Multi-Omics and Functional Analysis of BFSP1 as a Prognostic and Therapeutic Target in Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

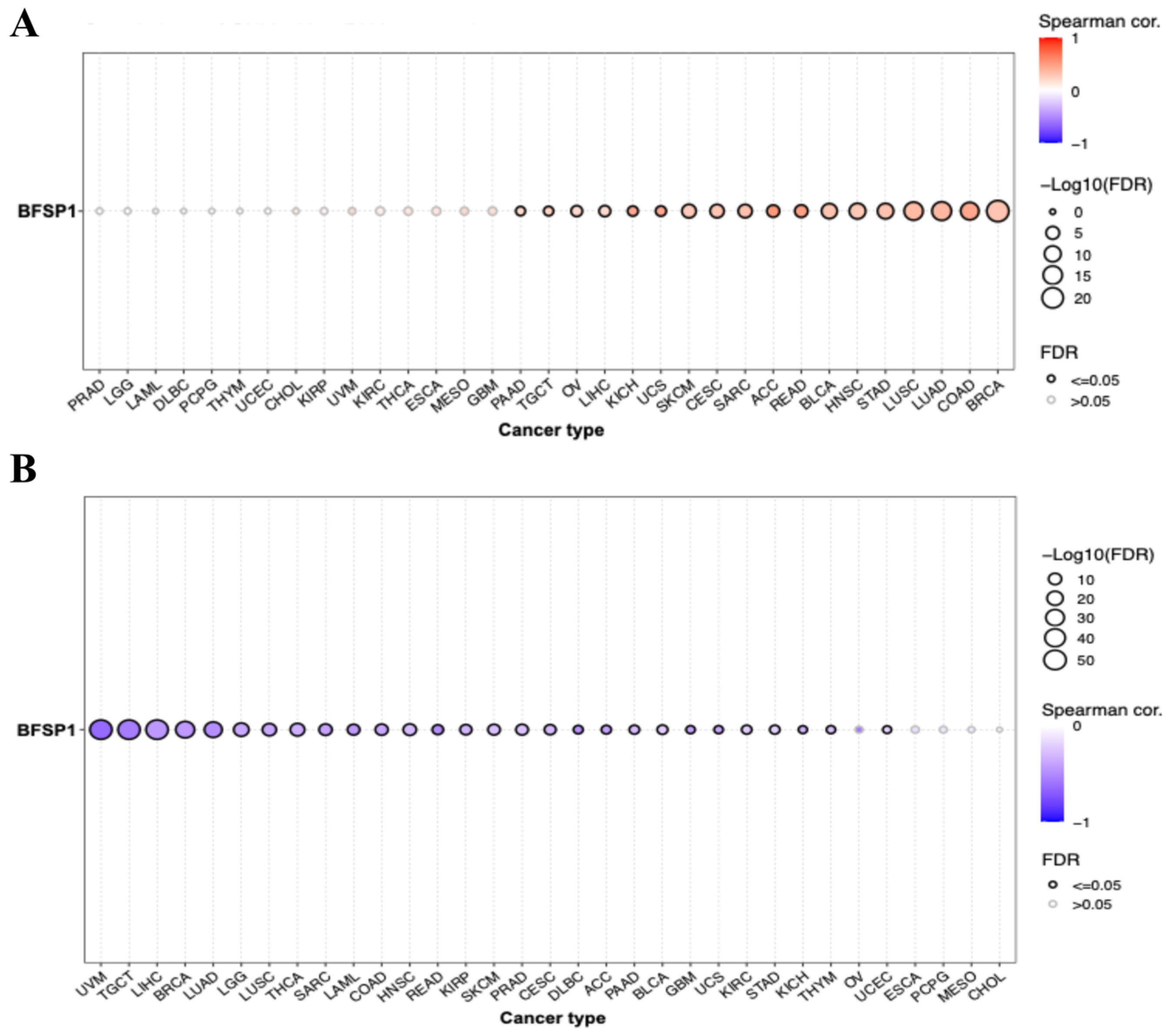

2.1. mRNA Expression Analysis of BFSP1 in LIHC

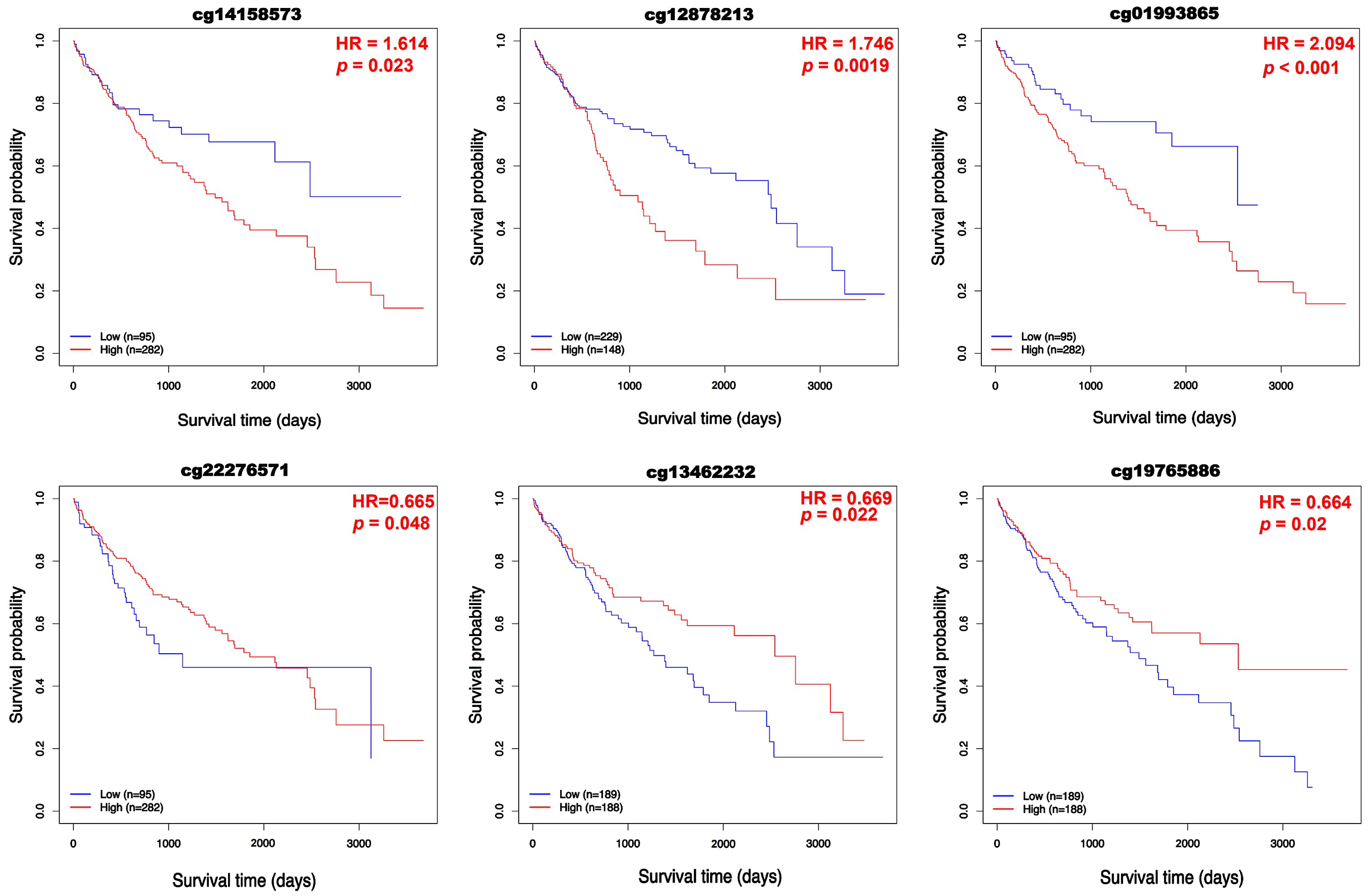

2.2. Prognostic Analysis of BFSP1 in LIHC

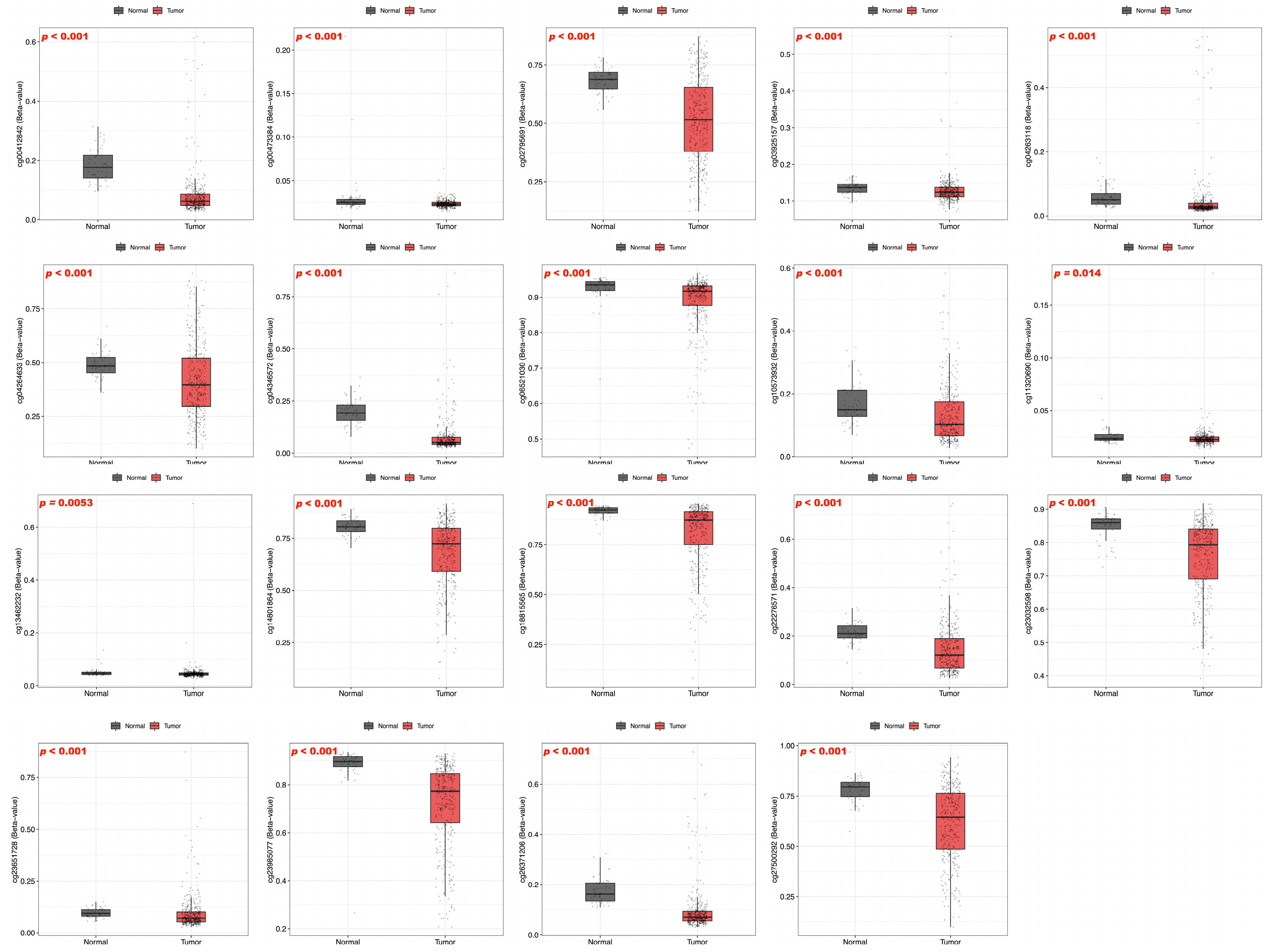

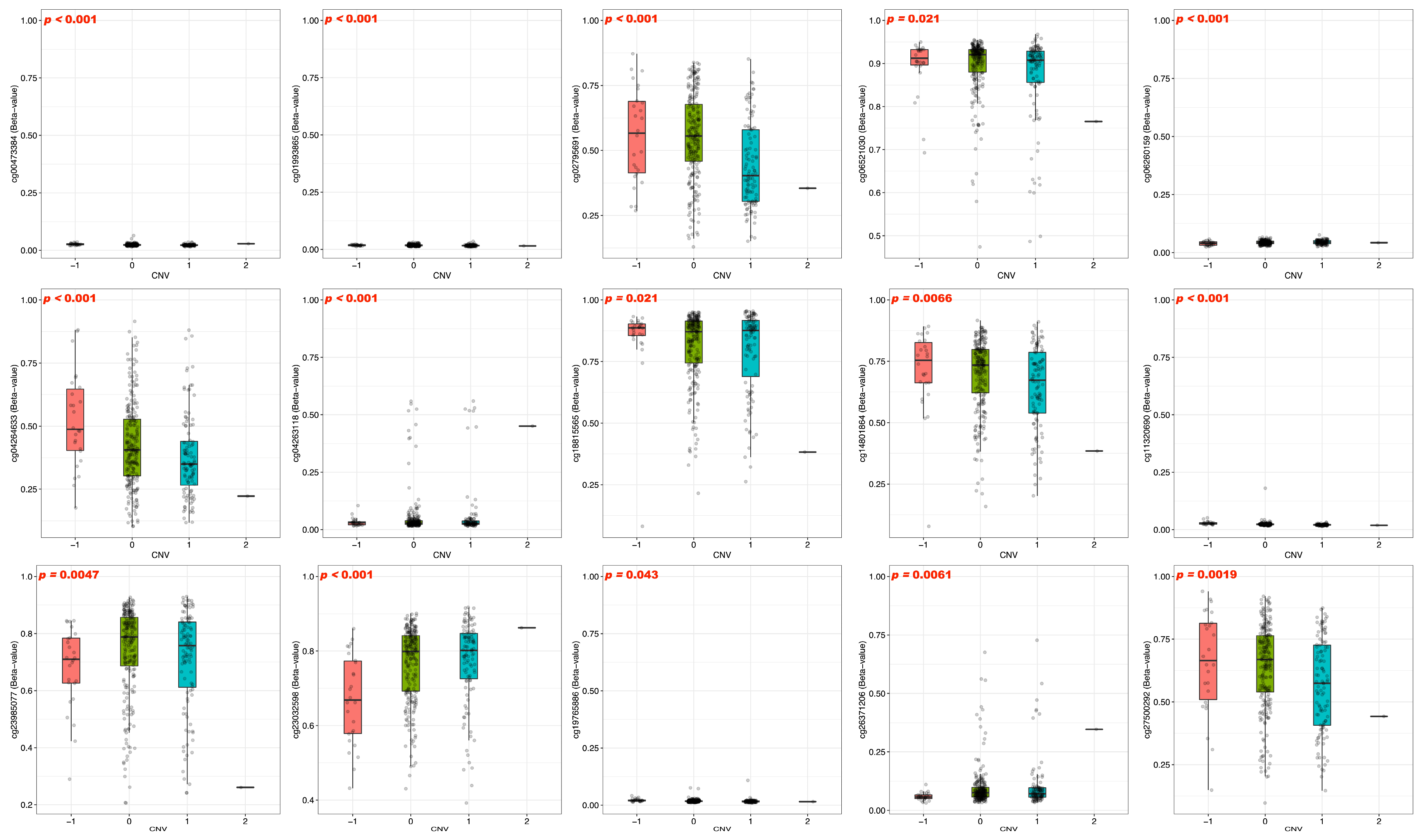

