Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Pharmacological Interventions for IgA Nephropathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Reporting Guidelines

2.2. Search Strategy and Information Sources

2.3. Study Selection and Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction and Management

2.5. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

2.6. Statistical Analysis and Data Synthesis

2.7. Projection of Hard Outcomes for Novel Therapeutic Agents

3. Results

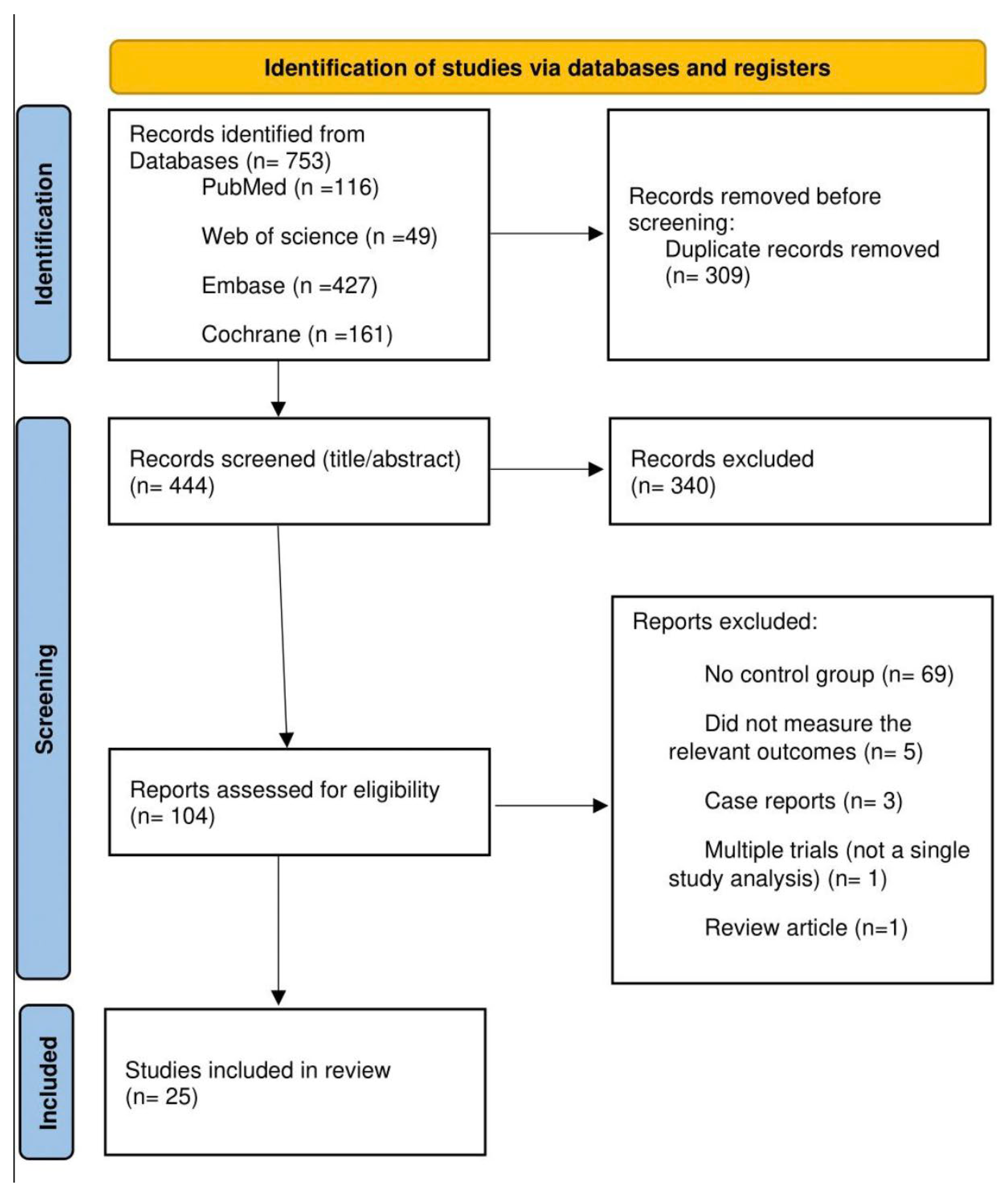

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

3.2. Effects on Proteinuria

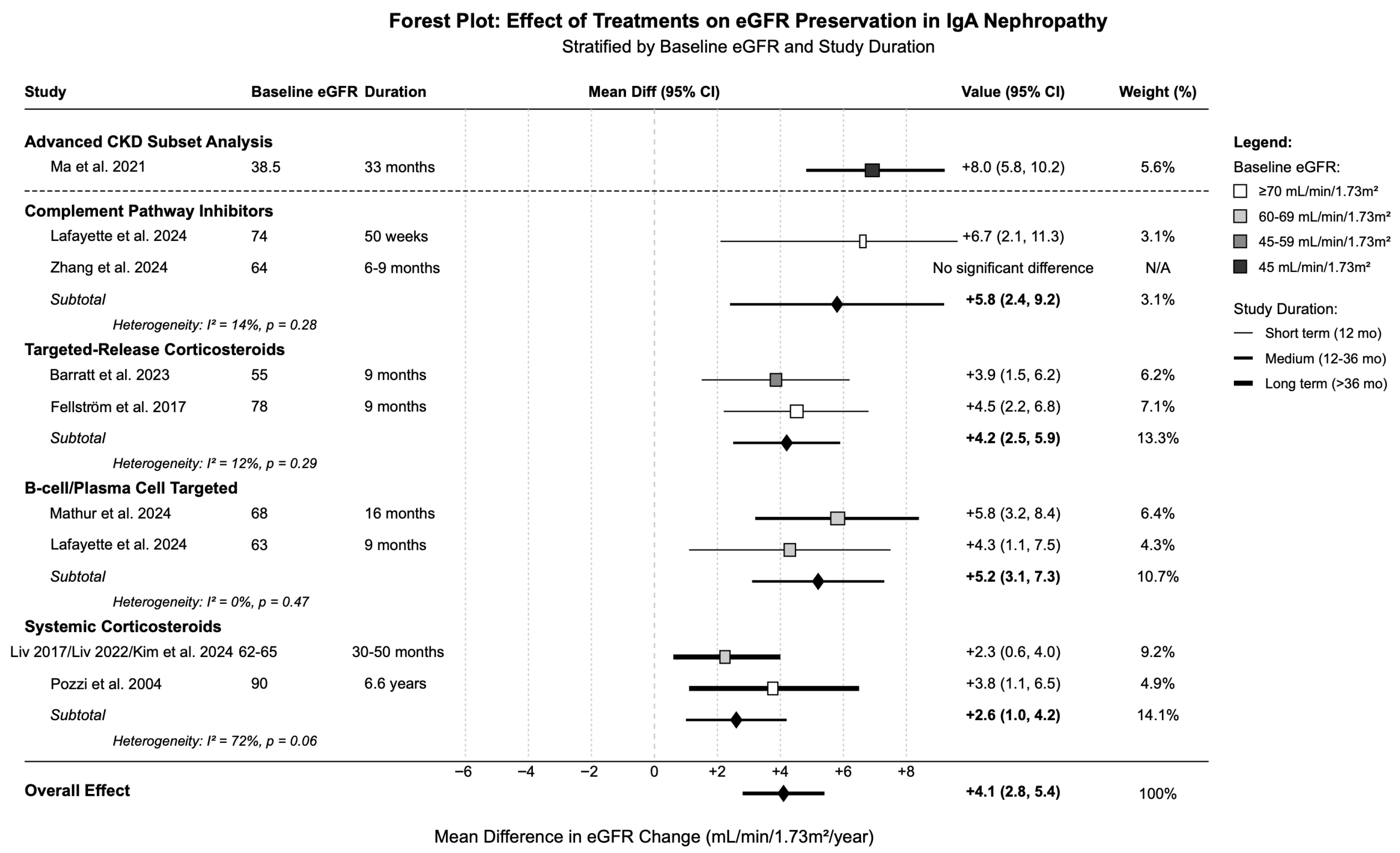

3.3. Effects on eGFR Preservation

3.4. Hard Kidney Outcomes

3.5. Safety Outcomes

3.6. Meta-Regression

3.7. Integrated Risk–Benefit Assessment

3.8. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.9. Publication Bias and Sensitivity Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rout, P.; Limaiem, F.; Hashmi, M.F. IgA Nephropathy (Berger Disease). In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Petrou, D.; Kalogeropoulos, P.; Liapis, G.; Lionaki, S. IgA Nephropathy: Current Treatment and New Insights. Antibodies 2023, 12, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.K.; Alexander, S.; Reich, H.N.; Selvaskandan, H.; Zhang, H.; Barratt, J. The pathogenesis of IgA nephropathy and implications for treatment. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2025, 21, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, A.M.; Hashmi, M.F. Glomerulonephritis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Cheng, T.; Liu, C.; Zhu, T.; Guo, C.; Li, S.; Rao, X.; Li, J. IgA Nephropathy: Current Understanding and Perspectives on Pathogenesis and Targeted Treatment. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.; Li, X.K. The Role of Immune Modulation in Pathogenesis of IgA Nephropathy. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natale, P.; Palmer, S.C.; Ruospo, M.; Saglimbene, V.M.; Craig, J.C.; Vecchio, M.; Samuels, J.A.; Molony, D.A.; Schena, F.P.; Strippoli, G.F. Immunosuppressive agents for treating IgA nephropathy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 3, Cd003965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppo, R. Treatment of IgA nephropathy: Recent advances and prospects. Nephrol. Ther. 2018, 14, S13–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, R.S.; Yeo, S.C.; Barratt, J.; Rizk, D.V. An Update on Current Therapeutic Options in IgA Nephropathy. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.K.; Barratt, J. The Rapidly Changing Treatment Landscape of IgA Nephropathy. Semin. Nephrol. 2024, 44, 151573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesař, V.; Radhakrishnan, J.; Charu, V.; Barratt, J. Challenges in IgA Nephropathy Management: An Era of Complement Inhibition. Kidney Int. Rep. 2023, 8, 1730–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassock, R.J. An Expert Opinion on Current and Future Treatment Approaches in IgA Nephropathy. Adv. Ther. 2025, 42, 2545–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippone, E.J.; Gulati, R.; Farber, J.L. The road ahead: Emerging therapies for primary IgA nephropathy. Front. Nephrol. 2025, 5, 1545329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarpioni, R.; Valsania, T. IgA Nephropathy: What Is New in Treatment Options? Kidney Dial. 2024, 4, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.; Carroll, K.; A. Inker, L.; Floege, J.; Perkovic, V.; Boyer-Suavet, S.; W. Major, R.; I. Schimpf, J.; Barratt, J.; Cattran, D.C.; et al. Proteinuria Reduction as a Surrogate End Point in Trials of IgA Nephropathy. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. CJASN 2019, 14, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleeson, P.J.; O’Shaughnessy, M.M.; Barratt, J. IgA nephropathy in adults-treatment standard. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. Off. Publ. Eur. Dial. Transpl. Assoc.—Eur. Ren. Assoc. 2023, 38, 2464–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunnicliffe, D.J.; Reid, S.; Craig, J.C.; Samuels, J.A.; Molony, D.A.; Strippoli, G.F. Non-immunosuppressive treatment for IgA nephropathy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 2, Cd003962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Rev. Esp. de Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkovic, V.; Barratt, J.; Rovin, B.; Kashihara, N.; Maes, B.; Zhang, H.; Trimarchi, H.; Kollins, D.; Papachristofi, O.; Jacinto-Sanders, S.; et al. Alternative Complement Pathway Inhibition with Iptacopan in IgA Nephropathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Rizk, D.V.; Perkovic, V.; Maes, B.; Kashihara, N.; Rovin, B.; Trimarchi, H.; Sprangers, B.; Meier, M.; Kollins, D.; et al. Results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled Phase 2 study propose iptacopan as an alternative complement pathway inhibitor for IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafayette, R.; Tumlin, J.; Fenoglio, R.; Kaufeld, J.; Pérez Valdivia, M.; Wu, M.S.; Susan Huang, S.H.; Alamartine, E.; Kim, S.G.; Yee, M.