Endoscopic Versus Surgical Management for Infected Necrotizing Pancreatitis and Walled-Off Necrosis: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

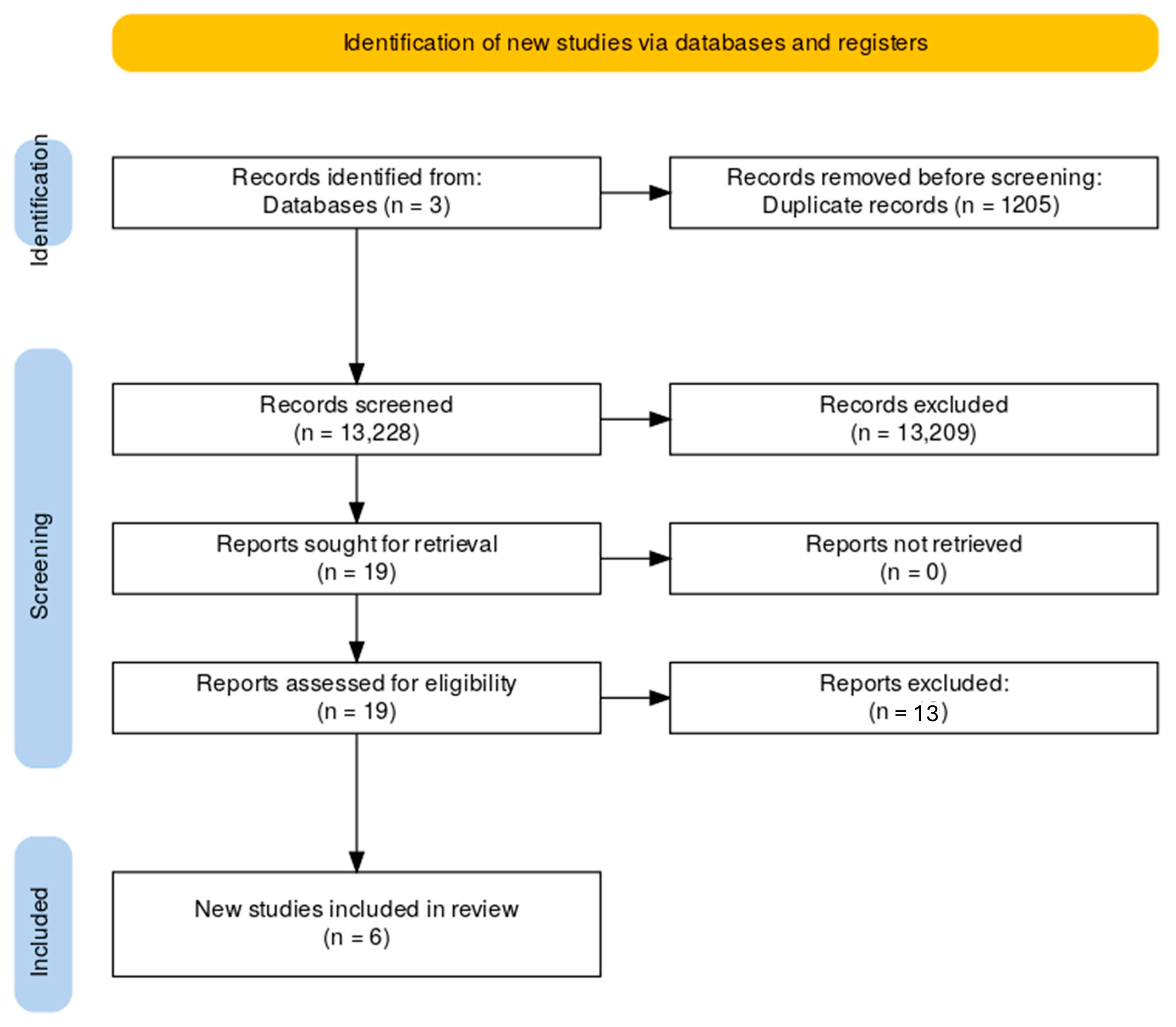

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- Population: Adults with infected necrotizing pancreatitis or symptomatic/infected walled-off necrosis

- -

- Intervention: endoscopic step-up approach (drainage ± necrosectomy)

- -

- Comparison: surgical/minimally invasive step-up approach (percutaneous drainage ± VARD/laparoscopic necrosectomy)

- -

- Outcomes: Major complications, mortality, length of stay (LOS), time to resolution of necrosis, long-term complications (endocrine or exocrine insufficiency, recurrent pancreatitis), and quality of life (QoL).

