Diode Laser-Guided Protocol for Endo-Perio Lesions: Toward a Multi-Stage Therapeutic Strategy—A Case Series and Brief Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

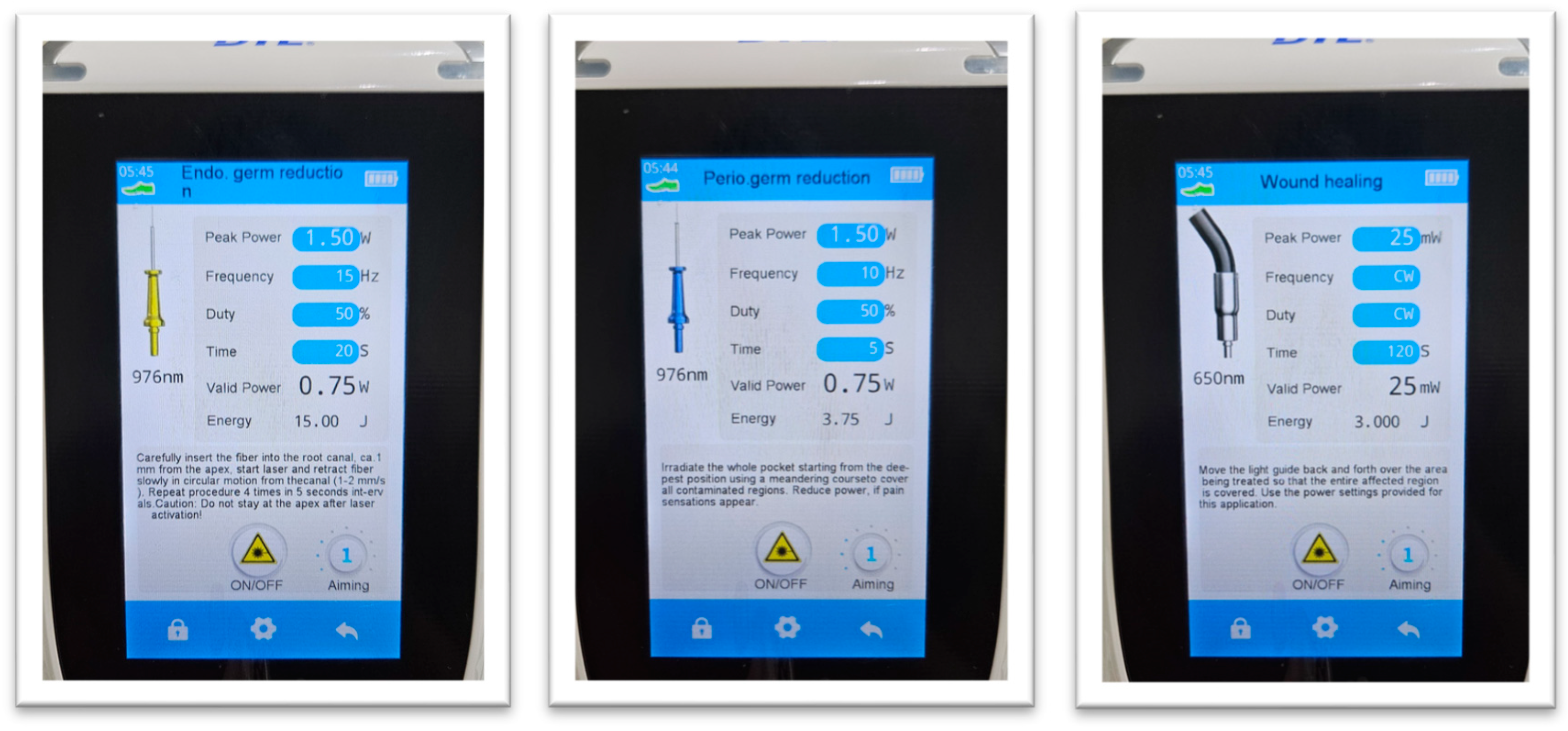

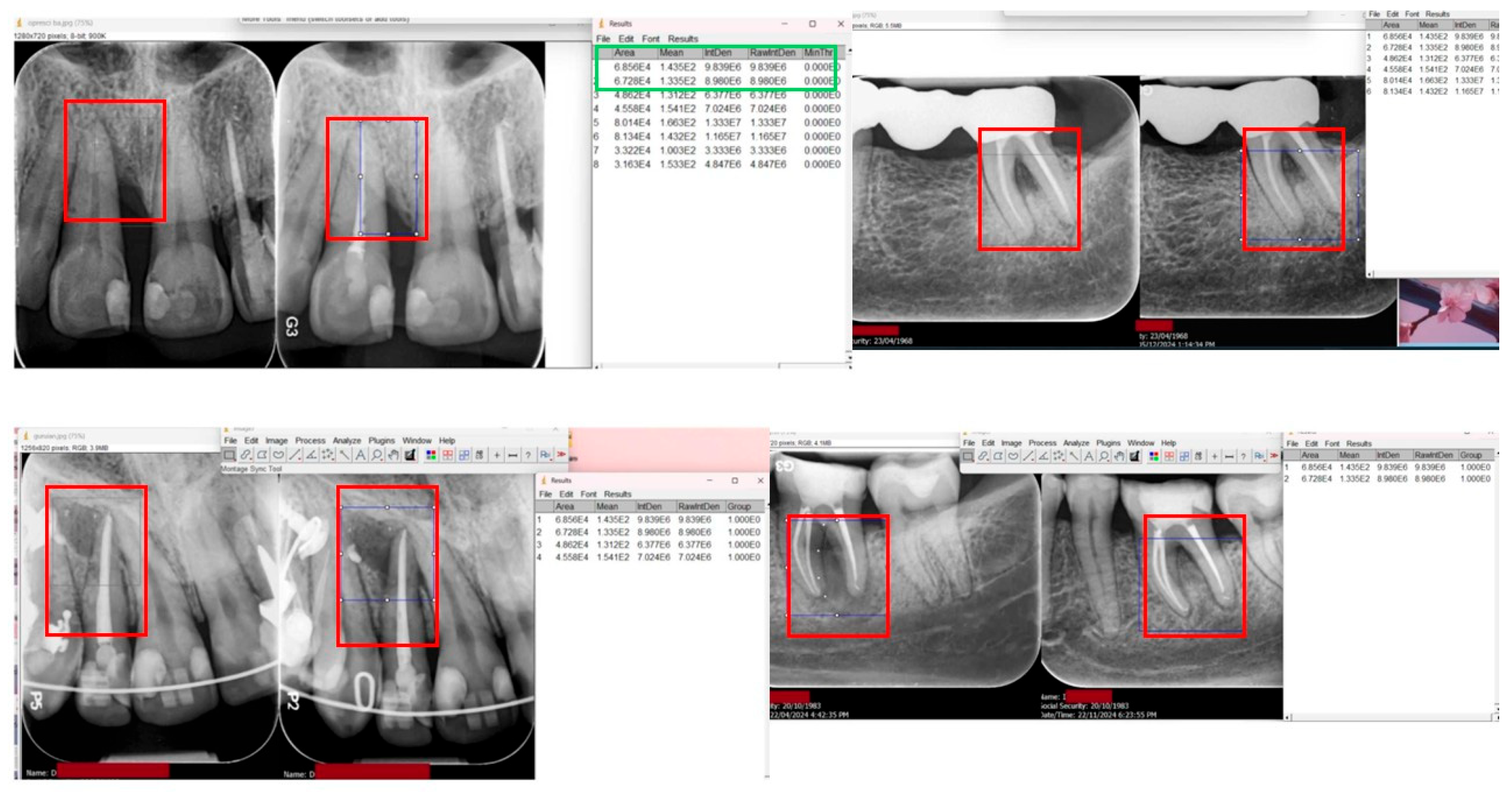

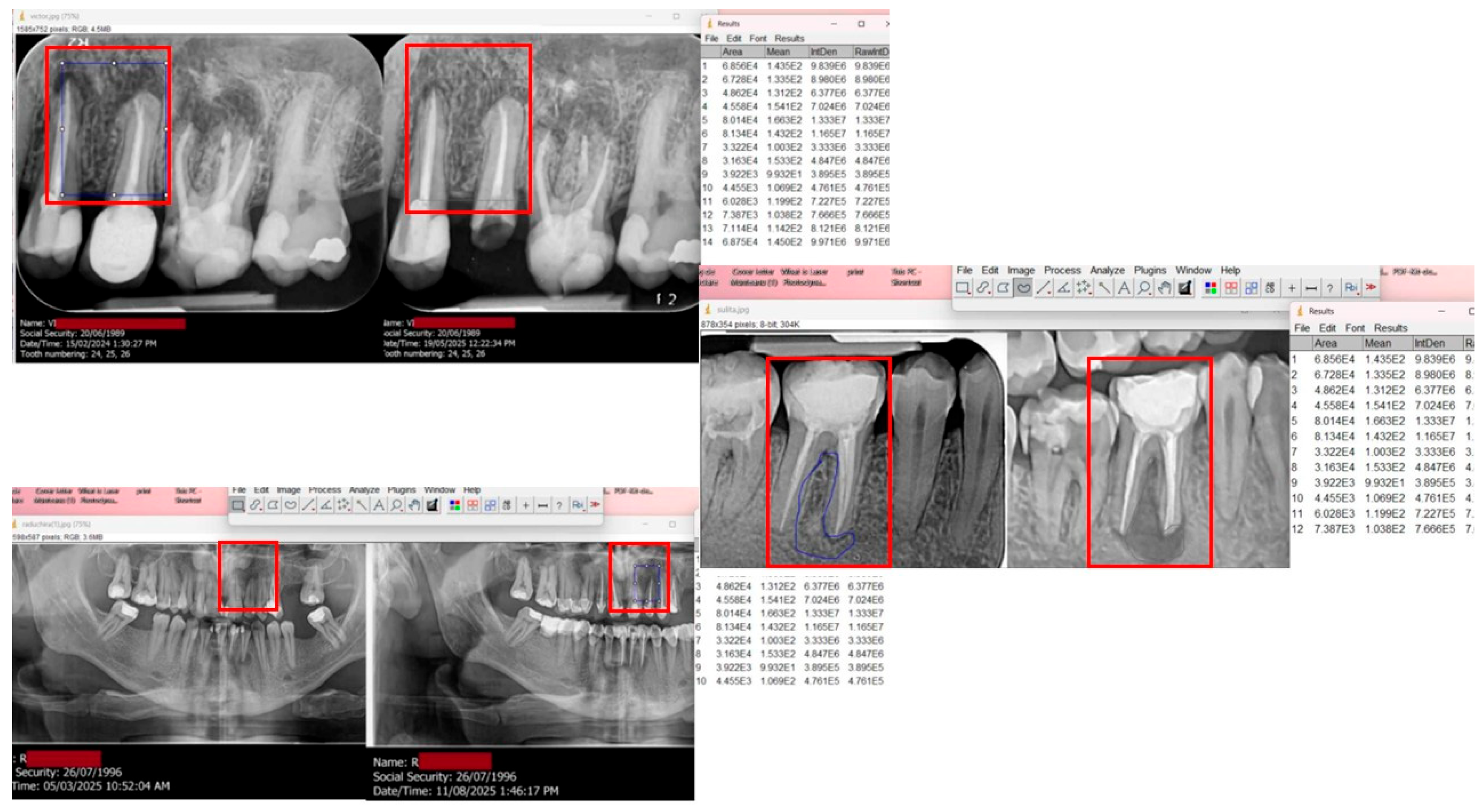

2. Materials and Methods

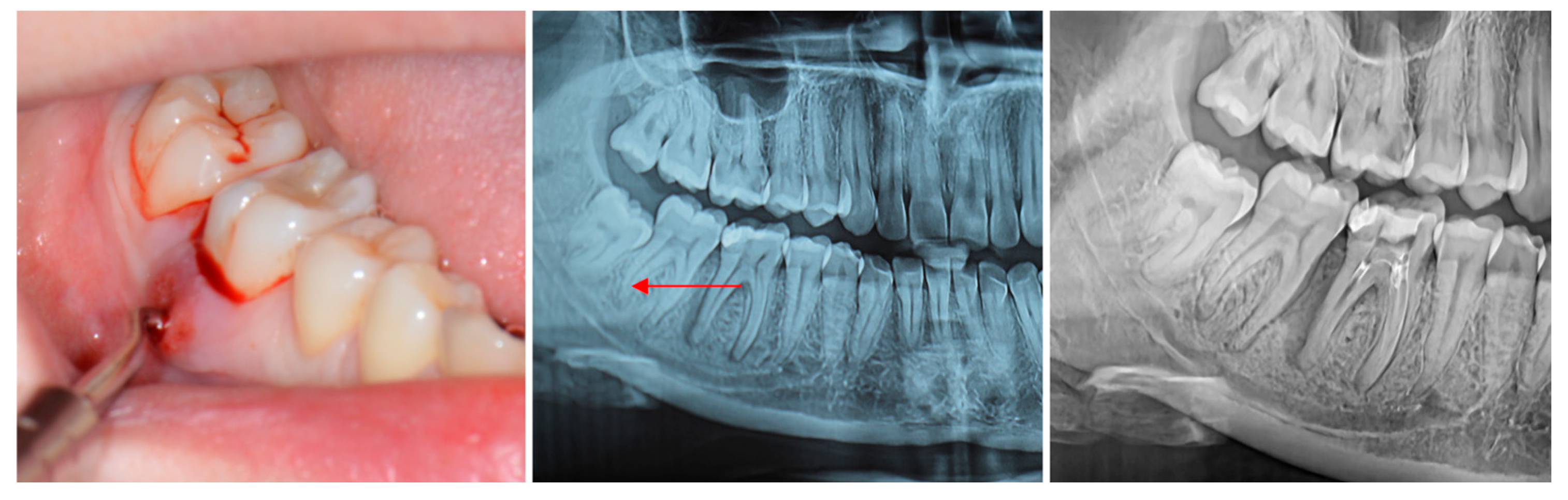

- Presence of a deep periodontal pocket (>6 mm) adjacent to a necrotic or previously treated tooth.

- Radiographic evidence of periapical and/or periodontal bone loss.

- No response to previous standard endodontic and periodontal treatments for at least three months.

- Good systemic health and willingness to comply with follow-up visits.

- Teeth with vertical root fractures, advanced mobility (Grade III), or non-restorable crowns.

- Patients with uncontrolled systemic diseases, pregnancy, smoking, or recent antibiotic or anti-inflammatory therapy.

- ○

- Probing depth (PD)

- ○

- Clinical attachment level (CAL)

- ○

- Tooth mobility (Miller’s index)

