1. Introduction

Modern operative gynecology advocates for implementing minimally invasive and rapid treatment above all [

1,

2,

3]. The ability to quickly diagnose and take necessary action contributes to the patient’s experience, as they often “don’t have that much time” to evaluate their situation negatively. Therefore, the sooner treatment is applied, the greater the chance that the patient will, over time, forget what happened and return to normal life after the procedure and recovery [

4].

Any patient qualifying for a procedure within operative gynecology faces various types of discomfort over an extended period that significantly impair their comfort and quality of life. Therefore, the opportunity to undergo treatment and a procedure that can greatly reduce their discomfort positively impacts how they view their future life. Patient quality of life, both after and even before surgery, is influenced by the treatment itself and the planned surgical intervention. It is important to note that the diagnostic process and the diagnosis of the disease affect the patient’s mood, often leading to lowered spirits or even depression [

5,

6,

7]. Any side effects associated with the treatment also significantly shape the patient’s perception of their situation within the treatment process [

8].

Patients requiring surgical treatment represent a particularly demanding group requiring a specialized approach characterized by understanding and empathy for the emotions they experience [

9]. According to several studies, the extent and manner in which information about the diagnosis and related treatment methods is communicated can enhance cooperation with the patient. This improved cooperation is reflected in better collaboration with the medical team, increased satisfaction with care, and a greater sense of control over the situation [

6]. For this reason, it is not surprising that these women are eager to obtain all the information that is most important to them regarding the disease necessitating surgical treatment and the actions doctors will take before and after the operation, along with their purposes [

4].

It is important to note that one element affecting the assessment of the quality of life of female patients may be the ubiquitous cult of the body in modern culture [

10]. The diagnosis of an illness requiring surgery (even laparoscopic methods) can realistically contribute to a decrease in quality of life for these patients [

11,

12]. This situation can be difficult for those around them to understand, as, in the context of the disease itself, it may not seem so significant; after all, the most important aspect is the health and life of the patient [

8]. In conclusion, it can be stated that every patient has the right to feel uncomfortable about their discomfort, have concerns regarding their health and treatment, and demand that all information about their treatment be communicated to them.

