Impact of Medical Residency Programs on Emergency Department Efficiency

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

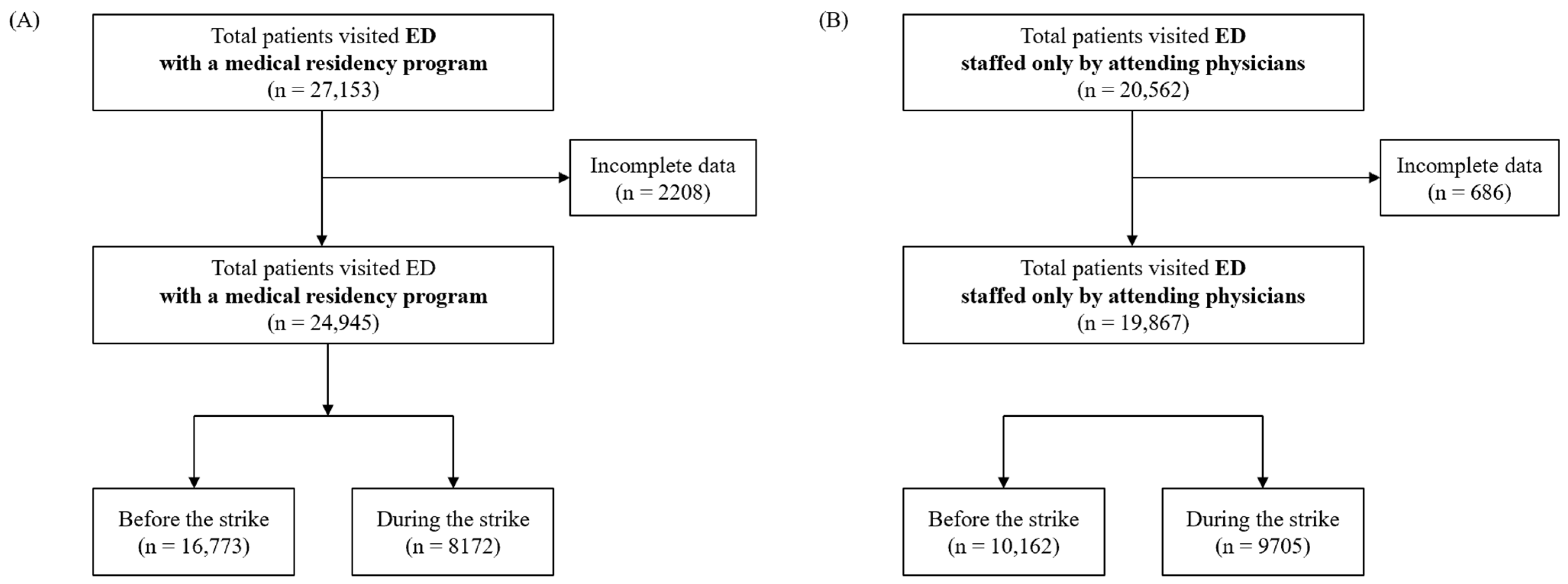

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Outcome Measurement

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. ED with a Medical Residency Program Versus ED Staffed Only by Attending Physicians Before the Strike

