3. Results

Among the participants, 363 were women (79.08%) and 96 were men (20.92%). Age ranged from 18 to over 80 years, with a mean of 33.3 years and a median of 24.5 years (

Figure 1).

The age distribution was asymmetric, showing a clear predominance of younger individuals. More than half of the sample (52.1%) fell within the 20–29 age range, followed by 22.4% in the 30–39 group and 11.3% in the 40–49 group. Only a small proportion of participants (approximately 12%) were aged 50 years or older.

The total scores exhibited a slightly asymmetric distribution (skewness = 0.67) and a slight leptokurtosis (kurtosis = 0.74), indicating a concentration of values around the mean and a moderate reduction in extreme values. This trend suggests a moderate prevalence of oral behaviors in the analyzed population, with a moderate dispersion around the mean score (

Table 1).

The mean OBC score was 22.45 (SD = 10.27, Median = 21). Based on the established cutoff values, 276 participants (60.13%) were classified as low risk and 183 (39.87%) as high risk, while none of the participants fell into the no-risk category.

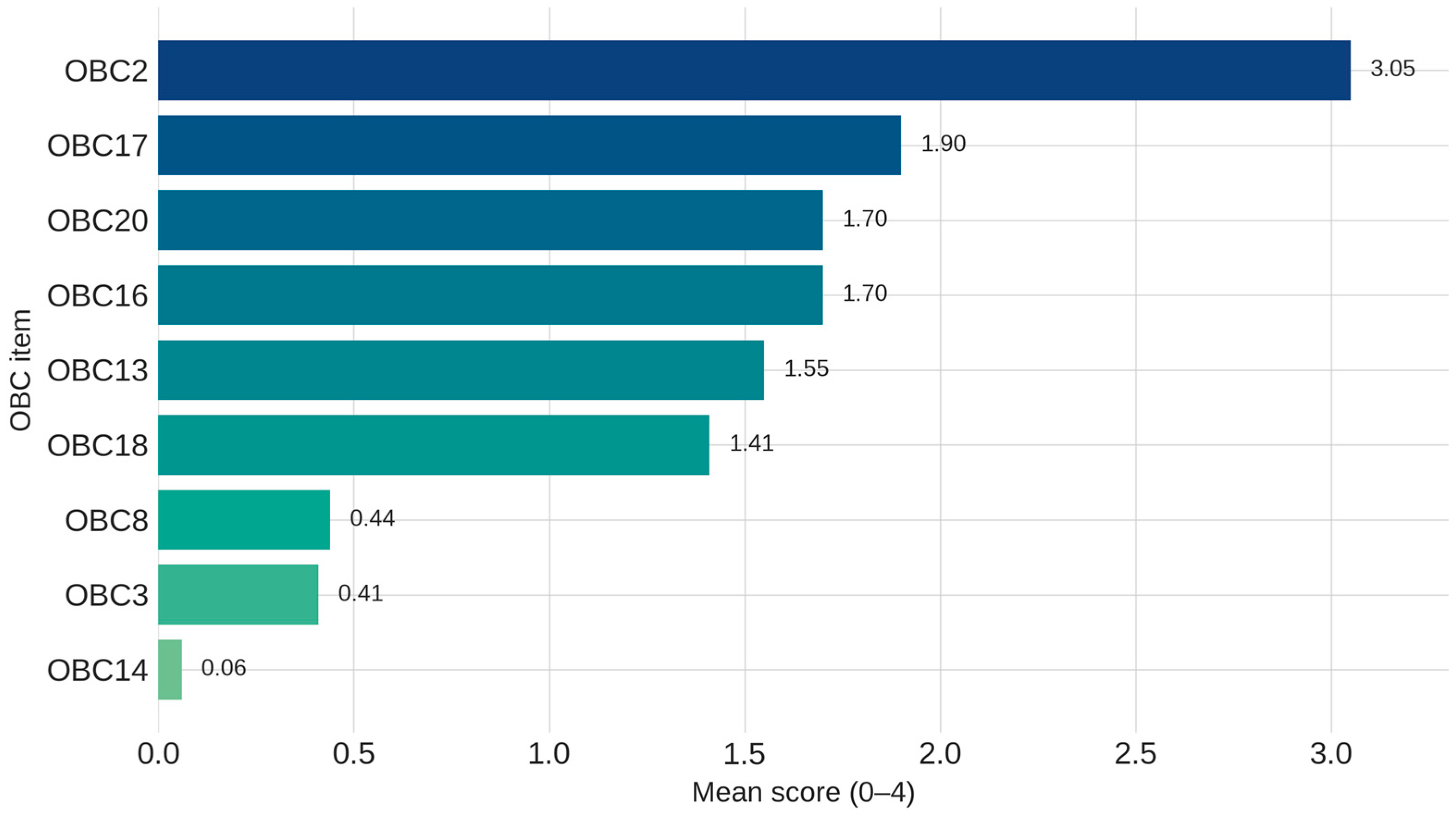

The mean values of the individual items ranged from 0.06 to 3.05, while the standard deviation varied between 0.80 and 1.39, indicating a moderate dispersion of scores and considerable variability in the frequency with which these behaviors were reported (

Figure 1). Detailed descriptive statistics for individual items, as well as the total score, are presented in

Supplementary Table S1.

The analysis of individual OBC-21 items revealed substantial variability in the frequency and intensity of reported oral behaviors.

The most frequently reported behaviors were:

OBC2—“Sleep in a position that puts pressure on the jaw” (Mean = 3.05);

OBC17—“Eating between meals” (Mean = 1.90);

OBC20—“Yawning” (Mean = 1.70);

OBC16—“Chewing food on one side only” (Mean = 1.70);

OBC13—“Use chewing gum” (Mean = 1.55);

OBC18—“Sustained talking” (Mean = 1.41).

In contrast, the items with the lowest mean scores included:

OBC14—“Playing musical instrument that involves use of mouth or jaw” (Mean = 0.06);

OBC3—“Grinding teeth together during waking hours” (Mean = 0.41);