2.3. DNA Methylation and Prognostic Analysis of BFSP1 in LIHC

2.4. Immune Infiltration and Drug Sensitivity Analysis of BFSP1 in LIHC

2.5. Gene–Chemical Interaction Analysis of BFSP1

2.6. Co-Expression Network and Functional Enrichment Analysis of BFSP1

2.7. Prognostic Analysis of Co-Expressed Genes Associated with BFSP1 in LIHC

2.8. Gene–Gene Interaction Network Analysis of BFSP1 in LIHC

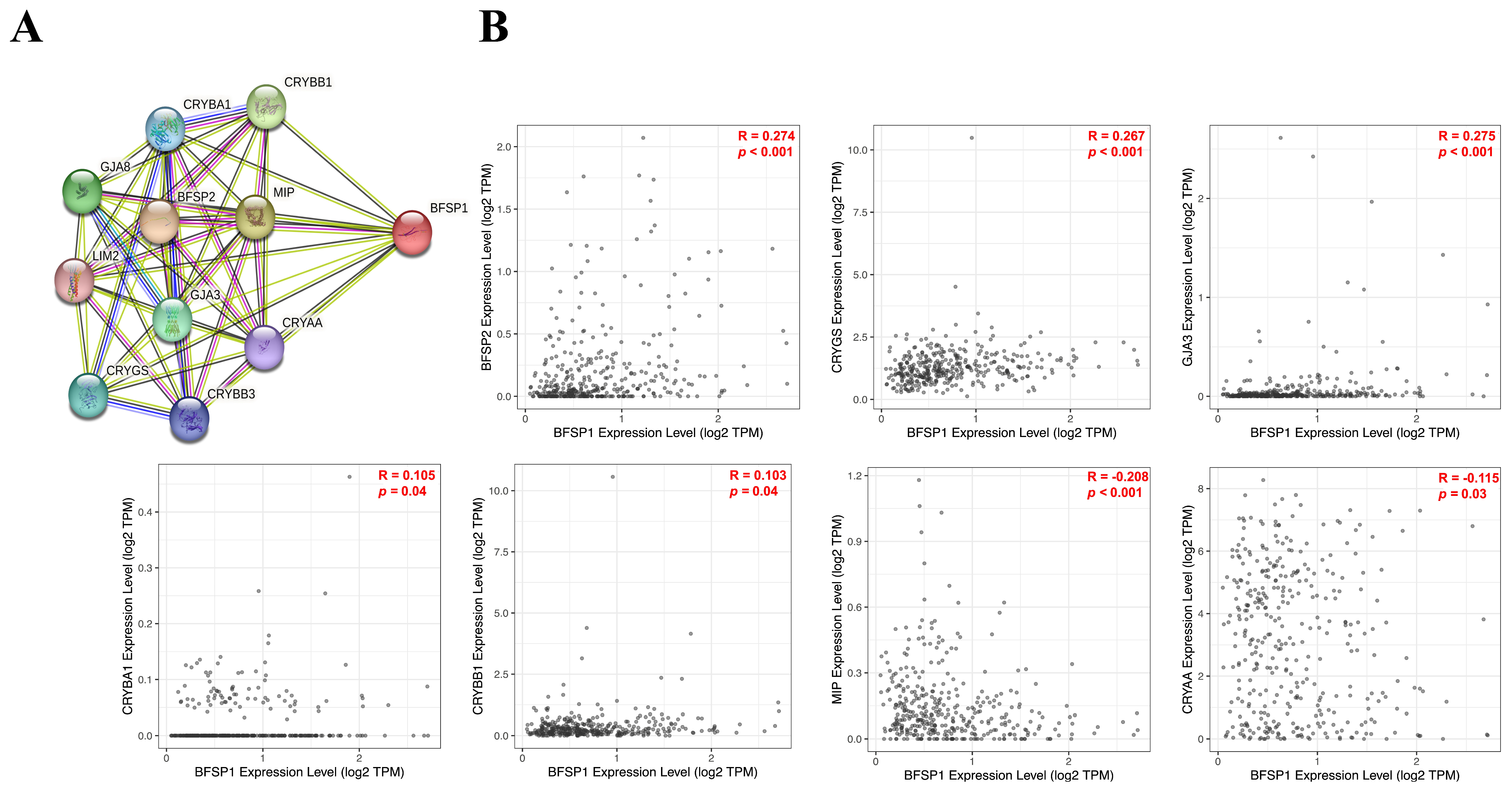

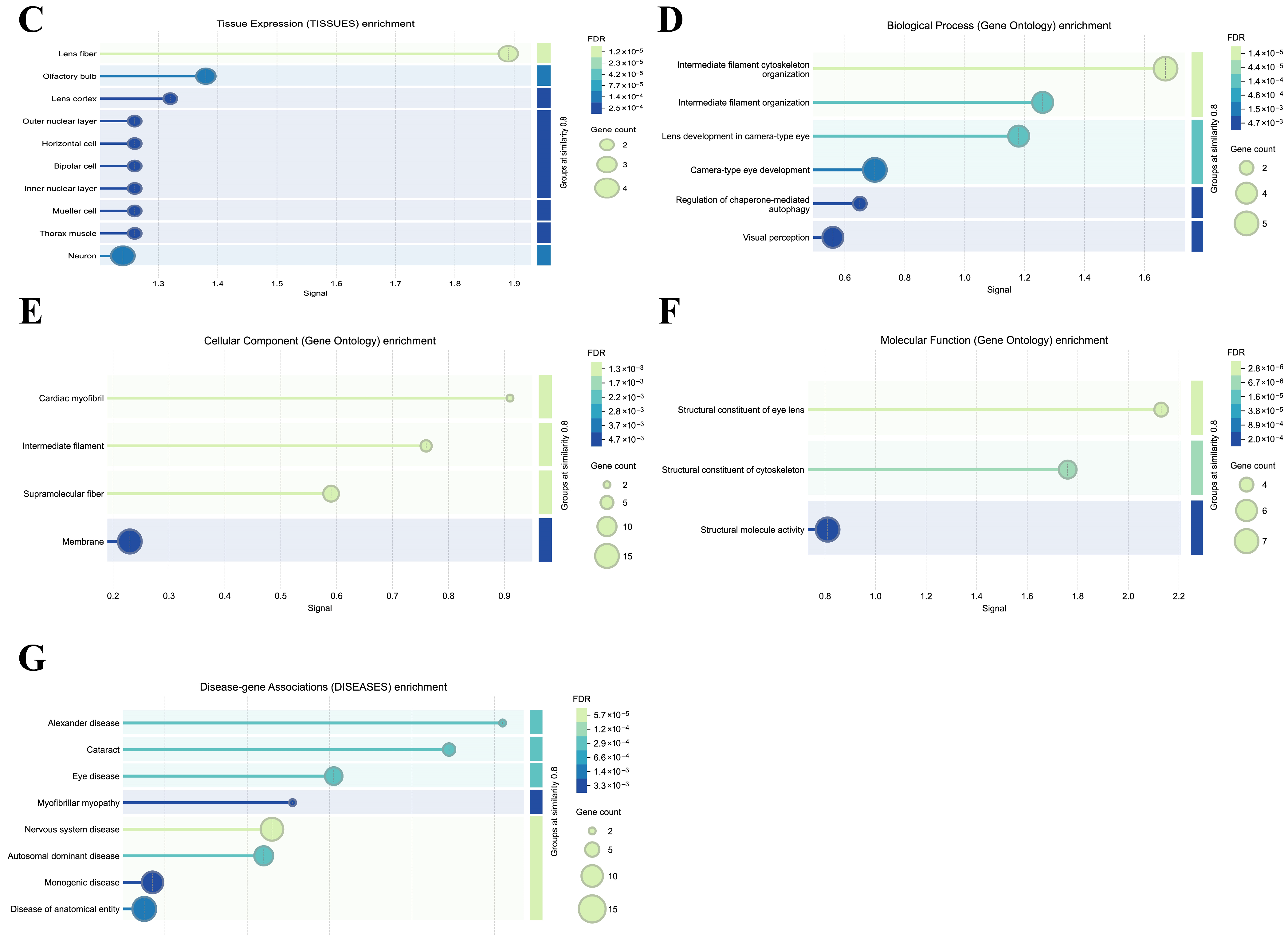

2.9. Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) Network and Enrichment of BFSP1

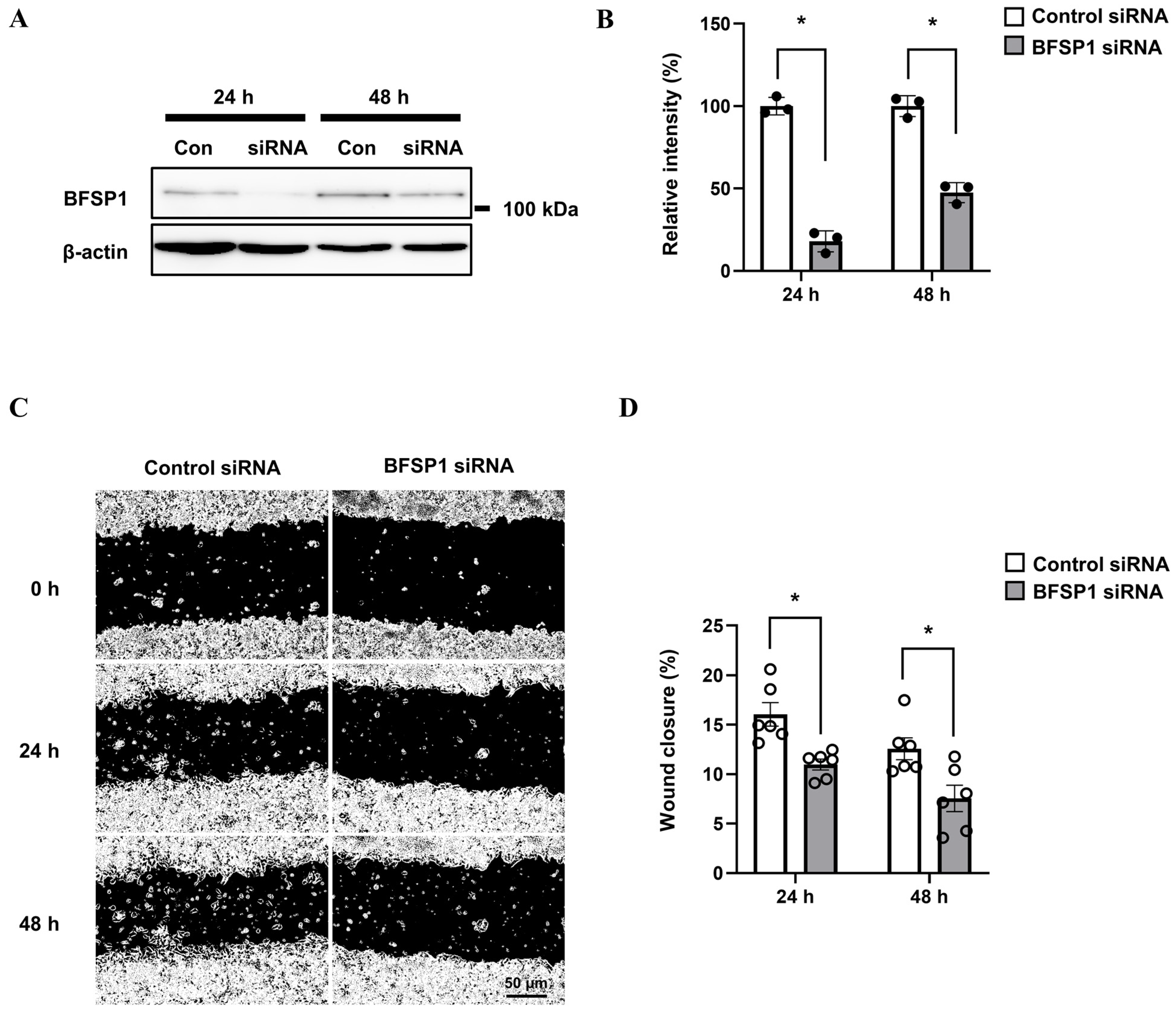

2.10. siRNA Transfection Analysis

2.11. Western Blotting Analysis

2.12. Wound Healing Assay

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. mRNA Expression of BFSP1 in LIHC