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Ravulizumab in IgA Nephropathy: A Phase 2 Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 2025, 36, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, J.; Lafayette, R.; Kristensen, J.; Stone, A.; Cattran, D.; Floege, J.; Tesar, V.; Trimarchi, H.; Zhang, H.; Eren, N.; et al. Results from part A of the multi-center, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled NefIgArd trial, which evaluated targeted-release formulation of budesonide for the treatment of primary immunoglobulin A nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2023, 103, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellström, B.C.; Barratt, J.; Cook, H.; Coppo, R.; Feehally, J.; de Fijter, J.W.; Floege, J.; Hetzel, G.; Jardine, A.G.; Locatelli, F.; et al. Targeted-release budesonide versus placebo in patients with IgA nephropathy (NEFIGAN): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 2117–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, M.; Barratt, J.; Chacko, B.; Chan, T.M.; Kooienga, L.; Oh, K.H.; Sahay, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Wong, M.G.; Yarbrough, J.; et al. A Phase 2 Trial of Sibeprenlimab in Patients with IgA Nephropathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafayette, R.; Barbour, S.; Israni, R.; Wei, X.; Eren, N.; Floege, J.; Jha, V.; Kim, S.G.; Maes, B.; Phoon, R.K.S.; et al. A phase 2b, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of atacicept for treatment of IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, 1306–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, J.; Liu, L.; Hao, C.; Li, G.; Fu, P.; Xing, G.; Zheng, H.; Chen, N.; Wang, C.; Luo, P.; et al. Randomized Phase 2 Trial of Telitacicept in Patients With IgA Nephropathy With Persistent Proteinuria. Kidney Int. Rep. 2023, 8, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lv, J.; Hladunewich, M.; Jha, V.; Hooi, L.S.; Monaghan, H.; Shan, S.; Reich, H.N.; Barbour, S.; Billot, L.; et al. The Efficacy and Safety of Reduced-Dose Oral Methylprednisolone in High-Risk Immunoglobulin A Nephropathy. Kidney Int. Rep. 2024, 9, 2168–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Wong, M.G.; Hladunewich, M.A.; Jha, V.; Hooi, L.S.; Monaghan, H.; Zhao, M.; Barbour, S.; Jardine, M.J.; Reich, H.N.; et al. Effect of Oral Methylprednisolone on Decline in Kidney Function or Kidney Failure in Patients With IgA Nephropathy: The TESTING Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2022, 327, 1888–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Zhang, H.; Wong, M.G.; Jardine, M.J.; Hladunewich, M.; Jha, V.; Monaghan, H.; Zhao, M.; Barbour, S.; Reich, H.; et al. Effect of Oral Methylprednisolone on Clinical Outcomes in Patients With IgA Nephropathy: The TESTING Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017, 318, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, C.; Andrulli, S.; Del Vecchio, L.; Melis, P.; Fogazzi, G.B.; Altieri, P.; Ponticelli, C.; Locatelli, F. Corticosteroid effectiveness in IgA nephropathy: Long-term results of a randomized, controlled trial. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 2004, 15, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, C.; Bolasco, P.G.; Fogazzi, G.B.; Andrulli, S.; Altieri, P.; Ponticelli, C.; Locatelli, F. Corticosteroids in IgA nephropathy: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 1999, 353, 883–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Z.; Chen, P.; Liu, L.J.; Cai, Q.Q.; Shi, S.F.; Chen, Y.Q.; Lv, J.C.; Zhang, H. Comparison of the effects of hydroxychloroquine and corticosteroid treatment on proteinuria in IgA nephropathy: A case-control study. BMC Nephrol. 2019, 20, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.J.; Yang, Y.Z.; Shi, S.F.; Bao, Y.F.; Yang, C.; Zhu, S.N.; Sui, G.L.; Chen, Y.Q.; Lv, J.C.; Zhang, H. Effects of Hydroxychloroquine on Proteinuria in IgA Nephropathy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2019, 74, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manno, C.; Torres, D.D.; Rossini, M.; Pesce, F.; Schena, F.P. Randomized controlled clinical trial of corticosteroids plus ACE-inhibitors with long-term follow-up in proteinuric IgA nephropathy. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009, 24, 3694–3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, G.; Jiang, L.; Singh, A.K.; Wang, H. Combination therapy of prednisone and ACE inhibitor versus ACE-inhibitor therapy alone in patients with IgA nephropathy: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2009, 53, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.C.; Chin, H.J.; Koo, H.S.; Kim, S. Tacrolimus decreases albuminuria in patients with IgA nephropathy and normal blood pressure: A double-blind randomized controlled trial of efficacy of tacrolimus on IgA nephropathy. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, R.J.; Bay, R.C.; Jennette, J.C.; Sibley, R.; Kumar, S.; Fervenza, F.C.; Appel, G.; Cattran, D.; Fischer, D.; Hurley, R.M.; et al. Randomized controlled trial of mycophenolate mofetil in children, adolescents, and adults with IgA nephropathy. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2015, 66, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, G.; Lin, J.; Rosenstock, J.; Markowitz, G.; D’Agati, V.; Radhakrishnan, J.; Preddie, D.; Crew, J.; Valeri, A.; Appel, G. Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) vs placebo in patients with moderately advanced IgA nephropathy: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2005, 20, 2139–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, B.D.; Oyen, R.; Claes, K.; Evenepoel, P.; Kuypers, D.; Vanwalleghem, J.; Van Damme, B.; Vanrenterghem, Y.F. Mycophenolate mofetil in IgA nephropathy: Results of a 3-year prospective placebo-controlled randomized study. Kidney Int. 2004, 65, 1842–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauen, T.; Wied, S.; Fitzner, C.; Eitner, F.; Sommerer, C.; Zeier, M.; Otte, B.; Panzer, U.; Budde, K.; Benck, U.; et al. After ten years of follow-up, no difference between supportive care plus immunosuppression and supportive care alone in IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2020, 98, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Yang, X.; Zhou, M.; Bai, M.; Zhao, L.; Li, L.; Dong, R.; Liu, C.; Li, R.; Sun, S. Treatment for IgA nephropathy with stage 3 or 4 chronic kidney disease: Low-dose corticosteroids combined with oral cyclophosphamide. J. Nephrol. 2020, 33, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauen, T.; Fitzner, C.; Eitner, F.; Sommerer, C.; Zeier, M.; Otte, B.; Panzer, U.; Peters, H.; Benck, U.; Mertens, P.R.; et al. Effects of Two Immunosuppressive Treatment Protocols for IgA Nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.H.; Lee, J.E.; Park, J.H.; Lim, S.; Jang, H.R.; Kwon, G.Y.; Huh, W.; Jung, S.H.; Kim, Y.G.; Oh, H.Y.; et al. The effects of cytotoxic therapy in progressive IgA nephropathy. Ann. Med. 2016, 48, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buse, M.; Dounousi, E.; Kramann, R.; Floege, J.; Stamellou, E. Newer B-cell and plasma-cell targeted treatments for rituximab-resistant patients with membranous nephropathy. Clin. Kidney J. 2025, 18, sfaf088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, K.; Clauder, A.K.; Manz, R.A. Targeting B Cells and Plasma Cells in Autoimmune Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haselmayer, P.; Camps, M.; Liu-Bujalski, L.; Nguyen, N.; Morandi, F.; Head, J.; O’Mahony, A.; Zimmerli, S.C.; Bruns, L.; Bender, A.T.; et al. Efficacy and Pharmacodynamic Modeling of the BTK Inhibitor Evobrutinib in Autoimmune Disease Models. J. Immunol. 2019, 202, 2888–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nester, C.M.; Eisenberger, U.; Karras, A.; le Quintrec, M.; Lightstone, L.; Praga, M.; Remuzzi, G.; Soler, M.J.; Liu, J.; Meier, M.; et al. Iptacopan Reduces Proteinuria and Stabilizes Kidney Function in C3 Glomerulopathy. Kidney Int. Rep. 2025, 10, 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, S.J.; Zhang, Y.; Smith, R.J.H. Acquired drivers of C3 glomerulopathy. Clin. Kidney J. 2025, 18, sfaf022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.K.; Dormer, J.P.; Barratt, J. The role of complement in glomerulonephritis—Are novel therapies ready for prime time? Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2022, 38, 1789–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, E.; Cortinovis, M.; Remuzzi, G. Kidney diseases. Immunol. Rev. 2023, 313, 239–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriilaki, E.; Anagnostopoulos, A.; Mastellos, D.C. Complement in Thrombotic Microangiopathies: Unraveling Ariadne’s Thread Into the Labyrinth of Complement Therapeutics. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitcher, D.; Braddon, F.; Hendry, B.; Mercer, A.; Osmaston, K.; Saleem, M.A.; Steenkamp, R.; Wong, K.; Turner, A.N.; Wang, K.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes in IgA Nephropathy. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. CJASN 2023, 18, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inker, L.A.; Heerspink, H.J.L.; Tighiouart, H.; Chaudhari, J.; Miao, S.; Diva, U.; Mercer, A.; Appel, G.B.; Donadio, J.V.; Floege, J.; et al. Association of Treatment Effects on Early Change in Urine Protein and Treatment Effects on GFR Slope in IgA Nephropathy: An Individual Participant Meta-analysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. Off. J. Natl. Kidney Found. 2021, 78, 340–349.e341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, W.G.; Staplin, N.; Haynes, R. Kidney disease trials for the 21st century: Innovations in design and conduct. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesar, V.; Barratt, J. Proceedings of 16th International Symposium on IgA Nephropathy. Kidney Dis. 2021, 7, 1–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Rivera, J.; Fervenza, F.C.; Ortiz, A. Recent Clinical Trials Insights into the Treatment of Primary Membranous Nephropathy. Drugs 2022, 82, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, L.; Costa, B.; Pereira, M.; Silva, A.; Santos, J.; Saldanha, L.; Silva, I.; Magalhães, P.; Schmidt, S.; Vale, N. Advancing Precision Medicine: A Review of Innovative In Silico Approaches for Drug Development, Clinical Pharmacology and Personalized Healthcare. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, G.; Bitew, M. Revolutionizing Personalized Medicine: Synergy with Multi-Omics Data Generation, Main Hurdles, and Future Perspectives. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppelaars, F.; Faria, B.; Schwaeble, W.; Daha, M.R. The Contribution of Complement to the Pathogenesis of IgA Nephropathy: Are Complement-Targeted Therapies Moving from Rare Disorders to More Common Diseases? J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Treatment Category | Study Design | n | Intervention | Comparator | Follow-Up Duration | Primary Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perkovic et al. 2025 [19] | Complement Pathway Inhibitor | RCT, Phase 3 (APPLAUSE-IgAN) | 443 | Iptacopan 200 mg PO BID | Placebo PO BID | Interim 9 mo (full 24 mo) | % change in 24 h UPCR |