- -

- Design: Randomized controlled trials only.

“necrotizing pancreatitis OR walled-off pancreatic necrosis AND necrosectomy OR VARD OR Video-Assisted Retroperitoneal Debridement OR endoscopic drainage OR percutaneous drainage AND randomized controlled trial AND english”.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AP | Acute pancreatitis |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| D1–D5 | Domains of bias |

| EUS | Endoscopic ultrasound |

| EN | Endoscopic necrosectomy |

| EQ-5D | EuroQol-5 Dimension questionnaire |

| HbA1c | Hemoglobin A1c |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| LOS | Length of stay |

| MISN | Minimally invasive surgical necrosectomy |

| MCS | Mental Component Summary (SF-36) |

| PCS | Physical Component Summary (SF-36) |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| QALY/QALYs | Quality-adjusted life year(s) |

| RCT/RCTs | Randomized controlled trial(s) |

| RoB 2 | Revised Cochrane Risk-of-Bias Tool for Randomized Trials |

| RR | Relative risk |

| SF-36 | Short Form-36 Health Survey |

| SN | Surgical necrosectomy |

| VARD | Video-Assisted Retroperitoneal Debridement |

| WON | Walled-off necrosis |

References

- Ben-Ami Shor, D.; Ritter, E.; Borkovsky, T.; Santo, E. The Multidisciplinary Approach to Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, P.A.; Freeman, M.L. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 101, 2379–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husu, H.L.; Kuronen, J.A.; Leppäniemi, A.K.; Mentula, P.J. Open necrosectomy in acute pancreatitis–obsolete or still useful? World J. Emerg. Surg. 2020, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Santvoort, H.C.; Besselink, M.G.; Bakker, O.J.; Hofker, H.S.; Boermeester, M.A.; Dejong, C.H.; van Goor, H.; Schaapherder, A.F.; van Eijck, C.H.; Bollen, T.L.; et al. A Step-up Approach or Open Necrosectomy for Necrotizing Pancreatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1491–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollemans, R.A.; Bakker, O.J.; Boermeester, M.A.; Bollen, T.L.; Bosscha, K.; Bruno, M.J.; Buskens, E.; Dejong, C.H.; van Duijvendijk, P.; van Eijck, C.H.; et al. Superiority of Step-up Approach vs Open Necrosectomy in Long-term Follow-up of Patients With Necrotizing Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1016–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besselink, M.G.; van Santvoort, H.C.; Nieuwenhuijs, V.B.; Boermeester, M.A.; Bollen, T.L.; Buskens, E.; Dejong, C.H.; van Eijck, C.H.; van Goor, H.; Hofker, S.S.; et al. Minimally invasive “step-up approach” versus maximal necrosectomy in patients with acute necrotising pancreatitis (PANTER trial): Design and rationale of a randomised controlled multicenter trial [ISRCTN38327949]. BMC Surg. 2006, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.-W. Endoscopic transluminal drainage and necrosectomy for infected necrotizing pancreatitis: Progress and challenges. World J. Clin. Cases 2023, 11, 1888–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onnekink, A.M.; Boxhoorn, L.; Timmerhuis, H.C.; Bac, S.T.; Besselink, M.G.; Boermeester, M.A.; Bollen, T.L.; Bosscha, K.; Bouwense, S.A.W.; Bruno, M.J.; et al. Endoscopic Versus Surgical Step-Up Approach for Infected Necrotizing Pancreatitis (ExTENSION): Long-term Follow-up of a Randomized Trial. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 712–722.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorrentino, L.; Chiara, O.; Mutignani, M.; Sammartano, F.; Brioschi, P.; Cimbanassi, S. Combined totally mini-invasive approach in necrotizing pancreatitis: A case report and systematic literature review. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2017, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, O.J.; van Santvoort, H.C.; van Brunschot, S.; Geskus, R.B.; Besselink, M.G.; Bollen, T.L.; van Eijck, C.H.; Fockens, P.; Hazebroek, E.J.; Nijmeijer, R.M.; et al. Endoscopic Transgastric vs Surgical Necrosectomy for Infected Necrotizing Pancreatitis: A Randomized Trial. JAMA 2012, 307, 1053–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Brunschot, S.; van Grinsven, J.; van Santvoort, H.C.; Bakker, O.J.; Besselink, M.G.; Boermeester, M.A.; Bollen, T.L.; Bosscha, K.; Bouwense, S.A.; Bruno, M.J.; et al. Endoscopic or surgical step-up approach for infected necrotising pancreatitis: A multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, P.K.; Meena, D.; Babu, D.; Padhan, R.K.; Dhingra, R.; Krishna, A.; Kumar, S.; Misra, M.C.; Bansal, V.K. Endoscopic versus laparoscopic drainage of pseudocyst and walled-off necrosis following acute pancreatitis: A randomized trial. Surg. Endosc. 2020, 34, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar]

