Risk of Diabetes-Specific Eating Disorders in Children with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Using Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion: A CGM-Based Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Grave, R.D. Eating Disorders: Progress and Challenges. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2011, 22, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetiner, E.B.; Donbaloğlu, Z.; Yüksel, A.I.; Singin, B.; Behram, B.A.; Bedel, A.; Parlak, M.; Tuhan, H. Disordered eating behaviors and associated factors in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Arch. Pédiatr. 2024, 31, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannucci, E.; Rotella, F.; Ricca, V.; Moretti, S.; Placidi, G.F.; Rotella, C.M. Eating disorders in patients with Type 1 diabetes: A meta-analysis. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2005, 28, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Jiang, H.; Lin, M.; Yu, S.; Wu, J. The impact of emotion regulation strategies on disordered eating behavior in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: A cross-sectional study. Front. Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1400997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, V.; Eiser, C.; Johnson, B.; Brierley, S.; Epton, T.; Elliott, J.; Heller, S. Eating problems in adolescents with Type 1 diabetes: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Diabet. Med. 2013, 30, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowitz, J.T.; Butler, D.A.; Volkening, L.K.; Antisdel, J.E.; Anderson, B.J.; Laffel, L.M.B. Brief Screening Tool for Disordered Eating in Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atik Altınok, Y.; Özgür, S.; Meseri, R.; Özen, S.; Darcan, Ş.; Gökşen, D. Reliability and Validity of the Diabetes Eating Problem Survey in Turkish Children and Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2017, 9, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biester, T.; Berget, C.; Boughton, C.; Cudizio, L.; Ekhlaspour, L.; Hilliard, M.E.; Reddy, L.; Um, S.S.N.; Schoelwer, M.; Sherr, J.L.; et al. International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2024: Diabetes Technologies—Insulin Delivery. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2024, 97, 636–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunger-Dathe, W.; Braun, A.; Müller, U.; Schiel, R.; Femerling, M.; Risse, A. Insulin Pump Therapy in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: Results of the Nationwide Quality Circle in Germany (ASD) 1999–2000. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2003, 111, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.M.; Young-Hyman, D.; Fischer, S.; Markowitz, J.T.; Muir, A.B.; Laffel, L.M. Examination of Psychosocial and Physiological Risk for Bulimic Symptoms in Youth with Type 1 Diabetes Transitioning to an Insulin Pump: A Pilot Study. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2018, 43, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priesterroth, L.; Grammes, J.; Clauter, M.; Kubiak, T. Diabetes technologies in people with type 1 diabetes mellitus and disordered eating: A systematic review on continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion, continuous glucose monitoring and automated insulin delivery. Diabet. Med. 2021, 38, e14581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atik-Altınok, Y.; Eliuz-Tipici, B.; İdiz, C.; Özgür, S.; Ok, A.M.; Karşıdağ, K. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the diabetes eatıng problem survey- revised (DEPS-R) among adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Eat. Weight. Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2023, 28, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, M.R.; Alemzadeh, R.; Katte, H.; Hall, P.L.; Perlmuter, L.C. Brief Report: Disordered Eating and Psychosocial Factors in Adolescent Females with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2006, 31, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, E.A.; Quinn, S.M.; Ambrosino, J.M.; Weyman, K.; Tamborlane, W.V.; Jastreboff, A.M. Disordered Eating Behaviors in Emerging Adults With Type 1 Diabetes: A Common Problem for Both Men and Women. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2017, 31, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, C.M.; Smart, C.E.; Fatima, A.; King, B.R.; Lopez, P. Increased bolus overrides and lower time in range: Insights into disordered eating revealed by insulin pump metrics and continuous glucose monitor data in Australian adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2024, 38, 108904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinz, N.; Bächle, C.; Becker, M.; Berger, G.; Galler, A.; Haberland, H.; Meusers, M.; Mirza, J.; Plener, P.L.; von Sengbusch, S.; et al. Insulin Pumps in Type 1 Diabetes with Mental Disorders: Real-Life Clinical Data Indicate Discrepancies to Recommendations. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2016, 18, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarçın, G.; Akman, H.; Güneş Kaya, D.; Serdengeçti, N.; İncetahtacı, S.; Turan, H.; Doğangün, B.; Ercan, O. Diabetes-specific eating disorder and possible associated psychopathologies in adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Eat. Weight. Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2023, 28, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tse, J.; Nansel, T.R.; Haynie, D.L.; Mehta, S.N.; Laffel, L.M.B. Disordered Eating Behaviors Are Associated with Poorer Diet Quality in Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 1810–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinhas-Hamiel, O.; Graph-Barel, C.; Boyko, V.; Tzadok, M.; Lerner-Geva, L.; Reichman, B. Long-Term Insulin Pump Treatment in Girls with Type 1 Diabetes and Eating Disorders—Is It Feasible? Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2010, 12, 873–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinehr, T.; Dieris, B.; Galler, A.; Teufel, M.; Berger, G.; Stachow, R.; Golembowski, S.; Ohlenschlager, U.; Holder, M.; Hummel, M.; et al. Worse Metabolic Control and Dynamics of Weight Status in Adolescent Girls Point to Eating Disorders in the First Years after Manifestation of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: Findings from the Diabetes Patienten Verlaufsdokumentation Registry. J. Pediatr. 2019, 207, 205–212.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, J.T.; Alleyn, C.A.; Phillips, R.; Muir, A.; Young-Hyman, D.; Laffel, L.M.B. Disordered Eating Behaviors in Youth with Type 1 Diabetes: Prospective Pilot Assessment Following Initiation of Insulin Pump Therapy. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2013, 15, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, N.Y.; Hashim, M.A.; Abdeen, M.S.E. Disordered eating behaviour in adolescents with type 1 diabetes on continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion; relation to body image, depression and glycemic control. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ercolino, G.T.; Sprinkles, J.; Fruik, A.; Muthukkumar, R.; Gopisetty, N.; Qu, X.; Young, L.A.; Mayer-Davis, E.J.; Sarteau, A.C.; Kahkoska, A.R. Disordered eating attitudes and behaviours among older adults with type 1 diabetes: An exploratory study. Diabet. Med. 2024, 42, e15504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niemelä, P.E.; Leppänen, H.A.; Voutilainen, A.; Möykkynen, E.M.; Virtanen, K.A.; Ruusunen, A.A.; Rintamäki, R.M. Prevalence of eating disorder symptoms in people with insulin-dependent-diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eat. Behav. 2024, 53, 101863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Embaye, J.; Hennekes, M.; Snoek, F.; De Wit, M. Psychometric properties of the Diabetes Eating Problem Survey–Revised among Dutch adults with type 1 diabetes and implications for clinical use. Diabet. Med. 2024, 41, e15313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisting, L.; Wonderlich, J.; Skrivarhaug, T.; Dahl-Jørgensen, K.; Rø, Ø. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the diabetes eating problem survey—revised (DEPS-R) among adult males and females with type 1 diabetes. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahia, S.; Salem, N.A.; Tobar, S.; Abdelmoneim, Z.; Mahmoud, A.M.; Laimon, W. Shedding light on eating disorders in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: Insights and implications. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2025, 184, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colman, M.H.E.; Quick, V.M.; Lipsky, L.M.; Dempster, K.W.; Liu, A.; Laffel, L.M.; Mehta, S.N.; Nansel, T.R. Disordered Eating Behaviors Are Not Increased by an Intervention to Improve Diet Quality but Are Associated with Poorer Glycemic Control Among Youth with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, S.R.; Zaremba, N.; Harrison, A.; Choudhary, P.; Cheah, Y.; Allan, J.; Debong, F.; Reid, F.; Treasure, J.; Hopkins, D.; et al. Disordered eating in women with type 1 diabetes: Continuous glucose monitoring reveals the complex interactions of glycaemia, self-care behaviour and emotion. Diabet. Med. 2021, 38, e14446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All | CSII (n:20) | MDI (n:44) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 13.32 ± 3.03 | 13.14 ± 3.67 | 13.42 ± 2.69 | 0.732 |