OBC8—“Press tongue forcibly against teeth” (Mean = 0.44).

These low mean scores indicate a limited prevalence of such behaviors in the study population.

Participants’ responses were assessed using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). The distribution of response frequencies for each OBC-21 item revealed marked inter-item variability, reflecting differences in the expression of oral behaviors across the sample. The complete distribution of response frequencies for all items is presented in

Supplementary Table S2.

The behaviors most frequently reported at the maximum frequency level (score 4–very often) included sleeping in a position that puts pressure on the jaw (OBC2), endorsed by 57.7% of participants. This was followed by sustained talking (OBC18), reported by 11.3% of participants, and nocturnal bruxism (OBC1), reported by 10.5%.

Among behaviors reported with high frequency (score 3–often), the highest proportions were observed for eating between meals (OBC17; 19.8%), chewing food on one side only (OBC16; 19.2%), and again sleeping in a position that puts pressure on the jaw (OBC2; 17.4%).

In contrast, several behaviors were rarely reported. For example, playing a musical instrument involves use of the mouth or jaw (OBC14) was reported as very often by only 0.2% of participants and as often by 0.4%. Grinding teeth together during waking hours (OBC3) was reported by 0.9% of participants for score 4 and 1.7% for score 3. Other infrequent behaviors, including hold or jut jaw forward or to the side (OBC7), holding jaw in rigid or tense position, such as to brace or protect it (OBC11), and holding, tighten, or tense muscles without clenching or bringing teeth together (OBC6), showed similarly low endorsement rates for the higher frequency categories.

The comparison of OBC total scores across age categories initially suggested a statistically significant association (χ

2 = 536.33,

p < 0.001) (

Table 2). However, because 94.8% of the expected cell counts were below five, the assumptions for the Pearson Chi-square test were not met. In accordance with standard statistical practice, the Likelihood Ratio test was therefore applied, and the results did not confirm a significant association between age group and OBC scores (

p = 0.987).

