Health-Related Quality of Life, Illness Perception, Stigmatization and Optimism Among Hematology Patients: Two Exploratory Path Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Type

2.2. Sample

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Relationships

3.2. Exploratory Path Models

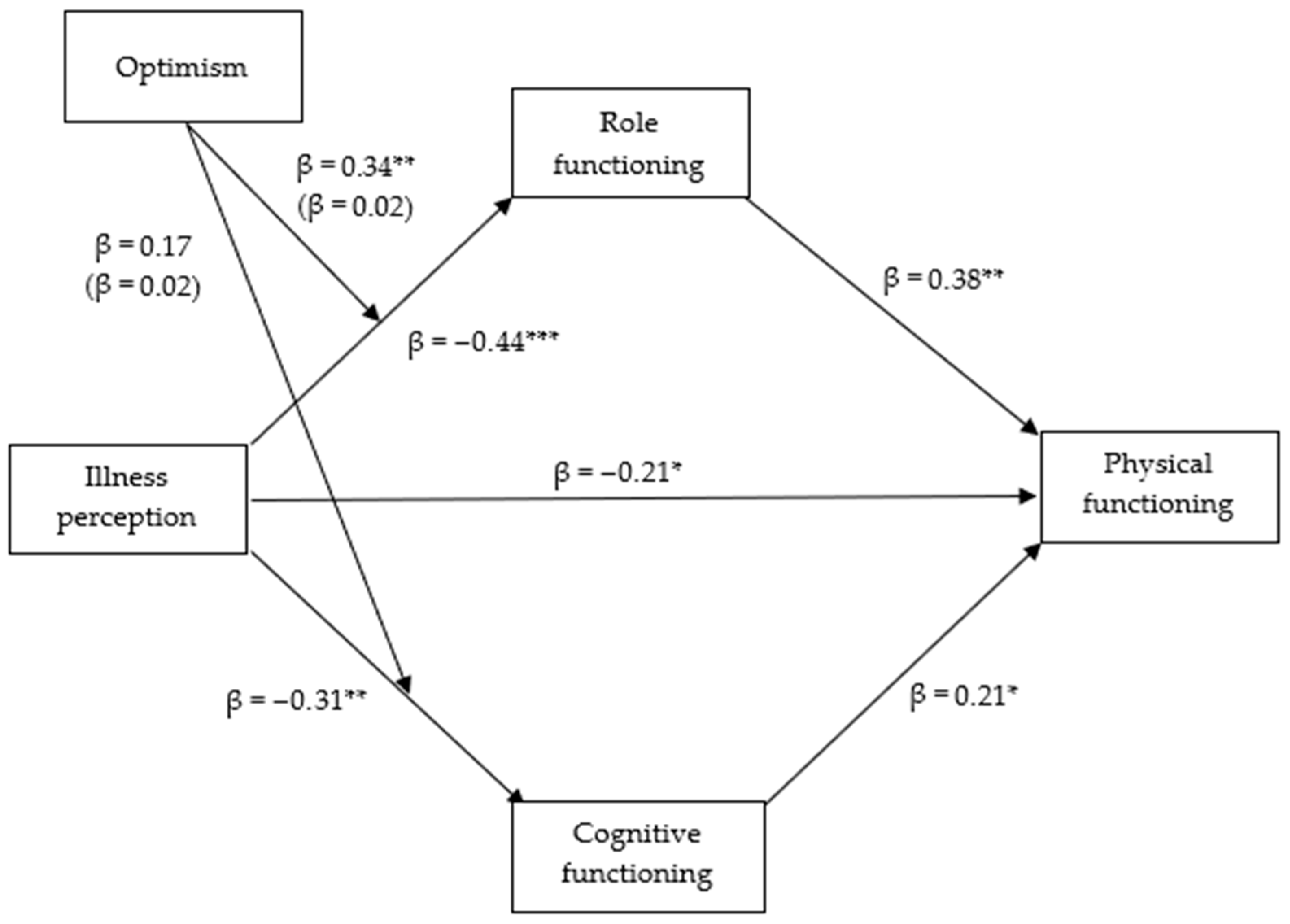

3.2.1. Path Model for Physical Functioning

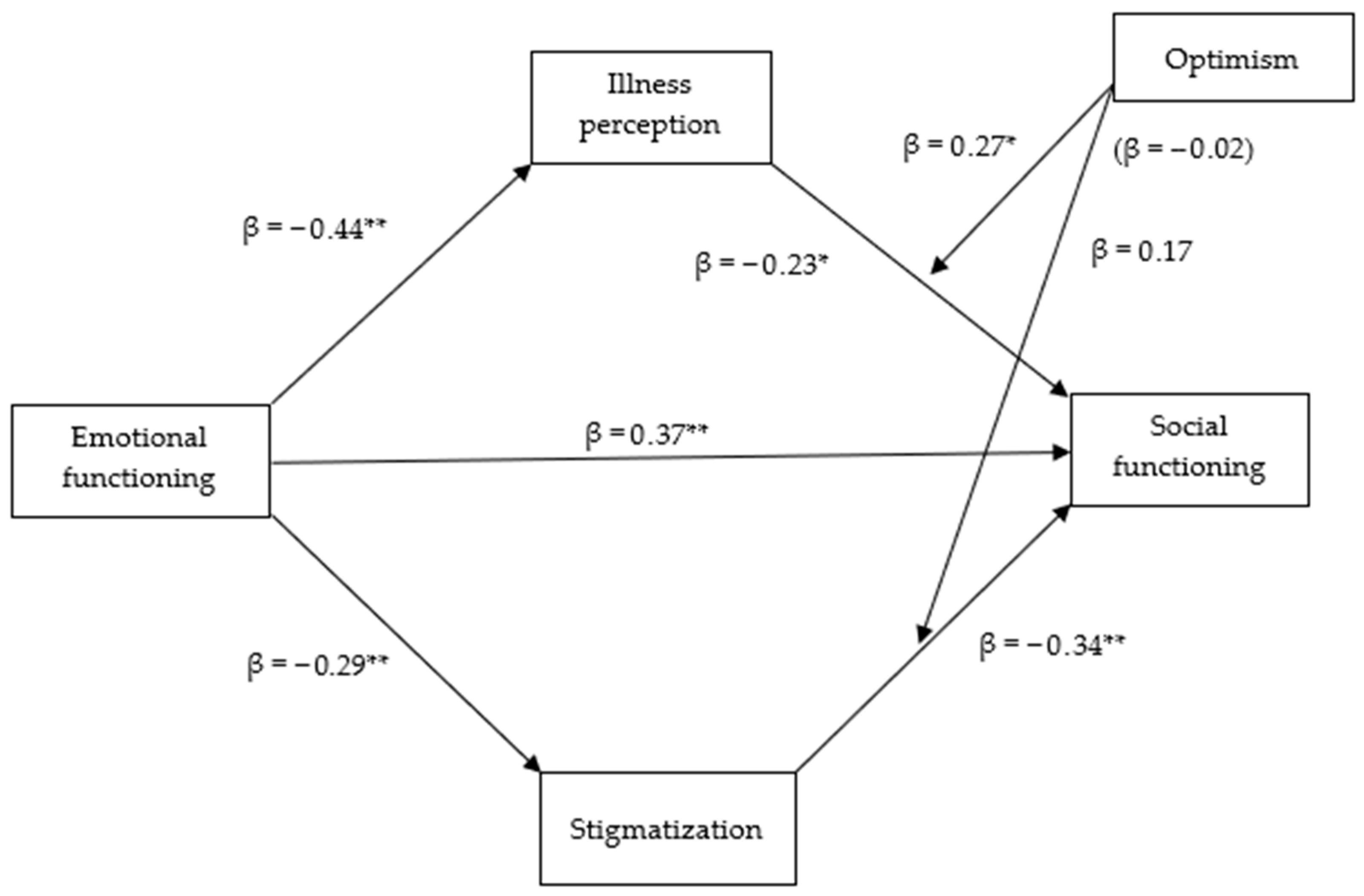

3.2.2. Path Model for Social Functioning

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, N.; Wu, J.; Wang, Q.; Liang, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, G.; Ma, L.; Liu, X.; Zhou, F. Global burden of hematologic malignancies and evolution patterns over the past 30 years. Blood Cancer J. 2023, 13, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youron, P.; Singh, C.; Jindal, N.; Malhotra, P.; Khadwal, A.; Jain, A.; Prakash, G.; Varma, N.; Varma, S.; Lad, D.P. Quality of life in patients of chronic lymphocytic leukemia using the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-CLL17 questionnaire. Eur. J. Haematol. 2020, 105, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, I.B.; Cleary, P.D. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life: A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA 1995, 273, 59–65. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7996652/ (accessed on 2 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ojelabi, A.O.; Graham, Y.; Haighton, C.; Ling, J. A systematic review of the application of Wilson and Cleary health-related quality of life model in chronic diseases. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrans, C.E.; Zerwic, J.J.; Wilbur, J.E.; Larson, J.L. Conceptual model of health-related quality of life. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2005, 37, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakas, T.; McLennon, S.M.; Carpenter, J.S.; Buelow, J.M.; Otte, J.L.; Hanna, K.M.; Ellett, M.L.; Hadler, K.A.; Welch, J.L. Systematic review of health-related quality of life models. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2012, 10, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, N.G.; Maddocks, K.J.; Johnson, A.J.; Byrd, J.C.; Westbrook, T.D.; Andersen, B.L. Cancer-specific stress and trajectories of psychological and physical functioning in patients with relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ann. Behav. Med. 2018, 52, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.K.; Lu, C.Y.; Yao, Y.; Chiang, C.Y. Social functioning, depression, and quality of life among breast cancer patients: A path analysis. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2023, 62, 102237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhamss, M.M.; Mathbout, L.F.; Nassri, R.B.; Alabdaljabar, M.S.; Hashmi, S.; Muhsen, I.N. Quality of life in hematologic malignancy in the eastern Mediterranean region: A systematic review. Cureus 2022, 14, e32436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, A.T.; Tholstrup, D.; Petersen, M.A.; Pedersen, L.; Groenvold, M. Health-related quality of life in a nationally representative sample of haematological patients. Eur. J. Haematol. 