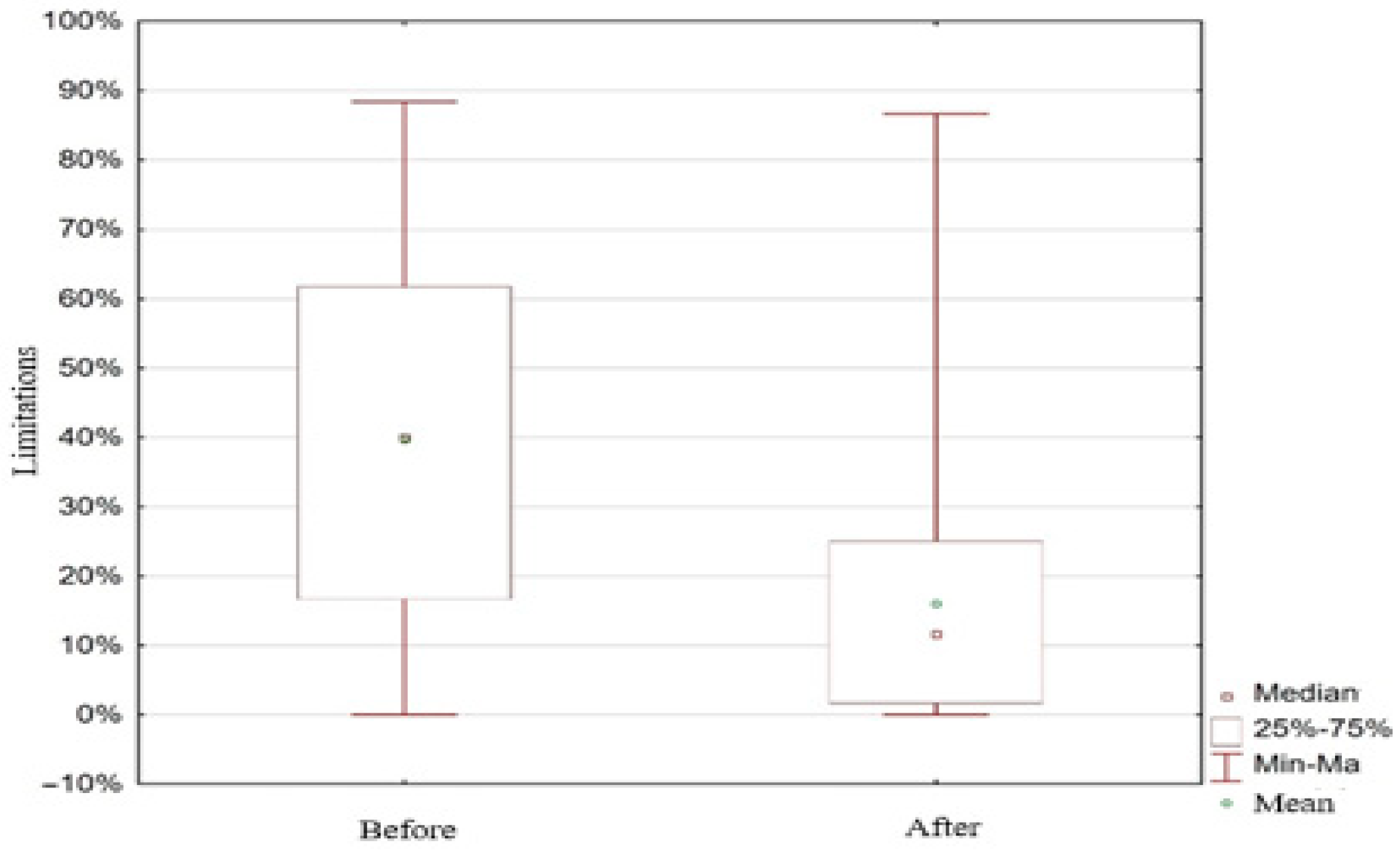

This study aims to assess the changes in quality of life among women undergoing minimally invasive surgical treatments for gynecological diseases. The proposed tool allowed us to collect detailed information regarding functional limitations, social roles, and subjective health perceptions pre- and post-intervention.

2. Materials and Methods

This study included 150 patients admitted to the Minimally Invasive Pelvic Surgery Center at Heliodor Święcicki Gynecological and Obstetrics Clinical Hospital of the Karol Marcinkowski Medical University in Poznań, Poland, for surgery using minimally invasive techniques.

2.1. Procedure of Qualifying Patients for Surgery

The criterion for participation was eligibility for surgery, as determined by a prior gynecological examination. Patients were qualified for the procedure following a gynecological and ultrasound (USG) examination and after completing a medical history.

2.2. Data Collecting

This study was conducted from January to June 2022, utilizing two questionnaires to assess the quality of life of female patients before surgery and 1 month after surgery. The study group were assured of complete anonymity and voluntary participation.

Each respondent was required to complete the questionnaire twice—before the surgery and 1 month after the surgery—indicating whether their quality of life had changed. Data from nine women were discarded from the study due to incomplete responses.

For the purpose of this study, we created our own two questionnaires to assess women’s quality of life related to their ailments. The patients completed the first questionnaire before the operation, and the second one was completed 1 month after. The questions were designed to best analyze the topics covered by this study’s thesis.

The first survey included questions about the reason for visiting the Minimally Invasive Pelvic Surgery Center at Heliodor Święcicki Gynecological and Obstetrics Clinical Hospital, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, how the patient learned about the possibility of surgery (How did you hear about the Center for Minimally Invasive Pelvic Surgery? Is the outcome of another treatment outside the Center for Minimally Invasive Pelvic Surgery a consequence of the outcome? What made you choose the Center for Minimally Invasive Pelvic Surgery? Would you recommend the Center for Minimally Invasive Pelvic Surgery to another patient?), the duration and severity of their symptoms, their opinion of the medical and obstetric staff (How would you recommend medical work at the facility? How would you recommend nursing work at the facility?), and their socioeconomic conditions and the impact of the disease (0—non, 1—small, 2—average, 3—big, 4—very big, 5—not applicable) on particular aspects of life (a Working life, b Social life, c Playing sports, d Sexual intercourse, e Enjoying hobbies, f Having children, g Dressing in favorite way, h Using public transportation, i Driving a car, j Having a partner, k Going out shopping, l Going for a long walk, m Keeping body weight within the normal range, n Carrying out previously intended plans, o Controlling daily expenses). The second survey focused mainly on comparing quality of life after surgery to that in the period before surgery (poor, moderate, good, very good).