3.2. Before Versus During the Strike in the Two EDs

3.3. ED with a Medical Residency Program Versus ED Staffed Only by Attending Physicians During the Strike

3.4. Patients Who Were Admitted to the ICU

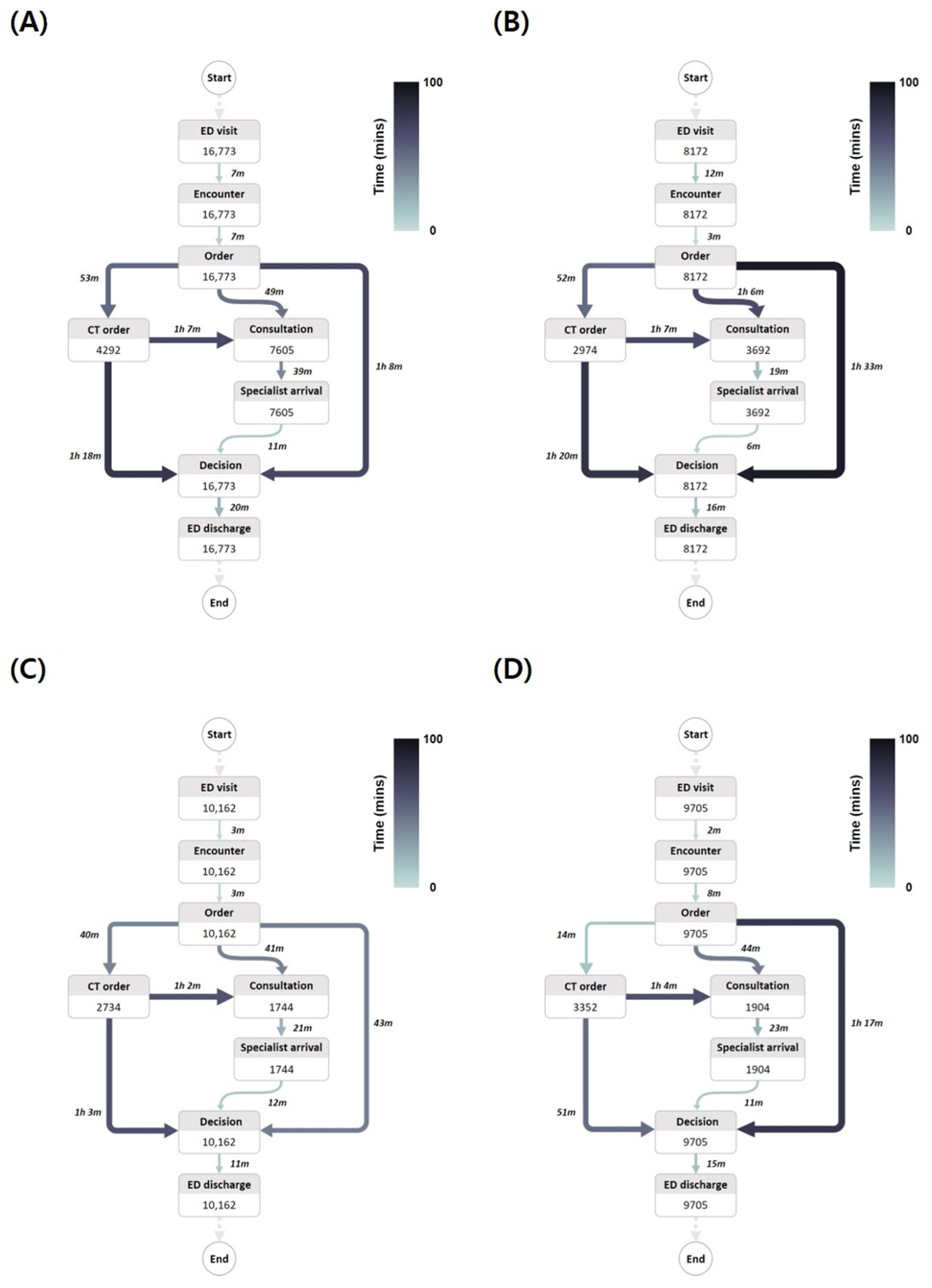

3.5. Clinical Flow in Both EDs Before and During Strike

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| ED with a Medical Residents | ED Staffed Only by Attending Physicians | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Before the Strike (n = 560) | During the Strike (n = 515) | p-Value | Before the Strike (n = 338) | During the Strike (n = 404) | p-Value |

| Door to first encounter (min) | 5.0 (2.0–9.0) | 10.0 (5.0–21.0) | <0.001 | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | <0.001 |

| Door to order (min) | 8.0 (3.0–13.0) | 9.0 (5.0–15.0) | <0.001 | 7.0 (3.0–12.0) | 8.0 (5.0–11.0) | 0.270 |

| CT order | 282 (50.4) | 213 (41.4) | 0.004 | 135 (39.9) | 203 (50.2) | 0.006 |

| Door to CT order (min) | 74.0 (27.0–111.0) | 60.0 (23.0–91.0) | 0.007 | 43.0 (15.0–86.5) | 35.0 (9.0–92.0) | 0.303 |

| Intubation | 108 (19.3) | 101 (19.6) | 0.954 | 27 (8.0) | 52 (12.9) | 0.043 |

| Door to intubation (min) | 60.0 (26.0–143.5) | 38.0 (19.0–154.0) | 0.118 | 52.0 (27.0–172.0) | 64.5 (28.5–165.0) | 0.984 |

| Central catheter insertion | 190 (33.9) | 158 (30.7) | 0.284 | 41 (12.1) | 56 (13.9) | 0.557 |