- Bang, J.Y.; Arnoletti, J.P.; Holt, B.A.; Sutton, B.; Hasan, M.K.; Navaneethan, U.; Feranec, N.; Wilcox, C.M.; Tharian, B.; Hawes, R.H.; et al. An Endoscopic Transluminal Approach, Compared With Minimally Invasive Surgery, Reduces Complications and Costs for Patients With Necrotizing Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1027–1040.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angadi, S.; Mahapatra, S.J.; Sethia, R.; Elhence, A.; Krishna, A.; Gunjan, D.; Prajapati, O.P.; Kumar, S.; Bansal, V.K.; Garg, P.K. Endoscopic transmural drainage tailored to quantity of necrotic debris versus laparoscopic transmural internal drainage for walled-off necrosis in acute pancreatitis: A randomized controlled trial. Pancreatology 2021, 21, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haney, C.M.; Kowalewski, K.F.; Schmidt, M.W.; Koschny, R.; Felinska, E.A.; Kalkum, E.; Probst, P.; Diener, M.K.; Müller-Stich, B.P.; Hackert, T.; et al. Endoscopic versus surgical treatment for infected necrotizing pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg. Endosc. 2020, 34, 2429–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamadnejad, M.; Anushiravani, A.; Kasaeian, A.; Sorouri, M.; Djalalinia, S.; Kazemzadeh Houjaghan, A.; Gaidhane, M.; Kahaleh, M. Endoscopic or surgical treatment for necrotizing pancreatitis: Comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc. Int. Open 2022, 10, E420–E428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.L.; Zhao, Y.; Chua, D.W.; Lim, S.J.M.; Wu, C.C.H.; Tan, D.M.Y.; Khor, C.J.L.; Goh, B.K.P.; Koh, Y.X. Comparison of treatment approaches for infected necrotizing pancreatitis: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2025, 29, 102152. Available online: https://www.jogs.org/article/S1091-255X(25)00211-2/fulltext?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 1 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, K.; Shinde, R.K.; Nagtode, T.; Jivani, A.; Goel, S.; Samuel, J.; Vaidya, K.; Shinde, D.R.K.; Nagtode, T.; Jivani, A.; et al. Role of Necrosectomy in Necrotizing Pancreatitis: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e70470. Available online: https://cureus.com/articles/301819-role-of-necrosectomy-in-necrotizing-pancreatitis-a-narrative-review (accessed on 25 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bendersky, V.A.; Mallipeddi, M.K.; Perez, A.; Pappas, T.N. Necrotizing pancreatitis: Challenges and solutions. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 2016, 9, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlek, G.; Romic, I.; Kekez, D.; Zedelj, J.; Bubalo, T.; Petrovic, I.; Deban, O.; Baotic, T.; Separovic, I.; Strajher, I.M.; et al. Step-Up versus Open Approach in the Treatment of Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis: A Case-Matched Analysis of Clinical Outcomes and Long-Term Pancreatic Sufficiency. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Ali, K.; Khizar, H.; Ni, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Xu, B.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, W. Endoscopic versus minimally invasive surgical approach for infected necrotizing pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 2276816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Cui, C.; Song, Q. Minimally invasive surgery compared to endoscopic intervention for treating infected pancreatic necrosis. A meta-analysis. Videosurgery Miniinvasive Tech. 2024, 19, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Year | Recruitment Period | Population Size * | Population | Intervention ° | Comparison ° | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakker [12] | 2012 | 2008–2010 | 34 | Infected necrotizing pancreatitis | EN = 10 | SN = 10 | Proinflammatory response and clinical outcome |

