated 3-O-glycosylated α-L-fucopyranosyl residues (in a 3:1 molar ratio) [16]. Moreover, it was reported that one kind of sugar polymer which contains hexosamine, hexuronic acid, and fucose sulfate could be separated from Apostichopus japonicus selenka [17]. In a word, marine animal polysaccharides have extremely broad distribution, and exist in almost all marine animal tissues and organs.

2.2. The Main Structure Features of Marine Plant Polysaccharides

The marine plant polysaccharides especially the seaweed polysaccharides are widely distributed in the ocean, occurring from the tide level to considerable depths, free-floating or anchored, which are the most abundant polysaccharides in marine organisms. Moreover, the polysaccharide content of seaweed is very high, accounting for more than 50% of the dry weight, thus the seaweed polysaccharides are very important resources for the development of marine polysaccharide drugs. The principal cell wall polysaccharides in green seaweeds are ulvans, those in red seaweeds are agarans and carrageenans, and those in brown seaweeds are alginates and fucans, as well as the storage polysaccharide laminarin [18,19].

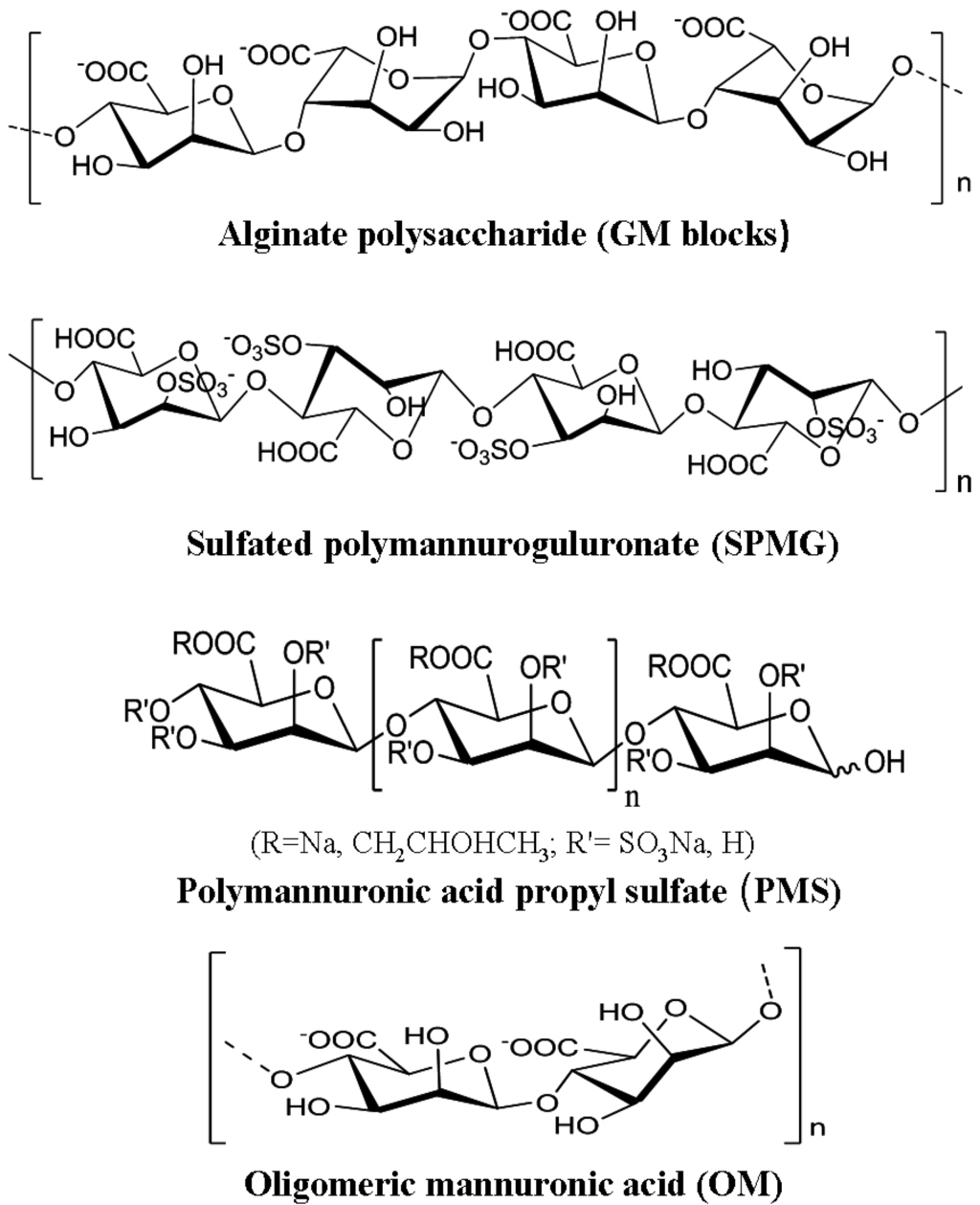

Alginates are the major constituent of brown seaweeds’ cell walls and are linear acidic polysaccharides composed with a central backbone of poly-D-glucuronic acid (G blocks), poly-D-mannuronic acid (M blocks) and alternate residues of D-guluronic acid and D-mannuronic acid (GM blocks) [20]. Fucans are also one of the major constituents of brown seaweed cell walls, and are ramified sulfated polysaccharides constituted by a central backbone of fucose sulfated in positions C2 and/or C4 and ramifications at each two or three fucose residues [21].

Red seaweed polysaccharides are primarily classified as agarans and carrageenans based on their stereochemistry, specifically galactans with 4-linked α-galactose residues of the L-series are termed agarans, and those of the D-series are termed carrageenans [22]. Carrageenans are sulfated D-galactans composed of repeating disaccharide units with alternating 3-linked β-D-galactopyranose (G-units) and 4-linked α-galactopyranose (D-units) or 3,6-anhydro-α-galactopyranose (AnGal-units), which possess broad-spectrum antiviral activities [18]. In conclusion, the seaweed polysaccharides are the most abundant polysaccharides in marine plants, and usually possess the special characteristics of high sulfation and carboxylation.

2.3. The Main Structure Features of Marine Microbial Polysaccharides

Marine microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and microalgae, are of considerable importance as promising new sources of a huge number of biologically active products [23,24,25,26]. Some of these marine species live in high-pressure, high-salt, low-temperature, and oligotrophic environments, which provide the opportunity for them to produce unique active substances that differ from the terrestrial ones [27].