This study used a self-developed questionnaire created specifically for the clinical context of the Minimally Invasive Pelvic Surgery Center. The tool was designed to capture patient experiences before and after surgery, with a focus on functional limitations, emotional state, and quality of life. Although not validated against standardized tools such as SF-36 or EQ-5D, it allowed us to obtain targeted insight into the patient population to which it was administered. The use of a non-validated instrument may limit generalizability and comparability with studies using standardized QoL measures. However, the use of non-validated questionnaires is not a weakness; it is required in these modern times of living online and on social media. This limitation is acknowledged in the discussion and should be considered when interpreting the results.

The second survey focused mainly on comparing the quality of life after surgery with that before surgery. This study was approved by the local Bioethics Committee (No 178/21).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical Analysis: For continuous variables such as quality of life (QoL) scores and limitation levels, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare pre- and postoperative results. Group comparisons for non-parametric continuous data were performed using the Mann–Whitney U-test or Kruskal–Wallis test. For categorical data, such as age groups, occupation, and type of diagnosis, associations were examined using the Chi-square (χ2) test. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to evaluate relationships between non-parametric continuous variables. The study group included a heterogeneous population: patients with uterine myomas (23.5%), urinary incontinence (19%), pelvic organ prolapse (14.5%), endometriosis (11%), and other undefined gynecological conditions—benign tumors of the ovaries, e.g., teratoma, mucous, or simple cyst (24%). While this reflects real-world clinical diversity, the large proportion of “other” diagnoses limits the clinical specificity of the results, and conclusions regarding this category should be considered purely exploratory.

For data analysis, we used TIBCO Software Inc. (2017) (Palo Alto, CA, USA), Statistica (data analysis software system, version 13), and Microsoft Excel (version 2019) from Microsoft Office. The Mann–Whitney U-test and Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA test were employed for comparisons between the groups. Pre-treatment and post-treatment results were compared using the Wilcoxon paired-rank order test. The relationship between variables was examined using Spearman’s R-test and Chi2 NW (highest reliability). The significance level in all calculations was set at p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

Quality of life in medicine has long been a significant concern, primarily pondered by physicians and all other medical personnel. This is particularly relevant in areas of medicine where both the conditions being treated are characterized by a high degree of pain experienced by patients, and the treatments themselves can contribute to a temporary reduction in the quality and efficiency of patients’ lives [

13]. Such a situation also applies to women struggling with various gynecological diseases, including the respondents in this study.

Many studies utilize validated measures to assess changes in quality of life after surgery, such as the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) [

14], the EuroQol Health Survey (EQ-5D) [

15], or the Veterans RAND 12-item Health Survey (VR-12) [

16]. Another method involves simply asking patients how their quality of life changed after surgery, often referred to as a “global assessment” measure [

17,

18]. Following surgery and anesthesia, patients can be classified based on their QoR-15 score [

19]. Both methods aim to measure the same construct, namely health-related quality of life. Validated measures are more objective as they inquire about concrete factors contributing to quality of life; however, they can be time-consuming to administer. In contrast, the global measure is quicker to administer but more subjective [

20]. In the study conducted, we used our own questionnaire, adapted to the clinical situation of the patients. This approach provided an opportunity to gain insights into their overall health status, living conditions, and recovery process.