- ○

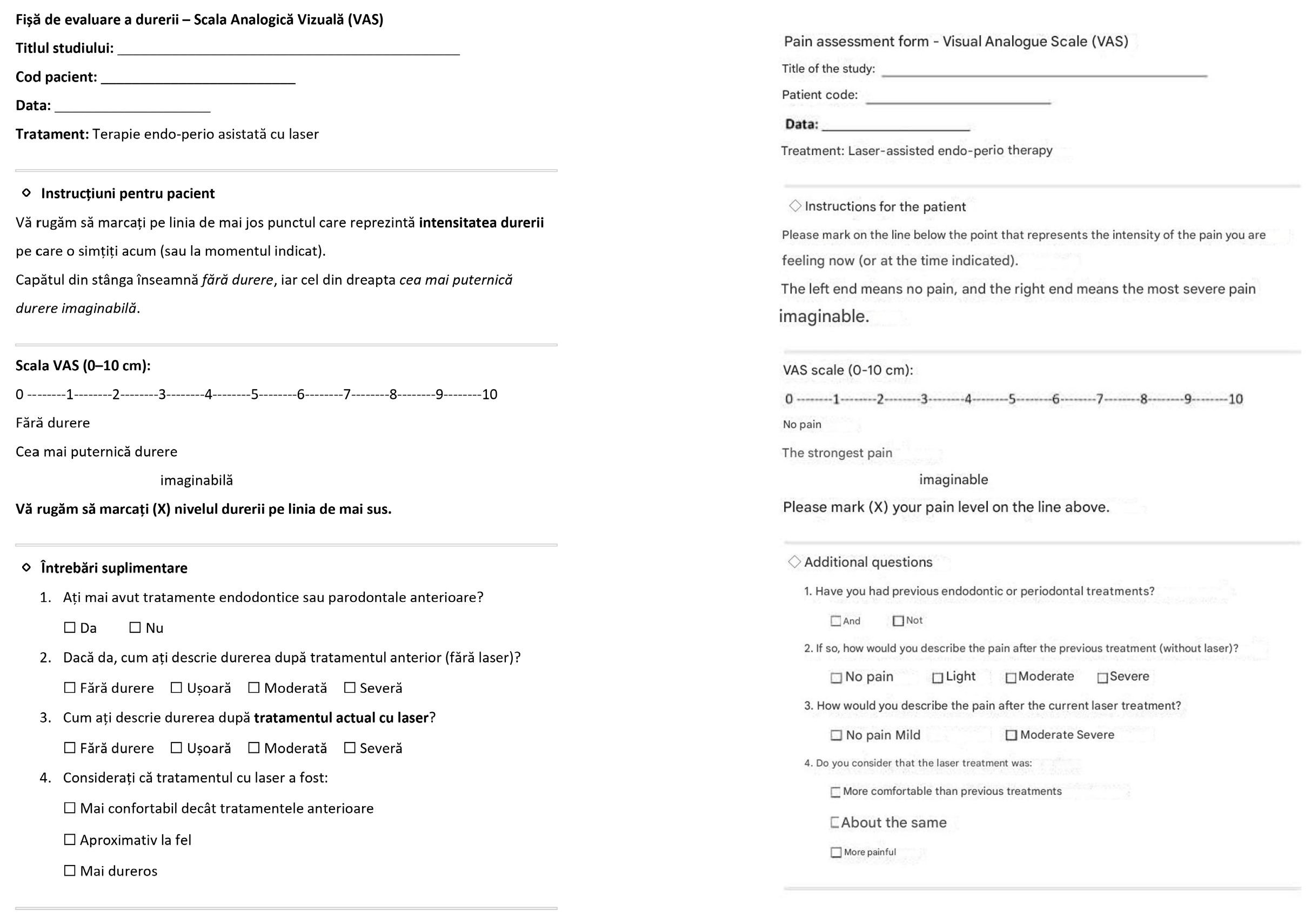

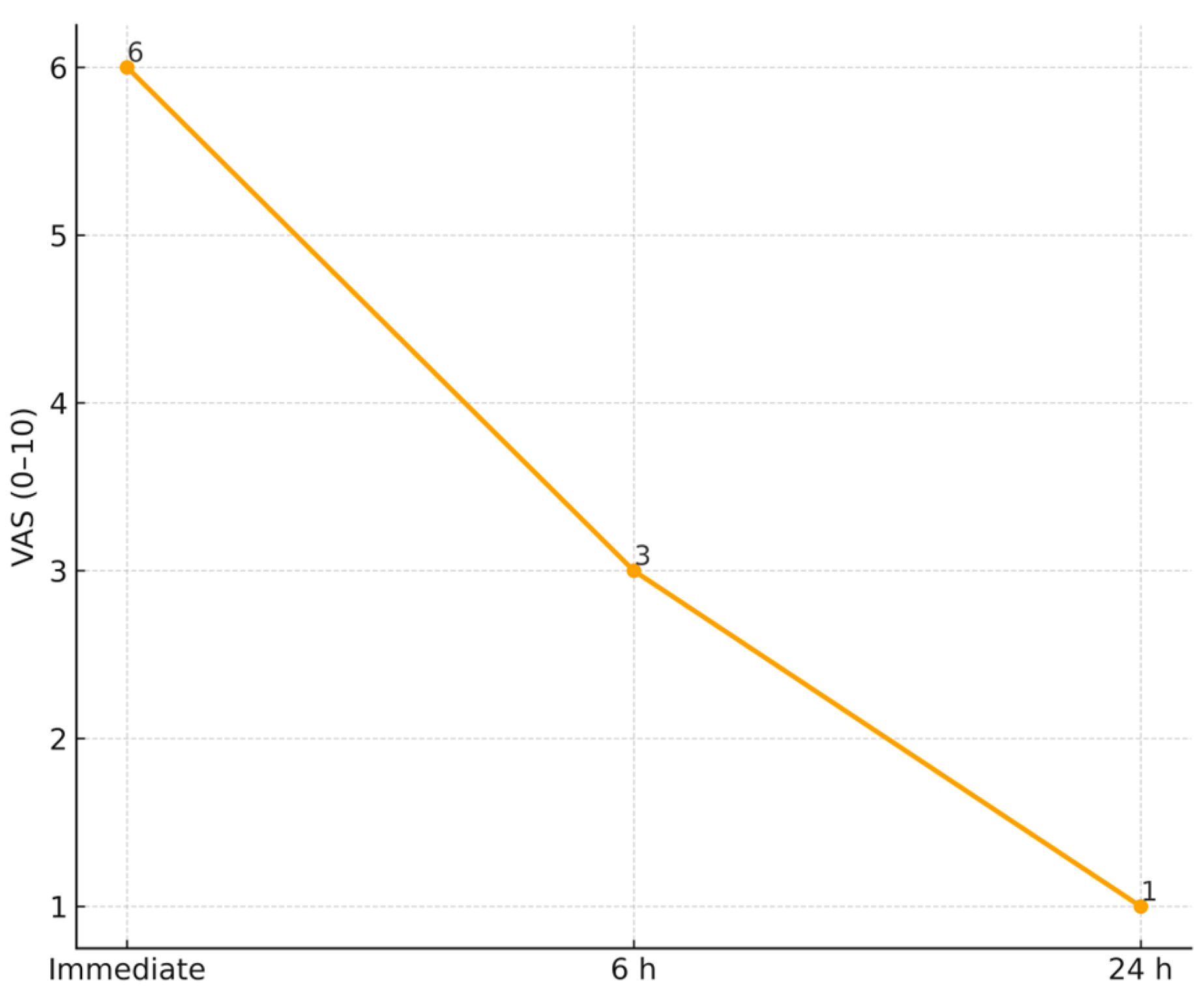

- Postoperative pain using a visual analog scale (VAS)

