Correction: Poštuvan et al. A Lonelier World after COVID-19: Longitudinal Population-Based Study of Well-Being, Emotional and Social Loneliness, and Suicidal Behaviour in Slovenia. Medicina 2024, 60, 312

| Wave 0 | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–24 [N (%)] | 19 (4.28) | 8 (1.80) | 6 (1.35) | 2 (0.45) |

| 25–64 [N (%)] | 337 (75.90) | 317 (71.40) | 311 (70.05) | 311 (70.05) | |

| 65–79 [N (%)] | 87 (19.60) | 112 (25.22) | 114 (25.67) | 117 (26.35) | |

| >80 [N (%)] | 1 (0.22) | 7 (1.58) | 13 (2.93) | 14 (3.15) |

| Measures | Wave 0 | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

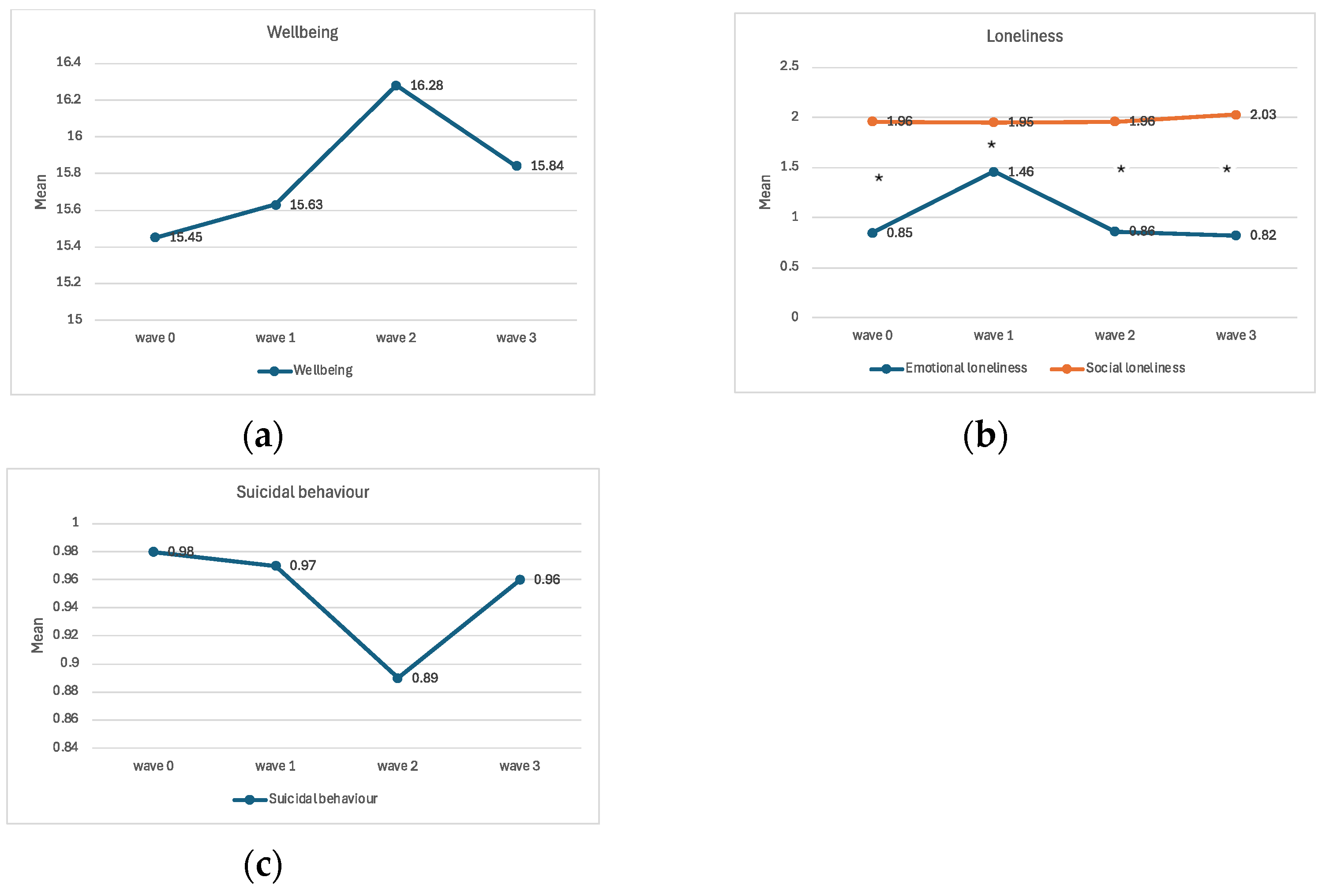

| Well-being | All [M ± SD] | 15.45 ± 4.67 | 15.63 ± 5.31 | 16.28 ± 4.92 | 15.84 ± 5.11 |

