Effect of Local Anesthetics on Experimental Postoperative Adhesion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Trial Sequential Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Literature Search

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Methodological Quality and Publication

2.7. Statistical Analyses

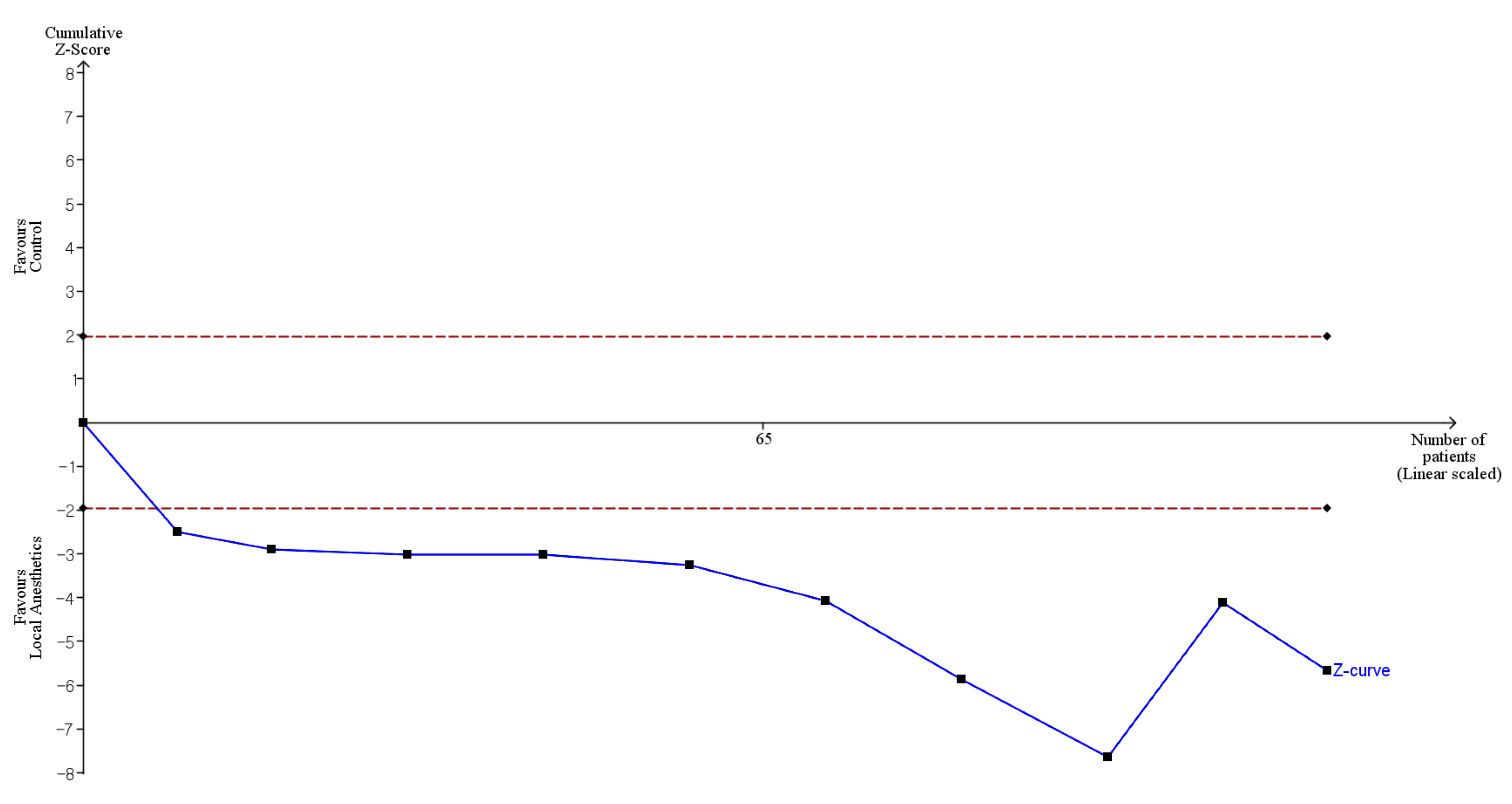

2.8. Trial Sequential Analysis

2.9. Certainty of Evidence

3. Results

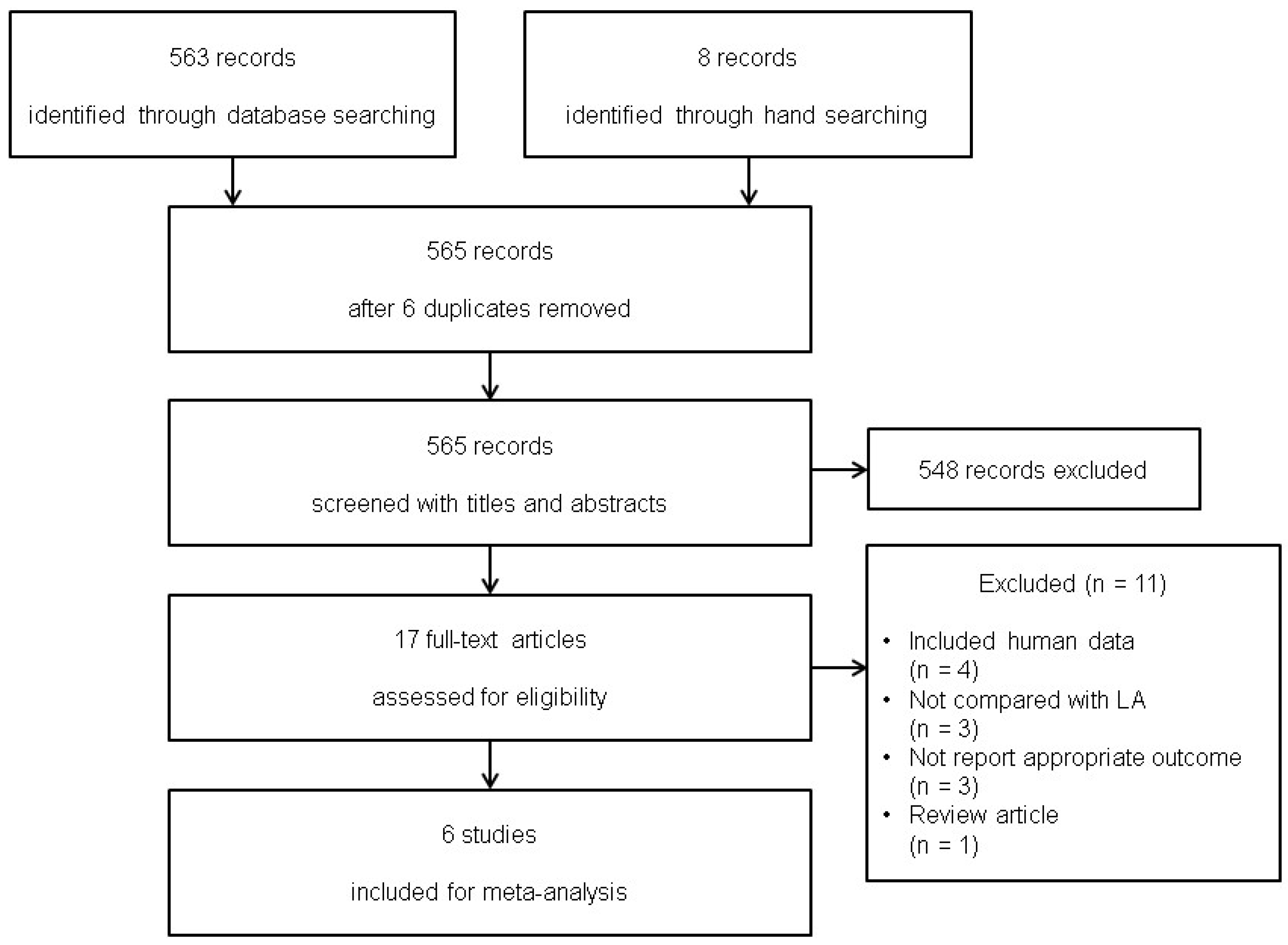

3.1. Study Selection

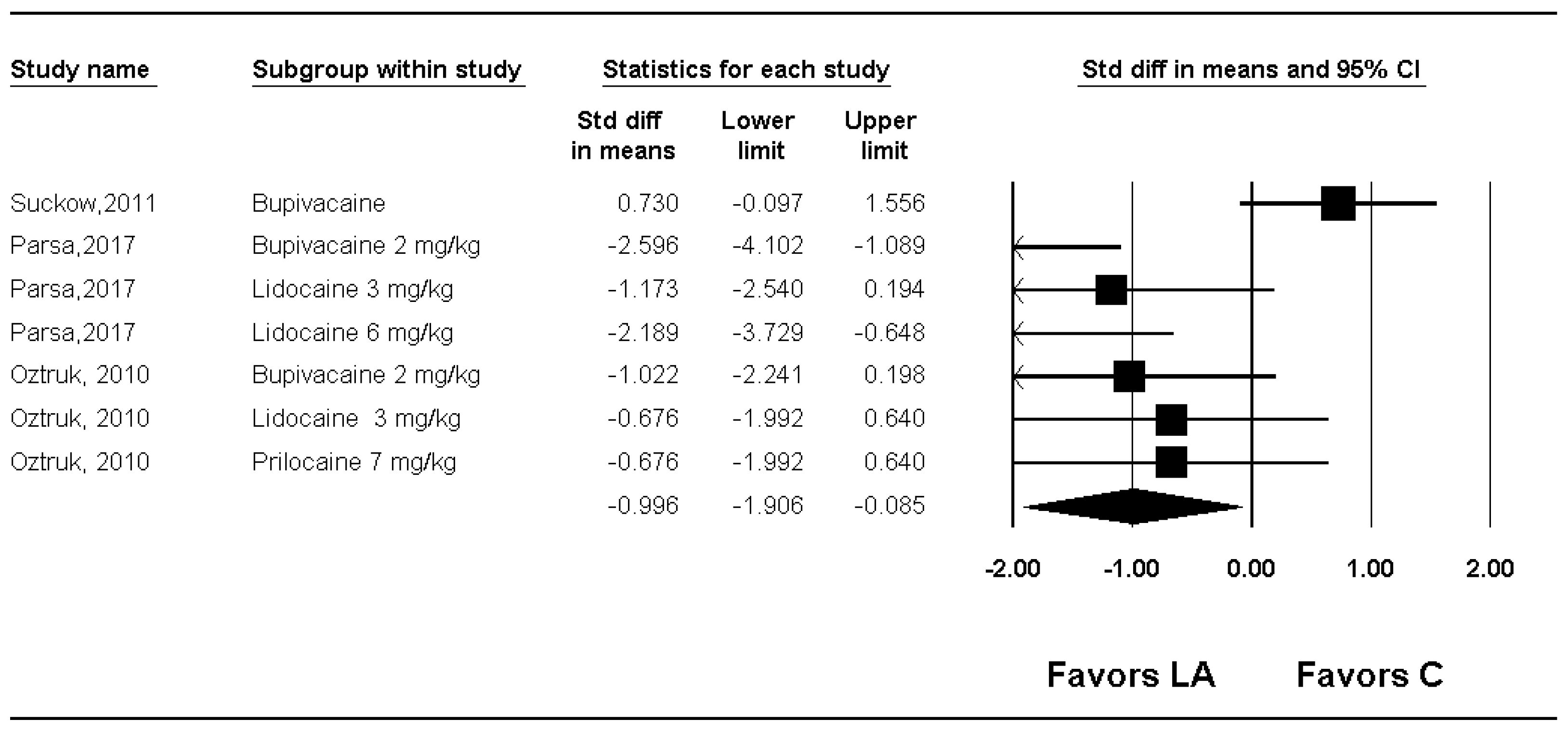

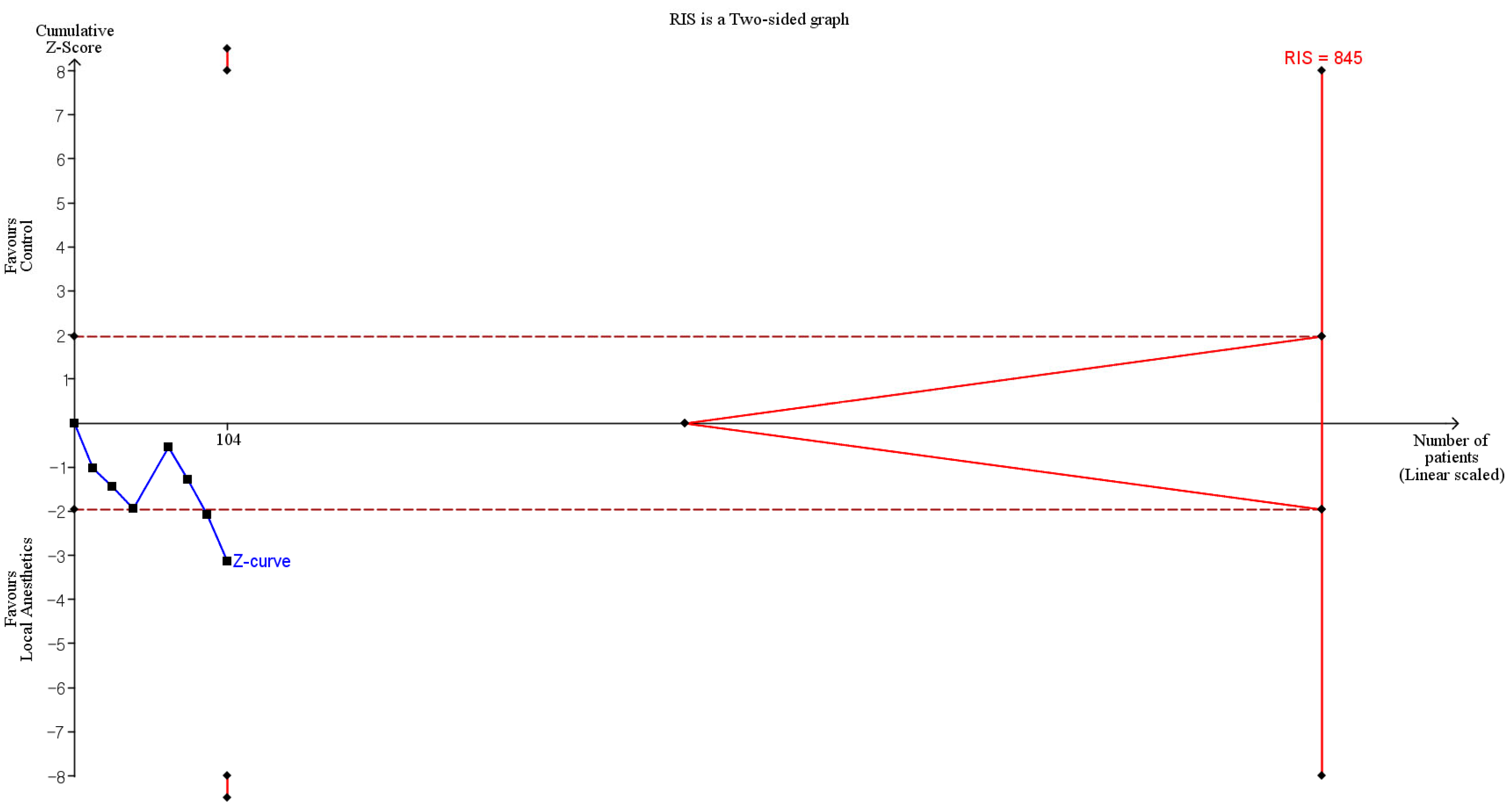

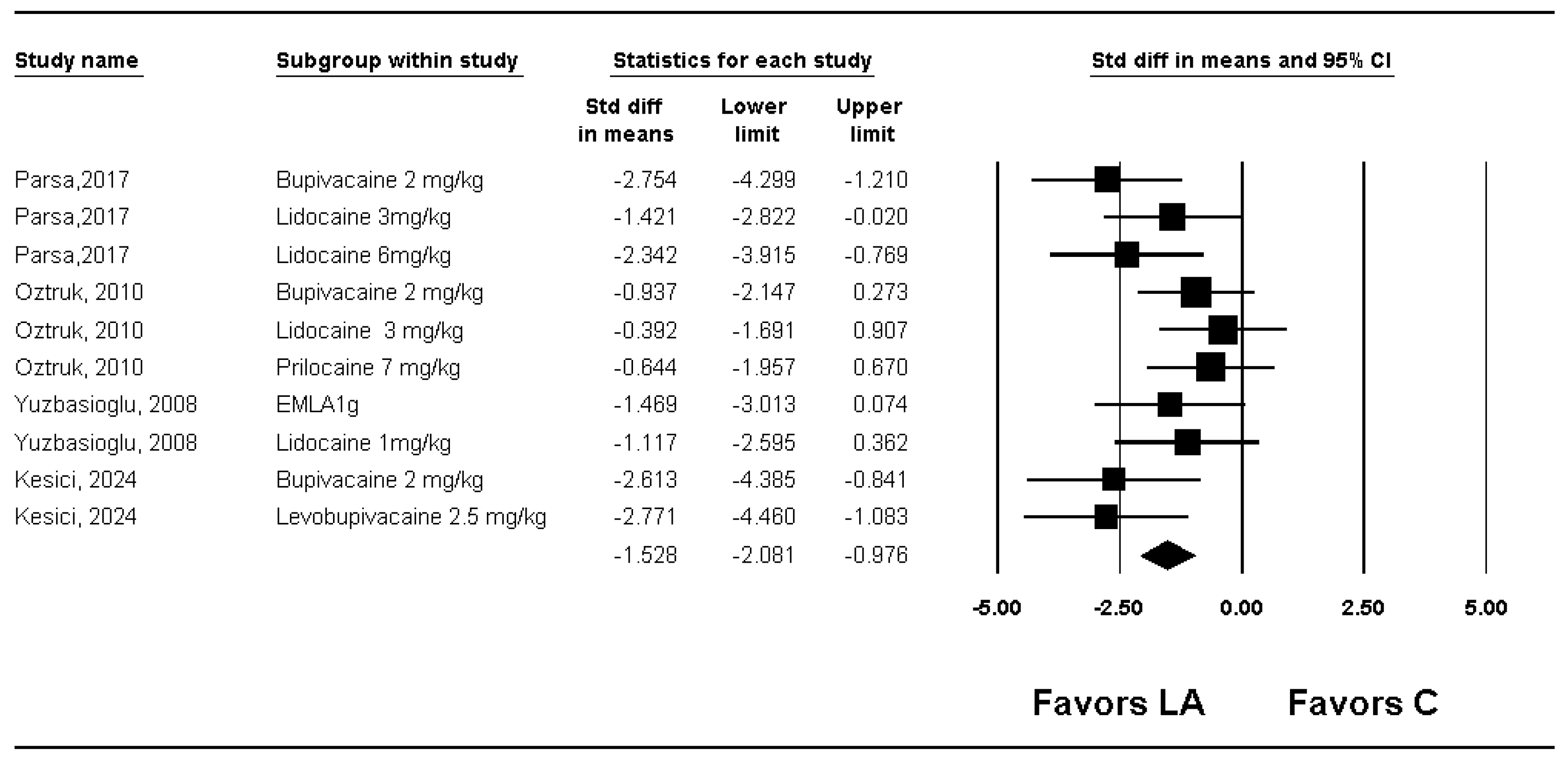

3.2. Macroscopic Adhesion Score

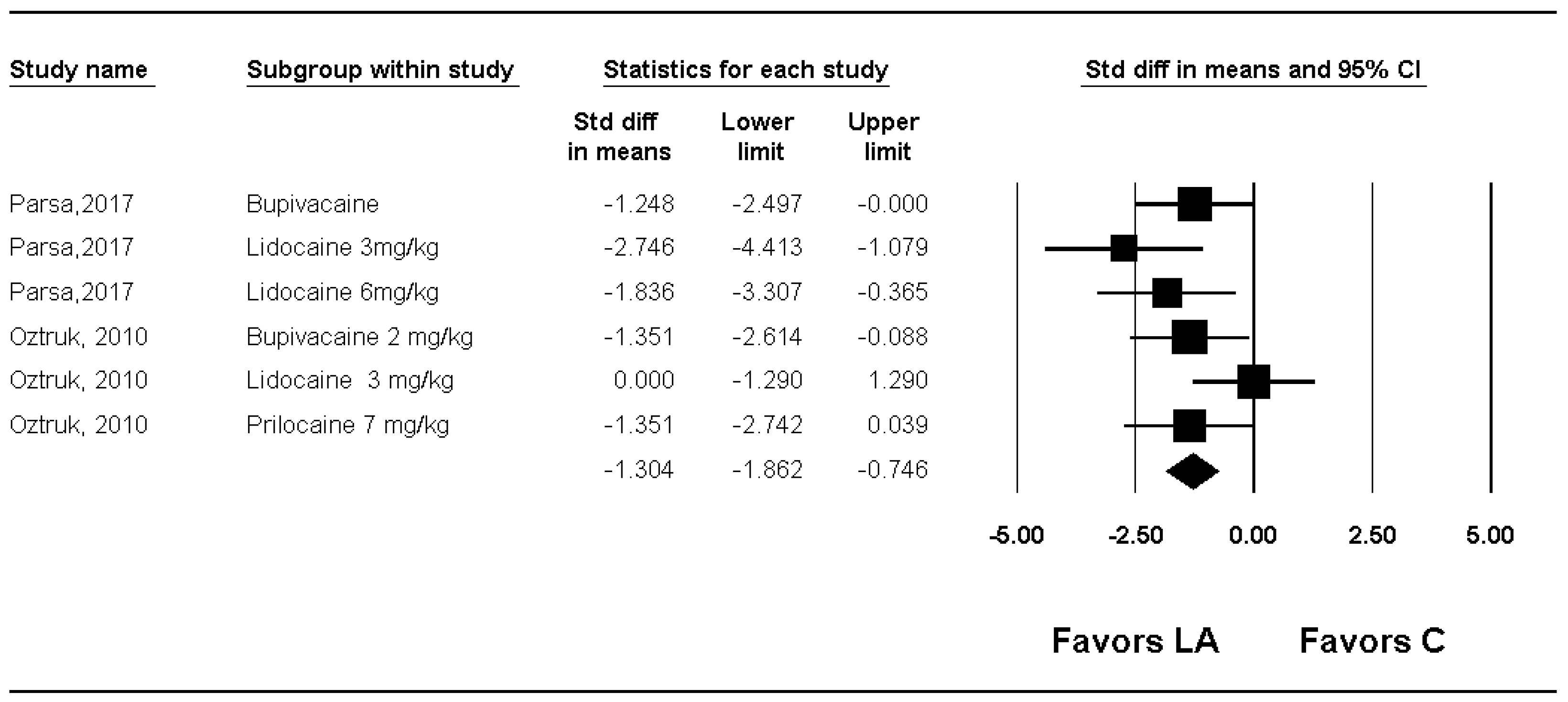

