Measuring Quality of Life in Stroke Survivors: Validity and Reliability of the Spanish COOP/WONCA Scale

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Measurements and Data Collection

2.2.1. Health-Related Quality of Life

2.2.2. Socio-Demographic and Clinical Data Form

2.2.3. Motor Impairment

2.2.4. Functional Measurements

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Participants

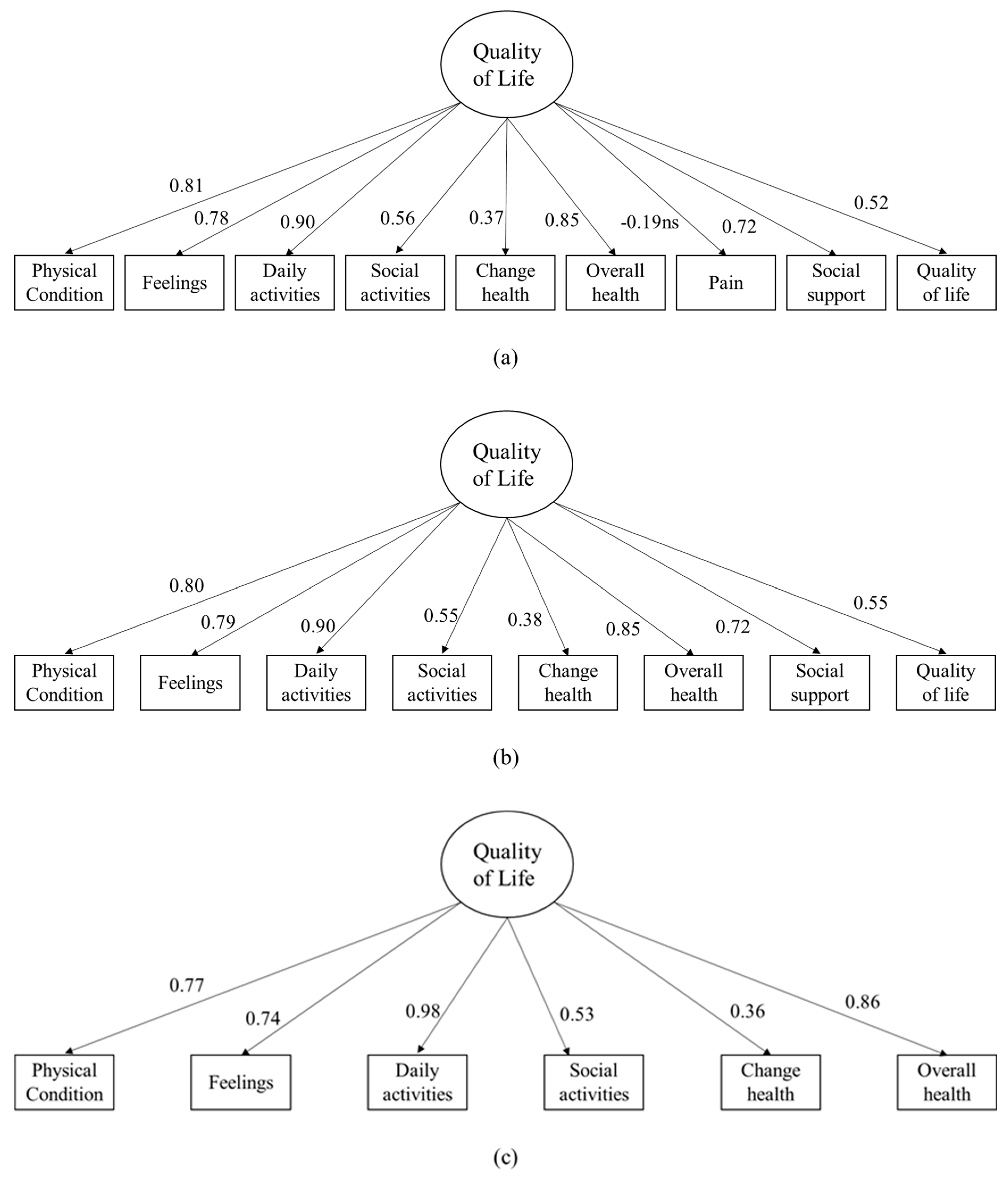

3.2. Dimensionality

3.3. Reliability

3.4. Criterion-Related and Differential Validity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crocker, T.F.; Brown, L.; Lam, N.; Wray, F.; Knapp, P.; Forster, A. Information provision for stroke survivors and their carers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 11, CD001919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shi, Z.; Bai, R.; Zheng, J.; Ma, S.; Wei, J.; Liu, G.; Wang, Y. Temporal, geographical and demographic trends of stroke prevalence in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveau, C.M.; Riancho, J.; Shaman, J.; Santurtún, A. Spatial analysis of ischemic stroke in Spain: The roles of accessibility to healthcare and economic development. Cad. Saúde Pública 2024, 40, e00212923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koleck, M.; Gana, K.; Lucot, C.; Darrigrand, B.; Mazaux, J.-M.; Glize, B. Quality of Life in Aphasic Patients 1 Year After a First Stroke. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 26, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Buono, V.; Corallo, F.; Bramanti, P.; Marino, S. Coping strategies and health-related quality of life after stroke. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, T.; Yusoff, S.Z.B.; Churilov, L.; Ma, H.; Davis, S.; Donnan, G.A.; Carey, L.M. Increased work and social engagement is associated with increased stroke specific quality of life in stroke survivors at 3 months and 12 months post-stroke: A longitudinal study of an Australian stroke cohort. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2017, 24, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geyh, S.; Cieza, A.; Kollerits, B.; Grimby, G.; Stucki, G. Content comparison of health-related quality of life measures used in stroke based on the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF): A systematic review. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 833–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Moriche, N.; Rodríguez-Gonzalo, A.; Muñoz-Lobo, M.J.; Parra-Cordero, S.; Pablos, A.F.-D. Calidad de vida en pacientes con ictus. Un estudio fenomonológico. Enfermería Clínica 2010, 20, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, B.P.; Flores, T.R.; Mielke, G.I.; Thumé, E.; Facchini, L.A. Multimorbidity and mortality in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016, 67, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, T.F.; Brown, L.; Clegg, A.; Farley, K.; Franklin, M.; Simpkins, S.; Young, J. Quality of life is substantially worse for community-dwelling older people living with frailty: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual. Life Res. 2019, 28, 2041–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Weel, C. Measuring Functional Health Status with the COOP/WONCA Charts: A Manual; Noordelijke Centrum voor Gezondheidsvraagstukken: Groningen, The Netherlands, 1995; 51p. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, L.J.; Wales, K.; Casey, A.; Pike, S.; Jolliffe, L.; Schneider, E.J.; Christie, L.J.; Ratcliffe, J.; Lannin, N.A. Self-reported quality of life following stroke: A systematic review of instruments with a focus on their psychometric properties. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 31, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donkor, E.S. Stroke in the 21st Century: A Snapshot of the burden, epidemiology, and quality of life. Stroke Res. Treat. 2018, 2018, 3238165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.N.; Mesa, R.A.; Kiladjian, J.; Al-Ali, H.; Gisslinger, H.; Knoops, L.; Squier, M.; Sirulnik, A.; Mendelson, E.; Zhou, X.; et al. Health-related quality of life and symptoms in patients with myelofibrosis treated with ruxolitinib versus best available therapy. Br. J. Haematol. 2013, 162, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widar, M.; Ahlström, G.; Ek, A. Health-related quality of life in persons with long-term pain after a stroke. J. Clin. Nurs. 2004, 13, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López Liria, R.; Vega Ramírez, F.A.; Rodríguez Martín, C.R.; Padilla Góngora, D.; Martínez Cortés, M.d.C.; Lucas Acién, F. Actualizaciones en las escalas de medida para la calidad de vida y funcionalidad del paciente con accidente cerebrovascular. INFAD Rev. Psicol. 2011, 4, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Badia, X. Qué es y cómo se mide la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud. Gastroenterol. Y Hepatol. 2003, 27 (Suppl. S3), 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudela, L.; Reig Ferrer, A. Adaptación transcultural de una medida de la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud: La versión española de las viñetas COOP/WONCA. Atención Primaria 1998, 24, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Solis Cartas, U.; Hernández Cuéllar, I.M.; Prada Hernández, D.M.; de Armas Hernández, A. Evaluation of the functional capacity in patient with osteoarthritis. Rev. Cuba. Reumatol 2014, 16, 23–29. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1817-59962014000100004&lng=es (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Martín-Díaz, F.; Reig-Ferrer, A.; Ferrer-Cascales, R. Sexual functioning and quality of life of male patients on hemodialysis. Soc. Española Nefrol. 2006, 26, 452–460. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, F.; López-Gómez, J.M.; Pérez-García, R. Clinicopathologic correlations of renal pathology in Spain. Kidney Int. 2004, 66, 898–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frostegård, J. Immunity, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoudi, H.; Jafari, P.; Ghaffaripour, S. Validation of the Persian version of COOP/WONCA functional health status charts in liver transplant candidates. Prog. Transplant. 2014, 24, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andres, E.; Temme, M.; Raderschatt, B.; Szecsenyi, J.; Sandholzer, H.; Kochen, M.M. COOP-WONCA charts: A suitable functional status screening instrument in acute low back pain? Br. J. Gen. Pract. 1995, 45, 661–664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Møller, T.; Gudde, C.B.; Folden, G.E.; Linaker, O.M. The experience of caring in relatives to patients with serious mental illness: Gender differences, health and functioning. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2009, 23, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Azevedo-Marques, J.M.; Zuardi, A.W. COOP/WONCA charts as a screen for mental disorders in primary care. Ann. Fam. Med. 2011, 9, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essink-Bot, M.-L.; Krabbe, P.F.M.; Bonsel, G.J.; Aaronson, N.K. An empirical comparison of four generic health status measures. Med. Care 1997, 35, 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoopman, R.; Terwee, C.B.; Muller, M.J.; Öry, F.G.; Aaronson, N.K. Methodological challenges in quality of life research among Turkish and Moroccan ethnic minority cancer patients: Translation, recruitment and ethical issues. Ethn. Health 2008, 14, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettema, A.M.; An, K.-N.; Zhao, C.; O’Byrne, M.M.; Amadio, P.C. Flexor tendon and synovial gliding during simultaneous and single digit flexion in idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome. J. Biomech. 2008, 41, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghipour, M.; Salavati, M.; Nabavi, S.M.; Akhbari, B.; Takamjani, I.E.; Negahban, H.; Rajabzadeh, F. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Persian version of COOP/WONCA charts in Persian-speaking Iranians with multiple sclerosis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 40, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappalardo, A.; Chisari, C.G.; Montanari, E.; Pesci, I.; Borriello, G.; Pozzilli, C.; D’Amico, E.; Patti, F. The clinical value of Coop/Wonca charts in assessment of HRQoL in a large cohort of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients: Results of a multicenter study. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2017, 17, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, O.C.; Carey, A.; Creed, A.; Durcan, S.; Blake, C. Reliability and validity of COOP/WONCA Functional Health Status Charts for stroke patients in primary care. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2010, 20, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Baalen, B.; Odding, E.; Van Woensel, M.P.; Van Kessel, M.A.; Roebroeck, M.E.; Stam, H.J. Reliability and sensitivity to change of measurement instruments used in a traumatic brain injury population. Clin. Rehabil. 2006, 20, 686–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenciana, G.; Neurology Department, Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe. Hospital La Fe Conciencia Sobre la Importancia de la Prevención del Ictus. Available online: https://lafe.san.gva.es/es/-/l-hospital-la-fe-consciencia-sobre-la-import%C3%A0ncia-de-la-prevenci%C3%B3-del-ictus (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Vilagut, G.; Ferrer, M.; Rajmil, L.; Rebollo, P.; Permanyer-Miralda, G.; Quintana, J.M.; Santed, R.; Valderas, J.M.; Ribera, A.; Domingo-Salvany, A.; et al. El Cuestionario de Salud SF-36 español: Una década de experiencia y nuevos desarrollos. Gac. Sanit. 2005, 19, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudela, L.L.; Ferrer, A.R. La evaluación de la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en la consulta: Las viñetas COOP/WONCA. Atención Primaria 2002, 29, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, A.; Saz, P.; Marcos, G.; Día, J.L.; De La Cámara, C.; Ventura, T.; Asín, F.M.; Pascual, L.F.; Montañés, J.Á.; Aznar, S. Revalidation and standardization of the cognition mini-exam (first Spanish version of the Mini-Mental Status Examination) in the general geriatric population. PubMed 1999, 112, 767–774. [Google Scholar]