| Female% (n) | 56.3 (36) | 65 (13) | 52.2 (23) | 0.341 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 3.08 (1.85–5.02) | 3.94 (2.92–5.13) | 2.95 (1.36–4.85) | 0.075 |

| Age at presentation (years) | 9.90 (6.68–11.90) | 9.05 (5.38–11.07) | 10.5 (8.25–12.05) | 0.094 |

| Weight SDS | 0.29 ± 1.00 | 0.27 ± 1.12 | 0.30 ± 0.94 | 0.918 |

| Height SDS | 0.14 ± 0.89 | −0.01 ± 1.13 | 0.01 ± 0.77 | 0.994 |

| BMI | 20.84 ± 3.72 | 20.37 ± 3.75 | 21.07 ± 3.73 | 0.493 |

| BMI SDS | 0.31 ± 1.03 | 0.28 ± 1.12 | 0.32 ± 1.00 | 0.883 |

| HbA1c % | 7.15 (6.57–8.22) | 7.00 (6.42–7.87) | 7.3 (6.60–8.57) | 0.163 |

| DEPS-R score | 11 (7–17.75) | 14 (7.5–20.5) | 11 (6–17) | 0.302 |

| DEPS-R score ≥ 20 n (%) | 15 (23.4) | 6 (30) | 9 (20.4) | 0.403 |

| All | CSII | MDI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c < 7% (n:25) | 9 (4–15) | 14 (4–15.5) | 9 (4–17) | 0.565 |

| HbA1c 7–9% (n:29) | 11 (8–19) | 11 (8–24.5) | 10. 5 (7–17.5) | 0.408 |

| HbA1c > 9% (n:9) | 19 (12–32.5) | 16 (9–28) | 43.5 (40–43.5) | 0.036 * |

| DEPS-R < 20 | DEPS-R ≥ 20 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSII (n:14) | MDI (n:35) | p Value | CSII (n:6) | MDI (n:9) | p Value | |

| Female/male | 9/5 | 16/19 | 0.24 | 4/2 | 7/2 | 0.634 |

| Age | 13.01 ± 2.72 | 13.31 ± 2.69 | 0.733 | 13.82 ± 5.13 | 13.97 ± 2.83 | 0.140 |

| Age at presentation | 9.00 (5.75–10.62) | 10.36 (8.06–12.05) | 0.150 | 9.45 (4.37–13.40) | 11.25 (8.00–12.10) | 0.728 |

| Diabetes duration | 3.66 (2.67–4.85) | 3.00 (1.40–4.80) | 0.280 | 4.19 (3.01–7.12) | 2.10 (1.20–5.00) | 0.203 |

| BMI SDS | −0.05 ± 1.16 | 0.24 ± 1.00 | 0.385 | 0.99 ± 0.72 | 0.75 ± 0.96 | 0.256 |

| HbA1c | 6.70 (6.15–7.15) | 7.20 (6.60–8.30) | 0.041 * | 7.60 (6.47–9.17) | 8.90 (7.10–9.80) | 0.354 |

| Variable | Pearson’s r | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.185 | 0.146 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | −0.112 | 0.387 |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | 0.301 | 0.017 * |