Marine microbial polysaccharides, especially the extracellular polysaccharides, have structural diversity, complexity, and particularity. Most of these polysaccharides are heteropolysaccharides which composed by different monosaccharides in a certain percentage, wherein the glucose, galactose and mannose are the most common components in microbial polysaccharides. It was reported that spirulan, a sulfated polysaccharide isolated from Arthrospira platensis (formely Spirulina platensis) is composed of two types of disaccharide repeating units, [→3)-α-L-Rha(1→2)-α-L-Aco-(1→] where Aco (acofriose) is 3-O-methyl-Rha with sulfate groups and O-hexuronosyl-rhamnose [28].

In addition, the marine microbial polysaccharides also contain glucuronic acid, galacturonic acid, amino sugars, and pyruvate. Roger et al. [29] reported that the exopolysaccharide (EPS) derived from marine bacterium Alteromonas infernus is a highly branched acidic heteropolysaccharide with a high molecular weight and low sulfate content (less than 10%). Its nonasaccharide repeating unit is composed of uronic acid (galacturonic and glucuronic acid) and neutral sugars (galactose and glucose), and substituted with one sulfate group [29]. In conclusion, the marine microbial polysaccharides with novel chemical compositions and structure features have been found to possess potential applications in fields such as pharmaceuticals, food additives, and industrial waste treatments.

5. Conclusions

During the last decade, numerous bioactive polysaccharides with interesting functional properties have been discovered from marine organisms [111]. Marine polysaccharides, especially the sulfated polysaccharides derived from marine algae, often possess good inhibitory effects on a variety of viruses [18,112]. This review mainly focuses on the antiviral activities and mechanisms of marine polysaccharides, which is expected to attract more interest for future explorations. The antiviral activities of most marine polysaccharides are usually related to the specific sugar structure, molecular weights and their degree of sulfation. Marine polysaccharides can inhibit the replication of viruses through interfering with a few steps in virus life cycle or improving the host antiviral immune responses to accelerate the process of viral clearance. Despite having good antiviral effects, marine polysaccharides are structurally diverse and heterogeneous, which makes studies of their structures challenging, and may also have hindered their development as therapeutic agents to date [18].