- De Carvalho, R.M.F.; Mazzer, N.; Barbieri, C.H. Análise da confiabilidade e reprodutibilidade da goniometria em relação à fotogrametria na mão. Acta Ortopédica Bras. 2012, 20, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathiowetz, V.; Weber, K.; Volland, G.; Kashman, N. Reliability and validity of grip and pinch strength evaluations. J. Hand Surg. 1984, 9, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peolsson, A.; Hedlundm, R.; Oberg, B. Intra- and inter-tester reliability and reference values for hand strength. J. Rehabil. Med. 2001, 33, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, R.W.; Smith, M.B. Interrater reliability of a modified Ashworth scale of muscle spasticity. Phys. Ther. 1987, 67, 206–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregson, J.M.; Leathley, M.; Moore, A.P.; Sharma, A.K.; Smith, T.L.; Watkins, C.L. Reliability of the tone assessment scale and the modified ashworth scale as clinical tools for assessing poststroke spasticity. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1999, 80, 1013–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuyens, G.; De Weerdt, W.; Ketelaer, P.; Feys, H.; De Wolf, L.; Hantson, L.; Nieuwboer, A.; Spaepen, A.; Carton, H. Inter-rater reliability of the Ashworth scale in multiple sclerosis. Clin. Rehabil. 1994, 8, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiowetz, V.; Volland, G.; Kashman, N.; Weber, K. Adult norms for the box and block test of manual dexterity. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1985, 39, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baztán, J.; Pérez del Molino, J.; Alarcón, T.; San Cristóbal, E.; Izquierdo, G.; Manzarbeitia, J. Índice de Barthel: Instrumento válido para la valoración funcional de pacientes con enfermedad cerebrovascular. Rev. Española Geriatría Y Gerontolología 1993, 28, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Finney, S.J.; DiStefano, C. Nonnormal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course, 2nd ed.; Hancock, G.R., Mueller, O., Eds.; IAP Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2013; pp. 439–492. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthen, L.K.; Muthen, B.O. MPlus Version 8 User’s Guide; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Piñol Jané, A.; Sanz Carrillo, C. Importancia de la evaluación de la calidad de vida en atención primaria. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004, 27 (Suppl. S3), 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Concepción, O.; Román-Pastoriza, Y.; Álvarez-González, M.A.; Verdecia-Fraga, R.; Ramírez-Pérez, E.; Martínez-González-Quevedo, J.; Buergo-Zuaznábar, M.A. Desarrollo de una escala para evaluar la calidad de vida en los supervivientes a un ictus. Rev. Nuerología 2004, 39, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Nakao, M.; Obata, H.; Ikeda, H.; Kanda, T.; Wang, Q.; Hara, Y.; Omori, H.; Ishihara, Y. Application of the COOP/WONCA charts to aged patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A comparison between Japanese and Chinese populations. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrero-Pérez, E.J.; Díaz-Olalla, J.M. COOP/WONCA: Fiabilidad y validez de la prueba administrada telefónicamente. Atención Primaria 2015, 48, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, M.D.; Alvarez-Ude, F.; Reig-Ferrer, A.; Zito, J.P.; Gil, M.T.; Carretón, M.A.; Albiach, B.; Moledous, A. Emotional distress and health-related quality of life in patients on hemodialysis: The clinical value of COOP-WONCA charts. PubMed 2007, 20, 304–310. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, E.; Alonso, B.; Fernández, M.J.; Fernández, J.M.; Flórez, M.; García-Montes, I.; Gentil, J.; Hernández, L.; Juan, F.J.; Palomino, B.; et al. Rehabilitación del ictus: Modelo asistencial. Recomendaciones de la Sociedad Española de Rehabilitación y Medicina Física. Rehabilitación 2010, 44, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 55 (60.4) |

