Improved Masticatory Performance in the Partially Edentulous Rehabilitated with Conventional Dental Prostheses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Procedures

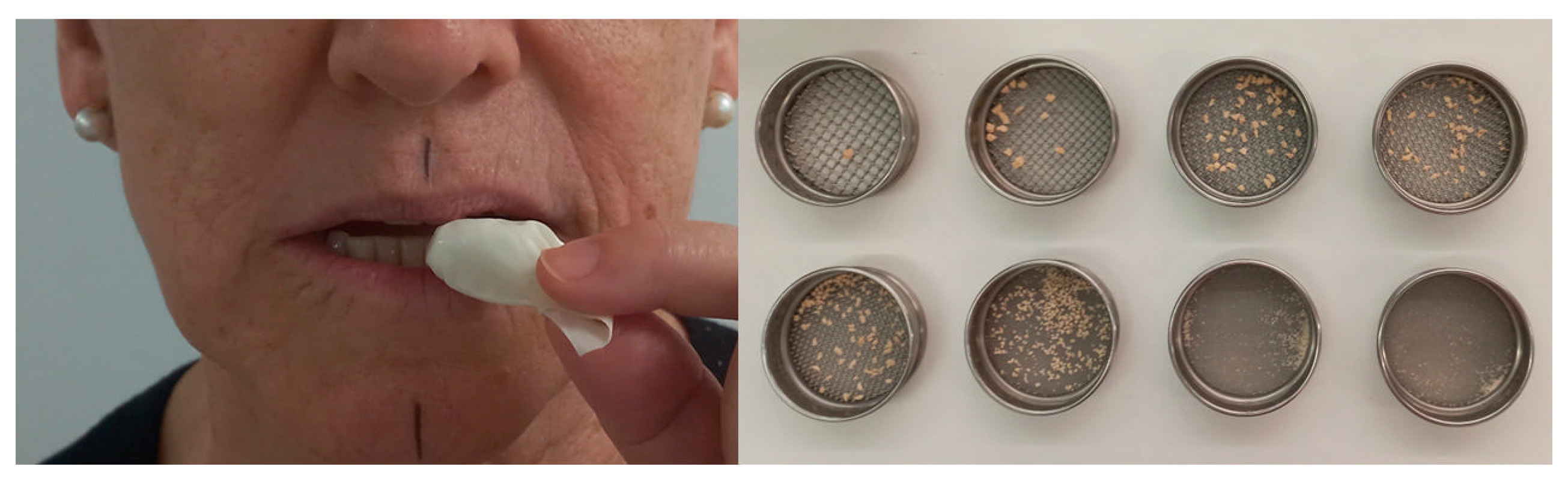

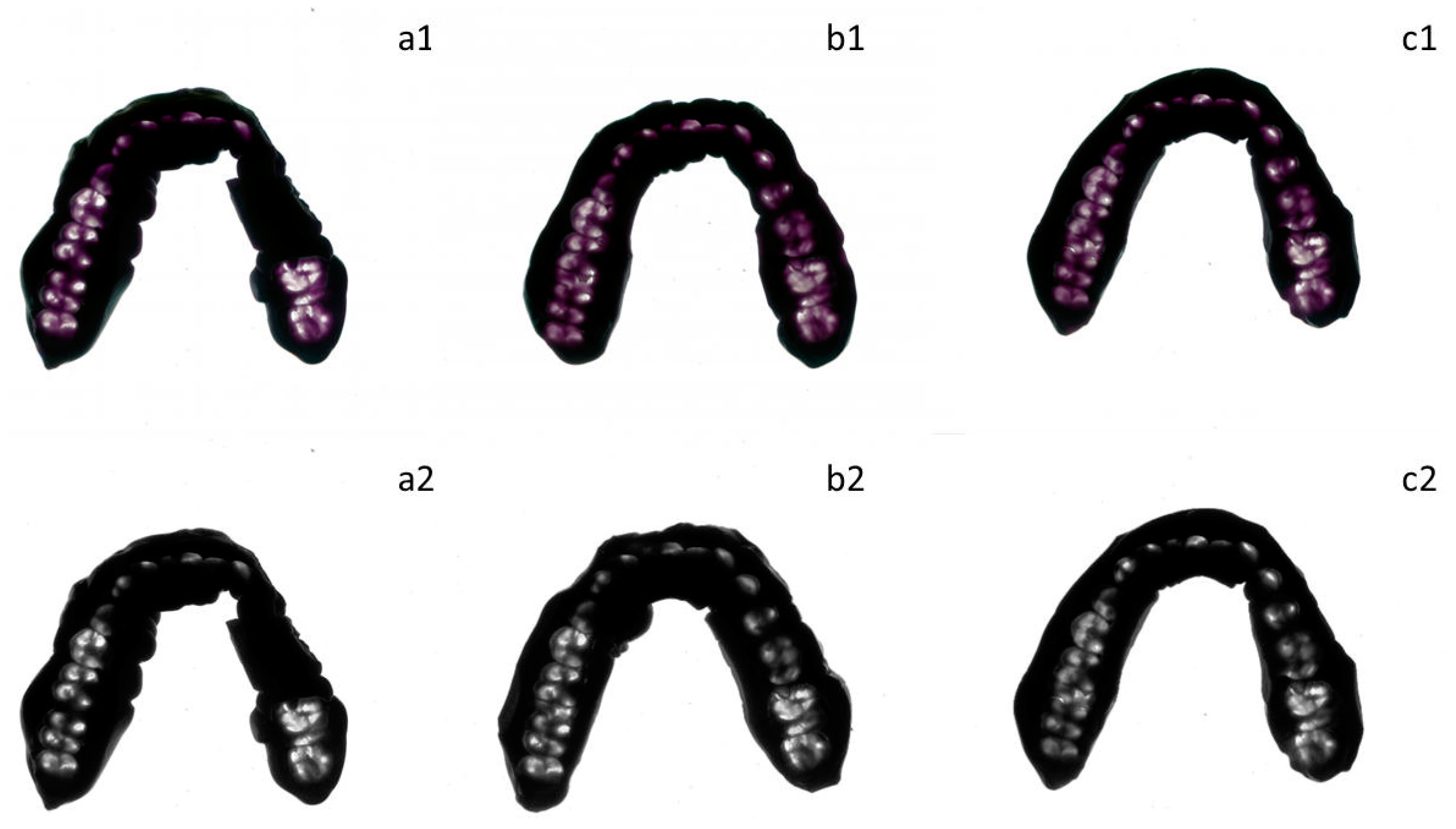

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Sample Size Calculation

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

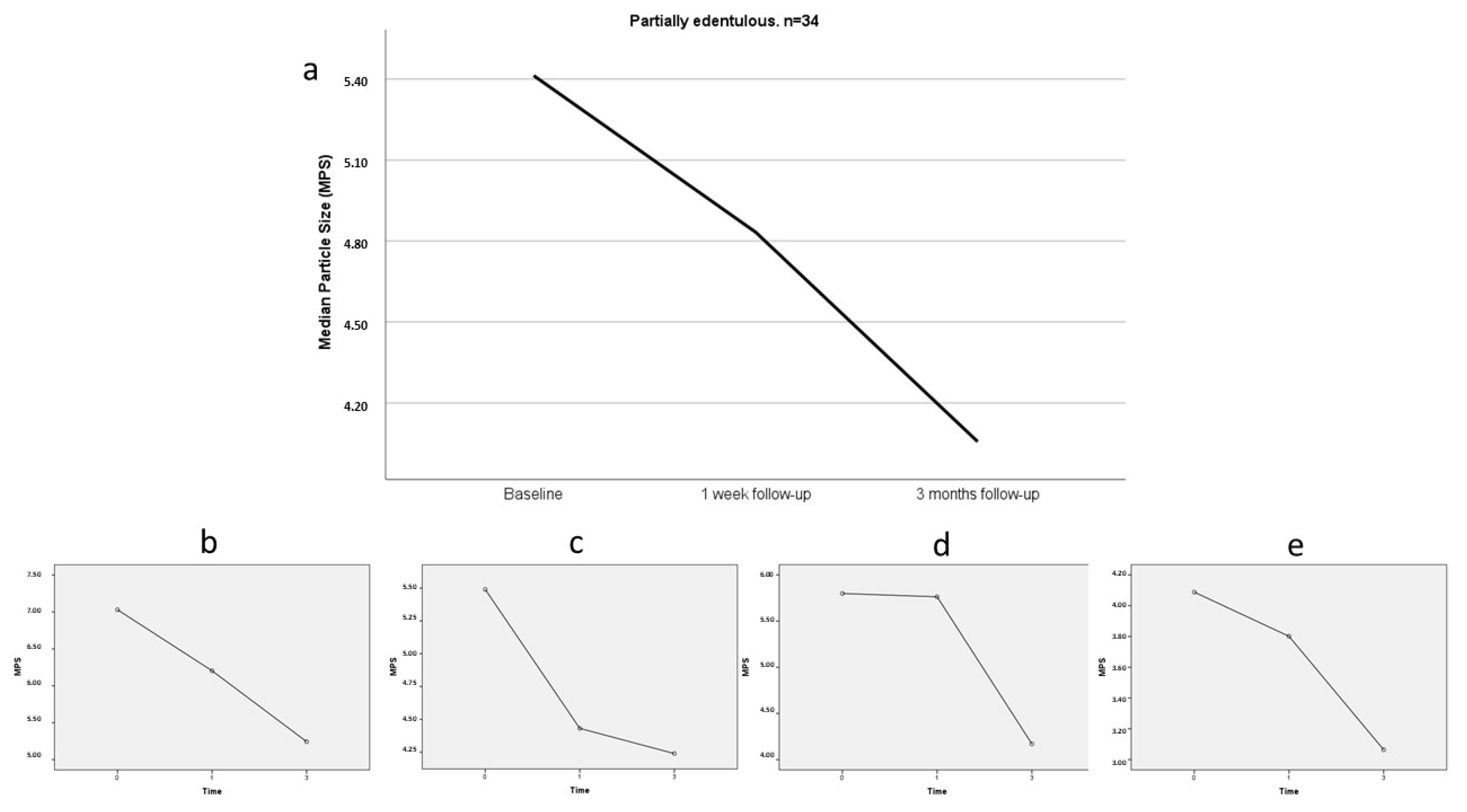

3.1. Masticatory Performance

3.2. Occlusal Contact Area

3.3. Patient Satisfaction

3.4. Factors Related to the Improvement in Masticatory Performance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tamada, Y.; Takeuchi, K.; Kusama, T.; Saito, M.; Ohira, T.; Shirai, K.; Yamaguchi, C.; Kondo, K.; Aida, J.; Osaka, K. Reduced number of teeth with and without dental prostheses and low frequency of laughter in older adults: Mediation by poor oral function. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2024, 68, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassebaum, N.J.; Bernabé, E.; Dahiya, M.; Bhandari, B.; Murray, C.J.; Marcenes, W. Global burden of severe tooth loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 93, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen, A.E.; Allen, P.F.; Witter, D.J.; Bronkhorst, E.M.; Creugers, N.H. Tooth loss and oral health-related quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaramakrishnan, G.; Sridharan, K. Comparison of implant supported mandibular overdentures and conventional dentures on quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Aust. Dent. J. 2016, 61, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissler, C.A.; Bates, J.F. The nutritional effects of tooth loss. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1984, 39, 478–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mameno, T.; Tsujioka, Y.; Fukutake, M.; Murotani, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Hatta, K.; Gondo, Y.; Kamide, K.; Ishizaki, T.; Masui, Y.; et al. Relationship between the number of teeth, occlusal force, occlusal contact area, and dietary hardness in older Japanese adults: The SONIC study. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2024, 68, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, K.; Fujita, Y.; Ohno, Y.; Takeshima, T.; Maki, K. The factors related to decreases in masticatory performance and masticatory function until swallowing using gummy jelly in subjects aged 20–79 years. J. Oral Rehabil. 2020, 47, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, K.; Hatta, K.; Mameno, T.; Takahashi, T.; Gondo, Y.; Kamide, K.; Masui, Y.; Ishizaki, T.; Arai, Y.; Kabayama, M.; et al. The relationship between changes in occlusal support and masticatory performance using 6-year longitudinal data from the SONIC study. J Dent. 2023, 139, 104763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.L. Systems for classifying partially dentulous arches. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1970, 24, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jokstad, A.; Orstavik, J.; Ramstad, T. A definition of prosthetic dentistry. Int. J. Prosthodont. 1998, 11, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zitzmann, N.U.; Hagmann, E.; Weiger, R. What is the prevalence of various types of prosthetic dental restorations in Europe? Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2007, 18, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boven, G.C.; Raghoebar, G.M.; Vissink, A.; Meijer, H.J. Improving masticatory performance, bite force, nutritional state and patient’s satisfaction with implant overdentures: A systematic review of the literature. J. Oral Rehabil. 2015, 42, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroll, P.; Hou, L.; Radaideh, H.; Sharifi, N.; Han, P.P.; Mulligan, R.; Enciso, R. Oral health-related outcomes in edentulous patients treated with mandibular implant-retained dentures versus complete dentures: Systematic review with Meta-analyses. J. Oral Implantol. 2018, 44, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, F.; Hernandez, M.; Grütter, L.; Aracil-Kessler, L.; Weingart, D.; Schimmel, M. Masseter muscle thickness, chewing efficiency and bite force in edentulous patients with fixed and removable implant-supported prostheses: A cross-sectional multicenter study. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2012, 23, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury-Ribas, L.; Ayuso-Montero, R.; Willaert, E.; Peraire, M.; Martinez-Gomis, J. Do implant-supported fixed partial prostheses improve masticatory performance in patients with unilateral posterior missing teeth? Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2019, 30, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Bilt, A.; Olthoff, L.W.; Bosman, F.; Oosterhaven, S.P. Chewing performance before and after rehabilitation of post-canine teeth in man. J. Dent. Res. 1994, 73, 1677–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Kanazawa, M.; Sato, D.; Uehara, Y.; Miyayasu, A.; Iwaki, M.; Komagamine, Y.; Naing, S.T.; Katheng, A.; Kusumoto, Y.; et al. Oral function of implant-assisted removable partial dentures with magnetic attachments using short implants: A prospective study. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2022, 33, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, S.; Samietz, S.; Abbas, M.; McKenna, G.; Woodside, J.V.; Schimmel, M. Impact of prosthodontic rehabilitation on the masticatory performance of partially dentate older patients: Can it predict nutritional state? Results from a RCT. J. Dent. 2018, 68, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, B.A.; Weatherspoon, D.J.; Lopez Mitnik, G. Tooth loss among older adults according to poverty status in the United States from 1999 through 2004 and 2009 through 2014. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2019, 150, 9–23.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomares, T.; Montero, J.; Rosel, E.M.; Del-Castillo, R.; Rosales, J.I. Oral health-related quality of life and masticatory function after conventional prosthetic treatment: A cohort follow-up study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2018, 119, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschang, P.H.; Throckmorton, G.S.; Travers, K.H.; Johnson, G. The effects of bolus size and chewing rate on masticatory performance with artificial test foods. J. Oral Rehabil. 1997, 24, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lujan-Climent, M.; Martinez-Gomis, J.; Palau, S.; Ayuso-Montero, R.; Salsench, J.; Peraire, M. Influence of static and dynamic occlusal characteristics and muscle force on masticatory performance in dentate adults. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2008, 116, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovira-Lastra, B.; Flores-Orozco, E.I.; Salsench, J.; Peraire, M.; Martinez-Gomis, J. Is the side with the best masticatory performance selected for chewing? Arch. Oral Biol. 2014, 59, 1316–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoury-Ribas, L.; Ayuso-Montero, R.; Rovira-Lastra, B.; Peraire, M.; Martinez-Gomis, J. Reliability of a new test food to assess masticatory function. Arch. Oral Biol. 2018, 87, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riera-Punet, N.; Martinez-Gomis, J.; Zamora-Olave, C.; Willaert, E.; Peraire, M. Satisfaction of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with an oral appliance for managing oral self-biting injuries and alterations in their masticatory system: A case-series study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2019, 121, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, K.C.; Buschang, P.H.; Throckmorton, G.S.; Dechow, P.C. Normal masticatory performance in young adults and children. Arch. Oral Biol. 1996, 41, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Orozco, E.I.; Rovira-Lastra, B.; Willaert, E.; Peraire, M.; Martinez-Gomis, J. Relationship between jaw movement and masticatory performance in adults with natural dentition. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2016, 74, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ayala, A.; Campanha, N.H.; Garcia, R.C. Relationship between body fat and masticatory function. J. Prosthodont. 2013, 22, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, T.E.; Buschang, P.H.; Throckmorton, G.S. Masticatory performance: A protocol for standardized production of an artificial test food. J. Oral Rehabil. 2003, 30, 720–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olthoff, L.W.; van der Bilt, A.; Bosman, F.; Kleizen, H.H. Distribution of particle sizes in food comminuted by human mastication. Arch. Oral Biol. 1984, 29, 899–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Gomis, J.; Lujan-Climent, M.; Palau, S.; Bizar, J.; Salsench, J.; Peraire, M. Relationship between chewing