Descriptive examination of the score distribution indicated that moderate-to-high OBC scores (20–35) were more frequently observed among participants aged 20–49 years, whereas lower scores were typical among the youngest (18 years) and oldest (>60 years) age groups. These trends suggest that oral behaviors may be less frequent at the age extremes, although the differences were not statistically significant.

Regarding gender, the analysis revealed no statistically significant difference in total OBC scores between women (M = 22.63, SD = 10.30) and men (M = 21.75, SD = 10.19;

p = 0.456) (

Table 3). Overall, both groups displayed comparable levels of self-reported oral behaviors.

A summary of the total OBC score comparisons by gender and environment of origin is presented in

Table 3, while detailed statistics for individual OBC-21 items are provided in

Supplementary Table S3.

p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Regarding the risk level, 147 women (40.50%) were classified as high risk, while 216 (59.50%) were categorized as low risk. Among men, 70 (74.47%) were classified as low risk, whereas only 24 (25.53%) were categorized as high risk.

Statistically significant gender differences were identified for the following individual behaviors: OBC16 (“chewing food on one side only”) (p = 0.008); OBC18 (“sustained talking”) (p = 0.014); OBC19 (singing) (p = 0.021); and OBC7 (“hold or jut jaw forward or to the side) (p = 0.027). All these oral habits were more frequently observed in women.

No significant differences were found in total OBC scores between participants from urban and rural areas. Among the 326 participants from urban areas, 190 (58.26%) were classified as low risk, while 136 (41.72%) were categorized as high risk. In rural areas, the difference between the two risk levels was more pronounced, with 64.40% of participants classified as low risk and only 35.60% classified as high risk.

However, a statistically significant difference was observed regarding forceful pressing of the teeth with the tongue (

p = 0.04) (

Supplementary Table S3).

4. Discussion

The present study evaluated oral behaviors among 459 Romanian adults using the standardized OBC-21 questionnaire. The results revealed a moderate prevalence of oral behaviors, with postural and involuntary habits—such as sleeping in positions that exert pressure on the jaw, eating between meals, and unilateral chewing—being the most frequent. Although no significant differences emerged in total OBC scores between genders, certain individual behaviors differed significantly. Younger adults (20–49 years) displayed slightly higher scores, suggesting a greater behavioral intensity within this age range.

The study sample (

n = 459) enabled exploratory analyses of behavioral distribution by demographic factors. While the predominance of women and younger participants limits external generalizability, it mirrors patterns observed in self-reported health surveys, where these groups typically demonstrate higher participation rates. This enhances the study’s internal validity and aligns with similar international research [

11,

12,

13].

The OBC-21 utilized in this study was initially developed by Ohrbach and colleagues to evaluate oral behaviors during wakefulness and was subsequently adapted into its current form [

14]. A study conducted by van der Meulen et al. (2014) reported significant correlations between OBC scores and facial pain intensity, supporting its construct validity [

15]. Additionally, the authors reported adequate internal consistency and an enhanced ability to distinguish between voluntary and involuntary behaviors, thereby recommending it as a reliable screening tool.

The OBC-21, developed by Ohrbach and colleagues to evaluate daytime oral behaviors, has demonstrated good reliability and construct validity [

14,

15]. The Romanian version used in this study, translated by the principal investigator, included minimal linguistic adaptations for clarity. Although not formally validated, its use was meth-odologically justified in this exploratory context, given the international acceptance of the instrument and its integration into TMD assessment protocols [

16].

Beyond the validity of the instrument itself, the administration of the questionnaire was carefully planned to minimize sampling biases. To maximize participation and enhance the representativeness of our sample, we administered the Oral Behavior Checklist (OBC-21) using both traditional paper-based methods and an online format. This dual approach allowed us to reach participants with varying preferences and accessibility. Additionally, we employed a multiregional recruitment strategy, with the principal investigator visiting multiple regions across Romania to engage participants directly and collaborate with other clinicians in different areas. This approach aimed to capture a broader geographic distribution, ensuring that the sample reflected diverse adult populations and regional contexts within the country. While convenience sampling inherently carries some limitations regarding representativeness, these efforts helped mitigate potential biases and strengthened the descriptive value of the study.

