Association Between Current Suicidal Ideation and Personality Traits: Analysis of the Personality Inventory for DSM-5 in a Community Mental Health Sample

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Psychometric Measures

2.1.1. Personality Inventory for DSM-5 (PID-5)

2.1.2. Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse (CECA.Q)

2.1.3. Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale—24 Items (BPRS-24)

2.1.4. Dissociative Experience Scale II (DES-II)

2.1.5. Clinical Global Impression—Severity (CGI-S)

2.1.6. Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised (ECR-R)

2.1.7. General Assessment of Functioning (GAF)

2.1.8. Statistical Analysis

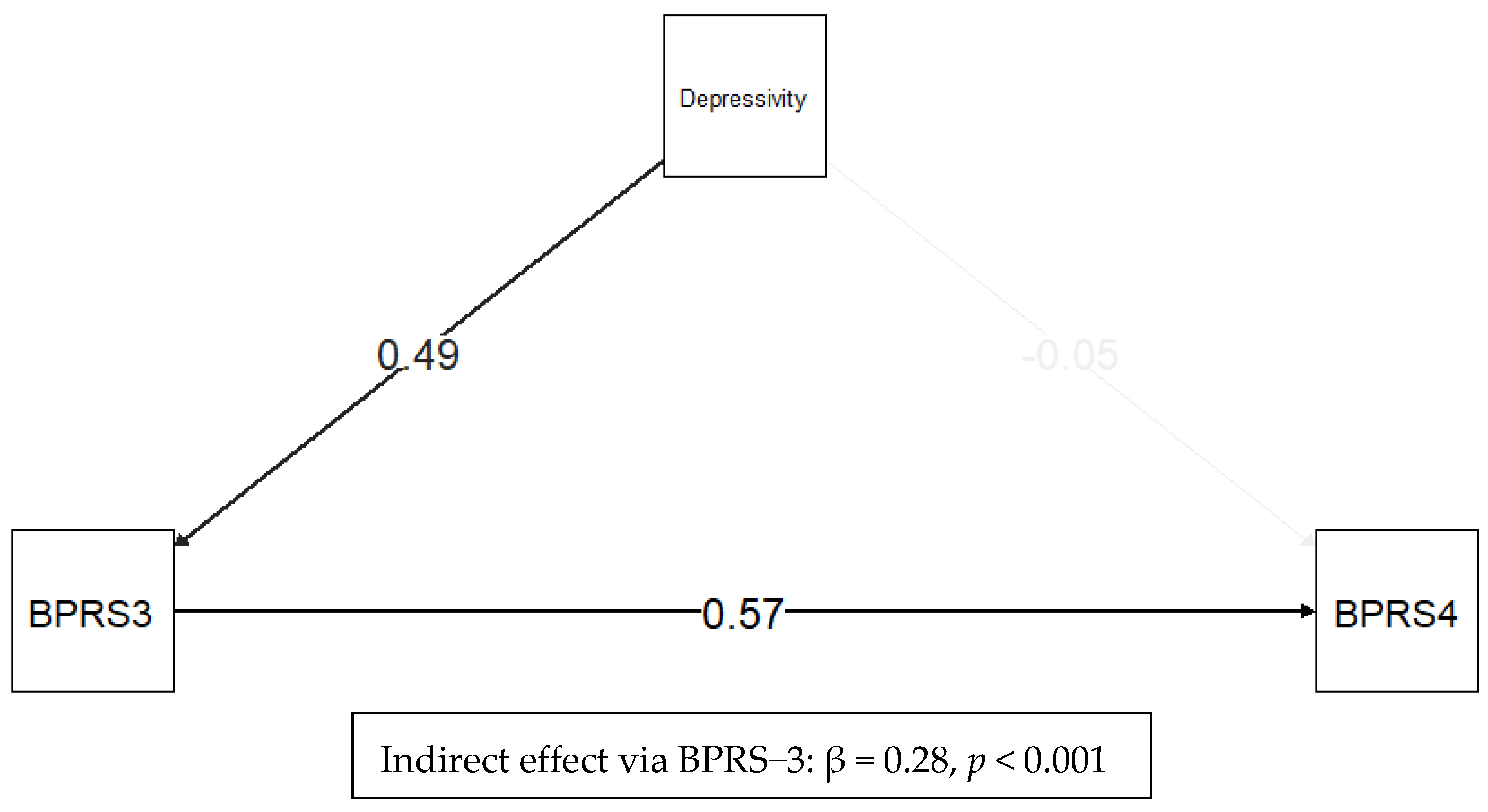

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Future Directions

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Term | Description |

| AMPD | Alternative Model for Personality Disorders | DSM-5 dimensional model for personality disorders, operationalized via the PID-5. |

| BPRS 3 | Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale—Item 3 (Depression) | Clinician-rated measure of depressive mood severity. |

| BPRS 4 | Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale—Item 4 (Suicidality) | Clinician-rated measure of suicidal ideation and related behaviors. |

| CES D | Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale | Self-report scale for depressive symptom severity. |

| CECA.Q | Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse Questionnaire | Structured self-report for assessing early-life trauma and neglect. |

| CGI | Clinical Global Impression | Clinician-rated global measure of illness severity. |

| DES II | Dissociative Experiences Scale, Version II | Self-report questionnaire for dissociative symptoms. |

| DSM 5 | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition | Psychiatric diagnostic manual by the American Psychiatric Association. |

| ERC R | Experiences in Close Relationships—Revised | Self-report scale for adult attachment styles. |

| NSSI | Non-Suicidal Self-Injury | Self-inflicted harm without intent to die. |

| PID 5 | Personality Inventory for DSM-5 | Self-report instrument for maladaptive personality traits. |

| SCID II/SCID IV | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (Axis II/DSM IV) | Semi-structured clinical interview for diagnosing personality disorders according to the DSM-IV. |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling | Statistical modeling framework for testing complex relationships among variables. |