- ○

- Radiographic bone fill

3. Data Statistical Analysis

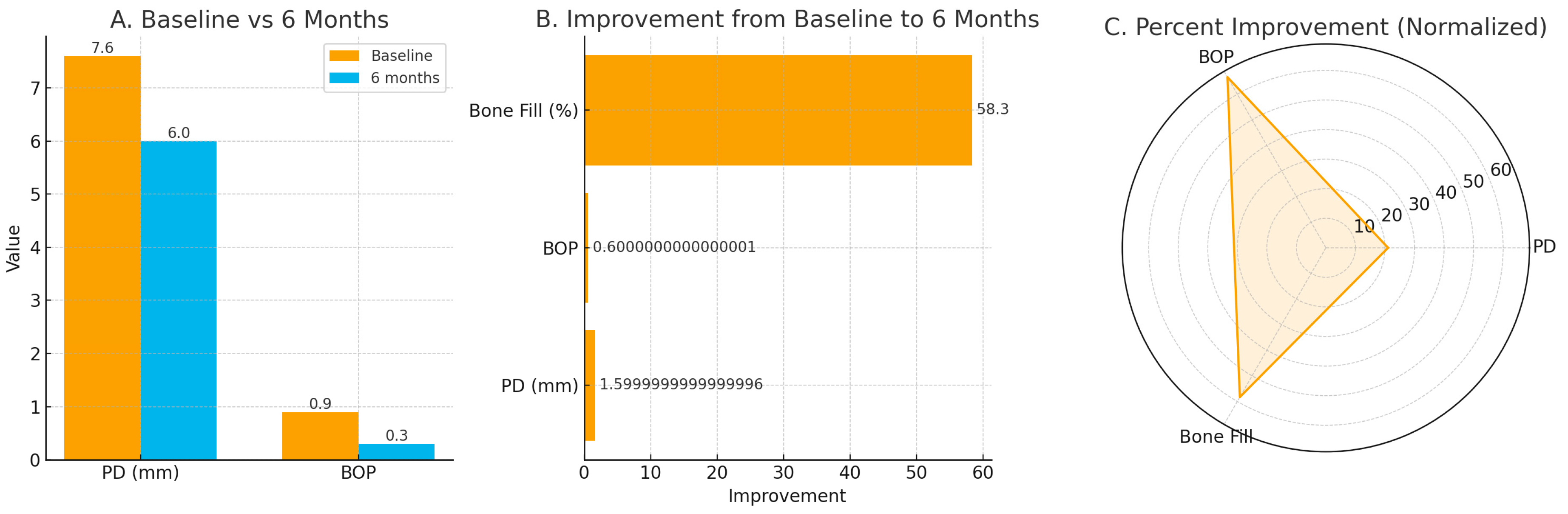

4. Results

Radiographic Evaluation

5. Discussion

6. Brief Literature Review

7. Limitations and Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| PD | Probing depth |

| CAL | Clinical attachment level |

| BOP | Bleeding on probing |

| VAS | Visual analog scale (0–10) |

| PBM | Photobiomodulation |

| LLLT | Low-level laser therapy (synonym of PBM) |

| LAI | Laser-activated irrigation |

| SRP | Scaling and root planing |

| RCT (treatment) | Root canal treatment |

| RCT (trial design) | Randomized controlled trial |

| ROI | Region of interest (for image analysis) |

| CEJ | Cemento-enamel junction |

| CBCT | Cone-beam computed tomography |

| Rx bone fill (%) | Radiographic bone fill (percentage) |

References

- Rotstein, I.; Simon, J.H. Diagnosis, prognosis and decision-making in the treatment of combined periodontal–endodontic lesions. Periodontol. 2000 2004, 34, 165–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Ouyang, X.; Ge, S.; Lin, J.; Pan, Y.; Xu, Y.; et al. Expert consensus on the diagnosis and therapy of endo-periodontal lesions. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2024, 16, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fouzan, K.S. A new classification of endodontic-periodontal lesions. Int. J. Dent. 2014, 2014, 919173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siqueira, J.F., Jr.; Rôças, I.N. Present status and future directions: Microbiology of endodontic infections. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55 (Suppl. S3), 512–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, P.N. Pathogenesis of apical periodontitis and the causes of endodontic failures. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 2004, 15, 348–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandaswamy, D.; Venkateshbabu, N. Root canal irrigants. J. Conserv. Dent. 2010, 13, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kratchman, S. Modern endodontic surgery concepts and practice: A review. J. Endod. 2006, 32, 601–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, D.; van Winkelhoff, A.J.; Matesanz, P.; Lauwens, K.; Teughels, W. Europe’s contribution to the evaluation of systemic antimicrobials in the treatment of periodontitis. Periodontol. 2000 2023, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera, D.; Matesanz, P.; Martín, C.; Oud, V.; Feres, M.; Teughels, W. Adjunctive effect of locally delivered antimicrobials in periodontitis therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47 (Suppl. S22), 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sibassi, A.; Niazi, S.; Clarke, P.; Adeyemi, A. Management of the endodontic-periodontal lesion. Br. Dent. J. 2025, 238, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricucci, D.; Siqueira, J.F. Biofilms and apical periodontitis: Study of prevalence and association with clinical and histopathologic findings. J. Endod. 2010, 36, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kishawi, M.; Khalaf, K. An update on root canal preparation techniques and how to avoid procedural errors in endodontics. Open Dent. J. 2021, 15, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.S.; Silva, J.C.; Carvalho, M.S. Hierarchical biomaterial scaffolds for periodontal tissue engineering: Recent progress and current challenges. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortellini, P.; Tonetti, M.S. Clinical concepts for regenerative therapy in intrabony defects. Periodontol. 2000 2015, 68, 282–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trentin, M.S.; Dallepiane, F.G.; Figueiredo, P.S.; Becker, A.L.; Leocovick, S.; Duque, T.M.; De Carli, J.P.; Vanni, J.R. Management of Endo-Perio Lesion in a Tooth with an Unfavorable Prognosis: A Clinical Case Report with an 18-Month Follow-Up. Odovtos 2024, 26, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheswary, T.; Nurul, A.A.; Fauzi, M.B. The insights of microbes’ roles in wound healing: A comprehensive review. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.K.; Srivastava, R.; Gupta, K.K.; Srivastava, A. Combined endodontic-periodontal lesion: A clinical dilemma. J. Interdiscip. Dent. 2011, 1, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.; Siqueira, J.F., Jr.; Lopes, W.S.P. Dentinal tubule infection as the cause of recurrent disease and late endodontic treatment failure: A case report. J. Endod. 2012, 38, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Manoil, D.; Näsman, P.; Belibasakis, G.N.; Neelakantan, P. Microbiological aspects of root canal infections and disinfection strategies: An update review. Front. Oral Health 2021, 2, 672887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keinan, D.; Nuni, E.; Bronstein Rainus, M.; Ben Simhon, T.; Dakar, A.; Slutzky-Goldberg, I.; Dakar, R. Retreatment of failed regenerative endodontic therapy: Outcome and treatment considerations. Cureus 2024, 16, e75147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavanafar, S.; Karimpour, A.; Karimpour, H.; Saleh, A.M.; Saeed, M.H. Effect of different instrumentation techniques on vertical root fracture resistance of endodontically treated teeth. J. Dent. 2015, 16 (Suppl. S1), 50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gnanadhas, D.; Elango, M.; Janardhanraj, S.; Srinandan, C.S.; Datey, A.; Strugnell, R.A.; Gopalan, J.; Chakravortty, D. Successful treatment of biofilm infections using shock waves combined with antibiotic therapy. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.R.; Rendón, J.; Ortolani-Seltenerich, P.S.; Pérez-Ron, Y.; Cardoso, M.; Noites, R.; Loroño, G.; Vieira, G.C.S. Extraradicular Infection and Apical Mineralized Biofilm: A Systematic Review of Published Case Reports. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Xie, Y.; Gao, W.; Li, C.; Ye, Q.; Li, Y. Diabetes mellitus promotes susceptibility to periodontitis—Novel insight into the molecular mechanisms. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1192625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda Verdú, S.; Pallarés Sabater, A.; Pallarés Serrano, A.; Rubio Climent, J.; Casino Alegre, A. Endo-periodontal lesions without root damage: Recommendations for clinical management. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, Y.; Shi, L.; Liu, Y.; Shen, J. New advances in periodontal functional materials based on antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and tissue regeneration strategies. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, 2403206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachelarie, L.; Cristea, R.; Burlui, E.; Hurjui, L.L. Laser technology in dentistry: From clinical applications to future innovations. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khadhim Ghafla, A.; Aalipour, R.; Khlaif, H.; Sarhan, S. The therapeutic efficacy of different power of diode laser in surgically apicectomized teeth. Nanotechnol. Percept. 2024, 20, 715–730. [Google Scholar]