2009, 83, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.E.; Scherer, S.; Wiskemann, J.; Steindorf, K. Return to work after breast cancer: The role of treatment-related side effects and potential impact on quality of life. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, e13051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydın Sayılan, A.; Demir Doğan, M. Illness perception, perceived social support, and quality of life in patients with diagnosis of cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2020, 29, e13252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Rodríguez, I.; Hombrados-Mendieta, I.; Melguizo-Garín, A.; Martos-Méndez, M.J. The importance of social support, optimism, and resilience on the quality of life of cancer patients. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 833176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ośmiałowska, E.; Staś, J.; Chabowski, M.; Jankowska-Polańska, B. Illness perception and quality of life in patients with breast cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porkert, S.; Lehner-Baumgartner, E.; Valencak, J.; Knobler, R.; Riedl, E.; Jonak, C. Patients’ illness perception as a tool to improve individual disease management in primary cutaneous lymphomas. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 2018, 98, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Li, X. Understanding public-stigma and self-stigma in the context of dementia: A systematic review of the global literature. Dementia 2020, 19, 148–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, J.; Mehnert, A.; Dietz, A.; Hornemann, B.; Esser, P. Perceived stigmatization and its impact on quality of life: Results from a large register-based study including breast, colon, prostate, and lung cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzun, S.; Ediz, C.; Mohammadnezhad, M. Hematology patients’ metaphorical perceptions of the disease and psychosocial support needs in the treatment process: A phenomenological study from a rural region of Türkiye. Support Care Cancer 2025, 33, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, R.P.; Haywood, C., Jr. Sickle cell trait diagnosis: Clinical and social implications. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program. 2015, 2015, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F. Dispositional optimism. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2014, 18, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colby, D.A.; Shifren, K. Optimism, mental health, and quality of life: A study among breast cancer patients. Psychol. Health Med. 2013, 18, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oken, M.M.; Creech, R.H.; Tormey, D.C.; Horton, J.; Davis, T.E.; McFadden, E.T.; Carbone, P.P. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 1982, 5, 649–655. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7165009/ (accessed on 4 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castaños-Cervantes, S.; Domínguez-González, A. Depression in Mexican medical students: A path model analysis. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silpakit, C.; Sirilerttrakul, S.; Jirajarus, M.; Sirisinha, T.; Sirachainan, E.; Ratanatharathorn, V. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30): Validation study of the Thai version. Qual. Life Res. 2006, 15, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Látos, M.; Lázár, G.; Csabai, M. A Rövid Betegségpercepció Kérdőív magyar változatának megbízhatósági vizsgálata [The reliability and validity of the Hungarian version of the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire]. Orvosi Hetil. 2021, 162, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmermans, I.; Versteeg, H.; Meine, M.; Pedersen, S.S.; Denollet, J. Illness perceptions in patients with heart failure and an implantable cardioverter defibrillator: Dimensional structure, validity, and correlates of the brief illness perception questionnaire in Dutch, French and German patients. J. Psychosom. Res. 2017, 97, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szőcs, H.; Horváth, Z.; Vizin, G. A szégyen mediációs szerepe a stigma és az életminőség kapcsolatában coeliakiában szenvedő betegek körében: A 8 tételes Stigmatizáció Krónikus Betegségekben Kérdőív magyar adaptálás [The Hungarian adaptation of the Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness-8: Shame mediates the relationship between stigma and quality of life among patients with coeliac disease]. Orvosi Hetil. 2021, 162, 1968–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bérdi, M.; Köteles, F. Az optimizmus mérése: Az Életszemlélet Teszt átdolgozott változatának (LOT–R) pszichometriai jellemzői hazai mintán. [The measurement of optimism: The psychometric properties of the Hungarian version of the Revised Life Orientation Test (LOT–R)]. Hung. J. Psychol. 2010, 65, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, A.; Schulte, T.; Finck, C.; Gómez, Y.; Brähler, E.; Zenger, M.; Körner, A.; Tibubos, A.-N. Psychometric evaluations of the Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R), based on nine samples. Psychol. Health 2022, 37, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ames, S.C.; Lange, L.; Ames, G.E.; Heckman, M.G.; White, L.J.; Roy, V.; Foran, J.M. A prospective study of the relationship between illness perception, depression, anxiety, and quality of life in hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e6906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekarakou, C.; Koulierakis, G.; Pontikoglou, C. Illness perceptions and illness outcomes in patients with hematologic diseases: A narrative review. Psychology 2024, 15, 444–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, A.; Asnani, V.; Leger, R.R.; Harris, J.; Odesina, V.; Hemmings, D.L.; Morris, D.A.; Knight-Madden, J.; Wagner, L.; Asnani, M.R. Stigma