References

- Fazel, S.; Runeson, B. Suicide. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilic, M.; Ilic, I. Worldwide Suicide Mortality Trends (2000–2019): A Joinpoint Regression Analysis. World J. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 1044–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moutier, C.Y.; Pisani, A.R.; Stahl, S.M. Suicide Prevention: Stahl’s Handbooks; Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology Handbooks; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-108-46362-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gariepy, G.; Zahan, R.; Osgood, N.D.; Yeoh, B.; Graham, E.; Orpana, H. Dynamic Simulation Models of Suicide and Suicide-Related Behaviors: Systematic Review. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2024, 10, e63195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.S.; Nguyen, B.L.; Lyons, B.H.; Sheats, K.J.; Wilson, R.F.; Betz, C.J.; Fowler, K.A. Surveillance for Violent Deaths—National Violent Death Reporting System, 48 States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, 2020. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2023, 72, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Bi, K.; Yip, P.S.-F.; Cerel, J.; Brown, T.T.; Peng, Y.; Pathak, J.; Mann, J.J. Decoding Suicide Decedent Profiles and Signs of Suicidal Intent Using Latent Class Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2024, 81, e240171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, A. Detection of Suicidal Patients: An Example of Some Limitations in the Prediction of Infrequent Events. J. Consult. Psychol. 1954, 18, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, K.R.; Huang, X.; Guzmán, E.M.; Funsch, K.M.; Cha, C.B.; Ribeiro, J.D.; Franklin, J.C. Interventions for Suicide and Self-Injury: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials across Nearly 50 Years of Research. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 146, 1117–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstra, E.; van Nieuwenhuizen, C.; Bakker, M.; Özgül, D.; Elfeddali, I.; de Jong, S.J.; van der Feltz-Cornelis, C.M. Effectiveness of Suicide Prevention Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2020, 63, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooding, P.; Pratt, D.; Edwards, D.; Awenat, Y.; Drake, R.J.; Emsley, R.; Jones, S.; Kapur, N.; Lobban, F.; Peters, S.; et al. Underlying Mechanisms and Efficacy of a Suicide-Focused Psychological Intervention for Psychosis, the Cognitive Approaches to Combatting Suicidality (CARMS): A Multicentre, Assessor-Masked, Randomised Controlled Trial in the UK. Lancet Psychiatry 2025, 12, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Lu, L.; Qian, Y.; Jin, X.-H.; Yu, H.-R.; Du, L.; Fu, X.-L.; Zhu, B.; Chen, H.-L. The Significance of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy on Suicide: An Umbrella Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 317, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calati, R.; Bensassi, I.; Courtet, P. The Link between Dissociation and Both Suicide Attempts and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: Meta-Analyses. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 251, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Mota, M.S.S.; Ulguim, H.B.; Jansen, K.; Cardoso, T.D.A.; Souza, L.D.D.M. Are Big Five Personality Traits Associated to Suicidal Behaviour in Adolescents? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 347, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, G.H.; Gonda, X.; Lolich, M.; Tondo, L.; Baldessarini, R.J. Suicidal Risk and Affective Temperaments, Evaluated with the TEMPS-A Scale: A Systematic Review. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2018, 26, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miola, A.; Baldessarini, R.J.; Pinna, M.; Tondo, L. Relationships of Affective Temperament Ratings to Diagnosis and Morbidity Measures in Major Affective Disorders. Eur. Psychiatry 2021, 64, e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deiana, V.; Suprani, F.; Paribello, P.; Mura, A.; Arzedi, C.; Garzilli, M.; Arru, L.; Manchia, M.; Carpiniello, B.; Pinna, F. Experience of Childhood Adversity and Maladaptive Personality Traits: Magnitude and Specificity of the Association in a Clinical Sample of Adult Outpatients. Pers. Ment. Health 2025, 19, e1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bifulco, A.; Bernazzani, O.; Moran, P.M.; Jacobs, C. The Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse Questionnaire (CECA.Q): Validation in a Community Series. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 44, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morosini, P.L.; Casacchia, M. Traduzione Italiana dellaBrief Psychiatric Rating Scale, Versionc 4.0 Anipliata(BPRS 4.0). Riv. Riabil. Psichiatr. Psicosoc. 1995, 4, 199–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri, M.; Koeter, M.; Schene, A.; Bonetto, C.; Vàzquez-Barquero, J.L.; Becker, T.; Knapp, M.; Knudsen, H.C.; Tansella, M.; Thornicroft, G. Factor Solution of the BPRS-Expanded Version in Schizophrenic Outpatients Living in Five European Countries. Schizophr. Res. 2005, 75, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingemans, P.M.; Linszen, D.H.; Lenior, M.E.; Smeets, R.M. Component Structure of the Expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS-E). Psychopharmacology 1995, 122, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafkenscheid, A. Psychometric Evaluation of a Standardized and Expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1991, 84, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roncone, R.; Ventura, J.; Impallomeni, M.; Falloon, I.R.; Morosini, P.L.; Chiaravalle, E.; Casacchia, M. Reliability of an Italian Standardized and Expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS 4.0) in Raters with High vs. Low Clinical Experience. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1999, 100, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzoumanian, M.A.; Verbeck, E.G.; Estrellado, J.E.; Thompson, K.J.; Dahlin, K.; Hennrich, E.J.; Stevens, J.M.; Dalenberg, C.J. Trauma Research Institute Psychometrics of Three Dissociation Scales: Reliability and Validity Data on the DESR, DES-II, and DESC. J. Trauma Dissociation 2023, 24, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saggino, A.; Molinengo, G.; Rogier, G.; Garofalo, C.; Loera, B.; Tommasi, M.; Velotti, P. Improving the Psychometric Properties of the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES-II): A Rasch Validation Study. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busner, J.; Targum, S.D. The Clinical Global Impressions Scale. Psychiatry 2007, 4, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fraley, R.C.; Waller, N.G.; Brennan, K.A. An Item Response Theory Analysis of Self-Report Measures of Adult Attachment. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 78, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moos, R.H.; Nichol, A.C.; Moos, B.S. Global Assessment of Functioning Ratings and the Allocation and Outcomes of Mental Health Services. Psychiatr. Serv. 2002, 53, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders|Psychiatry Online. Available online: https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787 (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R; RStudio, PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- JASP, Version 0.19.3; JASP (Version 0.19.3) [Computer software]; JASP Team: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. Available online: http://jasp-stats.org (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Wright, A.G.C.; Calabrese, W.R.; Rudick, M.M.; Yam, W.H.; Zelazny, K.; Williams, T.F.; Rotterman, J.H.; Simms, L.J. Stability of the DSM-5 Section III Pathological Personality Traits and Their Longitudinal Associations with Psychosocial Functioning in Personality Disordered Individuals. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2015, 124, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, B.; Liu, W.; Zhou, D.; Fu, X.; Qin, X.; Wu, J. Personality Traits and Suicide Attempts with and without Psychiatric Disorders: Analysis of Impulsivity and Neuroticism. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boot, K.; Wiebenga, J.X.M.; Eikelenboom, M.; van Oppen, P.; Thomaes, K.; van Marle, H.J.F.; Heering, H.D. Associations between Personality Traits and Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempts in Patients with Personality Disorders. Compr. Psychiatry 2022, 112, 152284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Salve, F.; Placenti, C.; Tagliabue, S.; Rossi, C.; Malvini, L.; Percudani, M.; Oasi, O. Are PID-5 Personality Traits and Self-Harm Attitudes Related? A Study on a Young Adult Sample Pre-Post COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2023, 11, 100475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, B.; Pires, R.; Henriques-Calado, J.; Sousa-Ferreira, A.; Gonçalves, B.; Pires, R.; Henriques-Calado, J.; Sousa-Ferreira, A. Evaluation of the PID-5 Depressivity Personality Dimensions and Depressive Symptomatology in a Community Sample. An. De Psicol. 2022, 38, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somma, A.; Fossati, A.; Terrinoni, A.; Williams, R.; Ardizzone, I.; Fantini, F.; Borroni, S.; Krueger, R.F.; Markon, K.E.; Ferrara, M. Reliability and Clinical Usefulness of the Personality Inventory for DSM-5 in Clinically Referred Adolescents: A Preliminary Report in a Sample of Italian Inpatients. Compr. Psychiatry 2016, 70, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moselli, M.; Casini, M.P.; Frattini, C.; Williams, R. Suicidality and Personality Pathology in Adolescence: A Systematic Review. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2023, 54, 290–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboul-Ata, M.A.; Qonsua, F.T.; Saadi, I.A.A. Personality Pathology and Suicide Risk: Examining the Relationship Between DSM-5 Alternative Model Traits and Suicidal Ideation and Behavior in College-Aged Individuals. Psychol. Rep. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudinova, A.Y.; MacPherson, H.A.; Musella, K.; Schettini, E.; Gilbert, A.C.; Jenkins, G.A.; Clark, L.A.; Dickstein, D.P. Maladaptive Personality Traits and the Course of Suicidal Ideation in Young Adults with Bipolar Disorder: Cross Sectional and Prospective Approaches. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2021, 51, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loas, G.; Solibieda, A.; Rotsaert, M.; Englert, Y. Suicidal Ideations among Medical Students: The Role of Anhedonia and Type D Personality. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, B.; Fjeldsted, R. The Role of DSM-5 Borderline Personality Symptomatology and Traits in the Link between Childhood Trauma and Suicidal Risk in Psychiatric Patients. Borderline Pers. Disord. Emot. Dysregul. 2017, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, B.D.L.; Galea, S.; Wood, E.; Kerr, T. Longitudinal Associations Between Types of Childhood Trauma and Suicidal Behavior Among Substance Users: A Cohort Study. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, e69–e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.B.; Esposito-Smythers, C.; Weismoore, J.T.; Renshaw, K.D. The Relation Between Child Maltreatment and Adolescent Suicidal Behavior: A Systematic Review and Critical Examination of the Literature. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 16, 146–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioletti, A.; Bornstein, R. Do PID-5 Trait Scores Predict Symptom Disorders? A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Personal. Disord. 2024, 38, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riera-Serra, P.; Navarra-Ventura, G.; Castro, A.; Gili, M.; Salazar-Cedillo, A.; Ricci-Cabello, I.; Roldán-Espínola, L.; Coronado-Simsic, V.; García-Toro, M.; Gómez-Juanes, R.; et al. Clinical Predictors of Suicidal Ideation, Suicide Attempts and Suicide Death in Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2024, 274, 1543–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.; Morgan, T.A.; Stanton, K. The Severity of Psychiatric Disorders. World Psychiatry 2018, 17, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonda, X.; Fountoulakis, K.N.; Kaprinis, G.; Rihmer, Z. Prediction and Prevention of Suicide in Patients with Unipolar Depression and Anxiety. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2007, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotov, R.; Krueger, R.F.; Watson, D.; Achenbach, T.M.; Althoff, R.R.; Bagby, R.M.; Brown, T.A.; Carpenter, W.T.; Caspi, A.; Clark, L.A.; et al. The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): A Dimensional Alternative to Traditional Nosologies. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2017, 126, 454–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengartner, M.P.; von Wyl, A.; Heiniger Haldimann, B.; Yamanaka-Altenstein, M. Personality Traits and Psychopathology Over the Course of Six Months of Outpatient Psychotherapy: A Prospective Observational Study. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.L.L.; Kim, H.L.; Romain, A.-M.N.; Tabani, S.; Chaplin, W.F. Personality Change and Personality as Predictor of Change in Psychotherapy: A Longitudinal Study in a Community Mental Health Clinic. J. Res. Personal. 2020, 87, 103980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldessarini, R.J.; Tondo, L. Testing for Antisuicidal Effects of Lithium Treatment. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, E.L.; Bossarte, R.M.; Dobscha, S.K.; Gildea, S.M.; Hwang, I.; Kennedy, C.J.; Liu, H.; Luedtke, A.; Marx, B.P.; Nock, M.K.; et al. Estimated Average Treatment Effect of Psychiatric Hospitalization in Patients With Suicidal Behaviors: A Precision Treatment Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2024, 81, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorr, A.C.; Ammerman, B.A.; LaFleur, S.A.; Misra, D.; Dhruv, M.A.; Karunakaran, B.; Strony, R.J. An Investigation of Clinical Decisionmaking: Identifying Important Factors in Treatment Planning for Suicidal Patients in the Emergency Department. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2020, 1, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, L. Resilience as a Focus of Suicide Research and Prevention. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2019, 140, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigoni, A.; Delvecchio, G.; Turtulici, N.; Madonna, D.; Pietrini, P.; Cecchetti, L.; Brambilla, P. Machine Learning and the Prediction of Suicide in Psychiatric Populations: A Systematic Review. Transl. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholi Zadeh Kharrat, F.; Gagne, C.; Lesage, A.; Gariépy, G.; Pelletier, J.-F.; Brousseau-Paradis, C.; Rochette, L.; Pelletier, E.; Lévesque, P.; Mohammed, M.; et al. Explainable Artificial Intelligence Models for Predicting Risk of Suicide Using Health Administrative Data in Quebec. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melia, R.; Musacchio Schafer, K.; Rogers, M.L.; Wilson-Lemoine, E.; Joiner, T.E. The Application of AI to Ecological Momentary Assessment Data in Suicide Research: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e63192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Zhao, Q.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Tong, Y.; Fu, G. An Exploratory Deep Learning Approach for Predicting Subsequent Suicidal Acts in Chinese Psychological Support Hotlines. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.16463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.A.; Dill, D.L. Dissociative Symptoms in Relation to Childhood Physical and Sexual Abuse. Am. J. Psychiatry 1990, 147, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossati, A.; Borroni, S.; Somma, A.; Krueger, R.F.; Markon, K.E. PID-5 Manuale e Guida All’uso Clinico Della Versione Italiana; Cortina Editore: Milan, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, A.P.; Machado, G.M.; Pianowski, G.; De Francisco Carvalho, L. Using Pathological Traits for the Assessment of Suicide Risk: A Suicide Indicator Proposal for the Dimensional Clinical Personality Inventory 2. Rev. Colomb. De Psicol. 2022, 31, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipale, H.; Schneider-Thoma, J.; Pinzón-Espinosa, J.; Radua, J.; Efthimiou, O.; Vinkers, C.H.; Mittendorfer-Rutz, E.; Cardoner, N.; Pintor, L.; Tanskanen, A.; et al. Representation and Outcomes of Individuals With Schizophrenia Seen in Everyday Practice Who Are Ineligible for Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.J.; Waternaux, C.; Haas, G.L.; Malone, K.M. Toward a Clinical Model of Suicidal Behavior in Psychiatric Patients. AJP 1999, 156, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item 4—Suicide Risk |