- Asnaashari, M.; Sadeghian, A.; Hazrati, P. The effect of high-power lasers on root canal disinfection: A systematic review. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 13, e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutknecht, N.; Gogswaardt, D.; Conrads, G.; Apel, C.; Schubert, C.; Lampert, F. Diode laser radiation and its bactericidal effect in root canal wall dentin. J. Clin. Laser Med. Surg. 2000, 18, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzler, J.S.; Falk, W.; Frankenberger, R.; Braun, A. Impact of adjunctive laser irradiation on the bacterial load of dental root canals: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayed, Y.; Al-Haddad, A.; Kassab, A.; Alhodhodi, A.; Dar-Odeh, N.; Ragheb, Y.S.; Elbaghir, S.M.; Elsayed, S.A. From Biological Mechanisms to Clinical Applications: A Review of Photobiomodulation in Dental Practice. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2025, 43, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dembowska, E.; Jaroń, A.; Homik-Rodzińska, A.; Gabrysz-Trybek, E.; Bladowska, J.; Trybek, G. Comparison of the treatment efficacy of endo-perio lesions using a standard treatment protocol and extended by using a diode laser (940 nm). J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, T.; Sezgin, G.P.; Sönmez Kaplan, S. Effect of a 980-nm diode laser on post-operative pain after endodontic treatment in teeth with apical periodontitis: A randomized clinical trial. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, H.H.; Obeid, M.; Hassanien, E. Efficiency of diode laser in control of post-endodontic pain: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 2797–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, G.G.A.; Ferreira, G.F.; Mello, E.S.; Ando-Suguimoto, E.S.; Roncolato, V.L.; Oliveira, M.R.C.; Tognini, J.A.; Paisano, A.F.; Camacho, C.P.; Bussadori, S.K.; et al. Effect of photobiomodulation on post-endodontic pain following single-visit treatment: A randomized double-blind clinical trial. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, L.D.; da Silva, E.A.; Hespanhol, F.G.; Fontes, K.B.F.d.C.; Antunes, L.A.A.; Antunes, L.S.; Silva, E.; Antunes, L. Effect of photobiomodulation on post-operative symptoms in teeth with asymptomatic apical periodontitis treated with foraminal enlargement: A randomized clinical trial. Int. Endod. J. 2021, 54, 1708–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartols, A.; Bormann, C.; Werner, L.; Schienle, M.; Walther, W.; Dörfer, C.E. A retrospective assessment of different endodontic treatment protocols. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, O.A.; Rossi-Fedele, G.; George, R.; Kumar, K.; Timmerman, A.; Wright, P.P. Guidelines for non-surgical root canal treatment. Aust. Endod. J. 2024, 50, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S. Root canal instrumentation: Current trends and future perspectives. Cureus 2024, 16, e58045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovski, M.; Veljanovski, D.; Nikolovski, B.; Mladenovski, M.; Kovacevska, I. Contemporary aspects of treatment of endodontal–periodontal lesions. Mathews J. Dent. 2024, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, D. Scaling and root planing is recommended in the nonsurgical treatment of chronic periodontitis. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2016, 16, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plessas, A. Nonsurgical periodontal treatment: Review of the evidence. Oral Health Dent. Manag. 2014, 13, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Marcattili, D.; Mancini, L.; Tarallo, F.; Casalena, F.; Pietropaoli, C.; Marchetti, E. Efficacy of two diode lasers in the removal of calculus from the root surface: An in vitro study. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2023, 9, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.; Cronshaw, M. Laser safety in dental practice in the United Kingdom. Br. Dent. J. 2025, 238, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivanç, B.H.; Arisu, H.D.; Saglam, B.C.; Akca, G.Ü.; Gurel, M.A.; Gorgul, G. Evaluation of antimicrobial and thermal effects of diode laser on root canal dentin. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2017, 20, 1527–1530. [Google Scholar]

- Dompe, C.; Moncrieff, L.; Matys, J.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Kocherova, I.; Bryja, A.; Bruska, M.; Dominiak, M.; Mozdziak, P.; Skiba, T.H.I.; et al. Photobiomodulation—Underlying mechanism and clinical applications. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, S.; Pujar, M.; Makandar, S.; Khaiser, M. Postendodontic treatment pain management with low-level laser therapy. J. Dent. Lasers. 2014, 8, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Salceanu, M.; Melian, A.; Hamburda, T.; Antohi, C.; Concita, C.; Topoliceanu, C.; Giuroiu, C.L. Imaging techniques in endodontic diagnosis: A review of literature. Rom. J. Oral Rehabil. 