| Female | 36 (39.6) | |

| Ictus type | Hemorrhagic | 27 (30) |

| Ischemic | 63 (70) | |

| Hemiparesis | Right | 38 (41.8) |

| Left | 53 (58.2) | |

| Pain | Yes | 52 (57.1) |

| No | 39 (42.9) | |

| Aphasia | Yes | 9 (9.9) |

| No | 82 (90.1) | |

| Shoulder motor control | Yes | 55 (60.4) |

| No | 36 (39.6) |

| Variables | Mean ± DT | Minimum–Maximum |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 68.84 ± 9.44 | 44–93 |

| BMI | 26.16 ± 3.22 | 20.70–36.52 |

| Time post-stroke (months) | 23.60 ± 41.39 | 1–216 |

| MMSE | 28.64 ± 4.15 | 19–35 |

| Barthel Index | 66.04 ± 20.24 | 30–100 |

| Box and Block Test | 7.58 ± 8.84 | 0–31 |

| Grip strength | 6.57 ± 6.77 | 0–24 |

| Variables | Mean ± DT |

|---|---|

| Physical form | 1.68 ± 1.584 |

| Feelings | 1.26 ± 1.291 |

| Daily activities | 1.10 ± 1.266 |

| Social activity | 1.20 ± 1.457 |

| Change in health | 1.66 ± 1.423 |

| General health | 1.90 ± 1.799 |

| Pain | 1.22 ± 1.542 |

| Social support | 1.20 ± 1.212 |

| Quality of life | 1.44 ± 1.327 |

| Physical Condition | Feelings | Daily Activities | Social Activity | Health Change | Health Status | Pain | Social Support | Quality of Life | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | p | 0.192 | 0.005 ** | 0.044 * | 0.503 | 0.019 * | 0.146 | 0.694 | 0.206 | 0.132 |

| Male | 2.44 (0.89) | 2.53 (1.18) | 2.22 (1.18) | 2.27 (0.67) | 3.20 (0.75) | 2.15 (1.26) | 1.75 (0.77) | 2.35 (0.67) | ||

| Female | 3.06 (1.14) | 3.00 (1.09) | 2.36 (1.15) | 2.64 (0.76) | 3.44 (0.80) | 2.25 (1.29) | 1.97 (0.91) | 2.50 (0.69) | ||

| Ictus type | p | 0.211 | 0.431 | 0.615 | 0.815 | 0.308 | 0.339 | 0.205 | 0.876 | 0.333 |

| Hemorrhagic | 2.56 (0.89) | 2.67 (1.33) | 2.22 (1.15) | 2.52 (0.97) | 3.41 (0.84) | 1.96 (0.94) | 1.81 (0.87) | 2.52 (0.80) | ||

| Ischaemic | 2.75 (1.10) | 2.76 (1.08) | 2.29 (1.18) | 2.37 (0.60) | 3.29 (0.70) | 2.29 (1.39) | 1.83 (0.81) | 2.37 (0.63) | ||