| Female [M ± SD] | 14.80 ± 4.80 | 14.73 ± 5.39 | 15.25 ± 5.16 | 14.94 ± 5.43 | |

| Male [M ± SD] | 16.04 ± 4.48 | 16.45 ± 5.12 | 17.21 ± 4.51 | 16.67 ± 4.66 | |

| Social Loneliness | All [M ± SD] | 1.99 ± 1.18 | 1.95 ± 1.25 | 1.96 ± 1.23 | 2.03 ± 1.22 |

| Female [M ± SD] | 1.82 ± 1.25 | 1.85 ± 1.28 | 1.88 ± 1.27 | 1.89 ± 1.28 | |

| Male [M ± SD] | 2.14 ± 1.08 | 2.03 ± 1.21 | 2.03 ± 1.20 | 2.16 ± 1.16 | |

| Emotional Loneliness | All [M ± SD] | 0.85 ± 1.05 | 1.46 ± 0.95 | 0.86 ± 1.05 | 0.82 ± 1.09 |

| Female [M ± SD] | 0.82 ± 1.05 | 1.52 ± 0.92 | 0.91 ± 1.09 | 0.89 ± 1.13 | |

| Male [M ± SD] | 0.89 ± 1.06 | 1.40 ± 0.97 | 0.81 ± 1.00 | 0.76 ± 1.05 | |

| Suicidal Behaviour | All [M ± SD] | 0.98 ± 2.24 | 0.97 ± 2.46 | 0.89 ± 2.28 | 0.96 ± 2.34 |

| Female [M ± SD] | 1.13 ± 2.52 | 1.18 ± 2.70 | 0.94 ± 2.30 | 0.99 ± 2.26 | |

| Male [M ± SD] | 0.84 ± 1.96 | 0.79 ± 2.21 | 0.84 ± 2.26 | 0.94 ± 2.41 |

| Measures | Wave 0 | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-being | All [M ± SD] | 15.45 ± 4.67 | 15.63 ± 5.31 | 16.28 ± 4.92 | 15.84 ± 5.11 |

| 18–24 [M ± SD] | 14.95 ± 4.39 | 12.88 ± 4.85 | 14.83 ± 3.19 | 16.0 ± 1.41 | |

| 25–64 [M ± SD] | 15.05 ± 4.81 | 15.37 ± 5.28 | 15.97 ± 4.98 | 15.39 ± 5.26 | |

| 65–79 [M ± SD] | 17.06 ± 3.78 | 16.70 ± 5.20 | 17.04 ± 4.71 | 16.97 ± 4.59 | |

| >80 [M ± SD] | / | 13.71 ± 6.87 | 17.54 ± 5.62 | 16.50 ± 4.97 | |

| Social Loneliness | All [M ± SD] | 1.99 ± 1.18 | 1.95 ± 1.25 | 1.96 ± 1.23 | 2.03 ± 1.22 |

| 18–24 [M ± SD] | 1.95 ± 1.31 | 2.25 ± 1.17 | 2.67 ± 0.52 | 3.00 ± 0.00 | |

| 25–64 [M ± SD] | 2.04 ± 1.14 | 1.97 ± 1.23 | 1.96 ± 1.23 | 2.06 ± 1.22 | |

| 65–79 [M ± SD] | 1.82 ± 1.27 | 1.87 ± 1.28 | 1.92 ± 1.27 | 2.02 ± 1.23 | |

| >80 [M ± SD] | / | 1.86 ± 1.46 | 1.92 ± 1.26 | 1.43 ± 1.28 | |

| Emotional Loneliness | All [M ± SD] | 0.85 ± 1.05 | 1.46 ± 0.95 | 0.86 ± 1.05 | 0.82 ± 1.09 |