| Weight SDS | 0.278 | 0.029 * |

| BMI | 0.329 | 0.009 * |

| BMI SDS | 0.356 | 0.004 * |

| HbA1c (%) | 0.403 | 0.001 * |

| Mean glucose | 0.470 | 0.003 * |

| GMI | 0.471 | 0.003 * |

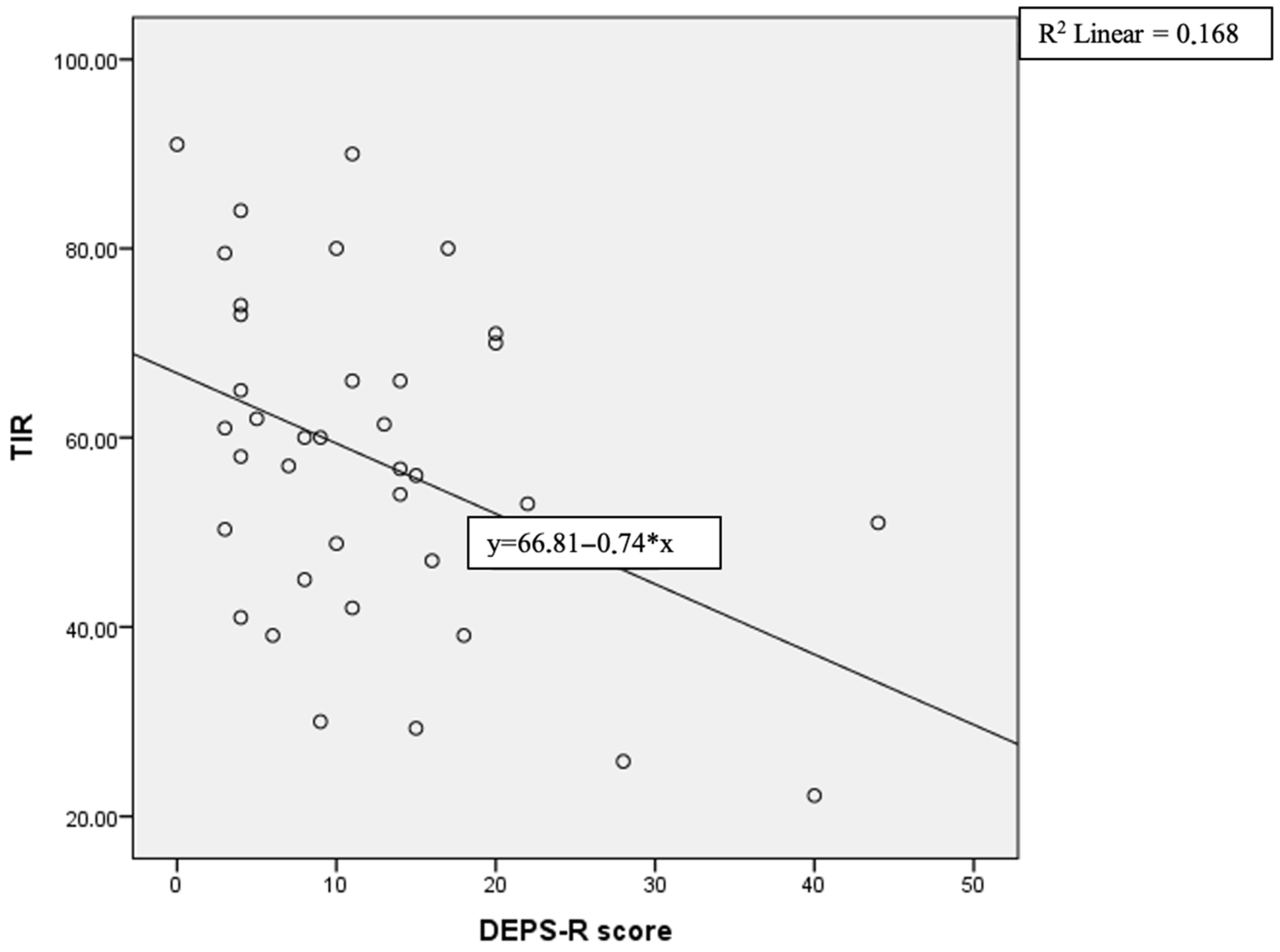

| TIR (%) | −0.0410 | 0.012 * |

| TING (%) | −0.669 | 0.1 |

| TAR (high, %) | −0.129 | 0.442 |

| TAR (very high, %) | 0.508 | 0.001 * |

| TBR (low, %) | 0.202 | 0.224 |

| TBR (very low, %) | −0.064 | 0.706 |

| Glucose SD (mg/dL) | −0.200 | 0.747 |

| CV | 0.417 | 0.010 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Köprülü, Ö.; Tan, H.; Erbaş, İ.M.; Şimşek, F.Y.; Uyar, N.; Karataş, M.Ç.; Nalbantoğlu, Ö.; Korkmaz, H.A.; Özkan, B. Risk of Diabetes-Specific Eating Disorders in Children with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Using Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion: A CGM-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Medicina 2025, 61, 1585. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091585

Köprülü Ö, Tan H, Erbaş İM, Şimşek FY, Uyar N, Karataş MÇ, Nalbantoğlu Ö, Korkmaz HA, Özkan B. Risk of Diabetes-Specific Eating Disorders in Children with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Using Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion: A CGM-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Medicina. 2025; 61(9):1585. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091585

Chicago/Turabian StyleKöprülü, Özge, Hülya Tan, İbrahim Mert Erbaş, Fatma Yavuzyılmaz Şimşek, Nilüfer Uyar, Murat Çağlar Karataş, Özlem Nalbantoğlu, Hüseyin Anıl Korkmaz, and Behzat Özkan. 2025. "Risk of Diabetes-Specific Eating Disorders in Children with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Using Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion: A CGM-Based Cross-Sectional Study" Medicina 61, no. 9: 1585. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091585

APA StyleKöprülü, Ö., Tan, H., Erbaş, İ. M., Şimşek, F. Y., Uyar, N., Karataş, M. Ç., Nalbantoğlu, Ö., Korkmaz, H. A., & Özkan, B. (2025). Risk of Diabetes-Specific Eating Disorders in Children with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Using Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion: A CGM-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Medicina, 61(9), 1585. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091585