| Hemiparesis | p | 0.286 | 0.558 | 0.174 | 0.004 ** | 0.003 ** | 0.376 | 0.004 ** | 0.181 | 0.009 ** |

| Right | 2.61 (0.88) | 2.89 (1.15) | 2.68 (1.23) | 2.21 (0.77) | 3.21 (0.77) | 1.76 (0.99) | 1.97 (0.91) | 2.21 (0.52) | ||

| Left | 2.74 (1.14) | 2.58 (1.16) | 1.98 (1.02) | 2.57 (0.66) | 3.36 (0.78) | 2.49 (1.36) | 1.74 (0.76) | 2.55 (0.74) | ||

| Pain | p | 0.533 | 0.260 | 0.607 | 0.098 | 0.126 | 0.673 | 0.000 ** | 0.150 | 0.304 |

| Yes | 2.79 (0.99) | 2.77 (1.07) | 2.42 (1.14) | 2.52 (0.77) | 3.33 (0.73) | 2.92 (1.04) | 1.73 (0.81) | 2.46 (0.72) | ||

| No | 2.54 (1.09) | 2.64 (1.28) | 2.08 (1.17) | 2.28 (0.64) | 3.26 (0.85) | 1.21 (0.80) | 1.97 (0.84) | 2.33 (0.62) | ||

| Shoulder motor control | p | 0.044 * | 0.064 | 0.053 | 0.041 * | 0.029 * | 0.328 | 0.052 | 0.065 | 0.319 |

| Yes | 2.53 (1.03) | 2.53 (1.13) | 2.11 (1.21) | 2.55 (0.53) | 3.27 (0.75) | 2.38 (1.40) | 1.71 (0.80) | 2.36 (0.70) | ||

| No | 2.92 (1.02) | 3.00 (1.17) | 2.53 (1.05) | 2.22 (0.92) | 3.33 (0.82) | 1.89 (0.97) | 2.03 (0.84) | 2.47 (0.65) |

| Physical Condition | Feelings | Daily Activities | Social Activity | Health Change | Health Status | Pain | Social Support | QoL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.254 * | 0.113 | 0.214 * | 0.148 | −0.162 | 0.293 ** | 0.137 | 0.173 | 0.126 |

| BMI | 0.062 | −0.314 ** | −0.139 | −0.100 | 0.222 * | −0.012 | −0.122 | −0.004 | 0.063 |

| Time post-stroke (months) | −0.340 ** | −0.296 ** | −0.457 ** | −0.188 | 0.322 ** | −0.342 ** | −0.202 | 0.087 | 0.001 |

| MMSE | −0.351 ** | −0.178 | −0.333 ** | −0.288 ** | 0.490 ** | −0.266 * | 0.063 | −0.290 ** | −0.073 |

| Barthel Index | 0.629 ** | −0.174 | 0.627 ** | −0.389 ** | 0.300 ** | −0.339 ** | 0.073 | −0.261 * | −0.240 * |

| Box and Block Test | −0.261 * | −0.276 ** | −0.110 | −0.069 | 0.149 | 0.095 | 0.163 | −0.312 ** | −0.165 |

| Wrist resting angle | 0.218 * | 0.165 | 0.190 | −0.163 | 0.097 | 0.201 | 0.172 | −0.156 | 0.023 |

| Wrist active extension | −0.088 | −0.173 | 0.091 | 0.053 | 0.133 | 0.192 | 0.087 | −0.268 * | −0.123 |

| Wrist passive extension | −0.077 | −0.178 | 0.130 | 0.096 | 0.058 | 0.121 | −0.172 | −0.338 ** | −0.084 |

| MCP resting angle | 0.109 | 0.083 | 0.182 | 0.195 | 0.077 | 0.336 ** | 0.154 | −0.128 | 0.262 * |

| MCP active extension | −0.070 | −0.151 | 0.243 * | 0.033 | −0.299 ** | −0.139 | −0.137 | −0.258 * | −0.109 |