2025, 17, 705–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Irfan, M.; Ali, T.; Wei, C.R.; Akilimali, A. Artificial intelligence in dental radiology: A narrative review. Ann. Med. Surg. 2025, 87, 2212–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, B.P.; Hawley, C.E.; Harrold, C.Q.; Garrett, J.S.; Polson, A.M. Reproducibility of manual periodontal probing following a comprehensive standardization and calibration training program. J. Oral Biol. 2022, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stødle, I.H.; Imber, C.; Shanbhag, S.V.; Salvi, G.E.; Verket, A.; Stähli, A. Methods for clinical assessment in periodontal diagnostics: A systematic review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2025, 52, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, G.C. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann. Periodontol. 1999, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.H.; Glick, D.H.; Frank, A.L. The relationship of endodontic-periodontic lesions. J. Periodontol. 1972, 43, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.Y.; Kim, S.; Chang, J.S.; Pyo, S.W. Advancements in methods of classification and measurement used to assess tooth mobility: A narrative review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 13, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathani, T.I.; Olivieri, J.G.; Tomás, J.; Elmsmari, F.; Abella, F.; Durán-Sindreu, F. Post-operative pain after single-visit root canal treatment using resin-based and bioceramic sealers in teeth with apical periodontitis: A randomised controlled trial. Aust. Endod. J. 2024, 50, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jundaeng, J.; Chamchong, R.; Nithikathkul, C. Advanced AI-assisted panoramic radiograph analysis for periodontal prognostication and alveolar bone loss detection. Front. Dent. Med. 2025, 5, 1509361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kui, A.; Paraschiv, A.M.; Pripon, M.; Chisnoiu, A.M.; Iacob, S.; Berar, A.; Popa, F.; Gorcea, S.; Buduru, S. From Pain to Recovery: The Impact of Laser-Assisted Therapy in Dentistry and Cranio-Facial Medicine. Balneo PRM Res. J. 2025, 16, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, S.F.; Gomaa, Y.F.; Abdelaziz, E.A.E.; Khattab, N.M.A. Influence of photobiomodulation therapy on regenerative potential of non-vital mature permanent teeth in healthy canine dogs. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2025, 26, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Asmari, D.; Alenezi, A. Laser technology in periodontal treatment: Benefits, risks, and future directions—A mini review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankowski, D.W.; Ferrucci, L.; Arany, P.R.; Bowers, D.; Eells, J.T.; Gonzalez-Lima, F.; Lohr, N.L.; Quirk, B.J.; Whelan, H.T.; Lakatta, E.G. Light buckets and laser beams: Mechanisms and applications of photobiomodulation therapy. GeroScience 2025, 47, 2777–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Lee, H.; Park, J.B. Low-level laser therapy enhances osteogenic differentiation of gingiva-derived stem cells in 2D and 3D cultures. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyed-Monir, A.; Seyed-Monir, E.; Mihandoust, S. Evaluation of 940-nm diode laser effectiveness on pocket depth, clinical attachment level, and bleeding on probing in chronic periodontitis: A randomized clinical study. Dent. Res. J. 2023, 20, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; McGrath, C.; Jin, L.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Y. The effectiveness of low-level laser therapy as an adjunct to non-surgical periodontal treatment: A meta-analysis. J. Periodontal Res. 2017, 52, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.; Cronshaw, M.; Anagnostaki, E.; Mylona, V.; Lynch, E.; Grootveld, M. Current Concepts of Laser–Oral Tissue Interaction. Dent. J. 2020, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasturk, H.; Kantarci, A. Activation and resolution of periodontal inflammation and its systemic impact. Periodontol. 2000 2015, 69, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.; Herrera, D.; Kebschull, M.; Chapple, I.; Jepsen, S.; Beglundh, T.; Sculean, A.; Tonetti, M.S.; EFP Workshop Participants and Methodological Consultants. Treatment of stage I–III periodontitis—The EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 4–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berni, M.; Brancato, A.M.; Torriani, C.; Bina, V.; Annunziata, S.; Cornella, E.; Trucchi, M.; Jannelli, E.; Mosconi, M.; Gastaldi, G.; et al. The role of low-level laser therapy in bone healing: Systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedraza, F.H.; Teves-Cordova, A.V.I.; Alcalde, M.P.; Duarte, M.A.H. Impact of the use of high-power 810-nm diode laser as monotherapy on the treatment of teeth with periapical lesions. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2025, 50, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazrati, P.; Azadi, A.; Tizno, A.; Asnaashari, M. The effect of lasers on the healing of periapical lesion: A systematic review. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2024, 15, e6. [Google Scholar]