Women of all ages are treated at the Minimally Invasive Pelvic Surgery Center at the Gynecological and Obstetrics Clinical Hospital in Poznań, Poland. For the most part, these age groups align with those noted by other researchers: women over the age of 50 most often seek treatment for urinary incontinence, while younger women typically present with endometriosis and/or uterine myomas [

21]. Importantly, occupationally active women were significantly more likely to seek surgery for the removal of uterine myomas or endometriosis [

22]. Women with endometriomas reported significantly more problems in the areas of “paid work” (

p < 0.001), “housework” (

p < 0.001), social life (

p < 0.001), and sexual life (

p < 0.001), as well as problems in continuing hobbies (

p < 0.001) and spending leisure time (

p < 0.001) [

23]. Factors such as being professionally inactive [

22], patient age (

p = 0.0001), body mass index (BMI) (

p = 0.0001), and the surgical procedure for the removal of the uterus via laparotomy (

p = 0.0001) exert the greatest effect on the occurrence of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in premenopausal and postmenopausal women [

24].

This study found that the majority of the examined women who underwent minimally invasive surgical techniques (laparoscopic) rated their quality of life as good. This result is mainly attributed to women suffering from various gynecological conditions for an extended period, after receiving appropriate treatment and undergoing the procedure, experiencing significant improvement in their health [

21,

25,

26]. First and foremost, this improvement is related to the pain experienced by the patients, as well as various limitations, such as an inability to carry out heavier shopping or participate in sports [

21].

Accordingly, the surgery the subjects underwent positively impacted their lives, primarily improving their quality of life. The most important positive aspect of the surgery/procedure is that most of the participants stopped experiencing pain, allowing them to resume many of their normal life activities. This, in turn, led the women to feel no regret about their decision to undergo the procedure.

The type of surgical method also affects the length of hospitalization; the longest average hospitalization time was observed in the group of women operated on via laparotomy, with an average of 5.29 days. In contrast, the hospitalization time was more than half as short in the group of women operated on laparoscopically, averaging 2.45 days [

21]. Recovery times lengthened with increasing levels of physical burden, as well as with the invasiveness of the surgery [

27]. Thus, the type of surgery performed and the shorter hospitalization time associated with the laparoscopic technique realistically affect the better quality of life of patients after the procedure [

28]. Another important element of quality of life for women after surgery is the need for convalescence and the various inconveniences associated with it. Psychological factors, demographic factors, and perioperative outcomes are important predictors of recovery quality and convalescence duration. Increased recovery quality is associated with a shorter convalescence period [

29,

30]. When a woman requires surgery, she primarily considers the need for a long hospital stay associated with both preparation for the procedure and recovery after the operation. Despite the fact that this time is significantly reduced today and that surgical treatments are becoming less invasive, it is important to note that many patients still experience a kind of “suspension” in their lives. Some patients are on long-term sick leave [

31], and the awareness of being unable to carry out daily activities—particularly those related to work and family life—can significantly affect how a woman perceives her situation and assesses her quality of life. The level of their quality of life has improved or may improve after the procedure, which is clearly related to the relief experienced by the patients [

32].

Patients who underwent surgery using minimally invasive techniques rated their quality of life as good. The treatment positively impacted their daily functioning. In most cases, the women reported a significant reduction in pain and the ability to engage in activities they had given up on due to their condition. The most common complaints reported were widespread discomfort and the need for regular doctor visits for check-ups or treatments. The respondents did not regret their decision to undergo the procedure. This is primarily due to the significant improvement in their quality of life and their ability to return to daily activities. The level of their quality of life improved or may improve after the procedure, which is clearly related to the relief they experienced.

Study limitations: The questionnaire was developed specifically for our study population (the Minimally Invasive Pelvic Surgery Center at Heliodor Święcicki Gynecological and Obstetrics Clinical Hospital of the Karol Marcinkowski Medical University in Poznań, Poland); the lack of validation against standard instruments (SF-36, EQ-5D) limits the comparability of results and the generalizability of conclusions, calling for cautious interpretation of the findings. Consequently, the model’s results or predictions may be difficult to trust or explain, as the apparent relationships may not hold beyond the specific dataset used. However, the use of questionnaires that have not been validated is not a weakness of our work; such are the demands of our times of living online and on social media.