Targeting Ovarian Neoplasms: Subtypes and Therapeutic Options

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. OC—Histological Subtypes and Genetic Alterations

2.1. OC—Histological Subtypes

| Tumor Types (WHO 2020 Classification) | Associated with | Biomarkers for Diagnosis | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Epithelial 1.1. Serous Serous cystadenoma, adenofibroma and surface papilloma Serous borderline tumor Low-grade serous carcinoma High-grade serous carcinoma | Polyclonal alteration of KRAS, BRAF Copy number alterations, BRAF, KRAS KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, and CDKN2A; gain of 1q or 18p; loss of 1p, 18q, and 22 TP53, PIK3CA, HLTF, POLQ, PIK3CB, MET, ARID1B, NF1, MRE11A, CCNE1, RB1, CDK12, PTEN, TP53BP1, BRCA1, BRCA2. Homologous recombination RNA repair defects, whole-genome duplication, MHC-II expression | WT1, estrogen receptor | [4,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30] |

| [31,32,33,34] | |||

| 1.2. Mucinous Mucinous cystadenoma and adenofibroma Mucinous borderline tumor Mucinous carcinoma 1.3. Endometrioid tumors Endometrioid cystadenoma and adenofibroma Endometrioid borderline tumor Endometrioid carcinoma 1.4. Clear cell tumors Clear cell cystadenoma and adenofibroma Clear cell borderline tumor Clear cell carcinoma 1.5. Seromucinous tumors Seromucinous cystadenoma and adenofibroma Seromucinous borderline tumor 1.6. Brenner tumors Brenner tumor Borderline Brenner tumor Malignant Brenner tumor 1.7. Other carcinomas Mesonephric-like adenocarcinoma Undifferentiated and dedifferentiated carcinoma Carcinosarcoma Mixed carcinoma | ARID1A TP53, RNF43, ELF3, GNAS, ERBB3, KLF5 | ||

ARID1A, CTNNB1, CTNNB1, PTEN, POLE, MSI, | AKT | [5,35,36,37,38,39,40] | |

| ARID1A ARID1A, PTEN, PIK3CA, TP53 | [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50] | ||

| ARID1A MDM2, PIK3CA NRAS, KRAS; gain of 1q or 18p; loss of 1p, 18q, and 22 | GATA3, TTF1, CD10 | [34] | |

| [10,32,33,51,52] | |||

| KIT, EGFR, HER2, TP53, PTEN, CHD4, BCOR, KRAS, PIK3CA, ARID1A, CTNNB1 | [17,26,36,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61] | ||

| 2. Mesenchymal 2.1. Endometrioid stromal sarcoma Low-grade endometrioid stromal sarcoma High-grade endometrioid stromal sarcoma 2.2. Smooth muscle tumors Leiomyoma Smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential Leiomyosarcoma 2.3. Ovarian myxoma | JAZF1::SUZ12 fusion | CD10 | [54,62,63] |

| YWHAE::FAM22 fusion | CD10 | ||

| CD10 | |||

| 3. Mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumors Adenosarcoma | CD10 | [54,62] | |

| 4. Sex cord–stromal tumors 4.1. Pure stromal tumors Fibroma Thecoma Sclerosing stromal tumor Microcystic stromal tumor Signet ring stromal tumor Leydig cell tumor Steroid cell tumor Fibrosarcoma 4.2. Pure sex cord tumors Adult granulosa cell tumor Juvenile granulosa cell tumor Sertoli cell tumor Sex cord tumor with annular tubules 4.3. Mixed sex cord–stromal tumors Sertoli–Leydig cell tumor Sex cord–stromal tumor, NOS Gynandroblastoma | FHL2::GLI2 fusion CTNNB1, APC — | [64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80] | |

| FOXL2 AKT1 | |||

| STK11 | |||

| DICER1, FOXL2 | |||

| DICER1 | |||

| 5. Germ cell tumors 5.1. Teratoma, benign 5.2. Immature teratoma, NOS 5.3. Dysgerminoma 5.4. Yolk sac tumor 5.5. Embryonal carcinoma | Isochromosome 12p Isochromosome 12p, KIT Isochromosome 12p Isochromosome 12p | AFP Sall4, OCT3/4, LDH Sall4, AFP Sall4, OCT3/4, SOX2, β-hCG, AFP β-hCG LDH, AFP, β-hCG | [12,13,69,72,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92] |

| 5.6. Choriocarcinoma, NOS 5.7. Mixed germ cell tumor 5.8. Monodermal teratomas and somatic type tumors arising from a dermoid cyst Struma ovarii, NOS Struma ovarii, malignant Strumal carcinoid Teratoma with malignant transformation Cystic teratoma, NOS 5.9. Germ cell sex cord–stromal tumors Gonadoblastoma, Mixed germ cell—sex cord–stromal tumor, unclassified | BRAF | PLAP, OCT4 | |

| OCT3/4 12p amplification | |||

| 6. Miscellaneous tumors Rete cystadenoma, adenoma and adenocarcinoma Wolffian tumor Solid pseudopapillary tumor Small-cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type (SCCOHT) Wilms tumor | CTNNB1 SMARCA4 | [45,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103] | |

| 7. Tumor-like lesions Follicle cyst Corpus luteum cyst Large solitary luteinized follicle cyst Hyperreactio luteinalis | [64,104] |