In conclusion, marine polysaccharides, especially the polysaccharides derived from seaweed, have many advantages, such as relatively low production costs, broad spectrum of antiviral properties, low cytotoxicity, and wide acceptability, which suggest marine polysaccharides merit further investigation as promising antivirals that can be used alone or in combination with existing drugs [113]. Until now, most of the studies on antiviral effects of marine polysaccharides have been observed in vitro or in mouse model systems. Therefore, further studies are needed in order to investigate their antiviral activities in human subjects [60]. Moreover, the structure–activity relationships and the underlying molecular mechanisms of antiviral actions of marine polysaccharides need to be understood precisely and elucidated clearly by intensive studies in the future [111].

Acknowledgments

We thank Lijuan Zhang (Ocean University of China, China) for her helpful advice and critical readings of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (IRT0944), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31271923), Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2011HQ012), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (201113013), the Special Fund for Marine Scientific Research in the Public Interest (201005024), and Qingdao science and technology development project (12-1-4-1-(20)-jch).

References

- De Clercq, E. Antiviral drugs in current chemical reviews. J. Clin. Virol. 2004, 30, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurienzo, P. Marine polysaccharides in pharmaceutical applications: An overview. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 2435–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, G.L.; Yu, G.L.; Wang, W.; Zhao, X.L.; Zhang, J.Z.; Stephen, H.E. Properties of polysaccharides in several seaweeds from Atlantic Canada and their potential anti-influenza viral activities. J. Ocean Univ. China 2012, 11, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.L.; Zheng, T.L. Studies on polysaccharides from marine organism, a review. Mar. Sci. 2004, 28, 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.; Ray, A.R. Biomedical applications of chitin, chitosan, and their derivative. J. Macromol. Sci. 2000, 40, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zierer, M.S.; Mourao, P.S. A wide diversity of sulfated polysaccharides are synthesized by different species of marine sponges. Carbohydr. Res. 2000, 328, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, D.N.; Kim, M.M.; Kim, S.K. Chitin oligosaccharides inhibit oxidative stress in live cells. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008, 74, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, F.; Louime, C.; Abazinge, M.; Onokpise, O. Extraction and evaluation of chitin from crub exoskeleton as a seed fungicide and plant growth enhancer. Am. Eurasian J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2007, 2, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.K.; Nghiep, N.D.; Rajapakse, N. Therapeutic prospectives of chitin, chitosan and their derivatives. J. Chitin Chitosan 2006, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jayakumar, R.; New, N.; Nagagama, H.; Furuike, T.; Tamura, H. Synthesis, characterization and biospecific degradation behavior of sulfated chitin. Macromol. Symp. 2008, 264, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwan, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, B.; Vongchan, P.; Meepowpan, P.; Zhang, F.; Mousa, S.A.; Mousa, S.; Premanode, B.; Kongtawelert, P.; et al. Sulfonation of papain-treated chitosan and its mechanism for anticoagulant activity. Carbohydr. Res. 2009, 344, 1190–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Ao, Q.; Wang, A.; Gong, Y.; Zhao, N.; Zhang, X. In vitro cytotoxicity and protein drug release properties of chitosan/heparin microspheres. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2007, 12, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thierry, B.; Merhi, Y.; Silver, J.; Tabrizian, M. Biodegradable membrane-covered stent from chitosan-based polymers. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2005, 75, 556–566. [Google Scholar]