3.2. Prognostic Value of BFSP1 Expression in LIHC

3.3. DNA Methylation and Prognosis of BFSP1 in LIHC

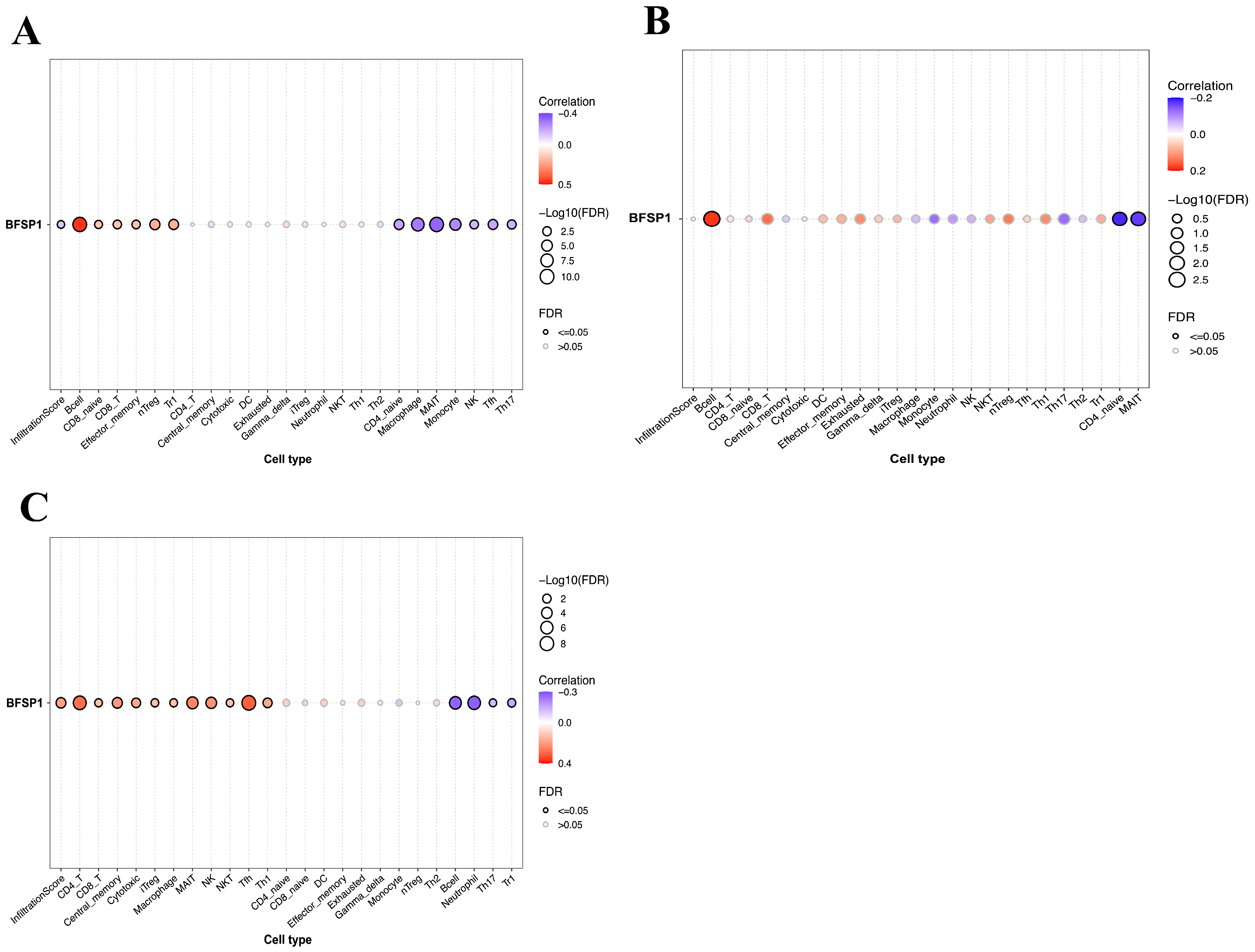

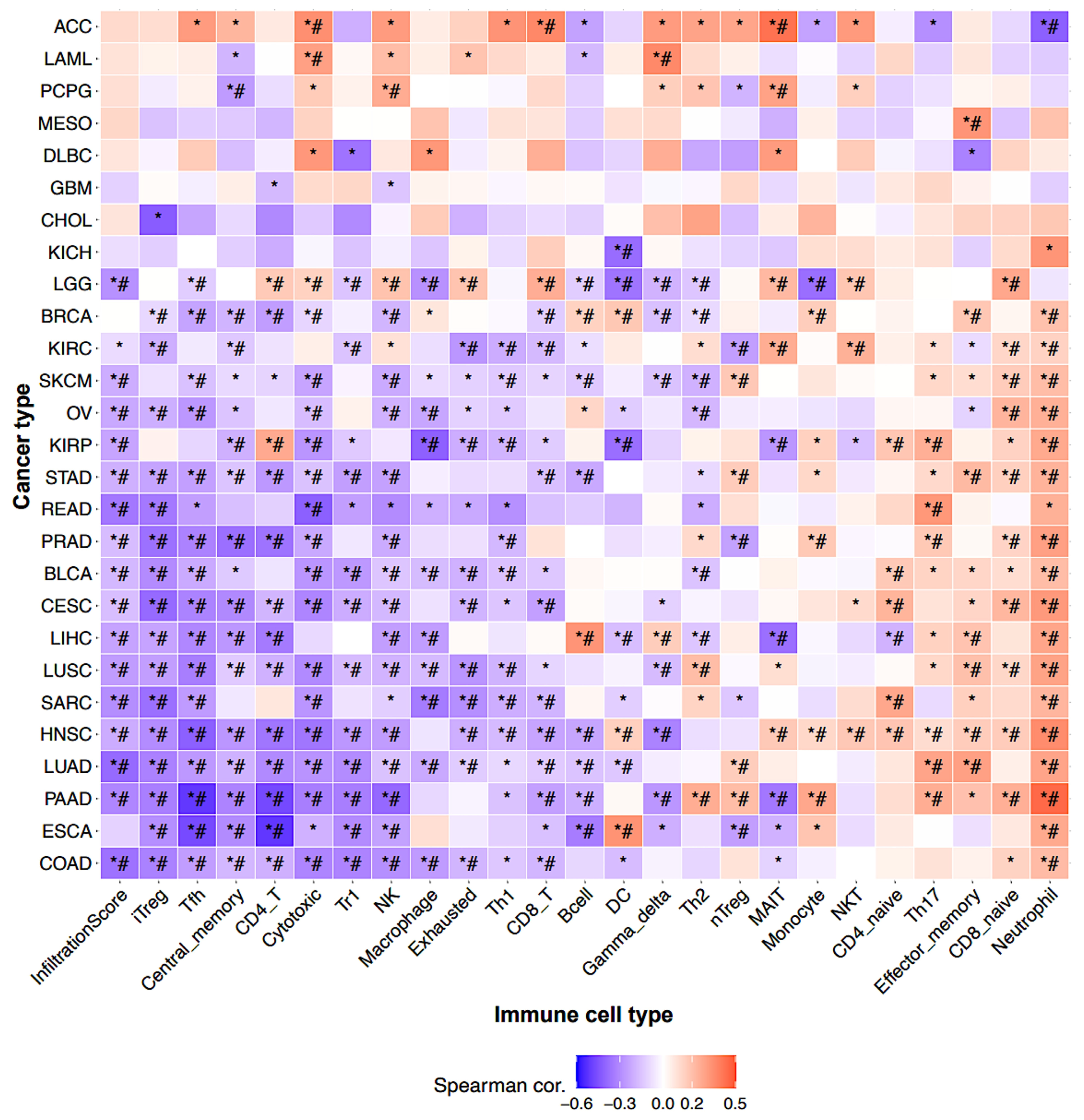

3.4. Correlation Between BFSP1 and Immune Cell Infiltration in LIHC

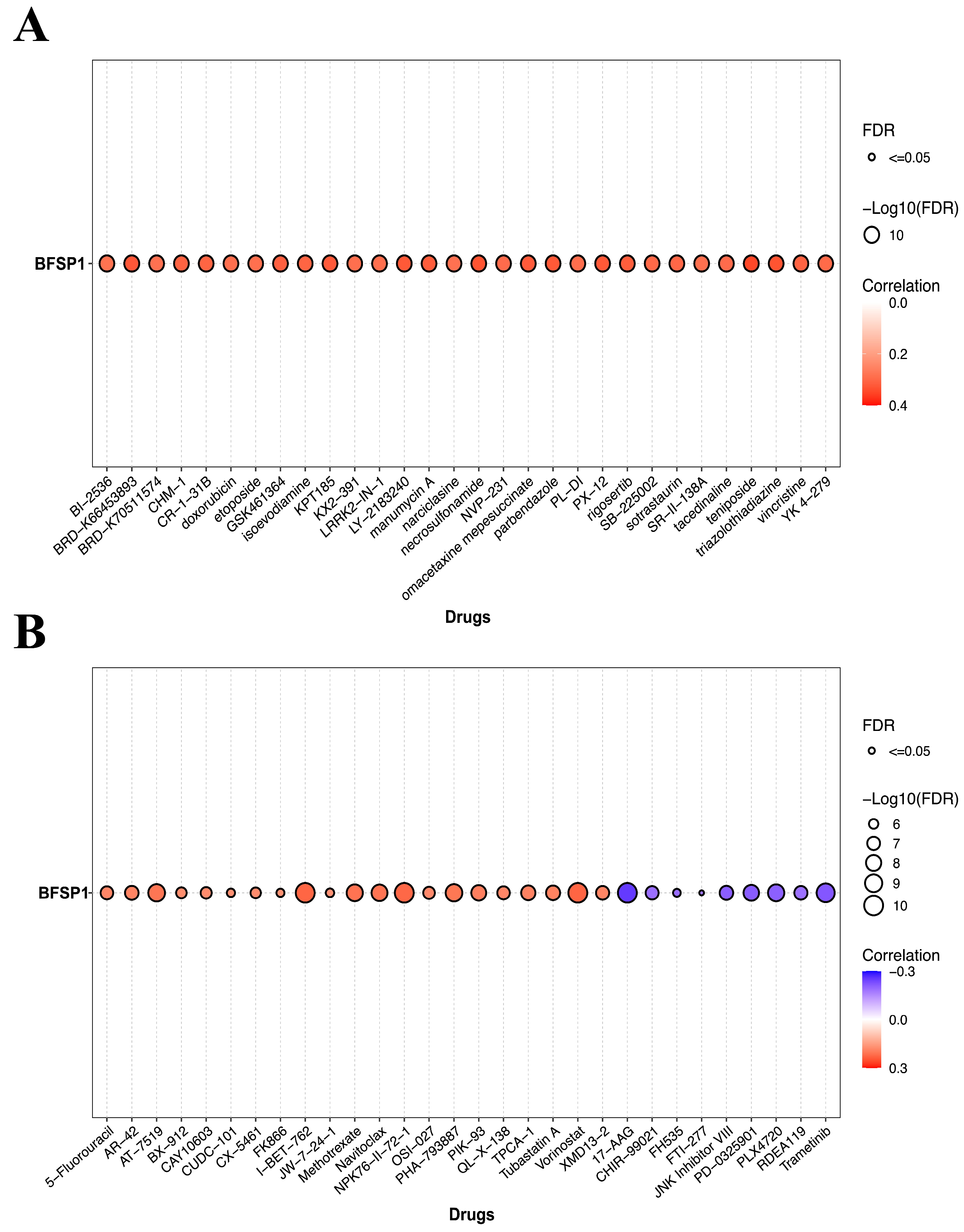

3.5. Association Between BFSP1 Expression and Drug Sensitivity in LIHC

3.6. Interactions Between BFSP1 Expression and Chemicals in LIHC

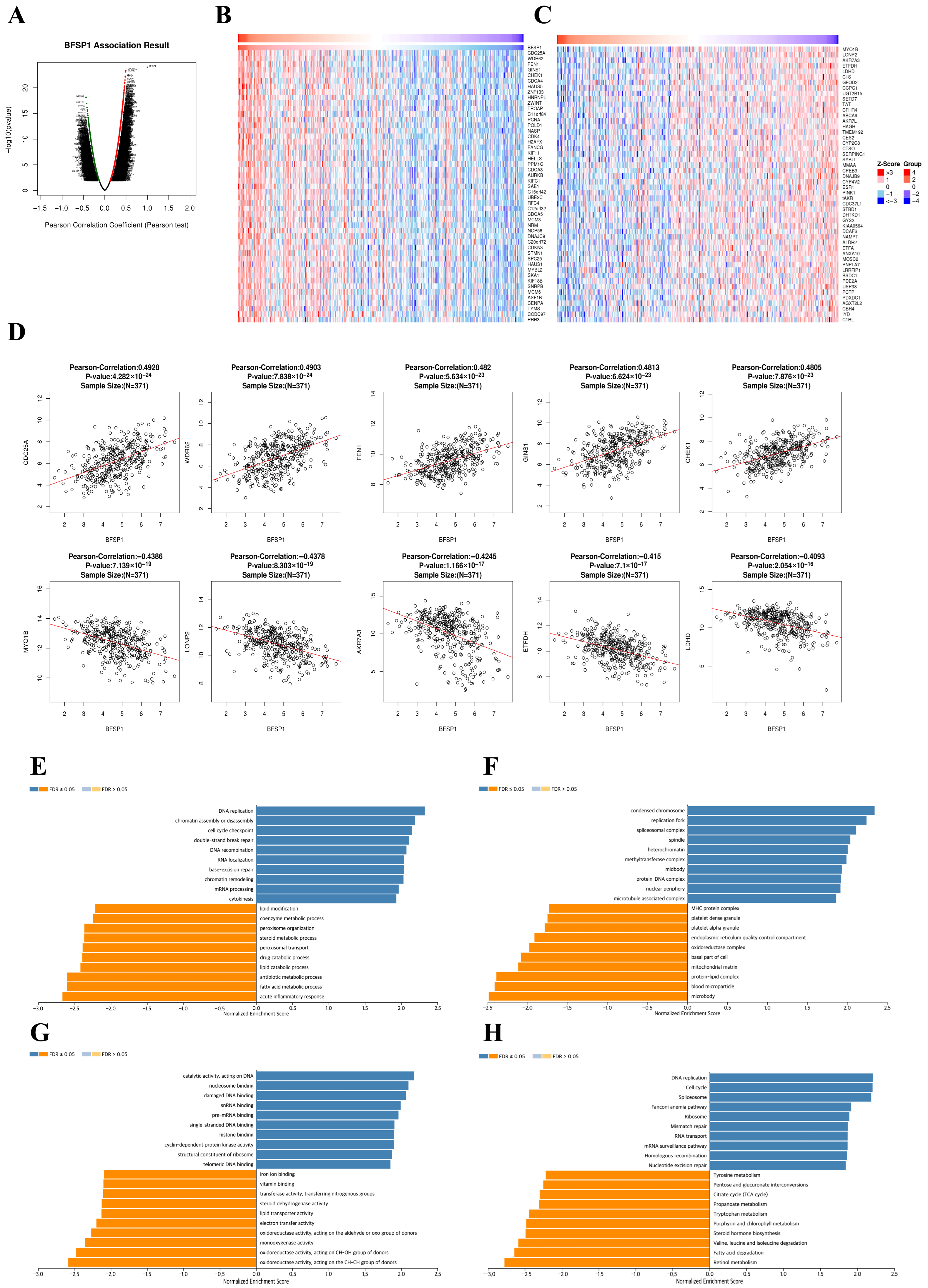

3.7. Co-Expression and Functional Enrichment Analysis of BFSP1 in LIHC

3.8. Prognostic Value of BFSP1-Associated Genes in LIHC

3.9. Gene–Gene Interaction Network Analysis of BFSP1

3.10. Protein–Protein Interaction and Functional Enrichment Analysis of BFSP1 in LIHC

3.11. Protein Expression and Cell Migration in HepG2 Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BFSP1 | beaded filament structural protein 1 |

| CNV | copy number variation |

| CTD | Comparative Toxicogenomics Database |

| DSS | disease-specific survival |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| GSCA | Gene Set Context Analysis |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| LIHC | liver hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HR | hazard ratio |

| MAIT | mucosal-associated invariant T |

| NK | natural killer |

| OS | overall survival |

| PPI | protein–protein interaction |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| Treg | regulatory T cell |

