Plasma Exchange as an Adjunctive Therapeutic Option for Severe and Refractory Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-Negative Microscopic Polyangiitis and Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

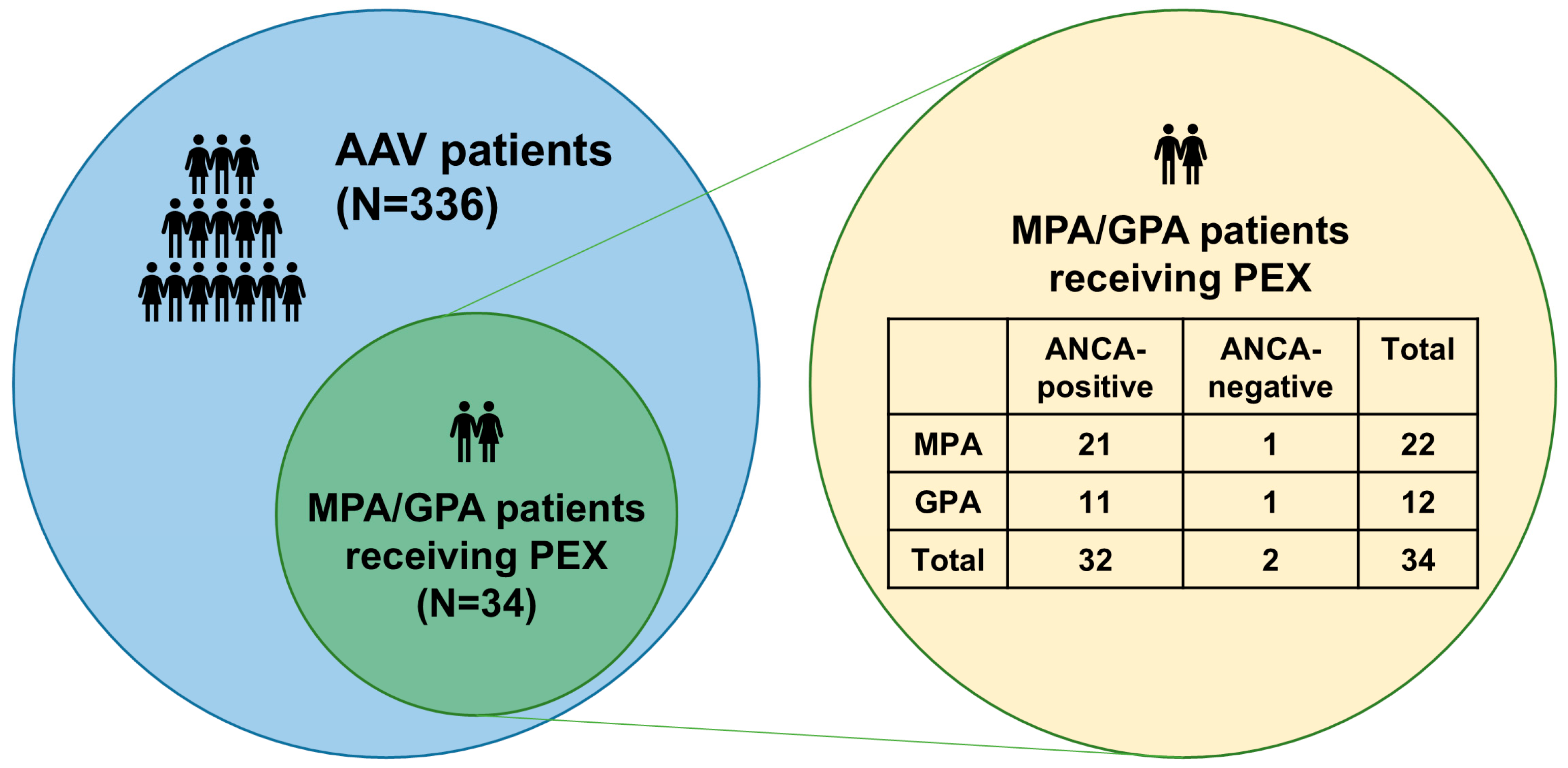

2.1. Patients

- Patients whose first diagnosis of MPA/GPA was made at this hospital.