| Door to central catheter insertion (min) | 80.5 (37.0–203.0) | 138.0 (36.0–246.0) | 0.073 | 212.0 (98.0–363.0) | 223.0 (120.5–311.0) | 0.962 |

| Arterial catheter insertion | 360 (64.3) | 340 (66.0) | 0.595 | 119 (35.2) | 213 (52.7) | <0.001 |

| Door to arterial catheter insertion (min) | 98.0 (37.5–294.0) | 140.5 (29.0–309.5) | 0.922 | 218.0 (73.0–363.0) | 174.0 (70.0–316.0) | 0.282 |

| Door to decision (min) | 171.5 (83.0–280.0) | 117.0 (66.0–175.5) | <0.001 | 108.0 (64.0–176.0) | 100.0 (52.0–167.5) | 0.279 |

| ED length of stay (min) | 247.5 (151.5–351.5) | 175.0 (117.5–238.0) | <0.001 | 189.5 (123.0–257.0) | 157.0 (97.0–232.5) | 0.001 |

| Hospital length of stay (d) | 12.0 (5.0–31.0) | 12.0 (6.0–25.0) | 0.855 | 8.0 (4.0–16.0) | 10.0 (5.0–20.0) | 0.016 |

| In-hospital mortality | 85 (15.2) | 80 (15.5) | 0.939 | 27 (8.0) | 48 (11.9) | 0.103 |

References

- Young, S.C.; Oh, H.K.; Hee, J.; Chun, S.Y.; Sang, H.P.; Yeon, H.Y.; Tae, Y.S.; Gi, W.K. Survey of emergency medicine residency education programs and suggestion for improvement on the future emergency medicine residency education. J. Korean Soc. Emerg. Med. 2018, 29, 179–187. [Google Scholar]

- Stolley, P.D.; Becker, M.H.; Lasagna, L.; McEvilla, J.D.; Sloane, L.M. The relationship between physician characteristics and prescribing appropriateness. Med. Care 1972, 10, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ki, O.A.; Soon, Y.Y.; Sang, J.L.; Koo, Y.J.; Jun, H.C.; Heui, S.J. Definition and Analysis of Overcrowding in the Emergency Department of Ten Tertiary Hospitals. J. Korean Soc. Emerg. Med. 2004, 15, 261–272. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Z.; Zobel, C.W.; Khansa, L.; Glick, R.E. Emergency department resilience to disaster-level overcrowding: A component resilience framework for analysis and predictive modeling. J. Oper. Manag. 2020, 66, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, S.L.; Aronsky, D.; Duseja, R.; Epstein, S.; Handel, D.; Hwang, U.; McCarthy, M.; John McConnell, K.; Pines, J.M.; Rathlev, N.; et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on clinically oriented outcomes. Acad. Emerg. Med. Off. J. Soc. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2009, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, M.J.; Graham, C.A. Why emergency medicine needs senior decision makers. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2011, 18, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Günther, C.W.; van der Aalst, W.M. Fuzzy mining—Adaptive process simplification based on multi-perspective metrics. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Process Management, Brisbane, Australia, 24–28 September 2007; pp. 328–343. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, M.; Al Shaar, M.; Cave, G.; Wallace, M.; Brydon, P. Correlation of physician seniority with increased emergency department efficiency during a resident doctors’ strike. N. Z. Med. J. 2008, 121, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lammers, R.L.; Roiger, M.; Rice, L.; Overton, D.T.; Cucos, D. The effect of a new emergency medicine residency program on patient length of stay in a community hospital emergency department. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2003, 10, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, C.; Harper, M.; Johnston, P.; Sanders, B.; Shannon, M. Effect of trainees on length of stay in the pediatric emergency department. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2009, 16, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarry, J.; Krall, S.P.; McLaughlin, T. Impact of resident physicians on emergency department throughput. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2010, 11, 333–335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dehon, E.; McLemore, G.; McKenzie, L.K. Impact of trainees on length of stay in the emergency department at an Academic Medical Center. South. Med. J. 2015, 108, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farnan, J.M.; Johnson, J.K.; Meltzer, D.O.; Humphrey, H.J.; Arora, V.M. Resident uncertainty in clinical decision making and impact on patient care: A qualitative study. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2008, 17, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brick, C.; Lowes, J.; Lovstrom, L.; Kokotilo, A.; Villa-Roel, C.; Lee, P.; Lang, E.; Rowe, B.H. The impact of consultation on length of stay in tertiary care emergency departments. Emerg. Med. J. 2014, 31, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, P.; Steiner, I.; Reinhardt, G. Analysis of factors influencing length of stay in the emergency department. Can. J. Emerg. Med. 2003, 5, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.H.; Cho, J.W.; Ryoo, H.W.; Moon, S.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Jang, T.C.; Lee, D.E. Impact of an emergency department resident strike during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Daegu, South Korea: A retrospective cross-sectional study. J. Yeungnam Med. Sci. 2022, 39, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, J.; Choi, Y.; Jeong, J. Changes in Emergency Department Performance during Strike of Junior Physicians in Korea. Emerg. Med. Int. 2021, 2021, 1786728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravioli, S.; Jina, R.; Risk, O.; Cantle, F. Impact of junior doctor strikes on patient flow in the emergency department: A cross-sectional analysis. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 31, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, R.D.; Dib, S.; McLarty, D.; Shaikh, S.; Cheeti, R.; Zhou, Y.; Ghasemi, Y.; Rahman, M.; Schrader, C.D.; Wang, H. Productivity, efficiency, and overall performance comparisons between attendings working solo versus attendings working with residents staffing models in an emergency department: A Large-Scale Retrospective Observational Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, R.; Dubin, J.; Maloy, K. Impact of learners on emergency medicine attending physician productivity. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2014, 15, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | ED with a Medical Residency Program (n = 16,773) | ED Staffed Only by Attending Physicians (n = 10,162) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 53.0 (32.0–70.0) | 49.0 (35.0–65.0) | <0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 7298 (43.5) | 4191 (41.2) | <0.001 |