| Zhang et al. 2024 [20] | RCT, Phase 2 (Adaptive design) | 112 | Iptacopan 10–200 mg PO BID | Placebo PO BID | 3–6 mo + 3 mo follow-up | Dose–response on 24 h UPCR | |

| Lafayette et al. 2025 (SANCTUARY) [21] | RCT, Phase 2 (SANCTUARY) | 66 | Ravulizumab IV Q8 W | Placebo IV Q8 W | 50 wks | % change in 24 h UPE at wk 26 | |

| Barratt et al. 2023 [22] | Targeted-Release Corticosteroid | RCT, Phase 3 (NefIgArd Part A) | 199 | Nefecon 16 mg PO QD | Placebo PO QD | 12 mo (9 mo Rx + 3 mo) | Change in 24 h UPCR at 9 mo |

| Fellström et al. 2017 [23] | RCT, Phase 2b (NEFIGAN) | 149 | Nefecon 16 mg or 8 mg PO QD | Placebo PO QD | 12 mo (9 mo Rx + 3 mo) | Mean change in UPCR over 9 mo | |

| Mathur et al. 2024 [24] | B-cell/Plasma Cell Targeted | RCT, Phase 2 (ENVISION) | 155 | Sibeprenlimab IV 2–8 mg/kg monthly | Placebo IV monthly | 16 mo median | % change in log UPCR at 12 mo |

| Lafayette et al. 2024 (ORIGIN) [25] | RCT, Phase 2b (ORIGIN) | 116 | Atacicept SC 25–150 mg weekly | Placebo SC weekly | 36 wks | % change in 24 h UPCR at 24 wks | |

| Lv et al. 2023 [26] | RCT, Phase 2 (Telitacicept) | 44 | Telitacicept SC 160–240 mg weekly | Placebo SC weekly | 24 wks + 28 d follow-up | Change in 24 h proteinuria at wk 24 | |