| van Brunschot S [13] | 2018 | 2011–2015 | 418 | Infected necrotizing pancreatitis | EN = 51 | SN = 47 | Major complications or death during 6-month follow-up |

| Bang JY [15] | 2019 | 2014–2017 | 168 | Infected necrotizing pancreatitis | MISN = 32 | EN = 34 | Major complications (new-onset multiple organ failure, new-onset systemic dysfunction, enteral or pancreatic-cutaneous fistula, bleeding and perforation of a visceral organ) or death during 6 months of follow-up |

| Garg PK [14] | 2020 | 2010–2015 | 182 | Symptomatic pseudocyst/WON (<30% necrotic debris of the cyst volume) | MISN = 30 | EN = 30 | Compare endoscopic and laparoscopic internal drainage of pseudocyst/walled-off necrosis following AP |

| Angadi S [16] | 2021 | 2016–2018 | 145 | WON >4 weeks duration with size >6 cm in diameter and having good interface with the stomach or duodenum, infected or symptomatic | MISN = 20 | EN = 20 | Compare laparoscopic drainage with endoscopic drainage for the resolution of WON without need of re-intervention |

| Onnekink AM [8] | 2022 | 2011–2015 | 98 | Infected necrotizing pancreatitis | EN = 51 | MISN = 47 | Mortality and major complications |

| Author | Post-Procedural Complications | |

|---|---|---|

| Bakker [12] | New-onset multiple organ failure | SN = 5 (50%) vs. EN = 0 |

| Intra-abdominal bleeding | SN = 0 vs. EN = 0 | |

| Enterocutaneous fistula | SN = 2(20%) vs. EN = 0 | |

| Pancreatic fistula | SN = 7(70%) vs. EN = 1 (10%) | |

| van Brunschot S [13] | New-onset organ failure | |

| Pulmonary | EN = 4 (8%) vs. SN = 7 (15%) RR = 0.53 (0.16–1.68); p = 0.27 | |

| Persistent pulmonary | EN = 4 (8%) vs. SN = 5 (11%) RR = 0.74 (0.21–2.58); p = 0.63 | |

| Cardiovascular | EN = 3 (6%) vs. SN = 9 (19%) RR = 0.31 (0.09–1.07); p = 0.045 | |

| Persistent cardiovascular | EN = 2 (4%) vs. SN = 8 (17%) RR = 0.23 (0.05–1.03); p = 0.032 | |

| Renal | EN = 2 (4%) vs. SN = 6 (13%) RR = 0.31 (0.07–1.45); p = 0.11 | |

| Persistent renal | EN = 2 (4%) vs. SN = 6 (13%) RR = 0.31 (0.07–1.45); p = 0.11 | |

| Single organ failure | EN = 7 (14%) vs. SN = 13 (28%) RR = 0.50 (0.22–1.14); p = 0.087 | |

| Persistent single organ failure | EN = 6 (12%) vs. SN = 11 (23%) RR = 0.50 (0.20–1.25); p = 0.13 | |

| Multiple organ failure | EN = 2 (4%) vs. SN = 6 (13%) RR = 0.31 (0.07–1.45); p = 0.11 | |

| Persistent multiple organ failure | EN = 2 (4%) vs. SN = 5 (11%) RR = 0.37 (0.08–1.81); p = 0.20 | |

| Bleeding (requiring intervention) | EN = 11 (22%) vs. SN = 10 (21%) RR = 1.01 (0.47–2.17); p = 0.97 | |

| Perforation of a visceral organ or interocutaneous fistula (requiring intervention) | EN = 4 (8%) vs. SN = 8 (17%) RR = 0.46 (0.15–1.43); p = 0.17 | |

| Pancreatic fistula | EN = 2/42 (5%) vs. SN = 13/41 (32%) RR = 0.15 (0.04–0.62); p = 0.0011 | |

| Bang JY [14] | New-onset multiple organ failure | EN = 2(5.9) vs. MISN = 3(9.4) RR = 0.63(0.11–3.51) p = 0.668 |

| New-onset multiple systemic dysfunction | EN = 0 vs. MISN = 1(3.1) p = 0.485 | |