- Prabaharan, M.; Reis, R.L.; Mano, J.F. Carboxymethyl chitosan-graft-phosphatidylethanolamine: Amphiphilic matrices for controlled drug delivery. React. Funct. Polym. 2007, 67, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, R.P.; Leyva, A.; Moraes, M.O. Shark cartilage as source of antiangiogenic compounds: From basic to clinical research. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2001, 24, 1097–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimino, P.; Bifulco, G.; Casapullo, A.; Bruno, I.; Gomez-Paloma, L.; Riccio, R. Isolation and NMR characterization of rosacelose, a novel sulfated polysaccharide from the sponge Mixylla rosacea. Carbohydr. Res. 2001, 334, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.L.; Zheng, Z.H.; Su, W.J.; Chen, F.; Wu, P.R.; Fang, J.R. Studies on the chemical composition of sea cucumber mensamar intercede III. Immunomodulative effects of PMI-1. Mar. Sci. Bull. 2001, 20, 88–91. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, G.; Yu, G.; Zhang, J.; Ewart, S.H. Chemical structures and bioactivities of sulphated polysaccharides from marine algae. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 196–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, L.E.; Turgeon, S.L.; Beaulieu, M. Characterization of polysaccharides extracted from brown seaweeds. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007, 69, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabeau, S.; Kloareg, B. Isolation and analysis of the cell walls of brown algae: Fucus spiralis, F. ceranoides, F. vesiculosus, F. serratus, Bifurcaria bifurcata and Laminaria digitata. J. Exp. Bot. 1986, 38, 1573–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Wei, X.; Zhao, R. Fucoidans: Structure and bioactivity. Molecules 2008, 13, 1671–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutsen, S.H.; Myslabodski, D.E.; Larsen, B.; Usov, A.I. A modified system of nomenclature for red algal galactans. Bot. Mar. 1994, 37, 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Xu, F.; Shao, C.; She, Z.; Lin, Y.; Chan, W.L. Bioactive Metabolites from Marine Microorganisms. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Atta-ur-Rahman, F.R.S., Ed.; Elsevier Science Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 197–310. [Google Scholar]

- Debbab, A.; Aly, A.H.; Lin, W.H.; Proksch, P. Bioactive compounds from marine bacteria and fungi. Microb. Biotechnol. 2010, 3, 544–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, A.L.; Hill, R.T.; Place, A.R.; Hamann, M.T. The expanding role of marine microbes in pharmaceutical development. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2010, 21, 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.R.A.; Kaulekar, D.P.; Lokabarathi, P.A. Marine drugs from sponge microbe association: A review. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 1417–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.L.; Hong, H.S.; Wang, F.; Maskaoui, K.; Su, J.; Tian, Y. The distribution characters of bacteria β-glucosidase activity in the Taiwan Strait. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2002, 45, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.B.; Hayashi, T.; Hayashi, K.; Sankawa, U. Structural analysis of calcium spirulan (Ca-SP)-derived oligosaccharides using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, O.; Kervarec, N.; Ratiskol, J.; Colliec-Jouault, S.; Chevolot, L. Structural studies of the main exopolysaccharide produced by the deep-sea bacterium Alteromonas infernus. Carbohydr. Res. 2004, 339, 2371–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCandless, E.L.; Craigie, J.S. Sulphated polysaccharides in red and brown algae. Planta 1979, 112, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahaye, M. Developments on gelling algal galactans, their structure and physico-chemistry. J. Appl. Phycol. 2001, 13, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.H.; Chan, Y.L.; Tsai, L.W.; Li, T.L.; Wu, C.J. Prevention of human enterovirus 71 infection by kappa carrageenan. Antivir. Res. 2012, 95, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talarico, L.B.; Damonte, E.B. Interference in dengue virus adsorption and uncoating by carrageenans. Virology 2007, 363, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassauer, A.; Weinmuellner, R.; Meier, C.; Pretsch, A.; Prieschl-Grassauer, E.; Unger, H. Iota-Carrageenan is a potent inhibitor of rhinovirus infection. Virol. J. 2008, 5, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, M.J.; Scolaro, L.A.; Noseda, M.D.; Cerezo, A.S.; Damonte, E.B. Protective effect of a natural carrageenan on genital herpes simplex virus infection in mice. Antivir. Res. 2004, 64, 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Leibbrandt, A.; Meier, C.; König-Schuster, M.; Weinmüllner, R.; Kalthoff, D.; Pflugfelder, B.; Graf, P.; Frank-Gehrke, B.; Beer, M.; Fazekas, T.; et al. Iota-carrageenan is a potent inhibitor of influenza A virus infection. PLoS One 2010, 5, e14320. [Google Scholar]