3.3. Microscopic Adhesion Score

3.4. Side Effect

3.5. Methodological Quality

3.6. Certainty of Evidence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| No | number |

| LA | local anesthetic |

| SMD | standardized mean difference |

| MD | mean difference |

| CI | confidence interval |

| TSA | trial sequential analysis |

| RIS | required information size |

References

- Josyula, A.; Parikh, K.S.; Pitha, I.; Ensign, L.M. Engineering biomaterials to prevent post-operative infection and fibrosis. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2021, 11, 1675–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulandi, T.; Chen, M.F.; Al-Took, S.; Watkin, K. A study of nerve fibers and histopathology of postsurgical, postinfectious, and endometriosis-related adhesions. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 92, 766–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouaïssi, M.; Gaujoux, S.; Veyrie, N.; Denève, E.; Brigand, C.; Castel, B.; Duron, J.J.; Rault, A.; Slim, K.; Nocca, D. Post-operative adhesions after digestive surgery: Their incidence and prevention: Review of the literature. J. Visc. Surg. 2012, 149, E104–E114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, H.; Moran, B.J.; Thompson, J.N.; Parker, M.C.; Wilson, M.S.; Menzies, D.; McGuire, A.; Lower, A.M.; Hawthorn, R.J.S.; O’Brien, F.; et al. Adhesion-related hospital readmissions after abdominal and pelvic