This strategy is methodologically supported by the principles of the Tailored Design Method, which recommend adapting the data collection process to standardize the respondent experience and maximize response rates, while maintaining the quality of the collected data [

17].

Overall, the distribution of total OBC-21 scores indicates moderate behavioral variability, with a tendency toward higher frequencies among younger adults. This pattern may reflect psychosocial and lifestyle factors associated with active life stages and aligns with previous findings that highlight age as a determinant of oral behavioral expression [

13].

These findings are consistent with observations reported by other researchers who identified a higher prevalence of oral behaviors among young adults (18–29 years). Their study, based on 1424 clinical cases, classified 43.3% of participants as high-risk (OBC score > 24), a proportion slightly above that observed in our sample (39.9%) [

13]. The difference likely reflects contextual variations: the present study included predominantly asymptomatic individuals, whereas the clinical population examined by Reda et al. comprised subjects more susceptible to stomatognathic dysfunctions. This under-scores the importance of considering population characteristics when interpreting prevalence data.

At the population level, oral behaviors appear to be common even in the absence of pain or evident dysfunction [

18]. This highlights the importance of behavioral screening for early prevention, particularly among individuals at increased risk of temporomandibular disorders.

From a clinical standpoint, the score distribution suggests a relatively homogeneous behavioral pattern, with a small subgroup displaying intense and potentially persistent oral behaviors. Identifying this subgroup is essential for early intervention and risk stratification [

19,

20]. The variability observed in OBC-21 scores reflects the multifactorial etiology of these behaviors, influenced by psychological, lifestyle, and demographic factors.

Although total scores did not differ significantly between genders, several individual behaviors—including unilateral chewing, sustained talking, and object biting—were reported more frequently by women. This aligns with previous findings suggesting that women may display greater behavioral reactivity to stress and heightened somatic awareness, potentially mediated by personality traits and coping strategies [

21,

22]. Conversely, the absence of significant gender differences in total OBC scores contrasts with findings from an Italian clinical study reporting higher female scores [

13]. These discrepancies likely arise from contextual differences between community-based and clinical samples and emphasize the need for nuanced interpretation of gender-related pat-terns in oral behaviors.

Recent studies indicate that many adults exhibit oral behaviors—often unconsciously—that can contribute to dental wear, occlusal imbalance, and masticatory muscle overload, even in the absence of evident symptoms [

5,

23]. The involuntary nature of such actions, including jaw clenching, unilateral chewing, or postural habits, makes them difficult to detect and control in everyday life.

These behaviors tend to manifest selectively, with nocturnal and postural habits being more frequently reported than consciously controlled activities, suggesting only partial awareness of the parafunctional phenomenon [

13]. In the present study, the most frequent behaviors—side sleeping and unilateral chewing—are consistent with previous literature identifying similar trends in young adults [

24,

25]. Side sleeping, in particular, has been associated with increased temporomandibular joint (TMJ) loading, pain, and reduced mouth opening, emphasizing its potential clinical impact [

25].

Unilateral chewing and teeth clenching have also been linked to joint sounds and muscular tension [

24]. Their repetitive, often unnoticed occurrence highlights the importance of early identification through both self-report tools and clinical evaluation.

Sustained talking (OBC18) may also reflect overuse of the stomatognathic system in daily activities. Professions involving prolonged speaking or oral exertion—such as teaching or playing wind instruments—can exacerbate muscle fatigue and contribute to functional imbalance, particularly under psychological stress, which is known to increase masticatory muscle activity [

21].

These findings reinforce the clinical relevance of oral behaviors observed in the current sample, highlighting their potential etiopathogenetic role in the development of stomatognathic dysfunctions-even in the absence of a formal clinical diagnosis. Awareness and early education, particularly regarding sleep and postural habits, should be integrated into preventive and diagnostic protocols to mitigate long-term functional risks.

