Medication Errors in Saudi Arabian Hospital Settings: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Active failures (slips—look-alike sound-alike medications, memory lapses; lapse—dispensing wrong drug, faulty dose checking; mistake—wrong packaging, preparation error; violation—poor adherence to protocol, breaking hospital rules);

- Error-producing conditions (miscommunication of drug orders; illegible prescription or records; wrong medication preparation by pharmacists; lack of knowledge; poor communication; lack of patient information);

- Latent failures (lack of educational activities; performance deficit; pharmacists not available 24 h a day; low staffing; poor drug stocking and delivery).

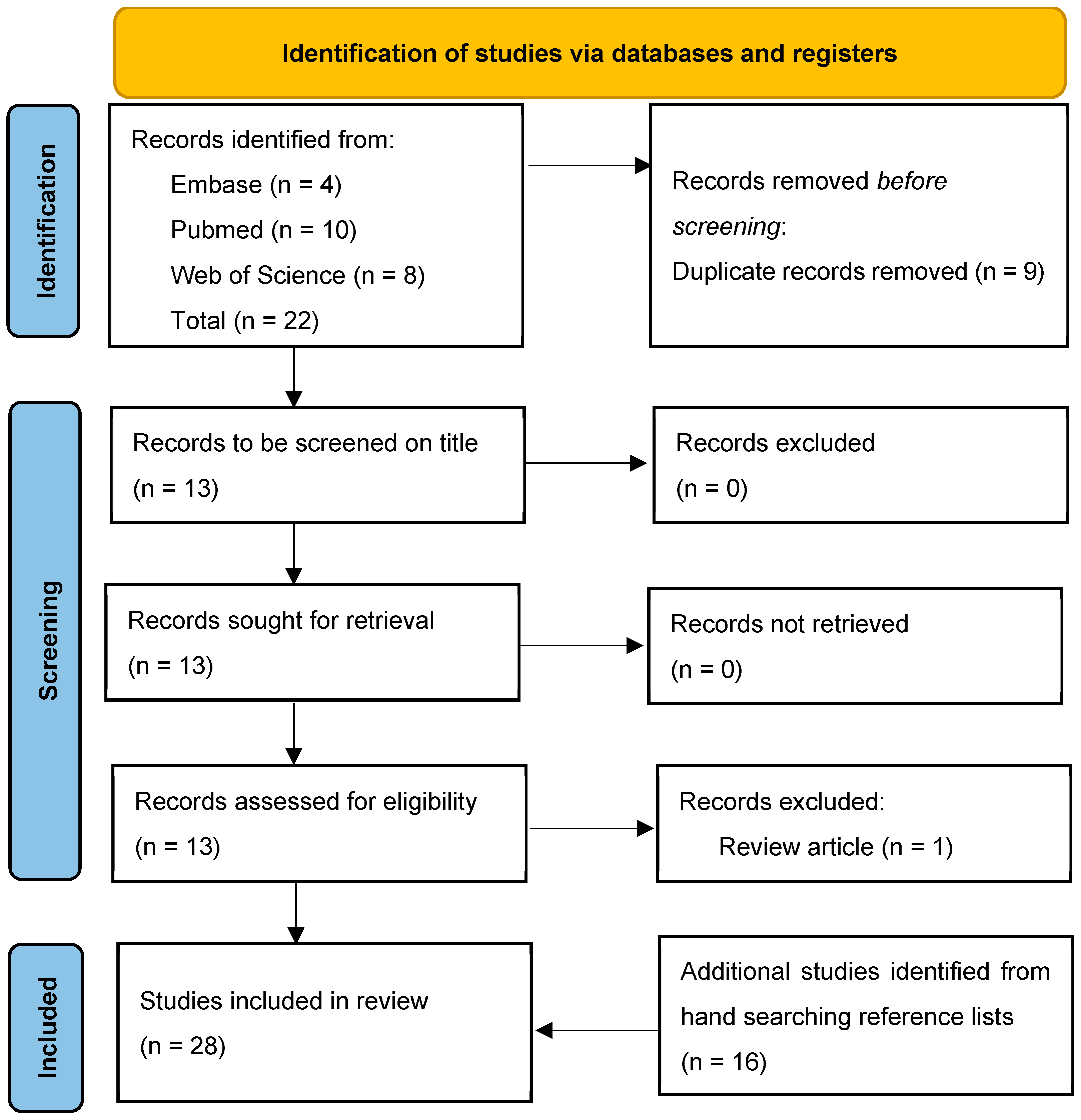

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Types of Medication Errors

3.2. Strategies to Reduce Medication Errors

4. Discussion

4.1. Strength and Limitations

4.2. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCCMERP). About Medication Errors. Available online: https://www.nccmerp.org/about-medication-errors (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Institute of Medicine. Preventing Medication Errors; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; Available online: https://www.nationalacademies.org/news/2006/07/medication-errors-injure-one-point-five-million-people-and-cost-billions-of-dollars-annually-report-offers-comprehensive-strategies-for-reducing-drug-related-mistakes (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Abu Esba, L.C.; Alqahtani, N.; Thomas, A.; Shams El Din, E. Impact of medication reconciliation at hospital admission on medication errors. Pharmacy 2018, 16, 1275. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D.W.; Spell, N.; Cullen, D.J.; Burdick, E.; Laird, N.; Petersen, L.A.; Small, S.D.; Sweitzer, B.J.; Leape, L.L. The Costs of Adverse Drug Events in Hospitalized Patients. JAMA 1997, 277, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aspden, P.; Wolcott, J.A.; Bootman, J.L.; Cronenwett, L.R. Preventing Medication Errors; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Aljadhey, H.; Mahmoud, M.A.; Hassali, M.A.; Alrasheedy, A.; Alahmad, A.; Saleem, F.; Bates, D.W. Challenges to and the future of medication safety in Saudi Arabia: A qualitative study. Saudi Pharm. J. 2013, 21, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, D.W.; Cullen, D.J.; Laird, N.; Petersen, L.A.; Small, S.D.; Servi, D.; Laffel, G.; Sweitzer, B.J.; Shea, B.F.; Hallisey, R.; et al. Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events: Implications for prevention. JAMA 1995, 274, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Third WHO Global Patient Safety Challenge: Medication without Harm. Available online: https://www.who.int/initiatives/medication-without-harm (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Chalasani, S.H.; Syed, J.; Ramesh, M.; Patil, V.; Kumar, T.P. Artificial intelligence in the field of pharmacy practice: A literature review. Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 2023, 12, 100346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.; Saei, S.; Khouzani, S.J.; Rostami, M.E.; Rahmannia, M.; Manzelat, A.M.; Bayanati, M.; Rasti, S.; Rajabloo, Y.; Ghorbani, H.; et al. Emerging Technologies in Medicine: Artificial Intelligence, Robotics, and Medical Automation. Kindle 2023, 3, 1–184. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dhawailie, A.A. Inpatient prescribing errors and pharmacist intervention at a teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2011, 32, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljadhey, H.; Mahmoud, M.A.; Mayet, A.; Alshaikh, M.; Ahmed, Y.; Murray, M.D.; Bates, D.W. Medication safety practices in hospitals: A national survey in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm. J. 2013, 21, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsulami, Z.; Conroy, S.; Choonara, I. Medication errors in the Middle East countries: A systematic review of the literature. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 69, 995–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobaiqy, M.; Stewart, D. Exploring health professionals’ experiences of medication errors in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2013, 35, 542–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, R.; Bates, D.W.; Landrigan, C.; McKenna, K.J.; Clapp, M.D.; Federico, F.; Goldmann, D.A. Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. JAMA 2001, 285, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leape, L.L.; Bates, D.W.; Cullen, D.J.; Cooper, J.; Demonaco, H.J.; Gallivan, T.; Seger, D.L. Systems analysis of adverse drug events. JAMA 1998, 274, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.; Paudyal, V.; Maclure, K.; Pallivalapila, A.; McLay, J.; Elkassem, W.; Al Hail, M.; Stewart, D. Medication errors in hospitals in the Middle East: A systematic review of prevalence, nature, severity and contributory factors. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 75, 1269–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reason, J. Human error: Models and management. BMJ 2000, 320, 768–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; The PRISMA-P Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P): Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015, 349, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLure, K.; Tobaiqy, M.; Medication Errors in Saudi Arabian Hospital Settings: A Systematic Review Protocol. PROSPERO 2024 CRD42024556487. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42024556487 (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghezaywi, Z.; Alali, H.; Kazzaz, Y.; Ling, C.M.; Esabia, J.; Murabi, I.; Mncube, O.; Menez, A.; Alsmari, A.; Antar, M. Targeting zero medication administration errors in the pediatric intensive care unit: A Quality Improvement project. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2024, 81, 103595, Erratum in Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2024, 83, 103687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhur, A.; Alhur, A.A.; Al-Rowais, D.; Asiri, S.; Muslim, H.; Alotaibi, D.; Al-Rowais, B.; Alotaibi, F.; Al-Hussayein, S.; Alamri, A.; et al. Enhancing Patient Safety Through Effective Interprofessional Communication: A Focus on Medication Error Prevention. Cureus 2024, 16, e57991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.H.; Alhammad, A.M.; Alshaya, A.I.; Alkhani, N.; Alenazi, A.O.; Aljuhani, O. Characteristics of Critical Care Pharmacy Services in Saudi Arabia. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2023, 16, 3227–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assiri, G.A.; Bin Shihah, A.S.; Alkhalifah, M.K.; Alshehri, A.S.; Alkhenizan, A.H. Identification and Characterization of Preventable Adverse Drug Events in Family Medicine Clinics from Central Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Med. Med. Sci. 2023, 11, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzaagi, I.A.; Alshahrani, K.M.; Abudalli, A.N.; Surbaya, S.; Alnajrani, R.; Ali, S. The Extent of Medication Errors During Hajj in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2023, 15, e41801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alothmany, H.N.; Bannan, D.F. Implementation Status and Challenges Associated With Implementation of the Targeted Medication Safety Best Practices in a Tertiary Hospital. Cureus 2023, 15, e45552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhossan, A.; Alhuqbani, W.; Abogosh, A.; Alkhezi, O.; Alessa, M.; Ahmad, A. Inpatient Pharmacist Interventions in Reducing Prescription-Related Medication Errors in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Farmacia 2023, 71, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rowily, A.; Baraka, M.A.; Abutaleb, M.H.; Alhayyan, A.M.; Aloudah, N.; Jalal, Z.; Paudyal, V. Patients’ views and experiences on the use and safety of directly acting oral anticoagulants: A qualitative study. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2023, 16, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanazi, M.F.; Shahein, M.I.; Alsharif, H.M.; Alotaibi, S.M.; Alanazi, A.O.; Alanazi, A.O.; Alharbe, U.A.; Almfalh, H.S.S.; Amirthalingam, P.; Hamdan, A.M.; et al. Impact of automated drug dispensing system on patient safety. Pharm. Pract. 2022, 20, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almuqbil, M.; Alrojaie, L.; Alturki, H.; Alhammad, A.; Alsharawy, Y.; Alkoraishi, A.; Almuqbil, A.; Alrouwaijeh, S.; Wajid, S.; Al-Arifi, M.N. The role of drug information centers to improve medication safety in Saudi Arabia—A study from healthcare professionals’ perspective. Saudi Pharm. J. 2022, 30, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomi, Y.A.; Imam, M.S.; Abdel-Sattar, R.M.; Alduraibi, G.M.A.; Alotaibi, A.S.M. Safety Culture of Physicians’ Medication in Saudi Arabia. J. Pharm. Negat. Results 2022, 13, 1201–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, S.; Almimone, M.; Alatawi, S.; Shahin, M.A.H. Medication errors by nurses at medical-surgical departments of a Saudi hospital. J. Pharm. Negat. Results 2022, 13, 3143–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyami, M.H.; Naser, A.Y.; Alswar, H.S.; Alyami, H.S.; Alyami, A.H.; Al Sulayyim, H.J. Medication errors in Najran, Saudi Arabia: Reporting, responsibility, and characteristics: A cross-sectional study. Saudi Pharm. J. 2022, 30, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, T.; Machudo, S.; Eid, R. Interruptions during medication work in a Saudi Arabian hospital: An observational and interview study of nurses. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2022, 54, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, S.I. A retrospective analysis of near-miss incidents at a tertiary care teaching hospital in Riyadh, KSA. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2022, 17, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egunsola, O.; Ali, S.; Al-Dossari, D.S.; Alnajrani, R.H. A Retrospective Study of Pediatric Medication Errors in Saudi Arabia. Hosp. Pharm. 