- Talarico, L.B.; Noseda, M.D.; Ducatti, D.R.B.; Duarte, M.E.; Damonte, E.B. Differential inhibition of dengue virus infection in mammalian and mosquito cells by iota-carrageenan. J. Gen. Virol. 2011, 92, 1332–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, C.B.; Thompson, C.D.; Roberts, J.N.; Muller, M.; Lowy, D.R.; Schiller, J.T. Carrageenan is a potent inhibitor of papillomavirus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2006, 2, e69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Ogamo, A.; Saito, T.; Uchiyama, H.; Nakagawa, Y. Preparation of O-acylated low-molecular-weight carrageenans with potent anti-HIV activity and low anticoagulant effect. Carbohydr. Polym. 2000, 41, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Ogamo, A.; Saito, T.; Watanabe, J.; Uchiyama, H.; Nakagawa, Y. Preparation and anti-HIV activity of low-molecular-weight carrageenans and their sulfated derivatives. Carbohydr. Polym. 1997, 32, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Wang, L.C.; Wu, H.; Luan, H.M. Bio-function summary of marine oligosaccharides. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2011, 3, 74–86. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, F.; Chen, F.; Li, F. Preparation and potential in vivo anti-influenza virus activity of low molecular-weight κ-carrageenans and their derivatives. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, P.; Hao, C.; Zhang, X.E.; Cui, Z.Q.; Guan, H.S. In vitro inhibitory effect of carrageenan oligosaccharide on influenza A H1N1 virus. Antivir. Res. 2011, 92, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, P.; Yu, G.L.; Li, C.X.; Hao, C.; Qi, X.; Zhang, L.J.; Guan, H.S. Preparation and anti-influenza A virus activity of κ-carrageenan oligosaccharide and its sulphated derivatives. Food Chem. 2012, 133, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damonte, E.B.; Matulewicz, M.C.; Cerezo, A.S. Sulfated seaweed polysaccharides as antiviral agents. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004, 11, 2399–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, M.J.; Ciancia, M.; Matulewicz, M.C.; Cerezo, A.S.; Damonte, E.B. Antiherpetic activity and mode of action of natural carrageenans of diverse structural types. Antivir. Res. 1999, 43, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Girond, S.; Crance, J.M.; van Cuyck-Gandre, H.; Renaudet, J.; Deloince, R. Antiviral activity of carrageenan on hepatitis A virus replication in cell culture. Res. Virol. 1991, 142, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talarico, L.B.; Pujol, C.A.; Zibetti, R.G.; Faría, P.C.; Noseda, M.D.; Duarte, M.E.; Damonte, E.B. The antiviral activity of sulfated polysaccharides against dengue virus is dependent on virus serotype and host cell. Antivir. Res. 2005, 66, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, R.M.; Cecconi, O.; Roberts, W.G.; Aruffo, A.; Linhardt, R.J.; Bevilacqua, M.P. Heparin oligosaccharides bind L- and P-selectin and inhibit acute inflammation. Blood 1993, 82, 3253–3258. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M.S.; Ali, S.; Rix, D.A.; Zhang, J.G.; Kirby, J.A. Endothelial production of MCP-1: Modulation by heparin and consequences for mononuclear cell activation. Immunology 1997, 92, 512–518. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Garg, H.G.; Li, B.; Linhardt, R.J.; Hales, C.A. Antitumor effect of butanoylated heparin with low anticoagulant activity on lung cancer growth in mice and rats. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2010, 10, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, R.; Balasubramaniam, A.; Tiwari, V.; Zhang, F.; Bridges, A.; Linhardt, R.J.; Shukla, D.; Liu, J. Using a 3-O-sulfated heparin octasaccharide to inhibit the entry of herpes simplex virus type 1. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 5774–5783. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Kuri, M.; Barron Romero, B.L.; Aguilar-Setien, A. Inhibition of three alpha herpes viruses (herpes simplex 1 and 2 and pseudo rabies virus) by heparin, heparan and other sulfated polyelectrolytes. Arch. Med. Res. 1996, 27, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Neyts, J.; Snoeck, R.; Schols, D.; Balzarini, J.; Esko, J.D.; van Schepdael, A.; de Clercq, E. Sulfated polymers inhibit the interaction of human cytomegalovirus with cell surface heparan sulfate. Virology 1992, 189, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, K.; Matsuzaki, T.; Sugahara, Y.; Okada, J.; Hasebe, M.; Iwamura, Y.; Ohnishi, M.; Kanno, T.; Shimizu, M.; Honda, E. BHV-1 adsorption is mediated by the interaction of glycoprotein gIII with heparinlike moiety on the cell surface. Virology 1991, 181, 666–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kari, B.; Gehrz, R. A human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein complex designated gC-II is a major heparin-binding component of the envelope. J. Virol. 1992, 66, 1761–1764. [Google Scholar]