| Triage level | <0.001 | ||

| Levels 1 and 2 | 453 (2.7) | 597 (5.9) | |

| Levels 3 to 5 | 16,320 (97.3) | 9565 (94.1) | |

| Door to first encounter (min) | 7.0 (4.0–12.0) | 3.0 (1.0–5.0) | <0.001 |

| Door to order (min) | 15.0 (9.0–23.0) | 9.0 (5.0–13.0) | <0.001 |

| CT order | 4292 (25.6) | 2734 (26.9) | 0.018 |

| Door to CT order (min) | 73.5 (23.0–115.0) | 59.0 (15.0–98.0) | <0.001 |

| 1st consultation | 7605 (45.3) | 1744 (17.2) | <0.001 |

| Door to consultation (min) | 95.0 (42.0–146.0) | 72.0 (27.0–124.0) | <0.001 |

| Door to specialist arrival (min) | 156.0 (90.0–238.0) | 117.0 (63.0–176.0) | <0.001 |

| 2nd consultation | 668 (4.0) | 56 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Door to consultation (min) | 183.5 (126.0–251.5) | 148.5 (88.0–201.5) | 0.005 |

| Door to specialist arrival (min) | 283.0 (201.0–398.5) | 206.0 (143.5–335.0) | 0.004 |

| 3rd consultation | 59 (0.4) | 0 | |

| Door to consultation (min) | 202 (143.5–307.5) | 0 | |

| Door to specialist arrival (min) | 329 (228.0–510.5) | 0 | |

| 4th consultation | 11 (0.1) | 0 | |

| Door to consultation (min) | 298 (197–346.5) | 0 | |

| Door to specialist arrival (min) | 396 (370.5–490.0) | 0 | |

| Door to decision (min) | 134.0 (70.0–208.0) | 92.0 (32.0–139.0) | <0.001 |

| ED length of stay (min) | 165.0 (95.0–260.0) | 116.0 (49.0–174.0) | <0.001 |

| Disposition | <0.001 | ||

| Discharge | 10,410 (62.0) | 6405 (63.0) | |

| Admission to general ward | 3064 (18.3) | 1857 (18.3) | |

| Admission to ICU | 560 (3.3) | 338 (3.3) | |

| Transfer | 1947 (11.6) | 1492 (14.7) | |

| Death | 42 (0.2) | 21 (0.2) | |

| Against discharge | 750 (4.5) | 49 (0.5) |

| ED with a Medical Residency Program | ED Staffed Only by Attending Physicians | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Before the Strike (n = 16,773) | During the Strike (n = 8172) | p-Value | Before the Strike (n = 10,162) | During the Strike (n = 9705) | p-Value |

| Age (years) | 53.0 (32.0–70.0) | 60.0 (37.0–76.0) | <0.001 | 49.0 (35.0–65.0) | 53.0 (36.0–68.0) | <0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 7298 (43.5) | 3816 (46.7) | <0.001 | 4191 (41.2) | 4239 (43.7) | <0.001 |