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Kim, J. CBX1 as a Prognostic Biomarker and Therapeutic Target in Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Insight into DNA Methylation and Non-Coding RNA Networks from Comprehensive Bioinformatics Analysis. Medicina 2025, 61, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, C.; Dong, X.; Li, H.; Cao, M.; Sun, D.; He, S.; Yang, F.; Yan, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, N.; et al. Cancer statistics in China and United States, 2022: Profiles, trends, and determinants. Chin. Med. J. 2022, 135, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannou, G.N.; Splan, M.F.; Weiss, N.S.; McDonald, G.B.; Beretta, L.; Lee, S.P. Incidence and predictors of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 5, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Dikshit, R.; Eser, S.; Mathers, C.; Rebelo, M.; Parkin, D.M.; Forman, D.; Bray, F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, E359–E386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemal, A.; Ward, E.M.; Johnson, C.J.; Cronin, K.A.; Ma, J.; Ryerson, B.; Mariotto, A.; Lake, A.J.; Wilson, R.; Sherman, R.L.; et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975–2014, Featuring Survival. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109, djx030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin 2020, 70, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colagrande, S.; Inghilesi, A.L.; Aburas, S.; Taliani, G.G.; Nardi, C.; Marra, F. Challenges of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 7645–7659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Li, S.M.; Atchison, D.A.; Kang, M.T.; Wei, S.; He, X.; Bai, W.; Li, H.; Kang, Y.; Cai, Z.; et al. Association Between Color Vision Deficiency and Myopia in Chinese Children Over a Five-Year Period. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2022, 63, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Liu, M.; Zhang, C. Construction of a prognostic model and identification of key genes in liver hepatocellular carcinoma based on multi-omics data. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Lu, Y.; Liu, R.; Huang, L.; Xu, K.; Xiong, H.; Nan, D.; Shou, Y.; Sheng, H.; Zhang, H.; et al. LZTS2 methylation as a potential diagnostic and prognostic marker in LIHC and STAD: Evidence from bioinformatics and in vitro analyses. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.H.; Yang, D.L.; Wang, L.; Liu, J. Epigenetic and Immune-Cell Infiltration Changes in the Tumor Microenvironment in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 793343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Lu, Q. Genetic and epigenetic influences on the loss of tolerance in autoimmunity. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2018, 15, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarrin, M.; Kalligeraki, A.A.; Uwineza, A.; Cawood, C.S.; Brown, A.P.; Ward, E.N.; Le, K.; Freitag-Pohl, S.; Pohl, E.; Kiss, B.; et al. Independent Membrane Binding Properties of the Caspase Generated Fragments of the Beaded Filament Structural Protein 1 (BFSP1) Involves an Amphipathic Helix. Cells 2023, 12, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapodi, A.; Clemens, D.M.; Uwineza, A.; Jarrin, M.; Goldberg, M.W.; Thinon, E.; Heal, W.P.; Tate, E.W.; Nemeth-Cahalan, K.; Vorontsova, I.; et al. BFSP1 C-terminal domains released by post-translational processing events can alter significantly the calcium regulation of AQP0 water permeability. Exp. Eye Res. 2019, 185, 107585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Landsbury, A.; Dahm, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Quinlan, R.A. Functions of the intermediate filament cytoskeleton in the eye lens. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 1837–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, S.; Shen, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, D.; Yu, J.; Huang, L.; Liu, N.; Lu, H.; Xu, M. M6A-modified BFSP1 induces aerobic glycolysis to promote liver cancer growth and metastasis through upregulating tropomodulin 4. Mol. Biomed. 2025, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veres, B.; Eros, K.; Antus, C.; Kalman, N.; Fonai, F.; Jakus, P.B.; Boros, E.; Hegedus, Z.; Nagy, I.; Tretter, L.; et al. Cyclophilin D-dependent mitochondrial permeability transition amplifies inflammatory reprogramming in endotoxemia. FEBS Open Bio 2021, 11, 684–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Guan, J.; Xu, J.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, C.; Yang, Q.; Huang, C.; Wang, G.; Zhou, H.; Chen, Z.; et al. Model based on five tumour immune microenvironment-related genes for predicting hepatocellular carcinoma immunotherapy outcomes. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Qi, D.; Zhu, B.; Ye, X. Analysis of m6A RNA Methylation-Related Genes in Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Their Correlation with Survival. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentles, A.J.; Newman, A.M.; Liu, C.L.; Bratman, S.V.; Feng, W.; Kim, D.; Nair, V.S.; Xu, Y.; Khuong, A.; Hoang, C.D.; et al. The prognostic landscape of genes and infiltrating immune cells across human cancers. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, N.; Kudo, M. Immunological Microenvironment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Its Clinical Implication. Oncology 2017, 92, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Shuen, T.W.H.; Toh, T.B.; Chan, X.Y.; Liu, M.; Tan, S.Y.; Fan, Y.; Yang, H.; Lyer, S.G.; Bonney, G.K.; et al. Development of a new patient-derived xenograft humanised mouse model to study human-specific tumour microenvironment and immunotherapy. Gut 2018, 67, 1845–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremnes, R.M.; Al-Shibli, K.; Donnem, T.; Sirera, R.; Al-Saad, S.; Andersen, S.; Stenvold, H.; Camps, C.; Busund, L.T. The role of tumor-infiltrating immune cells and chronic inflammation at the tumor site on cancer development, progression, and prognosis: Emphasis on non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2011, 6, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, R.; Lauss, M.; Sanna, A.; Donia, M.; Skaarup Larsen, M.; Mitra, S.; Johansson, I.; Phung, B.; Harbst, K.; Vallon-Christersson, J.; et al. Tertiary lymphoid structures improve immunotherapy and survival in melanoma. Nature 2020, 577, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnewies, M.; Roberts, E.W.; Kersten, K.; Chan, V.; Fearon, D.F.; Merad, M.; Coussens, L.M.; Gabrilovich, D.I.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S.; Hedrick, C.C.; et al. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sia, D.; Jiao, Y.; Martinez-Quetglas, I.; Kuchuk, O.; Villacorta-Martin, C.; Castro de Moura, M.; Putra, J.; Camprecios, G.; Bassaganyas, L.; Akers, N.; et al. Identification of an Immune-specific Class of Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Based on Molecular Features. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 812–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, F.S. Clinical immunology and immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: Current progress and challenges. Hepatol. Int. 2019, 13, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reig, M.; Forner, A.; Rimola, J.; Ferrer-Fabrega, J.; Burrel, M.; Garcia-Criado, A.; Kelley, R.K.; Galle, P.R.; Mazzaferro, V.; Salem, R.; et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Huang, H.; Li, M.; Liang, X.; Tan, Y.; Chen, Y. Lactylation-Related Gene Signature Effectively Predicts Prognosis and Treatment Responsiveness in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.H.; Kim, R.B.; Park, S.Y.; Park, J.; Jung, E.J.; Ju, Y.T.; Jeong, C.Y.; Park, M.; Ko, G.H.; Song, D.H.; et al. Nomogram for predicting gastric cancer recurrence using biomarker gene expression. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 46, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goncalves, E.; Goncalves-Reis, M.; Pereira-Leal, J.B.; Cardoso, J. DNA methylation fingerprint of hepatocellular carcinoma from tissue and liquid biopsies. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, N.; Ushijima, T. Epigenetic impact of infection on carcinogenesis: Mechanisms and applications. Genome Med. 2016, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, A.; Joosten, S.C.; Feng, Z.; de Ruijter, T.C.; Draht, M.X.; Melotte, V.; Smits, K.M.; Veeck, J.; Herman, J.G.; Van Neste, L.; et al. Analysis of DNA methylation in cancer: Location revisited. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Gan, X.; Liu, L.; Yang, Y.; Ding, D.; Li, W.; Jiang, J.; Ding, W.; Zhao, L.; Hou, G.; et al. DNA hypermethylation modification promotes the development of hepatocellular carcinoma by depressing the tumor suppressor gene ZNF334. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irizarry, R.A.; Ladd-Acosta, C.; Wen, B.; Wu, Z.; Montano, C.; Onyango, P.; Cui, H.; Gabo, K.; Rongione, M.; Webster, M.; et al. The human colon cancer methylome shows similar hypo- and hypermethylation at conserved tissue-specific CpG island shores. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thienpont, B.; Steinbacher, J.; Zhao, H.; D’Anna, F.; Kuchnio, A.; Ploumakis, A.; Ghesquiere, B.; Van Dyck, L.; Boeckx, B.; Schoonjans, L.; et al. Tumour hypoxia causes DNA hypermethylation by reducing TET activity. Nature 2016, 537, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, L.A.; Melotte, V.; de Schrijver, J.; de Maat, M.; Smit, V.T.; Bovee, J.V.; French, P.J.; van den Brandt, P.A.; Schouten, L.J.; de Meyer, T.; et al. The CpG island methylator phenotype: What’s in a name? Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 5858–5868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teschendorff, A.E.; Jones, A.; Fiegl, H.; Sargent, A.; Zhuang, J.J.; Kitchener, H.C.; Widschwendter, M. Epigenetic variability in cells of normal cytology is associated with the risk of future morphological transformation. Genome Med. 2012, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teschendorff, A.E.; Widschwendter, M. Differential variability improves the identification of cancer risk markers in DNA methylation studies profiling precursor cancer lesions. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1487–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, J.; Jones, A.; Lee, S.H.; Ng, E.; Fiegl, H.; Zikan, M.; Cibula, D.; Sargent, A.; Salvesen, H.B.; Jacobs, I.J.; et al. The dynamics and prognostic potential of DNA methylation changes at stem cell gene loci in women’s cancer. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Wei, D.; Ji, Y.; Chen, L.; Yang, L.; Li, G.; Wu, L.; Hou, T.; Xie, L.; Ding, G.; et al. Integrative analysis of DNA methylation and gene expression reveals hepatocellular carcinoma-specific diagnostic biomarkers. Genome Med. 2018, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haen, E. Dose-Related Reference Range as a Tool in Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. Ther. Drug Monit. 2022, 44, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.Y.; Li, A.Q.; Shi, H.; Guo, T.K.; Shen, Y.F.; Deng, Y.; Wang, L.T.; Wang, T.; Cai, H. A novel DNA methylation-based model that effectively predicts prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biosci. Rep. 2021, 41, BSR20203945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Zheng, M.; Yang, X.; Huang, H.; Zhao, L. Methylation-associated inactivation of JPH3 and its effect on prognosis and cell biological function in HCC. Mol. Med. Rep. 2022, 25, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Bu, J.; Yu, J.; Jin, M.; Meng, G.; Zhu, X. Comprehensive review and updated analysis of DNA methylation in hepatocellular carcinoma: From basic research to clinical application. Clin. Transl. Med. 2024, 14, e70066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Marek, G.W., 3rd; Hlady, R.A.; Wagner, R.T.; Zhao, X.; Clark, V.C.; Fan, A.X.; Liu, C.; Brantly, M.; Robertson, K.D. Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency Liver Disease, Mutational Homogeneity Modulated by Epigenetic Heterogeneity with Links to Obesity. Hepatology 2019, 70, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshida, Y.; Villanueva, A.; Kobayashi, M.; Peix, J.; Chiang, D.Y.; Camargo, A.; Gupta, S.; Moore, J.; Wrobel, M.J.; Lerner, J.; et al. Gene expression in fixed tissues and outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 1995–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, A.; Portela, A.; Sayols, S.; Battiston, C.; Hoshida, Y.; Mendez-Gonzalez, J.; Imbeaud, S.; Letouze, E.; Hernandez-Gea, V.; Cornella, H.; et al. DNA methylation-based prognosis and epidrivers in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2015, 61, 1945–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Shui, L.; Jia, J.; Wu, C. Construction and Validation of Novel Diagnostic and Prognostic DNA Methylation Signatures for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.C.; Oxnard, G.R.; Klein, E.A.; Swanton, C.; Seiden, M.V.; Consortium, C. Sensitive and specific multi-cancer detection and localization using methylation signatures in cell-free DNA. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revill, K.; Wang, T.; Lachenmayer, A.; Kojima, K.; Harrington, A.; Li, J.; Hoshida, Y.; Llovet, J.M.; Powers, S. Genome-wide methylation analysis and epigenetic unmasking identify tumor suppressor genes in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2013, 145, 1424–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.A.; Tiirikainen, M.; Kwee, S.; Okimoto, G.; Yu, H.; Wong, L.L. Elucidating the landscape of aberrant DNA methylation in hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kgatle, M.M.; Setshedi, M.; Hairwadzi, H.N. Hepatoepigenetic Alterations in Viral and Nonviral-Induced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 3956485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, T.H.; Kim, H.; Oh, B.K.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, K.S.; Jung, G.; Park, Y.N. Aberrant CpG island hypermethylation in dysplastic nodules and early HCC of hepatitis B virus-related human multistep hepatocarcinogenesis. J. Hepatol. 2011, 54, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirov, G.; Rees, E.; Walters, J.T.; Escott-Price, V.; Georgieva, L.; Richards, A.L.; Chambert, K.D.; Davies, G.; Legge, S.E.; Moran, J.L.; et al. The penetrance of copy number variations for schizophrenia and developmental delay. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertson, D.G.; Collins, C.; McCormick, F.; Gray, J.W. Chromosome aberrations in solid tumors. Nat. Genet. 2003, 34, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.M.; Yim, S.H.; Shin, S.H.; Xu, H.D.; Jung, Y.C.; Park, C.K.; Choi, J.Y.; Park, W.S.; Kwon, M.S.; Fiegler, H.; et al. Clinical implication of recurrent copy number alterations in hepatocellular carcinoma and putative oncogenes in recurrent gains on 1q. Int. J. Cancer 2008, 123, 2808–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Rondon, N.; Villegas, V.E.; Rondon-Lagos, M. The Role of Chromosomal Instability in Cancer and Therapeutic Responses. Cancers 2017, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stranger, B.E.; Forrest, M.S.; Dunning, M.; Ingle, C.E.; Beazley, C.; Thorne, N.; Redon, R.; Bird, C.P.; de Grassi, A.; Lee, C.; et al. Relative impact of nucleotide and copy number variation on gene expression phenotypes. Science 2007, 315, 848–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davoli, T.; Uno, H.; Wooten, E.C.; Elledge, S.J. Tumor aneuploidy correlates with markers of immune evasion and with reduced response to immunotherapy. Science 2017, 355, eaaf8399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansregret, L.; Swanton, C. The Role of Aneuploidy in Cancer Evolution. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2017, 7, a028373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorsson, V.; Gibbs, D.L.; Brown, S.D.; Wolf, D.; Bortone, D.S.; Ou Yang, T.H.; Porta-Pardo, E.; Gao, G.F.; Plaisier, C.L.; Eddy, J.A.; et al. The Immune Landscape of Cancer. Immunity 2018, 48, 812–830 e814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassaganyas, L.; Pinyol, R.; Esteban-Fabro, R.; Torrens, L.; Torrecilla, S.; Willoughby, C.E.; Franch-Exposito, S.; Vila-Casadesus, M.; Salaverria, I.; Montal, R.; et al. Copy-Number Alteration Burden Differentially Impacts Immune Profiles and Molecular Features of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 6350–6361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansregret, L.; Vanhaesebroeck, B.; Swanton, C. Determinants and clinical implications of chromosomal instability in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budczies, J.; Seidel, A.; Christopoulos, P.; Endris, V.; Kloor, M.; Gyorffy, B.; Seliger, B.; Schirmacher, P.; Stenzinger, A.; Denkert, C. Integrated analysis of the immunological and genetic status in and across cancer types: Impact of mutational signatures beyond tumor mutational burden. Oncoimmunology 2018, 7, e1526613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Sanchez, A.; Cybulska, P.; Mager, K.L.; Koplev, S.; Cast, O.; Couturier, D.L.; Memon, D.; Selenica, P.; Nikolovski, I.; Mazaheri, Y.; et al. Unraveling tumor-immune heterogeneity in advanced ovarian cancer uncovers immunogenic effect of chemotherapy. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.M.; Shih, J.; Ha, G.; Gao, G.F.; Zhang, X.; Berger, A.C.; Schumacher, S.E.; Wang, C.; Hu, H.; Liu, J.; et al. Genomic and Functional Approaches to Understanding Cancer Aneuploidy. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 676–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusi, F.; Saponara, S.; Valoti, M.; Dragoni, S.; D’Elia, P.; Sgaragli, T.; Alderighi, D.; Kawase, M.; Shah, A.; Motohashi, N.; et al. Cancer cell permeability-glycoprotein as a target of MDR reverters: Possible role of novel dihydropyridine derivatives. Curr. Drug Targets 2006, 7, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.P.; Xu, D.J.; Huang, C.; Wang, W.P.; Xu, W.K. Astragaloside IV reduces the expression level of P-glycoprotein in multidrug-resistant human hepatic cancer cell lines. Mol. Med. Rep. 2014, 9, 2131–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedard, P.L.; Hyman, D.M.; Davids, M.S.; Siu, L.L. Small molecules, big impact: 20 years of targeted therapy in oncology. Lancet 2020, 395, 1078–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Yang, H.; Lin, A.; Xie, J.; Wang, H.; Zhou, J.; Carr, S.R.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. CPADS: A web tool for comprehensive pancancer analysis of drug sensitivity. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumahdi, S.; de Sauvage, F.J. The great escape: Tumour cell plasticity in resistance to targeted therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussinov, R.; Tsai, C.J.; Jang, H. Anticancer drug resistance: An update and perspective. Drug Resist. Updat. 2021, 59, 100796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammut, S.J.; Crispin-Ortuzar, M.; Chin, S.F.; Provenzano, E.; Bardwell, H.A.; Ma, W.; Cope, W.; Dariush, A.; Dawson, S.J.; Abraham, J.E.; et al. Multi-omic machine learning predictor of breast cancer therapy response. Nature 2022, 601, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.C. Targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Thorac. Cancer 2020, 11, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, D.S.; Karthikeyan, S.K.; Korla, P.K.; Patel, H.; Shovon, A.R.; Athar, M.; Netto, G.J.; Qin, Z.S.; Kumar, S.; Manne, U.; et al. UALCAN: An update to the integrated cancer data analysis platform. Neoplasia 2022, 25, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Fu, J.; Zeng, Z.; Cohen, D.; Li, J.; Chen, Q.; Li, B.; Liu, X.S. TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, W509–W514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Li, Y.; Wan, E.; Zhang, E.; Sun, L. Construction of an lncRNA model for prognostic prediction of bladder cancer. BMC Med. Genom. 2022, 15, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.R.; Seo, C.W.; Kim, J. The value of CDC42 effector protein 2 as a novel prognostic biomarker in liver hepatocellular carcinoma: A comprehensive data analysis. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect. 2023, 14, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.J.; Hu, F.F.; Xie, G.Y.; Miao, Y.R.; Li, X.W.; Zeng, Y.; Guo, A.Y. GSCA: An integrated platform for gene set cancer analysis at genomic, pharmacogenomic and immunogenomic levels. Brief. Bioinform. 2023, 24, bbae237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, W.; Kong, L.; Hou, Z.; Ji, H. CD44 is a prognostic biomarker and correlated with immune infiltrates in gastric cancer. BMC Med. Genom. 2022, 15, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Shu, G.; Yin, G. A pan-cancer characterization of immune-related NFIL3 identifies potential predictive biomarker. J. Cancer 2024, 15, 1271–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.A.; Lee, M.H.; Bae, A.N.; Kim, J.; Park, J.H.; Lee, J.H. A Comprehensive Analysis of HOXB13 Expression in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Medicina 2024, 60, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, A.; De Meyer, T.; Jeschke, J.; Van Criekinge, W. MEXPRESS: Visualizing expression, DNA methylation and clinical TCGA data. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Khedkar, S.; Bork, P. SMART: Recent updates, new developments and status in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D458–D460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y.; Su, L.X.; Chen, W.X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.Y.; Shen, Y.C.; You, J.X.; Wang, J.B.; Zhang, L.; Wang, D.; et al. Clinical Implications of Necroptosis Genes Expression for Cancer Immunity and Prognosis: A Pan-Cancer Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 882216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modhukur, V.; Iljasenko, T.; Metsalu, T.; Lokk, K.; Laisk-Podar, T.; Vilo, J. MethSurv: A web tool to perform multivariable survival analysis using DNA methylation data. Epigenomics 2018, 10, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouryahya, M.; Oh, J.H.; Mathews, J.C.; Belkhatir, Z.; Moosmuller, C.; Deasy, J.O.; Tannenbaum, A.R. Pan-Cancer Prediction of Cell-Line Drug Sensitivity Using Network-Based Methods. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.P.; Wiegers, T.C.; Johnson, R.J.; Sciaky, D.; Wiegers, J.; Mattingly, C.J. Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD): Update 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D1257–D1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasaikar, S.V.; Straub, P.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B. LinkedOmics: Analyzing multi-omics data within and across 32 cancer types. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D956–D963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Li, M.; Wei, J.; Chen, S.; Xue, C.; Duan, Y.; Tang, F.; Li, G.; Xiong, W.; She, K.; et al. NOP2/Sun RNA methyltransferase 2 is a potential pan-cancer prognostic biomarker and is related to immunity. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.H.; Hou, A.J.; Zhang, S.H.; Dong, J.J.; Kuang, H.X.; Yang, L.; Jiang, H. WGCNA combined with machine learning to find potential biomarkers of liver cancer. Medicine 2023, 102, e36536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: Protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Clinicopathological Characteristics | Overall Survival | Relapse-Free Survival | Progression-Free Survival | Disease-Specific Survival | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 364) | (n = 316) | (n = 370) | (n = 362) | |||||||||