| Grip strength | −0.158 | −0.284 ** | −0.213 * | 0.075 | 0.140 | 0.207 | −0.198 | −0.132 | −0.260 * |

| Pinch strength | −0.215 * | −0.401 ** | −0.160 | 0.078 | 0.264 * | 0.017 | −0.054 | −0.213 * | −0.250 * |

| MAS score for elbow flexors | 0.015 | 0.164 | −0.035 | 0.120 | −0.172 | −0.210 * | 0.022 | 0.113 | 0.031 |

| MAS score for wrist flexors | 0.105 | 0.122 | 0.207 * | 0.311 ** | −0.302 ** | −0.100 | 0.002 | 0.065 | −0.042 |

| MAS score for MCP flexors | −0.005 | 0.148 | −0.057 | 0.053 | −0.262 * | −0.166 | 0.078 | 0.017 | −0.017 |

| MAS score for IP flexors | −0.049 | 0.207 * | −0.066 | 0.063 | −0.175 | −0.146 | 0.141 | 0.067 | 0.056 |

| Physical Condition | Feelings | Daily Activities | Social Activity | Health Change | Health Status | Pain | Social Support | QoL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF Physical functioning | −0.502 ** | 0.134 | −0.449 * | −0.256 | 0.010 | −0.430 * | −0.200 | −0.195 | −0.349 |

| SF Role—physical | −0.259 | −0.154 | −0.415 * | −0.312 | −0.240 | −0.173 | −0.059 | −0.170 | −0.346 |

| SF Mental health | −0.056 | −0.220 | 0.032 | −0.402 * | −0.057 | −0.472 ** | −0.240 | −0.110 | −0.505 ** |

| SF Role—emotional | −0.188 | −0.472 ** | −0.161 | −0.130 | −0.347 | 0.005 | 0.030 | −0.280 | −0.279 |

| SF Social functioning | −0.287 | −0.042 | −0.122 | −0.656 ** | −0.159 | −0.540 ** | −0.243 | −0.213 | −0.495 ** |

| SF Vitality | −0.490 ** | 0.149 | −0.206 | −0.472 ** | −0.041 | −0.753 ** | −0.254 | −0.219 | −0.514 ** |

| SF General health | −0.530 ** | 0.094 | 0.102 | −0.422 * | −0.048 | −0.804 ** | −0.334 | −0.117 | −0.620 ** |

| SF Bodily pain | −0.090 | −0.018 | −0.167 | −0.361 | −0.121 | −0.406 * | −0.779 ** | −0.215 | −0.403 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sentandreu-Mañó, T.; García-Mollá, A.; Oltra Ferrús, I.; Tomás, J.M.; Salom Terrádez, J.R. Measuring Quality of Life in Stroke Survivors: Validity and Reliability of the Spanish COOP/WONCA Scale. Medicina 2025, 61, 878. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050878

Sentandreu-Mañó T, García-Mollá A, Oltra Ferrús I, Tomás JM, Salom Terrádez JR. Measuring Quality of Life in Stroke Survivors: Validity and Reliability of the Spanish COOP/WONCA Scale. Medicina. 2025; 61(5):878. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050878

Chicago/Turabian StyleSentandreu-Mañó, Trinidad, Adrián García-Mollá, Inmaculada Oltra Ferrús, José M. Tomás, and José Ricardo Salom Terrádez. 2025. "Measuring Quality of Life in Stroke Survivors: Validity and Reliability of the Spanish COOP/WONCA Scale" Medicina 61, no. 5: 878. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050878

APA StyleSentandreu-Mañó, T., García-Mollá, A., Oltra Ferrús, I., Tomás, J. M., & Salom Terrádez, J. R. (2025). Measuring Quality of Life in Stroke Survivors: Validity and Reliability of the Spanish COOP/WONCA Scale. Medicina, 61(5), 878. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050878