2021, 56, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani, A.A.; Alwhaibi, M.M.; Asiri, Y.A.; Kamal, K.M.; Alhawassi, T.M. Description of pharmacists’ reported interventions to prevent prescribing errors among in hospital inpatients: A cross sectional retrospective study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alwadie, A.F.; Naeem, A.; Almazmomi, M.; Baswaid, M.A.; Alzahrani, Y.A.; Alzahrani, A.M. A Methodological Assessment of Pharmacist Therapeutic Intervention Documentation (TID) in a Single Tertiary Care Hospital in Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Pharmacy 2021, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljuaid, M.; Alajman, N.; Alsafadi, A.; Alnajjar, F.; Alshaikh, M. Medication Error During the Day and Night Shift on Weekdays and Weekends: A Single Teaching Hospital Experience in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 2571–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharaibi, M.A.; Alhifany, A.A.; Asiri, Y.A.; Alwhaibi, M.M.; Ali, S.; Jaganathan, P.P.; Alhawassi, T.M. Prescribing errors among adult patients in a large tertiary care system in Saudi Arabia. Ann. Saudi Med. 2021, 41, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayamkani, A.K.; Bayazeed, T.K.A.; Aljuhani, M.S.M.; Koshak, S.M.S.; Khan, A.A.; Iqubal, S.M.S.; Ikbal, A.R.; Maqbul, M.S.; Mayana, N.K.M.; Begum, S.M.B. A Study of Prescribing Errors in a Private Tertiary Care Hospital in Saudi Arabia. J. Young Pharm. 2020, 12, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aseeri, M.; Banasser, G.; Baduhduh, O.; Baksh, S.; Ghalibi, N. Evaluation of Medication Error Incident Reports at a Tertiary Care Hospital. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsulami, S.L.; Sardidi, H.O.; Almuzaini, R.S.; Alsaif, M.A.; Almuzaini, H.S.; Moukaddem, A.K.; Kharal, M.S. Knowledge, attitude and practice on medication error reporting among health practitioners in a tertiary care setting in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2019, 40, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, S.M.; Alakhali, K.M.; Al-Worafi, Y.M. Medication errors in a health care facility in southern Saudi Arabia. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2019, 18, 1119–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAzmi, A.; Ahmed, O.; Alhamdan, H.; AlGarni, H.; Elzain, R.M.; AlThubaiti, R.S.; Aseeri, M.; Al Shaikh, A. Epidemiology of Preventable Drug-Related Problems (DRPs) among Hospitalized Children at KAMC-Jeddah: A Single-Institution Observation Study. Drug Healthc. Patient Saf. 2019, 11, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhawassi, T.M.; Alatawi, W.; Alwhaibi, M. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications use among older adults and risk factors using the 2015 American Geriatrics Society Beers criteria. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanazi, S.A.; Al Amri, A.; Almuqbil, M.; Alroumi, A.; Gamal Mohamed Alahmadi, M.; Obaid Ayesh Alotaibi, J.; Mohammed Sulaiman Alenazi, M.; Hassan Mossad Alahmadi, W.; Hassan Saleh Al Bannay, A.; Khaled Ahmad Marai, S.; et al. Use of potentially inappropriate medication for elderly patients in tertiary care hospital of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm. J. 2024, 32, 102015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, H.; Alnasser, M.; Assiri, A.; Tawhari, F.; Bakkari, A.; Mustafa, M.; Alotaibi, W.; Asiri, A.; Khudari, A.; Alshreem, A.; et al. Utilization of Direct Oral Anticoagulants in a Saudi Tertiary Hospital: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 10076–10081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fernández, A.; Gómez, F.; Curcio, C.L.; Pineda, E.; Fernandes de Souza, J. Prevalence and impact of potentially inappropriate medication on community-dwelling older adults. Biomedica 2021, 41, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, F.; Chen, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Feng, Q.; Chen, X. Prevalence of Use of Potentially Inappropriate Medications Among Older Adults Worldwide: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2326910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabri, F.F.; Liang, Y.; Alhawassi, T.M.; Johnell, K.; Möller, J. Potentially Inappropriate Medications in Older Adults—Prevalence, Trends and Associated Factors: A Cross-Sectional Study in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berwick, D.M.; Calkins, D.R.; McCannon, C.J.; Hackbarth, A.D. The 100,000 lives campaign: Setting a goal and a deadline for improving health care quality. JAMA 2006, 295, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronovost, P.J.; Needham, D.; Berenholtz, S.; Sinopoli, D.; Chu, H.; Cosgrove, S.; Sexton, B.; Hyzy, R.; Welsh, R.; Roth, G.; et al. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 2725–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, K.M.; Lewton, E.; Rosenthal, M.M. Communication failures: An insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad. Med. 2004, 79, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, E.G.; Keohane, C.A.; Yoon, C.S.; Ditmore, M.; Bane, A.; Levtzion-Korach, O.; Moniz, T.; Rothschild, J.M.; Kachalia, A.B.; Hayes, J.; et al. Effect of bar-code technology on the safety of medication administration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1698–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manias, E.; Aitken, R.; Dunning, T. Nurses’ medication work: What’s happening in the black box? Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 78, 487–497. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn, L.T.; Corrigan, J.M.; Donaldson, M.S. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, C.A.; Raehl, C.L.; Franke, T. Pharmacist staffing and the quality of pharmaceutical care in hospitals. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2001, 58, 747–753. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D.W.; Leape, L.L.; Cullen, D.J.; Laird, N.; Petersen, L.A.; Teich, J.M.; Burdick, E.; Hickey, M.; Kleefield, S.; Shea, B.; et al. Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors. JAMA 1998, 280, 1311–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, T.K.; Weingart, S.N.; Borus, J.; Seger, A.C.; Peterson, J.; Burdick, E.; Seger, D.L.; Shu, K.; Federico, F.; Leape, L.L.; et al. Adverse drug events in ambulatory care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1556–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leape, L.L.; Brennan, T.A.; Laird, N.; Lawthers, A.G.; Localio, A.R.; Barnes, B.A.; Hebert, L.; Newhouse, J.P.; Weiler, P.C.; Hiatt, H.H. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study II. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 324, 377–384. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D.W.; Boyle, D.L.; Vander Vliet, M.B.; Schneider, J.; Leape, L.L. Relationship between medication errors and adverse drug events. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1995, 10, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, C.A.; Raehl, C.L.; Pitterle, M.E.; Franke, T. The impact of clinical pharmacists on the cost of drug therapy in a hospital setting. Pharmacotherapy 2002, 22, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockley, S.W.; Cronin, J.W.; Evans, E.E.; Cade, B.E.; Lee, C.J.; Landrigan, C.P.; Rothschild, J.M.; Katz, J.T.; Lilly, C.M.; Stone, P.H.; et al. Effect of reducing interns’ weekly work hours on sleep and attentional failures. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1829–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, S.J.; Dy, S.M.; Rosen, M.A. Team-training in healthcare: A narrative synthesis of the literature. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2014, 23, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkey, P.; Cunningham, J.; Bisping, D.S. Improving medication reconciliation in the outpatient setting. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2007, 33, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobaiqy, M.; McLay, J.; Ross, S. Foundation year 1 doctors and clinical pharmacology and therapeutics teaching: A retrospective view in light of experience. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2007, 64, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Likic, R.; Maxwell, S.R. Prevention of medication errors: Teaching and training. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009, 67, 656–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author, Year, Study Type, Reference | Population and Hospital Type | Location of Medication Errors, Medicines Involved, Outcome, and Severity of Medication Errors | Incidence/Prevalence, Types of Medication Errors, and Contributing Factors | Preventive or Improvement Strategies Implemented to Reduce Medication Errors | Outcomes and Effectiveness of These Strategies | Limitations/Biases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghezaywi et al. (2024) Quality Improvement Project [23] | 1000 patients Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU). | Hospital’s electronic medical record and nursing information systems | 49 medication errors: wrong time errors (n = 23), improper dose errors (n = 8), omission errors (n = 6), prescribing errors (n = 6), wrong medication preparation errors (n = 2), wrong administration technique errors (n = 2), and other medication errors (n = 2). | -Awareness campaign; -Reinforcement of closed-loop medication administration system utilization; -Independent double-check simulations; -Pediatric drug library utilization and electronic order sets. | The study reported zero medication errors per 1000 patient days in the first quarter of 2022. | Reliance on self-reported data and direct observation may introduces potential reporting and observer bias. A single PICU at one hospital limits the generalizability of findings to other healthcare settings. The potential variability in the effectiveness of interventions across different PICU contexts. |