side preference and handedness and lateral asymmetry of peripheral factors. Arch. Oral Biol. 2009, 54, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayuso-Montero, R.; Mariano-Hernandez, Y.; Khoury-Ribas, L.; Rovira-Lastra, B.; Willaert, E.; Martinez-Gomis, J. Reliability and Validity of T-scan and 3D Intraoral Scanning for Measuring the Occlusal Contact Area. J. Prosthodont. 2020, 29, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieto-Barrio, P.; Khoury-Ribas, L.; Rovira-Lastra, B.; Ayuso-Montero, R.; Martinez-Gomis, J. Variation in Dental Occlusal Schemes Two Years After Placement of Single-Implant Posterior Crowns: A Preliminary Study. J. Oral Implantol. 2022, 48, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feine, J.S.; Maskawi, K.; de Grandmont, P.; Donohue, W.B.; Tanguay, R.; Lund, J.P. Within-subject comparisons of implant-supported mandibular prostheses: Evaluation of masticatory function. J. Dent. Res. 1994, 73, 1646–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Lund, J.P.; Taché, R.; Clokie, C.M.; Feine, J.S. A within-subject comparison of mandibular long-bar and hybrid implant-supported prostheses: Psychometric evaluation and patient preference. J. Dent. Res. 1997, 76, 1675–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, B.; Shao, L.; Yu, Q. Effect of different occlusal forces on the accuracy of interocclusal records of loose teeth. J. Oral Rehabil. 2023, 50, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.M.; Lee, S.S.; Kwon, H.K.; Kim, B.I. Short-term improvement of masticatory function after implant restoration. J. Periodontal Implant Sci. 2015, 45, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatova-Mishutina, T.; Khoury-Ribas, L.; Flores-Orozco, E.I.; Rovira-Lastra, B.; Martinez-Gomis, J. Influence of masticatory side switch frequency on masticatory mixing ability and sensory perception in adults with healthy dentitions: A randomized crossover trial. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 131, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | n | Age | No. Absent Teeth | No. Teeth Restored |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partially edentulous | 34 | 65.3 (11.1) | 5.2 (4) | 4.2 (2.3) |