| Kim et al. 2024 [27] | Systemic Corticosteroid | RCT, Phase 3 (Reduced-dose TESTING) | 241 | Methylprednisolone 0.4 mg/kg/d reduced | Placebo | Median 2.5 yrs | Composite: 40% eGFR decline/ESKD/death |

| Lv et al. 2022 [28] | RCT, Phase 2/3 (TESTING) | 503 | Methylprednisolone 0.4–0.8 mg/kg/d | Placebo | Median 4.2 yrs | Composite: 40% eGFR decline/ESKD/death | |

| Lv et al. 2017 [29] | RCT, Phase 2/3 (TESTING stopped early) | 262 | Methylprednisolone 0.6–0.8 mg/kg/d full | Placebo | Median 2.1 yrs | Composite: 40% eGFR decline/ESKD/death | |

| Pozzi et al. 2004 [30] | RCT Long-term Follow-up | 86 | IV Methylpred + Oral Prednisone | Supportive Care | Median 6.6 yrs (Max 10 yrs) | Doubling of Scr | |

| Pozzi et al. 1999 [31] | RCT | 86 | IV Methylpred + Oral Prednisone | Supportive Care | Median 4 yrs (Range 1–10 yrs) | 50–100% increase in Scr | |

| Yang et al. 2019 [32] | Antimalarial | Case–Control (PS Matched) | 184 | Hydroxychloroquine 200–400 mg/d | Corticosteroids | 6 mo | % change in proteinuria at 6 mo |

| Liu et al. 2019 [33] | RCT, Phase 2 | 60 | Hydroxychloroquine 200–400 mg/d PO | Placebo PO | 6 mo | % change in 24 h UPE at 6 mo | |

| Manno et al. 2009 [34] | Systemic Corticosteroid + ACEi | RCT Long-term Follow-up | 97 | Prednisone 1 mg/kg + Ramipril | Ramipril alone | Median 5 yrs (Range 3–9 yrs) | Composite: Scr doubling or ESKD |

| Lv et al. 2009 [35] | RCT | 63 | Prednisone 0.8–1.0 mg/kg + Cilazapril | Cilazapril alone | Mean 27 mo (Range 15–48 mo) | Kidney survival (50% Scr increase) | |

| Kim et al. 2013 [36] | Calcineurin Inhibitor | RCT | 40 | Tacrolimus target 5–10 ng/mL | Placebo | 16 wks | % change in UACR (wk 12 and 16 avg) |

| Hogg et al. 2015 [37] | Antimetabolite | RCT | 52 | MMF 25–36 mg/kg/d + lisinopril/losartan | Placebo + lisinopril/losartan | 6–12 mo Rx + 12 mo follow-up | Change in UPCR at 6 and 12 mo |

| Frisch et al. 2005 [38] | RCT | 32 | MMF 1000 mg PO BID | Placebo PO BID | 2 yrs total | Sustained 50% increase in Scr | |

| Maes et al. 2004 [39] | RCT | 34 | MMF 1 g PO BID | Placebo PO BID | 3 yrs | ≥25% decrease in inulin clearance | |

| Rauen et al. 2020 [40] | Systemic Corticosteroid + Cytotoxic Agent | Retrospective (STOP-IgAN 10 yr) | 149 | Supportive Care + IS (Steroids ± CTX/AZA) | Supportive Care alone | Median 7.4 yrs (Range 0.3–10 yrs) | Composite: death/ESKD/>40% eGFR decline |

| Ma et al. 2020 [41] | Retrospective (PS Matched) | 132 | Low-dose CS + oral CTX | Supportive Care | Median 33 mo | ≥50% eGFR reduction or ESRD | |

| Rauen et al. 2018 [42] | Post hoc Subgroup (STOP-IgAN) | 162 | Supportive Care + IS (Steroids ± CTX/AZA) | Supportive Care alone | 3 yrs | Full remission; GFR loss ≥15 mL/min | |

| Shin et al. 2016 [43] | Cytotoxic Agent | Retrospective Cohort | 86 | CTX (oral/IV) ± AZA/MMF ± steroids | RAS blockers only | Median 39 mo | Renal survival (time to ESRD) |

| Treatment Category | Patients (n) | Mean Difference in Proteinuria Reduction (%) vs. Control [95% CI] * | Heterogeneity Assessment | Subgroup: Baseline Proteinuria > 1 g/g | Subgroup: Treatment Duration > 6 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complement Pathway Inhibitors | 621 | −31.2% [−38.1, −24.3] | Moderate (I2 = 43%) | −31.2% (all studies > 1 g/g) | −38.3% (Perkovic); −30.1% (Lafayette) |

| 555 | −32.5% [−43.8, −21.2] | Moderate | −32.5% (all > 1 g/g) | −38.3% (Perkovic) |

| 66 | −25.1% [−41.5, −8.7] | N/A | −25.1% (2.8 g/d) | N/A (6 months only) |

| Targeted-Release Corticosteroids | 382 | −30.9% [−37.8, −24.0] | Low (I2 = 15%) | −27.0% (Barratt 2023) [22] | −30.9% (all studies ≥ 9 months) |

| 382 | −30.9% [−37.8, −24.0] | Low (I2 = 15%) | −27.0% (Barratt 2023) [22] | −30.9% (all studies ≥ 9 months) |

| B-cell/Plasma Cell Targeted | 271 | −34.0% [−45.7, −22.3] | Moderate (I2 = 46%) | −34.0% (all studies > 1 g/g) | −33.7% (Mathur) |

| 155 | −39.0% [−48.3, −29.7] | N/A | −39.0% (1.7 g/g) | −39.0% (12 months) |

| 116 | −25.0% [−39.1, −10.9] | N/A | −25.0% (1.6 g/g) | N/A (≤6 months) |

| 44 | −38.0% [−63.8, −12.2] | N/A | −38.0% (1.7 g/d) | N/A (6 months) |

| Systemic Corticosteroids | 1360 | −25.5% [−35.0, −16.0] | Substantial (I2 = 68%) | −25.5% (all studies > 1 g/g) | −25.5% (all studies > 6 months) |

| Antimalarials | 244 | −21.9% [−68.4, 24.6] | Considerable (I2 = 94%) | −21.9% (all studies > 1 g/g) | −21.9% (all studies = 6 months) |