| Alhur et al. (2024) Cross-Sectional Study [24] | 1165 healthcare professionals. Female (n = 763, 65.49%). Various settings within Saudi Arabia hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies. | Healthcare workers | Prescription errors (n = 233, 52.70%), dispensing errors (n = 40, 16.74%), documentation errors (n = 34, 16.65%), monitoring errors (n = 24, 13.91%). Medications inappropriate for the elderly should be used with caution or avoided. | Improving the quality of communication among healthcare professionals. | Showing that transparent and constructive environments significantly reduce medication errors. | Self-reported data may lead to overestimation of communication efficacy and under-reporting of errors. The cross-sectional design limits causality and generalizability. |

| Ismail et al. (2023) Cross-Sectional Study [25] | 23 CCPs. Hospitals in Saudi Arabia. | Critical care pharmacists | Having 1–2 CCPs per critically ill patient. | Need for standardizing CCP-to-patient ratios and implementing technology to optimize services. | Emphasizes the need for standardized CCP-to-patient ratios and additional support for CCPs to expand their services | Response bias may have occurred as respondents were more likely to participate if their pharmacy departments had established clinical pharmacy services. |

| Assiri et al. (2023) Retrospective Observational Study [26] | 117 adult females (n = 64, 54.7%). Family medicine clinics in King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center. | Pharmacists. Of 117 patients, (n = 9, 7.7%) experienced preventable adverse drug events. All pADE cases involved OTC medications and polypharmacy. Specific outcomes: asthma (2 cases), β-blocker (4 cases), and single cases for warfarin/INR, lithium/lithium level, new oral anticoagulant/antiplatelet, and aspirin/antiplatelet. | 9 patients (7.7%) experienced pADE. | Need for a multi-center study on clinically important medication errors at prescribing and monitoring stages to develop quality improvement programs. | This study reports the period prevalence of patients with pADEs in family medicine clinics. | Limited generalizability due to the single-center study. Retrospective assessments were constrained by available data, and information biases may have influenced severity perception. |

| Alzaagi et al. (2023) Retrospective Observational Study [27] | 3210 prescriptions Mina Al Wadi Hospital | Intensive care unit, emergency room, medical ward, and outpatient department. Of the 43 medication errors reported, 97.67% were near misses, while only 2.32% reached patients without causing injury. | There were 43 medication errors reported, with the following causes: lack of drug information (58.14%), wrong drugs (23.25%), workload issues (23.25%), frequency (18.60%), and medication issues (18.60%). | The study found that medication errors were in line with global standards, often preventable, and rarely reached pilgrims. | The most common error was incorrect medication, mainly due to lack of drug information. | Voluntary reporting at a single hospital likely leads to the under-reporting of medication errors. The study was conducted in a temporary healthcare setting during Hajj; thus, it lacks generalizability. |

| Alothmany et al. (2023) Qualitative Study [28] | 8 interviews, male (n = 3), female (n = 5). Pharmacy department of a tertiary care hospital. | Pharmaceutical Services. | -Improving high-alert medication safety (85.7%); -Having antidotes available (75%); -Verifying sterile preparations (75%); -Maximizing barcode verification (12.5%). | Barriers included lack of knowledge, motivation, and environmental resources. Healthcare providers need knowledge, motivation, and resources to implement best practices effectively. | The study’s single-center design and small sample size (eight managers, with only five interviewed) may limit the generalizability of the findings, though all participants completed the survey. | |

| Alhossan et al. (2023) Retrospective Observational Study [29] | A total of 9215 reports on ordering and prescribing errors were collected from 6 tertiary care hospitals in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. | Errors occurred primarily in the ICU (n = 3919, 42.5%), followed by the NICU (n = 3207, 34.8%), CCU (n = 1336, 14.5%), and PICU (8.5%). | Out of 9215 medication orders, incomplete orders (n = 1928, 21%), lacking drug information (n = 1503, 16%), dosing schedule errors (n = 1290, 14%), duplicate drug class errors (n = 914, 10%), and wrong dose errors (n = 647, 7%). | -Improved medication errors documentation and continuous monitoring. | Emphasize the crucial role of inpatient pharmacists in detecting, reporting, and reducing prescription-related errors. | Including only prescription errors detected by inpatient pharmacists would likely underestimate the true incidence of medication errors. Emphasizing medication safety in the ICU and encouraging error reporting could further reduce these errors. |

| Al Rowily et al. (2023) Qualitative Study [30] | 9 patients, female (n = 3), male (n = 6). Tertiary care hospitals. | Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). | Lack of knowledge on DOACs, difficulty accessing DOACs. | Develop and assess theory-based interventions to enhance patient knowledge and understanding shared decision making. | Effective communication, timely clinic access, availability of medications key to optimizing DOAC utilization safety. | The study’s results, drawn from a limited sample size, may not fully represent the broader patient population. |