and illness uncertainty: Adding to the burden of sickle cell disease. Hematology 2018, 23, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allart-Vorelli, P.; Porro, B.; Baguet, F.; Michel, A.; Cousson-Gélie, F. Haematological cancer and quality of life: A systematic literature review. Blood Cancer J. 2015, 5, e305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, K.; Koç, Z. Stigmatization, discrimination and illness perception among oncology patients: A cross-sectional and correlational study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 54, 102000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amonoo, H.L.; Barclay, M.E.; El-Jawahri, A.; Traeger, L.N.; Lee, S.J.; Huffman, J.C. Positive psychological constructs and health outcomes in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients: A systematic review. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019, 25, e5–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megari, K. Quality of life in chronic disease patients. Health Psychol. Res. 2013, 1, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, S.R.; Apputhurai, P.; Jenkins, Z.; O’fLaherty, E.; Ierino, F.; Langham, R.; Ski, C.F.; Thompson, D.R.; Castle, D.J. Impact of chronic kidney disease on illness perceptions, coping, self-efficacy, psychological distress and quality of life. Psychol. Health Med. 2023, 28, 1963–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, T.D.; Morrison, E.J.; Maddocks, K.J.; Awan, F.T.; Jones, J.A.; Woyach, J.A.; Johnson, A.J.; Byrd, J.C.; Andersen, B.L. Illness perceptions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Testing Leventhal’s self-regulatory model. Ann. Behav. Med. 2019, 53, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.S.; Fielding, R. Quality of life and pain in Chinese lung cancer patients: Is optimism a moderator or mediator? Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Applebaum, A.J.; Stein, E.M.; Lord-Bessen, J.; Pessin, H.; Rosenfeld, B.; Breitbart, W. Optimism, social support, and mental health outcomes in patients with advanced cancer. Psychooncology 2014, 23, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, B.; Ludwig, H.; Bailey, A.; Khela, K.; Marongiu, A.; Carlson, K.B.; Rider, A.; Seesaghur, A. Physical, emotional and social pain communication by patients diagnosed and living with multiple myeloma. Pain Manag. 2022, 12, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.; Shi, S.; Li, C.; Ruan, C. The influence of social constraints on the quality of life of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation survivors: The chain mediating effect of illness perceptions and the fear of cancer recurrence. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1017561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n (%) | Mean (SD) Median/Range Min–Max | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological sex | |||