- Amaroli, A.; Colombo, E.; Zekiy, A.; Aicardi, S.; Benedicenti, S.; De Angelis, N. Interaction between laser light and osteoblasts: Photobiomodulation as a trend in the management of socket bone preservation—A review. Biology 2020, 9, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddun, M.; Sharva, V. Laser hazards and safety in dental practice: A review. Oral Health Care 2020, 5, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshyari, N.; Mesgarani, A.; Sheikhi, M.M.; Goli, H.; Nataj, A.H.; Chiniforush, N. Comparison of antimicrobial effects of 445 and 970 nm diode laser irradiation with photodynamic therapy and triple antibiotic paste on Enterococcus faecalis in the root canal: An in vitro study. Maedica 2024, 19, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arany, P.R. Photobiomodulation Therapy. JADA Found. Sci. 2024, 4, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, M.R.; Ahrari, F.; Dokouhaki, S.; Fallahrastegar, A.; Ghasemzadeh, A. Effectiveness of an 810-nm Diode Laser in Addition to Non-surgical Periodontal Therapy in Patients with Chronic Periodontitis: A Randomized Single-Blind Clinical Trial. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2021, 12, e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Bawa, S.S.; Palwankar, P.; Kaur, S.; Choudhary, D.; Kochar, D. To Evaluate the Clinical Efficacy of 940 nm Diode Laser and Propolis Gel (A Natural Product) in Adjunct to Scaling and Root Planing in Treatment of Chronic Periodontitis. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2023, 15 (Suppl. S2), S1218–S1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Z.; Guo, Z.; Liu, Q.; Liu, N. Clinical efficacy and pain control of diode laser-assisted flap surgery in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansode, S.H.; Chole, D.G.; Bakle, S.S.; Hatte, N.R.; Gandhi, N.P.; Inamdar, M.R. In vivo evaluation of root canal disinfection using a combination of ultrasonic activation and diode laser therapy. J. Conserv. Dent. Endod. 2025, 28, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyyedi, S.A.; Fini, M.B.; Fekrazad, R.; Abbasian, S.; Abdollahi, A.A. Effect of photobiomodulation on postoperative endodontic pain: A systematic review of clinical trials. Dent. Res. J. 2024, 21, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahim, S.Z.; Ghali, R.M.; Hashem, A.A.; Farid, M.M. The efficacy of 2780 nm Er,Cr:YSGG and 940 nm Diode Laser in root canal disinfection: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galić, M.; Miletić, I.; Poklepović Peričić, T.; Rajić, V.; Jurčević, N.N.V.; Pribisalić, A.; Mikić, I.M. Antibiotic Prescribing Habits in Endodontics among Dentists in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina—A Questionnaire-Based Study. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, P.C.; Benz, L.; Nickles, K.; Petsos, H.C.; Eickholz, P.; Dannewitz, B. Decision-making on systemic antibiotics in the management of periodontitis: A retrospective comparison of two concepts. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2024, 51, 1122–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-García, M.; Hernández-Lemus, E. Periodontal inflammation and systemic diseases: An overview. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 709438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poormoradi, B.; Rabinezhad, N.; Mohamadpour, L.; Kazemi, M.; Farhadian, M. Evaluating the Effects of Diode Laser 940 nm Adjunctive to Conventional Scaling and Root Planning for Gingival Sulcus Disinfection in Chronic Periodontitis Patients. Avicenna J. Dent. Res. 2024, 16, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faragalla, A.; Awooda, E.; Bolad, A.; Ghandour, I. Efficacy of diode laser (980 nm) and non-surgical therapy on management of periodontitis: A randomized clinical trial. J. Res. Med. Dent. Sci. 2021, 9, 166–172. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, D.; Abhilash, A.; Mani, E.S.; Hari, K.; Arya, A. Clinical efficacy of locally delivered antibiotics in treating endodontic-periodontal lesions. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2025, 17 (Suppl. S2), S1767–S1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, M.; Santonocito, S.; Polizzi, A.; Tartaglia, G.M.; Ronsivalle, V.; Viglianisi, G.; Grippaudo, C.; Isola, G. Local delivery and controlled release drug systems: A new approach for the clinical treatment of periodontitis therapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiwusaer, A. Laser-assisted biofilm disruption and its role in periodontal tissue regeneration. Theor. Nat. Sci. 2025, 139, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AAE Position Statement. Guidance on the use of systemic antibiotics in endodontics. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 1409–1413. [Google Scholar]