| Alanazi et al. (2022) Cross-Sectional Study [31] | 49 clerkship students, female (n = 25) and male (n = 24). Tertiary care hospitals. | Pharmacists. | Daily prescription errors exceeded 10 with automated drug dispensing system (ADDs) at 4.16% and traditional drug dispensing system at 2.11%. | To allocate more time for patient care. | ADDs effectively improved dispensing practices and medication reviews. | Potential selection bias. The study relied on self-reported prescription errors and high-alert medication dispensing rather than incident data analysis. Additionally, the small sample size may not reflect the broader pharmacist community’s views. |

| Almuqbil et al. (2022) Retrospective Observational Study [32] | A total of 243 drug information inquiries were evaluated. Tertiary hospital. | Enquires from pharmacists, physicians, and nurses. Antibiotics (13.6%) were the most common, followed by antihypertensive agents (11.1%), anticoagulants (8.5%), and anticonvulsants (6.8%). | N = 243. Prescribing errors (88.1%) were the most prevented by drug info specialists, followed by dispensing errors (4.5%). About half were near-misses (45.3%), with potential near-misses at 34.6%, only 20.2% were actual errors. | Pharmacists supplying evidence-based information to the inquirer. | This study highlights the role of drug information specialists in preventing medication errors and enhancing patient safety through evidence-based information. | The study’s small sample size from a single institution in Saudi Arabia’s capital may limit generalizability. Reliance on providers’ willingness to report errors might also lead to underestimations. |

| Alomi et al. (2022) Cross-Sectional Study [33] | Out of the 253 responding physicians’ female (n = 72, 60.50%). An electronic self-reported survey of physicians in Saudi Arabia. | Anticoagulants (33.33%) and NSAIDs (32.32%) most reported in medication errors. Sedatives (38.78%) and muscle relaxants (36.73%) were common in ADR cases. Antineoplastics (40.00%) and anti-seizure drugs (39.39%) frequently appeared in look-alike sound-alike issues. | Physicians’ medication safety cultures were insufficient and inconsistent. | Develop medication safety cultures. | It is recommended to revise medication safety culture guidelines and enhance education and training to improve knowledge and practices related to medication safety. | The study’s cross-sectional design involved mostly young doctors with limited experience. |

| Alotaibi et al. (2022) Cross-Sectional Study [34] | A total of 260 nurses participated, with males (n = 177, 68.1%), females (n = 83, 31.9%). KSMC in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | Nurses. | 35% of nurses reported no medication errors. 12.3% reported committing five errors, 11.5% who reported one error during their nursing career. Physicians’ illegible handwriting, incorrect drug dose prescriptions, nurse fatigue. | Medication errors should be documented through incident reports in a confidential, informative, and penalty-free system. | Continuous education and on-the-job training for nurses in medication administration are essential in hospitals. | Participants’ differing insights may be overlooked, and convenience sampling could lead to under-representation, limiting the generalizability of the findings. |

| Alyami et al. (2022) Retrospective Observational Study [35] | All medical records at King Khalid Hospital of Najran region, Saudi Arabia. | Healthcare professionals and departments. Antibiotics, anticoagulants, and antihypertensives. | There were 4860 medication errors: 21.2% involved overdose or underdose, 6.2% inappropriate dosage units, 6.1% therapeutic duplication. Ordering/prescribing/transcribing 66.9%, admin for 28.8%, preparing/dispense 2.9%. | Improving medication ordering, prescribing, and transcribing in hospital settings. | This study highlights common medication errors and provides useful tips for reducing these errors and enhancing patient safety. | The study’s results were drawn from a single hospital, limiting the findings’ generalizability. The study relies on data extracted from electronic medical records, which may miss undocumented or under-reported medication errors. |

| Eid et al. (2022) Prospective Observational Study [36] | A standard paper-based tool and digital stopwatch counted interruptions. Nurses’ sources, secondary tasks, and interruption impacts were considered. Tertiary teaching hospital. | Nurses. | A total of 87 medication-related events occurred, with 182 interruptions accounting for 90%. Interruptions were frequent during medication administration, often in corridors and patients’ rooms. Nurses, medical officers, and impediments were common sources. System failures were linked to clinical and procedural errors. | Using an Omnicell automatic dispensing machine and cabinets in each patient’s room. Wearing a “no-interruption zone” sign, can be tailored to the practice context to reduce interruptions. | 90% of medication work events were interrupted, mostly during administration tasks. | The study’s limitations include convenience sampling, a small sample size, the Hawthorne effect, and data collection during the busy morning shift, limiting generalizability to other contexts. |

| Memon SI. (2022) Retrospective Observational Study [37] | 253 medical records, male (n = 123) female (n = 130). A tertiary care teaching hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. | Admissions and inpatient treatment records. | Out of 248 incidents (98.2%), wrong doses (n = 118, 46.6%), duplicate therapies (n = 69, 27.33%), wrong medications (n = 16, 6.3%). Also, workplace violence and nursing practices. | Near misses should recognized as key targets for continuous quality improvement tools to reduce preoperative incidents in hospitals. | Organizational lapses were identified as critical targets for mitigating perioperative incidents in the hospital. | Near-miss data vary by hospital. A key limitation is the lack of classification based on immediate corrective actions taken. |