surgery: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 1999, 353, 1476–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzies, D.; Ellis, H. Intestinal-obstruction from adhesions—How big is the problem. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 1990, 72, 60–63. [Google Scholar]

- Fortin, C.N.; Saed, G.M.; Diamond, M.P. Predisposing factors to post-operative adhesion development. Hum. Reprod. Update 2015, 21, 536–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollmann, M.W.; Durieux, M.E. Local anesthetics and the inflammatory response—A new therapeutic indication? Anesthesiol 2000, 93, 858–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, T.; Modig, J. Potential anti-thrombotic effects of local-anesthetics due to their inhibition of platelet-aggregation. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 1985, 29, 739–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The prisma statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.J.; Park, H.K.; Kim, D.S.; Lee, D.; Kang, H. Effect of statins on experimental postoperative adhesion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.H.; Choi, G.J.; Lee, O.H.; Kang, H. Effect of methylene blue on experimental postoperative adhesion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesici, U.; Karatepe, Y.K.; Mazlum, A.F.; Bozali, K.; Genç, M.S.; Ercan, L.D.; Duman, M.G.; Sade, A.G.; Guler, E.M.; Kesici, S. Effect of pre-incisional and peritoneal local anesthetics administration on colon anastomosis and wound healing. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2024, 30, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suckow, M.A.; Wolter, W.R.; Fecteau, C.; LaBadie-Suckow, S.M.; Johnson, C. Bupivacaine-enhanced small intestinal submucosa biomaterial as a hernia repair device. J. Biomater. Appl. 2012, 27, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuzbasioglu, M.F.; Ezberci, F.; Senoglu, N.; Ciragil, P.; Tolun, F.I.; Oksuz, H.; Cetinkaya, A.; Atli, Y.; Kale, I.T. Intraperitoneal emla (lidocaine/prilocaine) to prevent abdominal adhesion formation in a rat peritonitis model. Bratisl. Med. J.-Bratisl. Lek. Listy 2008, 109, 537–543. [Google Scholar]