- Munteanu, I.R.; Luca, R.E.; Mateas, M.; Darawsha, L.D.; Boia, S.; Boia, E.-R.; Todea, C.D. The Efficiency of Photodynamic Therapy in the Bacterial Decontamination of Periodontal Pockets and Its Impact on the Patient. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, I.-R.; Luca, R.-E.; Hogea, E.; Erdelyi, R.-A.; Duma, V.-F.; Marsavina, L.; Globasu, A.-L.; Constantin, G.-D.; Todea, D.C. Microbiological and Imaging-Based Evaluations of Photodynamic Therapy Combined with Er:YAG Laser Therapy in the In Vitro Decontamination of Titanium and Zirconia Surfaces. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, R.-E.; Del Vecchio, A.; Munteanu, I.-R.; Margan, M.-M.; Todea, C.D. Evaluation of the Effects of Photobiomodulation on Bone Density After Placing Dental Implants: A Pilot Study Using Cone Beam CT Analysis. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, R.E.; Giuliani, A.; Mănescu, A.; Heredea, R.; Hoinoiu, B.; Constantin, G.D.; Duma, V.-F.; Todea, C.D. Osteogenic Potential of Bovine Bone Graft in Combination with Laser Photobiomodulation: An Ex Vivo Demonstrative Study in Wistar Rats by Cross-Linked Studies Based on Synchrotron Microtomography and Histology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Baseline | 6 Months | Median Change (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probing depth (mm) | 7.6 (7.0–8.0) | 6.0 (5.5–6.5) | −1.5 (−2.0 to −1.0) |

| Bleeding on probing (proportion) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 0.3 (0.0–0.5) | −0.6 (−0.8 to −0.4) |

| Bone fill (%) | — | 58.3 (50.0–66.7) | +58.3 (50.0–66.7) |

| VAS pain score (0–10) | moderate–severe | mild at 24 h | within-patient reduction only (non-comparative) |

| Title | Year | Laser Use | Protocol (Design/Params) | Evaluation | Key Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment of stage I–III periodontitis—The EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline [68] | 2020 | Various adjunct lasers | Evidence-based CPG synthesis | PPD, CAL, BOP, patient outcomes | Insufficient evidence to recommend adjunct lasers routinely in non-surgical therapy; effects protocol-dependent. |

| Effectiveness of an 810-nm Diode Laser in Addition to Non-surgical Periodontal Therapy in Patients with Chronic Periodontitis: A Randomized Single-Blind Clinical Trial [76] | 2021 | 810 nm diode (adjunct to SRP) | RCT; SRP±diode laser; short-term follow-up | PPD, CAL, PI, BOP | Modest adjunctive gains vs SRP alone; improvements small and time-dependent. |

| Evaluation of 940-nm diode laser effectiveness on pocket depth, clinical attachment level, and bleeding on probing in chronic periodontitis: A randomized clinical study [64] | 2023 | 940 nm diode (adjunct) | Parallel RCT; SRP ± 940 nm | PPD, CAL, BOP | Adjunct benefit reported on select parameters at early follow-up; heterogeneity noted. |

| Evaluating the Effects of Diode Laser 940 nm Adjunctive to Conventional Scaling and Root Planning for Gingival Sulcus Disinfection in Chronic Periodontitis Patients [85] | 2024 | 940 nm diode (adjunct) | Split-mouth RCT; 4–8 wk | PPD, CAL, GI, BOP | Limited additional benefit overall; CAL gains at 4 & 8 wk; PD/BOP not significantly different. |

| Clinical efficacy and pain control of diode laser-assisted flap surgery in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis [78] | 2024 | Diode (810–980 nm) | Meta-analysis of RCTs | PPD (3–6 mo), pain | PPD reduction at 3 & 6 mo; analgesic benefit indicated; effect sizes vary by protocol. |

| Effect of a 980-nm diode laser on post-operative pain after endodontic treatment in teeth with apical periodontitis: A randomized clinical trial [34] | 2021 | 980 nm diode (post-RCT) | RCT; laser after chemo-mechanical prep | VAS pain at 6–48 h | Significantly lower pain at early time points vs control. |

| Efficiency of diode laser in control of post-endodontic pain: A randomized controlled trial [35] | 2023 | 810/980 nm (LLLT vs. LAI vs. manual) | 3-arm RCT (LLLT, LAI, manual) | VAS pain 24–72 h | LLLT best at 24 h; at 48 h LLLT ≈ LAI, both < manual; differences fade by 72 h. |

| Effect of photobiomodulation on postoperative endodontic pain: A systematic review of clinical trials [80] | 2024 | PBM (810–980 nm) | Systematic review of clinical trials | Post-endo pain | 7/9 studies showed significant pain reduction with PBM vs. controls. |

| The efficacy of 2780 nm Er, Cr: YSGG and 940 nm Diode Laser in root canal disinfection: A randomized clinical trial [81] | 2024 | 940 nm diode (intracanal) | Narrative/structured review | Bacterial load, disinfection | Significant bacterial reduction with laser-assisted disinfection; parameter-dependence emphasized. |

| Efficacy of diode laser (980 nm) and non-surgical therapy on management of periodontitis: A randomized clinical trial [86] | 2021 | 980 nm diode (adjunct) | Split-mouth RCT; single-dose 980 nm + SRP vs. SRP | PPD, PI, bleeding indices | Greater reductions in PPD and bleeding vs. SRP alone over 9 mo; microbiological reduction reported. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Munteanu, I.-R.; Constantin, G.-D.; Luca, R.-E.; Veja, I.; Miron, M.-I. Diode Laser-Guided Protocol for Endo-Perio Lesions: Toward a Multi-Stage Therapeutic Strategy—A Case Series and Brief Literature Review. Medicina 2025, 61, 2157. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122157

Munteanu I-R, Constantin G-D, Luca R-E, Veja I, Miron M-I. Diode Laser-Guided Protocol for Endo-Perio Lesions: Toward a Multi-Stage Therapeutic Strategy—A Case Series and Brief Literature Review. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2157. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122157

Chicago/Turabian StyleMunteanu, Ioana-Roxana, George-Dumitru Constantin, Ruxandra-Elena Luca, Ioana Veja, and Mariana-Ioana Miron. 2025. "Diode Laser-Guided Protocol for Endo-Perio Lesions: Toward a Multi-Stage Therapeutic Strategy—A Case Series and Brief Literature Review" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2157. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122157

APA StyleMunteanu, I.-R., Constantin, G.-D., Luca, R.-E., Veja, I., & Miron, M.-I. (2025). Diode Laser-Guided Protocol for Endo-Perio Lesions: Toward a Multi-Stage Therapeutic Strategy—A Case Series and Brief Literature Review. Medicina, 61(12), 2157. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122157