| Triage level | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Levels 1 and 2 | 453 (2.7) | 506 (6.2) | 597 (5.9) | 884 (9.1) | ||

| Levels 3 to 5 | 16,320 (97.3) | 7666 (93.8) | 9565 (94.1) | 8821 (90.9) | ||

| Door to first encounter (min) | 7.0 (4.0–12.0) | 14.0 (8.0–26.0) | <0.001 | 3.0 (1.0–5.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | <0.001 |

| Door to order (min) | 15.0 (9.0–23.0) | 16.0 (10.0–25.0) | <0.001 | 9.0 (5.0–13.0) | 11.0 (7.0–15.0) | <0.001 |

| CT order | 4292 (25.6) | 2974 (36.4) | <0.001 | 2734 (26.9) | 3352 (34.5) | <0.001 |

| Door to CT order (min) | 73.5 (23.0–115.0) | 45.0 (18.0–96.0) | <0.001 | 59.0 (15.0–98.0) | 44.0 (13.0–98.0) | 0.001 |

| 1st consultation | 7605 (45.3) | 3692 (45.2) | <0.001 | 1744 (17.2) | 1904 (19.6) | <0.001 |

| Door to consultation (min) | 95.0 (42.0–146.0) | 102.0 (54.0–148.0) | <0.001 | 72.0 (27.0–124.0) | 70.0 (25.0–122.0) | 0.237 |

| Door to specialist arrival (min) | 156.0 (90.0–238.0) | 132.0 (84.0–185.0) | <0.001 | 117.0 (63.0–176.0) | 118.0 (66.0–179.0) | 0.591 |

| Door to decision (min) | 134.0 (70.0–208.0) | 134.0 (90.0–188.0) | 0.011 | 92.0 (32.0–139.0) | 108.0 (64.0–151.0) | <0.001 |

| ED length of stay (min) | 165.0 (95.0–260.0) | 162.0 (114.0–224.0) | 0.364 | 116.0 (49.0–174.0) | 133.0 (90.0–191.0) | <0.001 |

| Disposition | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Discharge | 10,410 (62.0) | 5316 (65.0) | 6405 (63.0) | 7005 (72.2) | ||

| Admission to general ward | 3064 (18.3) | 2055 (25.1) | 1857 (18.3) | 2130 (21.9) | ||

| Admission to ICU | 560 (3.3) | 515 (6.3) | 338 (3.3) | 404 (4.2) | ||

| Transfer | 1947 (11.6) | 118 (1.4) | 1492 (14.7) | 91 (0.9) | ||

| Death | 42 (0.2) | 25 (0.3) | 21 (0.2) | 27 (0.3) | ||

| Against discharge | 750 (4.5) | 143 (1.7) | 49 (0.5) | 48 (0.5) | ||

| Variable | ED with a Medical Residency Program (n = 8172) | ED Staffed Only by Attending Physicians (n = 9705) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60.0 (37.0–76.0) | 53.0 (36.0–68.0) | <0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 3816 (46.7) | 4239 (43.7) | <0.001 |

| Triage level | <0.001 | ||

| Levels 1 and 2 | 506 (6.2) | 884 (9.1) | |

| Levels 3 to 5 | 7666 (93.8) | 8821 (90.9) | |

| Door to first encounter (min) | 14.0 (8.0–26.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | <0.001 |

| Door to order (min) | 16.0 (10.0–25.0) | 11.0 (7.0–15.0) | <0.001 |

| CT order | 2974 (36.4) | 3352 (34.5) | 0.01 |

| Door to CT order (min) | 45.0 (18.0–96.0) | 44.0 (13.0–98.0) | <0.001 |

| 1st consultation | 3692 (45.2) | 1904 (19.6) | <0.001 |

| Door to consultation (min) | 102.0 (54.0–148.0) | 70.0 (25.0–122.0) | <0.001 |

| Door to specialist arrival (min) | 132.0 (84.0–185.0) | 118.0 (66.0–179.0) | <0.001 |