|---|

| 1. Symptom Absent |

| Deny suicidal ideation |

| 2. Very Mild |

| Occasionally tired of living. No suicidal thoughts. |

| 3. Mild |

| Occasional suicidal thoughts that do not translate into a clear decision or plan, and/or the patient often has the impression that it would be better if they were dead. |

| 4. Moderate |

| Frequent suicidal thoughts without a concrete decision or established plans to end one’s life. |

| 5. Moderately Severe |

| The patient has many suicidal fantasies and thinks about different ways to end their life. They may also formulate precise plans or set a specific time to do so and/or have made an impulsive suicide attempt using a non-lethal method or knowing they could be saved. |

| 6. Severe |

| The patient clearly wants to end their life. They are actively seeking the right moment and means to do so and/or have carried out a serious suicide attempt, even if the method used did not completely rule out the possibility of being rescued. |

| 7. Very Severe |

| The patient has a clear intention and a well-defined suicide plan (e.g., “As soon as… I will end my life by doing…”) and/or has made a suicide attempt using a method they believed to be certainly lethal or that was inherently dangerous and carried out in an isolated location. |

| Reasons for Non-Eligibility | N | % of Total (n = 561) | Relative % Among Excluded (n = 424) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No longer in care | 260 | 46.3% | 61.3% |

| Cognitive impairment | 37 | 6.6% | 8.7% |

| Clinical severity (CGI-S > 4) | 18 | 3.2% | 4.2% |

| Unavailable | 105 | 18.7% | 24.8% |

| Language difficulties | 3 | 0.5% | 0.7% |

| Deceased | 1 | 0.2% | 0.2% |

| Subtotal | 424 | 75.6% | 100% |

| Included in the study | 137 | 24.4% | — |

| Variable (Median or %) | BPRS Suicide Risk ≤ 3 | BPRS Suicide Risk > 3 | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex assigned at birth female—n (%) | 75 (62.5) | 14 (82.3) | 0.108 |