| 18–24 [M ± SD] | 1.32 ± 1.20 | 1.75 ± 1.16 | 1.17 ± 1.33 | 1.00 ± 1.41 | |

| 25–64 [M ± SD] | 0.86 ± 1.06 | 1.38 ± 0.96 | 0.85 ± 1.06 | 0.86 ± 1.13 | |

| 65–79 [M ± SD] | 0.75 ± 0.99 | 1.59 ± 0.89 | 0.81 ± 0.99 | 0.72 ± 1.02 | |

| >80 [M ± SD] | / | 2.43 ± 0.79 | 1.38 ± 1.12 | 0.86 ± 1.10 | |

| Suicidal Behaviour | All [M ± SD] | 0.98 ± 2.25 | 0.97 ± 2.46 | 0.89 ± 2.28 | 0.96 ± 2.34 |

| 18–24 [M ± SD] | 1.68 ± 3.53 | 0.75 ± 0.89 | 1.33 ± 2.34 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| 25–64 [M ± SD] | 0.97 ± 2.24 | 1.05 ± 2.63 | 0.93 ± 2.24 | 1.05 ± 2.48 | |

| 65–79 [M ± SD] | 0.86 ± 1.88 | 0.63 ± 1.53 | 0.54 ± 1.36 | 0.62 ± 1.43 | |

| >80 [M ± SD] | / | 3.14 ± 5.43 | 2.69 ± 6.07 | 1.93 ± 4.36 |

| Measures | F | df | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-being | 5.71 | 2.87 | <0.01 | 0.01 |

| Social loneliness | 0.81 | 3 | 0.49 | <0.01 |

| Emotional loneliness | 72.64 | 2.88 | <0.01 | 0.14 |

| Suicidal behaviour | 0.27 | 2.77 | 0.83 | <0.01 |

| Measures | Comparisons | F | df | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-being | Wave 0 vs. Wave 1 | 0.61 | 1 | 0.44 | <0.01 |

| Wave 1 vs. Wave 2 | 10.08 | 1 | <0.01 | 0.02 | |

| Wave 2 vs. Wave 3 | 5.70 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.01 | |

| Social loneliness | Wave 0 vs. Wave 1 | 0.44 | 1 | 0.51 | <0.01 |

| Wave 1 vs. Wave 2 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.82 | <0.01 | |

| Wave 2 vs. Wave 3 | 1.51 | 1 | 0.22 | <0.01 | |

| Emotional loneliness | Wave 0 vs. Wave 1 | 125.13 | 1 | <0.01 | 0.22 |

| Wave 1 vs. Wave 2 | 160.40 | 1 | <0.01 | 0.27 | |

| Wave 2 vs. Wave 3 | 0.71 | 1 | 0.40 | <0.01 | |

| Suicidal behaviour | Wave 0 vs. Wave 1 | <0.01 | 1 | 0.97 | <0.01 |

| Wave 1 vs. Wave 2 | 0.67 | 1 | 0.41 | <0.01 | |

| Wave 2 vs. Wave 3 | 0.58 | 1 | 0.45 | <0.01 |

- Abstract:

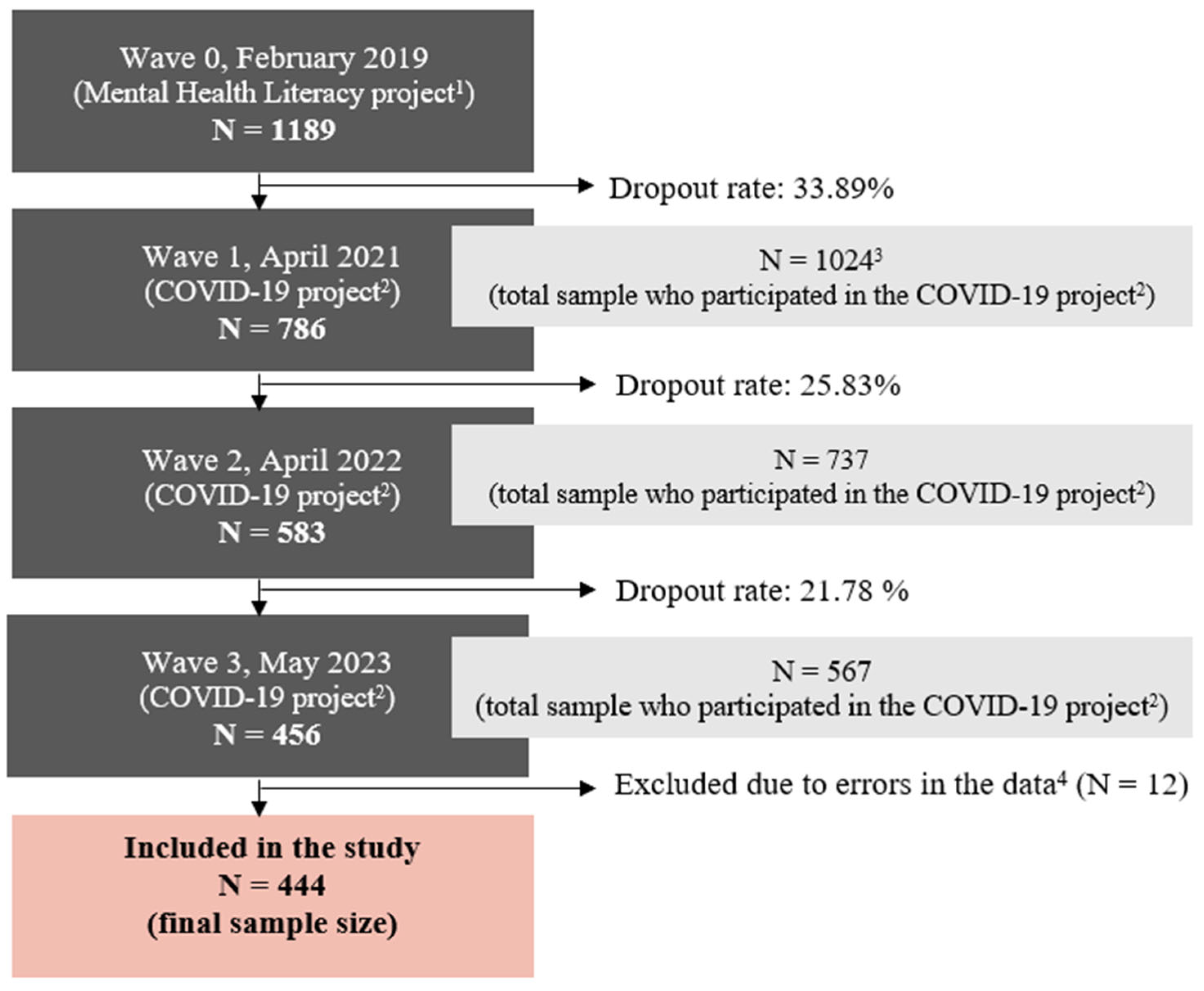

- 2.2. Participants

- 2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Reference

- Poštuvan, V.; Krohne, N.; Lavrič, M.; Gomboc, V.; De Leo, D.; Rojs, L. A Lonelier World after COVID-19: Longitudinal Population-Based Study of Well-Being, Emotional and Social Loneliness, and Suicidal Behaviour in Slovenia. Medicina 2024, 60, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poštuvan, V.; Krohne, N.; Lavrič, M.; Gomboc, V.; De Leo, D.; Rojs, L. Correction: Poštuvan et al. A Lonelier World after COVID-19: Longitudinal Population-Based Study of Well-Being, Emotional and Social Loneliness, and Suicidal Behaviour in Slovenia. Medicina 2024, 60, 312. Medicina 2025, 61, 1867. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61101867

Poštuvan V, Krohne N, Lavrič M, Gomboc V, De Leo D, Rojs L. Correction: Poštuvan et al. A Lonelier World after COVID-19: Longitudinal Population-Based Study of Well-Being, Emotional and Social Loneliness, and Suicidal Behaviour in Slovenia. Medicina 2024, 60, 312. Medicina. 2025; 61(10):1867. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61101867

Chicago/Turabian StylePoštuvan, Vita, Nina Krohne, Meta Lavrič, Vanja Gomboc, Diego De Leo, and Lucia Rojs. 2025. "Correction: Poštuvan et al. A Lonelier World after COVID-19: Longitudinal Population-Based Study of Well-Being, Emotional and Social Loneliness, and Suicidal Behaviour in Slovenia. Medicina 2024, 60, 312" Medicina 61, no. 10: 1867. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61101867

APA StylePoštuvan, V., Krohne, N., Lavrič, M., Gomboc, V., De Leo, D., & Rojs, L. (2025). Correction: Poštuvan et al. A Lonelier World after COVID-19: Longitudinal Population-Based Study of Well-Being, Emotional and Social Loneliness, and Suicidal Behaviour in Slovenia. Medicina 2024, 60, 312. Medicina, 61(10), 1867. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61101867