2.2. OC-Genetic Alterations Associated with Subtypes

3. OC—Current Therapeutic Strategies

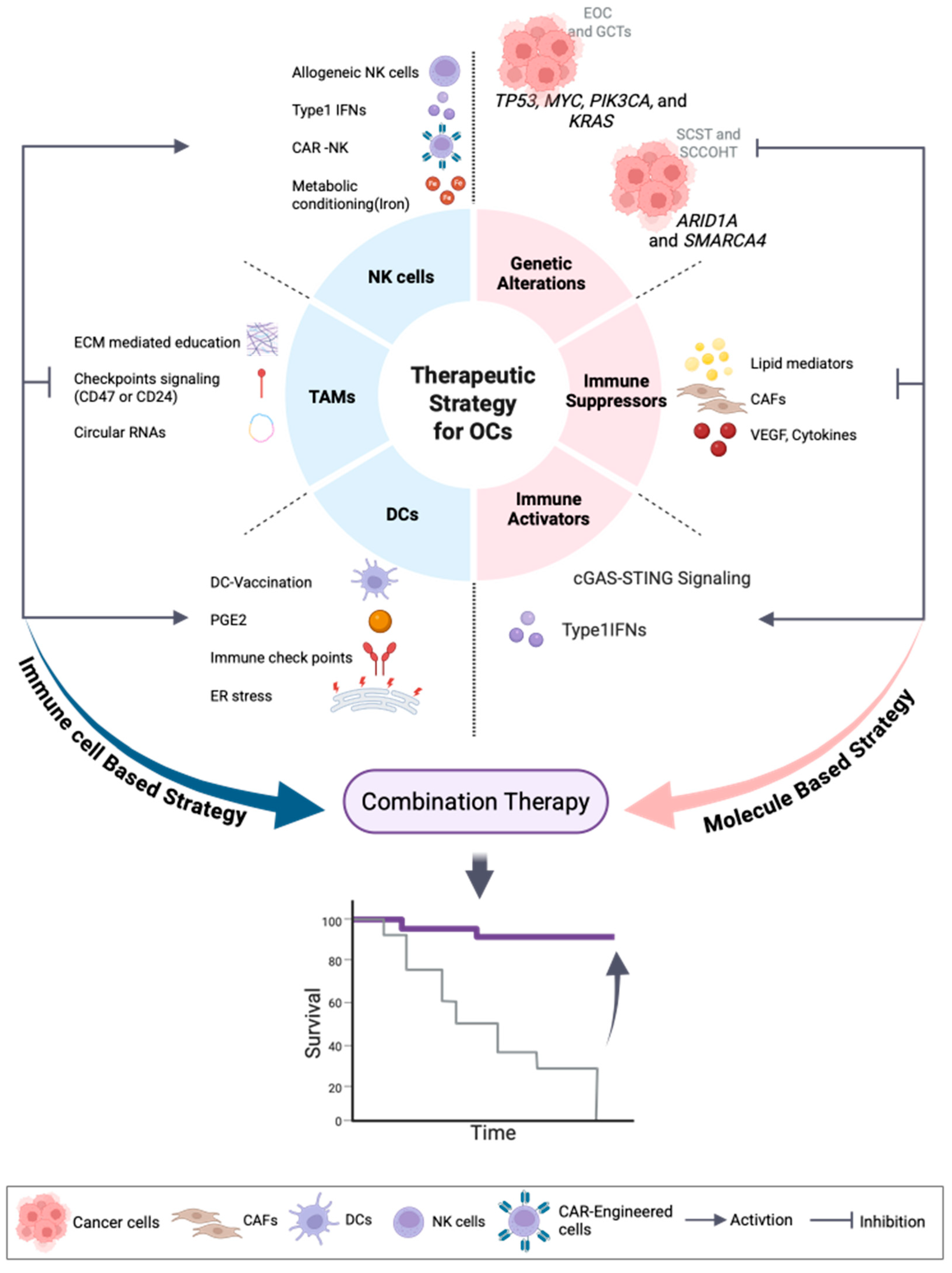

4. OC—Therapeutic Strategies Targeting TME

4.1. Lipid-Driven Immune Suppression in the Ovarian Cancer TME

4.1.1. Tumor-Intrinsic Lipid-Mediated Immunosuppression

4.1.2. Tumor-Extrinsic Lipid-Mediated Immunosuppression

4.2. Type I Interferon (IFN) and STING Activation Pathways in OC: Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Opportunities

4.3. DC-Based Immunotherapy and Reprogramming Strategies in OC

4.4. Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs) in OC: Reprogramming Immunosuppressive Niches Toward Antitumor Immunity

4.5. Natural Killer (NK) Cells in OC: Dysfunction, Engineering, and Combination Strategies

4.6. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) in Ovarian Cancer Targeting Fibroblast-Driven Oncogenic and Immunosuppressive Pathways