- Patients whose medical records were sufficiently detailed to allow collection of clinical data at AAV diagnosis and during follow-up.

- Patients for whom ANCA test results at AAV diagnosis and at the time of PEX were available [18].

- Patients who had not received immunosuppressive drugs for the treatment of MPA/GPA before diagnosis.

- Patients who had not received glucocorticoid at a prednisolone dose greater than 10 mg/day within four weeks before diagnosis.

- Patients who were followed up for at least three months after diagnosis.

2.2. Ethical Disclosure

2.3. ANCA Measurements and Accepted Values

2.4. Variables at Diagnosis

2.5. Variables During Follow-Up

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Data at MPA/GPA Diagnosis

3.2. Clinical Data During Follow-Up

3.3. Comparison of Clinical Data at AAV Diagnosis and During Follow-Up Between ANCA-Positive and ANCA-Negative MPA/GPA Patients Receiving PEX

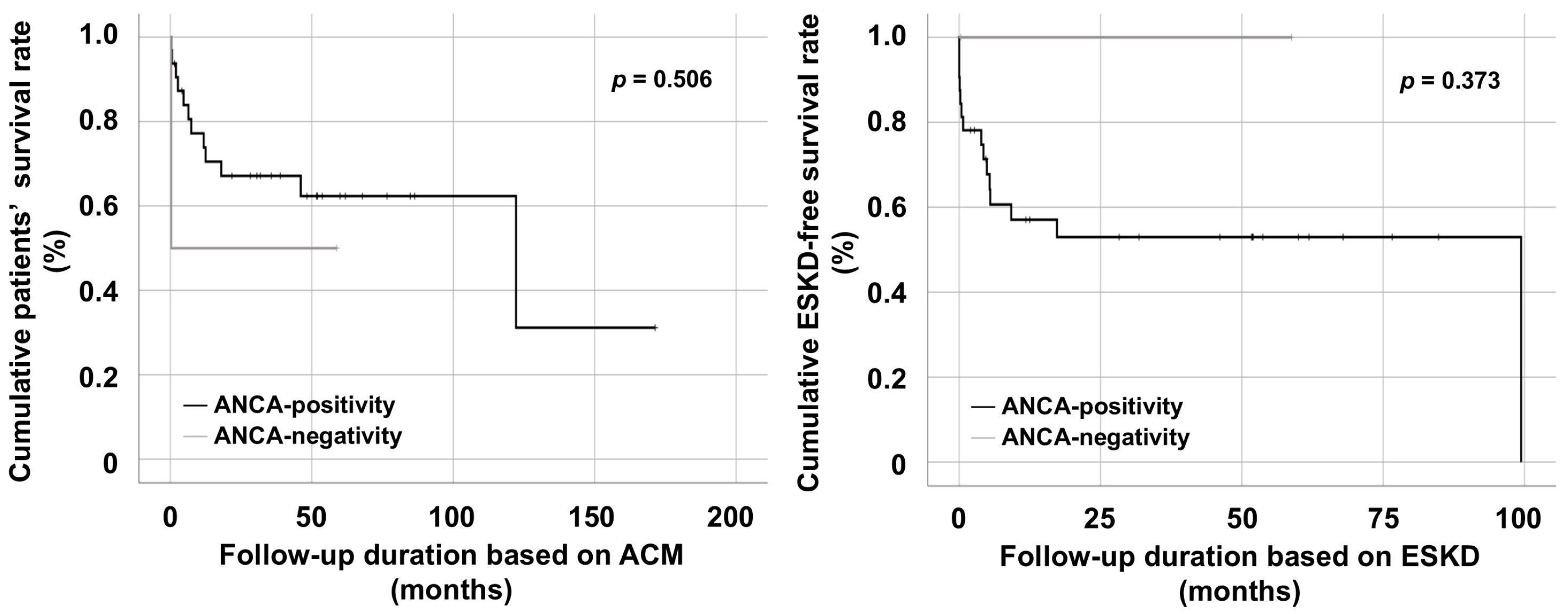

3.4. Comparison of Cumulative Survival Rates Between ANCA-Positive and ANCA-Negative MPA/GPA Patients Receiving PEX

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jennette, J.C.; Falk, R.J.; Bacon, P.A.; Basu, N.; Cid, M.C.; Ferrario, F.; Flores-Suarez, L.F.; Gross, W.L.; Guillevin, L.; Hagen, E.C.; et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 65, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, R.; Lane, S.; Hanslik, T.; Hauser, T.; Hellmich, B.; Koldingsnes, W.; Mahr, A.; Segelmark, M.; Cohen-Tervaert, J.W.; Scott, D. Development and validation of a consensus methodology for the classification of the ANCA-associated vasculitides and polyarteritis nodosa for epidemiological studies. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2007, 66, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triggianese, P.; D’Antonio, A.; Nesi, C.; Kroegler, B.; Di Marino, M.; Conigliaro, P.; Modica, S.; Greco, E.; Nucci, C.; Bergamini, A.; et al. Subclinical microvascular changes in ANCA-vasculitides: The role of optical coherence tomography angiography and nailfold capillaroscopy in the detection of dis-ease-related damage. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2023, 18, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Screm, G.; Gandin, I.; Mondini, L.; Cifaldi, R.; Confalonieri, P.; Bozzi, C.; Salton, F.; Bandini, G.; Monteleone, G.; Hughes, M.; et al. Evaluation of Nailfold Capillaroscopy as a Novel Tool in the Assessment of Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppiah, R.; Robson, J.C.; Grayson, P.C.; Ponte, C.; Craven, A.; Khalid, S.; Judge, A.; Hutchings, A.; Merkel, P.A.; Luqmani, R.A.; et al. 2022 American College of Rheumatology/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology classification criteria for microscopic polyangiitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2022, 81, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, J.C.; Grayson, P.C.; Ponte, C.; Suppiah, R.; Craven, A.; Judge, A.; Khalid, S.; Hutchings, A.; Luqmani, R.A.; A