| GAF | 60.0 | 55.0 | 0.163 |

| CGI | 4.0 | 4.0 | 0.219 |

| Years of observation | 2.7 | 3.6 | 0.705 |

| Age | 54.4 | 55.1 | 0.793 |

| Education—n (%) | 0.629 | ||

| Primary | 9 (7.5) | 2 (11.7) | |

| Secondary | 43 (35.8) | 3 (17.6) | |

| High school | 42 (35.0) | 8 (47.0) | |

| University | 26 (21.6) | 4 (23.5) | |

| Occupation—n (%) | 0.470 | ||

| Working | 55 (45.8) | 9 (52.9) | |

| Homemaker | 8 (6.6) | 2 (11.7) | |

| Student | 12 (10.0) | 2 (11.7) | |

| Retired | 7 (5.8) | 2 (11.7) | |

| Unemployed | 38 (31.6) | 2 (11.7) | |

| Age of onset—(years, mean) | 28.0 | 27.0 | 0.829 |

| CECA—mother antipathy | 16.0 | 22.0 | 0.117 |

| CECA—mother neglect | 15.5 | 19.0 | 0.023 |

| CECA—mother psychological abuse | 2.0 | 8.0 | 0.042 |

| CECA—father antipathy | 17.0 | 16.0 | 0.463 |

| CECA—father neglect | 19.0 | 20.0 | 0.243 |

| CECA—father psychological abuse | 2.0 | 4.0 | 0.200 |

| CECA—role inversion | 45.0 | 51.0 | 0.378 |

| PID-5 domains and validity scales | |||

| Negative affect | 1.2 | 1.4 | 0.395 |

| Detachment | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.104 |

| Antagonism | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.339 |

| Disinhibition | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.560 |

| Psychoticism | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.165 |

| ERC attachment styles | |||

| Anxious attachment | 65.0 | 65.0 | 0.837 |

| Avoidant attachment | 72.0 | 68.0 | 0.445 |

| Substance use disorder | 15 (12.5) | 1 (5.8) | 0.427 |

| Personality disorder (at least one) | 42 (35) | 11 (64.7) | 0.019 |

| BPRS-24 item 3: depression severity | 2 | 4 | <0.001 |

| Current mood disorder diagnosis | 54 (45) | 12 (70) | 0.049 |

| Mood stabilizer | 5 (62.5) | 94 (72.9) | 0.819 |

| Antidepressant | 3 (37.5) | 50 (38.8) | 1.000 |

| Typical antipsychotic | 8 (100) | 124 (96.1) | 1.000 |

| Atypical antipsychotic | 5 (62.5) | 99 (76.7) | 0.625 |

| Anxiolytic/hypnotic | 3 (37.5) | 62 (48.1) | 0.829 |

| Psychotherapy/rehabilitation | 4 (50.0) | 79 (61.2) | 0.796 |

| Individual psychotherapy | 4 (50.0) | 84 (65.1) | 0.627 |

| Group psychotherapy | 6 (75.0) | 120 (93.0) | 0.250 |

| Study/Year | Sample Type | Controlled for Depression Severity? | Depressivity—Suicidality Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| Somma et al. (2016) [36] | Adolescent inpatients | Mood diagnosis only | Significant (depressivity, anhedonia, submissiveness) |

| De Salve et al. (2023) [34] | Young adults (general + clinical) | No | Significant (negative affectivity, detachment) |

| Aboul-Ata et al. (2023) [38] | College-aged young adults | No | Significant (depressivity, detachment, psychoticism) |

| Gonçalves et al. (2022) [35] | Portuguese community adults | No | Not specifically addressing suicidality—found that depressivity and anhedonia were associated with CES-D depression severity |

| Bach & Fjeldsted (2017) [41] | In- and outpatient mental health services | No | Negative affectivity traits (incl. depressivity) mediate the trauma–suicidality link. Addressed potential circularity by excluding the three PID-5 items surrounding suicide, still finding a significant association |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deiana, V.; Paribello, P.; Suprani, F.; Mura, A.; Arzedi, C.; Garzilli, M.; Arru, L.; Manchia, M.; Carpiniello, B.; Pinna, F. Association Between Current Suicidal Ideation and Personality Traits: Analysis of the Personality Inventory for DSM-5 in a Community Mental Health Sample. Medicina 2025, 61, 1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091541

Deiana V, Paribello P, Suprani F, Mura A, Arzedi C, Garzilli M, Arru L, Manchia M, Carpiniello B, Pinna F. Association Between Current Suicidal Ideation and Personality Traits: Analysis of the Personality Inventory for DSM-5 in a Community Mental Health Sample. Medicina. 2025; 61(9):1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091541

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeiana, Valeria, Pasquale Paribello, Federico Suprani, Andrea Mura, Carlo Arzedi, Mario Garzilli, Laura Arru, Mirko Manchia, Bernardo Carpiniello, and Federica Pinna. 2025. "Association Between Current Suicidal Ideation and Personality Traits: Analysis of the Personality Inventory for DSM-5 in a Community Mental Health Sample" Medicina 61, no. 9: 1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091541

APA StyleDeiana, V., Paribello, P., Suprani, F., Mura, A., Arzedi, C., Garzilli, M., Arru, L., Manchia, M., Carpiniello, B., & Pinna, F. (2025). Association Between Current Suicidal Ideation and Personality Traits: Analysis of the Personality Inventory for DSM-5 in a Community Mental Health Sample. Medicina, 61(9), 1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091541