| Female | 54 (56.3) | ||

| Male | 42 (43.8) | ||

| Age (years) | 56.45 (15.55) 62/62 21–83 | ||

| 18–49 | 29 (30.2) | ||

| 50–64 | 30 (31.3) | ||

| 65– | 37 (38.5) | ||

| Educational status | |||

| Primary education | 35 (36.5) | ||

| Secondary education | 36 (37.5) | ||

| Tertiary education or higher | 25 (26.0) | ||

| Permanent residence (number of residents) | |||

| Village or smaller (0–5000) | 26 (27.1) | ||

| Small town (5–20,000) | 23 (24.1) | ||

| Medium town (20–100,000) | 25 (26.1) | ||

| Large city (>100,000) | 22 (22.9) | ||

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| Lower and lower middle class | 32 (33.3) | ||

| Middle class | 55 (57.3) | ||

| Upper middle and upper class | 9 (9.4) | ||

| Type of disease | |||

| Leukemias and chronic myeloproliferative disease | 52 (54.2) | ||

| Lymphomas | 32 (33.3) | ||

| Multiple myeloma | 9 (9.4) | ||

| Other non-malignant diseases (ET, PNH, TTP) | 3 (3.1) | ||

| Health condition (ECOG status 0–5) | 0.48 (0.69) 0–2 | ||

| 0—fully active, able to carry on all pre-disease performance without restriction | 58 (60.4) | ||

| 1—Restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to carry out work of a light or sedentary nature, e.g., light housework, office work | 30 (31.3) | ||

| 2—Ambulatory and capable of all selfcare but unable to carry out any work activities; up and about more than 50% of waking hours | 8 (8.3) | ||

| Construct and Item Description | Loading | α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illness perception | – | 0.64 | 0.91 | 0.60 |