| Kennedy class I | 6 | 65.6 (8.6) | 8.5 (6.9) | 6.2 (1.7) |

| Kennedy class II | 11 | 65.3 (11.7) | 5.4 (1.9) | 5.4 (1.4) |

| Kennedy class III | 17 | 65.2 (12) | 3.9 (3.3) | 2.6 (1.9) |

| Group | MPS (mm) | % MPS Reduction at 3 Months (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Baseline | 1 Week FU | 3 Month FU | ||

| Partially edentulous | 34 | 5.41 (2.3) | 4.83 (2.1) | 4.06 (1.6) ab (p < 0.001) | 20.1% (12.22 to 28.03) |

| Kennedy class I (RPD) | 6 | 7.03 (1.1) | 6.20 (1.82) | 5.24 (1.1) a (p = 0.028) | 25.1% (11.41 to 38.70) |

| Kennedy class II (RPD) | 11 | 5.49 (2.52) | 4.43 (1.83) | 4.24 (1.98) | 16.8% (−3.04 to 36.61) |

| Kennedy class III (RPD) | 7 | 5.8 (2.41) | 5.76 (2.45) | 4.17 (1.32) | 22.6% (−0.02 to 45.17) |

| Kennedy class III (FPDP) | 10 | 4.09 (0.63) | 3.8 (0.5) | 3.06 (0.26) | 19.1% (5.05 to 33.23) |

| Group | n | Baseline | 1-Week FU | 3-Month FU |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partially edentulous | 34 | 12.14 (7.48) | 12.69 (6.7) | 16.82 (7.8) ab (p < 0.001) |

| Kennedy class I (RPD) | 6 | 12.71 (5.72) | 6.78 (3.39) | 11.77 (4.68) |

| Kennedy class II (RPD) | 11 | 11.19 (7.36) | 12.05 (6.74) | 15.45 (8.3) a (p = 0.038) |

| Kennedy class III (RPD) | 7 | 11.23 (5.83) | 12.26 (5.26) | 15.58 (4.56) a (p = 0.018) |

| Kennedy class III (FPDP) | 10 | 13.70 (10.14) | 16.48 (7.38) | 20.96 (8.94) a (p = 0.002) |

| Group | n | 1 Week FU | 3 Month FU |

|---|---|---|---|

| Partially edentulous | 34 | 8 (2.28) | 8.91 (1.81) * (p = 0.006) |

| Kennedy class I (RPD) | 6 | 8.04 (2.98) | 7.88 (1.86) |

| Kennedy class II (RPD) | 11 | 7.71 (2.02) | 8.68 (2) |

| Kennedy class III (RPD) | 7 | 6.44 (2.16) | 8.34 (1.61) * (p = 0.018) |

| Kennedy class III (FPDP) | 10 | 9.26 (1.79) | 9.99 (1.42) |

| Group | n | MPS Reduction | OCA Variation | Satisfaction Variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partially edentulous | 34 | 1.36 (1.5) | 4.68 (7.2) | 0.92 (1.9) |

| Kennedy class I (RPD) | 6 | 1.79 (1) | −0.94 (7) | −0.16 (2.3) |

| Kennedy class II (RPD) | 11 | 1.25 (1.7) | 4.26 (6.8) | 0.97 (1.7) |

| Kennedy class III (RPD) | 7 | 1.63 (1.7) | 4.35 (5.3) | 1.9 (1.8) |

| Kennedy class III (FPDP) | 10 | 1.02 (1.4) | 7.25 (8.8) | 0.73 (2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lopez-Cordon, M.A.; Khoury-Ribas, L.; Rovira-Lastra, B.; Ayuso-Montero, R.; Martinez-Gomis, J. Improved Masticatory Performance in the Partially Edentulous Rehabilitated with Conventional Dental Prostheses. Medicina 2024, 60, 1790. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60111790

Lopez-Cordon MA, Khoury-Ribas L, Rovira-Lastra B, Ayuso-Montero R, Martinez-Gomis J. Improved Masticatory Performance in the Partially Edentulous Rehabilitated with Conventional Dental Prostheses. Medicina. 2024; 60(11):1790. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60111790

Chicago/Turabian StyleLopez-Cordon, Maria Angeles, Laura Khoury-Ribas, Bernat Rovira-Lastra, Raul Ayuso-Montero, and Jordi Martinez-Gomis. 2024. "Improved Masticatory Performance in the Partially Edentulous Rehabilitated with Conventional Dental Prostheses" Medicina 60, no. 11: 1790. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60111790

APA StyleLopez-Cordon, M. A., Khoury-Ribas, L., Rovira-Lastra, B., Ayuso-Montero, R., & Martinez-Gomis, J. (2024). Improved Masticatory Performance in the Partially Edentulous Rehabilitated with Conventional Dental Prostheses. Medicina, 60(11), 1790. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60111790