| N | Hazard Ratio | p-Value | N | Hazard Ratio | p-Value | N | Hazard Ratio | p-Value | N | Hazard Ratio | p-Value | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 246 | 1.49 (0.95–2.33) | 0.08 | 210 | 1.47 (0.98–2.18) | 0.059 | 249 | 1.65 (1.15–2.37) | 0.0059 | 244 | 1.92 (1.07–3.45) | 0.027 |

| Female | 118 | 1.11 (0.63–1.96) | 0.71 | 106 | 1.82 (1–3.33) | 0.048 | 121 | 1.96 (1.16–3.3) | 0.01 | 118 | 1.02 (0.49–2.1) | 0.96 |

| Stage | ||||||||||||

| I | 170 | 1.39 (0.75–2.56) | 0.29 | 153 | 1.65 (0.95–2.84) | 0.071 | 171 | 1.7 (1.03–2.81) | 0.036 | 168 | 2.04 (0.82–5.1) | 0.12 |

| I + II | 253 | 1.39 (0.85–2.26) | 0.19 | 228 | 1.52 (1–2.31) | 0.05 | 256 | 1.79 (1.22–2.63) | 0.0026 | 251 | 2.12 (1.02–4.39) | 0.04 |

| II | 83 | 1.54 (0.69–3.42) | 0.29 | 75 | 1.22 (0.62–2.4) | 0.56 | 85 | 1.71 (0.93–3.15) | 0.083 | 83 | 3.33 (0.92–12.13) | 0.052 |

| II + III | 166 | 1.51 (0.94–2.44) | 0.087 | 145 | 1.48 (0.95–2.32) | 0.084 | 170 | 1.57 (1.05–2.34) | 0.027 | 166 | 2.09 (1.12–3.91) | 0.018 |

| III | 83 | 1.85 (1.02–3.36) | 0.039 | 70 | 1.37 (0.75–2.51) | 0.3 | 85 | 1.82 (1.05–3.16) | 0.029 | 83 | 2.22 (1.08–4.59) | 0.027 |

| III + IV | 87 | 1.82 (1.03–3.23) | 0.037 | 70 | 1.37 (0.75–2.51) | 0.3 | 90 | 1.81 (1.06–3.07) | 0.027 | 87 | 2.01 (1–4.02) | 0.044 |

| IV | 4 | - | - | 0 | - | - | 5 | - | - | 3 | - | - |

| Grade | ||||||||||||

| I | 55 | 1.63 (0.64–4.15) | 0.3 | 45 | 2.16 (0.81–5.72) | 0.11 | 55 | 1.73 (0.79–3.77) | 0.17 | 55 | 0.75 (0.21–2.59) | 0.64 |

| II | 174 | 1.55 (0.92–2.61) | 0.099 | 149 | 1.68 (1.03–2.74) | 0.036 | 177 | 1.95 (1.25–3.02) | 0.0025 | 171 | 2.27 (1.13–4.58) | 0.019 |

| III | 118 | 1.48 (0.81–2.74) | 0.2 | 107 | 1.29 (0.75–2.21) | 0.35 | 121 | 1.67 (1–2.78) | 0.048 | 119 | 1.99 (0.89–4.44) | 0.086 |

| IV | 12 | - | - | 11 | - | - | 12 | - | - | 12 | - | - |

| AJCC_T | ||||||||||||

| I | 180 | 1.67 (0.92–3.02) | 0.087 | 160 | 1.74 (1.02–2.97) | 0.039 | 181 | 1.84 (1.13–3) | 0.013 | 178 | 2.11 (0.91–4.89) | 0.074 |

| II | 90 | 1.65 (0.78–3.5) | 0.19 | 80 | 1.16 (0.61–2.19) | 0.65 | 93 | 1.75 (0.99–3.08) | 0.05 | 91 | 2.4 (0.84–6.82) | 0.09 |

| III | 78 | 1.37 (0.75–2.5) | 0.3 | 67 | 1.35 (0.72–2.53) | 0.34 | 80 | 1.65 (0.93–2.91) | 0.081 | 77 | 1.6 (0.76–3.35) | 0.21 |

| IV | 13 | - | - | 6 | - | - | 13 | - | - | 13 | - | - |

| Vascular invasion | ||||||||||||

| None | 203 | 1.7 (1–2.89) | 0.047 | 175 | 1.57 (0.97–2.55) | 0.064 | 205 | 1.68 (1.07–2.64) | 0.022 | 201 | 2.27 (1.05–4.88) | 0.032 |

| Micro | 90 | 1.03 (0.47–2.22) | 0.95 | 82 | 1.32 (0.7–2.49) | 0.4 | 92 | 1.49 (0.84–2.65) | 0.17 | 90 | 1.17 (0.39–3.5) | 0.77 |

| Macro | 16 | - | - | 14 | - | - | 16 | - | - | 14 | - | - |

| Race | ||||||||||||

| White | 181 | 1.2 (0.75–1.91) | 0.45 | 147 | 1.65 (1.05–2.61) | 0.029 | 184 | 1.84 (1.24–2.73) | 0.0023 | 179 | 1.12 (0.64–1.98) | 0.69 |

| Asian | 155 | 3.09 (1.62–5.92) | 0.00033 | 145 | 1.33 (0.8–2.21) | 0.27 | 157 | 1.55 (0.96–2.48) | 0.068 | 154 | 4.31 (1.72–10.82) | 0.00068 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 115 | 1.34 (0.72–2.5) | 0.36 | 99 | 1.23 (0.69–2.21) | 0.48 | 117 | 1.53 (0.91–2.56) | 0.11 | 117 | 1.24 (0.6–2.57) | 0.56 |

| None | 202 | 1.5 (0.94–2.38) | 0.084 | 183 | 1.78 (1.13–2.79) | 0.011 | 205 | 1.94 (1.29–2.92) | 0.0012 | 199 | 2.5 (1.29–4.84) | 0.0048 |

| Hepatitis virus | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 150 | 1.99 (1.02–3.86) | 0.039 | 139 | 1.13 (0.69–1.86) | 0.62 | 153 | 1.32 (0.83–2.09) | 0.24 | 151 | 2.9 (1.19–7.07) | 0.014 |

| None | 167 | 1.17 (0.74–1.85) | 0.49 | 143 | 1.7 (1.03–2.81) | 0.036 | 169 | 1.96 (1.26–3.05) | 0.0022 | 165 | 1.12 (0.62–2) | 0.71 |

| Dataset | Cancer Type | Endpoint | N | In (HRhigh/HRlow) | Cox p-Value | HR (95% Cllow—Clup) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE13507 | Bladder cancer | Disease-specific survival | 165 | 1.05 | 0.002101 | 4.48 (1.72–11.66) |

| GSE12276 | Breast cancer | Relapse-free survival | 204 | 0.65 | 0.004341 | 1.26 (1.08–1.48) |

| GSE31210 | Lung cancer | Relapse-free survival | 204 | −1.85 | 0.019986 | 0.76 (0.60–0.96) |

| GSE4475 | Blood cancer | Overall survival | 158 | 0.77 | 0.020094 | 7.65 (1.38–42.49) |

| GSE1379 | Breast cancer | Relapse-free survival | 60 | 2.1 | 0.024794 | 1.83 (1.08–3.10) |

| GSE1378 | Breast cancer | Relapse-free survival | 60 | 1.31 | 0.031161 | 1.51 (1.04–2.18) |

| GSE8970 | Blood cancer | Overall survival | 34 | 1.28 | 0.046263 | 1.80 (1.01–3.22) |