- Madeleine, L.M.; Reinhard, G. Dextran sulfate inhibits the fusion of influenza virus with model membranes, and suppresses influenza virus replication in vivo. Antivir. Res. 1990, 14, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witvrouw, M.; Schols, D.; Andrei, G.; Snoeck, R.; Hosoya, M.; Pauwels, R.; Balzarini, J.; de Clercq, E. Antiviral activity of low-MW dextran sulphate (derived from dextran MW 1000) compared to dextran sulphate samples of higher MW. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 1991, 2, 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, V.; Rouseva, R.; Kolarova, M.; Serkedjieva, J.; Rachev, R.; Manolova, N. Isolation of a polysaccharide with antiviral effect from Ulva lactuca. Prep. Biochem. 1994, 24, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.-S.; Kim, S.-K. Potential anti-HIV agents from marine resources: An overview. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 2871–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.L.; Geng, M.Y.; Guan, H.S.; Li, Z.L. Study on the mechanism of inhibitory action of 911 on replication of HIV-1 in vitro. Chin. J.Mar. Drugs 2000, 19, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, X.L.; Ding, H.; Geng, M.Y.; Liang, P.F.; Li, Y.X.; Guan, H.S. Studies of the anti-AIDS effects of marine polysaccharide drug 911 and its related mechanisms of action. Chin. J. Mar. Drugs 2000, 6, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, M.Y.; Li, F.C.; Xin, X.L.; Li, J.; Yan, Z.W.; Guan, H.S. The potential molecular targets of marine sulfated polymannuroguluronate interfering with HIV-1 entry Interaction between SPMG and HIV-1 gp120 and CD4 molecule. Antivir. Res. 2003, 59, 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, B.C.; Geng, M.Y.; Li, J.; Li, F.; Chen, H.; Guan, H.S.; Ding, J. Sulfated polymannuroguluronate, a novel anti-acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) drug candidate, targeting CD4 in lymphocyte. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004, 68, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Geng, M.Y.; Xin, X.L.; Li, F.C.; Chen, H.X.; Guan, H.S.; Ding, J. Multiple and multivalent interactions of novel anti-AIDS drug candidates, sulfated polymannuronate (SPMG)-derived oligosaccharides, with gp120 and their anti-HIV activitie. Glycobiology 2005, 15, 501–510. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, B.F.; Xu, X.F.; Li, L.; Yuan, W. Study on “911” anti-HBV effect in HepG2.2.15 cells culture. Mod. Prev. Med. 2003, 30, 517–518. [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz, K.C.S.; Medeiros, V.P.; Queiroz, L.S.; Abreu, L.R.D.; Rocha, H.A.O.; Ferreira, C.V.; Juca, M.B.; Aoyama, H.; Leite, E.L. Inhibition of reverse transcriptase activity of HIV by polysaccharides of brown algae. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2008, 62, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidari, K.I.P.J.; Takahashi, N.; Arihara, M.; Nagaoka, M.; Morita, K.; Suzuki, T. Structure and anti-dengue virus activity of sulfated polysaccharide from a marine alga. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 376, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akamatsu, E.; Shimanaga, M.; Kamei, Y. Isolation of an anti-influenza virus substance, MC26 from a marine brown alga Sargassum piluliferum and its antiviral activity against influenza virus. Coast. Bioenviron. 2003, 1, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Muto, S.; Niimura, K.; Oohara, M.; Oguchi, Y.; Matsunaga, K.; Hirose, K.; Kakuchi, J.; Sugita, N.; Furusho, T. Polysaccharides from marine algae and antiviral drugs containing the same as active ingredients. Eur. Patent EP295956, 21 December 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, N.; Liu, S.; Han, J.J.; Sun, F.S. The depressive effect of glycosaminoglycan from scallop on type-I herpes simplex virus. Acta Acad. Med. Qingdao Univ. 2008, 2, 111–114. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.F.; Li, J.B.; Hou, G.; Huang, D.N. Study on the inhibition effects of Perna viridis polysaccharides on influenza virus reproduction in MDCK cell cultures. Mod. Med. J. China 2008, 5, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.M.; Xu, W.M.; Xu, Z.; Lin, F.; Sheng, L. Antiviral effect of oyster extract compound capsule in ducks infected by DHBV. Chin. Pharm. J. 1996, 31, 304–307. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, E.R.; Kim, W.S.; Kim, Y.S. Virus-cell fusion inhibitory activity for the polysaccharides from various Korean edible clams. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2001, 24, 514–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.; Zivanovic, S.; D’Souza, D.H.; Davidson, M.P. Effectiveness of chitosan on the inactivation of enteric viral surrogates. Food Microbiol. 2012, 32, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospieszny, H.; Chirkov, S.; Atabekov, J. Induction of antiviral resistance in plants by chitosan. Plant Sci. 1991, 79, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydova, V.N.; Nagorskaia, V.P.; Gorbach, V.I.; Kalitnik, A.A.; Reunov, A.V.; Solov’eva, T.F.; Ermak, I.M. Chitosan antiviral activity: Dependence on structure and depolymerization method. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2011, 47, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Chirkov, S.N. The antiviral activity of chitosan (review). Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2002, 38, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikov, S.N.; Chirkov, S.N.; Il’ina, A.V.; Lopatin, S.A.; Varlamov, V.P. Effect of the molecular weight of chitosan on its antiviral activity in plants. Prik. Biokhim. Mikrobiol. 2006, 42, 224–228. [Google Scholar]