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sherman, R.L.; Firth, A.U.; Henley, S.J.; Siegel, R.L.; Negoita, S.; Sung, H.; Kohler, B.A.; Anderson, R.N.; Cucinelli, J.; Scott, S.; et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, featuring state-level statistics after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Cancer 2025, 131, e35833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, E.H.; Jung, K.W.; Park, N.J.; Kang, M.J.; Yun, E.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.E.; Kong, H.J.; Choi, K.S.; Yang, H.K.; et al. Cancer Statistics in Korea: Incidence, Mortality, Survival, and Prevalence in 2022. Cancer Res. Treat. 2025, 57, 312–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, B.S.; Park, E.H.; Ha, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, T.S.; Lee, K.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Jung, K.W.; Roh, J.W. Incidence and survival of gynecologic cancer including cervical, uterine, ovarian, vaginal, vulvar cancer and gestational trophoblastic neoplasia in Korea, 1999-2019: Korea Central Cancer Registry. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2023, 66, 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobel, M.; Kang, E.Y. The Evolution of Ovarian Carcinoma Subclassification. Cancers 2022, 14, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, A.; Santini, D.; Ceccarelli, C.; Santandrea, G.; Palicelli, A.; Acquaviva, G.; Chiarucci, F.; Rosini, F.; Ravegnini, G.; Pession, A.; et al. What Is New on Ovarian Carcinoma: Integrated Morphologic and Molecular Analysis Following the New 2020 World Health Organization Classification of Female Genital Tumors. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. In Female Genital Tumours, 5th ed.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Bi, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zheng, Z.J. Global Incidence of Ovarian Cancer According to Histologic Subtype: A Population-Based Cancer Registry Study. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2024, 10, e2300393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.I.; Chang, H.K.; Park, S.J.; Lim, J.; Won, Y.J.; Lim, M.C. The incidence and survival of cervical, ovarian, and endometrial cancer in Korea, 1999-2017: Korea Central Cancer Registry. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2021, 64, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matz, M.; Coleman, M.P.; Carreira, H.; Salmeron, D.; Chirlaque, M.D.; Allemani, C.; Group, C.W. Worldwide comparison of ovarian cancer survival: Histological group and stage at diagnosis (CONCORD-2). Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 144, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, L.C.; Cushing-Haugen, K.L.; Kobel, M.; Harris, H.R.; Berchuck, A.; Rossing, M.A.; Schildkraut, J.M.; Doherty, J.A. Invasive Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Survival by Histotype and Disease Stage. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortner, R.T.; Trewin-Nybraten, C.B.; Paulsen, T.; Langseth, H. Characterization of ovarian cancer survival by histotype and stage: A nationwide study in Norway. Int. J. Cancer 2023, 153, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Maria, F.; Amant, F.; Chiappa, V.; Paolini, B.; Bergamini, A.; Fruscio, R.; Corso, G.; Raspagliesi, F.; Bogani, G. Malignant germ cells tumor of the ovary. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2025, 36, e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray-Coquard, I.; Morice, P.; Lorusso, D.; Prat, J.; Oaknin, A.; Pautier, P.; Colombo, N.; Committee, E.G. Non-epithelial ovarian cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, iv1–iv18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangili, G.; Sigismondi, C.; Gadducci, A.; Cormio, G.; Scollo, P.; Tateo, S.; Ferrandina, G.; Greggi, S.; Candiani, M.; Lorusso, D. Outcome and risk factors for recurrence in malignant ovarian germ cell tumors: A MITO-9 retrospective study. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2011, 21, 1414–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdett, N.L.; Willis, M.O.; Alsop, K.; Hunt, A.L.; Pandey, A.; Hamilton, P.T.; Abulez, T.; Liu, X.; Hoang, T.; Craig, S.; et al. Multiomic analysis of homologous recombination-deficient end-stage high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat. Genet. 2023, 55, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdett, N.L.; Willis, M.O.; Pandey, A.; Twomey, L.; Alaei, S.; Australian Ovarian Cancer Study, G.; Bowtell, D.D.L.; Christie, E.L. Timing of whole genome duplication is associated with tumor-specific MHC-II depletion in serous ovarian cancer. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapel, D.B.; Joseph, N.M.; Krausz, T.; Lastra, R.R. An Ovarian Adenocarcinoma With Combined Low-grade Serous and Mesonephric Morphologies Suggests a Mullerian Origin for Some Mesonephric Carcinomas. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2018, 37, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, E.J.; Kurman, R.J.; Wang, M.; Oldt, R.; Wang, B.G.; Berman, D.M.; Shih Ie, M. Molecular genetic analysis of ovarian serous cystadenomas. Lab. Investig. 2004, 84, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisham, R.N.; Iyer, G.; Garg, K.; Delair, D.; Hyman, D.M.; Zhou, Q.; Iasonos, A.; Berger, M.F.; Dao, F.; Spriggs, D.R.; et al. BRAF mutation is associated with early stage disease and improved outcome in patients with low-grade serous ovarian cancer. Cancer 2013, 119, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Keathley, R.; Kim, U.; Cardenas, H.; Xie, P.; Wei, J.; Lengyel, E.; Nephew, K.P.; Zhao, G.; Fu, Z.; et al. Comparative transcriptomic, epigenomic and immunological analyses identify drivers of disparity in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. NPJ Genom. Med. 2024, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.M.; Anglesio, M.S.; Sharma, R.; Gilks, C.B.; Melnyk, N.; Chiew, Y.E.; deFazio, A.; Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group; Longacre, T.A.; Huntsman, D.G.; et al. Copy number aberrations in benign serous ovarian tumors: A case for reclassification? Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 7273–7282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, Y.R.; Ducie, J.A.; Arnold, A.G.; Kauff, N.D.; Vargas-Alvarez, H.A.; Sala, E.; Levine, D.A.; Soslow, R.A. Invasion Patterns of Metastatic Extrauterine High-grade Serous Carcinoma With BRCA Germline Mutation and Correlation With Clinical Outcomes. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2016, 40, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Wang, T.L.; Kurman, R.J.; Nakayama, K.; Velculescu, V.E.; Vogelstein, B.; Kinzler, K.W.; Papadopoulos, N.; Shih Ie, M. Low-grade serous carcinomas of the ovary contain very few point mutations. J. Pathol. 2012, 226, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelliher, L.; Yoeli-Bik, R.; Schweizer, L.; Lengyel, E. Molecular changes driving low-grade serous ovarian cancer and implications for treatment. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2024, 34, 1630–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malpica, A.; Wong, K.K. The molecular pathology of ovarian serous borderline tumors. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, i16–i19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluggage, W.G.; Vosmikova, H.; Laco, J. Ovarian Combined Low-grade Serous and Mesonephric-like Adenocarcinoma: Further Evidence for A Mullerian Origin of Mesonephric-like Adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2020, 39, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, R.; Selenica, P.; Brown, D.N.; Cheetham, R.K.; Chandramohan, R.; Claros, N.L.; Bouvier, N.; Cheng, D.T.; Soslow, R.A.; Weigelt, B.; et al. Somatic genetic alterations in synchronous and metachronous low-grade serous tumours and high-grade carcinomas of the adnexa. Histopathology 2019, 74, 638–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, K.K.; Tsang, Y.T.; Deavers, M.T.; Mok, S.C.; Zu, Z.; Sun, C.; Malpica, A.; Wolf, J.K.; Lu, K.H.; Gershenson, D.M. BRAF mutation is rare in advanced-stage low-grade ovarian serous carcinomas. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 177, 1611–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature 2011, 474, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneziani, A.C.; Gonzalez-Ochoa, E.; Alqaisi, H.; Madariaga, A.; Bhat, G.; Rouzbahman, M.; Sneha, S.; Oza, A.M. Heterogeneity and treatment landscape of ovarian carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 20, 820–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryland, G.L.; Hunter, S.M.; Doyle, M.A.; Caramia, F.; Li, J.; Rowley, S.M.; Christie, M.; Allan, P.E.; Stephens, A.N.; Bowtell, D.D.; et al. Mutational landscape of mucinous ovarian carcinoma and its neoplastic precursors. Genome. Med. 2015, 7, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidman, J.D.; Khedmati, F. Exploring the histogenesis of ovarian mucinous and transitional cell (Brenner) neoplasms and their relationship with Walthard cell nests: A study of 120 tumors. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2008, 132, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, M.; Simmer, F.; Bulten, J.; Ligtenberg, M.J.; Hollema, H.; van Vliet, S.; de Voer, R.M.; Kamping, E.J.; van Essen, D.F.; Ylstra, B.; et al. Two types of primary mucinous ovarian tumors can be distinguished based on their origin. Mod. Pathol. 2020, 33, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.H.; Mao, T.L.; Vang, R.; Ayhan, A.; Wang, T.L.; Kurman, R.J.; Shih Ie, M. Endocervical-type mucinous borderline tumors are related to endometrioid tumors based on mutation and loss of expression of ARID1A. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2012, 31, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConechy, M.K.; Ding, J.; Senz, J.; Yang, W.; Melnyk, N.; Tone, A.A.; Prentice, L.M.; Wiegand, K.C.; McAlpine, J.N.; Shah, S.P.; et al. Ovarian and endometrial endometrioid carcinomas have distinct CTNNB1 and PTEN mutation profiles. Mod. Pathol. 2014, 27, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euscher, E.D.; Bassett, R.; Duose, D.Y.; Lan, C.; Wistuba, I.; Ramondetta, L.; Ramalingam, P.; Malpica, A. Mesonephric-like Carcinoma of the Endometrium: A Subset of Endometrial Carcinoma With an Aggressive Behavior. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2020, 44, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamani, M.; Stuart, C.A.; Doherty, M.G. Increased steroid production by the ovarian stromal tissue of postmenopausal women with endometrial cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1992, 74, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noe, M.; Ayhan, A.; Wang, T.L.; Shih, I.M. Independent development of endometrial epithelium and stroma within the same endometriosis. J. Pathol. 2018, 245, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra-Herran, C.; Lerner-Ellis, J.; Xu, B.; Khalouei, S.; Bassiouny, D.; Cesari, M.; Ismiil, N.; Nofech-Mozes, S. Molecular-based classification algorithm for endometrial carcinoma categorizes ovarian endometrioid carcinoma into prognostically significant groups. Mod. Pathol. 2017, 30, 1748–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, N.; Tsunoda, H.; Nishida, M.; Morishita, Y.; Takimoto, Y.; Kubo, T.; Noguchi, M. Loss of heterozygosity on 10q23.3 and mutation of the tumor suppressor gene PTEN in benign endometrial cyst of the ovary: Possible sequence progression from benign endometrial cyst to endometrioid carcinoma and clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 7052–7056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bennett, J.A.; Morales-Oyarvide, V.; Campbell, S.; Longacre, T.A.; Oliva, E. Mismatch Repair Protein Expression in Clear Cell Carcinoma of the Ovary: Incidence and Morphologic Associations in 109 Cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2016, 40, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, I.G.; Russell, S.E.; Choong, D.Y.; Montgomery, K.G.; Ciavarella, M.L.; Hooi, C.S.; Cristiano, B.E.; Pearson, R.B.; Phillips, W.A. Mutation of the PIK3CA gene in ovarian and breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 7678–7681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlander, M.L.; Russell, K.; Millis, S.; Gatalica, Z.; Bender, R.; Voss, A. Molecular Profiling of Clear Cell Ovarian Cancers: Identifying Potential Treatment Targets for Clinical Trials. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2016, 26, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Wang, T.L.; Shih Ie, M.; Mao, T.L.; Nakayama, K.; Roden, R.; Glas, R.; Slamon, D.; Diaz, L.A., Jr.; Vogelstein, B.; et al. Frequent mutations of chromatin remodeling gene ARID1A in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Science 2010, 330, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnezis, A.N.; Wang, Y.; Ramos, P.; Hendricks, W.P.; Oliva, E.; D’Angelo, E.; Prat, J.; Nucci, M.R.; Nielsen, T.O.; Chow, C.; et al. Dual loss of the SWI/SNF complex ATPases SMARCA4/BRG1 and SMARCA2/BRM is highly sensitive and specific for small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcaemic type. J. Pathol. 2016, 238, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, K.T.; Mao, T.L.; Jones, S.; Veras, E.; Ayhan, A.; Wang, T.L.; Glas, R.; Slamon, D.; Velculescu, V.E.; Kuman, R.J.; et al. Frequent activating mutations of PIK3CA in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 174, 1597–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, F.I.; Gilks, C.B.; Mulligan, A.M.; Ryan, P.; Allo, G.; Sy, K.; Shaw, P.A.; Pollett, A.; Clarke, B.A. Prevalence of loss of expression of DNA mismatch repair proteins in primary epithelial ovarian tumors. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2012, 31, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra-Herran, C.; Bassiouny, D.; Lerner-Ellis, J.; Olkhov-Mitsel, E.; Ismiil, N.; Hogen, L.; Vicus, D.; Nofech-Mozes, S. p53, Mismatch Repair Protein, and POLE Abnormalities in Ovarian Clear Cell Carcinoma: An Outcome-based Clinicopathologic Analysis. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2019, 43, 1591–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, M.; Kobel, M.; Garsed, D.W.; Fereday, S.; Pandey, A.; Etemadmoghadam, D.; Hendley, J.; Kawabata, A.; Noguchi, D.; Yanaihara, N.; et al. Survival Following Chemotherapy in Ovarian Clear Cell Carcinoma Is Not Associated with Pathological Misclassification of Tumor Histotype. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 3962–3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.K.; Bashashati, A.; Anglesio, M.S.; Cochrane, D.R.; Grewal, D.S.; Ha, G.; McPherson, A.; Horlings, H.M.; Senz, J.; Prentice, L.M.; et al. Genomic consequences of aberrant DNA repair mechanisms stratify ovarian cancer histotypes. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 856–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurman, R.J.; Shih Ie, M. The origin and pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer: A proposed unifying theory. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2010, 34, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Huang, W.; Finkelman, B.S.; Zhang, H. Malignant Brenner tumor of the ovary: Pathologic evaluation, molecular insights and clinical management. Hum. Pathol. Rep. 2024, 36, 300739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramphal, K.; Hadfield, M.J.; Bandera, C.M.; Hart, J.; Dizon, D.S. Genomic and Molecular Characteristics of Ovarian Carcinosarcoma. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 46, 572–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbatani, N.; Olawaiye, A.B.; Prat, J. Uterine sarcomas. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2018, 143, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, E.M.; Fix, D.J.; Sebastiao, A.P.M.; Selenica, P.; Ferrando, L.; Kim, S.H.; Stylianou, A.; Da Cruz Paula, A.; Pareja, F.; Smith, E.S.; et al. Mesonephric and mesonephric-like carcinomas of the female genital tract: Molecular characterization including cases with mixed histology and matched metastases. Mod. Pathol. 2021, 34, 1570–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyoshi, K.; Kawauchi, S.; Kaku, T.; Nakano, H.; Tsuneyoshi, M. Prognostic factors in ovarian carcinosarcoma: A clinicopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of 23 cases. Histopathology 2000, 37, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Bose, D.; Bhattacharyya, N.K.; Biswas, P.K. Carcinosarcoma of ovary with its various immunohistochemical expression: Report of a rare case. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2015, 11, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Stransky, N.; McCord, C.L.; Cerami, E.; Lagowski, J.; Kelly, D.; Angiuoli, S.V.; Sausen, M.; Kann, L.; Shukla, M.; et al. Genomic analyses of gynaecologic carcinosarcomas reveal frequent mutations in chromatin remodelling genes. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, M.; Tsuda, H.; Kimura, M.; Okamoto, S.; Kita, T.; Kasamatsu, T.; Yamada, T.; Kikuchi, Y.; Honjo, H.; Matsubara, O. Different expression patterns of KIT, EGFR, and HER-2 (c-erbB-2) oncoproteins between epithelial and mesenchymal components in uterine carcinosarcoma. Cancer Sci. 2003, 94, 986–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Bellone, S.; Lopez, S.; Thakral, D.; Schwab, C.; English, D.P.; Black, J.; Cocco, E.; Choi, J.; Zammataro, L.; et al. Mutational landscape of uterine and ovarian carcinosarcomas implicates histone genes in epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 12238–12243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Tang, C.; Liu, P.; Hao, H. Carcinosarcoma of the ovary: A case report and literature review. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1278300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, P.B.; Scully, R.E. Uterine tumors with mixed epithelial and mesenchymal elements. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 1988, 5, 199–222. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.S.; Kohler, M.F.; Marks, J.R.; Bast, R.C., Jr.; Boyd, J.; Berchuck, A. Mutation and overexpression of the p53 tumor suppressor gene frequently occurs in uterine and ovarian sarcomas. Obstet. Gynecol. 1994, 83, 118–124. [Google Scholar]