| Door to decision (min) | 134.0 (90.0–188.0) | 108.0 (64.0–151.0) | <0.001 |

| ED length of stay (min) | 162.0 (114.0–224.0) | 133.0 (90.0–191.0) | <0.001 |

| Disposition | <0.001 | ||

| Discharge | 5316 (65.0) | 7005 (72.2) | |

| Admission to general ward | 2055 (25.1) | 2130 (21.9) | |

| Admission to ICU | 515 (6.3) | 404 (4.2) | |

| Transfer | 118 (1.4) | 91 (0.9) | |

| Death | 25 (0.3) | 27 (0.3) | |

| Against discharge | 143 (1.7) | 48 (0.5) |

| Before the Strike | During the Strike | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | ED with a Medical Residency Program (n = 560) | ED Staffed Only by Attending Physicians (n = 338) | p-Value | ED with a Medical Residency Program (n = 515) | ED Staffed Only by Attending Physicians (n = 404) | p-Value |

| Door to first encounter (min) | 5.0 (2.0–9.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | <0.001 | 10.0 (5.0–21.0) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | <0.001 |

| Door to order (min) | 8.0 (3.0–13.0) | 7.0 (3.0–12.0) | 0.146 | 9.0 (5.0–15.0) | 8.0 (5.0–11.0) | <0.001 |

| CT order | 282 (50.4) | 135 (39.9) | 0.003 | 213 (41.4) | 203 (50.2) | 0.009 |

| Door to CT order (min) | 74.0 (27.0–111.0) | 43.0 (15.0–86.5) | <0.001 | 60.0 (23.0–91.0) | 35.0 (9.0–92.0) | 0.003 |

| Intubation | 108 (19.3) | 27 (8.0) | <0.001 | 101 (19.6) | 52 (12.9) | 0.008 |

| Door to intubation (min) | 60.0 (26.0–143.5) | 52.0 (27.0–172.0) | 0.867 | 38.0 (19.0–154.0) | 64.5 (28.5–165.0) | 0.189 |

| Central catheter insertion | 190 (33.9) | 41 (12.1) | <0.001 | 158 (30.7) | 56 (13.9) | <0.001 |

| Door to central catheter insertion (min) | 80.5 (37.0–203.0) | 212.0 (98.0–363.0) | <0.001 | 138.0 (36.0–246.0) | 223.0 (120.5–311.0) | 0.001 |

| Arterial catheter insertion | 360 (64.3) | 119 (35.2) | <0.001 | 340 (66.0) | 213 (52.0) | <0.001 |

| Door to arterial catheter insertion (min) | 98.0 (37.5–294.0) | 218.0 (73.0–363.0) | 0.001 | 140.5 (29.0–309.5) | 174.0 (70.0–316.0) | 0.014 |

| Door to decision (min) | 171.5 (83.0–280.0) | 108.0 (64.0–176.0) | <0.001 | 117.0 (66.0–175.5) | 100.0 (52.0–167.5) | 0.011 |

| ED length of stay (min) | 247.5 (151.5–351.5) | 189.5 (123.0–257.0) | <0.001 | 175.0 (117.5–238.0) | 157.0 (97.0–232.5) | 0.014 |

| Hospital length of stay (d) | 12.0 (5.0–31.0) | 8.0 (4.0–16.0) | <0.001 | 12.0 (6.0–25.0) | 10.0 (5.0–20.0) | 0.003 |

| In-hospital mortality | 85 (15.2) | 27 (8.0) | 0.002 | 80 (15.5) | 48 (11.9) | 0.136 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Namgung, M.; Bae, S.J.; Chung, H.S.; Jung, K.Y.; Choi, Y.H.; Kim, C.W.; Gong, Y.L.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, D.-H. Impact of Medical Residency Programs on Emergency Department Efficiency. Medicina 2025, 61, 999. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61060999

Namgung M, Bae SJ, Chung HS, Jung KY, Choi YH, Kim CW, Gong YL, Lee JY, Lee D-H. Impact of Medical Residency Programs on Emergency Department Efficiency. Medicina. 2025; 61(6):999. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61060999

Chicago/Turabian StyleNamgung, Myeong, Sung Jin Bae, Ho Sub Chung, Kwang Yul Jung, Yun Hyung Choi, Chan Woong Kim, Ye Lim Gong, Ji Yun Lee, and Dong-Hoon Lee. 2025. "Impact of Medical Residency Programs on Emergency Department Efficiency" Medicina 61, no. 6: 999. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61060999

APA StyleNamgung, M., Bae, S. J., Chung, H. S., Jung, K. Y., Choi, Y. H., Kim, C. W., Gong, Y. L., Lee, J. Y., & Lee, D.-H. (2025). Impact of Medical Residency Programs on Emergency Department Efficiency. Medicina, 61(6), 999. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61060999