| 60 | −58.4% [−73.5, −43.3] | N/A | −58.4% (1.7 g/d) | N/A (6 months) |

| 184 | +14.4% [4.2, 24.6] | N/A | +14.4% (1.75 g/d) | N/A (6 months) |

| Systemic Corticosteroids + ACEi | 180 | −35.0% [−48.4, −21.6] | Low (I2 = 10%) | −35.0% (all studies > 1 g/g) | −35.0% (all studies > 6 months) |

| Calcineurin Inhibitor | 40 | −34.7% [−52.0, −17.4] | N/A | −34.7% (1.0 g/g) | N/A (4 months) |

| Antimetabolites | 66 | −6.0% [−25.6, 13.6] | Low (I2 = 0%) | −6.0% (all studies > 1 g/g) | −6.0% (all studies > 6 months) |

| Systemic Corticosteroid + Cytotoxic Agent | 218 | −28.9% [−44.5, −13.3] | Low (I2 = 22%) | −28.9% (all studies > 1 g/g) | −28.9% (all studies > 6 months) |

| Treatment Category | Patients (n) | Mean Difference in eGFR Change (mL/min/1.73 m2/year) vs. Control [95% CI] * | Heterogeneity Assessment | Subgroup: Baseline eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Subgroup: Follow-Up Duration >12 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complement Pathway Inhibitors | 221 | +5.8 [2.4, 9.2] | Low (I2 = 14%) | +6.7 (Lafayette-74 mL/min/1.73 m2) | Not available |

| 0† | Data pending (blinded) | N/A | Data pending | Data pending |

| 66 | +6.7 [2.1, 11.3] | N/A | +6.7 (74 mL/min/1.73 m2) | Not available (50 weeks) |

| 112 | No significant difference reported | N/A | No difference (64 mL/min/1.73 m2) | Not available (≤9 months) |

| Targeted-Release Corticosteroids | 382 | +4.2 [2.5, 5.9] | Low (I2 = 12%) | +4.3 (all studies baseline eGFR >55) | +4.2 (all 9–12 months) |

| 382 | +4.2 [2.5, 5.9] | Low (I2 = 12%) | +4.3 (all studies baseline eGFR >55) | +4.2 (all 9–12 months) |

| B-cell/Plasma Cell Targeted | 271 | +5.2 [3.1, 7.3] | No heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) | +5.2 (all studies baseline eGFR > 60) | +5.8 (Mathur-16 months) |

| 155 | +5.8 [3.2, 8.4] | N/A | +5.8 (68 mL/min/1.73 m2) | +5.8 (16 months) |

| 116 | +4.3 [1.1, 7.5] | N/A | +4.3 (63 mL/min/1.73 m2) | Not available (9 months) |

| Systemic Corticosteroids | 1092 | +2.6 [1.0, 4.2] | Substantial (I2 = 72%) | +1.9 (> 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) | +2.8 (>12 months) |

| 1006 | +2.3 [0.6, 4.0] | Substantial (I2 = 67%) | +1.5 (> 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) | +2.3 (>12 months) |

| 86 | +3.8 [1.1, 6.5] | N/A | +3.8 (90 mL/min) | +3.8 (median 6.6 years) |

| Antimalarials | 244 | +0.2 [−1.5, 1.9] | No heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) | +0.2 (all ~55 mL/min/1.73 m2) | Not available (all 6 months) |

| Systemic Corticosteroids + ACEi | 180 | +4.1 [2.2, 6.0] | Moderate (I2 = 35%) | +5.6 (>90 mL/min/1.73 m2) | +5.6 (>12 months) |

| 117 | +5.6 [3.3, 7.9] | No heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) | +5.6 (>90 mL/min/1.73 m2) | +5.6 (>12 months) |

| 63 | +2.3 [0.1, 4.5] | N/A | +2.3 (101 mL/min/1.73 m2) | +2.3 (mean 27 months) |

| Calcineurin Inhibitor | 40 | −2.2 [−4.8, 0.4] | N/A | −2.2 (82 mL/min/1.73 m2) | Not available (16 weeks) |

| Antimetabolites | 66 | −0.8 [−2.6, 1.0] | No heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) | −0.8 (>66 mL/min/1.73 m2) | −0.8 (all ≥24 months) |

| Systemic Corticosteroid + Cytotoxic Agent | 443 | +0.5 [−1.8, 2.8] | Considerable (I2 = 89%) | −0.3 (58 mL/min/1.73 m2) | +0.5 (all >12 months) |

| 311 | −0.3 [−2.8, 2.2] | No heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) | −0.3 (58 mL/min/1.73 m2) | −0.3 (>36 months) |

| 132 | +8.0 [5.8, 10.2] | N/A | +8.0 (38.5 mL/min/1.73 m2) | +8.0 (median 33 months) |

| Cytotoxic Agent | 86 | +4.4 [2.1, 6.7] | N/A | +4.4 (64 mL/min/1.73 m2) | +4.4 (median 39 months) |

| Treatment Category | Patients (Number) | Composite Kidney Outcome (HR or RR with 95% CI) | ESKD Alone (HR or RR with 95% CI) | eGFR Decline ≥ 40% (HR or RR with 95% CI) | Heterogeneity (I2 Statistic) | NNT ‡ [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic Corticosteroids | 1006 | HR 0.37 [0.26, 0.52] * | HR 0.37 [0.21, 0.65] * | HR 0.41 [0.25, 0.68] * | Low (I2 = 13%) | 8 [6, 13] |

| 241 | HR 0.24 [0.10, 0.58] | HR 0.26 [0.06, 1.05] | Not reported separately | N/A | 8 [6, 18] |

| 503 | HR 0.43 [0.25, 0.74] | HR 0.40 [0.20, 0.81] | Not reported separately | N/A | 10 [7, 24] |

| 262 | HR 0.37 [0.17, 0.85] | HR 0.40 [0.11, 1.48] | HR 0.41 [0.18, 0.94] | N/A | 10 [7, 33] |

| Complement Pathway Inhibitors | 0 § | Projected HR 0.42 [0.25, 0.70] * | Not available | Not available | N/A | Projected 9 [6, 18] * |

| Targeted-Release Corticosteroids | 0 § | Projected HR 0.45 [0.28, 0.73] * | Not available | Not available | N/A | Projected 10 [7, 20] * |

| B-cell/Plasma Cell Targeted | 0 § | Projected HR 0.38 [0.21, 0.67] * | Not available | Not available | N/A | Projected 8 [5, 17] * |