Another frequently reported behavior was eating between meals, a potential indicator of imbalances in dietary patterns or compensatory behaviors in response to stress. Although seemingly benign, this type of repetitive activity may contribute to overloading the masticatory muscles and the temporomandibular joint, particularly in the cumulative context of other parafunctional habits.

Nocturnal bruxism (OBC1), though less prevalent, remains clinically relevant. As an involuntary behavior, it warrants further evaluation through objective diagnostic methods or correlation with clinical signs such as dental wear and muscle tenderness [

26].

Taken together, these findings suggest that even mild and seemingly harmless oral behaviors may exert a cumulative effect on the stomatognathic system. Their association with psychosocial stress underscores the need for systematic behavioral assessment using standardized tools such as the OBC-21, which should be integrated into preventive and diagnostic practice.

Future research should adopt longitudinal designs to track behavioral dynamics over time and identify predictive factors. Combining validated self-report instruments with objective measures (e.g., electromyography, occlusal analysis, or TMJ assessments) could yield a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between oral behaviors and stomatognathic dysfunctions.

Moreover, the psychological dimension of these behaviors warrants further exploration. Emerging evidence links chronic stress and anxiety to increased orofacial activity [

19,

27,

28]. Future studies integrating the OBC-21 with standardized psychological screening tools (e.g., GAD-7, PHQ-9) could clarify these bidirectional relationships and support the development of interdisciplinary prevention and intervention strategies.

Relevant and promising future research involves exploring the relationship between oral behaviors and mental health, particularly symptoms of depression and anxiety. Emerging evidence links chronic stress and anxiety to increased orofacial activity [

19,

27,

28]. Future studies integrating the OBC-21 with standardized psychological screening tools (e.g., GAD-7, PHQ-9) could clarify these bidirectional relationships and support the development of integrated preventive interventions.

Overall, the present findings offer a relevant framework for understanding behavioral patterns in the general population and highlight the need for further analytical and experimental studies. Future research should focus on identifying causal mechanisms and evaluating the effectiveness of preventive interventions through longitudinal or randomized controlled designs. Such efforts would strengthen the evidence base for behavioral risk assessment and contribute to developing tailored strategies for adult oral health in Romania.

The findings of this study have important implications for public health and preventive dentistry in Romania. The moderate prevalence of oral behaviors observed in the general population, even in the absence of overt temporomandibular dysfunction, underscores the need to incorporate behavioral assessment into routine dental care. Early identification of maladaptive oral habits can facilitate timely counseling, reduce the risk of chronic orofacial pain, and improve long-term oral function. Furthermore, public health strategies should prioritize patient education on stress management, posture, and sleep hygiene, as these are modifiable determinants of oral behaviors. Implementing national or regional screening initiatives using standardized instruments such as the OBC-21 could strengthen preventive programs and enhance understanding of behavioral risk factors in oral health across Romania.

The classification of participants into low- and high-risk groups based on OBC-21 scores offers valuable insight into the spectrum of behavioral vulnerability within the general population. This differentiation is not merely statistical but holds clinical relevance, as it may guide individualized preventive and therapeutic approaches in dental practice.

For individuals categorized as low risk, the dentist’s role should primarily focus on preventive counseling and behavioral reinforcement. These patients typically exhibit mild or occasional oral habits that may not currently cause dysfunction but could become problematic over time. Providing targeted education on posture, stress management, and awareness of oral behaviors—alongside routine monitoring during regular dental visits—can help prevent the escalation of such habits and promote long-term functional stability.

In contrast, patients identified as high risk require a more comprehensive and proactive approach. Dentists should conduct detailed functional assessments of the temporomandibular system, evaluate potential muscle or joint involvement, and explore psychosocial factors contributing to these behaviors. Early interventions, including behavioral modification strategies, physiotherapy, or interdisciplinary collaboration with mental health professionals, may be indicated to address underlying stress-related mechanisms. This individualized, risk-based management can enhance the early detection of temporomandibular dysfunction and reduce its long-term clinical impact.