- Parsa, H.; Saravani, H.; Sameei-Rad, F.; Nasiri, M.; Farahaninik, Z.; Rahmani, A. Comparing lavage of the peritoneal cavity with lidocaine, bupivacaine and normal saline to reduce the formation of abdominal adhesion bands in rats. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 24, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, E.; Yilmazlar, A.; Berhuni, S.; Yilmazlar, T. The effectiveness of local anesthetics in preventing postoperative adhesions in rat models. Tech. Coloproctology 2010, 14, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.J.; Kang, H.; Hong, M.E.; Shin, H.Y.; Baek, C.W.; Jung, Y.H.; Lee, Y.; Kim, J.W.; Park, I.K.; Cho, W.J. Effects of a lidocaine-loaded poloxamer/alginate/CaCl2 mixture on postoperative pain and adhesion in a rat model of incisional pain. Anesth. Analg. 2017, 125, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; de Vries, R.B.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. Syrcle’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IntHout, J.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Borm, G.F. The hartung-knapp-sidik-jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard dersimonian-laird method. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel-Levy, J.M. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of local anesthetics. In Topics in Local Anesthetics; Whizar-Lugo, V.M., Hernández-Cortez, E., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ozonur, V.A.; Salviz, E.A.; Sivrikoz, N.; Kozanoglu, E.; Karaali, S.; Gokduman, H.C.; Polat, H.; Emekli, U.; Tugrul, M.K.; Orhan-Sungur, M. Single and double injection paravertebral block comparison in reduction mammaplasty cases: A randomized controlled study. Anesth. Pain Med. 2023, 18, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hozo, S.P.; Djulbegovic, B.; Hozo, I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2005, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulinskaya, E.; Wood, J. Trial sequential methods for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 2014, 5, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooijmans, C.R.; de Vries, R.B.M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Rovers, M.M.; Leeflang, M.M.; IntHout, J.; Wever, K.E.; Hooft, L.; de Beer, H.; Kuijpers, T.; et al. Facilitating healthcare decisions by assessing the certainty in the evidence from preclinical animal studies. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0187271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchi, L.C.; Franciss, M.Y.; Zilberstein, B. Subcutaneous videosurgery for abdominal wall defects: A prospective observational study. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. 2019, 29, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecoffey, C.; Dubousset, A.M.; Trinquet, F.; Le Gal, M. Emla cream for venepuncture during induction of intravenous anaesthesia in children. Ann. Françaises D anesthésie Et Réanimation 1992, 11, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhibo, X.; Miaobo, Z. Effect of sustained-release lidocaine on reduction of pain after subpectoral breast augmentation. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2009, 29, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Campbell, R.E.; Leider, M.L.; Pepe, M.M.; Tucker, B.S.; Tjoumakaris, F.P. Efficacy of transdermal 4% lidocaine patches for postoperative pain management after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: A prospective trial. JSES Int. 2022, 6, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskildsen, M.P.R.; Kalliokoski, O.; Boennelycke, M.; Lundquist, R.; Settnes, A.; Lokkegaard, E. Autologous blood-derived patches used as anti-adhesives in a rat uterine horn damage model. J. Surg. Res. 2022, 275, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avsar, F.M.; Sahin, M.; Aksoy, F.; Avsar, A.F.; Aköz, M.; Hengirmen, S.; Bilici, S. Effects of diphenhydramine hcl and methylprednisolone in the prevention of abdominal adhesions. Am. J. Surg. 2001, 181, 512–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, B.; Koçkaya, E.A.; Atalay, C.; Akay, M.T. Polidocanol at different concentrations for pleurodesis in rats. Surg. Today 2005, 35, 1066–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C.W.; Lee, D.; Wu, M.H.; Chen, J.K.; He, H.L.; Liu, S.J. Lidocaine/ketorolac-loaded biodegradable nanofibrous anti-adhesive membranes that offer sustained pain relief for surgical wounds. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 5893–5901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, W.; Harmon, D.; Wang, J.H.; Ghori, K.; Shorten, G.; Redmond, P. The effect of lidocaine on in vitro neutrophil and endothelial adhesion molecule expression induced by plasma obtained during tourniquet-induced ischaemia and reperfusion. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2004, 21, 892–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, K.; Sakonju, I.; Kumakura, A.; Tomizawa, Z.; Kakuta, T.; Shimamura, S.; Okano, S.; Takase, K. Effects of lidocaine hydrochloride on canine granulocytes, granulocyte cd11b expression and reactive oxygen species production. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2010, 72, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mitra, S.; Khandelwal, P.; Roberts, K.; Kumar, S.; Vadivelu, N. Pain relief in laparoscopic cholecystectomy-a review of the current options. Pain Pract. 2012, 12, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bothin, C.; Okada, M.; Midtvedt, T.; Perbeck, L. The intestinal flora influences adhesion formation around surgical anastomoses. Br. J. Surg. 2001, 88, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roohbakhsh, Y.; Rahimi, V.B.; Silakhori, S.; Rajabi, H.; Rahmanian-Devin, P.; Samzadeh-Kermani, A.; Rakhshandeh, H.; Hasanpour, M.; Iranshahi, M.; Mousavi, S.H.; et al. Evaluation of the effects of peritoneal lavage with rosmarinus officinalis extract against the prevention of postsurgical-induced peritoneal adhesion. Planta Med. 2020, 86, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejedor, A.; Deiros, C.; Bijelic, L.; García, M. Wound infiltration or transversus abdominis plane block after laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: A randomized clinical trial. Anesth. Pain Med. 2023, 18, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ökmen, K.; Yıldız, D.K. Effect of interfascial pressure on block success during anterior quadratus lumborum block application: A prospective observational study. Anesth. Pain Med. 2023, 18, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Lee, H. Challenging issues of implementing enhanced recovery after surgery programs in South Kore. Anesth. Pain Med. 2024, 19, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamill, J.K.; Rahiri, J.L.; Hill, A.G. Analgesic effect of intraperitoneal local anesthetic in surgery: An overview of systematic reviews. J. Surg. Res. 2017, 15, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author, Publication Year | Animal | Surgery | Group | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yuzbasioglu, 2008 [15] | Wistar rats | Laparotomy | Control | No irrigation |