| Systemic Corticosteroids + ACEi | 183 | RR 0.19 [0.07, 0.51] * | RR 0.18 [0.05, 0.65] * | RR 0.23 [0.09, 0.59] | No heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) | 4 [3, 7] |

| 97 | RR 0.15 [0.04, 0.59] | RR 0.14 [0.03, 0.64] | Data not available | N/A | 4 [3, 8] |

| 86 | RR 0.23 [0.07, 0.77] | Data not available | RR 0.23 [0.09, 0.59] | N/A | 5 [3, 16] |

| Antimalarials | 0 § | Projected HR 0.62 [0.37, 1.05] * | Not available | Not available | N/A | Projected 14 [8, 40] * |

| 0 § | Projected HR 0.55 [0.30, 0.99] * | Not available | Not available | N/A | Projected 12 [7, 35] * |

| Systemic Corticosteroid + Cytotoxic Agent | 281 | HR 0.77 [0.46, 1.28] | HR 0.78 [0.38, 1.59] | HR 0.71 [0.35, 1.43] | Moderate (I2 = 44%) | Not significant |

| 149 | HR 1.20 [0.75, 1.92] | HR 0.90 [0.49, 1.74] | HR 1.62 [0.90, 2.92] | N/A | Not significant |

| 132 | HR 0.35 [0.18, 0.68] | Data not available | Data not available | N/A | 3 [2, 5] |

| Antimetabolites | 66 | RR 1.66 [0.63, 4.36] | RR 3.20 [0.66, 15.53] | RR 1.15 [0.52, 2.54] | No heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) | Not significant |

| Classic Pulse Steroid Regimen (Pozzi) | 86 | RR 0.42 [0.20, 0.88] | RR 0.37 [0.11, 1.25] | Not reported | N/A | 5 [3, 21] |

| Cytotoxic Agent | 86 | HR 0.13 [0.03, 0.66] | Data not available | Data not available | N/A | Not calculable |

| Calcineurin Inhibitor | 0 § | Projected HR 0.58 [0.32, 1.04] * | Not available | Not available | N/A | Projected 13 [7, 38] * |

| Treatment Category | Patients (n) | Serious Adverse Events (RR with 95% CI) * | Infections (RR with 95% CI) * | Serious Infections (RR with 95% CI)* | Withdrawal Due to AEs (RR with 95% CI) * | Treatment-Specific Adverse Events | Mortality (Events/Total) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complement Pathway Inhibitors | 621 | 1.31 [0.68, 2.51] | 0.97 [0.84, 1.13] | 0.58 [0.07, 5.01] | 2.09 [0.66, 6.59] | No meningococcal infections despite theoretical risk | 0/277 vs. 1/221 |

| 555 | 1.62 [0.83, 3.16] | 0.96 [0.83, 1.12] | Not reported | 2.09 [0.66, 6.59] | No meningococcal/encapsulated bacterial infections | 0/222 vs. 0/221 |

| 66 | 2.17 [0.09, 51.61] | 0.89 [0.72, 1.09] | Not reported | Not reported | One COVID-19 SAE (Ravulizumab arm) | 0/43 vs. 0/23 |

| Targeted-Release Corticosteroids | 382 | 1.77 [0.83, 3.74] | 1.10 [0.95, 1.27] | Not reported | 8.18 [1.92, 34.89] | Cushingoid features, acne, peripheral edema, muscle spasms | 0/196 vs. 0/152 |

| 382 | 1.77 [0.83, 3.74] | 1.10 [0.95, 1.27] | Not reported | 8.18 [1.92, 34.89] | Cushingoid features, acne, peripheral edema, muscle spasms | 0/196 vs. 0/152 |

| B-cell/Plasma Cell Targeted | 315 | 0.44 [0.15, 1.33] | 0.97 [0.89, 1.06] | Not reported | 1.10 [0.45, 2.64] | Injection site reactions (telitacicept), reduced immunoglobulin levels | 0/173 vs. 1/96 |

| 155 | 0.81 [0.20, 3.22] | 1.11 [0.90, 1.38] | Not reported | Not reported | No specific safety signals | 0/117 vs. 1/38 |

| 116 | 0.22 [0.04, 1.18] | 0.92 [0.77, 1.10] | Not reported | Not reported | Reduced immunoglobulin levels, generally above LLN | 0/82 vs. 0/34 |

| 44 | 1.43 [0.10, 19.83] | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Injection site reactions (63% vs. 0%) | 0/30 vs. 0/14 |

| Systemic Corticosteroids | 1360 | 3.28 [2.11, 5.09] | 1.20 [1.02, 1.41] | 5.61 [1.97, 15.94] | 3.21 [1.66, 6.21] | New-onset diabetes (0–2%), weight gain, mood effects | 4/751 vs. 1/609 |

| 262 | 4.59 [1.55, 13.63] | Not reported | Not reported (2 deaths) | Higher with steroids | Not specifically listed | 2/136 vs. 0/126 |

| 241 | 2.40 [0.63, 9.18] | 2.0 [0.37, 10.79] | 2.0 [0.37, 10.79] | Not reported | New onset diabetes: 2 (2%) vs. 0 | 1/121 vs. 0/120 |

| Antimalarials | 244 | 0.08 [0.00, 1.34] | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | No significant ophthalmologic events with HCQ | 0/122 vs. 1/122 |

| 60 | Not observed | Not reported | Not reported | None | No significant ophthalmologic events | 0/30 vs. 0/30 |

| 184 | 0.08 [0.00, 1.34] | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | None with HCQ vs. 6 SAEs (6.5%) with CS | 0/92 vs. 1/92 |

| Systemic Corticosteroids + ACEi | 180 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | None reported | Mild Cushingoid features, transient AEs (palpitations/arthralgia/insomnia) | 0/91 vs. 0/89 |

| Calcineurin Inhibitor | 40 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 1 patient stopped for weakness/myalgia | GI effects, headache, tremor, coldness, 1 new onset DM in Tac arm | 0/20 vs. 0/20 |

| Antimetabolites | 66 | Not reported | Not reported | 1 TB reactivation with MMF | 4 withdrawals (19%) | GI side effects, leukopenia, hemoglobin reduction | 0/38 vs. 1/28 |