| Egunsola et al. (2021) Retrospective Observational Study [38] | 109,382 drugs were ordered. Tertiary hospital in Saudi Arabia. | Healthcare professionals. Intravenous medicines (n = 2985, 32.7%), oral (n = 2199, 24.1%), inhalation (n = 2081, 22.8%). 0.4% reached the patient but caused no harm. | Out of 9123 medication errors: wrong frequency (39.1%), wrong drug (12.5%), wrong concentration or strength (12.4%), and wrong dose (11.1%). | Electronic prescribing system and integrated clinical pharmacists into patient care. | Medication errors are common in pediatric care, particularly with drugs like paracetamol and amoxicillin. | Under-reporting occurred due to fear, time constraints, lack of awareness, and disinterest. Root cause analyses were not conducted, limiting insights into MEs and hindering the development of preventive strategies. |

| Alzahrani et al. (2021) Retrospective Observational Study [39] | A total of 2564 pharmacist interventions related to medication prescribing errors. Tertiary teaching hospital. | Pharmacists. Anti-infectives for systemic use (49.2%) and alimentary tract and metabolism medications (18.2%). | Out of 2564 medication errors, 54.3% were wrong doses and 21.9% were unauthorized prescriptions. | Care coordination and patient safety prioritization through quality improvement initiatives are crucial at all levels of the healthcare system. | Medication errors were common, and pharmacist interventions were crucial in preventing potential patient harm. | The study, conducted in a single tertiary hospital, may have missed some PEs due to incomplete records. Additionally, variations in how pharmacists provided and reported interventions could affect the findings. |

| Alwadie et al. (2021) Prospective Observational Study [40] | 14,144 pharmacists’ interventions were recorded. King Abdulaziz Medical City (KAMC) hospital in Jeddah. | Pharmacist. Perfusion solutions (41%), and antibacterial (35%). | Order entry errors occurred at a rate of 9.1%. The most frequent issue was incorrect dilution, accounting for 40.2% of cases (n = 972). This was followed by dose substitution at 27.7% (n = 665), and duplicate therapy at 10.3% (n = 248). | Routine pharmacist review of inpatient drug therapy is essential for ensuring the quality use of medicines. | Therapeutic Intervention Documentation (TID) holds significant potential to decrease drug-related problems. | Focusing on the most common interventions (93.4%) might overlook less frequent but highly significant interventions. |

| Aljuaid et al. (2021) Retrospective Observational Study [41] | Examining medication errors reported by healthcare practitioners January 2018 and December 2019. Primary, secondary, and tertiary care. | Healthcare practitioners. | Out of 2626 medication errors, 55% were prescribing errors, 14.1% were due to lack of availability, and 10.1% involved delayed medications. Medication errors were more likely to occur during night shift compared to the day shift. | The timing of medication errors is crucial for enhancing medication use and patient safety. | There is a statistically significant relationship between medication errors and the day of the week, with higher incidence during weekdays compared to weekends. | Voluntary reporting, influenced by healthcare providers’ awareness and fear of punitive actions, leads to under-reporting. Cultural differences among nurses also affect the reporting of administration errors. |

| Alharaibi et al. (2021) Retrospective Observational Study [42] | 315,166 prescriptions were screened. Tertiary care. | Medical residents comprised the largest group (52%, n = 2577), followed by specialists (33%, n = 1629). Drugs for the alimentary tract and metabolism accounted for 1156 prescriptions (23.4%). Two-thirds of prescribing errors were harmless to patients. | There were 4934 prescribing errors (1.56%), improper dose (n = 1516, 30.7%), and incorrect frequency (n = 987, 20%). Prescribing errors were linked to inadequate documentation of clinical information. | Future studies should aim to test innovative measures to control these factors and assess their impact on reducing prescribing errors. | Insufficient documentation in electronic health records and the prescription of anti-infectives were the predominant factors predicting PEs. | The study is based on data from a single healthcare setting, which may limit generalizability. The study did not account for the total number of drugs per prescription, which could increase the likelihood of prescribing errors due to polypharmacy. |

| Kayamkani et al. (2020) Retrospective Observational Study [43] | 130 patients Tertiary care hospital. | Healthcare. 27% involved minor drug–drug interactions, 9% were moderate interactions, and 2% were classified as serious drug–drug interactions. | 28% of prescriptions were incomplete, with issues such as missing dose information (7%), inadequate directions (2.7%), and omission of treatment duration (3.5%). | Computerizing the medication process and providing a drug formulary in hospitals can serve as quick references for prescribers. Effective training of newly appointed doctors. | Pharmacists’ roles are crucial in detecting and correcting medication errors, requiring formal acknowledgment and incorporation into a routine monitoring. | The limited number of patient prescriptions from a single tertiary hospital reduces the study’s representativeness and generalizability. |

| Aseeri et al. (2020) Retrospective Observational Study [44] | Analysis was conducted on all reported medication error incidents. Tertiary care center. | Healthcare professionals. Chemotherapeutic agents accounted for 23.6%, anticoagulants for 7.5%, and opiates/narcotics for 4.8% of cases. Near misses (69.3%). | There were 624 medication errors in dispensing/administration, comprising 15% of cases. Further, 13% were due to incorrect dose, 8.9% involved the wrong patient, and 7.5% resulted from dose omission. | Prescribing oral liquid medications exclusively using the metric weight system (e.g., mg). | The hospital medication safety reporting program is a valuable tool for identifying system-based issues in medication management. | The reliance on voluntary reporting may lead to under-reporting or selective reporting of medication errors, introducing bias in the data. The study was conducted in one tertiary care center, so the findings may need to be more generalizable to other institutions or regions. |