| E-TABM-158 | Breast cancer | Relapse-free survival | 117 | −1.72 | 0.04948 | 0.11 (0.01–1.00) |

| Gene | Probe | Chr | Position | Average of Cancer Sample | Average of Normal Sample | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BFSP1 | cg27500292 | chr20 | 17525532 | 0.62 | 0.78 | <0.001 |

| cg06521030 | chr20 | 17528778 | 0.89 | 0.93 | <0.001 | |

| cg00412842 | chr20 | 17530834 | 0.09 | 0.18 | <0.001 | |

| cg07217075 | chr20 | 17531181 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| cg07904983 | chr20 | 17531343 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| cg26371206 | chr20 | 17531563 | 0.1 | 0.17 | <0.001 | |

| cg04346572 | chr20 | 17531649 | 0.08 | 0.19 | <0.001 | |

| cg23985077 | chr20 | 17532007 | 0.72 | 0.89 | <0.001 | |

| cg23032598 | chr20 | 17532150 | 0.76 | 0.85 | <0.001 | |

| cg02795691 | chr20 | 17533752 | 0.52 | 0.68 | <0.001 | |

| cg18815565 | chr20 | 17559363 | 0.81 | 0.92 | <0.001 | |

| cg04264633 | chr20 | 17559916 | 0.42 | 0.49 | <0.001 | |

| cg14801864 | chr20 | 17560330 | 0.68 | 0.8 | <0.001 | |

| cg22276571 | chr20 | 17568954 | 0.15 | 0.21 | <0.001 | |

| cg10573932 | chr20 | 17569052 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.008 | |

| cg23651728 | chr20 | 17530765 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.6 | |

| cg04263118 | chr20 | 17531532 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.3 | |

| cg14158573 | chr20 | 17569037 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.9 | |

| cg19765886 | chr20 | 17569220 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.07 | |

| cg03925157 | chr20 | 17569310 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.08 | |

| cg00473384 | chr20 | 17569793 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.08 | |

| cg11320690 | chr20 | 17569829 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.3 | |

| cg12878213 | chr20 | 17569836 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.2 | |

| cg06260159 | chr20 | 17569935 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.8 | |

| cg01993865 | chr20 | 17570045 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1 | |

| cg13462232 | chr20 | 17570521 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.5 |

| Gene | Probe | Chr | Position | G1 Beta Average | G2 Beta Average | G3 Beta Average | G4 Beta Average | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BFSP1 | cg27500292 | chr20 | 17525532 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.6 | 0.55 | 0.0005 |

| cg06521030 | chr20 | 17528778 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.87 | ||

| cg23651728 | chr20 | 17530765 | 0.08 | 0.1 | 0.09 | 0.07 | ||

| cg00412842 | chr20 | 17530834 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.07 | 0.06 | ||

| cg07217075 | chr20 | 17531181 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | ||

| cg07904983 | chr20 | 17531343 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||

| cg04263118 | chr20 | 17531532 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.04 | ||

| cg26371206 | chr20 | 17531563 | 0.1 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.08 | ||

| cg04346572 | chr20 | 17531649 | 0.1 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | ||

| cg23985077 | chr20 | 17532007 | 0.8 | 0.72 | 0.7 | 0.59 | ||

| cg23032598 | chr20 | 17532150 | 0.8 | 0.78 | 0.73 | 0.65 | ||

| cg02795691 | chr20 | 17533752 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.37 | ||

| cg18815565 | chr20 | 17559363 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.82 | 0.8 | ||

| cg04264633 | chr20 | 17559916 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.45 | ||

| cg14801864 | chr20 | 17560330 | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.64 | ||

| cg22276571 | chr20 | 17568954 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.11 | ||

| cg14158573 | chr20 | 17569037 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.11 | ||

| cg10573932 | chr20 | 17569052 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.12 | ||

| cg19765886 | chr20 | 17569220 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||

| cg03925157 | chr20 | 17569310 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.12 | ||

| cg00473384 | chr20 | 17569793 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||

| cg11320690 | chr20 | 17569829 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||

| cg12878213 | chr20 | 17569836 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | ||

| cg06260159 | chr20 | 17569935 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | ||

| cg01993865 | chr20 | 17570045 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | ||

| cg13462232 | chr20 | 17570521 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Cancer | Gene | Type | Cell Type | R | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIHC | BFSP1 | Expression | Bcell | 0.46 | <0.001 |

| nTreg | 0.21 | <0.001 | |||

| Tr1 | 0.21 | <0.001 | |||

| CD8-T | 0.16 | <0.001 | |||

| CD8-naïve | 0.16 | <0.001 | |||

| NKT | 0.15 | <0.001 | |||

| MAIT | −0.33 | <0.001 | |||

| Macrophage | −0.29 | <0.001 | |||

| Monocyte | −0.25 | <0.001 | |||

| Tfh | −0.2 | <0.001 | |||

| CD4_naïve | −0.19 | <0.001 | |||

| Th17 | −0.17 | <0.001 | |||

| NK | −0.16 | <0.001 | |||

| CNV | Bcell | 0.18 | <0.001 | ||

| nTreg | 0.13 | 0.01 | |||

| CD8_T | 0.14 | 0.006 | |||

| Th1 | 0.12 | 0.02 | |||

| CD4_naïve | −0.18 | 0 | |||

| MAIT | −0.17 | <0.001 | |||

| Th17 | −0.13 | 0.02 | |||

| Monocyte | −0.13 | 0.02 | |||

| Methylation | Tfh | 0.31 | <0.001 | ||

| CD4_T | 0.28 | <0.001 | |||

| MAIT | 0.25 | <0.001 | |||

| NK | 0.22 | <0.001 | |||

| Th1 | 0.18 | <0.001 | |||

| iTreg | 0.14 | 0.008 | |||

| Macrophage | 0.13 | 0.01 | |||

| CD8_T | 0.13 | 0.01 | |||

| NKT | 0.13 | 0.01 | |||

| Neutrophil | −0.27 | <0.001 | |||

| Bcell | −0.27 | <0.001 | |||

| Tr1 | −0.15 | 0.003 | |||

| Th17 | −0.11 | 0.03 |

| Chemical Name | ID | Interaction Actions |

|---|---|---|

| 2,3′,4,4′,5-Pentachlorobiphenyl | C070055 | Increases expression |

| 2,3,5-Trichloro-6-phenyl-(1,4)benzoquinone | C587734 | Increases expression |

| Acetamide | C030686 | Increases expression |

| Afuresertib | C000593263 | Increases expression |

| Aristolochic acid | C000228 | Increases expression |

| Benzo(b)fluoranthene | C006703 | Increases expression |

| Copper sulfate | D019327 | Increases expression |

| ethyl-p-hydroxybenzoate | C012313 | Increases expression |

| Fenvalerate | C017690 | Increases expression |

| Folic acid | D005492 | Increases expression |

| Gentamicins | D005839 | Increases expression |

| Hexachlorocyclohexane | D001556 | Increases expression |

| (+)-JQ1 compound | C561695 | Increases expression |

| Lipopolysaccharides | D008070 | Increases expression |

| Methamphetamine | D008694 | Increases expression |

| Particulate matter | D052638 | Increases expression |

| Propylthiouracil | D011441 | Increases expression |

| S-(1,2-Dichlorovinyl)cysteine | C039961 | Increases expression |

| S-(1,2-Dichlorovinyl)cysteine | C039961 | Increases expression |

| Sodium arsenite | C017947 | Increases expression |

| Tetrachlorodibenzodioxin | D013749 | Increases expression |

| Thioacetamide | D013853 | Increases expression |

| Trichloroethylene | D014241 | Increases expression |

| Triptolide | C001899 | Increases expression |

| Triptonide | C084079 | Increases expression |

| Vinclozolin | C025643 | Increases expression |

| Acetaminophen | D000082 | Decreases expression |

| Acrylamide | D020106 | Decreases expression |

| Ammonium 2,3,3,3-tetrafluoro-2- (heptafluoropropoxy)-propanoate | C000611729 | Decreases expression |

| Belinostat | C487081 | Decreases expression |

| Bilirubin | D001663 | Decreases expression |

| bisphenol A | C006780 | Decreases expression |

| Dichlorodiphenyl dichloroethylene | D003633 | Decreases expression |

| Dietary fats | D004041 | Decreases expression |

| Dinophysistoxin 1 | C051904 | Decreases expression |

| Domoic acid | C012301 | Decreases expression |

| ICG 001 | C492448 | Decreases expression |

| Sunitinib | D000077210 | Decreases expression |

| Testosterone | D013739 | Decreases expression |

| Thalidomide | D013792 | Decreases expression |

| Tobacco smoke pollution | D014028 | Decreases expression |

| Tretinoin | D014212 | Decreases expression |

| Zinc sulfate | D019287 | Decreases expression |

| Zoledronic acid | D000077211 | Decreases expression |

| Gene | Similarity Index | Common Interaction Chemicals |

|---|---|---|

| CCDC88B | 0.2784 | 27 |

| CCDC102A | 0.2747 | 25 |

| OLFM2 | 0.2727 | 24 |

| SYTL3 | 0.2708 | 26 |

| CPNE5 | 0.2673 | 27 |

| LYL1 | 0.266 | 25 |

| MGAM | 0.2655 | 30 |

| PRX | 0.2626 | 26 |

| SHANK1 | 0.2621 | 27 |

| KCTD13 | 0.2604 | 25 |

| PLEKHA4 | 0.26 | 26 |

| ANKS6 | 0.2558 | 22 |

| SH3RF2 | 0.2547 | 27 |

| KCNAB1 | 0.2542 | 30 |

| KCNH4 | 0.2533 | 19 |

| CASS4 | 0.2529 | 22 |

| C5AR2 | 0.2526 | 24 |

| MPDU1 | 0.2526 | 24 |

| ARHGAP27 | 0.2524 | 26 |

| NPTXR | 0.2524 | 26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, K.-S.; Kim, J. Multi-Omics and Functional Analysis of BFSP1 as a Prognostic and Therapeutic Target in Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Medicina 2025, 61, 2196. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122196

Lee K-S, Kim J. Multi-Omics and Functional Analysis of BFSP1 as a Prognostic and Therapeutic Target in Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2196. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122196

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Kyu-Shik, and Jongwan Kim. 2025. "Multi-Omics and Functional Analysis of BFSP1 as a Prognostic and Therapeutic Target in Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2196. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122196

APA StyleLee, K.-S., & Kim, J. (2025). Multi-Omics and Functional Analysis of BFSP1 as a Prognostic and Therapeutic Target in Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Medicina, 61(12), 2196. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122196