| Systemic Corticosteroid + Cytotoxic Agent | 443 | 3.13 [1.49, 6.60] | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Infections, bone marrow suppression | 6/210 vs. 3/233 |

| 311 | 3.42 [1.54, 7.57] | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | More AEs with IS in both cohorts | 5/137 vs. 2/174 |

| 132 | 3.63 [0.42, 31.27] | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Hospitalization for infection: SC 2.4%, CS 9.1%, CS + CTX 8.7% | 0/69 vs. 0/41 |

| Treatment Category | Mean Proteinuria Reduction (%) | Projected/Observed Kidney Failure Risk Reduction | SAE Risk (RR) | Infection Risk (RR) | Estimated NNT § | Estimated NNH | Benefit-Risk Ratio | Patient Profiles Most Likely to Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complement Pathway Inhibitors | 31.2% [−38.1, −24.3] | Projected: HR 0.42 [0.25, 0.70] | 1.31 [0.68, 2.51] | 0.97 [0.84, 1.13] | 9 [6, 18] | 33 [12, ∞] | Favorable | High proteinuria (>1.5 g/g), preserved eGFR, high cardiovascular risk |

| Targeted-Release Corticosteroids | 30.9% [−37.8, −24.0] | Projected: HR 0.45 [0.28, 0.73] | 1.77 [0.83, 3.74] | 1.10 [0.95, 1.27] | 10 [7, 20] | 25 [14, ∞] | Favorable | Proteinuria >1 g/g, preserved eGFR, high risk for systemic steroid complications |

| B-cell/Plasma Cell Targeted | 34.0% [−45.7, −22.3] | Projected: HR 0.38 [0.21, 0.67] | 0.44 [0.15, 1.33] | 0.97 [0.89, 1.06] | 8 [5, 17] | No increased risk | Very favorable | High proteinuria, evidence of immune activation, preserved eGFR |

| Systemic Corticosteroids | 25.5% [−35.0, −16.0] | HR 0.37 [0.26, 0.52] | 3.28 [2.11, 5.09] | 1.20 [1.02, 1.41] | 8 [6, 13] | 11 [7, 22] | Moderately favorable | Proteinuria >1 g/d, eGFR >30 mL/min/1.73 m2, low infection risk, <60 years old |

| 22.0% [−31.2, −12.8] | HR 0.24 [0.10, 0.58] | 2.40 [0.63, 9.18] | 2.0 [0.37, 10.79] | 8 [6, 18] | 20 [10, ∞] | Favorable | Same as above; preferred over full dose |

| 28.0% [−38.5, −17.5] | HR 0.37 [0.17, 0.85] | 4.59 [1.55, 13.63] | Not reported | 10 [7, 33] | 7 [4, 15] | Less favorable | Only when reduced-dose inadequate; requires infection prophylaxis |

| Antimalarials | 21.9% [−68.4, 24.6] | Projected: HR 0.62 [0.37, 1.05] | 0.08 [0.00, 1.34] | Not reported | 14 [8, 40] | No increased risk | Favorable | Mild–moderate proteinuria, preserved eGFR, contraindications to immunosuppression |

| 58.4% [−73.5, −43.3] | Projected: HR 0.55 [0.30, 0.99] | Not observed | Not reported | 12 [7, 35] | No increased risk | Very favorable | Same as above |

| Systemic Corticosteroids + ACEi | 35.0% [−48.4, −21.6] | RR 0.19 [0.07, 0.51] | Not reported | Not reported | 4 [3, 7] | Unknown | Very favorable | Proteinuria >1 g/d, preserved eGFR (>60), low infection risk |

| Calcineurin Inhibitor | 34.7% [−52.0, −17.4] | Projected: HR 0.58 [0.32, 1.04] | Not reported | Not reported | 13 [7, 38] | Unknown | Uncertain | Asian patients, mild disease, short-term therapy |

| Antimetabolites | 6.0% [−25.6, 13.6] | RR 1.66 [0.63, 4.36] | Not reported | Not reported | Not significant | Unknown | Unfavorable | Not recommended as primary therapy for IgAN |

| Systemic Corticosteroid + Cytotoxic Agent | 28.9% [−44.5, −13.3] | HR 0.77 [0.46, 1.28] | 3.13 [1.49, 6.60] | Not reported | Not significant | 11 [6, 33] | Unfavorable | Generally not recommended except for rapidly progressive GN |

| Not directly compared | HR 0.35 [0.18, 0.68] | 3.63 [0.42, 31.27] | Not reported | 3 [2, 5] | Unknown | Uncertain | Advanced CKD (stage 3–4) with progressive disease |

| Classic Pulse Steroid Regimen (Pozzi) | ~30% (estimated) | RR 0.42 [0.20, 0.88] | Not reported | Not reported | 5 [3, 21] | Unknown | Favorable | Proteinuria >1 g/d, preserved eGFR, low infection risk |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alroshodi, A.; Al-Harbi, F.A.; Alkuwaiti, M.A.; Alabdulmohsen, D.M.; Mobarki, H.J.; AlShammari, R.F.; Alsharif, R.L.; Wasaya, H.I.; Alshehri, H.J.; Azzam, A.Y. Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Pharmacological Interventions for IgA Nephropathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina 2025, 61, 2233. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122233

Alroshodi A, Al-Harbi FA, Alkuwaiti MA, Alabdulmohsen DM, Mobarki HJ, AlShammari RF, Alsharif RL, Wasaya HI, Alshehri HJ, Azzam AY. Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Pharmacological Interventions for IgA Nephropathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2233. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122233

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlroshodi, Abdulaziz, Faisal A. Al-Harbi, Mohanad A. Alkuwaiti, Dalal M. Alabdulmohsen, Hanin J. Mobarki, Reem F. AlShammari, Rewa L. Alsharif, Hanan I. Wasaya, Hussam J. Alshehri, and Ahmed Y. Azzam. 2025. "Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Pharmacological Interventions for IgA Nephropathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2233. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122233

APA StyleAlroshodi, A., Al-Harbi, F. A., Alkuwaiti, M. A., Alabdulmohsen, D. M., Mobarki, H. J., AlShammari, R. F., Alsharif, R. L., Wasaya, H. I., Alshehri, H. J., & Azzam, A. Y. (2025). Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Pharmacological Interventions for IgA Nephropathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina, 61(12), 2233. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122233