| Alsulami et al. (2019) Cross-Sectional Study [45] | 365 participants, 89.3% were female. Healthcare institution. | Pediatric, internal medicine, surgery, family medicine and obstetrics and gynecology | 57.1% acknowledged it was their responsibility to report such errors. Poor performance, insufficient information, slips, and lapses. | All healthcare practitioners should undergo mandatory drug safety training, and error-detecting alarms and software should be utilized. | Strengthening error reporting with robust regulations and adequate training for healthcare personnel. | Recall bias of participants, social desirability bias and communication barriers between investigators and participants may have yielded imprecise data. The study was conducted at one tertiary care center; therefore, the study results cannot be generalized to the whole healthcare population. |

| Alshahrani et al. (2019) Retrospective Observational Study [46] | 386 adult patients records were reviewed (>15 years old). Tertiary hospital. | Healthcare professional. | A total of 113 medication errors were recorded, comprising 112 prescribing errors and 1 dispensing error. Medication duplication (31.2%) was the most frequent issue, followed by missing patient-identifying information (25%). | Implementing educational interventions, such as workshops and continuous medical education, is crucial for minimizing and preventing medication errors. | Numerous medication errors have been identified with most being related to inpatient prescriptions. | This retrospective study was conducted at a single healthcare facility in the southern province of Saudi Arabia, limiting the generalizability of the results. |

| AlAzmi et al. (2019) Retrospective Observational Study [47] | 657 pediatric patients: 387 males (58.9%). Hospitalised children at KAMC-J. | Pediatric wards and/or the emergency department. 15 minor (4.6%), 312 moderate (95.1%), and 1 severe (0.3%). | 328 confirmed drug-related problems (DRPs): dosing problems accounted for 64.9% (n = 213/328) and drug choice problems for 32.9% (n = 108/328). | Incorporating a more pediatric-specific information into CPOE is essential to further reduce these problems and enhance the care. | The computerized physician order entry (CPOE) system has significantly reduced DRP incidence in children. | This study reflects the experience of a single institution. It also did not assess the outcomes of preventable DRPs or off-label medication use in pediatrics, areas that should be explored in future research. |

| Alhawassi et al. (2019) Retrospective Observational Study [48] | Review of medical records of 4073 older adults (56.8% female, 43.2% male) in ambulatory care clinics at a tertiary hospital. | Ambulatory care clinics. 57.6% of older adults had potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) to be avoided, and 37.5% had PIMs that should be used with caution. | The most frequently prescribed PIMs were gastrointestinal agents (35.6%) and endocrine agents (34.3%). | Regular medication therapy management and continuous reviews can help reduce PIM usage. | Elderly patients may benefit from a multidisciplinary care model with pharmacist follow-up to assess and minimize inappropriate medications. | The findings of this study cannot be generalized to all older adults in Saudi Arabia, as it only included older patients from the ambulatory care clinics of a single tertiary hospital. |

| Alanazi et al. (2024) Retrospective Observational Study [49] | Review of PIMs in two hospitals involving 237 patients (50.8% male, 49.2% female). | Medical/surgical wards. The overall prevalence of PIMs was 29.2%, with 11% specifically to be avoided in elderly patients. | The most common PIM medications were proton pump inhibitors (44.41%), particularly among patients discharged from the surgical unit. | Prescription monitoring is recommended to prevent medication errors, particularly for patients on multiple medications. | Community-based studies are needed to confirm this trend and identify the factors causing PIM prescriptions. | The limitations include restricted access to additional factors like socioeconomic background and prescriber details. Over-the-counter PIMs, which are common in Saudi Arabia, may have led to an underestimation of PIM frequency among the elderly. |

| Sultan et al. (2023) Retrospective Observational Study [50] | Review of direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) utilizations in a tertiary hospital with 778 patients. | Among 232 patients (29.8%), 41.7% had inappropriate maintenance doses, 37.97% had inappropriate initial doses, and 36.42% lacked laboratory monitoring. | 40.8% received rivaroxaban, 31.02% received apixaban. | They recommended establishing and monitoring an anticoagulation stewardship initiative to improve medicines utilization. | The outcomes of these suggestions have yet to be determined. | A significant percentage of patients on DOACs were excluded due to incomplete data. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tobaiqy, M.; MacLure, K. Medication Errors in Saudi Arabian Hospital Settings: A Systematic Review. Medicina 2024, 60, 1411. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60091411

Tobaiqy M, MacLure K. Medication Errors in Saudi Arabian Hospital Settings: A Systematic Review. Medicina. 2024; 60(9):1411. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60091411

Chicago/Turabian StyleTobaiqy, Mansour, and Katie MacLure. 2024. "Medication Errors in Saudi Arabian Hospital Settings: A Systematic Review" Medicina 60, no. 9: 1411. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60091411

APA StyleTobaiqy, M., & MacLure, K. (2024). Medication Errors in Saudi Arabian Hospital Settings: A Systematic Review. Medicina, 60(9), 1411. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60091411