- McCluggage, W.G.; Singh, N.; Gilks, C.B. Key changes to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of female genital tumours introduced in the 5th edition (2020). Histopathology 2022, 80, 762–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Agha, O.M.; Huwait, H.F.; Chow, C.; Yang, W.; Senz, J.; Kalloger, S.E.; Huntsman, D.G.; Young, R.H.; Gilks, C.B. FOXL2 is a sensitive and specific marker for sex cord-stromal tumors of the ovary. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2011, 35, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buza, N.; Wong, S.; Hui, P. FOXL2 Mutation Analysis of Ovarian Sex Cord-Stromal Tumors: Genotype-Phenotype Correlation With Diagnostic Considerations. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2018, 37, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conlon, N.; Schultheis, A.M.; Piscuoglio, S.; Silva, A.; Guerra, E.; Tornos, C.; Reuter, V.E.; Soslow, R.A.; Young, R.H.; Oliva, E.; et al. A survey of DICER1 hotspot mutations in ovarian and testicular sex cord-stromal tumors. Mod. Pathol. 2015, 28, 1603–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goulvent, T.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Borel, S.; Haddad, V.; Devouassoux-Shisheboran, M.; Vacher-Lavenu, M.C.; Pujade-Laurraine, E.; Savina, A.; Maillet, D.; Gillet, G.; et al. DICER1 and FOXL2 mutations in ovarian sex cord-stromal tumours: A GINECO Group study. Histopathology 2016, 68, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michal, M.; Vanecek, T.; Sima, R.; Mukensnabl, P.; Hes, O.; Kazakov, D.V.; Matoska, J.; Zuntova, A.; Dvorak, V.; Talerman, A. Mixed germ cell sex cord-stromal tumors of the testis and ovary. Morphological, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of seven cases. Virchows Arch. 2006, 448, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Kock, L.; Terzic, T.; McCluggage, W.G.; Stewart, C.J.R.; Shaw, P.; Foulkes, W.D.; Clarke, B.A. DICER1 Mutations Are Consistently Present in Moderately and Poorly Differentiated Sertoli-Leydig Cell Tumors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2017, 41, 1178–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devouassoux-Shisheboran, M.; Silver, S.A.; Tavassoli, F.A. Wolffian adnexal tumor, so-called female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin (FATWO): Immunohistochemical evidence in support of a Wolffian origin. Hum. Pathol. 1999, 30, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, D.; Jayraj, A.; Olearo, E.; Capasso, I.; Hsu, H.C.; Tzur, Y.; Piedimonte, S.; Jugeli, B.; Santana, B.N.; De Vitis, L.A.; et al. Primary versus interval cytoreductive surgery in patients with rare epithelial or non-epithelial ovarian cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2025, 35, 101664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heravi-Moussavi, A.; Anglesio, M.S.; Cheng, S.W.; Senz, J.; Yang, W.; Prentice, L.; Fejes, A.P.; Chow, C.; Tone, A.; Kalloger, S.E.; et al. Recurrent somatic DICER1 mutations in nonepithelial ovarian cancers. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnezis, A.N.; Wang, Y.; Keul, J.; Tessier-Cloutier, B.; Magrill, J.; Kommoss, S.; Senz, J.; Yang, W.; Proctor, L.; Schmidt, D.; et al. DICER1 and FOXL2 Mutation Status Correlates With Clinicopathologic Features in Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig Cell Tumors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2019, 43, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Da Cruz Paula, A.; Basili, T.; Dopeso, H.; Bi, R.; Pareja, F.; da Silva, E.M.; Gularte-Merida, R.; Sun, Z.; Fujisawa, S.; et al. Identification of recurrent FHL2-GLI2 oncogenic fusion in sclerosing stromal tumors of the ovary. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meurgey, A.; Descotes, F.; Mery-Lamarche, E.; Devouassoux-Shisheboran, M. Lack of mutation of DICER1 and FOXL2 genes in microcystic stromal tumor of the ovary. Virchows Arch. 2017, 470, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, K.A.P.; Harris, A.K.; Finch, M.; Dehner, L.P.; Brown, J.B.; Gershenson, D.M.; Young, R.H.; Field, A.; Yu, W.; Turner, J.; et al. DICER1-related Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor and gynandroblastoma: Clinical and genetic findings from the International Ovarian and Testicular Stromal Tumor Registry. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 147, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchrakian, N.; Oliva, E.; Chong, A.S.; Rivera-Polo, B.; Bennett, J.A.; Nucci, M.R.; Sah, S.; Schoolmeester, J.K.; van der Griend, R.A.; Foulkes, W.D.; et al. Ovarian Signet-ring Stromal Tumor: A Morphologic, Immunohistochemical, and Molecular Study of 7 Cases With Discussion of the Differential Diagnosis. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2022, 46, 1599–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tao, L.; Yin, C.; Wang, W.; Zou, H.; Ren, Y.; Liang, W.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, W.; Jia, W.; et al. Ovarian microcystic stromal tumor with undetermined potential: Case study with molecular analysis and literature review. Hum. Pathol. 2018, 78, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabban, J.T.; Karnezis, A.N.; Devine, W.P. Practical roles for molecular diagnostic testing in ovarian adult granulosa cell tumour, Sertoli-Leydig cell tumour, microcystic stromal tumour and their mimics. Histopathology 2020, 76, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.; Derr, V.; Heinrich, M.C.; Crum, C.P.; Fletcher, J.A.; Corless, C.L.; Nose, V. BRAF in papillary thyroid carcinoma of ovary (struma ovarii). Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2007, 31, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cools, M.; Looijenga, L.H.; Wolffenbuttel, K.P.; Drop, S.L. Disorders of sex development: Update on the genetic background, terminology and risk for the development of germ cell tumors. World J. Pediatr. 2009, 5, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riopel, M.A.; Spellerberg, A.; Griffin, C.A.; Perlman, E.J. Genetic analysis of ovarian germ cell tumors by comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 3105–3110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stoop, H.; Honecker, F.; van de Geijn, G.J.; Gillis, A.J.; Cools, M.C.; de Boer, M.; Bokemeyer, C.; Wolffenbuttel, K.P.; Drop, S.L.; de Krijger, R.R.; et al. Stem cell factor as a novel diagnostic marker for early malignant germ cells. J. Pathol. 2008, 216, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Roth, L.M.; Zhang, S.; Wang, M.; Morton, M.J.; Zheng, W.; Abdul Karim, F.W.; Montironi, R.; Lopez-Beltran, A. KIT gene mutation and amplification in dysgerminoma of the ovary. Cancer 2011, 117, 2096–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Zhang, S.; Talerman, A.; Roth, L.M. Morphologic, immunohistochemical, and fluorescence in situ hybridization study of ovarian embryonal carcinoma with comparison to solid variant of yolk sac tumor and immature teratoma. Hum. Pathol. 2010, 41, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cossu-Rocca, P.; Zhang, S.; Roth, L.M.; Eble, J.N.; Zheng, W.; Karim, F.W.; Michael, H.; Emerson, R.E.; Jones, T.D.; Hattab, E.M.; et al. Chromosome 12p abnormalities in dysgerminoma of the ovary: A FISH analysis. Mod. Pathol. 2006, 19, 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersmus, R.; Kalfa, N.; de Leeuw, B.; Stoop, H.; Oosterhuis, J.W.; de Krijger, R.; Wolffenbuttel, K.P.; Drop, S.L.; Veitia, R.A.; Fellous, M.; et al. FOXL2 and SOX9 as parameters of female and male gonadal differentiation in patients with various forms of disorders of sex development (DSD). J. Pathol. 2008, 215, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Malpica, A.; Ramalingam, P.; Euscher, E.D.; Fuller, G.N.; Liu, J. Gliomatosis peritonei: A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 21 cases. Mod. Pathol. 2015, 28, 1613–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulos, C.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, S.; Gersell, D.J.; Ulbright, T.M. Analysis of ovarian teratomas for isochromosome 12p: Evidence supporting a dual histogenetic pathway for teratomatous elements. Mod. Pathol. 2006, 19, 766–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snir, O.L.; DeJoseph, M.; Wong, S.; Buza, N.; Hui, P. Frequent homozygosity in both mature and immature ovarian teratomas: A shared genetic basis of tumorigenesis. Mod. Pathol. 2017, 30, 1467–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowski, L.; Mattina, J.; Schonberger, S.; Murray, M.J.; Choong, C.S.; Huntsman, D.G.; Reis-Filho, J.S.; McCluggage, W.G.; Nicholson, J.C.; Coleman, N.; et al. DICER1 hotspot mutations in non-epithelial gonadal tumours. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 2744–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupryjanczyk, J.; Dansonka-Mieszkowska, A.; Moes-Sosnowska, J.; Plisiecka-Halasa, J.; Szafron, L.; Podgorska, A.; Rzepecka, I.K.; Konopka, B.; Budzilowska, A.; Rembiszewska, A.; et al. Ovarian small cell carcinoma of hypercalcemic type—Evidence of germline origin and SMARCA4 gene inactivation. a pilot study. Pol. J. Pathol. 2013, 64, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandra, C.A.; Attili, V.S.S.; Dadhich, H.P.; Kumari, A.; Appaji, L.; Giri, G.V.; Mukharjee, G. Extrarenal Wilms’ tumor: A report of two cases and review of literature. J. Indian Assoc. Pediatr. Surg. 2007, 12, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kominami, A.; Fujino, M.; Murakami, H.; Ito, M. beta-catenin mutation in ovarian solid pseudopapillary neoplasm. Pathol. Int. 2014, 64, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Patel, N.; Patil, P.; Paquette, C.; Mathews, C.A.; Lawrence, W.D. Primary Ovarian Solid Pseudopapillary Neoplasm With CTNNB1 c.98C>G (p.S33C) Point Mutation. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2018, 37, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelinic, P.; Mueller, J.J.; Olvera, N.; Dao, F.; Scott, S.N.; Shah, R.; Gao, J.; Schultz, N.; Gonen, M.; Soslow, R.A.; et al. Recurrent SMARCA4 mutations in small cell carcinoma of the ovary. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 424–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, P.; Karnezis, A.N.; Craig, D.W.; Sekulic, A.; Russell, M.L.; Hendricks, W.P.; Corneveaux, J.J.; Barrett, M.T.; Shumansky, K.; Yang, Y.; et al. Small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type, displays frequent inactivating germline and somatic mutations in SMARCA4. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 427–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witkowski, L.; Carrot-Zhang, J.; Albrecht, S.; Fahiminiya, S.; Hamel, N.; Tomiak, E.; Grynspan, D.; Saloustros, E.; Nadaf, J.; Rivera, B.; et al. Germline and somatic SMARCA4 mutations characterize small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahiminiya, S.; Witkowski, L.; Nadaf, J.; Carrot-Zhang, J.; Goudie, C.; Hasselblatt, M.; Johann, P.; Kool, M.; Lee, R.S.; Gayden, T.; et al. Molecular analyses reveal close similarities between small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type and atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 1732–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witkowski, L.; Goudie, C.; Ramos, P.; Boshari, T.; Brunet, J.S.; Karnezis, A.N.; Longy, M.; Knost, J.A.; Saloustros, E.; McCluggage, W.G.; et al. The influence of clinical and genetic factors on patient outcome in small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 141, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdhof, D.; Johann, P.D.; Spohn, M.; Bockmayr, M.; Safaei, S.; Joshi, P.; Masliah-Planchon, J.; Ho, B.; Andrianteranagna, M.; Bourdeaut, F.; et al. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors (ATRTs) with SMARCA4 mutation are molecularly distinct from SMARCB1-deficient cases. Acta Neuropathol. 2021, 141, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommoss, F.K.; Tessier-Cloutier, B.; Witkowski, L.; Forgo, E.; Koelsche, C.; Kobel, M.; Foulkes, W.D.; Lee, C.H.; Kolin, D.L.; von Deimling, A.; et al. Cellular context determines DNA methylation profiles in SWI/SNF-deficient cancers of the gynecologic tract. J. Pathol. 2022, 257, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Rafael, Z.; Bider, D.; Menashe, Y.; Maymon, R.; Zolti, M.; Mashiach, S. Follicular and luteal cysts after treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog for in vitro fertilization. Fertil. Steril. 1990, 53, 1091–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, M.H.; Tokheim, C.; Porta-Pardo, E.; Sengupta, S.; Bertrand, D.; Weerasinghe, A.; Colaprico, A.; Wendl, M.C.; Kim, J.; Reardon, B.; et al. Comprehensive Characterization of Cancer Driver Genes and Mutations. Cell 2018, 173, 371–385.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehir, A.; Benayed, R.; Shah, R.H.; Syed, A.; Middha, S.; Kim, H.R.; Srinivasan, P.; Gao, J.; Chakravarty, D.; Devlin, S.M.; et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning-Geist, B.; Gordhandas, S.; Liu, Y.L.; Zhou, Q.; Iasonos, A.; Da Cruz Paula, A.; Mandelker, D.; Long Roche, K.; Zivanovic, O.; Maio, A.; et al. MAPK Pathway Genetic Alterations Are Associated with Prolonged Overall Survival in Low-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 4456–4465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkin, R.; Oh, J.H.; Liu, Y.L.; Selenica, P.; Weigelt, B.; Reis-Filho, J.S.; Zamarin, D.; Deasy, J.O.; Norton, L.; Levine, A.J.; et al. Geometric network analysis provides prognostic information in patients with high grade serous carcinoma of the ovary treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. NPJ Genom. Med. 2021, 6, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matuszczak, M.; Kiljanczyk, A.; Marciniak, W.; Derkacz, R.; Stempa, K.; Baszuk, P.; Bryskiewicz, M.; Cybulski, C.; Debniak, T.; Jacek, G.; et al. Blood molybdenum level as a marker of cancer risk on BRCA1 carriers. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 2024, 22, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.A.; Soukar, J.; Zulkifli, M.; Kersey, A.; Lokhande, G.; Ghosh, S.; Murali, A.; Garza, N.M.; Kaur, H.; Keeney, J.N.; et al. Atomic vacancies of molybdenum disulfide nanoparticles stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giornelli, G.H. Management of relapsed ovarian cancer: A review. Springerplus 2016, 5, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016, 66, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray-Coquard, I.; Leary, A.; Pignata, S.; Cropet, C.; Gonzalez-Martin, A.; Marth, C.; Nagao, S.; Vergote, I.; Colombo, N.; Maenpaa, J.; et al. Olaparib plus bevacizumab first-line maintenance in ovarian cancer: Final overall survival results from the PAOLA-1/ENGOT-ov25 trial. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiSilvestro, P.; Banerjee, S.; Colombo, N.; Scambia, G.; Kim, B.G.; Oaknin, A.; Friedlander, M.; Lisyanskaya, A.; Floquet, A.; Leary, A.; et al. Overall Survival With Maintenance Olaparib at a 7-Year Follow-Up in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer and a BRCA Mutation: The SOLO1/GOG 3004 Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca-Escalona, J.; Bodder, J.; Subtil, B.; Sanchez-Sanchez, M.; Vidal-Manrique, M.; Sweep, M.W.D.; Fauerbach, J.A.; Cambi, A.; Florez-Grau, G.; de Vries, J.M. EP2/EP4 targeting prevents tumor-derived PGE2-mediated immunosuppression in cDC2s. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2024, 116, 1554–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, S.; Thomas, S.N.; Simmons, G.E., Jr. Targeting lipid metabolism in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Oncotarget 2022, 13, 768–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surendran, A.; Jamalkhah, M.; Poutou, J.; Birtch, R.; Lawson, C.; Dave, J.; Crupi, M.J.F.; Mayer, J.; Taylor, V.; Petryk, J.; et al. Fatty acid transport protein inhibition sensitizes breast and ovarian cancers to oncolytic virus therapy via lipid modulation of the tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1099459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.R.; Yung, M.M.H.; Xuan, Y.; Zhan, S.; Leung, L.L.; Liang, R.R.; Leung, T.H.Y.; Yang, H.; Xu, D.; Sharma, R.; et al. Author Correction: Targeting of lipid metabolism with a metabolic inhibitor cocktail eradicates peritoneal metastases in ovarian cancer cells. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.Y.; Deng, F.; Wei, X.W.; Ma, C.C.; Luo, M.; Zhang, P.; Sang, Y.X.; Liang, X.; Liu, L.; Qin, H.X.; et al. Ovarian cancer treatment with a tumor-targeting and gene expression-controllable lipoplex. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, B. cGAS/STING signaling pathway in gynecological malignancies: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic values. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1525736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Kim, H.J.; Wang, Q.; Kearns, M.; Jiang, T.; Ohlson, C.E.; Li, B.B.; Xie, S.; Liu, J.F.; Stover, E.H.; et al. PARP Inhibition Elicits STING-Dependent Antitumor Immunity in Brca1-Deficient Ovarian Cancer. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 2972–2980.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, J.; Peng, J.; Feng, J.; Maurer, J.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Yao, S.; Chu, R.; Pan, X.; Li, J.; et al. Niraparib exhibits a synergistic anti-tumor effect with PD-L1 blockade by inducing an immune response in ovarian cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelison, R.; Biswas, K.; Llaneza, D.C.; Harris, A.R.; Sosale, N.G.; Lazzara, M.J.; Landen, C.N. CX-5461 Treatment Leads to Cytosolic DNA-Mediated STING Activation in Ovarian Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, L.; Weng, L.; Tian, H.; Wu, Z.; Tan, X.; Ge, X.; et al. Deubiquitinase USP35 restrains STING-mediated interferon signaling in ovarian cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Zhang, L.; Shen, J.; Lai, F.; Han, W.; Liu, X. Knockdown of CENPM activates cGAS-STING pathway to inhibit ovarian cancer by promoting pyroptosis. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, X.; Nie, X.C.; Liu, Y.S.; Zhou, Y.; Niu, J.M. Manganese and IL-12 treatment alters the ovarian tumor microenvironment. Aging 2024, 16, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Xu, F.; Liu, T.; Ye, Y.; Xu, S. NAD(+) Metabolism-Mediated SURF4-STING Axis Enhances T-Cell Anti-Tumor Effects in the Ovarian Cancer Microenvironment. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, L.; Shen, M.; Tong, X.; Zhao, D.; Xiao, H.; Li, B. Polymer-PARPi Conjugates Delivering USP1i for Maximizing Synthetic Lethality to Stimulate STING Pathway in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Adv. Mater. 2025, e12962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, C.S.; Teran-Cabanillas, E.; Cubillos-Ruiz, J.R. Dendritic cell rehab: New strategies to unleash therapeutic immunity in ovarian cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2017, 66, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galpin, K.J.C.; Rodriguez, G.M.; Maranda, V.; Cook, D.P.; Macdonald, E.; Murshed, H.; Zhao, S.; McCloskey, C.W.; Chruscinski, A.; Levy, G.A.; et al. FGL2 promotes tumour growth and attenuates infiltration of activated immune cells in melanoma and ovarian cancer models. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; He, T.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, H.; Wu, Y.; Guo, H. Dendritic Cell Vaccines in Ovarian Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 613773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, A.A.; Deschoemaeker, S.; Allonsius, L.; Coosemans, A.; Laoui, D. Dendritic Cell Vaccines: A Promising Approach in the Fight against Ovarian Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, W.; Huang, J.; Li, F.; Sheng, J.; Song, H.; Chen, Y. Development of a Dendritic Cell/Tumor Cell Fusion Cell Membrane Nano-Vaccine for the Treatment of Ovarian Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 828263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tang, D.; Xiao, H.; Li, B.; Shang, K.; Zhao, D. Activating the cGAS-STING Pathway by Manganese-Based Nanoparticles Combined with Platinum-Based Nanoparticles for Enhanced Ovarian Cancer Immunotherapy. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 4346–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puttock, E.H.; Tyler, E.J.; Manni, M.; Maniati, E.; Butterworth, C.; Burger Ramos, M.; Peerani, E.; Hirani, P.; Gauthier, V.; Liu, Y.; et al. Extracellular matrix educates an immunoregulatory tumor macrophage phenotype found in ovarian cancer metastasis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, Y. KLHDC8A knockdown in normal ovarian epithelial cells promoted the polarization of pro-tumoral macrophages via the C5a/C5aR/p65 NFκB signaling pathway. Cell Immunol. 