Watts, R.; et al. 2022 American College of Rheumatology/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology classification criteria for granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2022, 81, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyo, J.Y.; Lee, L.E.; Park, Y.B.; Lee, S.W. Comparison of the 2022 ACR/EULAR Classification Criteria for Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-Associated Vasculitis with Previous Criteria. Yonsei Med. J. 2023, 64, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.A.; Langford, C.A.; Maz, M.; Abril, A.; Gorelik, M.; Guyatt, G.; Archer, A.M.; Conn, D.L.; Full, K.A.; Grayson, P.C.; et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology/Vasculitis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-Associated Vasculitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021, 73, 1366–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmich, B.; Sanchez-Alamo, B.; Schirmer, J.H.; Berti, A.; Blockmans, D.; Cid, M.C.; Holle, J.U.; Hollinger, N.; Karadag, O.; Kronbichler, A.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of ANCA-associated vasculitis: 2022 update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2024, 83, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitching, A.R.; Anders, H.J.; Basu, N.; Brouwer, E.; Gordon, J.; Jayne, D.R.; Kullman, J.; Lyons, P.A.; Merkel, P.A.; Savage, C.O.; et al. ANCA-associated vasculitis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Geest, K.S.M.; Brouwer, E.; Sanders, J.S.; Sandovici, M.; Bos, N.A.; Boots, A.M.H.; Abdulahad, W.H.; Stegeman, C.A.; Kallenberg, C.G.M.; Heeringa, P.; et al. Towards precision medicine in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Rheumatology 2018, 57, 1332–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, M.; Watts, R.A.; Bajema, I.M.; Cid, M.C.; Crestani, B.; Hauser, T.; Hellmich, B.; Holle, J.U.; Laudien, M.; Little, M.A.; et al. EULAR/ERA-EDTA recommendations for the management of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2016, 75, 1583–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiakas, S.; Marinaki, S.; Lionaki, S.; Boletis, J. Plasma Exchange in ANCA-Associated Vasculitis: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M.; Merkel, P.A.; Peh, C.A.; Szpirt, W.M.; Puéchal, X.; Fujimoto, S.; Hawley, C.M.; Khalidi, N.; Floßmann, O.; Wald, R.; et al. Plasma Exchange and Glucocorticoids in Severe ANCA-Associated Vasculitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M.; Collister, D.; Zeng, L.; Merkel, P.A.; Pusey, C.D.; Guyatt, G.; Peh, C.A.; Szpirt, W.; Ito-Hara, T.; Jayne, D.R.W.; et al. The effects of plasma exchange in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2022, 376, e064604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, P.; Cipriani, L.; Viazzi, F. Plasma Exchange and Glucocorticoids in Severe ANCA-Associated Vasculitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2168–2169. [Google Scholar]