| IP1 | 0.78 | |||

| IP2 | 0.94 | |||

| IP3 | 0.80 | |||

| IP4 | 0.73 | |||

| IP5 | 0.59 | |||

| IP6 | 0.81 | |||

| IP7 | 0.56 | |||

| IP8 | 0.86 | |||

| Stigmatization | – | 0.75 | 0.89 | 0.54 |

| STIG1 | 0.87 | |||

| STIG2 | 0.99 | |||

| STIG3 | 0.82 | |||

| STIG4 | 0.62 | |||

| STIG5 | 0.89 | |||

| STIG6 | 0.40 | |||

| STIG7 | 0.59 | |||

| STIG8 | 0.48 | |||

| Optimism | – | 0.72 | 0.90 | 0.51 |

| OPT1 | 0.65 | |||

| OPT2 | 0.74 | |||

| OPT3 | 0.69 | |||

| OPT4 | 0.62 | |||

| OPT5 | 0.58 | |||

| OPT6 | 0.88 | |||

| OPT7 | 0.78 | |||

| OPT8 | 0.69 | |||

| OPT9 | 0.82 | |||

| OPT10 | 0.58 | |||

| Physical functioning | – | 0.78 | 0.91 | 0.69 |

| PH1 | 0.75 | |||

| PH2 | 0.83 | |||

| PH3 | 0.92 | |||

| PH4 | 0.61 | |||

| PH5 | 0.98 | |||

| Role functioning | – | 0.87 | 0.74 | 0.59 |

| R1 | 0.99 | |||

| R2 | 0.89 | |||

| Emotional functioning | – | 0.85 | 0.74 | 0.58 |

| EF1 | 0.76 | |||

| EF2 | 0.78 | |||

| EF3 | 0.82 | |||

| EF4 | 0.68 | |||

| Cognitive functioning | – | 0.61 | 0.79 | 0.65 |

| CF1 | 0.98 | |||

| CF2 | 0.60 | |||

| Social functioning | – | 0.79 | 0.73 | 0.59 |

| SF1 | 0.88 | |||

| SF1 | 0.99 |

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Range (Min–Max) | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Illness perception | 40.52 (11.86) | 57 (10–67) | (0.64) | |||||||

| 2. Stigmatization | 10.87 (3.49) | 21 (8–29) | 0.19 | (0.79) | ||||||

| 3. Optimism | 37.05 (4.75) | 23 (26–49) | −0.29 ** | −0.05 | (0.60) | |||||

| 4. Physical functioning | 3.38 (0.602) | 3 (1–4) | −0.46 ** | −0.26 * | 0.23 * | (0.78) | ||||

| 5. Role functioning | 3.20 (0.98) | 3 (1–4) | −0.42 ** | −0.23 * | 0.08 | 0.63 ** | (0.87) | |||

| 6. Emotional functioning | 3.13 (0.69) | 3 (1–4) | −0.48 ** | −0.32 ** | 0.33 * | 0.40 ** | 0.44 ** | (0.86) | ||

| 7. Cognitive functioning | 3.54 (0.66) | 3 (1–4) | −0.29 ** | −0.49 ** | 0.10 | 0.44 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.62 ** | (0.60) | |

| 8. Social functioning | 3.13 (0.95) | 3 (1–4) | −0.41 ** | −0.46 ** | 0.10 | 0.34 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.58 ** | 0.46 ** | (0.80) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kiss, H.; Müller, V.; Dani, K.T.; Pikó, B.F. Health-Related Quality of Life, Illness Perception, Stigmatization and Optimism Among Hematology Patients: Two Exploratory Path Models. Medicina 2025, 61, 1704. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091704

Kiss H, Müller V, Dani KT, Pikó BF. Health-Related Quality of Life, Illness Perception, Stigmatization and Optimism Among Hematology Patients: Two Exploratory Path Models. Medicina. 2025; 61(9):1704. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091704

Chicago/Turabian StyleKiss, Hedvig, Vanessa Müller, Kristóf Tamás Dani, and Bettina Franciska Pikó. 2025. "Health-Related Quality of Life, Illness Perception, Stigmatization and Optimism Among Hematology Patients: Two Exploratory Path Models" Medicina 61, no. 9: 1704. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091704

APA StyleKiss, H., Müller, V., Dani, K. T., & Pikó, B. F. (2025). Health-Related Quality of Life, Illness Perception, Stigmatization and Optimism Among Hematology Patients: Two Exploratory Path Models. Medicina, 61(9), 1704. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091704