2025, 409–410, 104913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, X.; Lei, T.; Fang, J.; Liu, X.; Fu, H.; Li, Y.; Chu, W.; Jiang, P.; Tong, C.; Qi, H.; et al. Blockade of C5a receptor unleashes tumor-associated macrophage antitumor response and enhances CXCL9-dependent CD8(+) T cell activity. Mol. Ther. 2024, 32, 469–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wei, H.; Gao, P.; Yu, H.; Wang, K.; Fu, Z.; Ju, B.; Zhao, M.; Dong, S.; Li, Z.; et al. CD47 promotes ovarian cancer progression by inhibiting macrophage phagocytosis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 39021–39032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, H.; Yang, Y.; Kang, Y.; He, R.; Zhou, B.; Guo, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Ge, C.; et al. Dual blockade of CD47 and CD24 signaling using a novel bispecific antibody fusion protein enhances macrophage immunotherapy. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2023, 31, 100747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhani, N.J.; Stewart, D.; Richardson, D.L.; Dockery, L.E.; Van Le, L.; Call, J.; Rangwala, F.; Wang, G.; Ma, B.; Metenou, S.; et al. First-in-human phase I trial of the bispecific CD47 inhibitor and CD40 agonist Fc-fusion protein, SL-172154 in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e010565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Luo, F.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, W.; Xiang, T.; Pan, Q.; Cai, L.; Zhao, J.; Weng, D.; Li, Y.; et al. CircITGB6 promotes ovarian cancer cisplatin resistance by resetting tumor-associated macrophage polarization toward the M2 phenotype. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e004029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vledder, A.; Zeeburg, H.v.; Brummel, K.; Eerkens, A.L.; Rooij, N.v.; Plat, A.; Rovers, J.; Bruyn, M.d.; Nijman, H. Successful induction of tumor-directed immune responses in high grade serious ovarian carcinoma patients after primary treatment using a whole tumor cell vaccine. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 5566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeneman, B.; Schreibelt, G.; Duiveman-de Boer, T.; Bos, K.; van Oorschot, T.; Pots, J.; Scharenborg, N.; de Boer, A.; Hins-de Bree, S.; de Haas, N.; et al. NEOadjuvant Dendritic cell therapy added to first line standard of care in advanced epithelial Ovarian Cancer (NEODOC): Protocol of a first-in-human, exploratory, single-centre phase I/II trial in the Netherlands. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e102184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiss, K.A.; Angelos, M.G.; Dees, E.C.; Yuan, Y.; Ueno, N.T.; Pohlmann, P.R.; Johnson, M.L.; Chao, J.; Shestova, O.; Serody, J.S.; et al. CAR-macrophage therapy for HER2-overexpressing advanced solid tumors: A phase 1 trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1171–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Zuo, D.; Xu, J.; Feng, Y.; Xue, D.; Zhang, L.; Lin, L.; Zhang, J. A clinical study of autologous chimeric antigen receptor macrophage targeting mesothelin shows safety in ovarian cancer therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, H.; Lian, H.; Yang, S.; Liu, M.; He, J.; Cao, B.; Chen, D.; Hu, Y.; Zhi, C.; et al. NK-92MI Cells Engineered with Anti-claudin-6 Chimeric Antigen Receptors in Immunotherapy for Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 20, 1578–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knisely, A.; Rafei, H.; Basar, R.; Banerjee, P.P.; Metwalli, Z.; Lito, K.; Fellman, B.M.; Yuan, Y.; Wolff, R.A.; Morelli, M.P.; et al. Phase I/II study of TROP2 CAR engineered IL15-transduced cord blood-derived NK cells delivered intraperitoneally for the management of platinum resistant ovarian cancer, mesonephric-like adenocarcinoma, and pancreatic cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, TPS5626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VandenHeuvel, S.N.; Chau, E.; Mohapatra, A.; Dabbiru, S.; Roy, S.; O’Connell, C.; Kamat, A.; Godin, B.; Raghavan, S.A. Macrophage Checkpoint Nanoimmunotherapy Has the Potential to Reduce Malignant Progression in Bioengineered In Vitro Models of Ovarian Cancer. ACS Appl. Bio. Mater. 2024, 7, 7871–7882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Hilliard, T.S.; Wang, Z.; Johnson, J.; Wang, W.; Harper, E.I.; Ott, C.; O’Brien, C.; Campbell, L.; et al. Host obesity alters the ovarian tumor immune microenvironment and impacts response to standard of care chemotherapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 42, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, J.J.; Barlesi, F.; Chung, K.; Tolcher, A.W.; Kelly, K.; Hollebecque, A.; Le Tourneau, C.; Subbiah, V.; Tsai, F.; Kao, S.; et al. Phase I study of ABBV-428, a mesothelin-CD40 bispecific, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeku, O.O.; Barve, M.; Tan, W.W.; Wang, J.; Patnaik, A.; LoRusso, P.; Richardson, D.L.; Naqash, A.R.; Lynam, S.K.; Fu, S.; et al. Myeloid targeting antibodies PY159 and PY314 for platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e010959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, R.J.A.; Hoogstad-van Evert, J.S.; Hagemans, I.M.; Brummelman, J.; van Ens, D.; de Jonge, P.; Hooijmaijers, L.; Mahajan, S.; van der Waart, A.B.; Hermans, C.; et al. Increased peritoneal TGF-beta1 is associated with ascites-induced NK-cell dysfunction and reduced survival in high-grade epithelial ovarian cancer. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1448041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta, J.C.; Bahr, J.M.; Basu, S.; O’Donnell, J.T.; Barua, A. Expression of CISH, an Inhibitor of NK Cell Function, Increases in Association with Ovarian Cancer Development and Progression. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, T.A.; Salvagno, C.; Chae, C.S.; Awasthi, D.; Giovanelli, P.; Marin Falco, M.; Hwang, S.M.; Teran-Cabanillas, E.; Suominen, L.; Yamazaki, T.; et al. Iron Chelation Therapy Elicits Innate Immune Control of Metastatic Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 1901–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarannum, M.A.-O.; Dinh, K.A.-O.X.; Vergara, J.A.-O.; Birch, G.; Abdulhamid, Y.A.-O.; Kaplan, I.A.-O.; Ay, O.; Maia, A.A.-O.; Beaver, O.; Sheffer, M.A.-O.; et al. CAR memory-like NK cells targeting the membrane proximal domain of mesothelin demonstrate promising activity in ovarian cancer. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadn0881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Shen, X.; Xia, C.; Hu, F.; Huang, D.; Weng, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, L.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Mesothelin CAR-engineered NK cells derived from human embryonic stem cells suppress the progression of human ovarian cancer in animals. Cell Prolif. 2024, 57, e13727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, N.; Xia, Y.; Kelly, J.J.; Sanchez-Pupo, R.; Martinez, F.; Fox, M.S.; Thiessen, J.D.; Hicks, J.W.; Scholl, T.J.; Ronald, J.A. Imaging CAR-NK cells targeted to HER2 ovarian cancer with human sodium-iodide symporter-based positron emission tomography. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2024, 51, 3176–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quixabeira, D.C.A.; Pakola, S.; Jirovec, E.; Havunen, R.; Basnet, S.; Santos, J.M.; Kudling, T.V.; Clubb, J.H.A.; Haybout, L.; Arias, V.; et al. Boosting cytotoxicity of adoptive allogeneic NK cell therapy with an oncolytic adenovirus encoding a human vIL-2 cytokine for the treatment of human ovarian cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2023, 30, 1679–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Zhao, X.; Nie, X. Enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of NK cells in the treatment of ovarian cancer (Review). Oncol. Rep. 2024, 51, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, M.A.; Cooley, S.; Judson, P.L.; Ghebre, R.; Carson, L.F.; Argenta, P.A.; Jonson, A.L.; Panoskaltsis-Mortari, A.; Curtsinger, J.; McKenna, D.; et al. A phase II study of allogeneic natural killer cell therapy to treat patients with recurrent ovarian and breast cancer. Cytotherapy 2011, 13, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogstad-van Evert, J.; Bekkers, R.; Ottevanger, N.; Schaap, N.; Hobo, W.; Jansen, J.H.; Massuger, L.; Dolstra, H. Intraperitoneal infusion of ex vivo-cultured allogeneic NK cells in recurrent ovarian carcinoma patients (a phase I study). Medicine 2019, 98, e14290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evert, J.S.H.; de Jonge, P.; Zusterzeel, P.L.M.; Hobo, W.; van der Waart, A.B.; Fredrix, H.; Janssen, L.; Wuts, M.; Bosmans, L.; Spijkers, E.; et al. Intraperitoneal infusion of stem cell-derived natural killer cells in recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer patients: Results of the phase 1 INTRO-01 trial. Gynecol. Oncol. 2025, 204, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Wang, J.; Dasari, S.; Pepin, D.; Nephew, K.P.; Zamarin, D.; Mitra, A.K. Cancer associated fibroblasts serve as an ovarian cancer stem cell niche through noncanonical Wnt5a signaling. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.; Ding, B.; Dai, Z.; Yin, H.; Ding, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, K.; Lin, H.; Xiao, Z.; Shen, Y. Cancer-associated fibroblast-secreted FGF7 as an ovarian cancer progression promoter. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trub, M.; Uhlenbrock, F.; Claus, C.; Herzig, P.; Thelen, M.; Karanikas, V.; Bacac, M.; Amann, M.; Albrecht, R.; Ferrara-Koller, C.; et al. Fibroblast activation protein-targeted-4-1BB ligand agonist amplifies effector functions of intratumoral T cells in human cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melero, I.; Tanos, T.; Bustamante, M.; Sanmamed, M.F.; Calvo, E.; Moreno, I.; Moreno, V.; Hernandez, T.; Martinez Garcia, M.; Rodriguez-Vida, A.; et al. A first-in-human study of the fibroblast activation protein-targeted, 4-1BB agonist RO7122290 in patients with advanced solid tumors. Sci. Transl. Med. 2023, 15, eabp9229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Jing, X.; Wang, Y.; Jia, X.; Yang, X.; Chen, K. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts: Heterogeneity, Cancer Pathogenesis, and Therapeutic Targets. MedComm 2025, 6, e70292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupert, J.; Daquinag, A.; Yu, Y.; Dai, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Kolonin, M.G. Depletion of Adipose Stroma-Like Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Potentiates Pancreatic Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancer Res. Commun. 2025, 5, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| HGSOC (n = 306) [29] | HGSOC (n = 42) [108] | HGSOC (n = 133) [106] | LGSOC (n = 119) [107] | MOC (n = 9) [106] | MOC (n = 31) [31] | CCC (n = 24) [106] | SCST (n = 19) [106] | GCT (n = 46) [106] | SCCOHT (n = 12) [97] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP53 | 96% | 98% | 98% | 2% | 89% | 52% | 4% | 54% | ||