- Odler, B.; Riedl, R.; Geetha, D.; Szpirt, W.M.; Hawley, C.; Uchida, L.; Wallace, Z.S.; Walters, G.; Muso, E.; Tesar, V.; et al. The effects of plasma exchange and glucocorticoids on early kidney function among patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis in the PEXIVAS trial. Kidney Int. 2025, 107, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossuyt, X.; Cohen Tervaert, J.W.; Arimura, Y.; Blockmans, D.; Flores-Suárez, L.F.; Guillevin, L.; Hellmich, B.; Jayne, D.; Jennette, J.C.; Kallenberg, C.G.; et al. Position paper: Revised 2017 international consensus on testing of ANCAs in granulomatosis with polyangiitis and microscopic polyangiitis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2017, 13, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phatak, S.; Aggarwal, A.; Agarwal, V.; Lawrence, A.; Misra, R. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) testing: Audit from a clinical immunology laboratory. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 20, 774–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiseev, S.; Cohen Tervaert, J.W.; Arimura, Y.; Bogdanos, D.P.; Csernok, E.; Damoiseaux, J.; Ferrante, M.; Flores-Suárez, L.F.; Fritzler, M.J.; Invernizzi, P.; et al. 2020 international consensus on ANCA testing beyond systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2020, 19, 102618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAdoo, S.P.; Medjeral-Thomas, N.; Gopaluni, S.; Tanna, A.; Mansfield, N.; Galliford, J.; Griffith, M.; Levy, J.; Cairns, T.D.; Jayne, D.; et al. Long-term follow-up of a combined rituximab and cyclophosphamide regimen in renal anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody-associated vasculitis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2019, 34, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtyar, C.; Lee, R.; Brown, D.; Carruthers, D.; Dasgupta, B.; Dubey, S.; Flossmann, O.; Hall, C.; Hollywood, J.; Jayne, D.; et al. Modification and validation of the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (version 3). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2009, 68, 1827–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillevin, L.; Pagnoux, C.; Seror, R.; Mahr, A.; Mouthon, L.; Toumelin, P.L. French Vasculitis Study Group. The Five-Factor Score revisited: Assessment of prognoses of systemic necrotizing vasculitides based on the French Vasculitis Study Group (FVSG) cohort. Medicine 2011, 90, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.W.; Lee, E.J.; Iwaya, T.; Kataoka, H.; Kohzuki, M. Development of the Korean version of Short-Form 36-Item Health Survey: Health related QOL of healthy elderly people and elderly patients in Korea. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2004, 203, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtyar, C.; Flossmann, O.; Hellmich, B.; Bacon, P.; Cid, M.; Cohen-Tervaert, J.W.; Gross, W.L.; Guillevin, L.; Jayne, D.; Mahr, A.; et al. Outcomes from studies of antineutrophil cytoplasm antibody associated vasculitis: A systematic review by the European League Against Rheumatism systemic vasculitis task force. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2008, 67, 1004–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fussner, L.A.; Flores-Suárez, L.F.; Cartin-Ceba, R.; Specks, U.; Cox, P.G.; Jayne, D.R.W.; Gross, W.L.; Guillevin, L.; Jayne, D.; Mahr, A.; et al. Alveolar Hemorrhage in Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-Associated Vasculitis: Results of an International Randomized Controlled Trial (PEXIVAS). Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 209, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, A.C.; Nagler, E.V.; Morton, R.L.; Masson, P. Chronic Kidney Disease. Lancet 2017, 389, 1238–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, D.A.; Wei, K.; Merola, J.F.; O’Brien, W.R.; Takvorian, S.U.; Dellaripa, P.F.; Schur, P.H. Myeloperoxidase-antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies (MPO-ANCA) and Proteinase 3-ANCA without Immunofluorescent ANCA Found by Routine Clinical Testing. J. Rheumatol. 2015, 42, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, A.J.; Ooi, J.D.; Hess, J.J.; van Timmeren, M.M.; Berg, E.A.; Poulton, C.E.; McGregor, J.; Burkart, M.; Hogan, S.L.; Hu, Y.; et al. Epitope specificity determines pathogenicity and detectability in ANCA-associated vasculitis. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 1773–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, A.; Stahl, K.; Seeliger, B.; Wendel-Garcia, P.D.; Lehmann, F.; Schmidt, J.J.; Schmidt, B.M.W.; Welte, T.; Peukert, K.; Wild, L.; et al. The effect of therapeutic plasma exchange on the inflammatory response in septic shock: A secondary analysis of the EXCHANGE-1 trial. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2025, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rony, R.M.I.K.; Shokrani, A.; Malhi, N.K.; Hussey, D.; Mooney, R.; Chen, Z.B.; Scott, T.; Han, H.; Moore, J.; Liu, J.; et al. Therapeutic Plasma Exchange: Current and Emerging Applications to Mitigate Cellular Signaling in Disease. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervantes, C.E.; Bloch, E.M.; Sperati, C.J. Therapeutic Plasma Exchange: Core Curriculum 2023. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2023, 81, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.W.; Ohrr, H.; Shin, S.A.; Yi, J.J. Sex-age-specific association of body mass index with all-cause mortality among 12.8 million Korean adults: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 44, 1696–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.M.; Jung, J.H.; Yang, Y.S.; Kim, W.; Cho, I.Y.; Lee, Y.B.; Park, K.-Y.; Nam, G.E.; Han, K.; Taskforce Team of the Obesity Fact Sheet of the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity. 2023 Obesity Fact Sheet: Prevalence of Obesity and Abdominal Obesity in Adults, Adolescents, and Children in Korea from 2012 to 2021. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2024, 33, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, B.; Han, K.; Ahn, J. On behalf of the Committee of Public Relations of the Korean Society of Lipid and Atherosclerosis. Dyslipidemia Fact Sheet in South Korea, 2024. J. Lipid. Atheroscler. 2025, 14, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDade, T.W.; Meyer, J.M.; Koning, S.M.; Harris, K.M. Body mass and the epidemic of chronic inflammation in early mid-adulthood. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 281, 114059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| At AAV diagnosis | |