- Sosa, M.A.; Fazely, F.; Koch, J.A.; Vercellotti, S.V.; Ruprecht, R.M. N-carboxymethylchitosan-N,O-sulfate as an anti-HIV-1 agent. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1991, 174, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, S.I.; Kai, H.; Shinada, K.; Yoshida, T.; Tokura, S.; Kurita, K.; Nakashima, H.; Yamamoto, N.; Uryu, T. Regioselective syntheses of sulfated polysaccharides: Specific anti-HIV-1 activity of novel chitin sulfates. Carbohydr. Res. 1998, 306, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.L.; Tan, C.Y.; Du, Y.G.; Bai, X.F.; Wang, K.Y.; Ma, X.J. Effects of chitooligosaccharides on rabbit neutrophils in vitro. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007, 69, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.J.; Kim, S.K. Continuous production of chitooligosaccharides using a dual reactor system. Process Biochem. 2000, 35, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.J.; Kim, S.K. Production of chitooligosaccharides using ultrafiltration membrane reactor and their antibacterial activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2000, 41, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artan, M.; Karadeniz, F.; Karagozlu, M.Z.; Kim, M.M.; Kim, S.K. Anti-HIV-1 activity of low molecular weight sulfated chitooligosaccharides. Carbohydr. Res. 2010, 345, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospieszny, H.; Atabekov, J.G. Effect of chitosan on the hypersensitive reaction of bean to alfalfa mosaic virus. Plant Sci. 1989, 62, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.S. New drug—Polymannuronic acid propyl sulfates. China Patent 93100608.2, 6 July 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, H.S. New drug—polymeric mannuronic acids sulfate. China Patent 95110396.2, 2 October 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Yu, G.L.; Hao, C.; Guan, H.S. The application of one kind of oligomeric mannuronic acid in the preparation of anti-influenza A H1N1 virus drugs. China Patent 201110408962.7, 9 December 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Li, C.X.; Guan, H.S.; Yu, G.L.; Wang, S.X. The application of polymannuronic acid propyl sulfate in the preparation of drugs against influenza A (H1N1) virus. China Patent 201210201876.3, 18 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kanekiyo, K.; Hayashi, K.; Takenaka, H.; Lee, J.B.; Hayashi, T. Anti-herpes simplex virus target of an acidic polysaccharide, nostoflan, from the edible blue-green alga Nostoc flagelliforme. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 30, 1573–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Yim, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, W.G.; Kim, S.J.; Kang, P.S.; Lee, C.K. In vitro inhibition of influenza A virus infection by marine microalga-derived sulfated polysaccharide p-KG03. Antivir. Res. 2012, 93, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, M.J.; Scolaro, L.A.; Damonte, E.B. Herpes simplex virus type 1variants arising after selection with an antiviral carageenan: Lack of correlation between drug susceptibility and synphenotype. J. Med. Virol. 2002, 68, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harden, E.A.; Falshaw, R.; Carnachan, S.M.; Kern, E.R.; Prichard, M.N. Virucidal activity of polysaccharide extracts from four algal species against herpes simplex virus. Antivir. Res. 2009, 83, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.W.; Zivanovic, S.; D’Souza, D.H. Effect of chitosan on the infectivity of murine norovirus, feline calicivirus, and bacteriophage MS2. J. Food Protect. 2009, 72, 2623–2628. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder, S.; Ghosal, P.K.; Pujol, C.A.; Carlucci, M.J.; Damonte, E.B.; Ray, B. Isolation, chemical investigation and antiviral activity of polysaccharides from Gracilaria corticata (Gracilariaceae, Rhodophyta). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2002, 31, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, M.J.; Pujol, C.A.; Ciancia, M.; Noseda, M.D.; Matulewicz, M.C.; Damonte, E.B.; Cerezo, A.S. Antiherpetic and anticoagulant properties of carrageenans from the red seaweed Gigartina skottsbergii and their cyclized derivatives: Correlation between structure and biological activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1997, 20, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, M.J.; Scolaro, L.A.; Damonte, E.B. Inhibitory action of natural carrageenans on herpes simplex virus infection of mouse astrocytes. Chemotheraphy 1999, 45, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinchero, J.; Ponce, N.M.; Córdoba, O.L.; Flores, M.L.; Pampuro, S.; Stortz, C.A.; Salomón, H.; Turk, G. Antiretroviral activity of fucoidans extracted from the brown seaweed Adenocystis utricularis. Phytother. Res. 2009, 23, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, S.C.; Reynaldi, S.; Stortz, C.A.; Cerezo, A.S.; Damonte, E.B. Antiviral properties of fucoidan fractions from Leathesia difformis. Phytomedcine 1999, 6, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majczak, G.A.H.; Richartz, R.R.T.B.; Duarte, M.E.R.; Noseda, M.D. Antiherpetic Activity of Heterofucans Isolated from Sargassum stenophyllum (Fucales, Phaeophyta). In Proceedings of the 17th International Seaweed Symposium, Cape Town, South Africa, 28 January–2 February 2001; Chapman, A.R.O., Anderson, R.J., Vreeland, V.J., Davison, I.R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Ponce, N.M.A.; Pujol, C.A.; Damonte, E.B.; Flores, M.L.; Stortz, C.A. Fucoidans from the brown seaweed Adenocystis utricularis: Extraction methods, antiviral activity and structural studies. Carbohydr. Res. 2003, 338, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, M.; Snoeck, R.; Pauwels, R.; de Clercq, E. Sulfated polysaccharides are potent and selective inhibitors of various enveloped viruses, including herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, vesicular stomatitis virus, and human immunodeficiency virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1988, 32, 1742–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, J.; Schelhaas, M.; Helenius, A. Virus entry by endocytosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010, 79, 803–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talarico, L.B.; Duarte, M.E.R.; Zibetti, R.G.M.; Noseda, M.D.; Damonte, E.B. An algal-derived DL-galactan hybrid is an efficient preventing agent for in vitro dengue virus infection. Planta Med. 2007, 73, 1464–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.E.; Alarcón, B.; Carrasco, L. Polysaccharides as antiviral agents: Antiviral activity of carrageenan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1987, 31, 1388–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, E.V.; Sonnenfeld, G. Interferon induction by the immunomodulating polyanion Lambda carrageenan. Infect. Immun. 1979, 25, 467–469. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.; Sun, Y.P.; Xin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, Z. In vivo antitumor and immunomodulation activities of different molecular weight lambda-carrageenans from Chondrus ocellatus. Pharmacol. Res. 2004, 50, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.M.; Song, J.M.; Li, X.G.; Li, X.G.; Li, N.; Dai, J.C. Immunomodulation and antitumor activity of κ-carrageenan oligosaccharides. Cancer Lett. 2006, 243, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-K.; Cho, M.L.; Karnjanapratum, S.; Shin, I.-S.; You, S.G. In vitro and in vivo immunomodulatory activity of sulfated polysaccharides from Enteromorpha prolifera. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2011, 49, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S. Therapeutic importance of sulfated polysaccharides from seaweeds: Updating the recent findings. 3 Biotech 2012, 2, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witvrouw, M.; de Clercq, E. Sulfated polysaccharides extracted from sea algae as potential antiviral drugs. Gen. Pharm. 1997, 29, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T.; Chattopadhyay, K.; Marschall, M.; Karmakar, P.; Mandal, P.; Ray, B. Focus on antivirally active sulfated polysaccharides: From structure-activity analysis to clinical evaluation. Glycobiology 2009, 19, 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Samples Availability: Available from the authors.

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).