| Enteral-pancreatic cutaneous fistula | EN = 0 vs. MISN = 9(28.1) p = 0.001 | |

| Visceral perforation | EN = 0 vs. MISN = 0 p = 0.999 | |

| Intra-abdominal bleeding | EN = 0 vs. MISN = 3(9.4) p = 0.108 | |

| Garg PK [15] | Clavien Dindo class I | |

| Delayed gastric emptying | MISN = 3 (10%) vs. EN = 1 (3.3%); p = 0.6 | |

| Surgical site infection | MISN = 5 (16.6%) | |

| Enterocutaneous fistula | MISN = 1 (3.3%) | |

| Stent migration | EN = 1 (3.3%) | |

| Clavien Dindo class II | ||

| Blood transfusion | MISN = 8 (26.6%) vs. EN = 3 (10%); p = 0.19 | |

| Fever | MISN = 9 (30.0%) vs. EN = 19 (63·3%); p = 0.01 | |

| Pneumonia | MISN = 2 (6.6%) vs. EN = 0; p = 0.5 | |

| Clavien Dindo class III | ||

| Gastric perforation with peritonitis | MISN = 0 vs. EN = 1 (3.3%); p = 0.9 | |

| Need for additional procedures | ||

| Endoscopic drainage/lavage | MISN = 3 vs. EN = 15; p = 0.0001 | |

| Percutaneous drainage | MISN = 1 vs. EN = 2 | |

| Laparoscopic drainage | EN = 2 | |

| Clavien Dindo class IVa | ||

| Respiratory failure | MISN = 1 (3.3%) vs. EN = 1 (3.3%); p = 1 | |

| Septic shock | MISN = 1 (3.3%) vs. EN = 0; p = 0.9 | |

| Peritonitis with shock | MISN = 0 vs. EN = 1 (3.3%); p = 0.9 | |

| Angadi S [16] | Clavein Dindo class I | |

| Surgical site infection | MISN = 0 | |

| Enterocutaneous fistula | MISN = 0 | |

| Stent migration | EN = 0 | |

| Clavien Dindo class II | p = 0.14 | |

| Bleeding | MISN = 1 vs. EN = 1 | |

| Secondary Infection | MISN = 5 vs. EN = 4 | |

| Clavien Dindo class III | ||

| Perforation of hollow viscus | MISN = 1 vs. EN = 0 | |

| Clavien Dindo Class IV | MISN = 0 vs. EN = 0 | |

| Onnekink AM [8] | Considering EN = 51 and MISN = 47 | |

| New-onset organ failure | EN = 11(22) vs. MISN = 15(32) RR = 0.68 (0.35–1.32); p = 0.263 | |

| Multiple new-onset organ failure | EN = 4(8) vs. MISN = 6(13) RR = 0.61 (0.19–2.04); p = 0.513 | |

| Bleeding requiring intervention | EN = 13(26) vs. MISN = 11(23) RR = 1.09 (0.54–2.19); p = 1 | |

| Perforation or enterocutaneous fistula requiring intervention | EN = 6(12) vs. MISN = 11(23) RR = 0.5(0.20–1.25); p = 0.182 | |

| Incisional hernia | EN = 4(8) vs. MISN = 4(9) RR = 0.92 (0.24–3.48); p = 1 | |

| Biliary stricture | EN = 3(6) vs. MISN = 4(9) RR = 0.69 (0.16–2.93); p = 0.707 | |

| Wound infection | EN = 3(6) vs. MISN = 4(9) RR = 0.69 (0.16–2.93); p = 0.707 | |

| Pancreatic fistula | EN = 4(8) vs. MISN = 16(34) RR = 0.23 (0.08–0.64); p = 0.002 |

| Author | Mortality | LOS (Days) | Long-Term Complications | QoL After Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakker [12] | SN = 4 (40%) EN = 1 (10%) | SN = 36 (17–74) EN = 45 (12–69) | New-onset diabetes SN = 3 (50%) vs. EN = 2 (22%) Use of pancreatic enzymes SN = 3 (50%) EN = 0 Persisting fluid collection SN = 3 (50%) vs. EN = 2 (22%) | - |