In summary, the present findings emphasize that oral behaviors are highly prevalent among adults, even in the absence of temporomandibular disorders. Integrating behavioral screening and counseling into routine dental practice represents a key step toward early detection, prevention, and improved long-term functional outcomes.

Study Limitations

The use of a multiregional convenience sampling strategy does not ensure full representativeness of the Romanian adult population and may introduce selection bias. Therefore, the results should be interpreted as exploratory.

A second limitation pertains to the unbalanced structure of the sample, characterized by a predominance of women and younger participants. This demographic profile, while common in self-reported health surveys, may limit the external validity of the results. Consequently, future large-scale studies should encompass diverse regions of Romania reflect the true distribution of oral behaviors within the Romanian population.

Also, the questionnaire employed (OBC-21) was administered in a Romanian-translated version without formal psychometric validation. Although the instrument is standardized and internationally recognized, the absence of rigorous cultural adaptation in the Romanian context remains an important aspect that should be addressed in future research.

The study also relied exclusively on self-reported data, which may be subject to recall bias, as participants might not accurately remember or may underreport the frequency of certain behaviors. Social desirability bias cannot be excluded either, as some participants might have minimized the occurrence of behaviors perceived as undesirable or socially inappropriate [

29]. Moreover, the absence of clinical confirmation represents a limitation of the present research. Future studies should correlate OBC-21 scores with clinical examinations to validate the accuracy of self-reported data and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the clinical significance of these behaviors. Nevertheless, the anonymous nature of data collection and the use of a standardized, validated tool partially mitigate these risks.

Finally, an additional limitation concerns the assessment of mental health. This was not performed using standardized psychiatric instruments. Instead, exclusion relied on self-reported information provided in the medical history form completed at the first dental visit, where participants disclosed ongoing treatments or medical conditions, including psychiatric care. While this approach offered a practical and ethically acceptable screening method, it does not replace a structured mental health evaluation and may limit the precision of participant selection.

A strength of the present study is that deleterious oral habits have not previously been investigated in a Romanian population, which provides originality and scientific relevance to the research. In addition, the analysis was conducted on a statistically significant number participants that supports the validity of results and confers international relevance. Furthermore, the use of an internationally validated assessment tool strengthens the methodological robustness of the study.

5. Conclusions

The present study investigated the prevalence and patterns of oral behaviors among the general adult population in Romania, utilizing the OBC-21 questionnaire. The findings indicate a moderate expression of these behaviors, with interindividual variability and higher scores observed among young adults (20–49 years).

These findings underscore that oral behaviors are common even among asymptomatic adults, reinforcing their relevance as early behavioral markers of functional risk and as potential targets for preventive and educational interventions.

Although the total score did not differ significantly between genders, the analysis of individual items revealed relevant differences, suggesting gender-related influences. The most frequently reported behaviors were postural, alimentary, and those associated with unconscious diurnal activities.

The heterogeneity of scores and the presence of these behaviors even in the absence of clinical symptoms underscore the relevance of behavioral screening and self-monitoring, particularly within at-risk groups. The results also highlight the importance of employing standardized instruments such as the OBC-21 in both clinical assessment and research on parafunctional behaviors.

Overall, oral behaviors appear to represent a complex, multifactorial phenomenon that requires integrated approaches combining screening, education, and prevention. Incorporating behavioral assessment into clinical protocols—even in the absence of TMD symptoms—may enhance early detection, prophylaxis, and management of related dysfunctions.

By providing population-level normative data for Romanian adults, this study fills a significant regional knowledge gap and contributes novel epidemiological evidence supporting the integration of behavioral evaluation into routine dental and public health practice. These insights also emphasize the need for interdisciplinary collaboration to strengthen behavioral awareness and early intervention at both clinical and policy levels.

These data could serve as a solid foundation for future research exploring the interaction between psychological and clinical dimensions, such as stress, anxiety, or temporomandibular dysfunctions, aimed at developing personalized strategies for early prevention and intervention within oral and mental health frameworks.