| Demographic data | |

| Age (years) | 67.0 (55.5–73.5) |

| Male sex (N, (%)) | 15 (44.1) |

| Female sex (N, (%)) | 19 (55.9) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.1 (19.9–24.8) |

| Ex-smoker | 1 (2.9) |

| Comorbidities (N, (%)) | |

| T2DM | 6 (17.6) |

| Hypertension | 15 (44.1) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 8 (23.5) |

| AAV subtype (N, (%)) | |

| MPA | 22 (64.7) |

| GPA | 12 (35.3) |

| ANCA type and positivity (N, (%)) | |

| MPO-ANCA (or P-ANCA) positivity | 25 (73.5) |

| PR3-ANCA (or C-ANCA) positivity | 7 (20.6) |

| Both ANCAs | 0 (0) |

| No ANCA | 2 (5.9) |

| AAV-specific indices | |

| BVAS | 18.0 (12.0–23.0) |

| FFS | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) |

| SF-36 PCS | 35.8 (18.4–45.3) |

| SF-36 MCS | 37.5 (25.2–54.3) |

| Major organ involvements based on BVAS items (N, (%)) | |

| General symptoms | 19 (55.9) |

| Skin | 3 (8.8) |

| Mucosa and eyes | 1 (2.9) |

| Ears, nose, and throat | 15 (44.1) |

| Lungs | 30 (88.2) |

| Heart | 6 (17.6) |

| Abdomen | 1 (2.9) |

| Kidneys | 29 (85.3) |

| CNS/PNS | 6 (17.6) |

| Laboratory results | |

| White blood cell count (/mm3) | 11,365.0 (7002.5–14,155.0) |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.1 (8.2–10.7) |

| Platelet count (×1000/mm3) | 262.5 (204.0–390.0) |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 111.5 (91.0–142.3) |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 36.6 (21.1–55.3) |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 2.5 (1.2–5.4) |

| Serum total protein (g/dL) | 6.0 (5.4–6.7) |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.2 (2.8–3.6) |

| ESR (mm/hr) | 63.5 (12.5–115.3) |

| CRP (mg/L) | 44.9 (7.2–95.4) |

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Reasons for considering PEX (N, (%)) | |

| DAH | 6 (17.6) |

| RPGN | 28 (82.4) |

| Poor outcomes | |

| ACM (N, (%)) | 13 (38.2) |

| Follow-up duration based on ACM (months) | 33.8 (6.0–59.1) |

| ESKD (N, (%)) | 15 (44.1) |

| Follow-up duration based on ESKD (months) | 10.5 (1.7–52.4) |

| Medications administered (N, (%)) | |

| GC | 34 (100) |

| RTX | 15 (44.1) |

| CYC | 28 (82.4) |

| MMF | 22 (64.7) |

| AZA | 16 (47.1) |

| TAC | 4 (11.8) |

| MTX | 3 (8.8) |

| Variables | ANCA-Positive MPA/GPA Patients (N = 32) | ANCA-Negative MPA/GPA Patients (N = 2) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| At AAV diagnosis | |||

| Demographic data | |||

| Age (years) | 69.0 (12.5) | 61.0 (N/A) | 0.913 |

| Male sex (N, (%)) | 14 (43.8) | 1 (50.0) | 1.000 |

| Female sex (N, (%)) | 18 (56.3) | 1 (50.0) | 1.000 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.8 (4.2) | 25.6 (N/A) | 0.187 |

| Ex-smoker | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Comorbidities (N, (%)) | |||

| T2DM | 6 (18.8) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Hypertension | 15 (46.9) | 0 (0) | 0.492 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 8 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| AAV subtype (N, (%)) | 1.000 | ||

| MPA | 21 (65.6) | 1 (50.0) | |

| GPA | 11 (34.4) | 1 (50.0) | |

| ANCA type and positivity (N, (%)) | |||

| MPO-ANCA (or P-ANCA) positivity | 25 (78.1) | 0 (0) | 0.064 |

| PR3-ANCA (or C-ANCA) positivity | 7 (21.9) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| AAV-specific indices | |||