| Myc | 31% | 11% | 7% | 0% | 8% | |||||

| PIK3CA | 18% | 4% | 9% | <1% | 22% | 50% | ||||

| SOX2 | 15% | 0% | 4% | 0% | ||||||

| BRCA1 | 12% | 7% | 2% | 0% | ||||||

| BRCA2 | 12% | 13% | 1% | <1% | ||||||

| NF1 | 12% | 2% | 6% | 2% | ||||||

| KRAS | 11% | 11% | 5% | 32% | 67% | 45% | 8% | 28% | ||

| SMARCA4 | 11% | 4% | <1% | 8% | 92% | |||||

| AKT1 | 3% | 0% | <1% | 0% | ||||||

| PTEN | 8% | 4% | 7% | 0% | 11% | |||||

| CHD4 | 8% | ─ | ─ | |||||||

| BRAF | 7% | 0% | 9% | 23% | ||||||

| FOXL2 | 5% | 0% | 0% | 68% | ||||||

| ARID1A | 2% | 4% | 7% | <1% | 3% | 83% | ||||

| CTNNB1 | 2% | 2% | 0% | 4% | 16% | |||||

| APC | 4% | 0% | ||||||||

| POLE | 2% | 0% | 0% | 4% | ||||||

| DICER1 | 3% | 0% | 0% | <1% | ||||||

| BCOR | <1% | 7% | 4% | <1% | 4% |

| Types | NCT Number | Phase | Title | Status | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC-based therapy | NCT00799110 | 2 | Vaccination of Patients with Ovarian Cancer with Dendritic Cell/Tumor Fusions with Granulocyte Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF) and Imiquimod | ACTIVE_ NOT_RECRUITING | |

| NCT04834544 | 2 | A Study of Maintenance DCVAC/OvCa After First-Line Chemotherapy Added Standard of Care | RECRUITING | ||

| NCT04739527 | 1 | Phase 1 Study to Evaluate the Safety, Feasibility and Immunogenicity of an Allogeneic, Cell-Based Vaccine (DCP-001) in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer Patients After Primary Treatment | ACTIVE_ NOT_RECRUITING | [142] | |

| NCT05773859 | 1/2 | NEOadjuvant Dendritic Cell Vaccination for Ovarian Cancer | RECRUITING | [143] | |

| NCT05920798 | 1/2 | Vaccine Therapy Plus Pembrolizumab in Treating Advanced Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, or Primary Peritoneal Cavity Cancer | RECRUITING | ||

| NCT05964361 | 1/2 | First-in-Human Interleukin-15-Transpresenting Wilms’ Tumor Protein 1-Targeting Autologous Dendritic Cell Vaccination in Cancer Patients | ACTIVE_ NOT_RECRUITING | ||

| NCT06639074 | 2 | Folate Receptor Alpha Dendritic Cells or Placebo for the Treatment of Patients with Stage III or IV Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, or Primary Peritoneal Cancer, FAROUT Trial | RECRUITING | ||

| Macrophage-based therapy | NCT01113112 | - | Biobehavioral–Cytokine Interactions in Ovarian Cancer | ACTIVE_ NOT_RECRUITING | |

| NCT04660929 | 1 | CAR-Macrophages for the Treatment of HER2 Overexpressing Solid Tumors | ACTIVE_ NOT_RECRUITING | [144] | |

| NCT05053750 | Early_ 1 | TAME: A Pilot Study of Weekly Paclitaxel, Bevacizumab, and Tumor Associated Macrophage Targeted Therapy (Zoledronic Acid) in Women with Recurrent, Platinum-Resistant, Epithelial Ovarian, Fallopian Tube or Primary Peritoneal Cancer | ACTIVE_ NOT_RECRUITING | ||

| NCT05467670 | 2 | Safety and Efficacy of Anti-CD47, ALX148 in Combination with Liposomal Doxorubicin and Pembrolizumab in Recurrent Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer | RECRUITING | ||

| NCT06562647 | N.A. | SY001 Targets Mesothelin in a Single-Arm, Dose-Increasing Setting in Subjects with Advanced Solid Tumors | RECRUITING | [145] | |

| NCT06887673 | Early_ 1 | Lipid Mediators and Cancer: Montelukast, SPM, and Almonds | NOT_YET_RECRUITING | ||

| NK cell-based therapy | NCT02487693 | 2 | Radiofrequency Ablation Combined with Cytokine-Induced Killer Cells for the Patients with Ovarian Carcinoma | ACTIVE_ NOT_RECRUITING | |

| NCT05410717 | 1 | CLDN6/GPC3/Mesothelin/AXL-CAR-NK Cell Therapy for Advanced Solid Tumors | RECRUITING | [146] | |

| NCT05922930 | 1/2 | Study of TROP2 CAR Engineered IL15-Transduced Cord Blood-derived NK Cells Delivered Intraperitoneally for the Management of Platinum Resistant Ovarian Cancer, Mesonephric-Like Adenocarcinoma, and Pancreatic Cancer | RECRUITING | [147] | |

| NCT06395844 | 1/2 | Safety and Efficacy of Intraperitoneal Injection of METR-NK Cells as Neoadjuvant Therapy for Advanced Epithelial Ovarian Cancer | RECRUITING | ||

| NCT06342986 | 1 | Intraperitoneal FT536 in Recurrent Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancer | RECRUITING | ||

| NCT05856643 | Early_ 1 | Single-Arm, Open-Label Clinical Study of SZ011 in the Treatment of Ovarian Epithelial Carcinoma | RECRUITING | ||

| NCT06321484 | 1 | Intraperitoneal Cytokine-Induced Memory-Like (CIML) Natural Killer (NK) Cells in Recurrent Ovarian Cancer | RECRUITING | ||

| NCT06884345 | 1/2 | METR-NK Cells in Combination with Anti-Angiogenic Neoadjuvant Therapy for Advanced Epithelial Ovarian Cancer | ACTIVE_ NOT_RECRUITING | ||

| NCT07096583 | 1/2 | An Exploratory Study on NK Cell-Assisted Prevention of Bone Marrow Suppression During Chemotherapy for Ovarian Cancer | ACTIVE_ NOT_RECRUITING |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hong, S.Y.; Cho, A.; Chae, C.-S.; You, H.J. Targeting Ovarian Neoplasms: Subtypes and Therapeutic Options. Medicina 2025, 61, 2246. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122246

Hong SY, Cho A, Chae C-S, You HJ. Targeting Ovarian Neoplasms: Subtypes and Therapeutic Options. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2246. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122246

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Seon Young, Ahyoung Cho, Chang-Suk Chae, and Hye Jin You. 2025. "Targeting Ovarian Neoplasms: Subtypes and Therapeutic Options" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2246. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122246

APA StyleHong, S. Y., Cho, A., Chae, C.-S., & You, H. J. (2025). Targeting Ovarian Neoplasms: Subtypes and Therapeutic Options. Medicina, 61(12), 2246. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122246