| Group 1 | Lidocaine 2.5%, prilocaine 2.5% | |||

| Group 2 | Lidocaine 2.5% (1 mg/kg) | |||

| Group 3 | Ceftriaxone (100 mg/kg) | |||

| Ozturk, 2010 [17] | Wistar-Albino rats | Laparotomy | Control | No irrigation |

| Group 1 | Saline (5 mL) | |||

| Group 2 | Lidocaine (7 mg/kg) | |||

| Group 3 | Lidocaine (3 mg/kg) | |||

| Group 4 | Bupivacaine (2 mg/kg) | |||

| Suckow, 2012 [14] | Sprague Dawley rats | Laparotomy | Group 1 | No irrigation |

| Group 2 | Bupivacaine | |||

| Parsa, 2017 [16] | Sprague Dawley rats | Laparotomy | Control | No irrigation |

| Group 2 | Normal saline (0.9% sodium chloride solution) | |||

| Group 3 | Lidocaine 2% (3 mg/kg) | |||

| Group 4 | Lidocaine 2% (6 mg/kg) | |||

| Group 5 | Bupivacaine | |||

| Choi, 2017 [18] | Sprague Dawley rats | Incisional pain model | Group S | No irrigation |

| Group P | PACM | |||

| Group PL0.5 | 0.5% lidocaine-loaded PACM | |||

| Group PL1 | 1% lidocaine-loaded PACM | |||

| Group PL2 | 2% lidocaine-loaded PACM | |||

| Group PL4 | 4% lidocaine-loaded PACM | |||

| Kesici, 2024 [13] | Sprague Dawley rats | Laparotomy + colon anastomosis | Group C | Isotonic solution |

| Group B | Pre-incisional bupivacaine 2 mg/kg + peritoneal bupivacaine 2 mg/kg | |||

| Group L | Pre-incisional levobupivacaine 2.5 mg/kg + peritoneal levobupivacaine 2.5 mg/kg |

| Outcome | No. of Studies | No. of Animals | Conventional Meta-Analysis | Trial Sequential Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMD with 95% CI | Heterogeneity (I2) | Conventional Test Boundary | Monitoring Boundary | RIS | ||||

| Macroscopic adhesion score | Quality (or tenacity of adhesion) | 3 | 104 | Significant (SMD: −0.996; 95% CI −1.906 to −0.085) | 72.6 | Cross | Not cross | 12.3% (104 of 845 animals) |

| Quantity (or extent of adhesion) | 3 | 104 | Not significant (SMD −0.544; 95% CI −1.452 to 0.365) | 77.6 | Not cross | Not cross | 13.5% (104 of 770 animals) | |

| Total adhesion score | 4 | 98 | Significant (SMD −1.528; 95% CI −2.081 to −0.976) | 30.0 | Cross | Not cross | 4.1% (119 of 2936 animals) | |

| Microscopic adhesion score | Severity | 2 | 80 | Significant (SMD −1.304; 95% CI −1.862 to −0.746) | 31.7 | |||

| Inflammation | 1 | 84 | Not significant (SMD: −1.833; 95% CI −4.017 to 0.350) | 90.9 | ||||

| Fibrosis | 1 | 84 | Significant (SMD: −2.373; 95% CI −3.400 to −1.346) | 60.4 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.-h.; Lee, D.; Kang, H. Effect of Local Anesthetics on Experimental Postoperative Adhesion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Trial Sequential Analysis. Medicina 2025, 61, 2215. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122215

Lee J-h, Lee D, Kang H. Effect of Local Anesthetics on Experimental Postoperative Adhesion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Trial Sequential Analysis. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2215. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122215

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Joon-hee, Donghyun Lee, and Hyun Kang. 2025. "Effect of Local Anesthetics on Experimental Postoperative Adhesion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Trial Sequential Analysis" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2215. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122215

APA StyleLee, J.-h., Lee, D., & Kang, H. (2025). Effect of Local Anesthetics on Experimental Postoperative Adhesion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Trial Sequential Analysis. Medicina, 61(12), 2215. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122215