| BVAS | 18.0 (8.0) | 19.0 (N/A) | 0.741 |

| FFS | 2.0 (1.0) | 2.0 (0) | 0.618 |

| SF-36 PCS | 36.3 (25.3) | 20.0 (N/A) | 0.197 |

| SF-36 MCS | 36.9 (29.6) | 28.8 (N/A) | 0.533 |

| Major organ involvements based on BVAS items (N, (%)) | |||

| General symptoms | 18 (56.3) | 1 (50.0) | 1.000 |

| Skin | 2 (6.3) | 1 (50.0) | 0.171 |

| Mucosa and eyes | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Ears, nose, and throat | 14 (43.8) | 1 (50.0) | 1.000 |

| Lungs | 28 (87.5) | 2 (100) | 1.000 |

| Heart | 6 (18.8) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Abdomen | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Kidneys | 27 (84.4) | 2 (100) | 1.000 |

| CNS/PNS | 5 (15.6) | 1 (50.0) | 0.326 |

| Laboratory results | |||

| White blood cell count (/mm3) | 11,290.0 (7010.0) | 13,070.0 (N/A) | 0.421 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 8.6 (2.6) | 9.8 (N/A) | 0.442 |

| Platelet count (×1000/mm3) | 259.0 (199.5) | 262.5 (N/A) | 1.000 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 101.0 (52.0) | 120.5 (N/A) | 0.971 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 40.7 (38.7) | 22.4 (N/A) | 0.213 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 2.5 (4.4) | 0.8 (N/A) | 0.073 |

| Serum total protein (g/dL) | 6.0 (1.4) | 4.8 (N/A) | 0.037 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.1 (1.1) | 3.2 (N/A) | 0.883 |

| ESR (mm/hr) | 69.0 (106.0) | 61.0 (N/A) | 0.875 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 37.7 (84.5) | 1.6 (N/A) | 0.044 |

| Reasons for considering PEX (N, (%)) | 0.326 | ||

| DAH | 5 (15.6) | 1 (50.0) | |

| RPGN | 27 (84.4) | 1 (50.0) | |

| During AAV follow-up | |||

| Poor outcomes | |||

| ACM (N, (%)) | 12 (37.5) | 1 (50.0) | 1.000 |

| Follow-up duration based on ACM (months) | 35.7 (47.3) | 29.6 (N/A) | 0.583 |

| ESKD (N, (%)) | 15 (46.9) | 0 (0) | 0.492 |

| Follow-up duration based on ESKD (months) | 12.5 (48.4) | 29.6 (N/A) | 0.942 |

| Medications administered (N, (%)) | |||

| GC | 32 (100) | 2 (100) | N/A |

| RTX | 15 (46.9) | 0 (0) | 0.492 |

| CYC | 26 (81.3) | 2 (100) | 1.000 |

| MMF | 20 (62.5) | 2 (100) | 0.529 |

| AZA | 15 (46.9) | 1 (50.0) | 1.000 |

| TAC | 3 (9.4) | 1 (50.0) | 0.225 |

| MTX | 2 (6.3) | 1 (50.0) | 0.171 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rah, W.; Kwon, O.C.; Ha, J.W.; Park, Y.-B.; Lee, S.-W. Plasma Exchange as an Adjunctive Therapeutic Option for Severe and Refractory Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-Negative Microscopic Polyangiitis and Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. Medicina 2025, 61, 2184. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122184

Rah W, Kwon OC, Ha JW, Park Y-B, Lee S-W. Plasma Exchange as an Adjunctive Therapeutic Option for Severe and Refractory Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-Negative Microscopic Polyangiitis and Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2184. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122184

Chicago/Turabian StyleRah, Woongchan, Oh Chan Kwon, Jang Woo Ha, Yong-Beom Park, and Sang-Won Lee. 2025. "Plasma Exchange as an Adjunctive Therapeutic Option for Severe and Refractory Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-Negative Microscopic Polyangiitis and Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2184. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122184

APA StyleRah, W., Kwon, O. C., Ha, J. W., Park, Y.-B., & Lee, S.-W. (2025). Plasma Exchange as an Adjunctive Therapeutic Option for Severe and Refractory Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-Negative Microscopic Polyangiitis and Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. Medicina, 61(12), 2184. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122184