| van Brunschot S [13] | EN = 9 (18%) SN = 6 (13%) | EN = 35 (19–85) SN = 65 (40–90) | Exocrine insufficiency Use of enzymes EN = 16/42 (38%) vs. SN = 13/41 (32%) RR = 1.20 (0.66–2.17); p = 0.54 Fecal elastase <200 mg/g EN = 22/42 (52%) vs. SN = 19/41 (46%) RR = 1.13 (0.73–1.75); p = 0.58 Steatorrhea EN = 6/42 (14%) vs. SN = 7/41 (17%) RR = 0.84 (0.31–2.28); p = 0.73 Endocrine insufficiency EN = 10/42 (24%) vs. SN = 9/41 (22%) RR = 1.08 (0.49–2.39); p = 0.84 | QALYs EN = 0.2788 (0.2458–0.3110) vs. SN = 0.2988 (0.2524–03398) Mean difference = −0.0199 (−0.0732–0.0395) |

| Bang JY [15] | EN = 3 (8.8) MISN = 2 (6.3) RR = 1.41 (0.25–7.91); p = 0.999 | Median (IQR) EN = 14 (6–22) MISN = 18.5 (11.5–29.5) | New onset diabetes EN = 6 (27.3) vs. SD = 9 (36.0) RR = 0.76 (0.32–1.79); p = 0.522 New diagnosis of pancreatic insufficiency EN = 29 (85.3) vs. MISN = 28 (87.5) RR = 0.97 (0.80–1.18); p = 0.999 | Quality of life at 3-month follow-up EN = MCS: 0.22 (9.18–8.87) p = 0.962 EN = PCS: 5.29 (0.27–10.3) p = 0.039 |

| Garg PK [14] | EN = 0 vs. MISN = 0 | MISN = 7 (4–52) EN = 8 (3–69) p = 0.1 | - | - |

| Angadi S [16] | MISN = 0 vs. EN = 0 | MISN = 6 (5–9) EN = 4 (4–8) p = 0.037 | - | - |

| Onnekink AM [8] | 15 of 51 patients (29%) in the endoscopy group and 7 of 47 patients (15%) in the surgery group died (RR, 1.89; 95% CI, 0.89–4.42). p-value 0.616 | Median (IQR) EN = 52 (27–94) MISN = 72 (50–112) p = 0.090 | Comparing EN = 36 vs. MISN = 40 Endocrine pancreatic insufficiency (HbA1c) EN = 16 (44) vs. MISN = 16 (40) RR = 1.11 (0.66–1.88); p = 0.817 Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency FE-1 < 200 mg/g EN = 12/27 (44) vs. MISN = 12/30 (40) RR = 1.11 (0.61–2.04); p = 0.792 Enzyme use at long-term follow-up EN = 11/36 (31) vs. MISN = 12/40 (30) RR = 1.02 (0.51–2.02); p = 0.792 | Comparing EN = 29 vs. MISN = 30 SF-36 PCS EN = 45 ± 11 vs. MISN = 47 ± 10 p = 0.475 MCS EN = 48 ± 12 vs. MISN = 52 ± 10 p = 0.152 EQ-5D EN = 0.80 ± 0.23 vs. MISN = 0.86 ± 0.17 p = 0.237 Health state score EN = 72 ± 18 vs. MISN = 77 ± 13 p = 0.263 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mastronardi, M.; Moghnie, G.; Crociato, S.; Menghini, C.; Giordano, A.B.F.; Germani, P.; Sandano, M.; de Manzini, N.; Biloslavo, A. Endoscopic Versus Surgical Management for Infected Necrotizing Pancreatitis and Walled-Off Necrosis: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Medicina 2025, 61, 2149. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122149

Mastronardi M, Moghnie G, Crociato S, Menghini C, Giordano ABF, Germani P, Sandano M, de Manzini N, Biloslavo A. Endoscopic Versus Surgical Management for Infected Necrotizing Pancreatitis and Walled-Off Necrosis: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2149. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122149

Chicago/Turabian StyleMastronardi, Manuela, Giada Moghnie, Sara Crociato, Chiara Menghini, Alessio Biagio Filippo Giordano, Paola Germani, Margherita Sandano, Nicolò de Manzini, and Alan Biloslavo. 2025. "Endoscopic Versus Surgical Management for Infected Necrotizing Pancreatitis and Walled-Off Necrosis: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2149. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122149

APA StyleMastronardi, M., Moghnie, G., Crociato, S., Menghini, C., Giordano, A. B. F., Germani, P., Sandano, M., de Manzini, N., & Biloslavo, A. (2025). Endoscopic Versus Surgical Management for Infected Necrotizing Pancreatitis and Walled-Off Necrosis: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Medicina, 61(12), 2149. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122149